EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This executive summary will provide a brief overview of consensus statements on sonography in hypotension and cardiac arrest (SHoC) recommended by the International Federation for Emergency Medicine (IFEM) for use in emergency medicine (EM).

Purpose

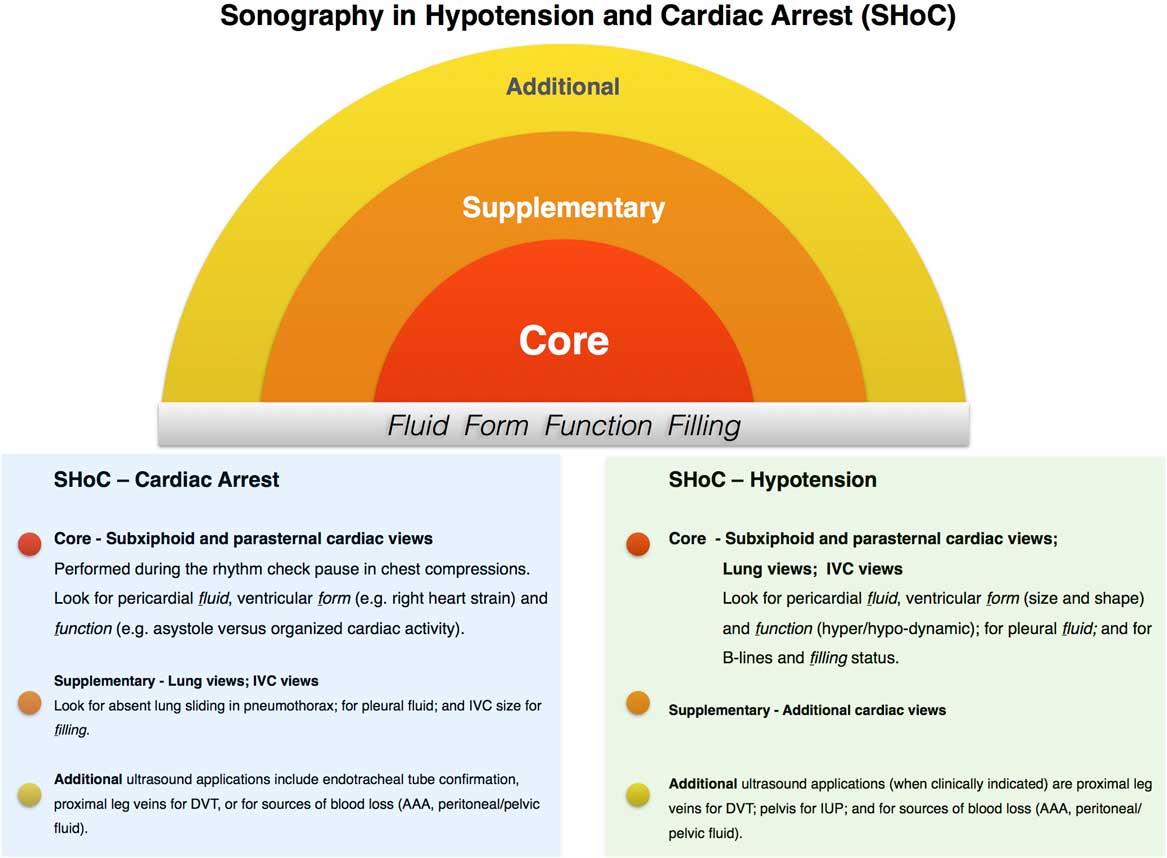

As point of care ultrasound (PoCUS) has become an established tool in the initial management of patients with undifferentiated hypotension and during cardiac arrest, the Ultrasound Special Interest Group (USIG) of IFEM was tasked to provide consensus guidance for use in EM that was designed to be widely implementable internationally, and which was targeted at likely etiologies as well as guiding resuscitation. The protocols were also aimed at minimizing interruption of ongoing resuscitation. A hierarchical model was proposed, to be developed by expert consensus based upon disease incidence, previously published protocols, and the medical literature. A practical checklist was to be developed, along with a standardized approach to the performance of scans based upon a “4 F” approach: fluid, form, function, filling.

Consensus approach

We summarized the recorded incidence of PoCUS findings from two international multicentre prospective studies in addition to a checklist to guide clinicians incorporating PoCUS into the resuscitation of the arrested patient based on the current literature. Rates of abnormal PoCUS findings were presented to an international expert panel, and using this data we obtained the input of a panel of international experts associated with five professional organizations led by IFEM. Using a modified Delphi approach, after three rounds of the survey, agreement was reached on SHoC-hypotension and SHoC-cardiac arrest protocols comprising core, supplementary, and additional views for each situation, emphasising the importance of clinical probability to guide the priority of scanning. Agreement was also reached on the contents of the checklist.

Recommendations

This international consensus, based on prospectively collected disease incidence, describes two Sonography in Hypotension and Cardiac Arrest (SHoC) protocols, comprising of the stepwise clinical-indication based approach of Core, Supplementary, and Additional PoCUS views.

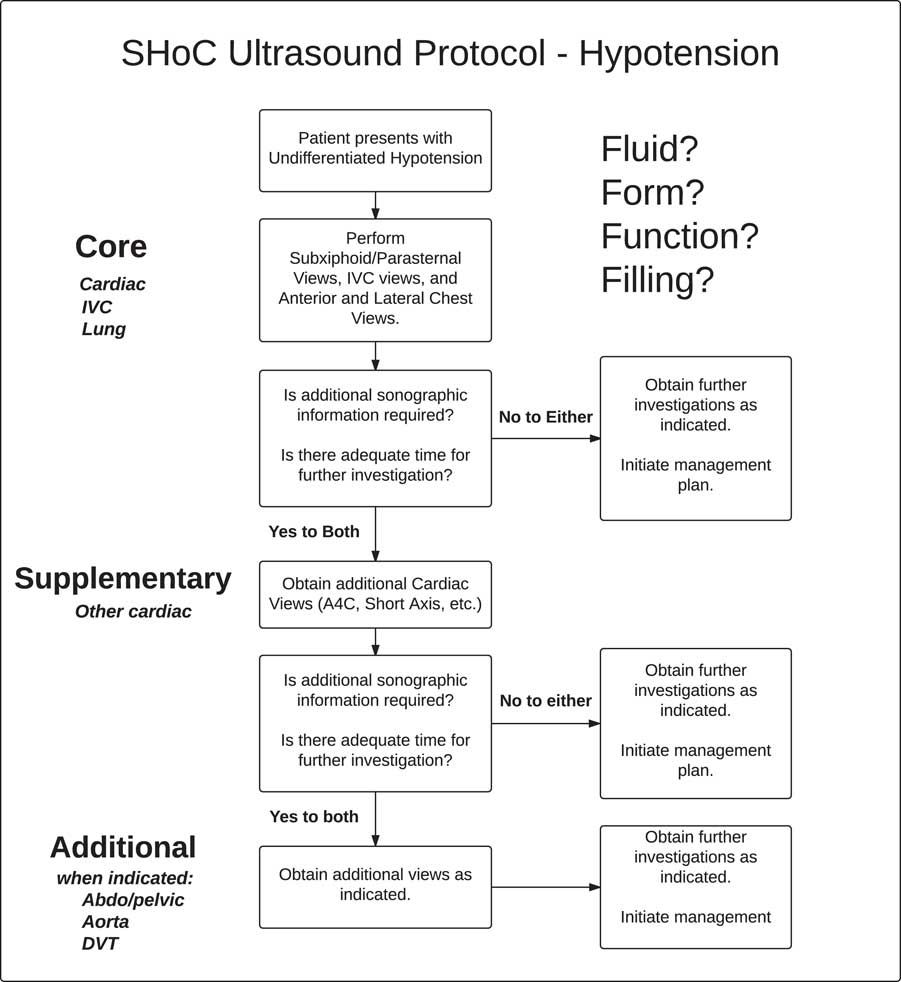

The SHoC-hypotension protocol contains:

Core views focusing on determining the category of shock, whether cardiogenic or non-cardiogenic, and consisting of:

-

1. Basic cardiac views (primarily the sub-xiphoid window, or parasternal long axis window for pericardial fluid, cardiac form and ventricular function);

-

2. Lung views for pleural fluid and B-lines for filling status; and

-

3. Inferior vena cava (IVC) views for filling status.

Supplementary views consisting of other cardiac views; with Additional views performed where clinically indicated (e.g., AAA; pelvic; DVT).

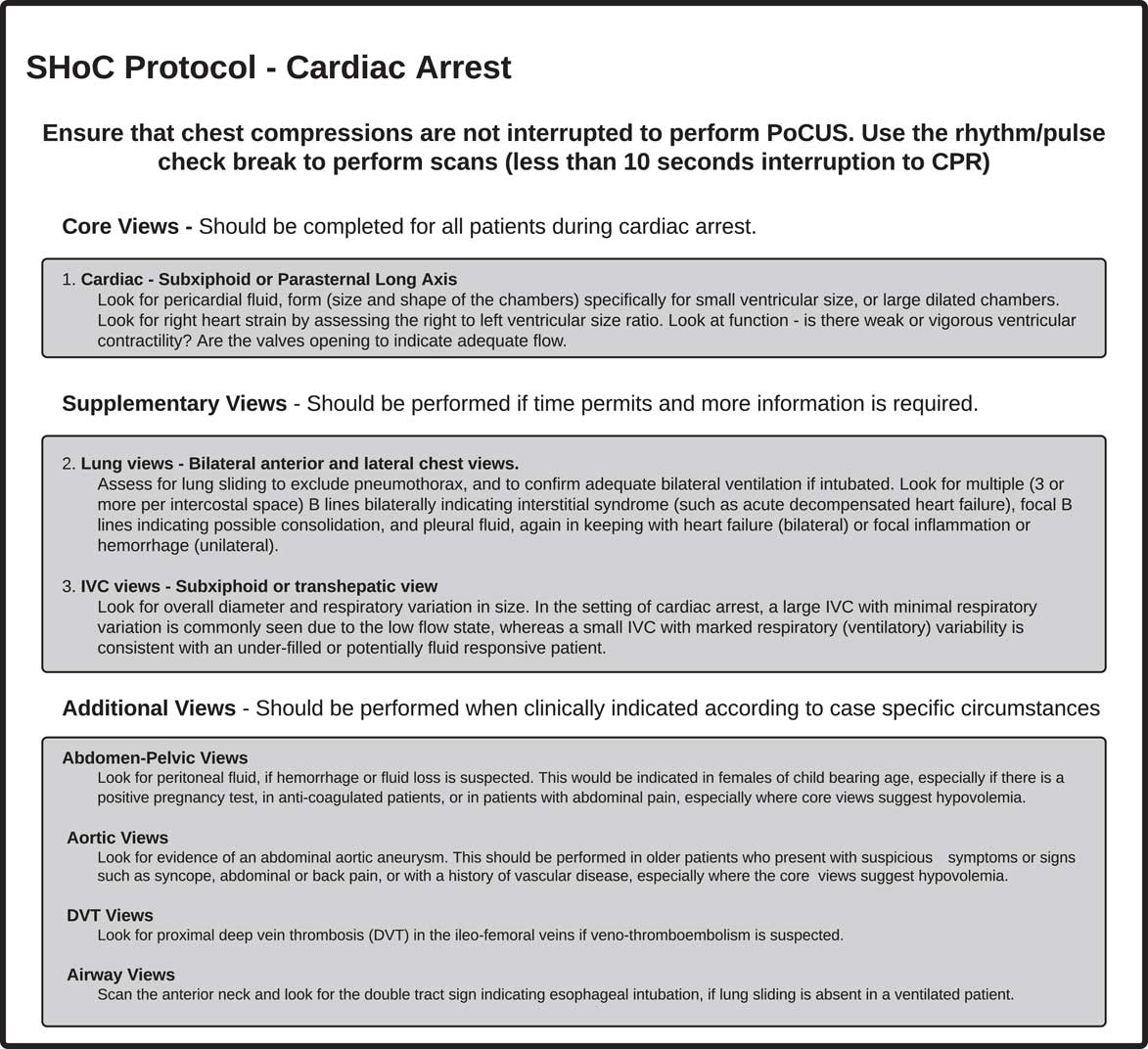

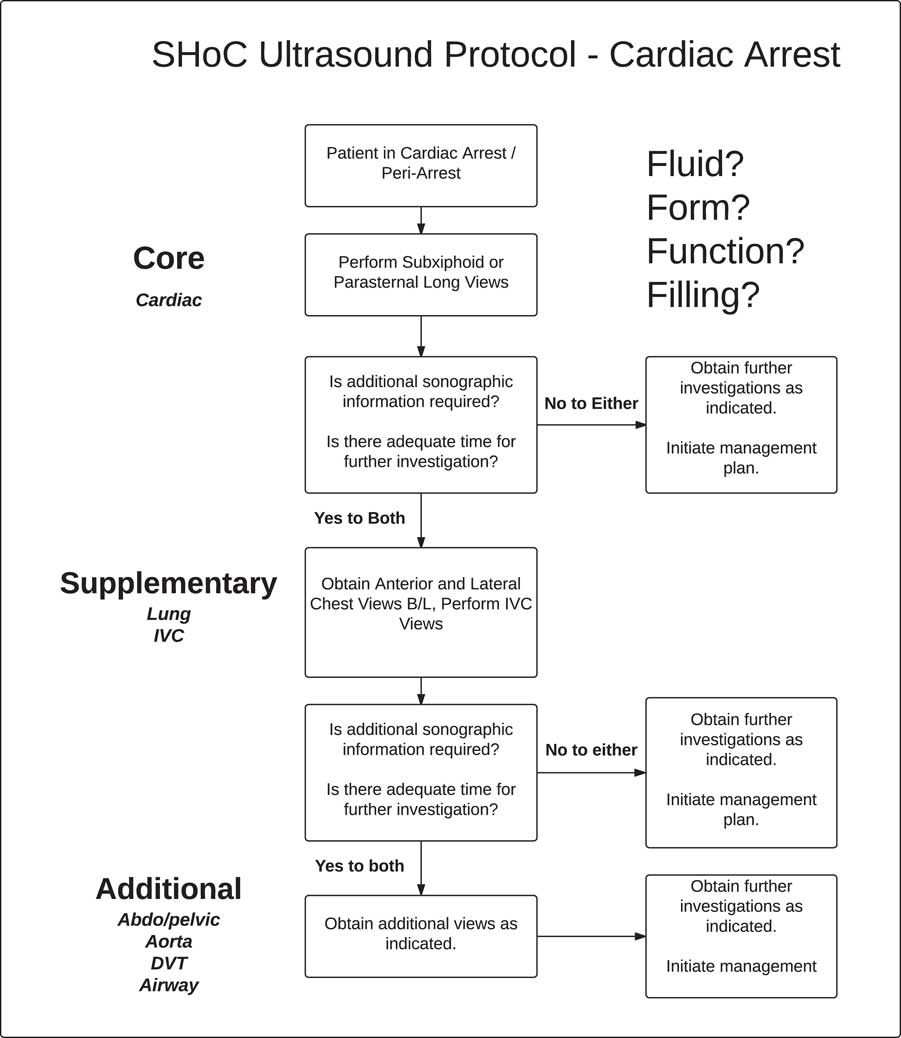

The SHoC-cardiac arrest protocol contains:

Core views, limited to cardiac windows (primarily sub-xiphoid or parasternal long axis) and must be performed during the rhythm check pause in chest compressions, without causing prolonged interruption in chest compressions. These windows should be used to look for pericardial fluid, as well as examining ventricular form (e.g., right heart strain) and function, (e.g., asystole versus organized cardiac activity).

Supplementary views consisting of lung (for sliding or fluid) and IVC views; with Additional views such as confirmation of endotracheal tube placement or exclusion of aortic aneurysm performed when clinically indicated.

An operational checklist for the use of PoCUS during cardiac arrest is provided and includes the following key steps:

-

1. Team briefing

-

2. Preparing the ultrasound machine prior to patient arrival (if time permits)

-

3. Performing the scan during breaks in CPR

-

4. Reviewing the images during CPR

-

5. Clinical decision making and interventions based on PoCUS findings and reassessment

-

6. Completion of scanning

-

7. Post-resuscitation actions

These protocols are focused to direct the clinician to perform views that are clinically indicated, which aims to improve efficiency and reduce the frequency of potentially distracting incidental positive findings that can accompany the current “one size fits all” standard protocols. Figure 1 helps to conceptualize the hierarchical core/supplementary/additional views approach of the SHoC algorithms. This clarifies the essential views for hypotension and cardiac arrest, as well as demonstrating the foundational role that the “4F” approach of fluid, form, function, and filling plays in the SHoC protocol.

Figure 1 Summary “target style” graphic for the combined SHoC protocols.

INTRODUCTION

The use of point of care ultrasound (PoCUS) as an adjunct to the practice of emergency medicine is now well established internationally. Initially, evidence to support the use of PoCUS came from the management of blunt trauma patients.Reference Scalea, Rodriguez and Chiu 1 The scope of practice has expanded as emergency physicians have identified further clinical problems where PoCUS is able to aid diagnosis and guide procedures. Assessment of patients in cardiac arrest and with undifferentiated hypotension are core applications of PoCUS, with various protocols in widespread use in emergency medicine.Reference Perera, Mailhot and Riley 2 , Reference Atkinson, McAuley and Kendall 3 Previously published protocols are based upon a logical approach to identifying the likely etiology and guiding therapy, but these protocols are frequently based solely on expert opinion and not on the actual incidence of disease, and tend to follow a didactic rigid approach.Reference Jones, Tayal and Sullivan 4 - Reference Elmer and Noble 5 Evidence supporting the use of PoCUS in hypotension is limited to diagnostic improvements.Reference Jones, Tayal and Sullivan 4 - Reference Elmer and Noble 5 The International Federation for Emergency Medicine (IFEM) Ultrasound Special Interest Group (USIG) was tasked with development of a consensus approach to the use of PoCUS in patients with hypotension and cardiac arrest, taking into account previously published recommendations as well as the reported incidence of disease seen with PoCUS in these clinical scenarios.Reference Milne, Atkinson and Lewis 6

PoCUS is an invaluable tool that has potential to clarify essential diagnoses and yield findings that alter management plans.Reference Jones, Tayal and Sullivan 4 , Reference Elmer and Noble 5 For undifferentiated hypotension, it enables a clinician to assess the category of shock and the response to initial management.

Previously published algorithms fail to adopt a hierarchical approach to their various components,Reference Scalea, Rodriguez and Chiu 1 - Reference Atkinson, McAuley and Kendall 3 and most recommend that every patient receives every view, every time. The aim of this consensus was to develop an approach that could be adapted to each clinical scenario.

For cardiac arrest patients, although PoCUS is commonly taught and performed, 7 to our knowledge no guidelines have yet addressed practical issues such as operator safety and minimizing delays in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

The objectives of this group were to provide consensus-based approaches incorporating reported disease incidence for the use of sonography in hypotension and cardiac arrest (SHoC). The SHoC protocol is presented along with a consensus developed Checklist for clinicians who wish to safely incorporate PoCUS into the resuscitation of the arrested patient.

METHODOLOGY

The IFEM USIG invited 24 recognized international leaders in PoCUS from emergency medicine and critical care to form an expert panel to develop the SHoC protocol. Baseline disease incidence was derived using the reported interim findings of two multicenter prospective studies that examined ultrasound use in undifferentiated hypotension and in cardiac arrest (see Tables 1 and 2).Reference Milne, Atkinson and Lewis 6 The panel was also provided with a list of recommended PoCUS views in previously published protocols and guidelines (see Table 3). Using a modified Delphi methodology, the expert panel was tasked with integrating the disease incidence, their clinical experience, and their knowledge of the medical literature to evaluate what role each view should play in the proposed SHoC protocol.Reference Okoli and Pawlowski 8 The panel was asked to assign these views to any of four different priorities in the hierarchical approach, and provide a rationale for their decision (see Table 4). The panel was also asked to structure the protocol in a manner that would be efficient to perform, and would be consistent with current standardized methods for teaching critical care PoCUS (see Table 5).

Table 1 International data for incidence of ultrasound findings in undifferentiated hypotensionReference Milne, Atkinson and Lewis 6

AA = abdominal aortic aneurysm; IV = inferior vena cava; L = left ventricular.

Table 2 Local data for incidence of ultrasound findings in cardiac arrestReference Milne, Atkinson and Lewis 6

Table 3 PoCUS views assessed by the expert panel for inclusion in the SHoC protocols:

DVT = deep venous thrombosis; IVC = inferior vena cava; PoCUS = point of care ultrasound; SHoC = sonography in hypotension and cardiac arrest.

Table 4 Hierarchy levels for scans to be included:

Table 5 Teaching structure for key findings

IVC = inferior vena cava; LV = left ventricular; RV = right ventricular.

Reaching consensus

Consensus on the SHoC protocols for hypotension and cardiac arrest was reached after three rounds of the modified Delphi process. Typically, consensus was declared for a given view after that view was assigned to a certain hierarchy with a two-thirds majority at that level or higher (see Appendix 1).

In addition to this process, panel members reviewed, modified, and approved an operator Checklist to guide clinicians incorporating PoCUS into the assessment and resuscitation of the arrested patient developed by the Ultrasound Subcommittee of the Australasian College of Emergency Medicine (ACEM), using the described consensus methods. Current recommendations from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation and its member organisations were provided to the panel.Reference Soar, Nolan and Böttiger 9 , 10

The final SHoC protocol and operator Checklist received panel consensus approval (SHoC-hypotension received 82%, and SHoC-cardiac arrest received 83% approval of panel members). The IFEM Board approved the final recommendations.

RECOMMENDATION

1. SHoC-Hypotension

The expert panel reached consensus and recommends the following SHoC-hypotension protocol.

Core views focus on determining the category of shock, whether cardiogenic or non-cardiogenic, and consist of:

-

1. Basic cardiac views (primarily the subxiphoid window, or parasternal long axis window for pericardial fluid, cardiac form and ventricular function);

-

2. Lung views for pleural fluid and B-lines for filling status; and

-

3. IVC views for filling status.

Supplementary views should be performed if further information is required regarding pericardial fluid or cardiac form or function, and include the additional cardiac views (parasternal short axis and apical views).

In many clinical scenarios determining a source of hypovolemia or cardiovascular strain is essential. To assist with this, Additional views including peritoneal fluid, aorta, pelvic for intrauterine pregnancy (IUP), and proximal leg veins for deep venous thrombosis (DVT) should be performed when indicated. Importantly, although the consensus reached was to include abdomino-pelvic views for peritoneal fluid as an Additional (or optional) view, this should be considered Supplementary (ranked as more important) for women of childbearing age.

2. SHoC-Cardiac Arrest

The expert panel reached consensus and recommends the following SHoC-cardiac arrest protocol. The agreed protocol focuses on the timing of PoCUS as well as specific clinical questions.

Core views are limited to cardiac views and must be performed during the rhythm check pause in chest compressions, without causing prolonged interruption in chest compressions. The preferred view is the subxiphoid window or the parasternal long axis window if necessary. Either view should be used to look for pericardial fluid, as well as examining ventricular form (e.g., right heart strain) and function, (e.g., asystole versus organized cardiac activity).

Supplementary views include lung views (for absent lung sliding in pneumothorax and for pleural fluid), and IVC views for filling.

Additional applications that may assist during cardiac arrest include the use of PoCUS for endotracheal tube confirmation, scanning proximal leg veins for DVT, or looking for sources of blood loss (AAA, peritoneal or pelvic fluid).

These consensus protocols do not specify how findings should direct clinical management. They instead represent a consensus on the prioritization of scanning for these critically ill patients, based on the likelihood of detection of underlying pathology, and the perceived impact on patient management.

DISCUSSION

PoCUS is an essential tool for the evaluation of many patients in the ED. A “one size fits all” investigation is rarely appropriate for any critically ill ED patient, yet this is how many of the current PoCUS protocols approach patients with undifferentiated hypotension (all patients get all included views, all the time) or cardiac arrest. Examples of commonly recommended, yet rarely positive views are those for peritoneal fluid and for aortic aneurysm. It is likely that, as these views were commonly taught as core emergency ultrasound scans, they have been included in hypotension protocols as a result of familiarity. Our expert panel reached the consensus that, although obtaining peritoneal views to assess for peritoneal fluid or views for AAA are essential in certain patient categories, the diagnostic yield is low and rarely helpful as a first-line scan. The SHoC protocols’ hierarchical approaches, based on the pre-test probability of disease, are advantageous over current “one size fits all” standards.

In the SHoC-hypotension protocol, all patients first receive a basic cardiac view, such as the subxiphoid or parasternal long axis window to look for pericardial fluid, the form, or size and shape of the cardiac chambers, and the function of the ventricles; next, lung views for evidence of pneumothorax, multiple bilateral B-lines indicating potential pulmonary edema, or pleural effusions consistent with congestive heart failure; and then and an IVC view looking for respiratory variation in size. Together these views should help determine whether the hypotensive patient is likely to be fluid responsive or not; a key initial factor in resuscitation. These views will also exclude clinically obscure pathology such as cardiac tamponade. In patients for whom a diagnosis is not immediately clear and for whom definitive management would not be delayed, supplementary cardiac views, such as the parasternal short and apical windows, should also be obtained. Additional views are only recommended when clinically indicated to exclude specific suspected pathology.

In the SHoC-cardiac arrest protocol, the focus is to obtain a global view of the heart during the hiatus in chest compressions for a brief rhythm check. The core sub-xiphoid view, or back-up parasternal long axis view, will enable detection of pericardial fluid, as well as a focused assessment for cardiac form and function. The detection of potentially reversible causes of cardiac arrest is essential during the early phases of the management of patients with non-shockable rhythms. Detection of a massively enlarged right ventricle may indicate an underlying pulmonary embolism, whereas vigorous ventricular contractility may indicate a hypovolemic state. Supplementary views include lung and IVC views. These views will be achievable during established resuscitation or in the peri-arrest or post-resuscitation phase. Bilateral lung sliding confirms adequate ventilation and excludes tension pneumothorax. Multiple B-lines or bilateral pleural effusions may point to congestive heart failure. A small collapsing IVC may confirm a hypovolemic state. A large dilated IVC is a common finding during cardiac arrest. Again, additional views are only recommended when clinically indicated, and must not interrupt ongoing chest compressions, but may assist with procedures such as confirmation of tracheal intubation. The checklist (provided in Appendix 2) may be used with the SHoC-cardiac arrest protocol to guide practitioners in the practical details related to the performance of PoCUS when resuscitating a patient in cardiac arrest.

We believe that a hierarchical approach, based upon established incidence of disease or the estimated likelihood of disease is consistent with the fact that PoCUS should be used as a diagnostic tool, instead of a screening tool. When a scan is performed to assess for an unexpected etiology (a screening scan), a positive finding is more likely to be incidental and may distract from the underlying diagnosis. If the same scan is performed for an expected etiology (a diagnostic scan), a positive finding is far more likely to be pertinent to the accurate diagnosis. The SHoC protocol is the first PoCUS approach with an international consensus that is focused on diagnostic and resuscitative purposes. These recommendations are derived from expert consensus in an effort to standardize the approach to PoCUS in critically ill patients. Research needs to be performed to validate this approach, and to show it improves patient outcomes over existing resuscitation protocols. The recommended protocols are depicted in Figures 2-5 and in Appendices 1 and 2.

Figure 2 Included views in the SHoC-hypotension protocol.

Figure 3 SHoC-hypotension protocol summary.

Figure 4 Included views in SHoC-cardiac arrest protocol.

Figure 5 SHoC-cardiac arrest protocol summary.

CONCLUSION

We present an international consensus for the use of sonography in hypotension and cardiac arrest (SHoC) based on prospectively collected disease incidence. The proposed SHoC protocols for hypotension and cardiac arrest, and the cardiac arrest checklist, are stepwise clinical-indication based approaches, incorporating Core, Supplementary, and Additional PoCUS views.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the following individuals for their time and expertise as members of the expert panel and advisory committees: Paul Atkinson, Justin Bowra, David Lewis, Rip Gangahar, Mike Lambert, Bob Jarman, Vickie Noble, Hein Lamprecht, Tim Harris, Melanie Stander, Christofer Muhr, Jim Connolly, Romolo Gaspari, Ross Kessler, Chris Raio, Paul Sierzenski, Beatrice Hoffmann, Chau Pham, Michael Woo, Paul Olszynski, Ryan Henneberry, Oron Frenkel, Jordan Chenkin, Greg Hall, Louise Rang, Maxime Valois, Chuck Wurster, Mark Tutschka, Rob Arntfield, Jason Fischer, Mark Tessaro, J. Scott Bomann, Adrian Goudie, Gaby Blecher, Andrée Salter, Michael Rose, Adam Bystrzycki, Shailesh Dass, Owen Doran, Ruth Large, Hugo Poncia, Alistair Murray, Jan Sadewasser, Raoul Breitkreutz, Larry Melniker, Rip Gangahar, Toh Hong Chuen, Arif Alper Cevik, Ang Shiang-Hu, Raoul Breitkreutz, Hong Chuen Toh, Arif Alper Cevik, Ang Shiang Hu, and Larry Melniker.

We also wish to thank Ms. Carol Reardon, Dr. Terry Mulligan and Dr. Jim Ducharme of IFEM for their advice on the manuscript.

APPENDIX 2. ULTRASOUND IN CARDIAC ARREST: CHECKLIST

Preamble

This is a checklist to guide practitioners in the performance of point of care ultrasound (PoCUS) when resuscitating a patient in cardiac arrest. It has been developed by the Ultrasound Subcommittee of the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine (ACEM) and the Ultrasound Curriculum Working Group of the International Federation for Emergency Medicine (IFEM). It incorporates recommendations from International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) member organisations and the international consensus process on PoCUS in shock and cardiac arrest led by IFEM.

Checklist

Please note that the checklist only applies to patients in cardiac arrest and also that the Advanced (Cardiac) Life Support (ALS/ACLS) algorithm takes priority at all times. Please also see the Notes section for a detailed explanation of the checklist.

-

1. Team briefing

-

a. Is it likely that PoCUS will alter the outcome of this case?

-

▪ Yes: team leader assigns a team member to perform PoCUS

-

▪ No: continue standard ALS/ACLS

-

b. Safety briefing

-

c. Which side of patient to set up ultrasound machine?

-

d. Scanning team member is to scan and save images during rhythm checks

-

2. Prepare the machine prior to patient arrival (if time permits)

-

a. Patient details: choose “temporary ID”

-

b. Probe: sector ideal, curved acceptable

-

c. Preset: cardiac ideal, abdominal or “FAST” acceptable

-

d. Initial window (core cardiac): sub-xiphoid ideal, parasternal long-axis acceptable

-

e. Depth (and focus if available) set to 25 cm for adult subcostal, far gain turned up

-

f. Save video clips or cine-loops rather than still images

-

g. Position probe during CPR if possible, to set up your view before break in CPR

-

3. Perform the scan during breaks in CPR

-

a. Core views (cardiac): fluid, form, function

-

b. Consider Supplementary views: lungs, inferior vena cava (IVC)

-

c. Consider Additional views as clinically indicated

-

4. Review the images during CPR

-

5. Clinical decisions and interventions based on PoCUS findings and then reassess.

-

6. Cease scanning when team leader decides that PoCUS is non-contributory or no longer required.

-

7. Post-resuscitation

-

a. Amend patient details on the US machine, then save exam

-

b. Documentation in clinical record

-

c. Clean up and debrief

Notes

Team briefing. This can occur prior to ALS/ACLS or at any stage during ALS/ACLS. Although PoCUS may improve outcomes in patients with reversible causes for cardiac arrest (CA), not all clinicians are trained in focused cardiac US and not all cases of CA require PoCUS (e.g., shockable rhythm with return of spontaneous circulation). Safety briefing is crucial: the team member performing the scan will have their hands and the transducer in contact with the patient while the defibrillator is “live”.

Preparing the machine. Ideally this step should have been considered and planned in advance, with the ideal pre-set / cine-loop length, / retrospective loop function programmed by the local ED team. Choose “temporary ID” or enter patient details after resuscitation is completed. Choice of probe / transducer is up to the individual. Sector probe is ideal in adults, curvilinear probe is acceptable, and linear probe (ideally using trapezoid/“virtual convex” setting) is ideal for infants. If focal zone is available on the machine, set this at 20-25 cm. It is preferable to save video clips/cine-loops rather than still images. When preparing to scan, test whether the machine is saving prospective or retrospective loops by pressing the “save” button. Also consider whether you can find and can review saved loops with the team leader.

Performing the scan and reviewing images. Timing is crucial. Obtain and record images during breaks in CPR, but review images during CPR. Show the loops to the team leader, and try not to distract the rest of the team.

Core views (cardiac):

-

▪ Fluid in pericardial space suggests pericardial tamponade in the appropriate clinical context. Other signs are generally sought e.g., right ventricular (RV) diastolic collapse, but details are beyond the scope of this document.

-

▪ Form: a small left ventricle (LV) suggests hypovolemia. A grossly dilated LV suggests chronic cardiac failure. If the RV diameter is greater than that of the LV, this suggests right heart strain (e.g., pulmonary embolus [PE]).

-

▪ Function: although absence of organised LV activity suggests a poor outcome, it has not been shown to be 100% predictive of futility.Reference Gaspari, Weekes and Adhikari 11

Supplementary views (lung, IVC). These should be sought only if time permits and additional information required.

-

▪ Lungs: if clinical suspicion of tension pneumothorax (TPTX) or endotracheal tube (ETT) misplacement scan the anterior surface of each hemithorax; consider additional lung views if clinical suspicion of other pathology. Note that in both TPTX and unventilated lung, lung sliding is absent on US. Differentiating requires a combination of clinical assessment (e.g., how far down is ETT? Is there any reason for PTX in this patient? Is the patient difficult to ventilate?) and US features (presence of lung pulse or any comets, B-lines will rule out PTX on that side). It is not recommended to seek the ”lung point” sign as this only present in smaller PTX and will be absent in both unventilated lung and TPTX. If there is still doubt, either or both finger thoracostomy or ETT withdrawal may be considered at the discretion of the team leader.

-

▪ Inferior vena cava (IVC): a large IVC with minimal respiratory variation is usual in cardiac arrest whereas a small IVC with marked respiratory (ventilatory) variability suggests fluid-responsive patient.

Additional views. These should be performed when clinically indicated according to the specific circumstances of the case.

-

▪ Intraperitoneal fluid (e.g., clinical suspicion of ruptured ectopic pregnancy)

-

▪ Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) may be an incidental finding in the arrested patient. Once again, clinical context is paramount.

-

▪ Proximal deep venous thrombosis (DVT) (if suspicion of PE and inconclusive cardiac views)