Approximately one-third of infants born with CHD will need urgent surgery in infancy and those who present in a poor condition are at the highest risk from the procedures. 1 During the decade 2000–2010, the paediatric cardiac surgery case mix became more complex with an increased prevalence of functionally univentricular hearts, high-risk diagnoses, and low weight at operation (<2.5 kg). Reference Brown, Crowe and Franklin2 The National Congenital Heart Disease Audit 1 (2020) reports 284 Norwood procedure surgical cases during 2016–2019 in the United Kingdom and Ireland, with a 93% 30-day survival (n = 264); equivalent to approximately 95 cases per year across the United Kingdom. Infants with these complex conditions have the highest mortality and morbidity between the first and second operations, remaining fragile after their first surgery and in the early weeks after discharge home. Reference Crowe, Ridout and Knowles3

Parents need to be adequately prepared for discharge during this critical time and supported at home between the first and second stage of surgery. Reference Tregay, Brown and Crowe4–Reference Gaskin, Wray and Barron6 However, parents can find it challenging to follow an escalation plan, despite education and training when their child is discharged home. Reference Tregay, Brown and Crowe4 In addition, parents can feel that their concerns about their infant are not taken seriously and that local health professionals do not always have the knowledge and information to respond quickly or appropriately. Reference Tregay, Brown and Crowe4,Reference Gaskin, Barron and Daniels7

The original Congenital Heart Assessment Tool (CHAT) Reference Gaskin, Wray and Barron6,Reference Gaskin, Barron and Daniels7 was developed in 2012 by a group of clinicians, parents and CHD charity members, using the principles of paediatric early warning scores and a national traffic light tool. Reference Haines8–11 It is a community-based early warning tool using a traffic light system to support decision-making by parents, carers and community teams and escalate early signs of deterioration in infants with complex CHD as part of a home-monitoring programme (HMP). The CHAT was designed for use with a specialist group of infants with complex functionally univentricular CHD. Reference Gaskin, Barron and Daniels7 These infants have emergency surgery soon after birth or post-natal diagnosis and will usually require at least two further heart operations. Infants are most fragile between the first and second surgery, the interstage period, due to the single ventricle being dependent on the flow of blood through a shunt and the young age of the infant. Reference Hehir and Ghanayem12

Vigilance by families and carers in optimising the outcome of their infants in the first year of life within this patient group has been demonstrated. Reference Meakins, Ray and Hegadoren13,Reference Rempel, Ravindran and Rogers14 Enhanced surveillance and early identification of deterioration in physiology reduce mortality risks and support optimal growth to undertake second-stage cardiac surgery. Reference Hehir and Ghanayem12,Reference Rudd, Frommelt and Tweddell15 Single centre studies report a reduction in interstage mortality using a HMP, which enhances surveillance and early escalation of concerns. Reference Ghanayem, Hoffman and Mussatto16–Reference Hansen, Furck and Petko19 This interstage period is when HMP and the CHAT are used to enhance safety, quality of care and care efficiency.

Empowering patients to engage with community services is a priority in new models of care. 20 Projects that bridge inpatient and outpatient care are crucial to meet the needs of our future infants and families in the current National Health Service climate. Implementation of the CHD Standards and Service Specifications 21 was a key driver for this quality improvement project. The patient and family involvement groups from the National Health Service England review 22 raised concerns about the inconsistency across services and the need to raise standardisation by care bundles and pathways between different centres and across inpatient/outpatient care. The review 22 also highlighted the importance of keeping care close to the patient’s and family’s home, which could be met in part with HMPs.

At the time of planning this quality improvement project, there were no other community-based early warning tools available for use by parents or carers of infants with complex CHD in the United Kingdom. There remains a gap in the research regarding early warning tools for parents and carers in the community setting; however, there is potential for the CHAT to be implemented nationally.

The principal aim of the collaborative quality improvement project was to enhance safety mechanisms for these fragile infants. The secondary aim was to evaluate the wider implementation of an early warning tool (CHAT) Reference Gaskin, Barron and Daniels7 within a HMP for infants with complex CHD in the community setting, across four children’s cardiac centres.

The objectives of the quality improvement project were:

-

1. To review the content of the CHAT Reference Gaskin, Barron and Daniels7 (phases 1 and 2)

-

2. To further evaluate the effectiveness of CHAT and incorporate CHAT into the discharge planning and current HMPs in the four children’s cardiac centres (phases 3–5)

-

3. To provide an updated standardised tool (CHAT2) to assess infants and escalate concerns (phase 8)

Materials and method

Design and setting

A mixed-methods quality improvement design using a plan, do, study, act (PDSA) cycle of improvement 23 was undertaken (Fig 1).

Figure 1. The plan, do, study, act cycle.

The project was conducted over an 18-month period between 2016 and 2018, comprising a 3-month planning phase (August–October 2016) and 12 months implementation (do/study) phase (November 2016–October 2017) at four specialist children’s surgical centres and the University of Worcester. The implementation phase was extended to include stakeholders attending the Little Hearts Matter open day (March 2018).

Funding was received from the Health Foundation ‘Innovating for Improvement’ programme, which aimed to initiate measurable improvement by applying scientific methods within healthcare settings. 24 National Health Service ethical approval was not required as it was assessed as an improvement project in agreement with each of the individual children’s cardiac units’ Quality Improvement Teams and the University of Worcester Institute of Health and Society Ethics Committee.

Planning stage

The “planning” stage included two review phases to meet the first objective:

-

1. Cardiac nurse specialists meeting to discuss baseline HMP practice in the four centres (phase 1)

At baseline (August 2016), a national HMP did not exist in the United Kingdom for infants with complex CHD. One of the centres did not discharge their fragile infants between stages 1 and 2 of cardiac surgery, resulting in an extended inpatient stay, increased inpatient costs and bed occupancy. Furthermore, whilst the other three HMPs were based on models of care from the United States of America Reference Ghanayem, Hoffman and Mussatto16,Reference Ghanayem, Cava and Jaquiss17 , the Cardiac Nurse Specialist teams identified variations in practice. For example, educational packages were delivered to parents before discharge, but there was a lack of structured assessment of parental/carer suitability for the HMP. Furthermore, only one centre was using the definition of “clinical consultation” to code for income generation.

-

2. Review of the CHAT Reference Gaskin, Barron and Daniels7 and discussion with paediatric early warning system experts (phase 2)

The project lead (LS) reviewed the original CHAT Reference Gaskin, Barron and Daniels7 ; the “Sepsis 6” Reference Daniels, Nutbeam and McNamara25 and the “fever in the under 5s” guideline Reference Roland, Lewis and Fielding26 and asked clinical experts who had developed the paediatric early warning tool Reference Chapman, Wray and Oulton27 and paediatric observation priority scoring system 24 to review the CHAT. Chapman’s team Reference Chapman, Wray and Oulton27 had identified the importance of “parental concerns” in the assessment of children and young people and during communication with a clinical professional. At the end of this planning stage, the CHAT was modified (CHATm) with addition of a sixth domain “parental response” and changes to the font, size, layout and to some of the wording to reduce complexity and enhance parental understanding (Fig 2).

Figure 2. The modified CHAT (CHATm).

Do stage: The intervention methods and participants

Due to the small number of infants requiring surgery for a functionally univentricular heart annually in the United Kingdom 1 and going home until the second stage of surgery, the “do” stage was designed to compensate for this by using a variety of implementation measures to test the effectiveness of the CHATm (objective 2).

Phases 3, 4, and 5 are presented in this paper; phases 6 and 7 in paper 2 Reference Gaskin, Smith and Wray28

-

3. Case note review using CHATm

-

4. Tabletop simulation exercise using CHATm

-

5. Parental use of CHATm at home

-

6. Clinical simulation exercise

-

7. Parent simulation workshop

Participants and methods

Phase 3 Case note review

The method of evaluation was a retrospective review of clinical notes documented during June 2016 till June 2017. Firstly, the project team determined whether each centre had documentation that was coded according to the definition of “clinical consultation” 29 and only case notes coded in this way were included in the review (n = 462).

A standardisation exercise using 10 clinical scenarios and the CHATm was conducted with the review team (by LS) before the case notes were reviewed. The review team included experienced Cardiac Nurse Specialists (n = 3) and qualified Advanced Nurse Practitioners (n = 3).

Phase 4: Tabletop exercise

Simulation was used as the investigative methodology Reference Lamé and Dixon-Woods30,Reference Cheng, Grant and Auerbach31 to assess the feasibility and usability of CHATm in practice. Ten simulated clinical scenarios were created (by LS) using real examples, including a sample of red, amber, and green triggers.

A convenience sampling strategy was used to invite health care professionals, who met the following inclusion criteria, to participate:

-

1. Work in a cardiac network (surgical centre, cardiology centre, or local centre)

-

2. Have an interest in paediatric cardiology (work outside of a cardiac network)

-

3. Have a fragile infant on their caseload (community teams)

Paper or electronic copies of the 10 scenarios were provided to participants (n = 52) with a copy of the CHATm. Participants were asked to spend a maximum of 15 minutes to decide upon the red/amber/green rating for each scenario and were asked to additionally provide written comments on each scenario. Participants were asked to return the completed scenarios to the project lead.

Phase 5. Parental use of CHATm at home

A purposive sampling strategy was employed. During November 2016–August 2017, parents of infants deemed suitable for discharge home after clinical, psychosocial, and safeguarding assessment were invited to use CHATm by the Cardiac Nurse Specialist Team. Exclusion criteria were parents with psychosocial issues, non-English speaking or who could not understand the CHATm. Participating parents were prepared for discharge by the Cardiac Nurse Specialist team using the standard discharge advice, the standard HMP preparation, and the CHATm. Parents were asked to assess their infant using the CHATm daily and to give feedback about using the CHATm to the Cardiac Nurses Specialists, who were asked to record any amber or red triggers initiated by these parents.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis was undertaken for phase 3 and affinity mapping 32 was used to analyse the data arising from phases 4 and 5.

“Study” stage

Phase 3. Case notes review

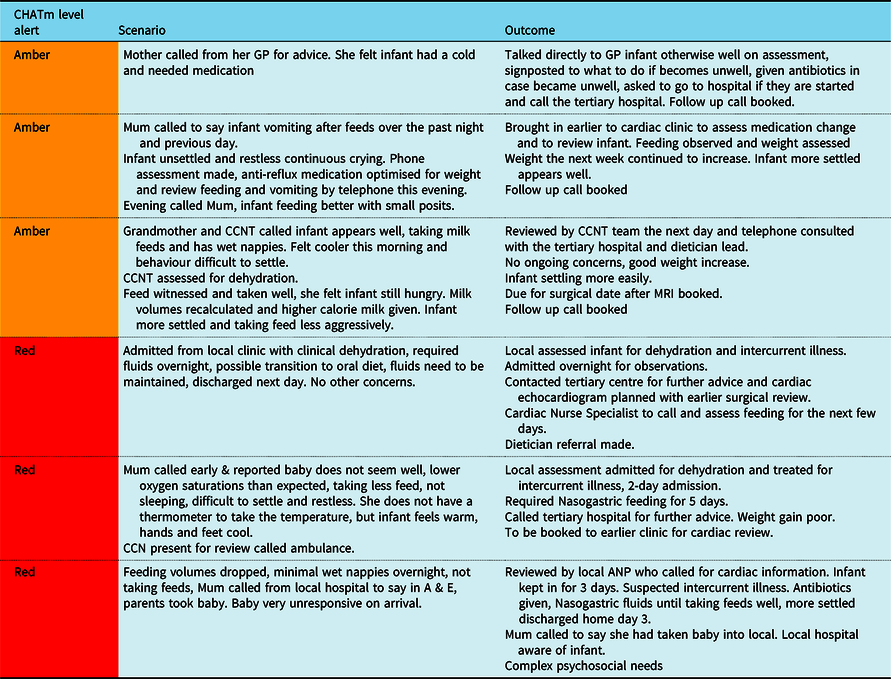

The review team identified n = 462 documented “clinical consultations” for review, using CHATm. A total of 38 triggers, red (n = 24), and amber (n = 14), were identified. Examples of these triggers are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Examples of CHATm triggers in clinical records (phase 3)

ANP = Advanced nurse practitioner; A & E = Accident and emergency department; CCN = Children’s Cardiac Nurse; CCNT = Children’s Cardiac Nurse Team; GP = General Practitioner

Phase 4. Tabletop scenarios

Participants (n = 52) included cardiac network nurses (n = 24), medical staff (n = 11), and health care assistants (n = 2); paediatricians with an interest in paediatric cardiology (n = 6) and community nurses (n = 9). Ten scenarios were given to each participant (n = 520 scenarios). In total, 508/520 (99%) scenarios were completed, and all identified the correct green/amber/red trigger for each scenario.

Comments received included: “Easy to use and understand, clear to follow and score” (nurse); “Very useful tool for community support teams” (community nurse); “Great way to work with the family, parent, carer” (HCA); “What happens if you do not speak English or read English?” (HCA2). Other responses related to training and education for staff and parents, escalation process and contacts and clarity of the descriptions in the CHATm (Table 2).

Table 2. Phase 4 Comments about “tabletop scenarios”

Phase 5. Parental use of CHATm at home

During November 2016 to October 2017, parents of infants being prepared for discharge following complex surgery (n = 12) were identified. Six families were assessed by the medical, nursing, and psychology teams as not suitable for participation due to psychological issues (n = 3), their understanding of CHATm (n = 1), or English not first language (n = 2). Six families participated (white British n = 1, white European n = 3, Bangladesh n = 1, Pakistan n = 1).

Most of the parents (83%, n = 5/6) used the management guidance in CHATm appropriately to raise amber and red concerns. The amber triggers (n = 3) initiated contact with the tertiary centre or the Cardiac Nurse Specialist. The red (n = 3) triggers (Table 3) all resulted in hospital review or admission; however, one of these parents phoned the cardiac nurse specialist first before taking their infant to the local hospital. Parents’ feedback regarding their use of CHATm suggested that they found the CHATm training useful before discharge and did not need to use the CHATm every day, only when they were concerned (Table 4).

Table 3. Examples of CHAT triggers for families at home

CCN = Children’s Cardiac Nurse; CNS = Clinical Nurse Specialist; NG=nasogastric

Table 4. Phase 5 Parents’ comments about CHATm

“Act” stage

This QI project evaluated the efficiency, effectiveness, and usability of the CHATm through five intervention phases (3–7). Phase 3 (case notes review) provided active involvement, learning, and exposure to CHATm for the Cardiac Nurse Specialists and Advanced Nurse Practitioners involved in the care of these infants and families, developing their confidence in using the CHATm. Phase 4 participants (tabletop exercise) perceived a benefit of practically using the CHATm through simulation; they recognised how the CHATm could effectively indicate amber and red triggers, the action required and escalated parents’ concerns to professionals. In phase 4, participants identified that robust and nationally agreed training for all staff that will use the CHATm is necessary to ensure successful and complete implementation. Suggestions relating to the definitions and words used within the CHATm and how to fully prepare parents to use the CHATm were also provided.

In phase 5 (parental use of CHATm), a key finding was the need to develop a structured and standardised model to assess parental suitability to go home with the HMP and CHATm. Parents using CHATm explained that whilst they might not use the tool daily, it provided useful knowledge and information prior to discharge from hospital and in preparation for going home. They felt that the tool also supported their decision-making and discussions with health care professionals.

As a result of specific feedback about the content and format of CHATm, further modifications were made, resulting in the creation of a finalised second version of the CHAT in the final “Act” stage of the project (referred to as phase 8). This was called “CHAT2” and is presented in paper 2Reference Gaskin, Smith and Wray 28 .

The expert consensus arising from the discussions (phase 1) led to creation of a standardised “bundle of care” (Fig 3), incorporating three components: parental assessment/education, the HMP and consideration of individual risks. The CHATm was included within each component, which was updated to CHAT2 at the end of the PDSA cycle (phase 8 presented in paper 2). The further development of CHAT2 contributes to the vision to develop robust bundles of care to support acute specialised care in the community setting, using a virtual ward environment and standardising children’s cardiac pathways. 21,33 It also contributes to setting national cardiac safety standards at discharge. 20 The development and implementation of a National standardised “bundle of care” for these infants need further evaluation.

Figure 3. Bundle of care.

During the ‘Act’ stage, collaboration with the National children’s CHD standards review group was initiated. Preliminary meetings were held with commissioners regarding Univentricular Commissioning for Quality and Innovation 34 and this encouraged involvement of Paediatricians with Cardiac Expertise. The aim of these early discussions was to add the CHAT2 into the Commissioning for Quality and Innovation 34 and expand the remit to support a wider infant group, supporting wider national engagement. In the London network, a dialogue was initiated with the rapid response lead paediatricians for unexpected child deaths regarding the CHAT2 and the proposed Home Monitoring Bundle. The project group engaged with the wider children’s community services, with feedback from paediatricians with expertise in Cardiology, Community Children’s Nurses, Health Visitors, and nursing assistants.

The introduction of electronic records and wider electronic documentation Reference Sipanoun, Oulton and Gibson35 at a national level will be beneficial to communication across all care domains. However, there remains a lack of electronic connections between tertiary and primary care, which makes real-time working a continuous challenge, especially if an infant is sick or deteriorating. It also places increased pressures on the infant’s family to hold health records and specialist knowledge. Development of a mobile application for parents to measure, transmit, and record parent assessment using CHAT2 to the clinical teams through a virtual ward environment 21,33 would address some of these challenges. Several grant applications since the project ended in 2018 have so far been unsuccessful. Unfortunately, the clinical impact of the COVID-19 pandemic during 2020 and 2021 has further hampered progress in terms of wider communication about the project. Development of a mobile application may also support parental electronic records.

There is potential for translation of CHAT2 into different languages; extension of the tool for all infants and young children being discharged after cardiac surgery; and potential to develop another version for older children following later stages of surgery.

Limitations

A challenge encountered was an underestimation of the diversity of service provision across the four centres and the increased time and resources needed for effective communication at a national level. For future similar studies, we would include regular telemedicine links in the costs. This would have helped mitigate some of the time and logistical issues the team faced in terms of getting together.

Furthermore, the project demonstrated challenges relating to families not using the CHATm because they do not understand or speak English; therefore, future work needs to include translation of CHAT2 into different languages to meet the ethnic diversity of this population. Reference Knowles, Ridout and Crowe36

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Cardiac Nurse Specialists, Cardiologists and Cardiac Surgeons at the Partner organisation(s):

Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust

University Hospitals Southampton NHS Foundation Trust

The Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne NHS Foundation Trust

Birmingham Women’s & Children’s NHS Foundation Trust

Suzie Hutchinson, CEO, Little Hearts Matter We would also like to thank Sue Chapman, Dr Roland, the nurses, community nurses, student nurses, medical staff, health care assistants, parents and visitors that took part

Financial support

This project was funded by the Health Foundation, Innovating for Improvement, round 4, Unique Award Reference Number: 7709.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Agreement was received from each of the individual children’s cardiac units’ Quality Improvement Teams and Ethical Approval from the University of Worcester for phases 6–7.