The so-called Latin Iliad, the main source for the knowledge of the Greek epic poem in the Latin West during the Middle Ages, is a hexametric poetic summary (epitome)Footnote 1 of Homer's Iliad likely dating from the Age of Nero,Footnote 2 which reduces the 15,693 lines of the original to a mere 1,070 lines (6.8%).

Homer's Iliad is an epic poem full of war, battle and death and long stretches of the poem, particularly the so-called ‘battle books’ (Iliad Books 5–8, 11–17, 20–2), consist of little other than fighting and a seemingly endless sequence of slaughter. These passages form the background of the narrative against which the story of Achilles’ wrath and its consequences can unfold, but hardly advance the plot. As is to be expected, many ornamental elements of the original were omitted,Footnote 3 and this brief study offers material to address the questions how the ‘Latin Homer’Footnote 4 treated other passages from his model which were not essential for the progression of the plot and in what manner he chose to adapt the copious Iliadic battle descriptions to his abridged version.

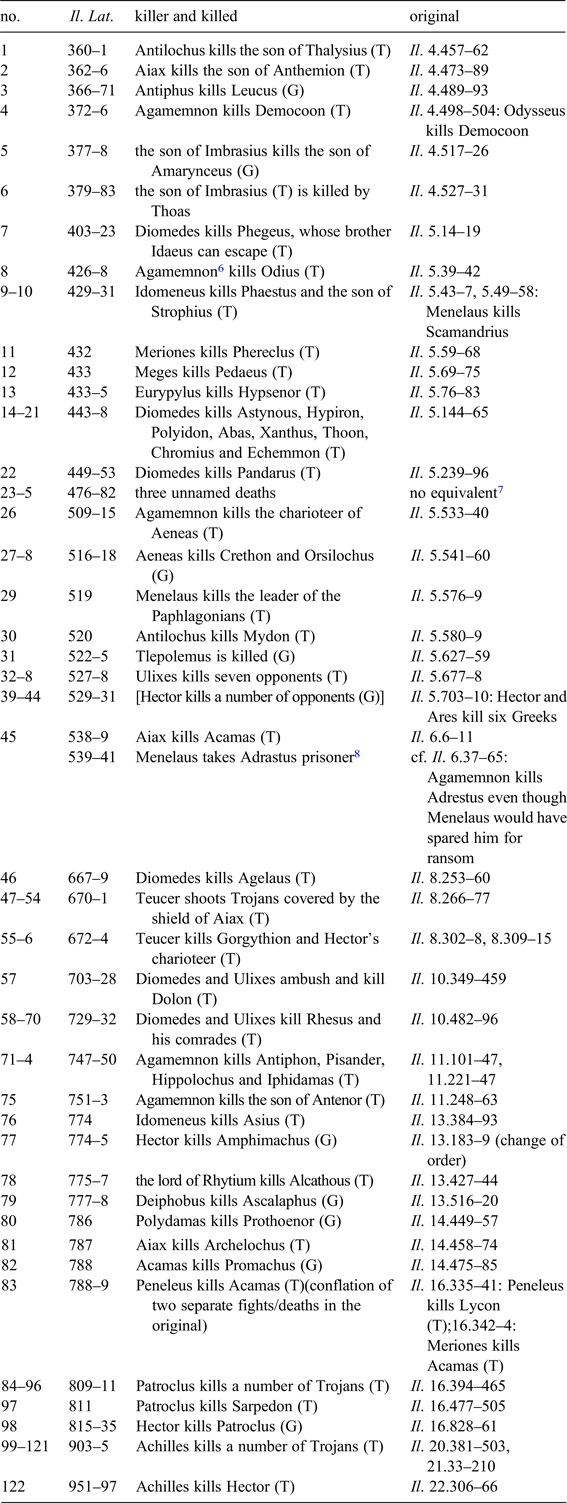

As a basis for further discussion, the following Table compiles and numbers the individually distinguishable battle deaths from the Latin Iliad with references to the original Iliadic passages. On the whole, the presentation of the battle follows the Iliadic model, with the type of ἀνδροκτασία, literally ‘man-slaughter’, the individual killing with both killer and victim named being the most common. However, there are also examples of killing catalogues, or ‘chain killings’, where a superior warrior dispatches a series of named enemies in a row (Il. Lat. 443–8, 747–50).Footnote 5 In cases where it is possible to determine the number of unnamed kills in abbreviated fighting scenes on the basis of the Homeric original, these have been added to the count (Il. Lat. 527–8, 729–32, 903–4), but descriptions of mass combat and summary slaughter (for example Il. Lat. 355–9) could not be considered for the count in the following Table. The letter in brackets indicates whether the slain individual is counted as a Greek (G) or Trojan (T) casualty. Obviously, the killer always belongs to the other side; there is no ‘friendly fire’ in ancient epic poetry.

On the whole, the individual scenes the poet of the Latin Iliad chose for his summary follow the order of the Homeric narrative quite faithfully, with only minor discrepancies,Footnote 9 and all casualties compiled in the list above have a complete or close Homeric equivalent, except for the three unnamed deaths in Il. Lat. 476–82 (a passage which is also unHomeric in other respectsFootnote 10 and therefore obviously an addition of the ‘Latin Homer’). Quite a few of the individual battle deaths presuppose the recipient's knowledge of the Homeric text, especially in cases where heroes are referred to only with a patronymic, their relation to another warrior, or a locality, and one needs to consult the Iliad to find out the proper name of minor heroes or even the number of warriors slain in summarized killings:

The first Table also makes it clear that a considerable portion of the Iliadic acts of war is represented in the summary: rather than merely summarizing battle scenes and the plot of the poem, the ‘Latin Homer’ was very much interested in the sanguinary slaughter of the Iliad, probably a hint of the prevailing literary taste in mid first-century c.e. Imperial Latin poetry (cf., for example, the tragedies of Seneca, Lucan's Civil War and Statius’ Thebaid, all of which present death and battle in an even more gruesome manner with a penchant for graphic violence). The unHomeric image of the dying warrior spewing his lifeblood from his mouth (Il. Lat. 365, 382–3, 412, 782–3)Footnote 13 is indicative of this taste for gruesome details, even though Flavian epic proceeds to offer much more drastic scenes of violence. Notably, most of the kills in the Latin Iliad are reproduced from the first half of the Homeric original, and the sequences of Iliad Books 4 and 5 are adopted almost without omissions (kills nos. 1–44, albeit sometimes without names), with some of the scenes taking up several lines, while the latter books are much less represented and only sometimes covered with descriptions of summary slaughter (for example Il. Lat. 784–5 fit maxima caedes | amborum et manat tellus infecta cruore). Thus it appears as if the ‘Latin Homer’ might have started out with a plan for a more ambitious summary, but then decided to cut down the original even more as he went along.Footnote 14

In contrast to the brevity of the Latin Iliad and considering that the poet made considerable cuts to more important episodes,Footnote 15 the number of kills adapted from the Iliad is astonishingly high and of the more than 300 individually identifiable Iliadic casualties, the ‘Latin Homer’ kept a total of 122 (more than a third),Footnote 16 even if sometimes only in nameless summaries (Il. Lat. 527–8, 670–1, 809–11, 903–5), and probably even more, since, for example, Il. Lat. 389–92 indicate a killing spree of Diomedes and lines 923–30 suggest a second rampage of Achilles against the Trojans before his final battle with Hector (both scenes with no equivalent in the Iliad). A closer look at the distribution of the named killings also yields another surprising result: the casualties in the Iliad encompass a total of 305 fighters (242 named, 63 unnamed),Footnote 17 of which 54 are Greeks (all named) and 251 Trojans (188 named), a ratio of approximately 1 to 4.6 (1 to 3.5 if only counting named kills).Footnote 18 In comparison, the Latin Iliad contains more or less explicitly the 122 kills listed above (50 named, 72 unnamed), of which only 16 are Greeks and 106 Trojans (with the three individual unnamed deaths in Il. Lat. 476–82 not attributable to any side), resulting in a ratio of approximately 1 to 6.4 (still 1 to 4 for named deaths). The skewed balance of casualties in favour of the Greeks and the consistent depiction of Greeks as more successful and superior in battle in the Iliad Footnote 19 has been explained as a pro-Greek bias on the part of the poet, but might also be interpreted as an implicit way to foreshadow the ultimate Greek victory and their sack of Troy. In comparison, the numbers for the Latin Iliad show that the ‘Latin Homer’ tipped the scales slightly more in favour of the Greeks and presented them as even more successful in battle, which is at odds with the Romans’ partiality for the Trojans (whose most influential testimony is Virgil's Aeneid).

Even though the ‘Latin Homer’ explicitly mentioned the future glory of Rome and the Julio-Claudian dynasty when the gods save the Roman ancestor Aeneas (who is credited with only two kills, nos. 27–8; Il. Lat. 483–5 contain no details and have no Iliadic equivalent)Footnote 20 from the wrath of Achilles,Footnote 21 he clearly does not unreservedly accommodate the Romans’ affinities with the Trojans—at least with regard to Aeneas, since Hector is the clear favourite of the poem, even though he also receives only two named kills (nos. 77, 98) after his extensive but inconclusive duel with Aiax in Il. Lat. 589–630, with the six unnamed summary kills nos. 39–44 barely noticeable and only detectable on the basis of the Iliad. The casualty list and the accentuation of the devastating effect of Hector's death, an aspect which is stressed several times (Il. Lat. 486 spes una Phrygum; 661 unum decus Phrygiae; 931 unus tota salus in quo Troiana manebat; 1019–20 ruit omnis in uno | Hectore causa Phrygum; also cf. 1040, 1051–6), present the prospects of the Trojan defenders as even more grim and hopeless than in the Iliad.Footnote 22 The death of Hector is the climax of the poem, and his importance as well as the impact of his death are heightened at the expense of the status of Aeneas, since all comments extolling Hector and his significance for Troy are inevitably implicit slights to Aeneas.

In conclusion, these numbers show that in consideration of the quantity of casualties, the Trojan cause is presented as even more desperate in the Latin Iliad than in its Homeric model. In this regard the numbers admittedly raise more questions than they can answer, but these lists hopefully provide material for further study and discussion as well as pose questions which future interpretations of the Latin Iliad as literature in an imperial Roman context will have to address.