1. Introduction

As the years crept up, the elderly of the Renaissance increasingly came to depend on the younger generation; but how could the old make sure that the young would provide them with a decent old age? The elderly may have been tempted to hand over their property inter vivos, for instance to allow sons and daughters to establish their own household, and then expect to be taken care of in return. But by doing so, the elderly faced the dilemma of ‘poor parents, rich children’: by handing over the reins to the young, the old exposed themselves to the risk of neglect. Popular images, such as the one depicted in Figure 1, explained to contemporaries what could happen if an elderly person failed to employ a strategy for old age.Footnote 1 Having transferred his property to the younger generation, the old man had lost his position as head of the family and had to suffer the humiliation of having to eat alone, sitting at a side table, and being ridiculed by his grandson. The dilemma has also left traces in historical records: some elderly employed a strategy of using a specific agreement – the retirement contract – that allowed them to hand over property on condition of respectful treatment and proper care during their old age. If this condition was not met, a law court could annul the transfer, returning the property to the original owner. A second strategy open to the elderly was to promise the young a transfer postmortem in a will on comparable conditions. By doing this, the younger generation had a prospect of eventually being rewarded, while the older generation stayed in control of their possessions and caregivers, since it was possible to modify or withdraw the will. The men and women who are the focus of our paper established strategies to retain agencyFootnote 2 during old age, either by entering into retirement contracts with the young, or by recording wills.Footnote 3 Planning for old age was probably quite common but its traces in the historical record are not always easy to find. To study this subject, we have cast a wide net and investigate a variety of towns in the Low Countries to find out how the elderly could secure support from the younger generation, while at the same time retaining agency. In our discussion, we focus on legal instruments – wills and retirement contracts – and demonstrate how these allowed for dictating future relations with relatives and non-relatives. We also investigate the type of care in old age that was laid down in contracts. Looking at the contractual conditions allows us to see what the elderly deemed important during their final years, and what reasons they could have for rewriting wills and terminating retirement contracts.

Figure 1. ‘Poor parents, wealthy children’. Carton, Leiden, c. 1520–1530. Museum de Lakenhal Collection, inv. no. S 5751

The use of wills and retirement contracts is sometimes linked to the idea that some of the elderly were at risk of spending their final years in misery.Footnote 4 This may well have been the case in urban settings such as the Low Countries,Footnote 5 where, among other factors, the dominant idea that people should live in nuclear households could lead to hardship. During the Renaissance, elderly people were no longer expected to move in with their adult children.Footnote 6 Rather, they were required to live autonomously and fend for themselves as much as possible, even if they had children living nearby. The proximity of offspring was not so self-evident either: parents may have outlived their children,Footnote 7 or have seen sons and daughters move away, usually to other towns looking for work.Footnote 8 The considerable likelihood that they would have no next of kin living nearby is a second reason why the urban elderly may have been at risk. A third and final reason why they may have faced the threat of a miserable old age was the high proportion of people who never married and did not have any offspring: the proportion of singles has been estimated to have been up to one-third of the adult population in towns.Footnote 9 These singles were especially at risk of ending up living alone, and therefore may have required strategies to ensure old-age support.

Of course, not everyone used wills and retirement contracts to ensure a decent old age. Many elderly persons would simply have relied on family and friends, and the strategies we discuss were probably not the most usual way to arrange eldercare – although quantification of their importance is unfortunately not possible. First, we only have the contracts that were recorded in writing and have been preserved and are unaware of the oral agreements discussed in section 2. Second, even if we could somehow count all instances where wills and retirement contracts were used to negotiate eldercare, this would still not provide an indication of their importance. The mere option to seek eldercare with others than the next of kin, by using retirement contracts and wills, already empowered the elderly because they were not destined to accept whatever assistance their offspring was willing to provide. Instead, they could simply threaten to turn to other relatives, or non-kin, who offered to treat them better during their final years. This alternative is likely to have been brought up in many families during discussions about parents’ final life stage and may thus have also played a role in moulding structures allowing for kin-based welfare.

Intergenerational support was not at all self-evident and scholars have rightfully warned against an image of a ‘supposedly golden age of kin-based welfare provision’ in the past.Footnote 10 Eldercare did not always come naturally, and therefore the elderly sometimes used contracts such as the ones central to our study, while other seniors had to rely on safety nets provided by the community or poor relief institutions. In addition to debunking ideas of unconditional filial love, our focus on the agency of the elderly contributes to a growing field of old-age studies that moves away from the image of ‘helpless’ elderly people in the pre-modern world who depended on the mercy of the younger generation,Footnote 11 and instead highlights how men and women strove for independence during their old age.Footnote 12 Writing about early modern society, Lynn Botelho states that ‘an independent old age seems to have been the goal of the elderly everywhere, and in every station of life’. She also notes that the main goal of the elderly was to make sure that ‘their care and maintenance were ultimately derived from their own efforts’.Footnote 13 Her claims link up nicely with contemporary studies highlighting the importance of independence and empowerment for the well-being of the twenty-first century elderly.Footnote 14 As we will show, a desire for agency is also evident in wills and retirement contracts from the Renaissance.

2. Outline, sources and historiography

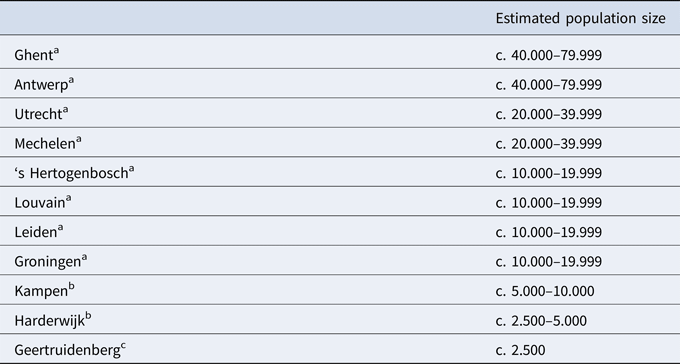

To study strategies for old age, we use wills and retirement contracts from urban settlements, covering large towns such as Antwerp and Ghent, medium-sized settlements, such as Utrecht and Mechelen, and a range of smaller towns (see Table 1 and Figure 2). Our sources apply to many regions and suggest that these specific strategies for old age were employed throughout the Low Countries. We have restricted ourselves to the period before 1572, when the principalities Holland and Zeeland began their revolt against King Philip II of Spain (1527–1598) causing the political union of the Low Countries under Philip's rule to crumble. Four years later almost all principalities of the Low Countries had joined the efforts to break away from Spanish rule. During the following decades, many towns were caught up in regime changes. For instance, Antwerp was ruled by Calvinist rebels from 1577 until 1585, when the town was reconquered, and Spanish rule was re-established. Eventually the Low Countries were divided in the Dutch Republic in the North, ruled by Calvinists, and the Southern Low Countries, under control of a Spanish, Catholic regime. We focus on the period before these profound political and religious changes, when the Low Countries were under Catholic rule, and the vast majority of the population still obeyed the Church of Rome.

Figure 2. towns mentioned in the text. (1) Groningen, (2) Kampen, (3) Elburg, (4) Harderwijk, (5) Utrecht, (6) Leiden, (7) Geertruidenberg, (8) 's Hertogenbosch, (9) Antwerp, (10) Ghent, (11) Mechelen, (12) Leuven.

Table 1. Estimated population size of towns, c. 1500

Sources:

a J. de Vries, European Urbanization 1500–1800 (London, 1984), appendix 1.

b A.M. van der Woude, ‘Demografische ontwikkeling van de Noordelijke Nederlanden 1500–1800’, Nieuwe Algemene Geschiedenis der Nederlanden vol. 5 (Haarlem, 1982), 102–68, 136.

c R. Fruin (ed.), Informacie upt stuck der verpondinghe (Leiden, 1866), 524–25.

Wills and retirement contracts were not recorded systematically; testators who wanted to deviate from the laws of inheritance did not necessarily have to record a will, but could also make an oral statement in the presence of witnesses. They could do so years before they expected to pass away, but also when lying on their deathbed. Such promises escape the eye of the historian. The same is true of retirement contracts, which could also take the form of oral agreements, and yet were enforceable by law.Footnote 15 Fortunately, wills and retirement contracts have also been handed down as charters, while others were recorded in a variety of documents, including aldermen's books and notarial records. Furthermore, wills also appear as a part of marriage contracts, and retirement contracts are sometimes included in records of real estate transfers, and in wills.Footnote 16 Our source material is taken from this diverse collection of documents.

The strategies we focus on involved a quid pro quo: eldercare in return for property. This also means that the strategies central to this study were open to the propertied classes; for c. 80 per cent of the population using wills and retirement contracts to take charge of their final years was thus an option.Footnote 17 It is likely that a large proportion of those who did so came from the middling layers of society,Footnote 18 although evidence of the social status of contracting parties is unfortunately scarce. The few occupations mentioned by the elderly are maidservant, blacksmith's widow, and ropemaker; among the caregivers was a mason promising to look after an old man, as well as a priest, and a schoolmaster.Footnote 19 Their wealth is even more difficult to assess because our sources do not give the value of the transferred property. Yet, as will become clear further on, the eldercare which the men and women central to our study negotiated was adequate rather than lavish, and therefore it seems unlikely that they were excessively wealthy. The rich would also not have required wills and retirement contracts to ensure they could spend their final years in comfort, as they could simply live off their wealth and hire servants to provide eldercare.Footnote 20

Our sources do not give the ages of the men and women who entered into these contracts, yet there can be little doubt that most did so because of their advancing years. This is, for instance, evident when we look at the family relations of parties to contracts that will be discussed in the following sections. Out of twenty-nine contracts between kin, twenty-seven were between senior and junior generations. Mothers, fathers, aunts, and uncles reached agreements with daughters, sons, nieces, and nephews. The junior parties were often married and in all cases of legal age, which suggests the seniors would at least have been on the doorstep of old age. The two remaining contracts were between a woman and her stepdaughter, and one between a man who suffered from ‘ailments’ and his siblings. Only in these latter cases can we not rule out the recipient of care being still relatively young.

Previous research has shown that testators were not only concerned with pious bequests aimed at the salvation of their souls, but also with the proper and peaceful distribution of their assets.Footnote 21 Indeed, according to experts such as Jacques Chiffoleau and Marie-Thérèse Lorcin, starting in the late medieval period wills were increasingly used and seen as secular documents intended primarily for the division of an inheritance. As a result, in this period an increasing number of wills were drawn up and rewritten by young people in the prime of their lives, as well as by married couples. Joint wills typically entailed provisions for the longest living spouse, to prevent them from falling into poverty after losing a husband or wife.Footnote 22 Due to these characteristics, David Cressy, among others, has argued that wills are invaluable sources for research on the evolution of kinship relations, for they are ‘sensitive indicators of family awareness, mapping out the effective kin universe of testators’.Footnote 23 Of course, this also applies to other types of networks and social relations, which could be based on living in the same neighbourhood, practising the same or a similar profession and shared religious practices.Footnote 24 Although they cannot shed light on the full range of the testator's network, wills are beyond doubt indicative of those family members and non-relatives considered most important at a critical moment in the testator's life cycle.

Wills were not only expressions of social networks, they were also used to shape social relations. In the historiography on old age, wills are regularly mentioned as legal documents that could be used for arranging care in old age. For instance, Ilana Krausman Ben-Amos stated that wills could be ‘a powerful tool, [and] inheritance portions could also be used as forms of pressure on offspring to comply with parental wishes or plans’.Footnote 25 Likewise, Ariadne Schmidt has pointed out that testaments were used by fathers to ‘discipline children’ by stipulating they take good care of their surviving spouse.Footnote 26 How wills were used to secure care in old age depended to a large extent on the degree of freedom to manage one's own property. In most areas of the Low Countries, both men and women who had reached the age of majority could use a will to express their wishes as to how, to whom, and under what conditions, their capital, movable and immovable property, jewels and other personal belongings should be distributed after their death. Moreover, even though the legal system often required all women to be represented by a male guardian, single women generally had a right to their parents’ inheritance without having to marry, and they were allowed to transfer their property independently as testators.Footnote 27 On top of that, although the complete disinheritance of children, spouses and the closest blood relatives was usually illegal, people were free to leave remarkably generous legacies to beneficiaries outside their circle of legal heirs.Footnote 28 Wills were powerful tools for arranging care in old age because they were effective only after the death of the testator involved. Up until death, they could be changed with the stroke of a pen; adjustments to wills could easily be made, and at minimal expenses, by adding a codicil. Even oral declarations of a change of heart (in the presence of witnesses) were considered legally valid.Footnote 29 This specific feature allowed testators to make bequests conditional upon the beneficiaries providing ‘service and support’ for the remainder of their lives.

In contrast to wills, retirement contracts allowed for donationes inter vivos; in exchange for promising care in old age, the younger generation immediately received the promised property.Footnote 30 We know relatively little about their use in an urban setting. In medieval Genoa such contracts were used to hand over property to the younger generation and in particular to prevent sons-in-law from neglecting their parents-in-law.Footnote 31 Retirement contracts have also been mentioned in research on old age in France, in several cities in Burgundy, and also on the Mediterranean coast (Montpellier) and Atlantic coast (Caen).Footnote 32 In Central Europe these contracts existed in Hungarian towns as well,Footnote 33 and in Basel, which is currently the city of which we know most thanks to Gabriela Signori's study of 90 retirement contracts from the second half of the fifteenth century.Footnote 34 Her research shows that retirement contracts not only allowed the elderly in Basel to negotiate care in old age with relatives, but also with non-relatives,Footnote 35 which may indicate their lack of family members to fall back on in their old age. The tax assessments of the inhabitants of Basel entering into retirement contracts suggest they came from the ‘middling sorts’ or even slightly below and that they used what little property they had to secure their livelihood during old age.Footnote 36 However, to what extent the elderly in cities elsewhere used similar strategies for old age, and what these looked like, is largely unknown. This is also true for the relatively urbanised Low Countries, where the use of retirement contracts has been noted in the towns of Ghent and Kampen, but has never been the subject of serious investigation.Footnote 37 This lack of urban studies, in the Low Countries and in Europe in general, is all the more remarkable considering that scholars have long established that retirement contracts were common in the European countryside, and these have been studied at length to understand the transfer of property between generations, as well as retirement among the peasantry.Footnote 38

3. Family

Did elderly men and women require strategies to ensure the support of their relatives? Intuitively one would perhaps think not and assume that strong family ties helped them obtain care in old age. Yet social historians have pointed out that families of the Renaissance were far from homogenous groups and characterised by constant bargaining. As a consequence, they rarely distributed resources evenly.Footnote 39 Negotiations are evident in retirement contracts, such as one from Kampen. The elderly man Reyner transferred his property to his daughter and son-in-law because he was ‘old and no longer able to make a living’. He did so on the explicit condition that the couple would maintain him for the rest of his life.Footnote 40 By opting for a retirement contract, the senior man remained in control; if his daughter and son-in-law did not treat him well enough, the court could order them to return the property to Reyner. Whether he had reason to believe his daughter and son-in-law might not treat him properly is unknown. Other contracts reveal existing tensions though. Mette, from Harderwijk, transferred her property to her daughter Aeltgen, who would ‘maintain her as long as she lived with food and lodging, clothing and anything else she might require’. The contract also stipulated that ‘if the two did not get along, Aeltgen would pay 8 guilders per annum’ – c. 30 day wages of a skilled worker – until Mette died.Footnote 41 Mother and daughter seriously considered that cohabitating might not work out, and therefore added a clause that would provide an ‘exit strategy’. Something similar is seen in a retirement contract from Amersfoort where a son and daughter-in-law agreed to take care of the mother Maria ‘in a reasonable way and as well as possible, as good children should’. Such an appeal to filial love does not feature in many contracts and suggests that the mother was not entirely certain that the couple would provide her with a peaceful old age. Perhaps that is why the contract also stipulates that should the mother no longer want to cohabit with the couple, they should pay her an annual sum as well as give her ‘a bed with bedding, a pot, a kettle and a bucket’.Footnote 42 This provided Maria with the option to find an alternative place to spend her final years, for instance by moving to another household, where she would pay for food and lodging. Yet, she might also have contemplated paying for food and lodging in an institution, which usually also required the elderly to bring their own bed. Spending one's final years as a paying customer in an institution was not unusual. In Kampen the woman Fije entered into a retirement contract with her son Ghijsbert. If the relationship were to sour, he would arrange a corrody for her: a commercial care package, where a third party – usually a convent or hospital – was paid to provide lifelong food and lodging.Footnote 43

Relations with blood relatives may sometimes have been so difficult that a retirement contract was deemed necessary, but several contracts also show a healthy portion of distrust of non-blood relatives – especially in-laws. A mother from Harderwijk recorded a retirement contract with her daughter and son-in-law and added the condition that if she would survive her daughter, the husband would either continue to care for her, or return the property. A few years later, when the daughter had indeed passed away, a new contract was recorded that allowed the son-in-law to either continue cohabitating with his mother-in-law, or if this would not work out simply pay her a weekly sum.Footnote 44 A similar ‘opt-out’ is visible in Kampen, where Willem Jansz stipulated that if he outlived his daughter Anne, his property would be returned to him; continuing to cohabitate with his son-in-law Berent was clearly out of the question. The feeling was mutual: Berent happily agreed to this construction.Footnote 45 The elderly could thus also use retirement contracts to plan ahead, by anticipating what should happen if a trusted caregiver were to die. By prescribing what would happen in such a scenario, they could avoid ending up living with a son-in-law, who might also decide to remarry, thus completely changing the living situation of the senior. To be sure, daughters-in-law were treated with caution as well. Jutte, also from Kampen, stipulated that she would receive a large sum of money if her son Willem passed away, so that she could find a new place to stay if she decided she could not bear living with her daughter-in-law.Footnote 46 A woman from Arnhem stipulated that she could reclaim the gift to her son both if he did not take care of her and if she outlived her son, and ended up with her – apparently dreadful – daughter-in-law.Footnote 47 Seniors could even go as far as already appointing someone to take over after the death of the caregiver. The widow Willempken, from Geertruidenberg, entered into a retirement contract with Aliken. If the latter were to die, the contract stipulated, one Peter was required to provide the widow with care in her old age.Footnote 48

Retirement contracts allowed the elderly to take charge of their final years, and wills were used in a similar way. The will documenting the last wishes of the widowed Kathelijne, from Mechelen, leaves little to the imagination when it states that her nephew Anthonis would only inherit if he continued taking care of Kathelijne for ‘the remainder of her life’. He was to do so by providing her with ‘food and drink, clothing, shoes and anything else she might need’. This comes close to the conditions mentioned in most retirement contracts – prescribing food and lodging – but is also different in one important aspect: Anthonis would not receive his reward until his aunt passed away. This situation put Kathelijne in a strong position, as her nephew undoubtedly knew very well that if he were to fail to fulfil his part of the bargain, Kathelijne could easily disinherit him.Footnote 49

However, wills often also reveal long-standing and much appreciated relationships of support. For instance, according to their will the Mechelen couple Anthonis and Liesbeth were highly indebted to their niece Johanna, who lived with them. While their maid would inherit but four guilders – scarcely more than a week's wages – Johanna could expect a decent reward of 100 guilders for all the ‘effort, work and services she had already been doing daily’. It is of course highly likely – though not specified as such – that Antonis and Liesbeth expected that Johanna would continue taking care of them for the remainder of their lives.Footnote 50 Likewise, the will of the widower François, also a resident of Mechelen, stipulated that his daughter-in-law would only inherit the promised sum of 100 guilders if she continued her ‘obedient and loyal service’ to his household until his death.Footnote 51 And lying on her sickbed, the Mechelen widow Cornelia chose her daughter Adriana as the heir to her estate, albeit on the explicit condition that she would continue to ‘maintain’ her mother for the remainder of her life, providing her with ‘food and drink as well as with the support and necessities she might be needing in the future’.Footnote 52 In Leiden the widow Jannetgen recorded her wishes. She bequeathed her estate to her daughters Maritgen and Aefgen because the two had supported her for the past eleven years ‘with their manual labour’, and without their help ‘she would have suffered misery and want because her old age and infirmity prevented her from making a living’. In addition to Maritgen and Aefgen, the old woman had another five children, who apparently were less involved in taking care of their mother. The testament named the two daughters as the main beneficiaries, but on condition that they would continue to take care of the elderly woman as they had done before.Footnote 53 The testament does not make clear what would happen if the two daughters did not continue to serve Jannetgen, but it stands to reason that the testator would simply change her will by adding a codicil.

The above-mentioned bequests come from proper wills: lengthy official documents typically written on vellum or paper. An easier and less expensive way to ensure support was to have a conditional bequest recorded by the local authorities. We encounter this practice in Ghent. The couple Jan de Somer and his wife Lijsbette van Parijs promised Marikine van Parijs – most likely a niece – a handsome sum of money ‘for past and future services’. She was to receive half on the death of Jan, and the other half when Lijsbette passed away.Footnote 54 This construction allowed the elderly couple to offer a reward to Marikine without going to the trouble of recording a will. She was allowed part of the estate as a reward for past and future services. Indeed, sometimes wills and retirement contracts were ratified many years after the younger generation had begun to care for the elderly. The last wishes of Lisbette van den Kerchove, from Ghent, stated she had already been maintained by her daughter and son-in-law for 19 years when a retirement contract was recorded that granted all of Lisbette's property to the couple – on the condition that they would continue to take care of her.Footnote 55 A long-standing relationship also already existed when the woman Jozina, from Utrecht, bequeathed her assets to her niece, who had cohabitated with her for many years and had served her well.Footnote 56

It would be a mistake, however, to think that wills and retirement contracts merely functioned to secure care for the older generation; they also served to prevent conflicts among heirs. Such conflicts were likely to arise when parents rewarded one particular heir for supporting them during their old age because such rewards cut into the inheritance of other family members, who might object to the preferential treatment. This probably explains why in 1545 the adult children of Jan and his wife Margriete, from Mechelen, were present at the time when their joint will was written. According to the document, their (only) daughter Adriana would receive an extra legacy of 100 guilders – close to half a year's wages of a skilled worker – as well as a bed and bedding upon the death of the longest living parent. The will stated that Jan and Margriete left a larger legacy to her as compensation, and out of gratitude, for the ‘services and support’ they had been receiving and expected to continue to receive for the remainder of their lives. Her three brothers apparently thought it reasonable that their parents endowed their sister with an extra legacy and agreed with this construction.Footnote 57 In a similar way, family members appeared as witnesses to retirement contracts. Thus, when the couple Ghiselbrecht and Lysbette, from Ghent, agreed to take care of the woman Katheline – there is no reason to assume they were related – Katheline's conditional transfer of all her possessions was sanctioned by her family members.Footnote 58 As we will see, alienating property to non-relatives was not unusual, but it could require even more careful planning.

4. Non-relatives

If contracts allowed people to negotiate care in their old age with family members, could this also be done with non-relatives? Servants are often mentioned in wills as recipients of bequests. The practice of leaving legacies to servants was common in Ghent, where 214 out of 419 wills (51 per cent), covering the period 1400–1450, contained gifts to servants, who usually received relatively small portions of the inheritance.Footnote 59 Elsewhere lower shares were found, such as in Mechelen, where servants were mentioned in only 4.1 per cent of wills. Our sources do not always provide hard evidence that such gifts were intended (in part) to motivate caregivers to continue to provide top-notch care during old age. Yet, it is of course quite possible that testators tried to motivate their staff by candidly alluding to the reward loyal personnel could eventually expect. A bequest by Thomaes van den Zantberghe, from Ghent, to his servant Marie is quite explicit though. The maid would receive a considerable sum of money, a dish, two of his best silver spoons, and the bed she was already using ‘because of the services she had performed and would continue to perform’. The bequest would be cancelled if Marie were to leave his service, unless she did so to marry.Footnote 60 This highly appreciated maid received a conditional gift to secure her continued services. A similar motivation can be suspected in the case of the widow Katheline, also from Ghent. She promised Jan, who had served her for eight years as master journeyman in her smithy, that he would get all the tools, the bench and the grinding stone, ‘for services he had performed, and would continue to perform’.Footnote 61 Perhaps the widow had come to depend on the young blacksmith after her husband died? The promise of inheritance may have been an attempt to secure Jan's services and prevent him from leaving Katheline to set up his own smithy. The need to ensure continued service sometimes required testators to make adjustments to their wills, as is seen in a testament of the couple Jan and Alijdt from Leiden. In 1558, they made each other the universal heir, but they also stipulated that after the death of the surviving spouse, their two live-in servants, Willem and Marie, would receive 100 guilders each (equivalent to 250 day wages of a skilled worker). This was to reward them for their ‘lengthy faithful service and labour, which they had done for many years, and would continue to do’.Footnote 62 The testators may have expected that the promise of this hefty reward would tie the servants to the household. This worked remarkably well because when Alijdt passed away shortly after 1558, Jan went on to marry none other than the servant Marie. The newly-weds recorded a new will, in 1560, which confirmed the servant Willem's right to receive 100 guilders after Jan's death, and in addition stipulated that he would receive another 50 guilders after the passing of Marie.Footnote 63 It seems reasonable to assume the latter portion was to ensure Willem's continued services, including after Jan passed away, leaving behind his former servant and now second wife Marie.

In addition to wills, retirement contracts reveal how the elderly could solicit caregivers from outside their family circle and spend their final years with non-relatives. The latter is evident in the retirement contract of Gheert from Kampen. In return for food and lodging, he transferred his house to the couple Henrick and Elsken. That they were not related is suggested by the stipulation that if the old man should fall ill and need to be cared for by a relative, Henrick and Elsken would also maintain that caregiver; even though next of kin were available, Gheert had decided to spend his old age with non-relatives.Footnote 64 To give another example, the Harderwijk resident Egbert transferred his yard to Peter van Bissel and his wife Nyse; the couple would provide for Egbert in return. The contract mentions Egbert's son, Goirt, who was present when the retirement contract was recorded by the city's aldermen. In fact, the son was co-seller of the yard, and was promised the payment of a handsome sum over the course of three years. The son and elderly father did not opt for a ‘familial’ old age arrangement; unfortunately, the source offers no clue as to why Goirt did not take care of his father but left this task to non-relatives.Footnote 65 A similar arrangement was made by the woman Merge, from Elburg, who transferred her property to the couple Aert and Geyse. The couple were to maintain Merge and agreed to give a sum of money to her daughter Dirkyn after the old woman had passed away.Footnote 66 Why her daughter did not take care of her during her old age is unclear; was she unable to do so, or unwilling? A daughter is also mentioned in the retirement contract between the woman Verkateline, from Ghent, and the man Maes, who received all of her property – he does not appear to have been related to Verkateline. Her daughter is mentioned in the contract because she had agreed to the gift, on condition that she would receive a sum of money after her mother passed away.Footnote 67 These examples demonstrate how retirement contracts allowed the elderly the freedom to negotiate whom to spend their final years with and if necessary even to surpass kin.

5. Conditions

Wills and retirement contracts not only reveal whom the elderly decided to spend their old age with, but also the additional demands they had for their final years. Retirement contracts provided for food and lodging even though they hardly ever specified diet and accommodation requirements; apparently, there was a communis opinio as to what was reasonable. Fortunately, there are a few retirement contracts that do include additional details, such as the provision of clothing and shoes, and bedlinen. The widow Gryete, from Arnhem, not only demanded shoes, but also trypen – protective overshoes.Footnote 68 Other contracts show that the elderly demanded fuel and light, so they could be comfortable during winter.Footnote 69 When the Louvain widow Alijdt transferred her possessions to her stepdaughter Lijsbetten, the contract prescribed that she should be maintained ‘in such a way that she has no reason to complain (becroenen)’.Footnote 70 Her townsman Arnd had a more elaborate list of demands: ‘hot pottage prepared twice a day, well-prepared food, fire and light’, as well as ‘half the fruits growing in the garden’. In addition, his caretaker was to wash and wring his clothes. And should he fall ill, he would be allowed to stay in a hospital for up to a month.Footnote 71 Gerrit, from Harderwijk, was also quite demanding: his caretakers were expected to provide him with the same type of shoes and bedlinen they used themselves, and with respect to clothing he insisted on the best locally produced cloth.Footnote 72 Gerrit apparently feared his caregivers would dress him in rags, and he was not the only one with concerns about his social status. The Antwerp resident Willem demanded ‘food, drink, clothes, shoes, and all other necessities, in sickness and in health, in agreement with his social status’.Footnote 73 And when Jan and his wife Lijsbeth, from the village of Gierle (about 30 km east of Antwerp), transferred their property to their son, the priest Henricke, he not only had to promise to look after his father and mother for as long as they lived, providing them with food, drink, clothing, shoes, bedding, in sickness and in health, but also to do so in agreement with their social status, and to bury them accordingly.Footnote 74 A proper burial was of crucial importance, and instructions were written down in many retirement contracts and wills. The caregiver for Jehanne, a resident of Antwerp, for instance, ‘would bury her and take care of her funeral, will, bequests and settlement of debts’.Footnote 75 And Jan, a single man from Mechelen who shared a household with the couple Rombout and Petronelle, stated in his will that ‘considering the good deeds, services and support’ he had been receiving while lying on his sickbed, he would endow the couple with all of his possessions. However, the two would only inherit if two conditions were met: they had to continue taking care of Jan, ‘as long and as often as necessary, until his death’, and they also had to arrange for a proper burial.Footnote 76

Concerns about social status were not uncommon, and the same is true for treatment during old age. In this respect, contracts provided the elderly with agency, as is, for instance, demonstrated by a contract from Arnhem, which stipulates a specific task that the caregivers should perform. Jan Fess and his wife Willemken entered into a retirement contract with the couple Jan Egbertss and his wife Anna. They would provide the elderly couple with food and lodging and would ‘help them on the toilet, and off again, regardless of the hour of the day’.Footnote 77 The widow Gertruyt, also from Arnhem, entered into a retirement contract with her daughter and son-in-law, and explicitly stipulated the daughter ‘would not put her in a hospital’.Footnote 78 Apparently, to Gertruyt, the idea of eventually ending up in a nursing home did not appeal at all. Other elderly people also looked further ahead: a widow from Harderwijk who was maintained by an unrelated couple stipulated that if the wife passed away, the husband would have to remarry so his new wife could take care of the widow.Footnote 79 That these stipulations were not dead letters, but were actually enforced, is shown by several examples. In Harderwijk, the man Coman transferred a life annuity to the woman Wychmoet ‘and thus Wychmoet redeemed Gerit from the obligation to provide food and lodging’. It seems reasonable to assume that the death of Wychmoet's husband had led to the termination of the retirement contract; as a widow she did not want to cohabitate with a single man.Footnote 80 The death of a spouse also led to the termination of a retirement contract in Ghent: after eleven years, the arrangement between the elderly Lisbetten and her niece and her husband was terminated. It seems this decision was prompted by the death of the niece, which had left her widower with the task of caring for Lisbetten; the latter received her possessions back.Footnote 81

Even though the elderly could be picky when it came to caregivers, they also valued company. The bequests to servants mentioned earlier on condition that they served until the death of their master or mistress should not only be seen as a way to secure services, but also to ensure they had company. This strategy is, for instance, evident in a slightly later testament, from Bois-le-Duc, where the servant Agnes would inherit on condition that she was still living with Hester when the latter passed away.Footnote 82 In addition, nieces and grandchildren often joined the household of older relatives to provide support and – arguably – also to provide company.Footnote 83 The will of the childless couple Geert and Liesbeth, from Mechelen, suggests that they maintained a close relationship with Liesbeth's son from a previous marriage. Apparently, his daughter Johanneke – Liesbeth's granddaughter – had been living with the couple for quite some time. In this way, Geert and Liesbeth relieved the household of Liesbeth's son of the burden of childcare, and at the same time secured themselves an extra pair of hands and an excellent cure for loneliness.Footnote 84 This aspect is also seen in a slightly later will from Leiden, where the widow Jaepgen bequeathed assets to her son and daughter-in-law, but on condition they continued to live with her up to the time of her death.Footnote 85 Gheert, from Kampen, had the more specific demand that he should eat at the dinner table of his caregivers.Footnote 86 Having to suffer the humiliation of eating with the servants, or alone, during old age, amounted to social decline; the elderly could safeguard themselves against this by recording a contract.

6. Conflicts

To demonstrate the agency of the elderly we now turn to cases where men and women cancelled contracts because they were disappointed with the care they received in old age. Evidence of testators doing so is scarce. As mentioned before, this is likely because it was so easy to revoke bequests, and therefore this did not leave much evidence in the historical records. To have a retirement contract terminated required filing a complaint with the local law court. The clearest examples of lawsuits we have are from Leuven, where the widow Yde filed a complaint. She explained to the law court how she ‘suffered great illness’ and was at risk of ‘withering away’, and therefore she had transferred her property to Arnt, but on condition that he would provide care for her in her old age. But ‘Arnt did not do this and left her to suffer want’. Yde would ‘prove this with the help of her neighbours upstairs and downstairs’, who were aware of the situation because she frequently had begged them to help her out. After hearing the neighbours’ testimony, the court decided to terminate the retirement contract, and Arnt lost the property.Footnote 87 In Kampen the widow Clara had the retirement contract with her daughter and son-in-law terminated because they ‘did not manage to fulfil the conditions’. These were not at all exorbitant, as Clara should merely be provided with food and clothing. It rather seems that a pre-existing conflict may have played a role in the termination of the contract; judging from a dispute there was already bad blood between the three about the settlement of an estate.Footnote 88 In another case from Kampen, the brothers Ghijsbrecht and Martten struggled to come to terms with their mother Fije. Ghijsbrecht agreed to maintain her for the rest of her life, but on condition that if Fije could not stand living with her son, he would buy her a corrody. It did not take long for this scenario to become reality: just one year later, the original contract was stricken from the record, most likely because the two did indeed not get along. Ghijsbrecht agreed to pay 50 Joachimsdaalders – almost 200 day wages of a skilled worker – which were used to purchase food and lodging for his mother.Footnote 89 Law courts did not always rule in favour of seniors though. Jan, ‘an old man’ from Leuven, had entered into a retirement contract with his nephew. He quickly realised this was a mistake because his caretaker was a butcher and lived in a ‘slaughterhouse where meat and intestines were handled, which smells so bad’ that Jan could not stand it. His plea to have the contract cancelled fell on deaf ears though; his nephew convinced the law court he took excellent care of his uncle and was not in breach of contract.Footnote 90 In these cases, the elderly were present to file the suit, but in Groningen the old woman Ffye, who had entered in a retirement contract with her niece, had already passed away when her heirs began a lawsuit. They complained that Ffye had overlooked her four sisters when she entered into a retirement contract with her niece. Eventually the dispute went all the way to the high court of Groningen; Duke Charles of Guelders (1467–1538) issued a sentence. One of the claims the plaintiffs made was that the next of kin were unaware of the retirement contract, even though common law prescribed that they should have been notified and offered the opportunity to step in: ‘whoever issues a retirement contract should first offer it to the rightful heir three times, and if the rightful heir refuses, he can do what he wants’.Footnote 91 Of course the defendant claimed Ffye had done this, and also pointed out that it was ‘well known’ that the rightful heirs ‘were not very wealthy and could not afford to maintain the old woman’ and by implication would simply not have been in a position to enter into the retirement contract.Footnote 92 The duke agreed and decided in favour of the defendant: Ffye was within her rights when she decided to spend her old age in the care of her niece rather than her sisters.

7. Conclusion

Our study shows how the elderly could resolve the dilemma of ‘poor parents, rich children’. By using their property in a strategic way, they ensured they would receive help from the younger generation during old age, without giving up agency. Wills and retirement contracts served as the proverbial baited stick that kept the reward dangling before the noses of the caregivers and encouraged them to provide eldercare. Since testaments could easily be adjusted if the younger generation failed to provide the agreed-upon care, the promise of an inheritance put the elderly in a position of power. The same is true of the conditional transfers of property found in retirement contracts, which could be revoked after an appeal to the local law court. Both types of contracts provided the elderly with agency because they allowed for negotiating legally binding arrangements with more remote relatives and non-relatives, such as live-in servants and third parties. The option to spend one's final years with non-relatives was obviously important for those without family nearby – likely a sizeable portion of the urban population. Yet, it may also have been helpful for those elderly who did have access to a family network because the possibility to seek eldercare with third parties improved their bargaining position vis-à-vis their next of kin. Sons and daughters had to anticipate losing part of the inheritance if they were not as forthcoming as their parents desired. Contracts not only allowed the elderly to decide who to spend their old age with, but also to stipulate what would happen in future scenarios, such as when they were cared for by a couple and one of the spouses would die. Ending up in the care of a widowed in-law was not always deemed the best of prospects, and quite a few seniors maintained the right to have the contract terminated in such a scenario and look for another type of eldercare. Seniors also took charge of their final years in terms of material demands. Some negotiated a certain standard of living by stipulating that they expected to receive foodstuffs, drink, clothing and certain services. Others demanded food and lodging fitting with the seniors’ social status. This suggests that the elderly were concerned with maintaining their social position during old age and that they wanted to prevent a painful tumble down the rungs of the social ladder. Perhaps the best way to prevent both relative impoverishment during old age, as well as absolute impoverishment, was to retain agency by employing the strategies that have been highlighted in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare none.