Introduction

Involvement of the peripheral nervous system occurs in 5% of patients with lymphoma,Reference Hughes, Britton and Richards 1 and may be noted at any stage in the disease evolution. Neurolymphomatosis (NL) refers to direct infiltration of the endoneurium by lymphoma cells, a process which must be distinguished from compression of nerves by adjacent lymphadenopathy or extranodal lymphomatous masses. Neurolymphomatosis must also be distinguished from meningeal lymphomatosis (subarachnoid epineurial seeding without direct perivascular invasion of spinal nerve roots)Reference Lachance, O’Neill and MacDonald 2 , Reference Stark and Mehdorn 3 and the wide range of immune-mediated paraneoplastic neuropathy.Reference Graus, Arino and Dalmau 4 Several additional etiologies may contribute to the development of neuropathy in patients with lymphoma, such as chemotherapy, radiation toxicity, malnutrition and infection.

The present series illustrates patterns of brachial plexus invasion in lymphoma, ranging from focal distal mononeuropathy to nodular or diffuse brachial plexopathy. Emphasis will be given to the differential diagnosis of NL and the role of neuroimaging in diagnosis and staging.

Case 1

This patient first presented at age 48 with cutaneous B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, stage 1EA, which was managed with local radiotherapy. At age 58, she had a recurrence with femoral adenopathy, treated with six cycles of Cytoxan, Hydroxyrubicin, Oncovin, Prednisone (CHOP) chemotherapy. At age 65, recurrent lymphoma required local radiotherapy and fludarabine. Subsequent cervical lymphadenopathy was treated with courses of cyclophosphamide and rituximab.

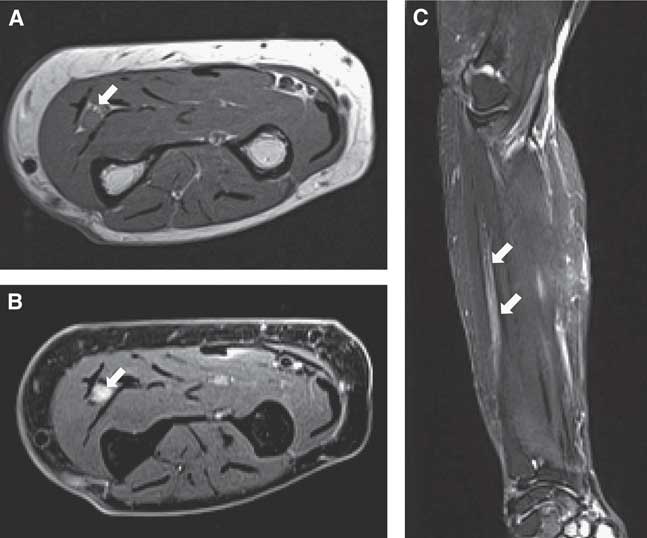

At age 78 she was referred to the neuromuscular clinic for symptoms of numbness, paresthesia and pain along the ulnar border of the left hand. There was well-delineated sensory loss in the ulnar territory. There was marked atrophy and weakness of all left interosseous muscles. Electrodiagnostic studies demonstrated marked motor and sensory axonal loss confined to the territory of the left ulnar nerve. There was also partial motor conduction block in the ulnar nerve in the proximal forearm, suggesting focal demyelination (Table 1). An FDG-PET/CT scan did not show evidence of recurrent systemic lymphoma, though the study, as per institutional protocol, excluded the forearm from the field of view. MRI of the forearm without gadolinium enhancement showed fusiform thickening of the left ulnar nerve over a length of 10 cm, at the level of the proximal-mid forearm (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Case 1. Axial T1 (A), axial proton density with fat saturation (B) and coronal T2 sequence with fat saturation show a fusiform thickening of the left ulnar nerve, in the proximal-mid forearm (arrows). The signal intensity of the nerve is mildly increased in the axial PD and coronal T2 sequences with fat saturation.

Table 1 Case 1. Ulnar motor and sensory nerve conduction studies

There is significant axonal loss on the left side (marked reduction in ulnar compound motor and sensory amplitudes with distal stimulation) as well as partial motor conduction block between Wrist and Elbow stimulation points (drop in amplitude from 2.6 to 1.0 mv, a 62% decrease). The tracings below represent the left ulnar compound muscle action potential waveform with stimulation at the wrist (W), below-elbow (BE) and above-elbow (AE) stimulation sites.

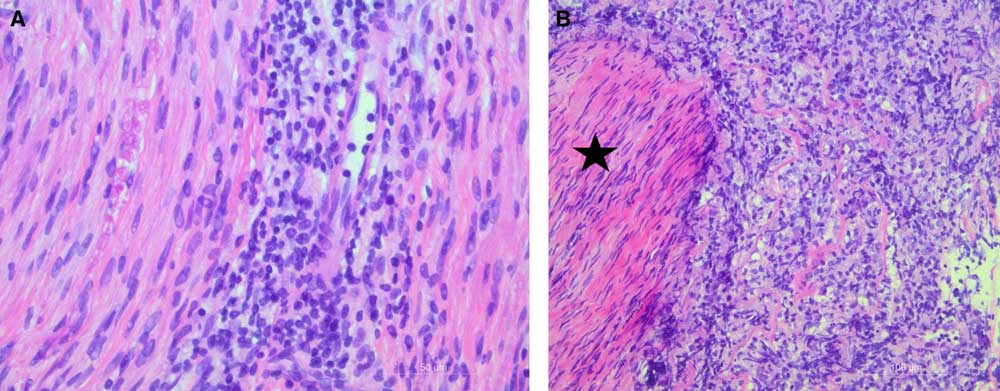

At surgical exploration, the left ulnar nerve was focally enlarged and discolored. There was no recognizable fascicular pattern when the epineurium was entered. Pathological examination showed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, with a non-germinal center phenotype (Figure 2). The patient was treated with combination chemotherapy (CHOP, rituximab) followed by adjuvant radiotherapy to the forearm (40 Gy in 15 fractions). There was relief of pain without recovery in ulnar nerve function, and the patient remained in remission from lymphoma when last assessed at age 80.

Figure 2 Case 1, biopsy of ulnar nerve. A: High power micrograph showing discrete lymphocytic infiltration within the endoneurium (40×objective lens, H&E stain). B: Lower power micrograph showing infiltrate of atypical large lymphocytes around a nerve fascicle (star) (20×objective lens, H&E stain).

Case 2

This patient had an unrelated past history of grade 2 diffuse astrocytoma of the right post-central gyrus, treated with cranial radiation and temozolomide at age 37. The only residual effect was partial epilepsy, well controlled with clobazam and levetiracetam.

At age 44, he noticed increasing stinging dysesthesia, as well as progressive numbness, on the lateral aspect of his right shoulder. This was associated with progressive asymmetric weakness of his upper limbs. There were no additional neurological or constitutional symptoms.

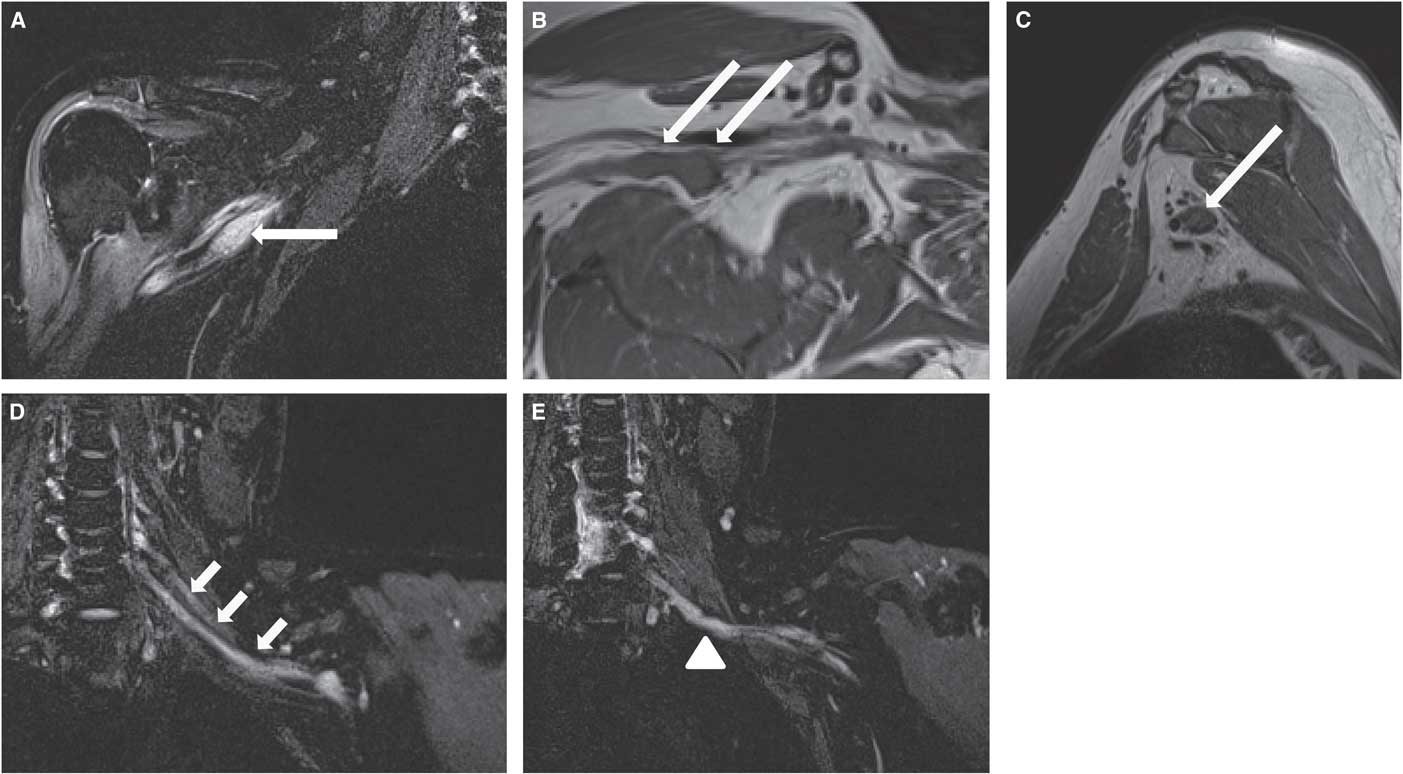

On examination, there was marked asymmetric weakness of both upper extremities. In the right upper limb, strength of most proximal muscles was graded 2/5, while hand intrinsic muscles were 4−/5. In the left upper limb, shoulder abduction was 4/5, but hand intrinsic muscles were graded only 2/5. Sensory testing was normal except for patchy hypoalgesia of the right forearm and hand. Upper limb reflexes were symmetrically reduced, graded 1+. Nerve conduction studies of the upper limbs were normal except for definite bilateral partial median nerve motor conduction blocks between Erb’s point and axilla. Needle electromyography (EMG) showed definite patchy, asymmetric active denervation and reinnervation in the deltoid, biceps, triceps and hand intrinsic muscles. MRI of the brachial plexuses showed bilateral irregular thickening of trunks and divisions bilaterally, with additional areas of focal nodular enlargement and enhancement (Figure 3). Enhanced MRI of the entire spine was negative. Extensive blood work as well as CSF analysis was normal. The initial diagnosis was a multifocal variant of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP).

Figure 3 Case 2. Coronal short tau inversion recovery STIR (A), axial oblique T1 (B) and sagittal T1W sequences (C) of the right brachial plexus demonstrate focal nodular thickening of the posterior cord (long arrows), with associated increased signal in the STIR sequence. Coronal STIR sequences (D, E) of the left brachial plexus show thickening of the visualized roots, trunks and divisions (short arrows), in particular of the lower trunk (arrowhead).

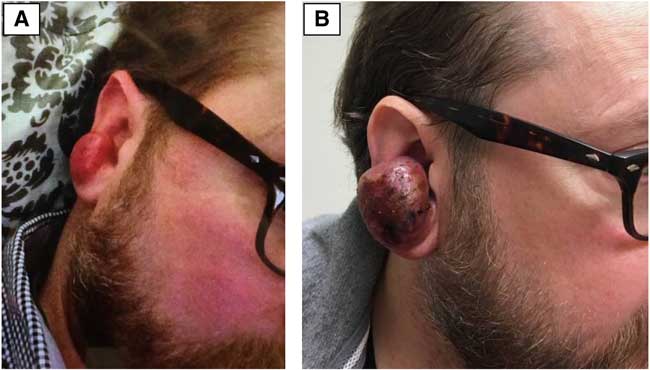

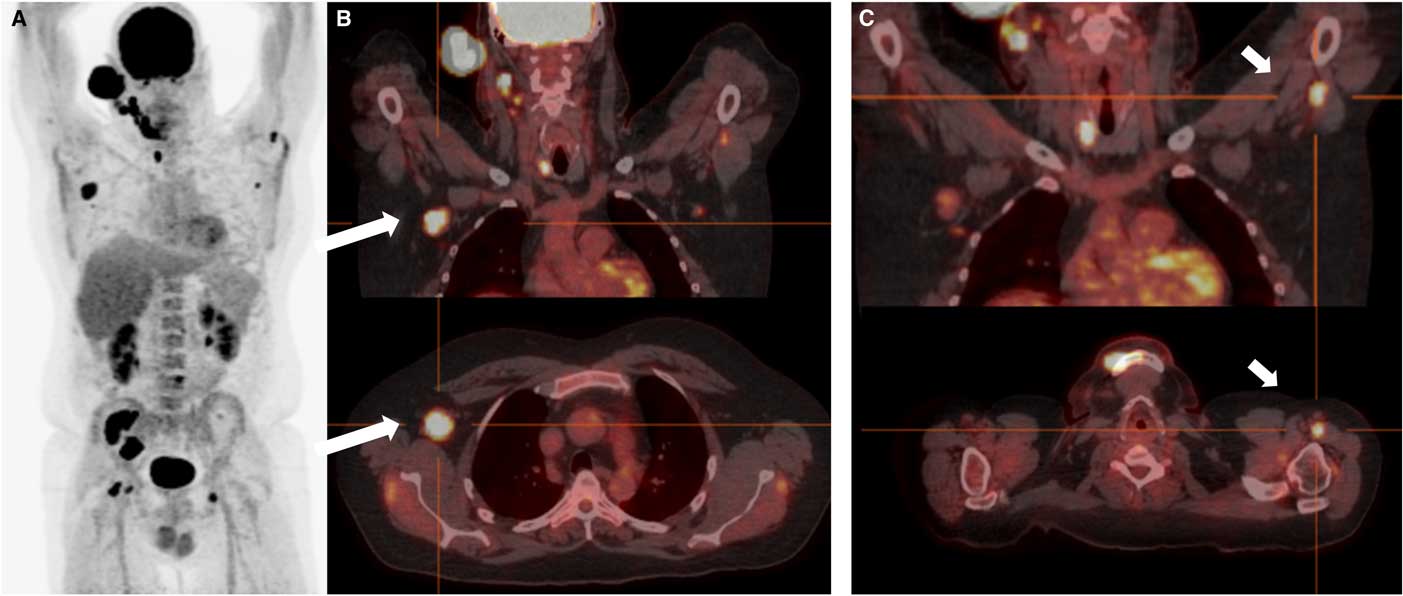

The patient was first treated with intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG). The response was equivocal, with improved strength of deltoid muscles, but worsening paresis of hand intrinsic muscles. Neuropathic pain in upper limbs also worsened, requiring treatment with narcotic analgesics. With the addition of Prednisone 60 mg daily there was initial marked clinical improvement, which was not sustained during the steroid taper. Eight months after clinical onset, the patient noted a small nodule over the tragus of his right ear, showing rapid expansion (Figure 4). Punch biopsies revealed a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, with ABC phenotype and anomalous CD5 expression. 18FDG-PET/CT showed very extensive multifocal pattern of lymphomatous involvement (ear, parotid region, neck, axilla and pelvis). There was an 1.0× 0.6 cm nodule along the left brachial plexus with a Standardized Uptake Value (SUV) of 6.3. Similarly, in the right axilla, intense focal uptake (SUV of 6.9) in a 3.0×2.2 cm soft tissue nodule corresponded to the brachial plexus thickening identified on MRI (Figure 5). The patient was started on R-CHOP chemotherapy, with an initial favorable response.

Figure 4 Case 2. Painless, rapidly expanding mass arising from the tragus of the right ear. This extranodal deposit led to the unexpected discovery of diffuse B-cell lymphoma. These two patient photographs (A, B) are separated by only 20 days. There was equally rapid regression of the tumor mass within 2 weeks of initiation of chemotherapy.

Figure 5 Case 2. A: Coronal 18FDG-PET showing widespread extranodal and nodal hypermetabolic foci. Note that intense uptake is a normal finding for the brain, optic nerves, kidneys and bladder. B and C: PET-CT fusion imaging in the coronal (top) and transverse (bottom) planes. There are areas of intense focal uptake at the level of the right axilla (long arrows) and distal left brachial plexus (short arrows ), in keeping with nodular neurolymphomatosis.

Case 3

This patient presented at age 62 with a testicular mass and widespread adenopathy from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. He achieved initial remission with seven cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy and testicular radiotherapy. He was also given prophylactic high-dose intravenous methotrexate. At age 66 he presented with recurrent inguinal lymphadenopathy. As additional radiotherapy and chemotherapy were ineffective, he was offered autologous stem cell bone marrow transplantation. At age 67 he presented with motor deficits in the left upper limb, initially localized to the hand intrinsic and finger flexor muscles (C8 myotome). There was moderate pain in the left scapular region, and only mild paresthesia on the ulnar border of the hand. Within a few months, more widespread paresis was noted, involving the left triceps (2/5), biceps (4−/5), and all hand intrinsic muscles. Electrodiagnostic studies showed a pattern of axonal loss and active denervation in keeping with marked left brachial plexopathy.

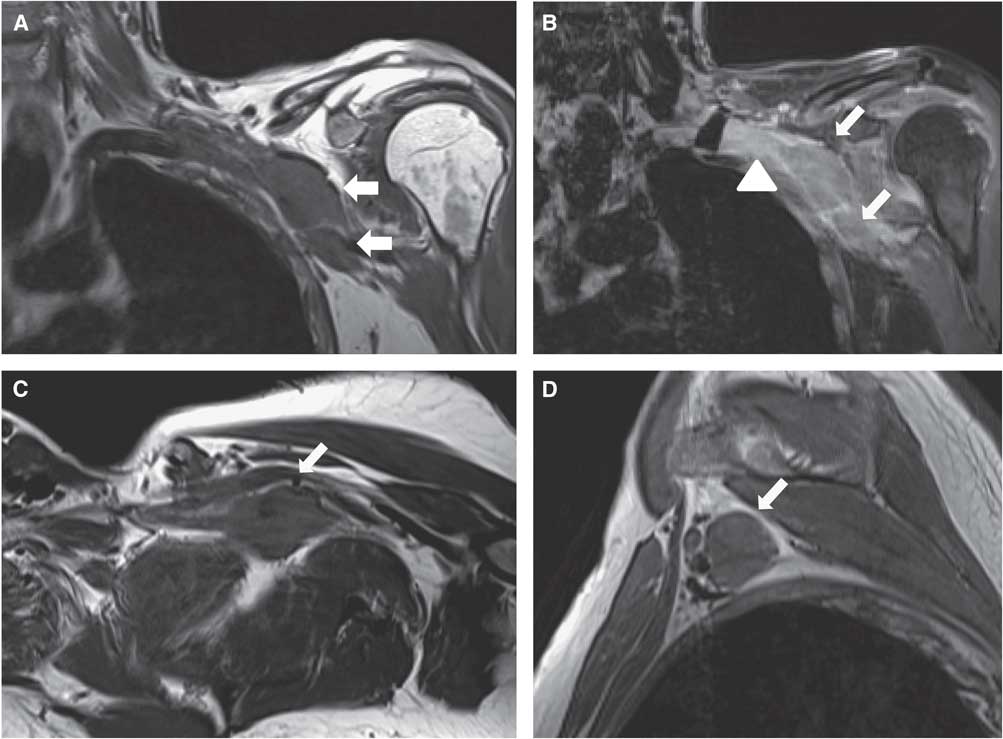

Enhanced MRI of the cervical spine and CSF examination were normal. MRI of the left brachial plexus showed two distinct soft tissue masses with avid gadolinium enhancement, infiltrating the left brachial plexus at the level of the divisions and cords (Figure 6). The patient was treated with supraclavicular radiotherapy (35 Gy in 10 fractions) but was unable to tolerate additional chemotherapy. He was referred to palliative care.

Figure 6 Case 3. Coronal T1 (A), coronal T1 with contrast and fat saturation (B), axial oblique T1 (C) and sagittal T1W sequences (D) of the left brachial plexus show focal masses (arrows) involving the distal cords and proximal branches. In addition, there is thickening, clumping and enhancement of the divisions (B) (arrowhead).

Discussion

Neurolymphomatosis is a rare condition, with a marked preponderance (90%) of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.Reference Grisariu, Avni, Batchelor, van den Bent, Bokstein and Schiff 5 Conversely, it is estimated that roughly 10% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma metastasize to peripheral nerves. In an autopsy series of 145 patients who died of lymphoma, some degree of peripheral nerve invasion was found in 40% of cases, though this particular series also included a large proportion of cases with leukemic conversion.Reference Jellinger and Radiaszkiewiez 6 In a literature review covering the period of 1973-2000, the diagnosis was only made at autopsy in 46% of cases.Reference Baehring, Damek, Maring, Betensky and Hochberg 7 Improvements in neuroimaging led to antemortem diagnosis in 95% and 98% in the two largest subsequent case series covering the period of 2001-2008.Reference Grisariu, Avni, Batchelor, van den Bent, Bokstein and Schiff 5 The incidence of NL is also felt to be increasing, though it is not known whether this reflects a bias of greater diagnostic recognition, longer survival from modern therapy, or a true selection of neurotropic clones of lymphoma cells. Neurolymphomatosis is notorious for presenting as a clinically isolated neuropathic syndrome, with a highly protean anatomical distribution.Reference Bower, McKelvie, Peppard and Roberts 8 This creates a diagnostic dilemma, particularly when neuropathy precedes the recognition of overt nodal or extranodal lymphomatous involvement.

Case 1 is an example of very focal upper limb NL, limited to a short segment of the ulnar nerve at the level of the proximal forearm. There have been few case reports of similar isolated involvement of the following distal branches of the brachial plexus: radial nerve (four cases),Reference Misdraji, Ino, Louis, Rosenberg, Chiocca and Harris 9 - Reference van Bolden, Kline, Garcia and vanBolden 12 median nerve (three cases)Reference Desta, O’Shaughnessy and Milling 13 - Reference Kim, Kim, Lee, Kang and Shim 15 and ulnar nerve (one case).Reference Teissier 16 With such mononeuropathies, at an anatomical location remote from common sites of entrapment, the initial differential diagnosis, in addition to NL, must include schwannoma, neurofibroma, hypertrophic neuritis, perineuroma, multifocal motor neuropathy and vasculitis.

Similarly, the trunks, divisions and cords of the brachial plexus may be involved in isolation as the first manifestation of NL.Reference Liang, Kay and Maisey 17 - Reference Choi, Shin and Kim 19 No specific anatomical distribution of brachial plexus involvement has been found to be characteristic of NL, in contrast to metastatic brachial plexopathy from breast or lung carcinoma (which commonly affects the lower trunk)Reference Iyer, Sanghvi and Merchant 20 , Reference Sureka, Cherian and Alexander 21 or radiation plexopathy (with a relative predilection for the upper trunk).Reference Jaeckle 22 , Reference Mondrup, Olsen, Pfeiffer and Rose 23 When there is no evidence of lymphoma on laboratory and imaging tests (CSF study, CT of thorax and abdomen, 18FDG-PET), surgical exploration and fascicular nerve biopsy may be necessary to reach a conclusive pathologic diagnosis. Nerve biopsy is, however, fraught with significant risk and morbidity, particularly at proximal sites such as the proximal plexus, spinal nerves or cranial nerves.Reference Grisariu, Avni, Batchelor, van den Bent, Bokstein and Schiff 5 Biopsy may be better justified at a distal limb location, or if there is already evidence of extensive axonal loss.

Case 2 illustrates the difficulty in distinguishing NL, which is a process of direct invasion of peripheral nerves, from paraneoplastic neuropathy, which covers a spectrum of remote, mostly immune-mediated demyelinating, neuronal or axonal disorders.Reference Graus, Arino and Dalmau 4 This patient had electrodiagnostic evidence of motor conduction block at the level of the brachial plexus, suggesting focal proximal demyelination, in keeping with the variant of CIDP known as multifocal acquired demyelinating motor and sensory neuropathy. MR imaging of the brachial plexus was first interpreted as in keeping with CIDP. This initial diagnostic conclusion was bolstered by temporary and partial improvement with both IVIG therapy and steroids. It was the appearance of a rapidly expanding lymphomatous deposit at the level of the external ear that led to the discovery and staging of systemic lymphoma with NL. 18FDG-PET was then the most conclusive imaging modality to document the distribution of lymphomatous spread.

The most common form of paraneoplastic neuropathy in lymphoma is a symmetrical demyelinating polyneuropathy, presenting rarely as Guillain-Barré syndrome or more commonly as CIDP.Reference Tomita, Koike and Kawagashira 18 , Reference Vallat, De Mascarel and Bordessoule 24 Other paraneoplastic peripheral nervous system (PNS) syndromes in lymphoma include rare cases of subacute motor neuronopathy,Reference Schold, Cho, Somasundaram and Posner 25 , Reference Flanagan, Sandroni, Pittock, Inwards and Jones 26 sensory neuronopathy,Reference Maslovsky, Volchek, Blumenthal, Ducach and LUgassy 27 , Reference Plante-Bordeneuve, Baudrimont, Gorin and Gherardi 28 and vasculitic neuropathy.Reference Zivkovic, Ascherman and Lacomis 29 , Reference Vincent, Gombert, Vital and Vital 30 With the exception of the infrequent vasculitic neuropathy and the initial stages of sensory neuronopathy, paraneoplastic neuropathy tends to be more diffuse and symmetric in distribution. In contrast, a majority of patients with NL present with an asymmetric multifocal or mononeuropathic pattern of sensorimotor deficits. Pain is more often moderately to severely disabling, though relatively painless focal or diffuse neuro-pathy is also well documented.Reference Baehring, Damek, Maring, Betensky and Hochberg 7

In the absence of pathological proof from CSF cytology, bone marrow aspiration, or biopsy of lymphadenopathy or extranodal disease, the distinction between NL and paraneoplastic neuropathy may be elusive. In a series of 32 patients with neuropathy associated with non-Hodgkin lymphoma,Reference Tomita, Koike and Kawagashira 18 it was possible to classify 15 cases as pathologically proven or 18FDG-PET positive NL and five cases as likely paraneoplastic. The remaining 12 patients could not be conclusively classified in either of these two categories based on radiological or pathological criteria.

MRI neurography features of NL include: nerve enlargement, isointensity to muscle on T1, hyperintensity on T2 or STIR sequences, fascicular disorganization and significant focal or diffuse gadolinium enhancement.Reference Chhabra, Andreisek and Soldatos 31 , Reference Thawait, Chaudhry and Thawait 32 There is, however, considerable overlap with findings expected in etiologies that are in the differential diagnosis of NL, such as inflammatory demyelination or radiation. In equivocal cases, imaging may suggest an appropriate target site for biopsy and definitive tissue diagnosis. Case 3 of our series demonstrates the difficulty in distinguishing extrinsic compression and encasement of the brachial plexus from a marked focal nodular proliferation arising from primary intraneural lymphomatosis. The presence of enhancement and enlargement of neighboring cords, divisions and trunks adjacent to a focal tumor mass suggest true intraneural spread, but a conclusive distinction is often not within the limits of resolution of the MRI.

In a series combining the Massachusetts General Hospital experience and a review of the literature up to the year 2000, and thus reflecting older MR technology, BaehringReference Baehring, Damek, Maring, Betensky and Hochberg 7 reported that only 28 of 40 (70%) cases of NL had documented nerve enlargement or enhancement on MRI. The diagnostic accuracy of MRI in NL improved to 28 of 35 cases (80%) in a more recent literature review covering the 2001-2008 period.Reference Grisariu, Avni, Batchelor, van den Bent, Bokstein and Schiff 5 In the three cases reported here, MRI played a key role in detecting lesions of the brachial plexus, though clinical context, ancillary studies and biopsy were required for a definitive diagnosis. In our case 2, the presence of large-diameter nodular enlargement of the brachial plexus likely pointed to NL rather than paraneoplastic inflammatory demyelinating neuropathy.

18FDG-PET/CT consistently reveals increased metabolic activity in the common aggressive lymphomas, with at least one 18FDG-avid lymphoma site detected in 100% for Hodgkin lymphoma and 97% for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.Reference Weiler-Sagie, Bushelev and Epelbaum 33 There are no large scale studies of 18FDG-PET in the specific setting of NL. In a series of 50 cases of NL reported by the International Primary CNS Lymphoma Collaborative Group, 18FDG-PET was positive in 16/19 (84%).Reference Grisariu, Avni, Batchelor, van den Bent, Bokstein and Schiff 5 These results may, however, mostly reflect the ability of PET to detect nodal or extranodal lymphoma in extraneural locations. Indeed, Case 2 demonstrates how 18FDG-PET may be better able to demonstrate hypermetabolism in nodular disease, with intense uptake demonstrated in these locations, and only mild asymmetry identified in regions of suspected infiltrative neural involvement. Although a post-therapy scan is not yet available for this patient, there are several articles demonstrating the use of 18FDG-PET to assess for treatment response in NL.Reference Lin, Kilanowska, Taper and Chu 34 - Reference Trojan, Jermann, Taverna and Hany 36

Survival rates for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma have been stratified according to the International Prognostic Index (IPI), which takes into account the patient’s age, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level, performance status, stage of distribution of adenopathy and presence of extranodal involvement. With modern chemotherapy regimens, the 3 year estimate for overall survival is in the range of 60% for the subgroup with highest IPI scores (4-5).Reference Ziepert, Hasenclever and Kuhnt 37 In contrast, GrisariuReference Grisariu, Avni, Batchelor, van den Bent, Bokstein and Schiff 5 reported a 36-month survival proportion of only 24% for patients with NL, though the majority showed an initial clinical and radiographic improvement with therapy. Radiotherapy has a limited role to control localized nerve involvement, particularly if there is disabling neuropathic pain, and systemic chemotherapy with rituximab and CHOP is the critical management option. High-dose IV MTX is often added. It has good penetration of the blood-brain and blood-nerve barriers, and may help prevent central nervous system relapses.Reference Lagarde, Tabouret and Matta 38

This case series exemplifies how brachial plexus involvement in NL is highly protean in its neuroanatomic distribution and clinical evolution. Neurolymphomatosis remains a diagnostic challenge, particularly in cases where it precedes overt lymphoma, or manifests after prolonged remission. The combination of dedicated MRI neurography and PET-CT has greatly improved diagnostic accuracy, though clinical acumen remains paramount.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial or other conflicts of interests relevant to this manuscript to disclose.

Statement of Authorship

PRB: identification of case series, data collection, project supervision, drafting and revision of manuscript. JWC: critical revision of manuscript. MB: selection and annotation of Figure 5 and discussion of the role of PET imaging in NL. Review of manuscript. MT: review of manuscript, with special emphasis on treatment of lymphoma. BFB: Preparation of Figure 2 and neuropathology discussion. CT: Selection and discussion of MRI imaging figures and legends, critical review of manuscript.