Article contents

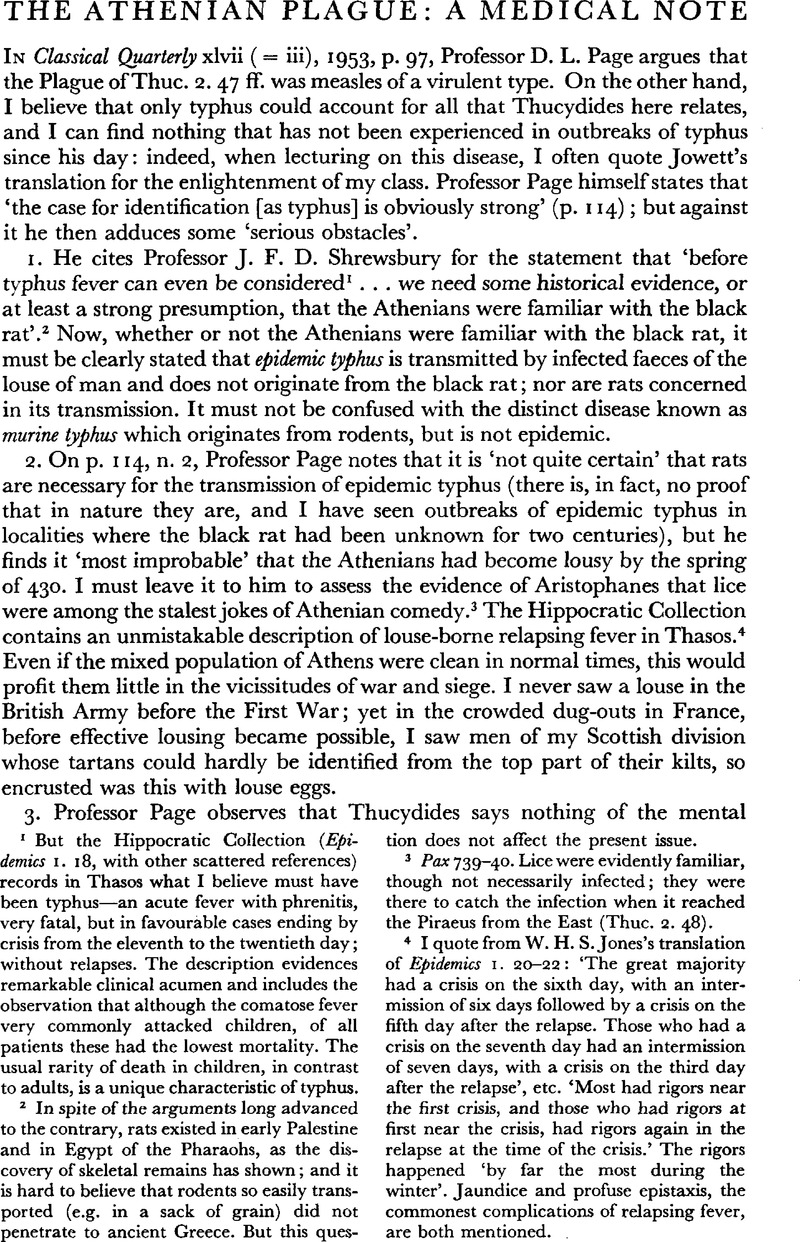

The Athenian Plague: A Medical Note

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Other

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1954

References

page 171 note 2 In spite of the arguments long advanced to the contrary, rats existed in early Palestine and in Egypt of the Pharaohs, as the discovery of skeletal remains has shown; and it is hard to believe that rodents so easily transported (e.g. in a sack of grain) did not penetrate to ancient Greece. But this question does not affect the present issue.

page 171 note 3 Pax 739–40. Lice were evidently familiar, though not necessarily infected; they were there to catch the infection when it reached the Piraeus from the East (Thuc. 2. 48).

page 171 note 4 I quote from W. H. S.Jones's translation of Epidemics 1. 20–22:Google Scholar ‘The great majority had a crisis on the sixth day, with an intermission of six days followed by a crisis on the fifth day after the relapse. Those who had a crisis on the seventh day had an intermission of seven days, with a crisis on the third day after the relapse’, etc. ‘Most had rigors near the first crisis, and those who had rigors at first near the crisis, had rigors again in the relapse at the time of the crisis.’ The rigors happened ‘by far the most during the winter’. Jaundice and profuse epistaxis, the commonest complications of relapsing fever, are both mentioned.

page 172 note 1 Thucydides is, of course, wrong in supposing that the ![]() (which, with Professor Page, I take in its technical sense of convulsions) was induced by the retching: cf. his other ascriptions of causes to symptoms, noted in the text following. It has been suggested to me that, since all madness was regarded as a form of supernatural possession, a fifth-century rationalist would be inclined to reduce any manifestation of it to causes then accepted as ‘natural’. The doctors rightly ascribed

(which, with Professor Page, I take in its technical sense of convulsions) was induced by the retching: cf. his other ascriptions of causes to symptoms, noted in the text following. It has been suggested to me that, since all madness was regarded as a form of supernatural possession, a fifth-century rationalist would be inclined to reduce any manifestation of it to causes then accepted as ‘natural’. The doctors rightly ascribed ![]() to phrenitis.

to phrenitis.

page 174 note 1 I wonder if those who persuade themselves that this epidemic was plague, or smallpox, can have had any actual experience of these diseases. Apart from the omission to mention buboes (practically conclusive in itself), the course of epidemic plague is far shorter than Thucydides indicates; most of the deaths occur within the first five days, and more than half of diem within the first three. Had the epidemic been smallpox of an equivalent intensity, there would have been many haemorrhagic cases and many more of that type of confluent smallpox where the face is transformed to a continuous sheet of pus, and the features obliterated. It is incredible that Thucydides who noticed even small blisters (common in some outbreaks of typhus especially in summer) could have failed to notice these ghastly cases.

In the typhus in the Williamite war in Ireland ‘Some had their Toes, and some their whole Feet that fell off as the Surgeons were dressing them.’ It is unnecessary to evoke ergotism to explain this symptom in Athens.

- 9

- Cited by