1. Introduction

This paper examines the relative effects of phonetic and phonological salience on the processing of high (H) versus low (L) tones. While there is evidence from many areas of the phonological literature that H tones are more salient than L tones (e.g., De Lacy Reference De Lacy1999, Reference De Lacy2002, Reference De Lacy2007; Harrison Reference Harrison1998; Riestenberg Reference Riestenberg2017), there are languages in which L tones can be shown to be more phonologically salient (e.g., Hyman Reference Hyman2001; Krauss Reference Krauss, Hargus and Rice2005; Jaker Reference Jaker2012). This paper addresses these two types of tone salience, investigating which effect best predicts tone processing patterns.

A tone recall task was carried out by speakers of French and Tłı̨chǫ, an endangered language of Canada in which L tones are phonologically prominent, as argued in §4.2. The results suggest evidence of a phonetic effect on tone recall among French speakers, whose phonology does not bias them towards either tone. There is also evidence of a phonological effect among Tłı̨chǫ speakers, for whom L tones were easier to recall than H tones.

The next section provides an overview of the relative salience of H and L tones, both from a phonetic and a phonological standpoint. §4 examines the phonetics and phonology of tone in Tłı̨chǫ, confirming both that F0 is a phonetic correlate to tone in this language, and that it is the L tones that are more phonologically prominent. §5 introduces the experiment carried out in this study, and §6 provides the results. In §7, the results are argued to show effects of both phonetics and phonology on tone processing. This section also discusses the benefits of conducting experimental linguistic work in a fieldwork setting. §8 concludes with a summary of the results and their implications.

2. Salience of H vs. L tones

As many as 60–70% of the world's languages use tone to convey lexical and grammatical contrast (Yip Reference Yip2002). These tonal languages exist across a diverse set of language families, including languages native to Africa, Europe, East Asia, and the Americas. Linguistic tones are distinguished by their pitch height and contours, the primary phonetic cue to which is fundamental frequency (F0)Footnote 1 (Gandour Reference Gandour and Fromkin1978; Yip Reference Yip2002). Evidence both from the theoretical phonological literature and from language acquisition studies suggests that tones with higher pitch targets (H tones) are more perceptually salient than those with lower pitch targets (L tones), but that L tones can nonetheless have more phonological prominence in the tonal systems of some languages.

2.1 Acoustic Salience of H tones

The notion of acoustic salience is often nebulously described, as there is no single acoustic correlate to salience. However, there is evidence from multiple areas of the phonological literature that argues for the relatively high acoustic salience of H tones without relying on purely acoustic data. For instance, there is a cross-linguistic tendency for metrical prominence and H tones to co-occur as a result of phonological processes, suggesting that H tones are inherently more prominent than lower tones (De Lacy Reference De Lacy1999, Reference De Lacy2007). One example comes from Golin (Trans-New Guinea, Papua New Guinea), in which stress falls on the rightmost H-toned syllable; in the absence of a H syllable in a word, stress defaults to the rightmost syllable of the word (De Lacy Reference De Lacy1999). Similarly, in Ayutla Mixtec (Mixtec, Mexico), metrical feet are attracted to the left edge of a word, unless a foot headed by a H, a ‘perfect toned foot,’ appears closer to the right edge (De Lacy Reference De Lacy2007). Based on this and other similar phonological phenomena involving the co-occurrence of high tone and metrical prominence, De Lacy (Reference De Lacy1999) posits a tonal prominence scale H > M > L. This scale operates similarly to the sonority hierarchy (Parker Reference Parker2002, Reference Parker, Hume, Oostendorp, Ewen and Rice2011), predicting how tones are likely to interact with each other in phonological processes. Though this argument for tonal prominence does not directly stem from the acoustic properties of the tone heights, there is a clear typological tendency for languages to develop with a bias towards H tones as more prominent than others.

In addition to this phonological evidence for the relative prominence of H tones, evidence from the speech perception literature shows a similar patterning. Among speakers of tone languages, it has been shown that contour tones are more easily perceived and identified than level tones (Yip Reference Yip2002; Francis et al. Reference Francis, Ciocca and Kei Chit Ng2003), suggesting that contour tones are the most psychoacoustically salient of all linguistic tone types (Mattock and Burnham Reference Mattock and Burnham2006). This is corroborated by Huang and Johnson (Reference Huang and Johnson2010), who show that Chinese speakers attend to pitch contours when discriminating among different tones. However, in the same study, American English speakers attended to pitch height to complete the same task; for these speakers, the easiest tones to distinguish were those with H versus L pitch targets. This is one of many studies showing that speakers of non-tone languages, whose phonology does not bias them towards one lexical tone over another, use pitch height rather than pitch contour to discriminate among lexical tones (Francis et al. Reference Francis, Ciocca and Kei Chit Ng2003; Riestenberg Reference Riestenberg2017). Other studies have shown that of tones with distinct pitch heights, H level tones were the easiest to perceive, followed by L or extra-L tones (see discussion in Yip Reference Yip2002).

A similar pattern of relative salience emerges from both the L1 and L2 acquisition literatures. Harrison (Reference Harrison1998) uses tone perception experiments to show that six- to eight-month-old babies acquiring Yoruba, a tone language, as their L1 discriminate H tones from other tones, but have a harder time distinguishing non-H tones from each other. This is in line with findings from adult speakers of non-tone languages, who are also best at distinguishing H tones from all other non-H tones (Harrison Reference Harrison1998). These perceptual patterns also have parallels in findings on L2 acquisition. A study examining the acquisition of lexical tone in San Pablo Macuiltianguis Zapotec (Zapotec, Mexico) finds that L2 learners may attend more to tones with higher pitch targets, and therefore acquire these tones more easily than tones with lower pitch targets (Riestenberg Reference Riestenberg2017). Overall, findings in theoretical phonology, non-native speech perception, and first and second language acquisition all suggest that among level tones, H tones are more perceptually salient than L tones.

2.2 L-markedness

Given the high perceptual salience of H tones relative to L tones, it is not surprising that most languages with a two-way tone contrast distinguish between underlying H and Ø (Hyman Reference Hyman2001). In these languages, syllables that surface as L are in fact grammatically unspecified for tone, and are simply produced with a lower pitch than the phonologically H tones. However, there also exist languages that exhibit a tone distinction between L and Ø (Hyman Reference Hyman2001, Reference Hyman2007). These two types of tone languages are referred to in the literature as H-marked and L-marked, respectively.Footnote 2 Tłı̨chǫ, an endangered and under-documented Northern Athabaskan Dene language spoken in the Northwest Territories, Canada, is an example of an L-marked language; L tones in Tłı̨chǫ are active in phonological processes, as demonstrated in §4, and H tones surface only on syllables that are unspecified for tone (Hyman Reference Hyman2001; Krauss Reference Krauss, Hargus and Rice2005; Jaker Reference Jaker2012).

3. The Present Study

The aim of this study is to determine whether the phonological status of L tones in Tłı̨chǫ makes them more perceptually salient to speakers of this language, despite the fact that H tones are said to be otherwise more acoustically salient. The study compares the tone processing of speakers of Tłı̨chǫ and French, a language with no tone distinctions. Though French does have syllables that are relatively more prominent than others, this prominence predictably falls on word-final syllables, and is cued by vowel duration and not F0. In fact, Dupoux et al. (Reference Dupoux, Pallier, Sebastian and Mehler1997) show that when asked to distinguish between nonce words that are segmentally identical but have different stress patterns, French speakers are less successful than speakers of Spanish, a language with contrastive stress. In the same study, when asked to determine whether words are segmentally identical, even if they have different stress patterns, French speakers were able to ignore the stress cues while Spanish speakers were not. Furthermore, though French speakers are able to perceive differences in F0 when listening for syllable stress, they do not rely on this F0 cue to determine stress placement (Frost Reference Frost2011). Therefore, if French speakers show differential processing between H and L tones, this result must be due to the different acoustic properties of the tones and not due to a bias from any phonological patterning in French. Tłı̨chǫ speakers, on the other hand, may be influenced by the phonological prominence of L tones in their language when processing speech sounds.

If H tones are processed more easily than L tones by all speakers, this will be evidence for a phonetic effect on processing, such that the relative acoustic salience of H and L tones best predicts how they are processed. If, on the other hand, Tłı̨chǫ speakers process L tones more easily than H tones, this will support the notion that the effects of phonological salience can override the effects of acoustic salience in tone processing.

4. Phonetics & Phonology of Tłı̨chǫ Low Tones

This study examines the perception of tone by speakers of Tłı̨chǫ (ISO 639-3 dgr).Footnote 3 The language is considered endangered and is currently spoken by around 2,000 people located between Great Slave Lake and Great Bear Lake in Canada's Northwest Territories.Footnote 4 The community is currently engaged in language revitalization efforts, including language instruction for younger members of the community who are mostly monolingual in Canadian English (e.g., Tłı̨chǫ Community Services Agency 2005).

The experiment carried out here, which examines the perception of high versus low tones, relies on two assumptions about the tonal system in Tłı̨chǫ. The first assumption is that F0 is an acoustic correlate to tone in this language. The predictions about acoustic salience of tone are only relevant if it is in fact F0 that is the main correlate to this contrast. The second assumption is that Tłı̨chǫ is in fact phonologically L-marked, as suggested in the typological literature (e.g., Hyman Reference Hyman2001) as well as in the literature on the phonology and morphosyntax of Dene languages (e.g., Saxon Reference Saxon1979; Krauss Reference Krauss, Hargus and Rice2005; Jaker Reference Jaker2012). The predictions about the relative phonological prominence of Tłı̨chǫ tones only hold if L tones in this language are in fact active and H tones surface by default on phonologically toneless syllables. This section provides phonetic (§4.1) and phonological (§4.2) evidence from Tłı̨chǫ, with the goal of motivating these two major assumptions.

4.1 Phonetics of Tłı̨chǫ Tone

Though tone in Tłı̨chǫ is often discussed in descriptive and analytical work on the language, no existing literature has examined the phonetic implementation of tone in Tłı̨chǫ. Since it is well-documented that there may be cues to phonological tone other than F0 (e.g., Morén and Zsiga Reference Morén and Zsiga2006; Yu and Lam Reference Yu and Lam2014), it is important to confirm that F0 does in fact correlate with the linguistic tone heights in Tłı̨chǫ. To this end, this section examines the acoustics of pitch in Tłı̨chǫ speech, confirming that F0 is a reliable cue to tone in this language.

Figures 1 and 2 show F0 in two representative examples of Tłı̨chǫ phrases of different prosodic lengths. Below the pitch tracks in these examples are transcriptions in the Tłı̨chǫ orthography, which employs a near-phonetic alphabet that marks low tones with grave accents and does not mark high tones. Per the conventions of the speaker community, captions contain the IPA transcriptions with L syllables marked with a grave accent and surface H tones are not marked. The examples come from Bible.is, an online mobile app that has text and audio versions of the Bible in over 1,300 languages, including Tłı̨chǫ.Footnote 5 The utterances shown here are both produced by the same native Tłı̨chǫ speaker, an adult female speaker who works as a translator and interpreter (Leslie Saxon, Nicholas Welch; personal communcation). Both of these phrases come from the recording of the Tłı̨chǫ translation of Luke 1:28.

Figure 1: Example of pitch on one multimorphemic word in Tłı̨chǫ (/hajèhti/; ‘he told her’)

Figure 2: Example of pitch on one intonational phrase in Tłı̨chǫ (/nexè shìɣà welè/; ‘peace be with you’)

Figure 1 provides an example of the pitch contour across one multimorphemic word in Tłı̨chǫ. The word has a HLH tone melody. The first syllable, a high-toned prefix, is produced with a mean F0 of 204 Hz. The subsequent low-toned syllable is produced with a mean F0 of 150 Hz, about 50 Hz lower than the preceding high tone. The final syllable in the word is another high tone, produced with a mean F0 of 184 Hz, about 30 Hz higher than the preceding low tone. The fact that the final high tone in the word is produced with an F0 that is 20 Hz lower than that of the initial high tone is in line with cross-linguistically common downdrift processes, in which high tones later in the phonological phrase tend to be produced with lower F0 than phrase-initial high tones.

Figure 2 shows an example of F0 on a longer intonational phrase in Tłı̨chǫ. The tone melody on this phrase is HL LL HL. The first syllable in this phrase is a high tone, produced with a mean F0 of 240 Hz. The following three syllables are low-toned syllables, each produced with a mean F0 between 160 and 170 Hz. The penultimate syllable is high-toned and is produced with a mean F0 of 201 Hz, which is 40 Hz above the previous low-toned syllable, though still 40 Hz lower than the initial high tone in the phrase. The final syllable in the phrase is low-toned, produced with a mean F0 of 159 Hz, effectively equal in pitch to the previous low tone in the phrase. Again, the low tones here are produced about 40–50 Hz lower than the initial high tone in the phrase, and high tones later in the phonological phrase, while higher than the nearby low tones, demonstrate phonetic downdrift.

Taken together, these representative examples show that F0 is in fact a phonetic correlate to phonological tone in Tłı̨chǫ. Syllables that are written as bearing low tone are consistently produced with an F0 about 50 Hz lower than preceding high tones. Tłı̨chǫ also exhibits phonetic downdrift, in which initial high tones in a phonological phrase are produced with the highest F0 of the phrase, and subsequent high tones are produced with progressively lower F0. This data does not preclude the presence of an additional perceptual cue to tone, such as vowel duration or voice quality cues, in the language. However, even if secondary cues to tone exist in Tłı̨chǫ, what is important to this study is that pitch is a reliable cue to tone.

4.2 Phonology of Tłı̨chǫ Low Tones

Tłı̨chǫ is frequently referred to in the Dene and typological literatures as an L-marked language, one in which low tones are phonologically active and high tones surface only in the absence of a low tone (e.g., Hyman Reference Hyman2001; Krauss Reference Krauss, Hargus and Rice2005; Jaker Reference Jaker2012). As discussed above, Tłı̨chǫ orthography encodes low tones with a grave accent, and does not mark high tones in the orthography at all. Though this orthographic convention may shed light on the phonological patterning of tone, and though it may bias literate Tłı̨chǫ speakers towards low over high tones in speech processing, it is not in and of itself evidence that Tłı̨chǫ is phonologically L-marked. Rather, this section provides three pieces of purely phonological evidence that together confirm the assumption that the low tone is the active tone in the Tłı̨chǫ phonology.

The first piece of evidence supporting the claim that Tłı̨chǫ is an L-marked language is that the tones in Tłı̨chǫ are opposite to those of neighboring H-marked Dene languages (Saxon Reference Saxon1979). This correspondence across neighboring Dene languages may be due to a historical tone reversal, in which phonologically active tones in Tłı̨chǫ were once high but became low tones, but retained their phonological status. Though this tone reversal process is typologically rare, Hyman (Reference Hyman2001) documents at least one other instance of this diachronic process, in this case the Bantu language Ruwund, and proposes a diachronic scenario by which tones were inverted and reanalyzed. On the other hand, it may be the case that glottalized vowels in Pre-Proto-Athabaskan and Proto-Athabaskan developed into a L-marked tone system in Tłı̨chǫ and into a H-marked tone system in neighboring varieties (Leer Reference Leer and Kaji1999, Reference Leer and Kaji2001; Krauss Reference Krauss, Hargus and Rice2005). Regardless of the historical origin of Tłı̨chǫ's synchronic tone system, the correspondence between low tones in Tłı̨chǫ and high tones in neighboring varieties lends support to the claim that Tłı̨chǫ has an L-marked tone system.

French borrowings into Tłı̨chǫ also provide evidence that low tones are the active tone in this language. In many H-marked Dene languages, French words are borrowed with a final high tone, corresponding to the French fixed word-final prominence, described above in §2. However, in Tłı̨chǫ, French borrowings have a final low tone (Krauss Reference Krauss, Hargus and Rice2005). In other words, the word-final prominence in the French word corresponds to a final L tone in Tłı̨chǫ, suggesting that the low tone is in fact the prominent tone in Tłı̨chǫ. For example, the word for ‘tea’ in Hare, an H-marked Dene language, is /lıdí/ (<le thé) and the word for ‘cotton’ is /lígodǫ́/ (<le coton) (Krauss Reference Krauss, Hargus and Rice2005). In Tłı̨chǫ, these words are borrowed as /lıdì/ and /lìgodǫ̀/, respectively, with final low tones (Krauss Reference Krauss, Hargus and Rice2005; Tłı̨chǫ Community Services Agency 2005). Though it is possible that these French words were borrowed into Tłı̨chǫ from a neighboring H-marked Dene language and not from French itself (see discussion in Prunet Reference Prunet1990), this pattern nonetheless provides evidence that the low tone in Tłı̨chǫ is the phonologically prominent tone.

The final piece of phonological evidence for Tłı̨chǫ's L-marked status comes from two synchronic morphophonological processes in the language. The first is a process involving the possessed noun suffix (PNS) in Tłı̨chǫ, as described by Saxon and Wilhelm (Reference Saxon and Wilhelm2016). In Tłı̨chǫ, the PNS surfaces on nouns in possessive and other morphologically similar constructions. This suffix usually surfaces as an additional mora which copies the features of the preceding vowel and bears a low tone (1).

However, this PNS is in some cases exponed by a floating low tone, as in the examples in (2). In all four of these examples, a final toneless syllable, which is produced with a high tone when the word appears in isolation, associates with the floating low tone and the syllable consequently surfaces with a low tone. Crucially, unlike in the examples in (1), no additional mora is being added here; rather, the L tone is the sole exponent of the PNS morpheme and is added to the existing moras in the noun phrase (Saxon and Wilhelm Reference Saxon and Wilhelm2016). The unaffixed form of each noun in (2) is italicized, showing that the final L tone in each case is the PNS morpheme and does not surface on these nouns otherwise (Saxon and Siemens Reference Saxon and Siemens1996).

The evidence of a floating low tone in (2) provides strong support for the notion that the low tone in Tłı̨chǫ is phonologically marked. In order for a tone to be present underlyingly without being borne by a tone-bearing unit, low tones must be phonological units that are active in phonological processes. The fact that these low tones surface on syllables that would otherwise be produced with a high tone suggests that the high tone is not present in the underlying representation and rather surfaces by default only in the absence of a low tone. In addition, there are no equivalent phonological processes in Tłı̨chǫ in which a high tone is the sole exponent of a morpheme and surfaces on an otherwise L syllable (Keren Rice, personal communication); that is, there are no processes in which the high tone is active in the Tłı̨chǫ phonology or morphophonology.

The second morphophonological process that supports the notion that Tłı̨chǫ is L-marked involves tones that surface on coalesced vowels (see discussion in Jaker Reference Jaker2012). In some morphophonological contexts, two adjacent vowels in the input surface as a single short vowel. In cases where one of the input vowels would otherwise surface as H and the other as L, the output short vowel always surfaces with a L tone (3).Footnote 7 This process is demonstrated in (3) (Jaker Reference Jaker2012; glosses from source).

Though Jaker (Reference Jaker2012: 435) formalizes this process as a H-deletion rule by which H tones are deleted if they are associated to the same mora as a L tone, the facts support a system in which L tones associate to otherwise toneless moras, so that both /H L/ and /L H/ sequences on consecutive moras surface as L when there is only one mora in the output form.

Evidence from Dene typology and historical phonology, French borrowings in Dene, and Tłı̨chǫ morphophonological alternations together provide a convincing argument that Tłı̨chǫ is in fact an L-marked language, supporting the second assumption relevant to this study. L tones in Tłı̨chǫ are associated with prominence and are active in the phonology, whereas high tones surface by default in the absence of a low tone.

5. Methods

This section details the recall experiment conducted with the aim of determining the relative effects of phonetic and phonological salience in the processing of tone by French and Tłı̨chǫ speakers.

5.1 Participants

The participants in this study were 17 native speakers of French and 14 native speakers of Tłı̨chǫ, all over the age of 18. French speakers were recruited through the principal investigator's professional network, and Tłı̨chǫ speakers were recruited and participated in Canada's Northwest Territories. All participants in this study were also proficient in a North American variety of English.

5.2 Materials

The stimuli in this experiment were sequences of six CV syllables. The segmental inventory from which the syllables were generated was /p t s i u a/, all of which correspond to surface variants in both languages. Only voiceless consonants were used here, as voiced consonants have been shown to interact with F0, both phonetically and, in many languages, phonologically (Yip Reference Yip2002). The nine syllables generated from this segmental inventory were produced by a native Thai speaker as nonce syllables. Each syllable was produced five times: once with each of the five Thai lexical tones (low, mid, high, falling, and rising). The L and HFootnote 8 level tones were extracted from the resulting recording and used to generate the sequences tested here. One L pitch track and one H pitch track from the recording were extracted and each resynthesized onto the M tone production of the Thai speaker in Praat (Boersma and Weenink Reference Boersma and Weenink2017). There were four resulting recordings for each of the syllables: one natural L production, one natural H production, one production resynthesized with the L contour, and one production resynthesized with the H contour.

Stimulus sequences contained syllables produced with either H or L tones; there were at least two H syllables and at least two L syllables, in varying orders, in each sequence. There were no more than two consecutive syllables hosting the same tone in any stimulus sequence, and all of the H- and L-toned syllables in the sequences were those naturally produced by the Thai speaker. Stimulus syllables were separated by approximately 300 ms of silence. Each stimulus sequence was followed by a test syllable. This test syllable either matched one of the syllables in the stimulus sequence or did not match any of the stimulus syllables. Matching test syllables were segmentally and tonally identical to one of the syllables in the sequence, but were the resynthesized version of the given syllable; as a result, they were acoustically distinct from the syllable they matched. This acoustic difference between the syllable and its match meant that participants were tasked with remembering the segmental information of a syllable and not merely the acoustic details of the utterance. Examples of trials with a matching high-toned syllable (4-a), a matching low-toned (4-b), and with no matching syllable in the previous sequence (4-c) are provided below.

Non-matching test syllables were segmentally different from each of the syllables in the stimulus sequence, i.e., there were no trials in which, for example, /tà/ appeared in the stimulus sequence and /tá/ was the test syllable. The purpose of the test syllable methodology was to avoid a more common type of recall experiment, in which participants are asked to repeat stimulus syllables (e.g., Crowder Reference Crowder1971; Kissling Reference Kissling2012; Barzilai Reference Barzilai2019). With this type of experiment, it would have been necessary to measure the tones of the responses, which not only would have created a methodological challenge of determining the tone of reproduced syllables, but would also have required French speakers to accurately reproduce H and L tones. Given that French does not use tone for any linguistic contrast, this would have biased the results in favor of the Tłı̨chǫ speakers, and likely would have obscured any actual perceptual effects of the stimulus tones. The test syllable methodology, on the other hand, tests for the perceptual effects of tones without requiring that participants correctly reproduce tones. Rather, what is being tested here is whether the tone of a stimulus syllable and its corresponding test syllable impacts the rates at which the segmental material of the syllables are remembered.

5.3 Procedure

The experiment was run on a laptop computer using PsychoPy (Peirce Reference Peirce2007). French speakers participated in the experiment in a sound-attenuated booth; Tłı̨chǫ speakers participated in the experiment in a quiet office in the Tłı̨chǫ government offices in Behchokǫ̀, Northwest Territories, Canada.

The experiment conducted in this study used a modified immediate serial recall (ISR) methodology, adapted from previous work that uses ISR results to argue for the differential processing of different speech sound types (see, e.g., Crowder Reference Crowder1971; Kissling Reference Kissling2012; Barzilai Reference Barzilai2019 on differential processing of consonants and vowels in ISR.)

Stimulus sequences were presented auditorily on a laptop computer; test syllables played approximately 1500 ms after the end of the stimulus sequence. The participants were told that their task was to determine whether the test syllable they heard was the same as one of the syllables they heard in the sequence or not. No mention of tone was included in the instructions. The right and left arrows on the computer keyboard were used as the response keys; the key corresponding to a matching syllable was counterbalanced across participants. All sequences were randomized for each participant. There were three practice sequences before the beginning of the actual testing portion of the experiment, and the principal investigator remained in the room during this practice session in case the participants requested clarification. None of the practice sequences was repeated during the remainder of the experiment.

Keyboard responses were recorded automatically and coded for accuracy for each target syllable tone. A mixed-effects logistic regression model was fit to predict mean score based on speaker L1 and target tone.

6. Results

An initial examination of the data revealed that one of the native Tłı̨chǫ speakers produced the same response for all trials in this experiment, suggesting that they did not understand the task; this person was removed from the analysis. Similarly, one participant failed to give a response for over 15 of the trials in this experiment and therefore was also removed. The results below are from the remaining speakers.

Table 1 shows the mean scores in this experiment by participant L1 and target syllable tone.

Table 1: Mean correct response (standard error) by L1 and target syllable tone

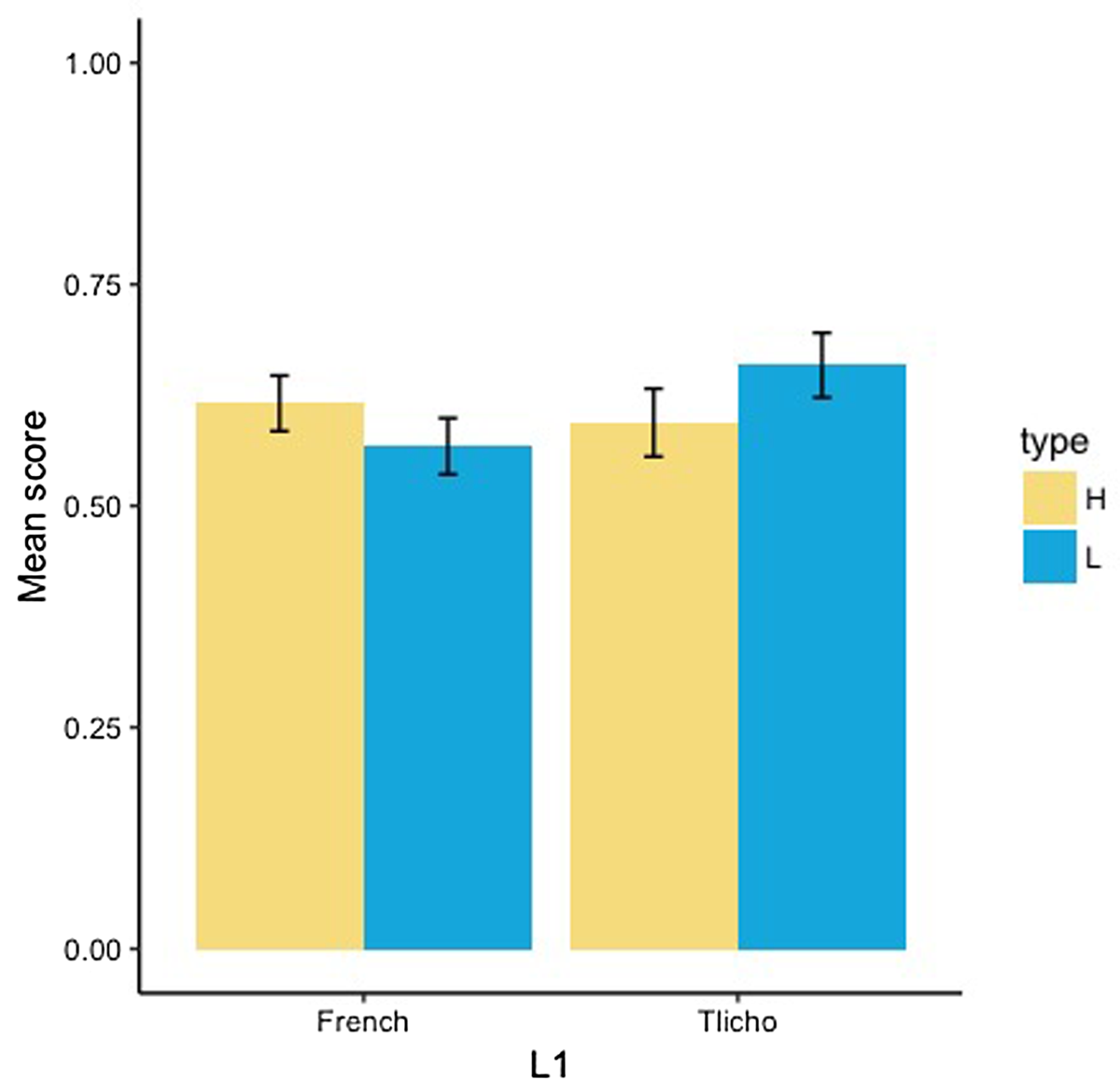

Figure 3 shows the mean recall scores. Both groups had a mean accuracy of approximately 0.60 when recalling H syllables. Within the groups, French speakers had a lower mean score when recalling L syllables, whereas Tłı̨chǫ speakers had higher mean scores when recalling L syllables.

Figure 3: Recall scores (standard error) by L1 and target syllable tone

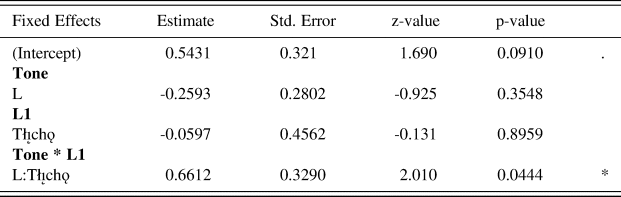

A mixed-effects logistic regression model was fit using the glmer function in the lme4 R package (Bates et al. Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015) to predict mean score on this task (Table 2). No significant main effect of target syllable tone was found, showing that neither tone was easier to recall for all participants. Similarly, no main effect of L1 was found, suggesting that speakers of both languages performed equally well on this task overall.

Table 2: Mixed-effects logistic regression model: recall accuracy. French as reference level for L1; H as reference level for target syllable tone. Speaker and syllable sequence as random effects.

However, the interaction between target syllable tone and L1 was significant (p = 0.0444); the relative means of H and L accuracy was significantly different for Tłı̨chǫ speakers than for French speakers. Though the pairwise comparison revealed no significant difference between recall rates for H versus L tones for the French speakers (p = 0.768) or for Tłı̨chǫ speakers (p = 0.563), this significant interaction implies that the relationship between H tone recall and L tone recall was significantly different across the L1 groups. The pairwise comparison also shows that in recalling H tone syllables, the two groups performed equally well (p = 0.999).

7. Discussion

The data presented in §6 shows opposite patterns across the two language groups: whereas French speakers remembered H tones slightly better than L tones, though this difference within the French group did not reach significance, the opposite was true for Tłı̨chǫ speakers. This pattern is analyzed here as the presence of both a phonetic and a phonological effect on tone processing. Implications of these results on the notion of acoustic salience, as well as suggestions about what these findings might mean for tone processing by speakers of other Dene languages, are also discussed in §7.1. Following a discussion of these effects, §7.2 addresses the challenges associated with collecting experimental data in a fieldwork setting and argues that these challenges are outweighed by the benefits.

7.1 Phonetic & Phonological Effects

These results presented in §6 are consistent with the presence of a phonetic effect in the relative processing of H and L tones. The difference between H and L recall by the French speakers fails to reach significance, showing that for speakers of a language that does not employ F0 for any linguistic contrast, the acoustic differences between H and L are not enough to impact recall. However, the fact that the French and Tłı̨chǫ speakers remembered H syllables with effectively equal accuracy supports the notion that acoustic salience is similarly active for both speakers in this task. In other words, the acoustic salience of H tones is such that speakers of both languages remember them equally well. This finding adds to the literature on acoustic salience of H tones (e.g., De Lacy Reference De Lacy1999, Reference De Lacy2007; Harrison Reference Harrison1998; Riestenberg Reference Riestenberg2017), showing that the properties of H tones that lead to their recall must be phonetic–that is, not related to any language-specific phonological properties—as speakers of phonologically distinct languages appear to be equally influenced by them.

Given the language-independent phonetic effect that facilitates processing of H over L tones, the difference between the two speaker groups shown in §6 comes from the fact that Tłı̨chǫ speakers are impacted by an additional effect of the phonological prominence of L tones, which boosts their recall. The statistical significance of the interaction between L1 and tone type shows that the L1 of the speaker influences the relative rates at which H and L tones are remembered. Specifically, whereas French speakers remembered H and L tones with effectively equal accuracy, the significant interaction between target syllable tone and L1 shows that Tłı̨chǫ speakers process the two tone levels at different rates from the French speakers. In other words, the phonological prominence of L tones in Tłı̨chǫ facilitates recall of L tones by speakers of this language, making for a different pattern than for speakers of French, which does not have grammatical tone and does not make use of F0 in any portion of the phonological grammar.

The phonetic and phonological effects in this study are in opposition, with phonetic salience facilitating H tone processing and phonological salience in Tłı̨chǫ facilitating L tone processing. However, as discussed above, most two-tone languages exhibit a contrast between H and Ø (Hyman Reference Hyman2001); the majority of Dene languages surrounding the region in which Tłı̨chǫ is spoken fall into this category (Jaker Reference Jaker2012). In these H-marked languages, the phonological effect would facilitate H tone processing. In other words, in H-marked Dene languages, the effects of phonetic salience and phonological salience both independently facilitate H tones over L tones. For speakers of these languages, future work could show how phonetic and phonological effects interact when they are not in conflict but rather simultaneously facilitate the same speech sound. It may be the case that the phonological effect of H tone prominence works with the effect of phonetic salience to create a compounded effect, such that these speakers show even higher rates of H tone recall than seen among French speakers. On the other hand, there may be a ceiling effect for these relative recall rates, such that the presence of a phonological effect in addition to the phonetic effect does not increase the rates at which H tones are recalled better than L tones.

It is worth noting that the relative effects of phonetic and phonological salience may be dependent not only on the phonetic and phonological patterning of the sounds in question, but also on the psycholinguistic task being carried out. Previous work on these effects provides evidence that while some tasks show only effects of phonetic salience, other tasks are more likely to show evidence of a phonological effect (Barzilai, Reference Barzilai2020). In this work, phonetic effects tended to arise with recall tasks that involved shorter-term processing than the task carried out here. On the other hand, phonological effects arose when the tasks required longer-term processing as well as explicitly phonological learning, such as in the case of an artificial language learning task in which speakers were asked to associate words in an artificial language with specific images. Overall, it may be the case the phonological effect evident here emerges in part as a result of the task being carried out, and that results from other types of processing tasks would show different relative strengths of the phonetic and phonological effects in question. Crucially, the fact that these effects are both observable and separable in experimental results shows that phonetic and phonological processing are distinct processing mechanisms.

7.2 Experimental Linguistics in the Field

The experiment in this study was carried out in part through linguistic fieldwork conducted in Behchokǫ̀, a remote village outside of Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada. Though experimental phonetics and phonology research has been conducted in the field, and even examining Athabaskan languages (e.g., Wright et al. Reference Wright, Hargus and Davis2002; McDonough Reference McDonough2003; Hargus Reference Hargus2016), the majority of experimental work, especially experiments investigating phonetic and phonological processing, does not include data from speakers of languages that are currently undergoing documentation efforts (Sande and Oakley Reference Sande and Oakley2019). As a result, languages that are otherwise under-represented in the literature are especially under-represented in linguistic work examining linguistic processing such as the study presented here.

As referenced in §6, there are some clear challenges associated with conducting experimental research in the field. Data from two Tłı̨chǫ speakers was removed due to evidence that the participant did not understand the task, or simply because the participant did not complete most of the task. The resulting low sample size of Tłı̨chǫ speakers likely contributes to overall low statistical power in the model generated from the data.

Not only was the overall number of Tłı̨chǫ speakers low, but there were other clear differences between the Tłı̨chǫ speakers and the French speakers in this study that may have generated experimental confounds. Many of the Tłı̨chǫ speakers who participated in this study expressed that they were not familiar with laptop computers such as the one on which the study was conducted. Though information about each participant's educational background was not explicitly collected for the purposes of this study, general demographic information about the Tłı̨chǫ community in Behchokǫ̀, where the data was collected, suggests that the Tłı̨chǫ-speaking participants in this this study had likely received far less formal education than the French speakers. It is possible, then, that the abstract nature of the linguistic task carried out in this study was more foreign to, and therefore more difficult for, the Tłı̨chǫ speakers than the French speakers.

Finally, some Tłı̨chǫ speakers who participated in this study mentioned having had some experience, direct or indirect, with linguists conducting fieldwork on the language. Crucially, the linguistic fieldwork that these speakers had experienced was elicitation-based language documentation and linguistic analysis; the speakers may quite logically have anticipated that participation in this study would involve Tłı̨chǫ elicitations and translations, not experiments requiring recall of nonce syllables. It is possible that this expectation, though reasonable given the nature of most previous linguistic fieldwork conducted with the Tłı̨chǫ community, created an additional hurdle for Tłı̨chǫ speakers when interpreting the instructions for the task.

Despite the methodological challenges associated with the collection of the data presented here, the experiment in this study reveals clear patterns in the processing of tones by the speakers examined, as well as presenting areas for a deeper understanding of the effect of an L-marked grammar on speakers’ tone processing. Therefore, in addition to its experimental findings, this study adds to the relatively small body of experimental phonetics and phonology literature specifically examining languages that are endangered, under-documented, or otherwise traditionally difficult to access. Without more inclusion of such data in the literature, the field's understanding of speech processing is inherently skewed.

8. Conclusion

This study provides evidence for both phonetic and phonological effects in the processing of high versus low tones. It is shown that for speakers whose phonology does not create a bias for either tone height, H tones are more easily processed. On the other hand, for speakers whose phonology biases L tones over H tones, it is these L tones that are more easily processed. In arriving at these results, this paper also provides a synthesis of the phonetic and phonological facts of tone in Tłı̨chǫ, showing that F0 is a cue to the contrast, and that L tones are the phonologically active tone in this language. The results have implications for the relationship between phonetic and phonological processing as well as for the general notion of acoustic salience. By including data from an under-represented language resulting from experimental fieldwork, this paper also argues for the continuation of work of this kind, as the contributions to the literature made by these results are outweighed by the challenges associated with obtaining data of this nature.