Article contents

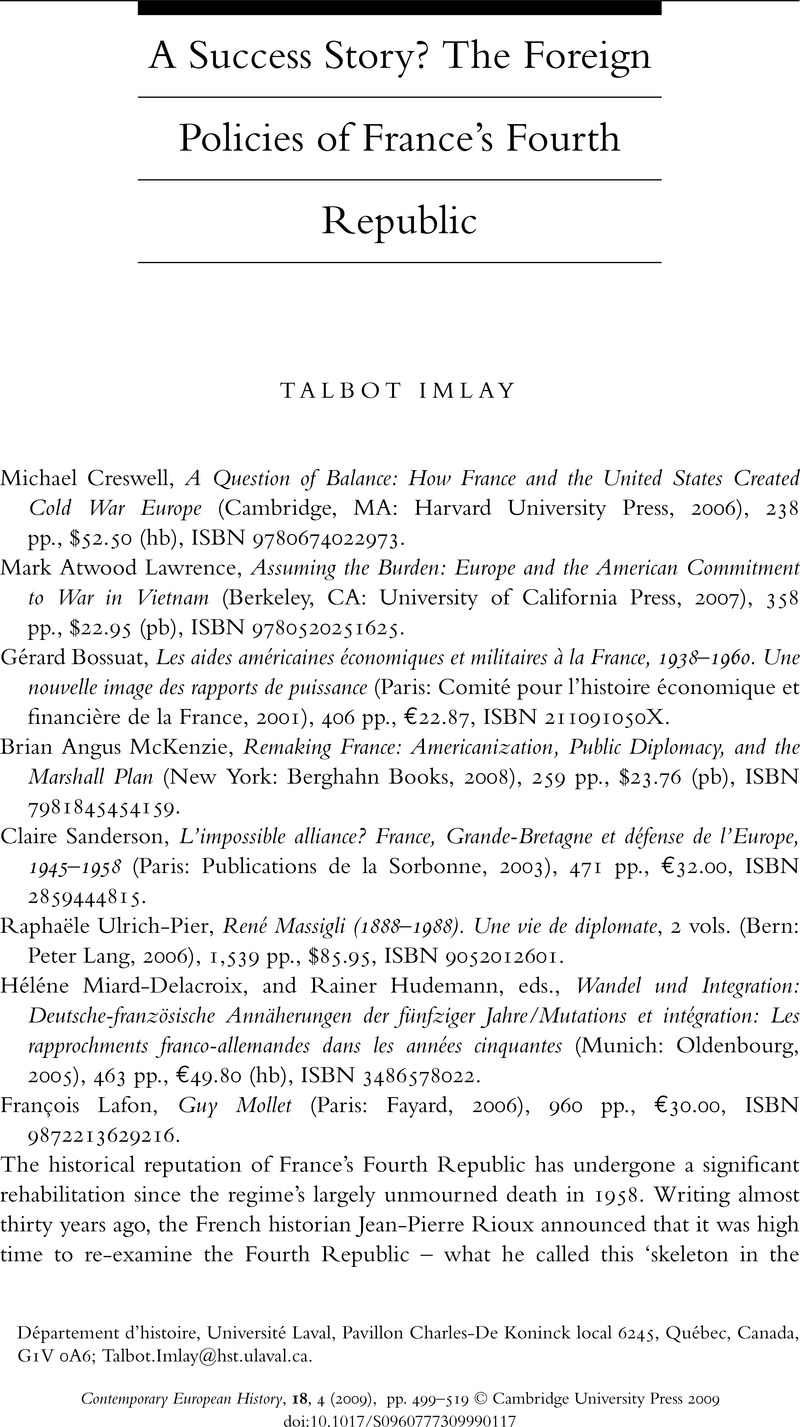

A Success Story? The Foreign Policies of France's Fourth Republic

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 September 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 2009

References

1 Rioux, Jean-Pierre, The Fourth Republic 1944–1958 (Cambridge, 1989), xiGoogle Scholar. The original French version appeared in 1980.

2 This more favourable view is perhaps most evident in the economic realm. For example, see Lynch, Frances M. B., France and the International Economy: From Vichy to the Treaty of Rome (London, 1997)Google Scholar; Margairaz, Michel, L'Etat, les finances et l'économie. Histoire d'une conversion 1932–1952, 2 vols., II (Paris, 1991)Google Scholar; and Kuisel, Richard, Capitalism and the State in Modern France: Renovation and Economic Management in the Twentieth Century (New York, 1981), 157–271Google Scholar. But this view is also apparent in other realms. Thus, for example, Todd Shepard has recently argued that Fourth Republic governments introduced innovative and promising policies concerning French citizenship towards the end of the Algerian war – policies that quickly disappeared at the end of the war. See his The Invention of Decolonization: The Algerian War and the Remaking of France (Ithaca, NY, 2006), 19–54.

3 Hitchcock, William, France Restored: Cold War Diplomacy and the Quest for Leadership in Europe, 1944–1954 (Chapel Hill, NC, 1998), 208Google Scholar; Hüser, Dietmar, Frankreichs ‘doppelte Deutschlandpolitik’. Dynamik aus der Defensive – Planen, Entscheiden, Umsetzen in gesellschaftlichen und wirtschaftlichen, innen- und auβenpolitischen Krisenzeiten 1944–1950 (Berlin, 1996)Google Scholar.

4 See Wall, Irwin, ‘France in the Cold War’, Journal of European Studies, 38, 2 (2008), 121–39CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and Wall, The United States and the Making of Postwar France, 1945–1954 (Cambridge, 1991). And from a different perspective, Thomas, Martin, ‘France's North African Crisis, 1945–1955: Cold War and Colonial Imperatives’, History, 92 (2007), 207–34CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

5 See his review of Michael Creswell's A Question of Balance in H-France Review, 7, 148 (2007), available at www.h-france.net/vol7reviews/lawrence2.html.

6 For the standard view, see Grosser, Alfred, Affaires extérieures. La politique de la France 1944–1989 (Paris: Flammarion, 1989), 106–112Google Scholar.

7 Other studies either appeared before the opening of most national archives or adopt a limited perspective. See Ruane, Kevin, The Rise and Fall of the European Defence Community: Anglo-American Relations and the Crisis of European Defence, 1950–55 (Basingstoke, 2000)CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and Fursdon, Edward, The European Defence Community: A History (London, 1980)CrossRefGoogle Scholar. But see also Trachtenberg, Marc, A Constructed Peace: The Making of the European Settlement, 1945–1963 (Princeton, NJ, 1999), 103–25Google Scholar; and Volkmann, Hans-Erich and Schwengler, Walter, eds., Die Europäische Verteidigungsgmeinschaft. Stand und Probleme der Forschung (Boppard am Rhein, 1985)Google Scholar.

8 Creswell builds on the work of Philippe Vial and Pierre Guillen. For Vial, see ‘Le militaire et le politique: le Maréchal Juin et le Général Ely face à la CED (1948–1954)’, Revue historique des armées, 2 (2002), 33–46. For Guillen, see ‘Les chefs militaires français, le réarmement de l'Allemagne et la CED (1950–1954)’, Revue d'histoire de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale et des conflits contemporains, 33 (1983), 3–33. Also see David Mark Thompson, ‘Delusions of Grandeur: French Global Ambitions and the Problem of a Revival of Military Power, 1950–1954’, Ph.D. thesis, University of Toronto, 2007, which is based on extensive use of French military archives.

9 Lappenküper, Ulrich, Die deutsch-französischen Beziehungen 1949–1963: Von der ‘Erbfeindschaft’ zur ‘Entente élémentaire’, 2 vols. (Munich, 2001), ICrossRefGoogle Scholar; Maelstaf, Geneviève, Que faire de l'Allemagne? Les responsables français, le statut international de l'Allemagne et le problème de l'unité allemande (1945–1955) (Paris, 1999)Google Scholar; and Hitchcock, France Restored.

10 A point stressed by William I. Hitchcock in his ‘Response to France and the German Question, 1944–1955, by Michael Creswell and Mark Trachtenberg’, Journal of Cold War Studies, 3 (2003), 34–5.

11 This is a fundamental point of Hüser's study, Frankreichs ‘doppelte Deutschlandpolitik’. As Pierre Guillen shows, Mendès-France made effective use of this argument in the inter-allied negotiations following the EDC's demise. See his ‘Frankreich und die NATO-Integration der Bundesrepublik’, in Ludolf Herbst et al., eds., Vom Marshallplan zur EWG: Die Eingliederung der Bundesrepublik Deutschland in die westliche Welt (Munich, 1990), 427–45.

12 For Bidault's comments, see ‘Genfer Kreis, 22.12.1948, Protokol Koutzine’, reproduced in Gehler, Michael and Kaiser, Wolfram, eds., Transnationale Parteienkooperation der europäischen Christdemokraten: Dokumente 1945–1965 (Munich, 2004), 151–2Google Scholar. For Bidault's early post-war German policy, see the nuanced assessment of Reinhard Schreiner, Bidault, der MRP und die französische Deutschlandpolitik, 1944–1948 (Frankfurt a. M., 1985), especially 169–70.

13 When the National Assembly approved the Pleven Plan in October 1950, it attached a resolution opposing the creation of a German army and a Defence Ministry. See Thompson, ‘Delusions of Grandeur’, 127.

14 For Mollet, see Archives d'histoire contemporaine, Sciences Politiques, Paris, Groupe socialiste parlementaire, GS 6, 16 December 1954. Significantly, the result of the parliamentary vote on the accords was widely seen as a defeat for the government of Pierre Mendès-France since a sizeable majority of deputies refused to endorse the accords, either voting against or abstaining. See Bariéty, Jacques, ‘Frankreich und das Scheitern der EVG’, in Steininger, Rolf et al. , eds., Die doppelte Eindämung: Europäische Sicherheit und deutsche Frage in den Fünfzigern (Munich, 1993), 123–6Google Scholar.

15 Wall, Irwin M., France, the United States, and the Algerian War (Berkeley, CA, 2001)CrossRefGoogle Scholar. As Matthew Connelly has shown, the Algerian FLN enjoyed considerable success within the United Nations in framing the war as a North–South rather than East–West struggle – a success that no doubt contributed to undermining support for the war within France. See his A Diplomatic Revolution: Algeria's Fight for Independence and the Origins of the Post-Cold War Era (Oxford, 2002).

16 For figures on US aid and on France's burden, see Tertrais, Hugues, La piastre et le fusil. Le coût de la guerre d'Indochine 1945–1954 (Paris, 2002), 24Google Scholar, 186, 190, 230, 260, 270, 354, 359. It was only in 1953 that US financial aid surpassed French spending on the war. For the increased US physical presence in Indo-China, see Statler, Kathryn C., Replacing France: The Origins of American Intervention in Vietnam (Lexington, KY, 2007), 15–95CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

17 On France and the EPC see Kim, Seung-Ryol, ‘Jean Monnet, Guy Mollet und das Projekt der Europäischen Politischen Germeinschaft (EPG)’, Francia 29 (2002), 63–98Google Scholar.

18 The same argument can be made for the Schuman Plan.

19 For the earlier study, see Bossuat, La France, l'aide américaine et la construction européenne, 1944–1954, 2 vols. (Paris, 1992).

20 It appears that the British were initially interested in an Anglo-French colonial partnership. See Deighton, Anne, ‘Entente Neo-Coloniale?: Ernest Bevin and the Proposals for an Anglo-French Third World Power, 1945–1949’, Diplomacy and Statecraft, 17 (2006), 835–52CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

21 But see Lacroix-Riz, Annie, Le choix de Marianne: les relations franco-américaines, 1944–1948 (Paris, 1985)Google Scholar.

22 For a less categorical assessment see Vial, Philippe, ‘L'aide américaine au réarmament français (1948–1956)’, in Vaïsse, Maurice, Mélandri, Pierre and Bozo, Frédéric, eds., La France et l'OTAN 1949–1966 (Brussels, 1996), 169–87Google Scholar.

23 For example, see the differing views of Irwin Wall and Matthew Connelly on the US role in the Fourth Republic's fall in Wall, France, the United States, and the Algerian War, 134–56; and Connelly, ‘The French-American Conflict over North Africa and the Fall of the Fourth Republic’, Outre-Mers, 84 (1997), 9–27.

24 Kuisel, Richard, Seducing the French: The Dilemma of Americanization (Berkeley, CA, 1993), esp. 70–102Google Scholar; Kuisel, ‘“L'American Way of Life” et les missions françaises de productivité’, Vingtième Siècle 17 (1988), 21–38; and Hogan, Michael, The Marshall Plan: America, Britain, and the Reconstruction of Western Europe, 1947–1952 (Cambridge, 1987)CrossRefGoogle Scholar. McKenzie's concentration on government efforts also distinguishes his study from that of Victoria de Grazia, which explores the role of American businesses in spreading a capitalist-consumer society in western Europe after the First World War. See her Irresistible Empire: America's Advance through 20th Century Europe (Cambridge, MA, 2005).

25 Pells, Richard, Not Like Us: How Europeans have Loved, Hated, and Transformed American Culture since World War II (New York, 1997)Google Scholar; and Kroes, Rob, ‘American Empire and Cultural Imperialism: A View from the Receiving End’, in Bender, Thomas, ed., Rethinking American History in a Global Age (Berkeley, CA, 2002), 295–313CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

26 Here, McKenzie differs from Kristin Ross, who argues that after 1945 the French embraced the American consumerist vision – a vision that proved to be incompatible with aspects of French foreign and colonial policy, especially the ‘dirty war’, in Algeria. See Ross, Fast Cars, Clean Bodies: Decolonization and the Reordering of French Culture (Cambridge, MA, 1995).

27 Roger, L'ennemi américain: généalogie de l'antiaméricanisme français (Paris, 2002).

28 See Ikenberry, G. John, After Victory: Institutions, Strategic Restraint, and the Rebuilding of Order after Major Wars (Princeton, NJ, 2001), 163–214Google Scholar; and Keohane, Robert, After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy (Princeton, NJ, 1984), 31–46, 135–82Google Scholar.

29 In an influential article, Geir Lundestad went so far as to argue that west European countries after 1945 invited the United States to impose its empire on them. Although this thesis usefully highlights differences between the way in which the Americans and the Soviets exercised influence within their respective alliance blocs, it arguably exaggerates the choices available to west European governments. See Lundestad, ‘Empire by Invitation? The United States and Western Europe’, Journal of Peace Research, 23 (1986), 263–77.

30 For a similar demonstration see Dockrill, Saki, British Policy for West European Rearmament, 1950–1955 (Cambridge, 1991)Google Scholar; also see Dockrill, ‘The Evolution of British Policy towards a European Army 1950–54’, Journal of Strategic Studies, 12 (1989), 38–63.

31 On British satisfaction with the Paris accords, see Saki Dockrill, ‘Grossbritannien und die Wiederbewaffnung Deutschlands 1950–1955’, in Steininger et al., Die doppelte Eindämung, 63–74.

32 This is not to overlook the very real financial burden that troops on the continent represented for the British. On this point, see Zimmermann, Hubert, ‘The Sour Fruits of Victory: Sterling and Security in Anglo-German Relations during the 1950s and 1960s’, Contemporary European History, 9 (2000), 225–43CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

33 Soutou, ‘La politique nucléaire de Pierre Mendès-France’, Relations Internationales, 59 (1989), 317–30; and Soutou, L'Alliance incertaine: les rapports politico-stratégiques franco-allemands, 1954–1996 (Paris, 1996), 55–148. Jacques Bariéty, by contrast, suggests that the French sought an independent nuclear force that would ensure their superiority within NATO over Germany, since the Paris accords prohibited the latter from possessing nuclear weapons among others. See Bariéty, ‘Frankreich und das Scheitern der EVG’, 108–26. For good introductions to the history of France's nuclear program see Mongin, Dominique, La Bombe atomiqe française, 1945–1958 (Brussels, 1997)Google Scholar; and Vaïsse, Maurice, ed., La France et l'atome. Éudes d'histoire nucléaire (Brussels, 1994)Google Scholar.

34 On this subject see the suggestive article by O'Driscoll, Mervyn, ‘Missing the Nuclear Boat?: British Policy and French Military Nuclear Ambitions during the EURATOM Foundation Negotiations, 1955–56’, Diplomacy & Statecraft, 9 (1998), 135–62CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

35 It is also worth noting that French officials never completely abandoned hopes of balancing between Moscow and Washington. On this point see Soutou, Georges-Henri, ‘La perception du problème soviétique par le Quai d'Orsay entre 1945 et 1949’, Revue d'Allemagne, 30 (1998), 273–84Google Scholar; and Soutou, ‘France and the Cold War, 1944–63’, Diplomacy & Statecraft, 12 (2001), 43–44.

36 On divisions within the Quai d'Orsay see also Ulrich-Pier, Raphaële, ‘Antifédéralistes et fédéralistes: le Quai d'Orsay face à la construction européenne’, in Catala, Michel, ed., Histoire de la construction européenne: cinquante ans après la déclaration Schuman (Nantes, 2001), 103–18Google Scholar. See also Maelstaf, Que faire de l'Allemagne?, and Bossuat, Gérard, ‘The French Administrative Elite and the Unification of Western Europe, 1947–58’, in Deighton, Anne, ed., Building Postwar Europe: National Decision-Makers and European Institutions, 1948–63 (London, 1995), 21–37CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

37 On Mendès-France see Girault, René, ed., Pierre Mendès-France et le rôle de la France dans le monde (Grenoble, 1991)Google Scholar; and Allain, Jean-Claude et al. , Histoire de la diplomatie française II. De 1815 à nos jours (Paris, 2007), 397–400Google Scholar.

38 Hudemann began by studying France's occupation zone in Germany. See his Sozialpolitik im deutschen Sudwest zwischen Tradition und Neuordnung, 1945–1953: Sozialversicherung und Kriegsopferversorgung im Rahmen französischer Besatzungspolitik (Mainz, 1988); and ‘L'occupation française après 1945 et les relations franco-allemandes’, Vingtième Siècle, 55 (1997), 58–68. For a good example of earlier work, see Kiersch, Gerhard, ‘Die französische Deutschlandpolitik 1945–1949’, in Scharf, Claus and Schröder, Hans-Jürgen, eds., Politische und ökonimische Stabilisierung Westedeutschlands 1945–1949. Fünf Beiträge zur Deutschlandpolitik der westlichen Allierten (Wiesbaden, 1977), 61–76Google Scholar.

39 While Lappenküper's emphasis on the pursuit of national interests reflects recent trends in the scholarship on the origins of European unity, it arguably gives a one-sided picture of the relationship between policy methods and aims. It is not simply the case that aims determined methods; novel methods can also help to reshape aims. For helpful discussions of the historiography on European unity, see Kaiser, Wolfram, ‘From State to Society? The Historiography of European Integration’, in Cini, Michelle and Bourne, Angela K., eds., Palgrave Advances in European Union Studies (London, 2006), 190–208CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and Loth, Wilfried, ‘Beiträge der Gesichtswissenschaft zur Deutung der europäischen Integration’, in Loth, and Wessels, Wolfgang, eds., Theorien europäischer Integration (Opladen, 2001), 87–106CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

40 In his chapter on the role of economic integration on French and German economic growth, André Steiner remarks that more research is needed before conclusions can be confidently drawn. See his ‘Realwirtschaftliche Folgen des westeuropäischen Integrationsprozesses von den fünfziger Jahren bis zur Mitte der siebziger Jahre. Fragen und erste Ergebnisse’, 179–91, and especially 184. On Franco-German economic relations more generally, see Lefèvre, Sylvie, Les relations économiques franco-allemandes de 1945 à 1955: De l'occupation à al coopération (Paris, 1998)CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and Wilkens, Andreas, ed., Die deutsche-französische Wirtschaftsbeziehungen 1945–1960 (Sigmaringen, 1997)Google Scholar.

41 Lefebvre, Denis, Guy Mollet. Le mal aimé (Paris, 1992)Google Scholar. See also Ménager, Bernard, ed., Guy Mollet: un camarade en République (Lille, 1987)Google Scholar.

42 For the SFIO and Algeria, see also Gilles Morin, ‘De l'opposition socialiste à la Guerre d'Algérie au Parti Socialiste autonome (1954–1960). Un courant socialiste de la S.F.I.O. au PSU’, thesis, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, 1990–1; and Etienne Maquin, Le Parti socialiste et la guerre en Algérie: la fin de la vieille maison, 1954–1958 (Paris, 1990).

43 In an important early article, Tony Smith argued that the entire French political class was the prisoner of a ‘colonial consensus’. See his ‘The French Colonial Consensus and People's War, 1946–58’, Journal of Contemporary History, 9 (1974), 217–47. For a similar argument that focuses on the MRP, see Thomas, Martin, ‘The Colonial Policies of the Mouvement républicain populaire, 1944–1954: From Reform to Reaction’, English Historical Review 118 (2003), 380–411CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

44 Bossuat, ‘French Administrative Elite’, 28–29.

45 For Fourth Republic figures see for example Winock, Michel, Pierre Mendès-France (Paris, 2005)Google Scholar; Méchoulan, Eric, Jules Moch: un socialiste dérangeant (Brussels, 1999)Google Scholar; de Tarr, Francis, Henri Queuille et son temps (1884–1970) (Paris, 1995)Google Scholar; and Poidevin, Raymond, Robert Schuman: homme d'état, 1886–1963 (Paris, 1986)Google Scholar. For earlier attitudes towards political biography see the discussion in Pillorget, René, ‘Die Biographie als historiographische Gattung: Ihre heutige Lage in Frankreich’, Historisches Jahrbuch, 99 (1979), 327–54Google Scholar.

46 Richard Vinen has argued that domestic politics in general has been a neglected element of scholarship on the Fourth Republic. See his Bourgeois Politics in France, 1945–1951 (Cambridge, 1995), 12–20. For valuable efforts to place Fourth Republic colonial policies in a domestic political context see Turpin, Frédéric, De Gaulle, les gaullistes et l'Indochine: 1940–1956 (Paris, 2005)Google Scholar; and Thomas, ‘Colonial Policies’.

- 2

- Cited by