Emergency personnel are exposed to particularly high levels of physical and psychological stress, entailing occupational risk of mental illness. Reference Vandentorren, Pirard and Sanna1 Because of this risk, sampling procedures are in place at certain organizations to determine the resilience of personnel to occupational stressors. In recent years, topics such as mental fitness, healthy sleep, and well-being of workers have come into focus. Reference Bajo, Blanco and Stavraki2 Forms of preventive preparation and follow-up procedures for specific target groups have been developed.

Some studies have identified occupation-specific as well as gender-specific changes after a high-stress rescue operation, Reference Birkeland, Blix and Solberg3,Reference Brooks, Dunn and Amlôt4 which has led to the recommendation of gender-specific preparation and follow-up procedures. Observed differential changes should be considered and incorporated into preventive measures to establish health-related equality in initial and continuing training. Reference Wesemann, Zimmermann and Mahnke5

To meet the needs of different gender groups, a systematic assessment of gender-specific effects after extreme events is necessary. Non-cisgender identities are no exception within emergency or military personnel; in the US military, the rate of transgender adults is 2 to 3 times higher than in the comparable civilian population. Reference Tucker6 In Germany, a third gender, “diverse,” (non-binary; German: divers) was only established as an official gender in 2019, so statistics are not yet available for German forces. However, due to special medical coverage, such as the absorption of costs for sex reassignment, and protection against dismissal or discrimination, the proportion of transgender employees is likely to be higher among state and federal institutions than civilian employers.

International studies have observed reluctance to use existing health-care services among this population. This reluctance seems to especially affect mental health. Poor mental health has been seen in non-cisgender US military veterans, compared with cisgender male and female veterans, and the suicide rate among transgender veterans is double that among the general population of veterans. Reference Tucker6

Despite poorer mental health in this population, there are still no studies on outcomes of transgender individuals after a potentially traumatizing incident. The rate of harassment, trauma, and sexual assault is higher among transgender and gender queer participants in the database of Center for Collegiate Mental Health Database 2012–2016 than among cisgender men or women. Approximately 50% of the 892 genderqueer participants reported all 3 of these experiences. Reference Tyler Lefevor, Boyd-Rogers and Sprague7 In contrast, a study in Brazil did not find that being transgender was a risk factor for increased stress. Rather, rejection by society and friends, present in 90% of cases, seemed to lead to increased psychological stress. Reference Lobato, Soll and Costa8

In summary, psychological stress and symptoms of mental illness are generally higher in non-cisgender populations than cisgender populations. In particular, rejection from society and exclusion seem to play a decisive role in the development of psychological symptoms. Furthermore, it has been shown that the integration of this population into existing health-care systems is deficient in multiple countries. Reference Beckwith, McDowell and Reisner9 Thus, a future goal is to establish health-related equality in this regard.

An exploratory pilot study on the effects of the terror attack at Breitscheidplatz in Berlin revealed indications of gender differences among first-responding emergency personnel. Reference Wesemann, Zimmermann and Mahnke5 In a subsequent confirmative study, the findings of increased stress and paranoid ideation among female personnel could be replicated. Reference Wesemann, Mahnke and Polk10 The results were attributed to more frequent sexual assaults against women in male-dominated professions, which could increase vulnerability. Sexual harassment and sexual assault are found to be higher in the transgender population, as well. Reference Tyler Lefevor, Boyd-Rogers and Sprague7 It is, therefore, assumed that the differences prevail here as well.

The objective of this single-case-versus-group comparison is to investigate whether gender-specific differences in stress and paranoid ideation following a terror attack are also present in a transgender male emergency worker.

Methods

All firefighters, police, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and civil and military rescue workers deployed to the terror attack at Breitscheidplatz in Berlin had the opportunity to participate in the study. The recruitment was conducted with the consent of the organizations. Task force leaders were informed about the study and invited to participate. If task force leaders agreed, brief information sessions were held for the respective units, and attendees were informed about the purpose of the study. Inclusion in the study was voluntary and written informed consent was obtained from all who participated. The first survey took place 3 to 4 mo after the attack (December 19, 2016), and the second survey was distributed by mail 18 to 21 mo later. A total of 60 emergency personnel participated at the first time point: 42 cisgender male, 17 cisgender female, and 1 transgender male (assigned female at birth, the sex change operation took place more than 10 y ago). The response rate at the second time point was 65% (n = 39), and the transgender male worker responded at both time points. The gender identity of the participant was confirmed in a personal interview, and a written declaration of consent for this publication was obtained.

The study consisted of a questionnaire packet with a demographic section and the following measurement instruments:

Stress was assessed using the stress module of the Patient Health Questionnaire in German [PHQ-D]. This is a psychodiagnostic questionnaire that measures psychosocial stress factors using 10 questions. The stress factors can be seen as triggers or maintenance factors for mental disorders. Possible answers are 0 = not impaired, 1 = somewhat impaired, and 2 = severely impaired.

Current mental state was evaluated with the Brief Symptom Inventory [BSI], which consists of 53 items surveying symptoms of psychiatric disorders. The subscales measure the areas of somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism.

Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS (Version 21, IBM Inc., Armonk, NY). Missing values at the second time point were imputed using the first/last observation carried forward method. Due to the individual case analysis, it was not possible to use inferential statistical methods; thus, a purely descriptive evaluation was carried out. Here, the raw scores of the transgender male rescue worker were compared with the mean values of the cisgender male and female groups, taking the standard deviations (SDs) into account. A result is considered conspicuous if it falls 1 SD above or below the mean value of at least 1 other gender group and the overall group.

Results

The transgender male rescue worker showed comparable scores in stress (PHQ) to both cisgender groups at both time points.

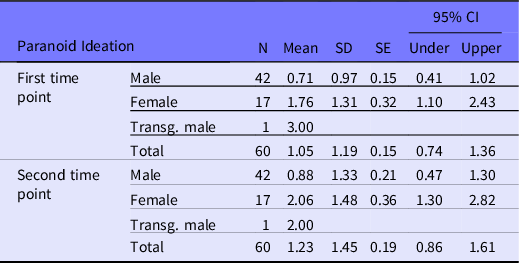

At the first time point, there were no adverse effects on aggressiveness or hostility in the transgender male worker, and his scores fell 1 SD below that of cisgender male group, as well as that of the overall group. This difference was no longer present after 2 y. The transgender male worker showed increased paranoid ideation at the first time point (2 SDs above cisgender males and 1 SD above the overall group), which normalized by the second time point as shown in Table 1. He also reported interpersonal sensitivity scores 1 SD above cisgender males and the overall group. All other scores were inconspicuous.

Table 1. Increased paranoid ideation in the transgender man and cisgender women

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error; Transg., transgender.

Conclusions

The transgender male rescue worker showed comparable scores to the group on most scales, which highlights an underlying resilience required of emergency personnel in general. The influence of gender on paranoid ideation after the terror attack was also seen descriptively in the transgender male worker. The fact that specifically this hypothesis-targeted scale showed greater adverse effects at the first time point indicates a valid result, despite the individual case-by-group comparison. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that exposure to extreme events weakens trust generally. Reference Brooks, Dunn and Amlôt4 However, that there is a disadvantageous differential effect on transgender male and cisgender female emergency personnel cannot currently be derived from this theory. A higher susceptibility to mistrust in transgender individuals and cisgender females due to past harassment or assault in a cisgender male-dominated profession could have a mediating effect here. Furthermore, this underrepresentation of cisgender women or transgender individuals may help explain gender stereotyping and harassment in the workplace, according to theories of tokenism. Increased interpersonal sensitivity may be a long-term outcome following earlier aggression inhibition and increased paranoid ideation.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate psychological stress associated with a terror attack in transgender males, and the results should be considered as preliminary to further research. Additionally, the study is limited by current subsamples, which are overall small and consist of different occupational groups of emergency personnel. Due to a drop-out rate of 39%, missing data points were imputed at the second time point, which notably restricts interpretation of the effects seen after 2 y.

A continuing objective is to systematically survey specific stress factors for different occupational groups and genders, and to compare these with stress burdens caused by natural disasters or accidents. In the long term, specific prevention, intervention, and health-promoting measures should be developed and implemented, guided by these results. This could promote health-related gender equality and be put to use in anti-stigmatization programs. In crisis interventions in particular, gender differences between cisgender male and female emergency personnel still seem to lead to inequalities in outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Charlyn Löpke and Sandra Wetzel for their smooth organization, both from the Bundeswehr Hospital Berlin.

Funding

No competing financial interests exist.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Charité (part of the Humboldt University Berlin).