Introduction

‘The financial centers of the world will no longer be limited to New York, London, Zurich and Paris. New centers of economic power would rise in the Non-aligned and the Third World’, declared Sri Lankan Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike at the 1976 Colombo Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement.Footnote 1 Two years earlier, at the historic Sixth Special Session of the United Nations General Assembly that resulted in the ‘Declaration on the Establishment of a New International Economic Order’, Henry Kissinger told the UN General Assembly that ‘the notion of the northern rich and the southern poor has been shattered’ in a speech entitled ‘The Challenge of Interdependence’.Footnote 2 Indeed, the aftermath of the first oil shock not only put on the map of the global economy previously little known capitals and actors from across the ‘Third World’, it also unleashed an unprecedented sense of triumphalism and confidence among the countries of the Global South, most of which were members of the Non-Aligned Movement.Footnote 3 However, despite the newly found sense of geo-political dignity, it was the developing countries outside of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) that were most severely affected by the economic upheavals of the 1970s. Although 1974 was termed ‘the year of the Third World’ as ‘the highpoint of developing country ambitions to restructure international economic relations’,Footnote 4 non-oil producing countries suffered grave consequences in the aftermath of what was termed ‘one of the seventies’ seismic events’.Footnote 5 Yet, a sense of triumphalism underpinned official discourse among the non-aligned throughout the 1970s. As it was astutely observed, ‘OPEC's success provided an uplifting of morale, possibly unrealistic in light of subsequent events, even to non-member developing countries … despite the near bankruptcy of some resulting from the quadrupled oil prices’.Footnote 6

How does a geopolitical and a global political economy lens enrich our understanding of the relations and circulations between Eastern Europe and the Middle East in a longue durée perspective? Situating the relationship between South Eastern Europe and the Middle East within a broader framework of international economic relations and economic decolonisation provides us with a venue for approaching and analysing the Non-Aligned Movement differently, more specifically through the debates on national and economic sovereignty and the role played by primary commodities and petroleum in particular. Furthermore, by examining these relationships, the article seeks to capture the competing senses of triumphalism and dread that marked the shift from decolonisation to neo-liberal globalisation in the history of the international political economy. The article provides a broader overview of the importance of the geopolitics of oil in the non-aligned world and seeks to demonstrate the complex interplay between political and economic emancipation and the role of the oil crises in the eventual unravelling of non-aligned solidarity. It explores how imperial pathways and pre-existing cultural, religious and historical ties significantly shaped relations within the non-aligned world, in this case between the Balkans and the Middle East. More specifically, the article analyses Yugoslavia's relations with the Middle East and probes the origins of this alliance which were far from stable – from the first encounters with Gamal Abdel Nasser's Egypt and the postulates of Arab socialism, to the narrowing down of relations to more or less exclusive economic cooperation with Middle Eastern non-aligned partners such as Kuwait in the 1970s and 1980s. Crucially, a project like the Adria Pipeline that foresaw the supply of Arab oil to areas which had traditionally relied on Soviet energy foreshadowed the emergence of new relations of dependence between South Eastern Europe and the Middle East.

Indeed, what the crisis revealed was an interconnected world where energy interdependence was a major pillar of the globalising world economy of transnationalised capitalism. A prominent topic in academic debate and political discourse at the time,Footnote 7 ‘interdependence’, alongside ‘collective self-reliance’, was also frequently used in non-aligned discourse and policy. Hence, the article also seeks to analyse how this new, acute sense of interdependence as both opportunity and threat was understood and translated in the non-aligned world. The project of economic emancipation that the rich non-aligned oil producers in the Middle East made possible elicited both a sense of triumph and economic downfall, but it also paved the way for a global debate on other primary commodities and terms of trade. The redefinition of international economic relations, sovereignty over natural resources and eliminating the gap between developing and developed nations became the core shared goals that would be ultimately enshrined in the framework for a ‘New International Economic Order’ (NIEO) in the mid-1970s.Footnote 8 Moreover, there was a shared sense that the NIEO was a culmination of initiatives and efforts that had begun in the 1940s,Footnote 9 or, that what later evolved into the NIEO was ‘simply a collection of the ideas which accumulated over years’.Footnote 10

This article seeks to contribute to the existing scholarship on the international history of decolonisation and the 1970s and to fill a historiographic gap by embedding the non-oil producing countries within the Non-Aligned Movement – such as Yugoslavia – in what has been termed the ‘economic culture of decolonization’.Footnote 11 This new original research has so far elucidated the agency and role of ‘anti-colonial elites’, foregrounding oil elites from the Global South, and showed how OPEC assumed a role that went far beyond the sphere of oil politics.Footnote 12 De-centring Western accounts of the history of energy and the Cold War, other authors have positioned the Soviet Union as a protagonist, rather than just a rival, in Cold War global politics and international relations.Footnote 13 This article seeks to go beyond and embed historical actors and events which were part of the same international organisations and networks, yet are usually left out of these accounts. Despite being outside of the OPEC realm, they played a central role within the debates about international economic relations, energy and development.

The article draws upon multiple Yugoslav and international archives, as well as a range of published primary material. Structured around three major themes – anti-imperialist/revolutionary solidarity, self-reliant development and energy interdependence – it begins by analysing the historical links between Yugoslavia and the Middle East, by focussing on Egyptian–Yugoslav relations, the tenets of Arab and Yugoslav socialism and the consensus over economic development that defined their early encounters within the Non-Aligned Movement. The second part embeds the Adria Pipeline – a major trans-Bloc and North–South project, constructed between 1974 and 1979 – in the doctrine of self-reliant development. A pragmatic response to energy interdependence in a globalising world, it was also an exercise in Cold War developmental multilateralism and in what in non-aligned discourse was referred to as ‘collective self-reliance’. The Adria Pipeline, recognised today as a European Union strategic oil pipeline, is also one of the rare projects that survived the demise of Yugoslav socialism and the end of the Cold War.Footnote 14 The last section engages more closely with the geopolitics of oil, the rise in energy interdependence in the 1970s and the emergence of new hierarchies of power in the non-aligned world. By the beginning of the 1980s the high hopes surrounding economic emancipation, although not lost, had dissipated, and the sense of triumph, hope and confidence had given way to discontent with OPEC policies and increasingly asymmetric relations.

The Non-Aligned Movement and the Middle East

In a 1956 publication entitled The Middle East on the World Stage, three Yugoslav authors offered a detailed historical, political and economic overview of each of the Middle Eastern countries. ‘Our country is naturally directed towards a robust trade exchange with the countries of the Middle East by virtue of its geographical positioning and the structure of our production’, they concluded.Footnote 15 However, because of its geographical proximity and common imperial history, Egypt was traditionally the closest Middle Eastern country with which the states of the Balkan Peninsula and the future Yugoslav federation had meaningful contacts and exchange. Early observations and studies of the region noted the long historical connections between the Yugoslav lands and Egypt, ever since the thirteenth century, when sailors from Dalmatia and Dubrovnik traded goods from as far as China, India, Yemen and the Arab Peninsula.Footnote 16 The Serbian Kingdom opened its first consulate in Cairo in 1907Footnote 17 and, most notably for the Yugoslav post-war elite, Egypt was the point of contact with the Allies for the Yugoslav military mission of the anti-fascist liberation movement in 1943–4.Footnote 18 However, it was not until the overthrowing of the Egyptian monarchy in 1952 that the relations between the two countries intensified, in particular after the signing in the summer of 1953 of the first bilateral agreement on trade and economic cooperation. Nasser's own political views on social justice and equality,Footnote 19 the inseparable nature of a political and a social revolution, including Egypt's large-scale land reform in the 1950s and its nationalisation program,Footnote 20 struck chords with the Yugoslav leadership, who shared similar views on the nature of the Yugoslav revolution. Indeed, in both countries, visions of nation building and foreign policy were intertwined and understandings of social justice at home were projected onto an international plane: an anti-colonial ethos underpinned arguments about economic decolonisation, interdependence and the right of small and medium-sized states to have a voice in the shaping of the global economic order and an equal standing in international affairs. Yugoslav observers at the Bandung conference in 1955 took note of Nasser's speech and reported back, emphasising what they recognised as important shared values and principles: his support for the United Nations, his stance against bloc divisions and the bloc politics of the great powers, his demand for small and medium-sized countries to play an independent and constructive role in international relations, his condemnation of the ongoing discrimination in South Africa and colonialism in North Africa, his view that every country had the right to choose its own political and economic system and his support for Palestine.Footnote 21 In addition to a consensus over the politics of nationalisation and sovereignty over natural resources, Yugoslavia's unwavering support for the Palestinian cause was what further sustained the bond between Yugoslavia and the Middle East. This was a political and a diplomatic commitment that persisted throughout the Cold War but also preceded the non-aligned era. Yugoslavia was a member of the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) that was established in 1947 and consisted of eleven ‘neutral’ countries, deliberately excluding participation by any of the five Security Council members. The Yugoslavs opposed the majority proposal of the committee for partition into two independent states with an economic union and instead pioneered the minority proposal for a plan for a federal union with Jerusalem as the capital.Footnote 22

When Nasser visited Belgrade in 1956 he underlined the ‘joint experience of Yugoslavia and Egypt of liberation and independence’ and the shared belief that world peace could be achieved only by recognising each country's right to formulate its own foreign policy according to its own circumstances and conditions, without the interference or control by any other country.Footnote 23 The common doctrine of positive neutrality (and later that of non-alignment) was born in the context of Bandung and the Suez crisis. Yugoslavia played a particularly prominent role in the latter as a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council in 1956, as well as one of the countries with the biggest contingents in the UN Emergency Force (UNEF I) peacekeeping operation between 1956 and 1967.Footnote 24 In that context, with a looming ‘danger that the Cold War turns into a hot war’,Footnote 25 in July 1956 Nasser, Tito and Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru met on the Croatian island of Brijuni and signed a declaration which paved the way for the official inauguration of the Non-Aligned Movement five years later at the Belgrade Summit.

In addition, cultural and historical links and perceived historical commonalities also determined Yugoslavia's alliances with Egypt and the Middle East. Yugoslavia's Ottoman heritage and the largest European Muslim population were a crucial link: during his 1956 visit to Yugoslavia Nasser visited a mosque and was introduced to local Islamic religious leaders.Footnote 26 In addition to the personal friendship they developed, Josip Broz and Nasser shared one crucial trait in their understanding of the contemporary post-colonial, Cold War world: both of them managed to secure not only an independence to choose between East and West, as it was astutely remarked of Nasser, ‘but also the special grace to choose both’.Footnote 27 During the same 1956 visit to Yugoslavia, Nasser was also taken to the Museum of Young Bosnia in Sarajevo which recounted the story of the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914. Yugoslavia's anti-colonial credentials were thus tailored and fused with its Second World War liberation struggle to create a relatable common political and cultural ground that could turn a European country into a credible member of the largely post-colonial and non-European Non-Aligned Movement.

At the Belgrade Summit in 1961 a considerable number of Middle Eastern states, including Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Lebanon and the United Arab Republic, were among the founding members of the Non-Aligned Movement. Over the following decades, all of the other Middle Eastern countries (with the exception of Turkey and Israel), including the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), joined the movement. However, political tropes of sovereignty and liberation were soon replaced by a vocabulary and initiatives from the realm of economics. This ushered in a new era of polycentric multilateral development diplomacy, in which newly independent countries and the Non-Aligned Movement played a central role. An economic conference of non-aligned states followed quickly after the 1961 founding summit in Belgrade and took place in Cairo the following year. Following preliminary discussions between Tito and Nasser, the Yugoslav and the Egyptian foreign ministers Koča Popović and Mahmoud Fawzi agreed on the organisation of a ‘Conference on the Problems of Economic Development’.Footnote 28 The Egyptian-Yugoslav initiative caught the attention of Raúl Prebisch, the future Secretary-General of the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), who attended the Cairo conference in the capacity of a special envoy of UN Secretary-General U Thant. The conference proved to be the stepping stone for a number of other initiatives – not least the Group of 77 developing countries (G-77), UNCTAD, the UN Centre for Transnational Corporations (UNCTC) and the Common Fund for Commodities (CFC), all of which redefined the role of the United Nations and the South in the realm of international economic relations. As Mazower has observed, the solidarity of the G-77 both ‘impressed and disturbed Western diplomats’.Footnote 29

The debates on commodities and terms of trade within the G-77 and UNCTAD in the 1960s and the 1970s significantly influenced and overlapped with the mission the Non-Aligned Movement had set for itself within its economic declarations. Without fundamental structural reform of the world economy, trade would continue to benefit nations that were exporters of manufactures, harming primary producers’ terms of trade.Footnote 30 Indeed, permanent sovereignty and unequal exchange became standard arguments articulated and shared across Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Middle East.Footnote 31 Although Yugoslavia does not usually feature in these histories, Yugoslav diplomats and economists partook in these intellectual exchanges within the United Nations – Yugoslavia was one of the select group of eight delegations that Raúl Prebisch invited for a ten-day marathon of private negotiations before the convening of UNCTAD, and the Yugoslav/Slovenian economist and career diplomat Janez Stanovnik, who later headed the UN Economic Commission for Europe from 1967 to 1983, worked as Prebisch's personal assistant and advisor.Footnote 32 The line of reasoning, which could be best described as a syncretic revolutionary worldview, posited the restructuring of the global economy and trade as fundamental to maintaining world peace. In the words of the Yugoslav president, ‘Europe cannot exist as an island of tranquillity and well-being in a sea of world instability and poverty’.Footnote 33

In the mid-1960s this worldview reached into the world of oil politics. As it was stated at a conference dedicated to petroleum at the Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts in 1966, ‘universal cooperation in the world economy on the basis of equality is fundamental for the achievement of permanent peace in the world’.Footnote 34 The conference was convened in view of oil's importance as ‘a political instrument in the hands of the Arab countries’.Footnote 35 The conclusions proved rather prescient in designating petroleum ‘not only a commodity, but also a strategic raw material on which the Arab countries can rely in the future for making profit and playing an important role internationally’.Footnote 36 So when the wave of nationalisations began in the aftermath of the 1973/74 OPEC price increases, and when in December 1975 Iraq finalised the process by taking over the remaining holdings of British Petroleum (BP) and Shell,Footnote 37 Yugoslavia could identify with the battle against ‘oil imperialism’, as the Yugoslav elite could relate to these events through personal histories of revolutionary struggle. ‘We are no one's colony, where foreign capitalists can freely implement their dark scenarios’,Footnote 38 asserted in 1940 an anonymous local activist with regard to the Yugoslav oil industry being in American and British ownership and the exploration of oil fields being controlled by German capital. In 1921 Shell founded the Anglo-Yugoslav Petroleum Joint Stock Company (renamed in 1936 Yugoslav Shell) and opened a refinery near the Croatian town of Sisak in 1927. The Sisak refinery would become one of the major hubs on the Adria Oil Pipeline in the 1970s. In the interwar period foreign capital was also present in the mining sector and, therefore, issues of exploitation and ownership, labour rights and labour unrest were fundamental for the interwar Yugoslav communist movement which was rooted in workers’ unions throughout the country. The fifteen-day strike of the Sisak refinery workers in 1936 was one of the most significant workers’ strikes in Croatia. After the end of the Second World War Yugoslavia nationalised all of the assets owned by Yugoslav Shell. When the main oil producing countries in the Global South and the Non-Aligned Movement launched a similar wave of nationalisations in the 1960s and 1970s, the Yugoslav revolutionary elite could easily identify with the new transnational politics of economic decolonisaiton and use it to forge political and economic bonds with the new Middle East.

It is important to note that, in general, cultural cooperation between Yugoslavia and the Middle East lagged behind economic and technological and scientific exchange. In the context of the 1980s’ economic crisis this trend became even more prominent as economic cooperation took precedence over all other forms. For instance, in 1988, at a meeting at the Federal Council for International Scientific, Educational-Cultural and Technical Cooperation, the cultural attaché at the Iraqi Embassy in Belgrade complained that Yugoslavia was not fulfilling its obligations from the bilateral treaties for awarding scholarships to Iraqi citizens to study in Yugoslavia and threatened to withdraw from the bilateral programme for educational and cultural cooperation. The Yugoslav authorities underlined the financial difficulties their country was facing and, instead, asked for more information on the recruitment for foreign academic staff at Mosul University. This signalled a reversal of roles that took place over several decades, with Yugoslavia's non-aligned Middle Eastern partners overtaking her economically and turning her into the dependent ally. Arguably, only less developed Middle Eastern countries such as the Arab Republic of Yemen could still look up to Yugoslavia and seek assistance and cooperation: from specialists in urban planning for the cities of Sanaa and Hodeida, to requests about technical maintenance of Yemeni planes, the Yemeni Ambassador in Rome, Abdullah Aldhabbi, complained to the Yugoslav vice-president of the Council for International Cooperation that Yemen's oil-rich neighbours had decreased the aid funding for his country only because there was a small drop in the price of oil.Footnote 39 At the same time, particularly in the second half of the 1980s, forced to deal with rising inflation and balance of payments difficulties, as will be discussed below, Yugoslavia started to look for more lucrative arms trade deals with oil-rich partners and sought to further enhance its relationships with Western Europe.

The Doctrine of Self-Reliant Development and the Trans-Bloc Pipeline

An important common trend that united the main Cold War adversaries and countries across the ideological divide was increased energy consumption. Between 1950 and 1972 total world energy consumption increased 179 per cent, much faster than population growth. Oil accounted for much of this increase, rising from 29 per cent of world energy consumption in 1950 to 46 per cent in 1972.Footnote 40 Ideological differences paled when it came to commodities’ trade and technological advances fuelled further production and growth. Even smaller non-aligned countries such as Yugoslavia invested heavily in developing their own energy sector and oil industry, responding to similar pressures of increased post-war consumption and mass car ownership like in Western Europe and the United States, with Belgrade being labelled ‘the only Communist capital with a parking problem’.Footnote 41 Domestically, the Yugoslav oil producing and processing industry was among the largest and employed around 19,000 people in the 1970s. Despite the dire economic situation following the second oil shock, Yugoslav experts could boast that their country ranked fourth behind the United Kingdom, Norway and Romania in terms of domestic petroleum production.Footnote 42 Yet, that could only cover around 20 to 30 per cent of overall consumption and demand. After the first oil crisis, investments were made in further geological investigations for new oil fields – in 1974 two platform ships were purchased for investigating the Adriatic Sea bed, with shale and sand deposits already discovered in Serbia, Croatia and Macedonia.Footnote 43 As a large importer of crude oil, Yugoslavia was gravely affected by the oil crises and none of these measures were enough to cover growing domestic demand.

In fact, the idea for the Adria Pipeline preceded the first oil shock and was first considered in the mid-1960s, but the global oil crisis made it all the more urgent. Experts and politicians became even more acutely aware of and concerned about the country's ‘energy dependence’.Footnote 44 Indeed, Yugoslavia had to rely increasingly on imports to supply its six domestic refineries. Although the Soviet Union figured as the main foreign supplier of oil, from the 1970s onwards Yugoslavia was importing increasingly from the Middle East.Footnote 45 Moreover, the intepretation of the first oil shock was rooted in the above-mentioned developmental paradigm that attributed most of the problems the world was facing to global structural inequalities and the North–South divide inherited from the colonial era. The energy crisis was seen as only one manifestation of the deep contradictions in which capitalism had found itself, and oil was the most obvious example of the rule and domination of multinational corporations.Footnote 46

In official NAM documents, ‘self-reliant economics’ was first mentioned in the 1964 Cairo Summit Declaration. In the 1970s the doctrine of collective self-reliance and South–South cooperation became the defining overall framework for collective action of the NAM for the restructuring of international economic relations, in particular within UNCTAD.Footnote 47 One of the principles endorsed in the ‘Declaration on the Establishment of a NIEO’ was mutual cooperation among developing countries: self-reliant development implied trade, as well as economic, financial and technical cooperation, within the developing world, based on the principles of justice and solidarity. Collective self-reliance did not imply ‘autarchic development’ and withdrawal from the international division of labour.Footnote 48 At the 1979 NAM Havana Summit, member states agreed on policy guidelines on the reinforcement of collective self-reliance, with the view of granting each other priority of supply for their exportable primary products and commodities and committed to ‘joint projects relating to the creation of production and processing capacities … in the field inter alia of petro-chemicals’.Footnote 49 Unlike domestic or national self-reliance, collective self-reliance was premised on a belief in the benefits of mutual economic cooperation and ‘the reality of interdependence of all the members of the world community’.Footnote 50 However, both member states and contemporary observers were acutely aware that actual mutual exchange was not on par with what was projected, proclaimed and desired.Footnote 51 The construction of the Yugoslav Adria Pipeline in the 1970s was not only an attempt to remedy the effects of the oil crises, but it was also an exercise in the developmental model that was ‘collective self-reliance’. A project that cut across administrative borders in a multinational federation, and that would pool resources and expertise from non-aligned, Eastern Bloc states and the UN, embodied interdependence and cooperation on two levels – both domestic and transnational.

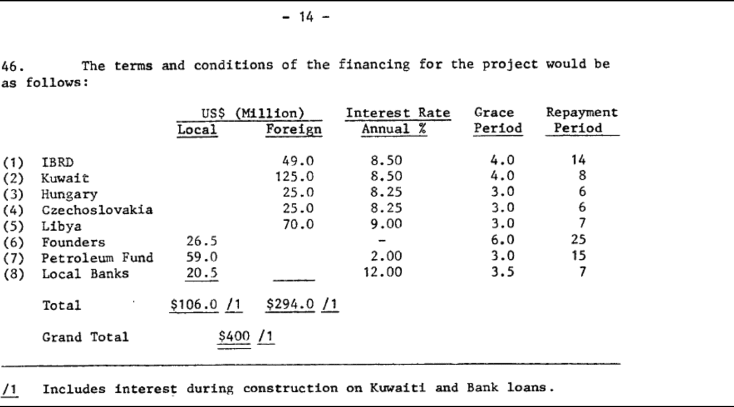

The construction of the 735 km Yugoslav Adria Pipeline that cut across both bloc and North–South divides and with support from the World Bank was, thus, not only an experiment in self-reliance but also an exercise in economic non-alignment – or, rather, strategic multi-alignment. Not only did the pipeline and the marine oil terminal literally connect Yugoslavia to Middle Eastern oil, but it also represented a concrete attempt to achieve some form of economic independence through South–South relations. It became a conduit of globalisation in the 1980s and after. Crucially, the endorsement of the project revealed an incipient geopolitical shift – it would supply Arab oil to areas which had traditionally relied on Soviet energy. Rising energy prices in the 1970s made the Soviet Union turn to more lucrative opportunities to sell its oil and gas to hard currency markets in the West and, increasingly, satellite states in Eastern Europe were becoming a burden.Footnote 52 This could explain why, in a context where Moscow ‘resented the oil committed to the bloc states’,Footnote 53 Hungary and Czechoslovakia deemed it viable to commit resources to the Adria Pipeline and decrease their dependence on Soviet energy. At the same time, Yugoslav officials began negotiations with Greece about the construction of a southern pipeline that would run from Thessaloniki in Greece through Yugoslav Macedonia and was supposed to complete a trans-Yugoslav refining and supply system. In practice, though, bold visions of self-reliance and non-alignment were more difficult to implement – the project could not go ahead until the Kuwaiti Minister of Oil pledged financial support and Libya agreed to lend $70 million towards the construction (see Table 1).

Table 1. Source: World Bank Online Archive

The World Bank estimated that imports of crude oil would increase from about 7.9 million tons in 1975 to 28 million tons in 1990 and that most of this oil would be imported from the Middle East through Adriatic ports and transported overland to the inland refineries. The World Bank, as part of the UN System, was seen by the Yugoslav elite as a trusted and reliable partner. As Dragoslav Avramović, a Yugoslav economist who spent most of his career at the World Bank and UNCTAD, recalled: ‘there was no attempt at that time on the part of the [World] Bank to change the Yugoslav system or the political structure at all, and the Bank co-existed with Yugoslavia very successfully’.Footnote 54 Indeed, by the early 1980s the Bank had approved twenty-three loans in the transport sector and five loans in the power sector, including for highways, railways, ports and a gas pipeline. Although the World Bank loan for the Adria Pipeline covered only a minor portion of the estimated cost of the overall project (13 per cent), the fact that the Bank acted as one of the funders played an important role in attracting other lenders. Indeed, the two loans by Kuwait and Libya were contingent on the bank's participation in the financing of the pipeline.Footnote 55 As a member state of the Non-Aligned Movement since the formal constitution of the movement in the 1960s, pursuing a degree of neutrality in the East–West conflict, oil-rich Kuwait was seen as a desirable economic partner. A Kuwaiti delegation also took part in the 1962 Cairo ‘Conference on the Problems of Economic Development’, although their participation was judged by the Yugoslavs as ‘passive’ at the time.Footnote 56 When Kuwait endorsed the project and confirmed its participation, Kuwait's Minister of Oil, Abdel Rahman Salem al-Atiqi, underlined that ‘Kuwait's financing would have no political conditions’.Footnote 57 Such pronouncements not only targeted Western audiences in a context where newly emboldened anti-colonial oil elites could set the terms of the debate, they also resonated powerfully with contemporary discourses on sovereign economic rights and development. However, adverse global economic trends from the late 1970s onwards, as well as debt and austerity, would soon overshadow earlier commitments to solidarity and self-reliance.

Oil Geographies in an Interdependent World

Yugoslavia's long-standing political ties with fellow non-aligned states in the Middle East and its active support for Palestine in the Arab–Israeli conflict fed into a sense of confidence and what turned out to be an overly optimistic reasoning in the immediate aftermath of the first oil shock. ‘It can be said without reservation that the latest oil price increases will not have any kind of extensive and unfavourable consequences for the Yugoslav economy next year’,Footnote 58 a Yugoslav radio commentator asserted enthusiastically in December 1973, as the world was still reeling from the OPEC-imposed oil embargo and the price increase. However, a prognosis underpinned by confidence in the strength of non-aligned solidarity soon turned out to be premature – oil imports jumped from $259 million in 1973 to $900 million in 1974,Footnote 59 causing a substantial current account deficit from which Yugoslavia would never fully recover. Indeed, the country's economic troubles and later acute economic crisis that preceded the break-up of the socialist federation could be located in the winter of 1974, when it transpired that Arab oil producers demanded the same price for their oil from Yugoslavia as they did from other countries. This turned Yugoslavia into one of the beneficiaries of the IMF's Special Oil Facility – the temporary fund that was set up to help less developed countries whose balance of payments deficits had worsened as a result of quadrupled oil prices.Footnote 60

Avoiding import dependency on a sole foreign partner meant that, even before the oil crisis, Yugoslavia sought to conclude import deals both with socialist and non-socialist countries alike. Hence, in 1967 it signed a contract to purchase crude oil from Venezuela – the first sale of Venezuelan oil to a socialist country.Footnote 61 But, proximity and political ties with the Middle East meant that non-aligned membership would prove to be the criteria for forging new links within the changing landscape of the global oil economics. Iraq ranked as Yugoslavia's top economic partner in the developing world,Footnote 62 and Yugoslav imports of Iraqi oil increased from 1,850,000 tons in 1972 to 4,794,000 in 1976.Footnote 63 After the oil crisis Yugoslavia was running a permanent trade deficit with the oil exporters, including Iraq, which the socialist federation worked to mitigate through an impressive range of ‘investment cooperation’ measures, centring on civil and military engineering projects, mostly in Iraq and Kuwait, and ranging from housing projects, airports, ports and factories, to dams and classified military facilities.Footnote 64

An important, yet somewhat overlooked, aspect in the story of non-alignment and the geopolitics of oil of the past century is how oil was used to open up a much broader debate regarding primary commodities and raw materials that were seen as crucial in determining the deteriorating terms of trade for developing countries. By virtue of being part of international and Western European intergovernmental forums and organisations which were off limits for other state socialist or developing countries, Yugoslav elites were in a position to initiate or sustain these debates and often act as spokesmen for the non-aligned world.Footnote 65 As Josip Broz Tito remarked in a conversation with Emile van Lennep, the Secretary-General of the OECD: ‘once upon a time, developing countries were only a source for raw materials the prices of which were decided elsewhere. That was the case with copper, aluminium and others. The rapid development of developing countries is in the interest of industrialised nations and they should help out with loans, ensuring the stability of primary commodity prices’.Footnote 66 Empowered by the UN Sixth Special Session on raw materials and development that took place in 1974 and that resulted in the ‘Declaration on the Establishment of a New International Economic Order’, in 1975, Senegal hosted a Conference of Developing Countries on Raw Materials. The Dakar conference reaffirmed ‘the collective active support of all developing countries for any developing country engaged in the process of recovering and consolidating its sovereignty and control over its natural resources and the exploitation, processing and marketing thereof, and full control of all aspects of foreign trade’.Footnote 67 The conference expressed an ‘unreserved political support for the Declaration of the Ministers for Foreign Affairs, Finance and Petroleum of OPEC Member Countries adopted at the Algiers Conference held in January 1975, stating that the negotiations between industrialised and developing countries, proposed by the President of the French Republic, should deal with the problems of raw materials as a whole [emphasis added] and should take account of the interests of all the developing countries’.Footnote 68

An idea for a special fund to finance buffer stocks of raw materials and primary commodities was also officially put forward in Dakar. Indeed, in the immediate aftermath of the first oil shock, rich oil-producing states responded by increasing their aid to fellow non-aligned developing countries. The aid commitment of OPEC countries multiplied five times between 1973 and 1974, accounting for 3.8 per cent of their GNP, compared to 0.81 per cent of GNP allocated to development assistance by OECD countries.Footnote 69 Kuwait, for instance, established the Fund for Arab Economic Development. There was also an Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development and OPEC's Special Fund for International Development.Footnote 70 A separate Solidarity Fund for Economic and Social Development in the Non-Aligned Countries was established with an initial contribution of $1 billion by KuwaitFootnote 71 and, on Yugoslav suggestion, because of this, it was agreed that the fund's seat would be in Kuwait.Footnote 72 An emphasis on its identity as a developing country persisted into the 1980s and Kuwait's Petroleum Corporation and its subsidiaries engaged as a developing country company with developing countries’ governments.Footnote 73

However, most of OPEC aid went to Muslim majority countries, and formally non-aligned Middle Eastern states abided by their own rules of economic and political multi-alignment and development solidarity. Saudi Arabia, for instance, the owner of the largest oil reserves and biggest oil exporter, while contributing 14 per cent of its budget to assistance to other countries, directed 96 per cent of that assistance exclusively to Arab and Muslim nations.Footnote 74 In 1977 the Yugoslav president complained that Saudi Arabia ‘plays a very negative role in the Middle East. … In fact, judging by its philosophy it doesn't belong to the non-aligned at all.’Footnote 75

Thus, by the time of the Conference on International Economic Co-Operation (CIEC) in Paris which concluded in 1977, the united front between OPEC and non-aligned developing countries had begun to unravel: Arab states like Saudi Arabia happened ‘to be most closely attuned to United States thinking in general’ and seemed unlikely to use their bargaining powers to achieve major concessions for the Third World.Footnote 76 ‘Oil prices have been increased again’, complained Miloš Minić, Yugoslavia's Minister of Foreign Affairs at the time and a participant in the Paris Conference. ‘OPEC has yet to agree to give more money to the developing countries. As far as oil is concerned, Yugoslavia has to pay $2 billion more this year than it paid for the same quantity of oil in 1978. You can imagine the position of countries economically weaker than Yugoslavia; such countries cannot wait much longer.’Footnote 77 A sense of unease and urgency was apparent even before the second oil shock the following year. The Dakar agenda and the non-aligned insistence on approaching North–South discussions on primary commodities as a whole also began to unravel as industrial powers insisted on focusing on energy and oil in particular. ‘We engaged in complex negotiations day and night’, Minić later recalled. He continued:

The group of the developing countries presented their solutions, having worked very hard on them in order to resolve acute and long-term problems. I believe that their contribution is still relevant and helpful, but the developed countries would discuss nothing but the problem of energy. They presented a proposal for establishing an international organisation to deal with energy. For them, energy was the only problem. They would state the problems, and be content to propose solutions on another occasion. Of course, it is not possible to accept this manner of solving problems. The developing countries were in favour of a comprehensive solution of all the connected problems, not just the problem of energy which is obviously of greater interest to the developed countries than to the developing countries.Footnote 78

Yet, energy remained high on the agenda. Talking to the Director of the IMF Jacques de Larosière in 1979 at the time of the WB/IMF general assembly in Belgrade, the Yugoslav president agreed that inflation was a serious, global problem that affected both developed and developing countries, but not in equal measure: ‘inflation is also fuelled by the growing gap between developed and developing countries because of the short-sighted politics of the former. The accelerated development of the latter which today would require an advantageous solution to developing countries’ energy problems is also the road to recovery for the developed world’.Footnote 79 The Yugoslav federal secretary for finance reiterated the familiar position that working towards a New International Economic Order would equally benefit both the developed and the developing world. However, the attempts to tie the question of oil to other developing countries’ primary commodities or use it as leverage eventually proved futile as price wars and inter-state conflict in the 1980s destroyed OPEC's unity. Officially, Yugoslav representatives and the movement stuck to a holistic view of international economic relations and continued to pioneer the argument that the economic fortunes of the world were interlinked and therefore the solutions had to be global.Footnote 80

Nevertheless, by the time of the New Delhi Non-Aligned Summit in 1983 it had become clear that OPEC solidarity with the developing countries was now a thing of the past. The suggestion to set up a South Bank funded with OPEC money that would help decrease the debt burden of non-oil producing countries struggling to service their debt was ignored, as the Saudi king stayed away from the summit ‘to escape demands for cash’ and the Emir of Kuwait left the New Delhi summit after the first day.Footnote 81 Arguably, the refusal of the OPEC states ‘to come to the aid of their Non-Aligned brethren by supplying a capital subscription of $1,000 million’Footnote 82 – which amounted to less than 3 per cent of the increased revenue that OPEC states drew in 1979 from other developing countries by virtue of the oil price increase – pushed poorer countries to turn for concessions towards the West and precipitated the 1980s’ debt crisis.

Kuwait, however, would remain an important economic partner and Yugoslavia's principal non-Western creditor and member of the Paris Club for Yugoslavia.Footnote 83 The country's rise to prominence in Yugoslavia's foreign relations encapsulates the profound change the relationship between Yugoslavia and the Arab oil producers had undergone from its original status of cooperation as equal partners to the fact that oil wealth dictated a specific balance, or rather, hierarchy of power. Struggling with rising inflation and balance of payment problems throughout the 1980s and having subscribed to import liberalisation as part of its 1988 stabilisation package and standby arrangements with the IMF, Yugoslav authorities saw an opportunity in engaging with oil-rich non-aligned partners on more pragmatic terms. Ideals and interest were indeed always intertwined and it is impossible to pinpoint a moment in the 1980s when they became uncoupled; however, whereas ideals couched in the language of economic decolonisation, a new international order and sovereign rights might have underpinned and dominated earlier forms of non-aligned multilateralism and cooperation, by the end of the 1980s a generational shift in international organisations and in individual countries’ elites (including Yugoslavia), coupled with the decline of state socialism and ‘global Keynesianism’ and the rise of a new ‘neo-liberal’ consensus, tipped the balance in favour of interest and profit. Hence, although still not completely divorced from the ethos of sovereignty and non-alignment, more lucrative economic trade centring on oil and weapons took precedence: in 1989 Yugoslavia joined the Soviet Union, the United States, France and the United Kingdom in procuring the Kuwaiti military with state of the art equipment by signing an $800 million ‘advanced military equipment’ deal consisting of 200 Yugoslav-made M-84 tanks that were eventually deployed during the Gulf War the following year.Footnote 84

Following Iraq's invasion of Kuwait, the Yugoslav government, which was chairing the Non-Aligned Movement after having hosted the last NAM Cold War Summit in 1989, condemned the aggression and annexation and called for an immediate and unconditional withdrawal of Iraqi troops.Footnote 85 As oil wealth had turned both Iraq and Kuwait into important economic partners and buyers of Yugoslav military equipment and expertise, this presented Yugoslavia with an inconvenient dilemma. However, the principle of national sovereignty and non-aggression prevailed: the Yugoslav government endorsed the imposition of sanctions on Iraq, despite the fact that the country faced grave consequences in terms of oil imports and the large investment projects Yugoslav companies were involved with in Iraq. ‘The negative effects of the implementation of Security Council resolution 661 on the Yugoslav economy would amount to nearly US $3 billion’Footnote 86, wrote the Yugoslav Foreign Minister to UN Secretary-General Perez de Cuellar, not knowing that the very principles his government stood for in the case of Kuwait, not least territorial integrity and de-escalation of tensions, would come to haunt his own country the following year. Arguably, the energy interdependence between Kuwait and the West, along with a geopolitical shift away from strategic European Cold War regions such as Yugoslavia, enabled the mobilisation of international support for Kuwait during the Gulf War, in contrast to Bosnia-Herzegovina ‘whose bloody dismemberment elicited little but appeasement from the same countries that mobilized a huge military force to liberate Kuwait’.Footnote 87

Although the dissolution of Yugoslavia is beyond the scope of this article, a global political economy lens can shed different light on some of the long-term causes and consequences of the Yugoslav drama. Future studies could take seriously the importance of the dynamics of external energy crises in an interdependent globalised economy and how they could offset unforeseen acute economic trouble and cause irreversible damage to delicate political balance in complex multinational settings.

Conclusion

Common histories of imperial legacies, anti-imperial struggles and economic underdevelopment and dependence played a fundamental role in the entangled Cold War histories between Yugoslavia and the Middle East. Both regions emerged partially from the vestiges of the Ottoman Empire, and the new nation-states inherited a complex cultural and religious heterogeneity.Footnote 88 Indeed, a deeper understanding of and sensitivity towards the complex dynamics in multinational societies determined Yugoslavia's position within the United Nations Committee Special Committee on Palestine in 1947 and its support for a federal solution. A consistent political and diplomatic support for the Palestinian cause and the inclusion of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation as a member of the Non-Aligned Movement made Yugoslavia a trusted ally in the Arab world. Thereafter, shared visions on economic (under) development could converge and develop upon a previously agreed political platform which stemmed from Bandung and the NAM, as was the case with the first Yugoslav encounters with Gamal Abdel Nasser's Egypt and his postulates of Arab socialism.

This article embedded the connection between socialist Yugoslavia and the Middle East both within the realm of the Non-Aligned Movement and within the broader framework of international economic relations and economic decolonisation. The case of Yugoslavia sheds further light on the shifts in the longer-term trajectory from decolonisation, non-alignment and anti-colonial repertoires of development, to neo-liberal globalisation. Competing senses of triumphalism and vulnerability marked the shift from decolonisation to globalisation in the realm of the international political economy, where interdependence was seen both as an opportunity and a threat in the relations between smaller non-oil producing countries such as Yugoslavia and the rich Middle East. Adopting such a lens enables us to approach and analyse the global Cold War and the Non-Aligned Movement differently, more specifically through the debates on national and economic sovereignty and the role played by primary commodities and petroleum in particular. Beyond the purely political and diplomatic aspects, a global political economy lens opens up new venues for studying the relations and circulations between South Eastern Europe and the Middle East. Taking into account the importance of the geopolitics of oil in the non-aligned world and foregrounding the complex interplay between political and economic emancipation is essential for a more nuanced assessment of the role of the oil crises in the eventual unravelling of the NIEO and non-aligned solidarity.

Indeed, in the context of the turbulent global economy of the 1970s, relations gradually began to become reduced to profit-driven economic cooperation and exchange, albeit still within the framework and discourse of collective self-reliance, exemplified here through the project of the Adria Oil Pipeline. This was a project that was both ‘revolutionary’ and challenging on several levels – not only did it cut across intra-Yugoslav administrative borders, it also pooled resources and expertise from diverse partners: non-aligned, Middle Eastern, Eastern Bloc states and the United Nations via the World Bank. Above all, it redrew Cold War maps of energy dependence as it enabled the supply of Arab oil to a region that had traditionally relied on Soviet energy. This was probably the last project of such magnitude that embodied the particular developmentalist ethos of the New International Economic Order and the Non-Aligned Movement: mutual assistance in building domestic capacities and infrastructures and reliance on own resources and skills.Footnote 89

However, a sense of triumphalism and hope for the restructuring of international economic relations was gradually replaced with a sense of lost opportunities and eroded solidarity. Yugoslavia's non-aligned partnerships in the Middle East, after all, were not enough to shield it or the other less developed non-oil producing states in the Global South from the disastrous economic consequences of the 1970s oil shocks and high oil prices. In 1986 the Yugoslav consortium of economic institutes published the second research output of what was termed a ‘macro-project on the New International Economic Order’. Reflecting on the preceding decade, the report noted that ‘the behaviour of the OPEC member states deserves special attention. At a very delicate time in the mid-1970s, when the price of oil could have been used to ensure certain advantages in the negotiations with the developed states, and when OPEC nations had at their disposal significant financial surpluses, this was not used to enhance the unity of the developing world nor was it used to increase the collective negotiating power of the developing with the developed world’.Footnote 90

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Leverhulme Trust-funded project ‘1989 after 1989: Rethinking the Fall of State Socialism in a Global Perspective’ [grant number RL-2012-053].