Introduction

Baruch Agadati (1895–1976), the Israeli choreographer, filmmaker, and painter never came out of the closet. The homosexuality of “the first bohemian in modern Israel” (Manor Reference Manor and Gerstner2006), whose work spanned from the late Ottoman Empire to the early 1970s, remained a topic of speculation and a more or less open secret. Only recently has Agadati been officially outed by Yitzhak Laor, one of Israel's leading intellectuals, who in a Haaretz review of Liora Bing-Heidecker's book on dance and Zionism (Bing-Heidecker Reference Bing-Heidecker2016), described Agadati as a “homo ḥalutsi” (Laor Reference Laor2017). This Hebrew expression translates best to “a pioneering gay man” and refers to Agadati's pathbreaking role as a homosexual artist in Israeli culture. Though by no means an early gay activist, he was the first protagonist of modern dance in Israel who found ways to bring his sexuality onto the stage. More than this, based on his own marginalized position as a homosexual Jewish dancer, Agadati queered Jewish dance and transcended boundaries of religion, secularity, and nation to a multidimensional questioning of how Jewishness could be expressed through dance. The sensibility for the specifically queer character of his approach to movement and choreography is new and adds an important and necessary twist to Agadati's reputation as “the pioneer of modern dance in Israel” (Manor Reference Manor1986), as he has long been regarded (Malka-Yellin Reference Malka-Yellin2007, 41–56; Aldor Reference Aldor and Ingber2011, 378; Eshel Reference Eshel and Ingber2021, 12–15; Spiegel Reference Spiegel, Jackson, Pappas and Shapiro-Phim2022, 153–154).

In the following article, I argue that Agadati queered Jewish dance in a twofold way: First, being homosexual, even if in the closet or especially because of it, made Agadati's artistic projects queer. Second, aside from his sexual orientation or the speculations around it, the scope and style of his interventions also contributed to his queer dance. Queering is here understood as the aesthetic practice of subverting normativity and questioning essentialist categories carried out by a nonheterosexual artist. This queering through dance “refuses monolithic signification and instead forges a politics from the productive frictions among identities” (Croft Reference Croft2017, 2–3). In coupling both notions of queer, the personal nonheterosexual identity and the nonnormative aesthetic practice, this underlying definition of queering avoids equating any subversion of normativity through movement with queer dance. Such radical extension, regardless of “the sexual preferences of the dancers or choreographers,” not only “carries the danger of losing the scope, the impetus, and the direction of its ethical and aesthetic commitment” (Schwan Reference Schwan2019a, 123) but also misses the biographical situation of Agadati and many other homosexual modernist artists in whose dance work both aspects of queer converged.

Because of his sexual orientation, Agadati was forcedly sensibilized for the exclusion mechanisms of mainstream culture, in this context the traditionally heterosexual setting of dance in Eastern European Judaism (Gollance Reference Gollance2021), the background from which he himself stemmed or the Chassidic Judaism from which he drew inspiration for his own work. In Chassidim, for example, heteronormativity is at work in the strong tie of dancing to heterosexual weddings and the religious duty of a Mitzwah tantz, a male dance performed in front of the bride (Ingber Reference Ingber and Ingber2011, 6). However, Agadati was also aware of the various homoerotic aspects within the traditional link of Jewishness and dance when, for example, the separation of sexes in dancing provides a setting for men dancing with men, or when male dancing can be charged with religious meaning regardless of heterosexual love and reproduction (Talabardon Reference Talabardon and Walz2022).

Seeing both the heteronormativity of Jewish dance and the questioning of the same already at work within the tradition, Agadati approached Jewish dance from a side perspective and with aesthetic principles in line with deliberately queer aesthetics. He distorted established understandings of Jewish spirituality and dance, and deconstructed apparently essentialist categories like male and female dancing. Furthermore, his queer dance aesthetics also included a deliberate avoidance of virtuosity, perfection, and flawlessness, and embraced a “queer art of failure” (Halberstam Reference Halberstam2011) in appreciating amateurish, awkward, and disruptive moments that undermined otherwise heteronormative ideals of wholeness and completeness.

In his dance works and in the publications around them, Agadati replaced these essential ideals with exposed artificiality and constructedness. As in the case of many other modernist choreographers, like Harald Kreutzberg, Yvonne Georgi (Lim Reference Lim2022), and earlier and most notoriously Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn (Shawn Reference Shawn1920), his queering of Jewish dancing included various forms of Orientalism (see also Garber Reference Garber1992, 304–352). With these, he exoticized representatives of Judaism as well as Palestinian Arabs, or drew on non-Jewish pictorial traditions of the Middle East. A bizarre example is the photomontage “Persian Motif,” which portrayed him hovering on a background of ornamental patterns, his body wrapped in an extravagant silk robe, his head surrounded by an aureole-like shape: Agadati, the proud, self-proclaimed prophet of modern dance (Agadati Reference Agadati1925, n.p.).

A Queer Prophet of Modern Dance

Baruch Agadati was born Boris Kaushansky in 1885 in Bessarabia in the Russian Empire; from there he immigrated to Jerusalem as an unaccompanied fifteen-year-old teenager in 1910. His career as a dancer began three years later and started with a scandal. We are in the year 1913: not in Paris, not at the première of The Rite of Spring, but in Jerusalem, at the recently established Bezalel art academy, where Baruch Agadati, then named Baruch Ben Yehuda, was enrolled as a student of fine arts (Katz Reference Katz and Agadati1927). On the invitation of the headmaster of Bezalel, Abel Pan, Agadati performed a dance improvisation to one of Liszt's Mephisto waltzes. In the audience: Hemda Ben Yehuda, the wife of Eliezer Ben Yehuda, the Hebrew lexicographer and newspaper editor whose project was to revive the Hebrew language in the modern era (Manor Reference Manor1986, 7–8).

I am quoting from a description of the performance by Isaac Katz from 1927, published in French in a small booklet that celebrated Agadati's career as a dancer. For the Mephisto waltz, Agadati (in my own translation of the French text) “donned a black coat as his only attire and, during the performance, right in front of the audience, in a beautiful turn of the waltz, in the moment when one side of his coat had been very indecently raised, he appeared naked, completely naked, in the full height of his then emaciated and puny body, naked as on the bright day on which his holy and good mother brought him forth into the world” (Katz Reference Katz and Agadati1927, n.p.).

Oscillating between unintended exposure and willful provocation, Agadati's nudity was more than just daring. In denuding his own extremely slim physique as a young homosexual man—the French original describes his body as “corps étique et malingre” (Katz Reference Katz and Agadati1927)—Agadati showed a nonnormative masculinity that differed from nude bodies displayed in more heterosexual performances. Showing his own homosexual body in a performance that refused a singular reading, Agadati queered the Mephisto figure and combined a corporeal reference to his own sexuality with a subversion of the normativity of masculinity and performance of his time.

Consequently, Mrs. Ben Yehuda left the performance in the middle of the dancing, outraged by the exposed “Mephistophelian quintessence” (Katz Reference Katz and Agadati1927). She accused the then named Baruch Ben Yehuda of insulting and injuring her “honorable family name” (Manor Reference Manor1986, 8). Following this scandal, Baruch dropped the name Ben Yehuda, and one year later, and unrelated to the incident at Bezalel, he left Jerusalem under suspicious circumstances—some sources assume a family vacation in Imperial Russia, others speak of a deportation to Alexandria at the beginning of World War I. Because of the war, he had to remain in Odessa, where he enrolled in a ballet school at the age of nineteen. A few years later, despite his unusually mature age and his equally uncommon tallness of 1.90 cm, he was engaged by “the Odessa Municipal Theatre's ballet company as a soloist” (Manor Reference Manor1986, 8) in 1918. Immediately after the end of World War I, Agadati rejoined the Yishuv, the body of Jewish residents in the land of Israel prior to the establishment of the State of Israel. As part of the third aliyah (immigration wave), he embarked on the SS Ruslan in Odessa and, together with many other Jewish intellectuals and artists, among them the poet Rachel (Bluwstein Sela), he arrived in Jaffa in December 1919 to settle in Tel Aviv (Manor Reference Manor1986, 8).

Having grown up in the religious context of Eastern-European Judaism and then living a more secular lifestyle, he nonetheless remained deeply engaged with Jewish culture in Hebrew or Yiddish. Agadati shared this multilayered identity with many other Jewish artists from Eastern-Europe who similarly approached the religious context of their upbringing from a newly gained secular perspective. Here, Agadati's interest in traditional forms of Jewish dancing was characteristic of his position as a secular Jewish dancer. In Odessa, in the years before his re-immigration to the Yishuv, he had observed and studied movement material belonging to traditional Chassidic Jewish dancing in the Pale of Settlement, the Western part of Imperial Russia in which permanent residency by Jews was allowed.

Back in British Mandatory Palestine, Agadati sought to create a new style of concert dance that referred back to his ethnographic studies in Jewish communities. For this, Agadati condensed and transformed movement material from Yiddish dance to a new phenomenon that he called Hebrew Dance. He separated movements, gestures, and entire narratives and figures from Chassidic contexts, changed and twisted them, and blended this material into a new form of concert dance. Himself a nonobservant Jew, non-Orthodox and non-Chassidic, Agadati queered traditional Jewish dancing and put it in a new secular perspective.

In terms of movement practices, this meant an imitation and exaggeration of body concepts and gestural repertoire typical for Yiddish dance, like the division between the upper and the lower body or the angularity in the movement of the arms (Feldman Reference Feldman2016, 163–204; Gollance Reference Gollance2019, 112). Agadati adopted and emphasized these principles and gave his creation of Hebrew Dance an almost geometrical appearance. In his performative impersonations of Jewish figures, he also copied and intensified gestural material that could be observed in the communication of Eastern European Jews (Efron Reference Efron1972), or quoted from the positioning of fingers in the birkat kohanim (priestly blessing). With no intension of accurate imitation, this adopting, copying, and quoting of movement material rendered Hebrew Dance playful, expressive, and ornamental.

Whereas Chassidic Jewish dancing primarily happens in community—in synagogues, on festivities, but less on stages—Agadati's transformation of Chassidic movement language was created for dance performances in theater venues. This is not to be confused with a secularization or even a profanation of religious dance practices, as Chassidic dancing does not claim to be sacred and could also happen outside of religious contexts. Rather, the shift from community dancing to concert dance yielded Agadati's creation its specificity, and consequently, he named this new phenomenon ha-maḥol ha'ivri, “Hebrew Dance,” using the Hebrew word ha-maḥol, which refers primarily to dance as art. Interchangeably, Agadati also used the term ha-rikud ha'ivri, which means “Hebrew Dance” as well, but with the semantic space of ha-rikud as a reference to dancing in general (Agadati Reference Agadati1925).

Together with the shift from community dancing to concert dance, came a change in the cultural and sociological setting of the performance practice: Hebrew Dance took place in theaters and for a secular audience that, at least when performed in Mandatory Palestine, also had a Zionist background. For this new setting, Agadati supplemented the context of religious Judaism with the idea of the Hebrew, an idealization of the Jewish past that Zionism sought to revive. Agadati's Hebrew Dance is therefore best described as a queer Zionist project.

Hebrew Dance

The idea of Hebrew Dance was different from nationalist assumptions of cultural identity and an allegedly unique entity of “Jewish Dance,” which, as Agadati knew, does not exist. Instead, he realized that the movement material in traditional forms of dancing in Jewish contexts—at Simchat Torah, at weddings, and in Chassidic mysticism—was intertwined with dancing in non-Jewish contexts, from which this movement material was adopted and transformed. The best secondary source from which to get an impression of how Agadati developed his project of Hebrew Dance is the work of the Israeli dance scholar Giora Manor (1926–2004). Manor shared with Agadati the multiple identities of a homosexual Jewish immigrant from Eastern Europe whose sexual orientation and identity were only fully revealed quite recently—in the case of Manor, in 1996, when he “‘came out of the closet’ in an interview in HaDaf HaYaroq (The Green Page), the official magazine of the kibbutz movement to which he belonged” (Brom Reference Brom, Kraß, Sluhovsky and Yonay2021, 291). In his lengthy study of Agadati (Manor Reference Manor1986), Manor gives a detailed analysis of the Jewishness or non-Jewishness of the material that Agadati used for the creation of Hebrew Dance:

His research led him to the Chassidic communities in the “pale of settlement” and he came to the conclusion that what was regarded as Jewish dance and Jewish music was in reality material borrowed from the gentile environment. [The] dances became Jewish due to the changes in tempo they underwent, as well as the hand-gestures added in the course of their adoption by the Jews and the differences in posture. All these characteristics lent the gentile folk dances … an introverted spirituality and religious fervor not found in the original versions. (Manor Reference Manor1986, 8)

Agadati's reviews in Hebrew, Yiddish, and German were often sceptical about his Hebrew Dance project and quite critical of his dance technique in general, criticizing the static character of his performances and his unelaborate footwork. All the more important, then, were Agadati's strategies of self-marketing, which included advertisements in the leading newspapers of the Jishuw with which he announced his performances and touted his dance classes for the broader public, both adults and children. He published expensive, bibliophilic books about his performances, tours, and his conception of Hebrew Dance.

Paying tribute to the fact that Agadati's books were published in the British Mandatory Palestine of the 1920s, with limited technical and distributional equipment for book publishing, emphasizes their extraordinariness. This is particularly relevant for his most extravagant book, the album-formatted Baruch Agadati: The Hebrew Dance Artist, published as a limited edition of only one hundred copies in Tel Aviv in 1925, with essays by Asher Barash, Isaac Katz, and Menashe Rabinovitz, as well as thirty-two glued-in reproductions of photos of dancers, illustrations, and sketches of dancers’ figures (Agadati Reference Agadati1925). For this album, Agadati might have been inspired by similarly bibliophilic albums produced by dance artists in Europe and the United States at the same time. However, the production context of Mandatory Palestine made his book—still possible to purchase by auction or to consult in the facsimile edited by Giora Manor (Reference Manor1986)—stand out.

Beside this extravagant self-promotion, Agadati was prominently featured by Rachel Vishnitzer Bernstein in her art journal Milgroym, published in Berlin in the early 1920s. “Arguably the most visually stunning of the interwar … journals [and] part of a wave of Jewish modernist journals that viewed art as a critical aspect of the modernist enterprise,” Milgroym, which translates to “pomegranate,” “was published in Yiddish, not in support of Yiddishism or other nationalist politics, but because Yiddish was viewed as the most expedient cultural vehicle to situate Jewish culture within the Western tradition for Jewish readers” (Brenner Reference Brenner2018).

It was here, next to high-quality reproductions of Boris Aronson's costume sketches for Baruch Agadati, that Rachel Vishnitzer Bernstein described the dance art of Agadati with the unusual wording “Bewegungs-Bild” (Vishnitzer Reference Vishnitzer1923: 47). This German term in the midst of her Yiddish text translates to “movement image,” and Vishnitzer had probably chosen it as a nod to Henri Bergson's Matter and Memory (1896), unknowingly anticipating Gilles Deleuze's usage of the same word in Cinema 1: The Movement Image (Deleuze Reference Deleuze1986).

With “Bewegungs-Bild” referring not to cinema, but to dancing, Vishnitzer characterized Agadati's relationship between performance and visual art. Distancing himself from modernist concepts of continuous dance movement, as for example in the case of Isadora Duncan, Agadati stuck to the older interconnection of posing and moving, with posing as the closest approach to visual representations of human bodies. This becomes obvious in the staged photography of him, which referred back to his performances and showed him using the corporeal gestures with which he portrayed typical Jewish characters from Eastern Europe: a Chassid, a rabbi, a Talmud student.

How is Jewishness performed in Agadati's dance pieces? In a first answer, I would point out the various explicitly Jewish characters and biblical stories represented in his pieces. His early dance cycle Melaveh Malkah (also called Melave Malka or Melava Malka, meaning “escorting the queen”), refers to the religious and cultural practice of figuratively escorting the Shabbat Queen, the traditional metaphor for Shabbat in Jewish liturgy, on her way out via musical performances, singing, and dancing. The practice of escorting the Shabbat Queen takes place at the end of the Shabbat on Saturday evening.

In his performance, Agadati did not embody the Shabbat or give a drag performance of the Shabbat Queen, like contemporary queer Jewish dance artists such as Stuart Meyers do today (Meyers Reference Meyers2018). Neither did he opt for dance pieces directly visualizing the Shabbat-related theological ideas of creation, recreation, and redemption. Instead, Agadati refrained from dancing abstract Jewish theologoumena, religious concepts, or ideas, but referred to already existing cultural practices of dancing in a Jewish concept. He intensified and transformed these practices and created four Chassidic archetypes that reflected different attitudes and behaviors after the end of Shabbat: Reb Meir, Reb Netta, Reb Joel, Reb Shachna. The idea of having four archetypical rabbis is similar to the four sons from the Passover Haggadah, from where Agadati might have drawn his inspiration, yet without developing a full parallel between the four rabbis and the four sons.

In Melaveh Malka (1927; costume: Boris Aronson; music: Joel Engel and Yacob Weinberg), “there were four types of Chassidim: Reb Meir is the learned Chassid, whose parting from ‘Queen Sabbath’ is full of longing, mystical love for an ideal of spirituality; his counterpart Reb Netta a simple Jew, uneducated, a peasant at heart, who introduces earthly reality into the mystery of the holy day; the third figure is Reb Joel, the ethereal spirit of the late grandfather of Reb Meir, who comes to visit from the other world, and his opposite, the last figure of the dance-cycle, Reb Shachna, another very real, everyday Chassid” (Manor Reference Manor1986, 7).

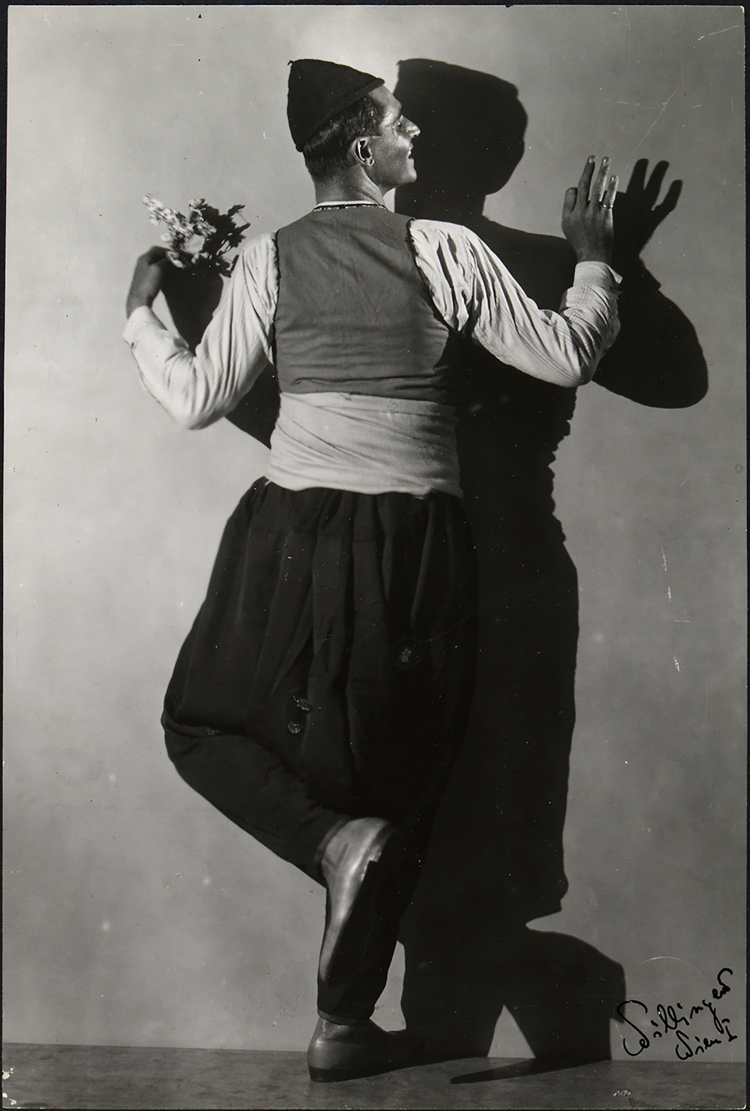

As can be seen in Photo 1, taken in the studio of Wilhelm Willinger in Vienna in 1927 and showing Agadati in his embodiment of one of the four rabbis, it was the costuming, makeup, and jewelry that rendered Melaveh Malka a decisively queer character. Although he wore traditional garments and accessories of Chassidic Jews—most significant were the various prayer shawls and hats with which he used to characterize the four Chassidim—he combined these clothing elements in a theatrical, almost carnivalesque way. The large golden ring on the little finger of his right hand and the additional draped silk shawl—or, in other appearances, the dazzling belt around his waist—were far from typical for everyday Eastern European Jews. Rather, the artificial beards and the heavy kajal makeup around Agadati's eyes put his appearance in direct parallel to the phenomenon of Chassidic drag that was widely common in performances by modernist Jewish dancers such as Else Dublon and Gertrud Kraus (Shandler Reference Shandler2006; Rossen Reference Rossen2014: 27–61). While they embodied male Orthodox Jews from their perspective as female dancers, Agadati's male-as-male drag intensified the already queer character of this cross-dressing performance practice.

Photo 1. Baruch Agadati in Melaveh Malka (1927). Photo: Atelier Willinger, Vienna, © KHM-Museumsverband, Theatermuseum Vienna.

Queering the Body Contour

In most of his Jewish-themed dance pieces, such as Melaveh Malka, Agadati performed typified Jews from Ashkenazi in Eastern European contexts. A prominent exception to this was Agadati's portrayal of Yemenite Judaism, which he approached from an Orientalist perspective. Himself not a Yemenite Jew, Agadati exoticized Yemenite Judaism by condensing and transforming movement material and gestures from Yemenite body practices (Guilat Reference Guilat2001). This was close to, yet different from, phenomena of exoticizing in the work of other modern choreographers, for example, Ted Shawn and his appropriation of Native American otherness. Whereas Shawn imitated Indigenous aesthetics from the perspective of white supremacy and in the tradition of settler colonialism, Agadati exoticized Yemenite culture as another branch of Judaism. In idealizing Yemenite otherness, he found a vehicle to express pride for his own Jewishness. He achieved this by imitating the sister branch of his own tradition, not in an ethnographical manner but in focussing on certain visual and kinesthetic aspects that he then amalgamized into a corporeal fantasy of idealized Oriental and allegedly more original Jewishness.

For this extravagant facet of Agadati's Hebrew Dance, costuming played a decisive role. Also published in Vishnitzer's Milgroym and designed by Boris Aronson, the pictorial representations of Agadati in his costume for Yemenite Ecstasy (1920) are remarkable in several ways (Milgroym 1923, 28; Rich and Aronson Reference Rich and Aronson1987, 9). They are outstanding examples of Agadati's cooperation with visual artists of his time who influenced his dance aesthetics, helped him to realize his project of queering Jewish dance, and launched this project into the visual art avant-garde. Photo 2 shows Agadati in one of Aronson's works for Yemenite Ecstasy in a montage of drawing and cutout photography.

Photo 2. Baruch Agadati, Movement Study in Expressionist Dance Costume for Yemenite Ecstasy (1920). Costume and Drawing: Boris Aronson. Photo: Atelier Willinger, Vienna, ca. 1925, © KHM-Museumsverband, Theatermuseum Vienna.

Boris Aronson, born in 1900 and the son of the chief rabbi in Kyiv (and later in Tel Aviv), had worked in the studio of Aleksandra Ekster and adopted her approach to theater costume design as a combination of Cubo-Futurist and Constructivist aesthetics. He left the Soviet Union in 1922 and, after intervals in Berlin and Paris, immigrated to the United States in late 1923. Here he would eventually become one of the most influential stage designers working on Broadway plays and musicals, including Fiddler on the Roof and Cabaret, and productions for the Metropolitan Opera such as Mikhail Baryshnikov's The Nutcracker (Rich and Aronson Reference Rich and Aronson1987; Aronson Reference Aronson1989).

Aronson and Agadati met in Paris in 1923 during one of Agadati's European tours. These were financed, not least, from the incomes of the hugely popular Purim masquerade balls that Agadati organized in Tel Aviv together with big Adloyada-Purim parades and Queen Esther beauty pageants—show activities rich in costumes and dancing, yet with a mainstream and less subversively queer aesthetics (Spiegel Reference Spiegel2013, 21–56). Most probably communicating in Yiddish, Boris Aronson designed several costumes for Agadati, mainly for his solo dance pieces featuring typified Jewish characters (Perry-Lehmann Reference Perry-Lehmann1986). All of these costumes worked with the same principle: creating a second skin, the costume reshaped the bodily contours of the dancer to a more geometrical silhouette, and this new outer contour rebounded back onto the dancing. This was another aspect of queering Jewish dance as the contours of Agadati's body were extended and transformed. He became a geometricized figure in a Jewish-themed piece and danced in an angular movement style evoked by the stiffness of the expressionist costume. With the help of the costume, the reshaping or, as I am tempted to say, the queering of the body contour fostered a new and deliberately modernist visuality of the moving body.

The poet and literary critic Yeshurun Keshet, born Ya'akov Yehoshua Koplewitz, in his long text “Agadati's Jewish Dance Art” from the late 1920s—translated from Hebrew to English by Giora Manor and yet another remarkable example of the level of reflection with which art theorists contemporary to Agadati wrote about his concept of modern dance—said the following:

We are used to seing [sic] dance costumes which are more or less decoration, something external, embellishing the dancer rather than the dance, as modern dance is concerned primarily with rhythm and self-expression. Not so Agadati, who regards the costume as an integral part of the dance itself. He quite rightly believes the costume to be an extension,… the external layer of the dancer's body and therefore of the dance. The colors and contour of the costumes are a reflecting-area for light and give the dance the structure of rhythmically moving lit forms.… If, on the one hand, he sacrifices the purity of dance by introducing poetry and theatricality and the use of psychological and spiritual elements, at the same time he enhances it by taking it closer to the art of painting and sculpture by paying great attention to the color scheme and the design he uses, as well as by his subtle feeling for composition. (Manor Reference Manor1986, 22)

Not unsurprisingly, Agadati's visual art approach to dancing made his moving and posing body a favored subject for visual artists of his time, as in drawings by Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov (Perry-Lehmann Reference Perry-Lehmann1986, 112). One of Larionov's watercolor paintings from 1925 shows Agadati in his folk dance creation Ora Glilit, later known as Hora Agadati, one of the earliest Hebrew folk dances (Lapson Reference Lapson1954, 23–24). Agadati developed this in 1924, originally to a traditional Moldavian tune that was later exchanged for a tune newly composed by Alexander Uriya Boskovitz, after he discovered that the first tune was actually that of a Moldavian antisemitic song. The additionally complicating fact that the Hora Agadati, perhaps the most enduring connection between Agadati and dance, even got new steps introduced by Gurit Kadman, reveals again the hybrid character of Israeli or Hebrew folk dance. In some publications, this movement practice was called “Palestine Folk Dance,” thus mirroring the appropriations and political reframing of movement material stemming from both Palestinian and European dance traditions (Kadman Reference Kadman1946).

Another important artistic partner for Agadati was the Israeli artist Reuven Rubin. Born in 1893 as Rubin Zelicovici to a poor Romanian Chassidic family, he, like Agadati, immigrated to the Yishuv twice: in 1912 and in 1923 (Mendelsohn Reference Mendelsohn2006, 13–20). Although he also painted Agadati dancing in his Chassidic-themed choreographies, he is well-known for paintings that focus on dancing in traditional Chassidic contexts in Israel, like Dancing with the Torah at Mount Meron from 1924 or the Dancers of Meron from 1926, which became one of his principal works (Manor Reference Manor2002, 74–75; Reference Manor2005, 152–154). Agadati himself replied to Rubin's dance-themed visual art in the last phase of his own career as an artist: after quitting dancing and turning to filmmaking, he now went back to fine arts, his original field of studies at the Bezalel academy. In the last years of his life, he drew abstract and bird- or floral-themed paintings, often using a silk-painting technique. In some works, however, Agadati dealt with dance topics and tried to reach the aesthetic level of Rubin's painting, thus reflecting how important the earlier artistic cooperation with Rubin had been for him (Raphael Reference Raphael2009, 177).

Reuven Rubin created the stage and costume design for Agadati's dance piece Abraham and the Three Angels (1925, Music: M. Milner). Interestingly enough, the pictorial representations of this performance show a multilayered structure that mirrors the aesthetic principles of Agadati's approach. Because photography of the actual performances was technically not possible in British Mandatory Palestine of the 1920s, Rubin and Agadati combined drawings of costume designs with cutout fragments of photography showing his face and hands. Glued onto the drawing and pictured again, the result is not photography of a dancing body but photography of a montage showing a dancing body. This montage technique was also used for the entire set of Abraham and the Three Angels, when all of the performers’ faces were cut out and glued onto a stage-design drawing to create images that apparently show a group of performers in action and onstage.

Tied to the larger argument of Agadati's queering of Jewish dance, such a montage worked with the idea of an exposed constructedness: various elements are mixed and reframed to create something new, much like Agadati constructed his form of Jewish dance out of existing layers of identity and expression. Mixed, reframed, and deliberately unperfect, both the conglomerate of the montage and the similarly constructed phenomenon of Agadati's Jewish dance queered representations of reality to a degree that this reality was altered, changed, and ultimately transformed.

In the case of Abraham and the Three Angels, which is also known as Sarah and Hagar, Agadati queered convention even further: Despite Agadati's focus on his own male dancing body, which in harsh contradiction to his very first performance often remained cloaked under various layers of costumes, Abraham and the Three Angles was choreographed for a group of dancers, including female dancers. Agadati had casted the latter for the roles of the three angels following the pictorial tradition of Latin Christianity of the West instead of the more common Jewish tradition that angels, mal'achim, are male. Although these casting choices were in line with Christian traditions, they did queer conventional Jewish dance aesthetics.

“An Oriental Vice”

One of Agadati's most controversial pieces, Arab Jaffa (1927), portrayed a Palestinian Arab in Jaffa, Tel Aviv. Much as with his portrayals of Chassidic or Yemenite Jews, he did not refer to a real person or attempt to achieve sociocultural, political, or religious realness. In its idealizing and exoticizing approach, Arab Jaffa is similar to his piece Yemenite Dance, yet in Arab Jaffa he does not refer to any part of his religious or cultural background, even if Yemenite Judaism was different from his own way of Jewishness. The Arab-Jewish conflict and Agadati's approach to this conflict from a Western, allegedly superior, art perspective reinforces the Orientalism of this work immensely. This Orientalism is broadly visible in art and photography in the Yishuv, as portraits of Western Askenazi Jews in Arabian and Bedouin clothes—or, more appropriately, costumes—show. Dor Guez's work on Pre-Israel Orientalism (2015) analyzes these historic pictures from the 1910s–1930s as a Western practice of perceiving the East as an “ensemble of representations he [the Westerner] wished to control and in which he could anchor his superiority over the Easterner as an act of reproducing the power relations between the enlightened European and the failing primitive Arab” (Guez Reference Guez2015, 34).

Being European himself, it was this practice of temporary self-fashioning as Oriental that Agadati used in Arab Jaffa, a piece in which he performed an Arab dandy who, holding a flower in his hand, walks the streets of Jaffa. To quote the Israeli dance scholar Yael Nativ in her analysis of the piece: “Agadati is seen wearing a generic Arab costume: sirwal pants and a vest with ethnic embroidery, a heavy cloth band around his waist and a triangular cloth hat.… Agadati's practices of appropriating Arab identity show an eagerness to structure an authentic local identity based on enchantment with the Arabs who embody it. Agadati, like other artists of his time, saw the Arab body as rooted, earthy and local but also as an imagined existence to be embraced” (Nativ Reference Nativ, Rottenberg and Roginsky2020, 111).

Yet, the piece is even more complicated and has another layer that I would like to analyze as an equally relevant facet of Agadati's practice of “appropriating Arab identity” (Nativ Reference Nativ, Rottenberg and Roginsky2020, 111). I return to a much older text from 1927, a dance review written by the male dance critic Leopold Thaler of a performance of Arab Jaffa in Vienna, published in the German journal Jüdische Rundschau. This review has been quoted many times in Giora Manor's translation, yet Manor has omitted a key word in the text on the dancing Agadati: feminine. The review refers to Arab Jaffa as follows, and I'm quoting my own full translation:

Among the six dance pieces, Arab Jaffa is the most beautiful, the most balanced and artistically the best. In this piece Agadati breaks the purely ethnographic framework and creates a delicate and subtle subjectively viewed study. An Arab dandy with a flower in his hand, all Narcissus, in love with himself, on the edge of the feminine, slightly prancing, lazy and dreamy, always ready to move from beauty to cultureless distortion: relieving himself on the roadside. (Thaler Reference Thaler1927)

The same review described Agadati's body with a homoerotic undertone: “Tall, broad-shouldered, slim, with wonderful hands and long legs, Agadati, in his extraordinarily beautiful and colorful costumes, looks like a fairytale wonder” (1927, 591).

Much of Arab Jaffa remains unclear. We do not know whether Agadati held the flower in his hand during the entire performance or whether he picked it up or dropped it at some point. The various photographs of the piece even differ on precisely which flower he used: Was it a single blossom, a small bouquet, an artificial flower, or a freshly cut stem? And most importantly, Thaler's evocative description of the piece does not explain the background for the Arab dandy “relieving himself on the roadside” (Thaler Reference Thaler1927, 591; German original: am Straßenrand die Notdurft zu erledigen), a phrase referring to an act of urinating in public when no pissoir or toilet is available.

However, while being vague on this point, Thaler's text does give clear links to the homoerotic subtext of the piece. Why else the reference to “Narcissus in love with himself”? Why Agadati “on the edge of the feminine”? I am reading the queerness of this piece through the lens of its review, and through the extremely staged photographs, which apparently almost exclusively refer to the climax scene of the pantomimed action of urinating (Zalmona/Manor-Fridman Reference Zalmona and Manor-Fridman1998, 36). Other photographs show Agadati from behind holding the ominous flower in his left hand and signalling with his right hand, with a ring on his little finger. He glimpses over his shoulder and smiles as if enjoying having his bottom, the unambiguous center of the scene, looked at.

Photo 3. Baruch Agadati in Arab Jaffa (1927). Photo: Atelier Willinger, Vienna, © KHM-Museumsverband, Theatermuseum Vienna.

Agadati's pose with the bottom at the center of attention can be read as a reference to anal sexuality, while the urinating scene is an unambiguous allusion to sensual physicality. However, these scenes reveal more than the narcissism of a flamboyantly self-promoting homosexual male dancer. By performing the role of an effeminate homosexual Arab, Agadati endorsed the orientalist position of European supremacy in which Arabs had a more sensual physicality, were associated with a lack of hygiene and openly practiced nonconformative sexuality (Yosef Reference Yosef2004, 4; Ilany Reference Ilany, Rohde, Braun and Schüler-Springorum2018). In this sense, Agadati's impersonation of a homosexual man in Jaffa was less the performative approximation of the threat of Arab otherness, but rather the blatant embodiment of an Orientalist homoerotic fantasy.

In addition to this reading, Arab Jaffa needs to be interpreted in conjunction with the socialpolitical background of its time; in the first decades of the twentieth century, the Jaffa part of Tel Aviv was a well-known meeting place for homosexual men. It was part of the larger context of homosexual life in British Mandatory Palestine, where homosexuality was never criminalized per se. Only in 1936, and well after Agadati's creation of Arab Jaffa, were acts of sodomy (or unnatural sex) prohibited by British Mandatory law, but this “criminalization of sodomy went unnoticed in contemporary newspapers and seemed not to have changed common practices” (Yonay Reference Yonay, Kraß, Sluhovsky and Yonay2022, 133). During the earlier period of the Ottoman Empire that followed the Napoleonic Code's decriminalization of voluntary anal intercourse between men, recent research (Ben-Naeh Reference Ben-Naeh2005) has revealed male homosexuality was an even more common phenomenon: “In the Jewish communities… male same-sex sexual activity was common among unmarried men to such a degree that the religious authorities suspected that it could occur any time two single men were left unsupervised” (Yonay Reference Yonay, Kraß, Sluhovsky and Yonay2022, 133).

Yet, though commonly and—at least until 1936—legally practiced, homosexuality was heavily excluded from the early Zionist discourse. As Ofri Ilany has shown, in pre-State Israel and in the early years of the State of Israel, male homosexuality was regarded as a threat to the Zionist project because of the constructed cultural connection between homosexuality and the Orient. Rooted in the ideology of an alleged European superiority, Zionist theory and political practice saw in male homosexuality “an oriental vice” (Ilany Reference Ilany, Rohde, Braun and Schüler-Springorum2018) that was dangerous in its approximation to a presumably non-Western lifestyle.

Zionist's anti-Oriental refusion of homosexuality was also motivated by the antisemitic parallel between Jewishness and homosexuality. Following the convincing and influential interpretation of Sander L. Gilman and others (Boyarin Reference Boyarin1997; Pellegrini Reference Pellegrini and Pellegrini1997), the “invention of homosexuality” (Gilman Reference Gilman1991:126) “coincided with the entry of Jews into the Central European bourgeoisie, an entry productive of and complicated by the sexual stigmatization of Jewish men.” (Seidman Reference Seidman2011, 50). Because nineteenth-century antisemitism had developed a distorted portrait of the male Jew as effeminate, Zionism feared that supporting homosexuality would fuel this antisemitic construction. In contrast, Zionist theorists such as Max Nordau, whose work Degeneration (Nordau Reference Nordau1895) prepared the argument for the trial against Oscar Wilde, constructed another body fantasy: the hypermasculine muscle Jew (Nordau Reference Nordau and Tebben2018). This was a direct counterreaction to the view of Jews in the Eastern European ghettos as weak, untrained, unfit bodies and sought to overcome the antisemitic allegation of Ashkenazic Jewish culture as lacking full masculinity (Neumann Reference Neumann2011, 116–149).

Zionism realized the ideal of a strong “New Jew” through the support of gymnastics, sports, and physical education for Jewish men and women (Spiegel Reference Spiegel and Greenspoon2012). With regard to masculinity, however, the Zionist concept of trained and virile men as “New Jews” still followed a European heterosexual mode of masculinity. In the attempt to overcome the antisemitic stereotypes of the effeminate Jew, Zionism had adopted the homophobia that was connected with these stereotypes. The result was the fantasy of the “New Jew,” who, in the male version, was exclusively heterosexual (Yosef Reference Yosef2004, 4).

Only in recent decades has Israel developed its current strongly pro-queer position, and even this is argued, as Ilany shows, in an anti-Oriental way, celebrating the fact that “we are not Iran” (Ilany Reference Ilany, Rohde, Braun and Schüler-Springorum2018, 118). With this distancing from homophobic politics in Islamic societies like Iran, queer and queer-supportive Israelis praise themselves as progressive while simultaneously reactivating a position of Western superiority. In contrast, early Zionism—and Agadati's piece Arab Jaffa showed exactly this—linked homosexuality so strongly to the Orient that the Orientalist perspective also allowed for an emancipatory position for queer identity. In adopting the perspective of the dominant Western immigrant who portrayed an effeminate Arab dandy with a flower in the hand, Agadati—himself intersectionally discriminated against by antisemitic and homophobic discourses—brought his own homosexuality onto the stage, hidden but readable for those who could decipher the cultural code.

Muscle Jew in Drag

A similar self-positioning as a weak, effeminate Jew happened in Agadati's dance series Galut Cycle (early 1920s), in which he portrayed a lasciviously posing Talmud student, the black leather straps of the tefillin wrapped around his bare arm. However, the arm was the arm of the veritable muscle Jew Agadati himself had become in the course of his training discipline (see also Sharim Reference Sharim, Morris and Giersdorf2016). The muscularity of his dancer body explains the unusual wording in Isaac Katz's description of Agadati's very first performance at the Bezalel academy fourteen years earlier, during which Agadati exposed his “then emaciated and puny body”—a body he no longer had when the text was written in 1927. In the Galut Cycle, Agadati posed as a muscle Jew in drag: against the background of Zionism, he approached the non-Zionist context of the diaspora, the Galuth. Not religious himself, but costumed as a religious Jew, striking an eroticized pose, he used this self-fashioning as another signifier for his queer identity.

Adding to the complexity of this practice, Agadati even reappropriated antisemitic stereotypes (Gallner Reference Gallner, Binder, Kanawin, Sailer and Wagner2017) of allegedly typical Jewish postures, gestures, and movements, and turned them into statements of new Jewish pride in dance. Probably the most controversial aspect of his queering of Jewish dance, “he took the lowly, often crude, exaggerated gestures of the antisemitic cartoon and ‘ennobled’ it, lifting it, so to speak, from the rubbish-heap onto the stage” (Manor Reference Manor1986, 8). Reframing antisemitic caricatures of Jewish bodies, movement, and gestures, Agadati constructed what he called Hebrew Dance.

The allegedly typical Jewish expressivity of his movement style, and the assumed parallelism between the angularity of the Hebrew script and the seemingly angular character of his poses, do not stem from a natural reservoir of Jewish or Jewish-Ashkenazi movements. They are a hybrid mixture of various influences combining the quoted gestural material of Jewish dance with a positive reframing of its negative stereotypes. With his queer exaggeration of existing and imaginary movement material, Agadati proudly reclaimed what the antisemitic discourse of the Diaspora had denied the Jew's body, and masculine Jewish corporality in particular (Schwan Reference Schwan2019b, 77). In this sense, Agadati shared the body image of a healthy and strong “New Jew” and combined it with his aim of a masculinization of dance (German “Vermännlichung des Tanzes”), as Klara Blum wrote in a contemporary dance critique of his performances in Berlin (Blum Reference Blum1928).

Remarkably, Agadati even queered the hypermasculinity of the Zionist body culture as his project of Hebrew Dance exceeded the new normativity of male masculinity. He left room for queer appropriations of what Daniel Boyarin in Unheroic Conduct (1997, 23) has identified as the “‘soft’ Jewish masculinity in the Talmud and the succeeding culture of rabbinic Judaism” (Boyarin/Itzkovitz/Pellegrini Reference Boyarin, Pellegrini, Itzkovitz, Boyarin, Itzkovitz and Pellegrini2003, 2). In his dance series Galut Cycle and in Melaveh Malkah, Agadati embraced this soft Jewish masculinity in the social context of male Eastern European Jews, like the homoerotically charged bonds between Talmud students or the similarly homoerotic subcontext of Orthodox Jewish dress codes, hair styling, and religious clothing fashion. Here, Agadati positively reclaimed what the antisemitic discourse of the nineteenth-century had disregarded as incomplete masculinity in Askenazi culture, and by incorporating it as a Zionist and homosexual male muscle Jew, he gave Hebrew Dance its ultimate queer twist.

In summary, Agadati queered the linkage of dancing and Jewishness, and Jewish religious traditions of dancing in particular. He approached these traditions from his perspective as a nonobservant, secular Jew, and his queering was related to both his sexual identity and to the principles of his aesthetic practices. A marginalized closeted homosexual Jew himself, Agadati successfully launched a deconstruction of established links between Jewish body culture and dancing. Aesthetically, he disconnected, shifted, and changed these links to create Hebrew Dance as a new and inherently queer phenomenon.

Agadati's queering of allegedly essentialist categories like gender, as well as national and religious identity, was in continuity with traditional Jewish religious practices of questioning, discussing, and quoting and re-situating older texts in contemporary situations. As in Talmudic discussions, Agadati's repositioning and queer appropriations of Jewish traditions did not pretend to provide an ultimate answer. On the contrary, the legacy of his dance art is the opening of fixed categories of Jewishness, Yiddishkayt, or Yahadut, and how they might be related to dance and movement (Gitelman Reference Gitelman2009; Boyarin Reference Boyarin2019, 130–151).

In this sense, Agadati's approach even questions linkages of Jewishness and movement in the contemporary Jewish dance world and in Jewish dance studies, as his queering of Jewish dance exceeds problematic and under-reflected categories of community, identity, and tribe as well as the even more dangerous notion of inherited “Jewish” dance movements (for the questioning of essentialist categories, see Rossen Reference Rossen2014, 3–4, 12). Attempts to read Agadati's performances as an embodiment of the “timeless pious Jew” or as a reconnection to “ancient roots and authenticity” (Jackson Reference Jackson, Jackson, Pappas and Shapiro-Phim2022, 3) miss the citational and constructive character of his dance aesthetics. Almost ironizing such contemporary fantasies of Jewish embodiment in advance, Agadati approximated allegedly typical Jewish gestures and poses from a distance by appropriating and transforming this movement material in a “queer play of self-display” (Schwadron Reference Schwadron2018, 19). He did not dance in an authentic Jewish manner but questioned the very presuppositions of authenticity through his queer take on traditional Jewish dance material mixed with a seemingly queer shift of the antisemitic distortions of this material. With Hebrew Dance, Agadati approached Jewish corporality from the side and celebrated the queer citationality of this approach.