No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

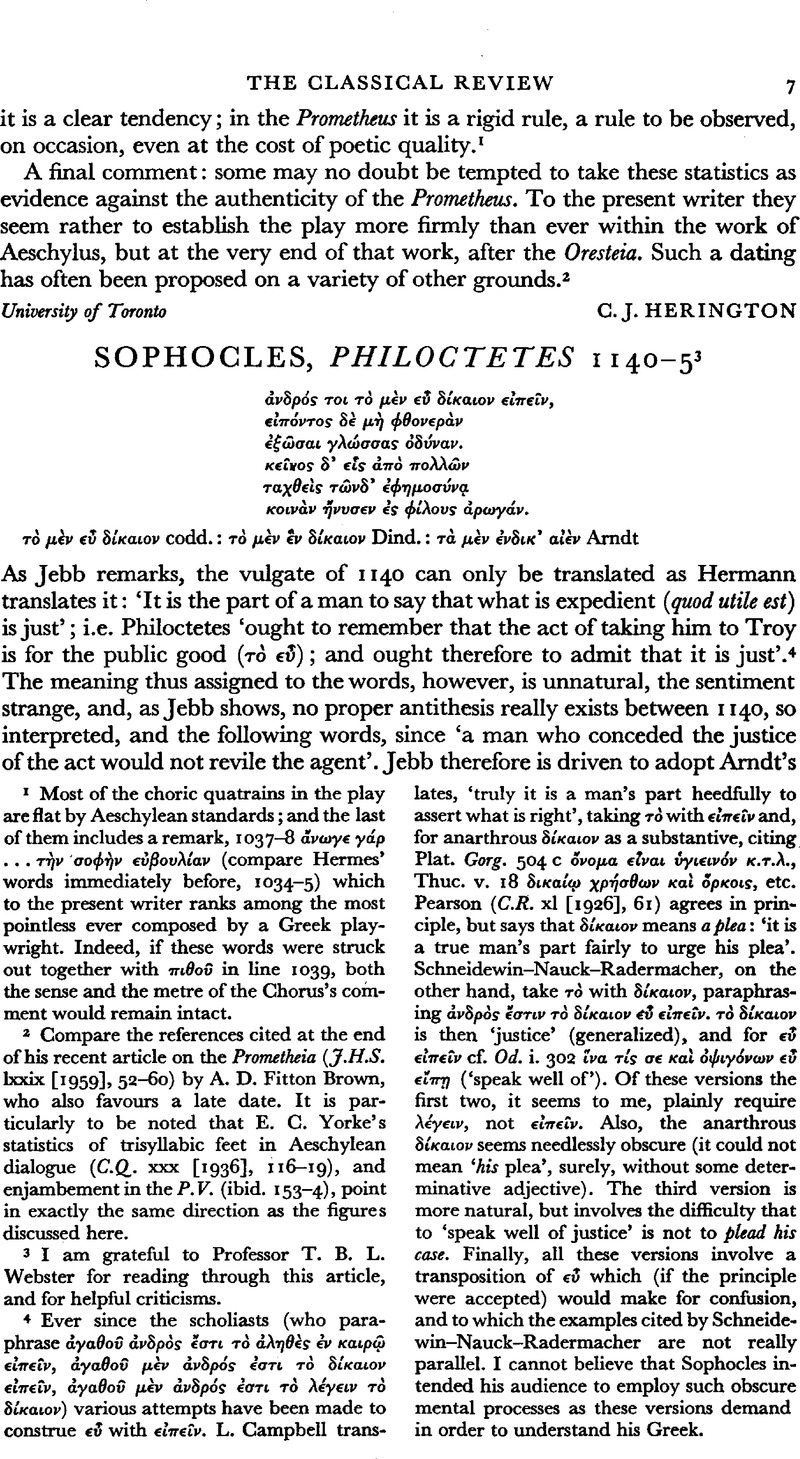

Sophocles, Philoctetes 1140–5

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1963

References

page 7 note 1 Most of the choric quatrains in the play are flat by Aeschylean standards; and the last of them includes a remark, 1037–8 ἄνωγε γ⋯ρ…τ⋯ν σοφ⋯ν εὐβουλ⋯αν (compare Hermes' words immediately before, 1034–5) which to the present writer ranks among the most prinpointless ever composed by a Greek play-wright. Indeed, if these words were struck out together with πιθο⋯ in line 1039, both the sense and the metre of the Chorus's comment would remain intact.

page 7 note 2 Compare the references cited at the end of his recent article on the Prometheia (J.H.S. lxxix [1959], 52–60) by A. D. Fitton Brown, who also favours a late date. It is particularly to be noted that E. C. Yorke's statistics of trisyllabic feet in Aeschylean dialogue (C.Q. xxx [1936], 116–19), and enjambement in the P. V. (ibid. 153–4), point in exactly the same direction as the figures discussed here.

page 7 note 3 I am grateful to Professor T. B. L. Webster for reading through this article, and for helpful criticisms.

page 7 note 4 Ever since the scholiasts (who para-phrase ⋯γαθο⋯ ⋯νδρ⋯ς ἔστι τ⋯ ⋯ληθ⋯ς ⋯ν καιρῷ εἰπεῖν, ⋯γαθο⋯ μ⋯ν ⋯νδρ⋯ς ⋯στι τ⋯ λ⋯γειν τ⋯ δ⋯καιον) various attempts have been made to construe εὖ with εἰπεῖν. L. Campbell translates, ‘truly it is a man's part needfully to assert what is right’, taking τ⋯ with εἰπεῖν and, for anarthrous δ⋯καιον as a substantive, citing Plat. Gorg. 504 c ⋯νομα εἷναι ὑγιειν⋯ν κ. τ. λ., Thuc. v. 18 δικαα⋯ῳ χρ⋯σθω κα⋯ ὅρκοις, etc. Pearson (C.R. xl [1926], 61) agrees in principle, but says that δ⋯καιον means a plea: ‘it is a true man's part fairly to urge his plea’, Schneidewin–Nauck–Radermacher, on the other hand, take τ⋯ with δ⋯καιον, paraphrasment ing ⋯νδρ⋯ς ἔστιν τ⋯ δ⋯καιν εὖ εἰπεῖν. τ⋯ δ⋯καιον is then ‘justice’ (generalized), and for εὖ εἴπῃ cf. Od. i. 302 ἵνα τ⋯ς σε κα⋯ ⋯ψιγ⋯νων εὖ εἔπῃ (‘speak well of’). Of these versions the first two, it seems to me, plainly require λ⋯γειν, not εἰπεῖν. Also, the anarthrous δ⋯καιον seems needlessly obscure (it could not mean ‘his plea’, surely, without some deter-minative adjective). The third version is more natural, but involves the difficulty that to ‘speak well of justice’ is not to plead his case. Finally, all these versions involve a transposition of εὖ which (if the principle were accepted) would make for confusion, and to which the examples cited by Schneidephrase win–Nauck–Radermacher are not really parallel. I cannot believe that Sophocles intended his audience to employ such obscure mental processes as these versions demand in order to understand his Greek.

page 8 note 1 He might also conceivably have written τ⋯ μ⋯ν οὗ δ⋯καον (cf. O.T. 1256 f. μητρῴαν δ' ὅπ*ogr;υ / κ⋯χοι διπλ⋯ν ἄρουραν οὗ τε κα⋯ τ⋯κνων) but I do not know of a parallel to the position of reflexive οὗ between the article and the noun. If he wrote ὃν, οὗ might have been an intermediate stage in the corruption to εὖ. Axt and Madvig thought of ⋯νδρ⋯ς τοι τ⋯ μ⋯ν οἶ δ⋯καιον εἰπεῖν (see Jebb's Appendix, p. 250). Jebb rejects this suggestion on the ground that οἱ cannot be used reflexively. In any case, since τ⋯ δ⋯καιον is a substantive, a possessive is required. It is curious that neither they nor Jebb thought of ὅν or οὗ.

page 8 note 2 It is worth noting that Sophocles uses δ⋯καιον as a substantive with a possessive adjective quite differently at El. 1037 τῷ σῷ δικα⋯ῳ δ⋯τ' ⋯πισπ⋯σθαι με δεῖ; There the context requires that δ⋯καιον means, not ‘your claim’, but ‘your judgement of what is right’. Both these meanings, as well as a number of others, can be paralleled from the orators. Cf. Antiph. v. 7 ⋯ αἴτησισ ⋯ν τῷ ὑμετ⋯ρῳ δικα⋯ῳ οὐχ ἧσσον ἤ ⋯ν τῷ ⋯μῷ (‘in your rights, your interest’); Dem. xix. 201 τῷ μηδ⋯ν ἔχοντι δ⋯καιον (‘no just plea, no case’); xxii. 70 ⋯π⋯ τοὺς στεφ⋯νους δ', οὓς κατ⋯κοπτεν, οὐχ⋯ προσ⋯γαγε ταὐτ⋯ δ⋯καιον το⋯το (‘requirement of justice’, i.e. that there should be a checking-official present); xxiii. 66 ⋯λλ⋯ π⋯ντες ⋯σθεν⋯στερον ἂν τ⋯ δ⋯καιον εὑρεῖν ⋯γο⋯νται περ⋯ το⋯των αὐτο⋯ το⋯ παρ⋯ το⋯τοις εὑρημ⋯νου δικα⋯ου (‘judgement’); xxiv. 142 ἔπειτ' αὐτο⋯ μ⋯ν τοὺς ἰδιώτας εἰς τ⋯ δεσμωτ⋯-ριον ἄγουςιν ὅταν ἄρχωσιν, ⋯φ' ⋯αυτοῖς δ' οὐκ οἴονται ταὐτ⋯ δ⋯καιον το⋯τ' εἶναι (‘judicial action’); xxxi. 13 μηδ' … εἰς β⋯σανον … μες' εἰς ἄλλο δ⋯καιον μεδ⋯ν καταφε⋯γειν ⋯θ⋯λοντος (‘judicial procedure’: this explains Thuc. v. 18 δικα⋯⋯ χρ⋯σθων κα⋯ ὅρκοις, i.e. ‘let them use a judicial procedure or oaths’). All these usages have to be carefully distinguished from the generalized τ⋯ δ⋯καιον— ‘justice’. It is the latter usage that is involved, if I am not mistaken, at Aesch. Suppl. 78 κλ⋯ετ' εὖ τ⋯ δ⋯καιον ἰδ⋯ντες (‘listen well to my prayer, having regarded justice well’—εὖ going with both verbs, cf. S. El. 1276–7, where τ⋯ν σ⋯ν προσώπων with both the words between which it is placed, ⋯ποστερ⋯σῃς and ⋯δον⋯ν). Mr. E. W. Handley rights, also points out to me that τ⋯ δ⋯καιον can be used generically, not for ‘justice’, but also for ’action-at-law’: cf. Menand. Epitr. 1 φε⋯γεις τ⋯ δ⋯καιον.