INTRODUCTION

Competency-based medical education (CBME) is a form of outcomes-based education for the health professions.Reference McGaghie, Miller, Sajid and Telder1 In the North American postgraduate medical education context, it has come to fruition with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Milestones Project and the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada's (RCPSC) Competence by Design (CBD) program.

For many years, medical educators have sought to define and measure the impact of education on clinical outcomes. Outcomes measurement is particularly important in CBME, because accountability is the cornerstone of its value as an educational framework.Reference Gruppen, Frank and Lockyer2 Specifically, outcome measurement for CBME is required to: (1) demonstrate the desired impact on physician training, (2) ensure that no harm is being done by means of unanticipated consequences of the initiative, (3) investigate concerns raised in the community about the need to justify the significant investment of resources, (4) determine what aspects of CBME components and implementations were and were not effective, and (5) determine contextual elements that lead to the resultant outcomes.Reference Gruppen, Frank and Lockyer2,Reference Holmboe, Sherbino, Englander, Snell and Frank3 In this study, we sought to define both educational and clinical outcomes within EM through a consensus conference.

Assembling an expansive collection of outcomes that include educational as well as clinical outcomes is of the utmost importance.Reference Touchie and Ten Cate4,Reference Ross, Hauer and van Melle5 Selecting outcomes that are purely patient-centered suffers from several key limitations, including problems with study feasibility, biased outcome selection, difficulty in attributing outcomes to learners, and inadvertently de-emphasizing other important skills.Reference Cook and West6–Reference Smirnova, Sebok-Syer and Chahine8 Our broad set of outcomes include factors such as learner supervision and resident cognitive load that consider the effects of supervision and context on resident performance, which aligns with current literature on the complexity of isolating trainee performance.Reference Smirnova, Sebok-Syer and Chahine8,Reference Sebok-Syer, Chahine, Watling, Goldszmidt, Cristancho and Lingard9 Residency is a decisive period in which to examine trainee performance as it encompasses a critical inflection point toward ultimate skill attainment. Therefore, as we transition to CBME, it is important to define and measure these outcomes to help residents along the path to both competence and mastery.

The implementation of CBD in Canadian EM in July of 2018 presents us with an opportunity to examine its outcomes. Evaluation of educational and clinical outcomes that arise from this new training model represents a direct form of accountability for the resources spent upon its design and implementation. As a detailed list of anticipated outcomes was not defined during the design of CBD, we aimed to use a consensus conference process to define a list of educational and clinical outcomes that EM training programs can reference when assessing implementation success.

METHODS

We conducted a three-phase (divergent, analysis, and convergent phase) study to solicit opinions from the emergency medicine community on important educational and clinical outcomes related to CBME that should be measured. The divergent phase consisted of a structured expert consultation process to generate an elaborative list of possible outcomes. The results from the divergent phase were then analyzed by our study team by means of a generic thematic analysis that resulted in the development of lists of clinical and educational outcomes. We presented this list of outcomes at the 2019 Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP) Academic Symposium where they were stratified by their level of endorsement.

Conceptual framework

Outcomes were conceptualized as being at the micro (resident, patient), meso (program, institution or region), or macro (system) level and being either clinical or educational in nature. In the Fall of 2018, we reviewed key medical education literature related to measurable outcomes of CBME. Our review strategy consisted of a structured Google Scholar search augmented by an open social media request for suggestions from experts in the medical education (#MedEd) community on Twitter.

Survey development

We developed a survey-based tool with the goal of soliciting diverse perspectives on potential clinical and educational outcomes for CBME. The survey consisted of three discrete parts: Part 1, open free-text suggestions of outcomes in the clinical and educational domains; Part 2, vignette-based brainstorming exercise; Part 3, open free-text entry for new or final thoughts.

Part 2 provided participants with three vignettes which situated emergency residents in different stages of training and clinical environments. Participants were asked to read the vignettes and then respond to questions designed to identify potentially measurable clinical and educational outcomes at the learner (micro), institutional (meso), and health system (macro) levels. The vignettes and the survey are presented in Appendix 1. The survey was developed and piloted internally by our study team before deployment. The vignettes were edited for clarity, readability, and appropriateness based upon feedback from the pilot.

Survey deployment

The survey was sent to 175 people, including EM Program Directors; CBD Implementation Leads; Competence Committee Chairs; Chief Residents from the EM training programs of both the RCPSC and the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC); one resident in addition to the Chief Resident at each program site; hand-selected physician leaders in administration, medical education, and quality improvement; Deans; Postgraduate leads; and international and national experts in the field of medical education. Participants were sent one initial email and two reminder emails spaced approximately 2 weeks apart.

Analysis of survey results

Upon survey completion, data were qualitatively analyzed by the authorship team (F.Z., Q.S.P., A.H., B.T., T.C.) and themes were generated within the education and clinical outcome spheres. All coding was reviewed by at least three authors with B.T. and T.C. reviewing all codes. B.T. and T.C. then summarized the content of each theme into outcome statements.

Convergent phase: academic symposium voting

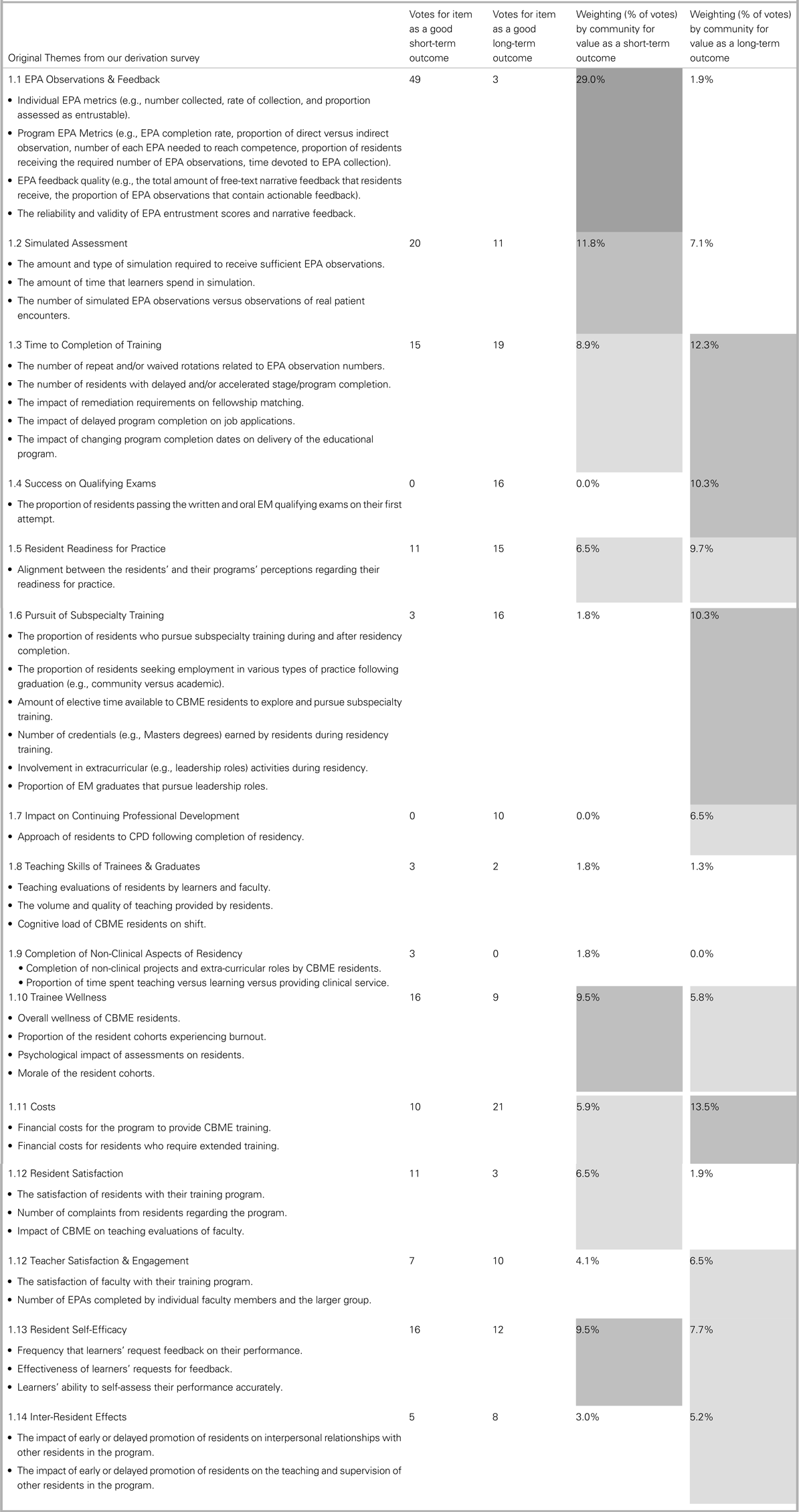

The list of outcomes was presented at the CAEP Academic Symposium on posters that organized the items based on the themes from our thematic analysis. Attendees were given stickers and tasked to vote upon the educational and clinical outcomes that they believed were: (a) most feasible to measure in the immediate (short-term) postimplementation period; and (b) most important to measure in the long-term period.

Participants were instructed to place stickers next to each outcome to represent the weight of their endorsement. The number of stickers next to each outcome were tabulated on site, and the results were presented to the audience at the end of the consensus conference session.

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS

A total of 30 individuals (17.1% response rate) completed our survey. Respondents included representatives from all the targeted groups (see Table 1). The results of the qualitative analysis are outlined in Table 2 (Educational Outcomes) and Table 3 (Clinical Outcomes). Box 1 details the recommendations that were most heavily favored during our symposium process.

Table 1. Demographics of survey respondents, n (%)

CAEP = Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians; CFPC = College of Family Physicians of Canada; EM = Emergency Medicine; MD = Medical Doctor; PhD = Doctor of Philosophy; RCPSC = Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada

*Since individuals might hold several roles or certifications simultaneously, the numbers in the sections will add up to more than 100%.

Table 2. Symposium educational outcomes

Table 3. Symposium Clinical Outcomes

Legend for abbreviations: CBME = Competency-Based Medical Education; ED = Emergency Department; $ = money

Box 1. Initial outcomes that should be measured in the early phase of CBME rollout most endorsed by the participants of the 2019 Academic Symposium

Summary of short-term outcomes

1. Outcomes at the micro- & meso-level

There are several short-term outcomes that could serve as easy, measurable outcomes to demonstrate the value of CBME. For instance, many educators endorsed measuring the number of entrustable professional activities (EPAs) observations and determining the quality of feedback. Previous studies on workplace-based assessment systems, such as In-Training Evaluation Reports (ITERs) have shown that examining the artifacts generated in a systematic way can improve the overall quality of assessment data.Reference Chan and Sherbino10

Going forward, it may be prudent for educators to form chains of evidence linking these immediately measurable outcomes (e.g., EPAs acquired during the first year) and later outcomes (e.g., likelihood of remediation required,Reference Ross, Binczyk and Hamza11 likelihood of completing areas of specific enhanced competency).Reference Binczyk, Babenko, Schipper and Ross12 Program leaders might harness the power of ongoing program evaluation or quality improvement, and that under our national research ethics policy (Tri-council Policy Statement 2),13 these efforts are usually deemed exempt from research ethics processes. As such, measuring the more accessible and top-rated short-term outcomes is both necessary and pragmatic for robust program improvement.

2. Wellness and trainee efficacy

Trainee wellness and resident self-efficacy were ranked in the top five educational outcomes to be measured in the short term, which aligns well with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement's Quadruple Aim. We might aim to determine if we are training of physicians committed to continuing professional development, and who are receptive to feedback and adept in providing it. Poor faculty feedback to trainees has been cited as a contributing factor to depression in trainees,Reference Pereira-Lima, Gupta, Guille and Sen14 whereas improved feedback has the potential to foster a sense of competence, autonomy, and relatedness.Reference Sargeant15 Because CBME advocates for an increase in the direct observation and provision of objective, high-quality feedback, program evaluators should attempt to study their effects on learner well-being.

3. Macro-level outcomes

Patient safety and quality of care metrics (e.g., evidence-based practice, efficiency and effects on hospital flow) for CBME trainees was one of the clinical outcomes that was ranked as most important to follow both in the short-term and the long-term. From a practical perspective, this appears daunting both in terms of data gathering and in establishing causal links between specific clinical outcomes and care provided. Collaboration between educators and quality improvement researchers will be essential to examine these complex systems. Other clinical outcomes, such as multi-source assessments for CBME residents in the clinical settings are more easily trackable and can provide useful information especially when linked to the educational outcomes of individual EPA metrics.

Summary of long-term outcomes

1. Health systems impact

Postgraduate training programs should focus on the endorsed long-term educational outcomes, as they sit in the broader health care system where budgets and human health resource management are important. Specifically, one of the most endorsed long-term educational impacts might be a change in the number of trainees pursuing sub-specialty training after their qualifying exams. Traditionally, the RCPSC training programs in EM have had an embedded area of focused learning that was part of the Postgraduate year 4 of most programs.Reference Thoma, Mohindra and Woods16 With regards to costs, the expense of time-variable training within CBME was likely believed to be important for our nationally funded system. Time-variability may be ideal for the traineeReference Nousiainen, Mironova and Hynes17 but can add cost and uncertainty to the health care system. Such financial outcomes are more system-focused and easier to measure than outcomes that attempt to quantify trainee quality.

2. Trainee focused impact

Trainee-focused clinical outcomes may serve as proxies for better physicians and are typically cited by education scholars as potential benefits of CBMEReference Frank, Snell and Ten18; however, defining and measuring these outcomes will be quite difficult. How can we measure physician quality in EM?Reference Pines, Alfaraj and Batra19 Especially in environments like EM where trainees can so readily access their supervising physicians, how can we tease apart their individual performance?Reference Schumacher, Holmboe, Van Der Vleuten, Busari and Carraccio7,Reference Sebok-Syer, Chahine, Watling, Goldszmidt, Cristancho and Lingard9 Or should we be aiming to find resident-sensitive markers of performance?Reference Schumacher, Holmboe, Van Der Vleuten, Busari and Carraccio7,Reference Sebok-Syer, Chahine, Watling, Goldszmidt, Cristancho and Lingard9,Reference Sebok-Syer, Goldszmidt, Watling, Chahine, Venance and Lingard20 These considerations are important but are beyond the scope of this present project. The quality of physician care is undoubtedly a complex construct that involves numerous competing factors.

3. New methods for evaluation of outcomes

While outcome measurement is important, Gruppen and colleagues warn us not to focus too much on demonstrating that graduates of CBME programs are “better.”Reference Gruppen, Frank and Lockyer2 Instead, we must match the inherent complexity of outcomes with sophisticated study designs, such as collaborative and multicenter studies, focusing on individuals, teams, institutions, and settings. We should also aim to include novel models for program evaluation such as rapid-cycle evaluationReference Hall, Rich and Dagnone21 and realist evaluation (see Appendix 2). Recent evaluation work in EM evaluating early implementation of CBME using rapid evaluation has yielded important lessons about fidelity of implementation, and perhaps even short-term outcomes such as behavior change among stakeholders.Reference Hall, Rich and Dagnone21 Moving forward, these strategies and others will help us tackle the difficult task of high-quality outcome-based evaluation.

Limitations

Our recommendation process has several limitations. Most obviously, the consultatory population that engaged with the initial part of our study (the divergent phase) had a relatively poor response rate, which may relate to the reluctance of trainees and senior leaders to participate in this type of consultation. That said, the dataset that we were able to acquire reached sufficiency for our qualitative analysis and was, therefore, unlikely to have significantly impacted the ultimate outcome of this study. Another limitation is the narrow nature of our study question; we were specifically seeking to derive a list of clinical and educational outcomes relevant to EM training in Canada. For this reason, our results may have limited generalizability to other specialties and jurisdictions.

Final recommendations

In this three-phase study, we developed consensus recommendations for clinical and educational CBME outcomes. We have defined a novel framework to describe outcomes that were stratified by their inherent nature (clinical or educational), the timing of their impact, and their scope of impact (micro, meso, or macro). This framework has allowed us to identify a broad range of outcomes and organize them into a list of 15 educational and 10 clinical themes (ranked by importance). The main strength of our study was the ability to obtain input from all targeted expert groups from across the country and to prioritize these outcomes during the education summit. Our results will help to operationalize CBME program evaluation and determine its impact on our programs and clinical care in EM.

Through our three-phase study design, we have derived a set of general recommendations regarding outcomes and program evaluation of CBME:

1. We should measure educational and clinical outcomes in CBME to ensure that this model of assessment is meeting the needs of our patients.

2. Initial educational outcomes in the early rollout of CBME should include: measuring EPA observations and feedback, determining the amount of simulated assessment used in CBME, and monitoring and measuring trainee wellness and health.

3. Initial clinical outcomes in the early rollout of CBME should include: measuring patient safety and quality care metrics associated with CBME residents and graduates, demonstrating evidence-based practice of CBME residents and graduates, and monitoring efficiency/impact of CBME on hospital flow and function.

4. Specialty-specific micro (patient/training site, learner/training program), meso (institution or region), and (national) macro outcomes will need to be measured by means of robust research methods linking educational and clinical outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

We have created a key listing of educational and clinical outcomes that should be targeted both in the short- and long-term to determine the impact of CBME on the practice of Canadian EM. Clinician Educators and Education Scholars should use the recommendations to inform future program evaluation initiatives of CBME.

Supplemental material

The supplemental material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2019.491.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jeff Perry for his leadership of the academic section of Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians and Dr. Ian Stiell for championing educational scholarship both in his foundational work with the academic section and as the Editor-in-Chief of the Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine.

Competing interests

None.