Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

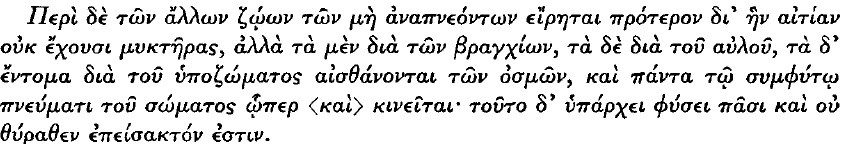

The purpose of this article is to present arguments which indicate that PA 2. 16. 659b13–19 may not be authentic.

page 270 note 1 Transl. Peck, A. L., Aristotle: Parts of Animals, London, 1961. The text is quoted as he gives it.Google Scholar

page 270 note 2 Louis, P., Aristote, Les Parties des animaux, Paris, 1956, ad loc.Google Scholar

page 270 note 3 Über die Glieder der Gesehöpfe, Paderborn, 1959. ad loc.Google Scholar

page 270 note 4 Aristotle De Partibus Animalium, Oxford, 1912, ad loc.Google Scholar

page 270 note 5 HA 4. 10. 537a31–b4: ‘The dolphin and whale, and the rest of the animals with an ![]() sleep holding their

sleep holding their ![]() out of the sea; they breathe through it, gently moving their fins. Some have even heard a dolphin snore.' (Translation based on those of Louis, , Histoire des animaux, Paris, 1964Google Scholar, and Thompson, D. W., Historia Animalium, Oxford, 1910). Cf. 8. 2. 589b1; Resp. 12, 476b13 ff. gives a longer, and equally vivid, description of the breathing of dolphins and others with an

out of the sea; they breathe through it, gently moving their fins. Some have even heard a dolphin snore.' (Translation based on those of Louis, , Histoire des animaux, Paris, 1964Google Scholar, and Thompson, D. W., Historia Animalium, Oxford, 1910). Cf. 8. 2. 589b1; Resp. 12, 476b13 ff. gives a longer, and equally vivid, description of the breathing of dolphins and others with an![]() Google Scholar

Google Scholar

page 271 note 1 HA 4. 1. 524a10; PA 4. 5. 679a3; GA 1. 15. 720b32. Aristotle does not seem to have spotted the olfactory sac of the cephalopods, located just below the eye.

page 271 note 2 HA 4. 8. 533a34–65, Thompson's translation. On the reference to the brain, cf. GA 2. 6. 744a2–3, quoted below. The nostril-like parts are olfactory organs in fish, and are connected to the brain with nerves; Aristotle was looking for a connection by means of blood vessels. Cf. Solmsen, F. (Museum Helveticum xix [1961], 150–67, 169–97).Google Scholar

page 271 note 3 HA 4. 8. 534a11–535a25; Sens. 5. 444b7 ff.

page 272 note 1 Cf. Bonitz, Index s.v.![]() Google Scholar

Google Scholar

page 272 note 2 They refer to HA 4. 9. 535b8, where the tympanum of cicadas is described as ‘the membrane under the ![]() ’, and to PA 659b17.

’, and to PA 659b17.

page 272 note 3 Hett, W. S., Aristotle On the Soul, etc., London, 1936.Google Scholar

page 272 note 4 HA 4. 7. 532b16; 9. 535b8; 5. 30. 556a18; Resp. 9, 475a1 ff. Data on anatomy of the cicada are from Haskell, P. T., ‘Sound Production’ in The Physiology of Insecta, ed. Rockstein, M., New York, 1964, i. 563 ffGoogle Scholar. and from H. and Frings, M., ‘Uses of Sounds by Insects’, Annual Review 0/Entomology iii (1958), 87–106.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

page 272 note 5 2. 482a17. Oddly enough, Hett translates ‘diaphragm’.

page 274 note 1 Cf. Block, I., PQ xi (1961), 1–9CrossRefGoogle Scholar, AJP lxxxii (1961), 50–77Google Scholar, Phronesis ix (1964), 58–63.Google Scholar

page 275 note 1 In Somn. Vig. 2. 456a1 ff. both movement and the dominant sense faculty are in question.

page 276 note 1 10. 703a9–28. In Somn. Vig. 2, there is something of a contrast between ‘holding the external breath’ and ‘holding the connate ![]() ’ to make strength for movement. The distinction between ‘increasing one’s strength’ and ‘using a general instrument of movement’ seems blurred in the PA passage.

’ to make strength for movement. The distinction between ‘increasing one’s strength’ and ‘using a general instrument of movement’ seems blurred in the PA passage.