No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 25 March 2010

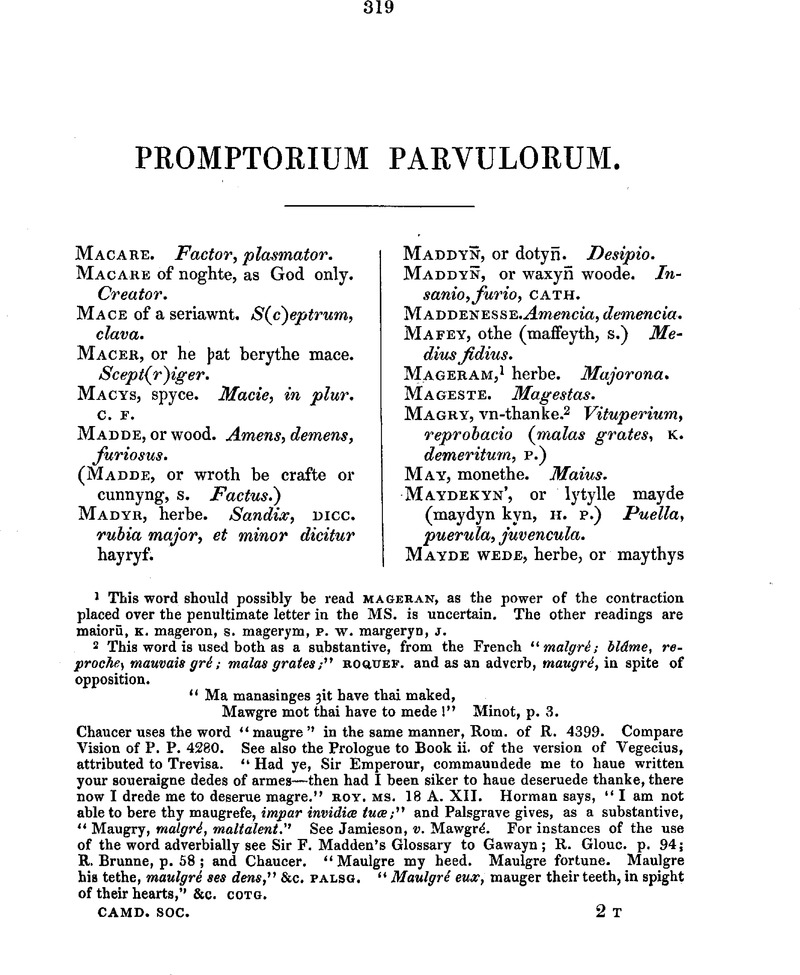

page 319 note 1 This word should possibly be read Mageran, as the power of the contraction placed over the penultimate letter in the MS. is uncertain. The other readings are maiorū, K. mageron, S. magerym, P. W. margeryn, J.

page 319 note 2 This word is used both as a substantive, from the French “malgré; blâme, reproche, mauvais gré; malas grates;” Roquef. and as an adverb, maugré, in spite of opposition.

“Ma manasinges ”it have thai maked,

Mawgre mot thai have to mede !” Minot, p. 3.

Chaucer uses the word “maugre” in the same manner, Rom. of R. 4399. Compare Vision of P. P. 4280. See also the Prologue to Book ii. of the version of Vegecius, attributed to Trevisa. “Had ye, Sir Emperour, commaundede me to haue written your soueraigne dedes of armes—then had I been siker to haue deseruede thanke, there now I drede me to deserue magre.” Roy. ms. 18 A. XII. Horman says, “I am not able to bere thy maugrefe, impar invidiæ tuæ;” and Palsgrave gives, as a substantive, “Maugry, malgré, maltalent.” See Jamieson, v. Mawgré. For instances of the use of the word adverbially see Sir F. Madden's Glossary to Gawayn; R. Glouc. p. 94; R. Brunne, p. 58; and Chaucer. “Maulgre my heed. Maulgre fortune. Maulgre his tethe, maulgré ses dens,” &c. Palsg. “Maulgré eux, mauger their teeth, in spight of their hearts,” &c. Cotg.

page 320 note 1 See Maythys. Anthemis cotula, Linn. Ang.-Sax. ma“eðe, chamæmelum.

page 320 note 2 The old writers occasionally use the term maiden in reference to either sex. In the Vision of P. P. 5525, Wit, discoursing of ill-assorted matrimony, commends alliances between “maidenes and maydenes.” In the Liber Festivalis it is said that St. Luke “went to our Lady, and she taught him the gospell that he wrothe, and for he was a clene mayden, our Ladi cherished him the more.” Ed. Rouen, 1491, f. cliij. “Mayde of the mankind, puceau. Maide of the woman kynde, pucelle.” Palsg.

page 320 note 3 “To mayne, mutulare. Maynde, mutulatus. A maynynge, mutulacio.” Cath. ang. “I mayne, or I mayne one, I take the vse of one of his lymmes from hym, I'affolle, and Ie mehaigne, but mehaigner is Normante.” Palsg. The participle “mayned” occurs in the Golden Legend, f. 121, b. Compare mahennare, mahemiare, Duc.; and the old French mehenier, mehaingner.

page 320 note 4 The second word is here contracted in the MS. and should possibly be read memprisyd. By a writ of main-prize the sheriff is commanded to take sureties for the appearance of a prisoner, called mainperners, or mainprisours, and to set him at large. This is done either when bail has been refused, or when the cause of commitment is not properly bailable. Of the distinction between manucapere and balliare, see further in Spelman.

page 320 note 5 This plant is thus mentioned by G. de Bibelesworth; Arund. MS. 220, f. 301.

“Si vous trouet en toun verger

Amerokes (maþen) e gletoner (and cloten,)

Les aracez de vn besagu (twybel.)”

In the Vocabulary of names of plants, Sloane MS. 5, is given “Amarusca calida, Gall, ameroche, Ang. maithe;” in another list, Sloane MS. 56, “cheleye, i. mathe.” The camomile is still known by the appellation Mayweed; Anthemis cotula, Linn. Gerarde describes the “May weed, wild cammomill, stinking mathes, or mauthen,” Cotula fætida, and observes that the red kind grows in the west parts of England amongst the corn, as Mayweed does elsewhere, and is called “red maythes, our London women do call it Rose-a-rubie.” Ang.-Sax. ma“eðe, ma“ða, chamæmelum.

page 321 note 1 Maak in the Craven Dialect still means a maggot. Dan. mak, madike, vermis.

page 321 note 2 “Collega, a make, or a yomanne.” Med. In the edition of the Ortus in Mr. Wilbraham's library collega is rendered “a make, or a felowe.” This term, as used by Chaucer and other writers, has the signification of a mate, or fellow, a spouse, either husband or wife. It is said of the turtle dove in the Golden Legend, “When she hath lost her make, she wyll neuer haue other make.” See Jamieson. A.-S. maca, consors.

page 321 note 3 The substantive a-cethe has occurred previously, p. 5, where the word has been printed A-cethen, a contraction appearing in the Harl. MS. over the final Ē. which, however, is probably erroneous. The word is thus used in the earlier Wicliffite version: “Now than ryse, and go forth, and spekynge do aseethe to thi seruauntis;” in the later, “make satisfaccioun (satisfac servis tuis,” Vulg.) ii. Kings, xix. 7. In the later version it occurs in i. Kings, iii. 14: “Therfore y swore to the hows of Heli that the wickidnes of hys hows shal not be doon a-seeth before with slayn sacrifices and giftis;” in the earlier, “schal not be clensid (expietur,” Vulg.) See also Mark xv. 15. “Asethe, satisfaccio. To make asethe, salisfacere.” Cath. ang. “Satisfactio, (sic) to make a-sethe.” Ortus. Chaucer, in the Rom. of Rose, 5600, rendered “assez—asseth;” and in the passage previously cited from the Vis. of P. P. the line is printed by Mr. Wright, “if it suffise noght for assetz,” where he explains the word as synonymous with the common law term, assets. Compare Fulfyllyn, or make a-cethe in thynge þat wantythe; p. 182.

page 321 note 4 Some doubt may here arise as to the power of the contractions in the MS. cōuenaunt, or cōnaunt. Compare Breke cōuenant, p. 50, and see the note on cūnawnte, p. 108.

page 322 note 1 The adjective Make has occurred already, and the reading of the King's Coll. MS. gives easy, as synonymous therewith. Jamieson cites Douglas, who uses the word in the sense of evenly, or equally. Compare Ang.-Sax. macalic, opportunus; Belg. maklyk, easy. Sir Thomas Brown gives matchly as a Norfolk word; it is likewise given by Forby, and signifies exactly alike, fitting nicely; the modern pronunciation being, as stated by the latter, mackly. Ang.-Sax. maka, par.

page 323 note 1 This term denotes most commonly the disease in the legs of horses, as causing them mal andare, to go ill, according to Skinner's observation. Malandria, however, in medieval Latin, as in French, malandrie, denoted generally an ulcer, a disease difficult of cure, as leprosy. See Ducange. “Malandrie, sickenesse, malandre. Malandre, malandre, serot.” Palsg. In a veterinary treatise, Julius, D. Viii. f. 114, the following remedy is given “for the Malaundres. Tac parroures of chese, and tac hony, and tempre hem to-gedre, and ley hit on þe sore as hot as þou may.”

page 323 note 2 “A male, mantica, involucrum.” Cath. ang. “Male, or wallet to putte geare or stuffe in, malle.” Palsg. Horman says, “Undo my male, or boudget (bulga, hippopera, bulgula.)” The horse by which it was carried was termed a somer, or sompter horse, sommier. See Somer hors, hereafter. In Norfolk the cushion to carry luggage upon, behind a servant attending his master on a journey, is still called a malepillion.

page 323 note 3 “Fornaculum, Fornacale, instrumentum ad opus fornacis, a malkyne, or a malott.” Med. ms. cant. “A malyne (sic), tersorium.” Cath. ang. “Malkyn for an ouyn, frovgon.” Palsg. Holliband renders “Waudrée, the clout wherewith they clense, or sweepe the ouen, called a maukin. Escouillon, an ouen sweeper, a daflin.” “A malkin, vide Scoven (sic). A Scovel or maulken, ligaculum, scopula. Penicillum, a bull's tail, a wisp, a shoo-clout, a mawkin, or drag to sweep an oven.” Gouldm. This term is still used in Somersetshire. It would appear from the Medulla that this word was also used as an opprobrious appellation: “Gallinacius, i. homo debilis, a malkyn, and a capoun.” Forby gives maukin, as signifying either a dirty wench, or a scarecrow of shreds and patches.

page 323 note 4 Compare Bowde, malte-worme; p. 46, and Budde, flye; p. 54. In the Eastern counties weevils that breed in malt are termed bowds, according to Ray, Forby and Moore; the word is repeatedly used by Tusser. R. Holme says that “the Wievell eateth and devoureth corn in the garners: they are of some people called bowds.” Acad. of Arm. B. ii. p. 467. The appellation is applied to other coleopterous insects. Gower compares the envious to the “sharnbudes kynde,” which, flying in the hot sun of May, has no liking for fair flowers, but loves to alight on the filth of any beast, wherein alone is its delight. “Crabro, guedam musca, a gnat, or a sharnebode. Scarabeus, a sharne budde.” Med. R. Holme mentions the “Blatta, or shorn bud, or painted beetle.” Ang.-Sax. scearn, stercus. In Arund. MS. 42, f. 64, an insect is described which devours the young shoots of trees. “Bruk is a maner of flye, short and brodissh, and in a sad husc, blak hed, in shap mykel toward a golde bowde, and mykhede of twyis and þryis atte moste of a gold bowde, a chouere, oþer vulgal can y non þerfore.” The name gold bowde probably denotes a species of Chrysomela, Linn.

page 324 note 1 “Germinatus, commyn as malte.” Ortus. Harrison, in his Description of England, speaking of the making of malt, says that the grain is steeped, and the water drained from it; it is then laid on the floor in a heap, “untill it be readie to shoote at the root end, which maltsters call commyng. When it beginneth therefore to shoot in this maner, they saie it is come, and then forthwith they spread it abroad, first thicke, and afterward thinner and thinner vpon the said floore (as it commeth), and there it lieth by the space of one and twentie dayes at the least.” B. ii. c. 6. Holinsh. i. 169. R. Holme, among terms used by malt-makers, says that “the comeing of barley, or malt, is the spritting of it, as if it cast out a root.” Acad. of Arm. B. iii. p. 105. The little sprouts and roots of malted barley, when dry, and separated by the screen, are still called in Norfolk malt-cumbs, according to Forby. Bp. Kennett gives “Malt comes, or malt comings, the little beards or shoots, when malt begins to run, or come; Yorkshire.” Lansd. MS. 1033. See Craven Glossary and Jamieson. Compare Isl. keima, Germ. keimen, germinare.

page 324 note 2 The strange and superstitious notions that obtained in olden times regarding the mandrake, its virtues, and the precautions requisite in removing it from the soil, are recorded by numerous writers. In an Anglo-Saxon Herbal of the Xth cent. Vitell. C. iii. f. 53, vº, a representation will be found of the plant, at the side of which appears the dog, whose services were used in dragging it up. The account there given of the herb has been printed by Mr. Thorpe in his Analecta. Alex. Neccham, who died 1227, mentions it as if it had been commonly cultivated in gardens, which should be decked, as he observes in his treatise de naturis rerum, “rosis et liliis, solsequiis, molis et mandragoris.” Roy. MS. 12 G. XI. f. 77. The author, however, of the treatise on the qualities of herbs, written early in XVth cent., who appears to have cultivated in his herber at Stepney many botanical rarities, speaks of the “mandrage” as a plant that he had seen once only. He admits that as to any sexual distinction in the roots, “kynde neuere “af to erbe þe forme and þe kynde of man: some takyn seere rootys, and keruyn swuche formys, as we han leryd of vpelonders;” Arund. MS. 42, f. 31, vº. The curious relation that he gives of his detection of an aged man, who kept in a strong chest a mandrake root, which brought him daily “a fayre peny,” is a remarkable illustration of the credulity of the age. See further on this subject Roy. MS. 18 A. VI. f. 83, vº; Trevisa's version of Barthol. de Propr. B. xvij. c. 104; Bulleine's Bulwarke of Defence, p. 41; Browne's Vulgar Errors, and Philip's Flora Historica, i. 324. Singular representations of the “mandragolo” and “mandragola” executed by an Italian designer in the earlier part of the XVIth cent., are preserved in the Add. MS. 5281, f. 125 and 129, vº. The dog drags up the monstrous root by a chain attached to its ancles, whilst his master stops his ears, to escape the maddening effects of the mandrake's screams.

page 325 note 1 This word seems to be derived from mancus, or the old French manche, mutilated, deprived of the use of a hand, or a limb. The participle “mankit,” maimed, occurs in Golagros and Gawane, 1013. See also the passages cited by Jamieson. Compare Teut. mancken, Belg. minken, mutilare.

page 325 note 2 The manuale occurs among the service books which, at the synod of Exeter, in 1287, it was ordained that every parish should provide; Wilk. Cone. ii. 139. The Constitutions of Abp. Winchelsey, in 1305, comprise a similar requisition. Lyndwood defines it as containing “omnia quæ—spectant ad sacramentorum et sacramentalium ministrationem.” It comprises also the various forms of benediction; and in the printed editions of the Manuale ad usum Sarum are added the curious instructions for the seclusion of lepers. “Manuels” are included amongst the books which, by the Stat. 3 and 4 Edw. VI. were “cleerelie and utterlie abolished, and forbidden for euer to be used or kept in this realme.”

page 325 note 3 Mappel seems to be a diminutive of the old French mappe, a clout to wipe anything withal.

page 325 note 4 “A marche, marchia, maritima.” Cath. ang. “Marches bytwene two landes, frontiéres.” Palsg. The frontiers of a country were termed in medieval Latin marchia, in French, marches; and in Britain the terms “marches of Wales—the Northern marches,” were still in use at no very remote period. Ang.-Sax. mearce, fines. See Kilian and Wachter. The verb to march, to border upon, is used by Gower; Sir John Maundevile also describes one course for the pilgrim to the Holy Land “thorghe Almanye, and thorghe the kyngdom of Hungarye, that marchethe to the lond of Polayne (quod conterminum est.)” See Voiage, pp. 8, 50.

page 326 note 1 It has been affirmed that the Mara was reverenced as a deity by the Northern tribes; in Britain it appears only to have been regarded as a supernatural being, the visits of which were to be averted by physical charms, such as the hag-stone, called in the North the mare-stane. Of the popular belief respecting the Ephialtes see the curious passages printed by Mr. Wright in the Introduction to the Trial of Alice Kyteler; and Keysler, Ant. Sept. p. 497. Chaucer gives in the Miller's Tale, v. 3481, a singular night spell, to preserve the house from the approach of spirits, and “the nightes mare.” “Night mare, goublin.” Palsg. It was termed in French godemare, according to Cotgrave. Ang.-Sax. mara, incubus.

page 326 note 2 “A margaryte stone, margarita.” Cath. ang. “Margery perle, nacle.” Palsg. In Trevisa's version of Higden's Polych. B. i. c. 41, amongst the productions of Britain, are mentioned “muscles, that haue within hem margery perles of alle maner of colour and hewe, of rody, and reed purpure, and of blewe, and specially and moost of white.” Chaucer speaks of the precious “margarite perle,” formed in a blue muscle shell on the sea coast of “the More Britaine;” Test, of Love, B. iii. In Arund. MS. 42, f. 12, vº, allusion is made to the supposed cause of the formation of “margery perle—produced in muscle, or cokle, from dew of heaven.” In the Wicliffite version pearls are called “margaritis,” Matt. vii. 6; xiii. 46. Horman observes that “margaritis be called pearles, of a mountayne in the see of Ynde, called Permula, where is plentye of them.”

page 326 note 3 This term is synonymous with that used by Chaucer in reference to the Miller of Trumpington, described as being proud as a peacock, and whom none dared to touch or aggrieve; “He was a market-beter at the full.” Reve's T. 3934. The old Glossarist explained this as denoting one who made quarrels at the market, but it seems rather to imply one who swaggers about, and elbows his way through the crowd. “A merket beter, circumforanus.” Cath. ang. “Circumforanus, a goere aboute þe market.” Med. “Batre les rues, to revell, jet, or swagger up and down the streets a nights. Bateur de pavez, an idle, or continuall walk-street; a jetter abroad in the streets,” rendered also under the word Pavé “a pavement beater, a rakehell,” &'c. Cotg.

page 327 note 1 To marl is retained as a sea term, signifying, according to Ash, to fasten the sails with writhes of untwisted hemp dipped in pitch, and called marlines. Compare Dutch, marrelen, to intangle one in another; Dan. merling, pack-thread.

page 327 note 2 The martyrologium was, in the earlier times, the register of names of saints and martyrs, which served to bring each successively to the memory of the faithful, on the anniversary of his Passion. At a later period the term denoted, in monastic establishments especially, the register more properly called necrologium, or obituary, wherein were inscribed the obits and benefactions of those who had been received into the fraternity of the congregation, and whose names were thus in due course brought to mind, being recited day by day in the chapter, and suitable prayers said. The martyrology was termed also liber vitæ, and the memorial inscribed annotatio Regulæ, because it was generally annexed to the Rule, and connected therewith was the obituary, wherein the deaths of abbots, priors, and members of the congregation in general, were recorded. The martyrologium occurs next to the regula canonicorum, among the gifts of Bp. Leofric to Exeter, in 1050. The nature of the entries made may be seen by Leland's “thingges excerptid out of the martyrologe booke at Saresbyri,” and at Hereford. Itin. iii. f. 64; viii. f. 79. A remarkable specimen of such a register is supplied by the Liber Vitæ of Durham, commencing from Xth century; Cott. ms. dom. a. vii. See Kennett's Glossary to Par. Ant. In the version of Vegecius attributed to Trevisa, Roy. MS. 18 A. XII. it is said that the Roman legions, “with her chosen horsemen i-rolled in the constables martiloge (matriculæ), were euer-more myghty i-nowe to kepe her wardes,” without auxiliaries. B. ii. c. 2. It is here put for the muster-roll, termed album, or pittacium.

page 327 note 3 The martinet or martlet is the Hirundo urbica, Linn. and both appellations appear to have been taken from the French. Skinner considers it to be a diminutive of the proper name, comparing the usage of calling a parrot or a starling Richard, or a ram Robert, and rejects as fanciful the conjecture of Minsheu that the name martinet was given in allusion to its arrival at the end of March, and migration before St. Martin's day. “Martynet, a byrde, martinet.” Palsg.

page 327 note 4 The term marrow is used in this sense by Tusser, but appears to be no longer known in East Anglia. It is retained in the Northern, Shropshire, and Exmoor dialects; see the quotations given in the Craven Glossary, and Jamieson. It occurs in the Townl. Myst. p. 110. “A marrow, or fellow, socius.” Gouldm. Minsheu would derive it from the Hebrew.

page 328 note 1 This term evidently implies the implement used for mashing or mixing the malt, to which, from resemblance in form, the name rudder is also given. In Withal's little Dictionary, enlarged by W. Clerk, among the instruments of the Brew-house, is given “a rudder, or instrument to stir the meash-fatte with, motaculum.”

page 328 note 2 “A maser, cantarus, murra, murreus: hec murpis arbor est.” Cath. ang. “Masar of woode, masière, hanap.” Palsg. There can be little doubt that the maser, the favourite drinking vessel used by every class of society in former times, was called murrus, from a supposed resemblance to the famed Myrrhene vases of antiquity. The maser was, however, formed of wood, especially the knotty-grained maple, and esteemed in proportion to the quality of the veined and mottled material, but especially the value of the bands and rings of precious metals, enamelled, chased, or graven, with which the wood was mounted. In Latin this kind of vessel was called mazerinus, maderinus, madelinus, masdrinum, &c. in French madre, maselin, or mazerin; and it seems probable that the name mether, applied to the ancient cups of wood preserved in Ireland, may be of cognate derivation. Amongst innumerable instances where mention occurs of the cyphus murreus, or maser, in wills and other documents, may be cited the Inventories taken at St. Paul's, 1295, printed by Dugdale, and at Canterbury, 1328, given by Dart from Cott. MS. Galba, E. iv. f. 185. In the Register of benefactors of St. Albans, Nero, D. viii. f. 87, Thos. de Hatfelde, Bp. of Durham, 1345, is represented holding his gift in his hands, namely, a covered mazer, “cyphum suum murreum, quem Wesheyl nostris temporibus appellamus.” A maser very similar in form, but without a cover, was in the possession of the late John Gage Rokewode, Esq. It is of knotty, dark-coloured wood, mounted with metal: on the small plate, termed crusta, attached to the bottom, is graven the monogram IHC. and around the brim the following couplet:

“+Hold” owre tunge, and sey þe best,

and let “owre ney“bore sitte in rest:

Hoe so lustyþe god to plese,

let hys ney“bore lyue in ese.”

Similar instances of masers bearing inscriptions may be found in Testam. Ebor. i. 209, and Richard's Hist, of Lynn, i. 479. Doublet, in his Hist. of St. Denis, describes the richly-ornamented “hanap de bois de mardre,” which had been used by St. Louis, and presented to that church. “Vermiculatus, variatus ad modum vermis, distinctus, rubeus, maderde.” Med. “Madré, of wood whose grain is full of crooked and speckled streakes, or veins.” Cotg. Plantin, in the Flemish Dict. 1573, gives “Maser, un næud ou bosse à un arbre nommée erable. Maseren hout, acernum lignum.” In Syre Gawene and the Carle a lady's harp is described, formed “of masere fyne,” v. 433, which Sir F. Madden explains to be the wood of the maple. See on the manufacture of “hanas de madre” the Reglements sur les métiers de Paris au XIII. siècle; Documents inédits sur l'histoire de France, p. 112 edited by Depping. Compare Ronnyn, as masere, or other lyke, hereafter.

page 328 note 3 “Lepra, quedam infirmitas, meselrye. Leprosus, mesell, or full of lepre.” Ortus. It appears that, though this term was frequently used as synonymous with leprosy, they were sometimes considered as distinct. See Roquefort, v. Mesel. R. Brunne calls the leprous Baldwin, King of Jerusalem, “þe meselle,” and states that for “foule meselrie he comond with no man.” Langt. Chron. p. 140. In the earlier Wicliffite version the Syrian Naaman, iv. Kings, c. 5, and the four lepers in Samaria, c. 7, are called “mesels.” See also Sir Tristrem, p. 181; Vis. of Piers P. v. 1624, 4689, and 11,024; Chaucer, Personea T. &c. “A meselle, serpedo.” Cath. ang. “Mesyll, a sicke man, meseav. Mesyll, the sickenesse, mesellerie.” Palsg. “Meseau, a meselled, scurvy, leaporous, lazarous person.” Cotg. See Weber's notes on Amis and Amiloun, and Jamieson.

page 329 note 1 Masty signifies swine glutted with acorns or berries. A.-S. mæste, esca, baccæ.

“Ye mastie swine, ye idle wretches,

Full of rotten slow tetches.” Chaucer III. B. of Fame.

“Masty, fatte, as swyne be, gras. Maste for hogges, novriture à povrceaux. Acorne, mast for swyne, gland. Many a falowe dere dyeth in the wynter for faulte of maste (mast), and that they haue no yonge springes to brouse vpon.” Palsg. Compare Mestyf, hogge, or swyne; and Fat fowle, or beste, mestyde to be slayne, p. 151.

page 329 note 2 “Mattefelone, Jacea, herba est.” Cath. ang. It is said in a Treatise on the virtues of herbs, Roy. MS. 18 A. VI. f. 78, vº. that “Jasia nigra ys an herbe þat me clepyþ maudefelune, or bolwed, or yrychard, oþer knoppewede : þys herbe haþ leuys ylyke to scabyose, and þys herbe haþ a flour of purpul colour.” In the Synonymia of herbs, Sloane MS. 5, is given “Jacea nigra, Gall, madfeloun, Ang. snapwort.” Gerard mentions the English names knap-weed, bull-weed, and matfelon; also materfillon, or matrefillen. It is the Centaurea nigra, Linn. Parkinson affirms that this plant is called “matrefillon very corruptly from Aphylanthes,” because the flowers are leafless; and Skinner suggests that from its scabrous nature it is suited to scourge felons withal. Belg. matteu, fatigare. Cow-wede is again mentioned hereafter, under the word Oculus christi.

page 330 note 1 In Norfolk, according to Forby, the smaller thrush only, Turdus musicus, Linn. is called mavis. The name is used by Chaucer, R. of Rose, 619; and Spenser,

“The Thrush replyes, the Mavis descant playes.” Epithal. 81.

“Maviscus, ficedula, mawysse.” Roy. MS. 17 C. XVII. “Mauys, a byrde, mavuis.” Palsg. “Mauvis, a Mavis, a Throstle, or Thrush.” Cotg. See Jamieson.

page 330 note 2 It is evident that the name of Mahomet became, as in old French, a term denoting any idol; as also mahomerie, in low Latin mahomeria, was used to signify the worship of any false deity. Amongst the charges brought by the King of France against Pope Boniface VIII. one was that he “haunted maumetrie.” Langt. Chron. p. 320. In the version of the Manuel des Pecches, R. Brunne uses the word, speaking of a “prest of Sarasyne,” who lived in “maumetry.” Harl. ms. 1701, f. 2. See also R. Glouc. p. 14; Chaucer, Cant. T. 4656; Persone's T. p. 85; the Wicliffite version, i. Cor. xii. 2; i. John, v. 21; and the relation of the conversion of King Lucius in Hardyng's Chron. Hall calls Perkin Warbeck the Duchess of Burgundy's “newly-invented mawmet,” and speaks of him as the “feyned duke—but a peinted image.” The circumstance that this name was applied to him is shown likewise by the passage in Pat. 14 Hen. VII. 1498, regarding the punishment of those persons in Devon and Cornwall who “Michaeli Joseph rebelli et proditori nostro, aut cuidam idolo, sive simulacro, nomine Petro Warbek, infimi status viro, adhæserint.” Rymer, xii. 696. So also Fabyan, relating the insurrections at Paris and Rouen in 1455, says that the men of Rouen “made theym a mamet fatte and vnweldy, as a vylayne of the cytye, and caryed him about the towne in a carte, and named hym, in dyrysyon of theyr prynce, theyr kynge.” Chron. Part VII. 7 Charles VII. “Chamos, a mawmett. Pigmeus, a mawmett, or a fals mawmetrye, cubitalis est.” Med. ms. cant. “A mawmentt, idolum, simulachrum. Mawmentry; a mawment place; a mawment wyrscheper,” &c. Cath. ang. “Simulachrum—a mawmet, or an ydoll.” Ortus. “Maumentry, baguenaulde. Maument, marmoset, poupee.” Palsg. “A maumet, i. a child's babe.” Gouldman. See Mawment in Brockett, and the Craven Dialect.

page 330 note 3 “Mawnde, ubi mete vesselle (escale.)” Cath. ang. Caxton says, in the Book for Travellers, “Ghyselin the mande maker (corbillier) hath sold his vannes, his mandes (corbilles) or corffes.” “Manne, mande, a maunde, flasket, open basket, or pannier having handles.” Cotg. This word is given by Ray, as used in the North, and noticed likewise in the Craven Dialect. It is commonly used in Devon: see Palmer's Glossary. Ang.-Sax. mand, corbis. It seems, as Spelman has suggested, that the Maunday, or dole distributed on Holy Thursday, derived its name from the baskets wherein it was given, and not from the Latin mandatum, in allusion to the command of Christ, or from the French mendier. See a full account of the customs on this occasion in Brand's Popular Antiquities. “Maundy thursday, ievuedy absolv.” Palsg.

page 331 note 1 From the alphabetical position, it appears that Maye should here be read Maþe. In the Treatise of fishing with an Angle, in the St. Alban's Book, the following are given as baits for roach in July: “The not worme, and mathewes, and maggotes, tyll Myghelmas.” Sign. i. ij. Ang.-Sax. maða, vermis. In the Northern Dialect a maggot is called a mauk; see Brockett, Craven Glossary, and Jamieson. “A mawke, cimex, lendex, tarmus. Mawky, cimicosus, tarmosus.” Cath. ang. “Tarmus, simax, a mawke.” Roy. MS. 17 C. XVII. “Tarma, vermis bladi, a mawke.” Ortus.

page 331 note 2 It is not clear whether this is to be considered as an obsolete and local name for the mackarel, megarus having been previously given as the Latin name for that fish; see p. 321. The Maigre, Sciæna aquila, Cuv. Umbra Rondeletii, Willughby, the celebrated delicacy of the Mediterranean, is a wandering fish, which occasionally has been taken on the coasts of Britain; but the name here seems to be rather a corruption of the Latin, than derived from the French maigre. See that word in Cotgrave.

page 332 note 1 This term, derived from the French maisnie or magnie, a family, troop, or the suite of a great personage, in low Latin maisnada, or mansionata, is very frequently used by the old writers. Thus in the Wicliffite version, Job i. 3 is thus rendered: “His possessioun was seuene thousand of shep—and ful meche meyne” (familia multa nimis, Vulg.) See also R. Glouc. pp. 167, 180; Tyrwhitt's Glossary appended to Chaucer, and his curious observations on “Hurlewaynes meyne.” Sir John Maundevile relates how the Great Chan, Changuys, riding “with a fewe meynee,” was assailed by a multitude of his foes, and unhorsed, but saved by means of an owl. Voiage, p. 271. The term is used also to signify the set of chess-men, called in Latin familia, as in the Wardrobe Book 28 Edw. I. p. 351: “una familia pro scaccario de jaspide et cristallo.” R. Brunne, in his version of Wace's description of the Coronation of Arthur, says that some of the courtiers “drew forth meyné of the chequer.” Caxton, in the Book of Travellers, says, “Grete me the lady or the damyselle of your hous, or of your herborough, your wyf, and all your meyne (vostre maisnye.)” “A men“e, domus, domicilium, familia.” Cath. ang. Horman says, “I dare not cople with myn ennemyes, for my meyny (turmæ) be sycke and wounded. A great meny of men can nat ones wagge this stone. Here cometh a great meny (turba.)” Palsgrave gives “Meny, a housholde, menye. Meny of plantes, plantaige. Company, or meyny of shippes, flotte. After a great shower of rayne you shal se the water slyde downe from the hylles, as thoughe there were a menye of brokes (vng tas de ruisseauw) had their spring“ there.”

page 332 note 2 Menlte, ms. menkte, K. s. p. menged, W. Gouldman gives the verb “to mein, vide mingle.” Ang.-Sax. men“an, miscere.

page 333 note 1 “Aforus est piscis, a menuse.” Med. See the Equivoca of John de Garlandia, with the interpretations of Magister Galfridus, probably the same as the compiler of the Promptorium, where it is said “Mena est quidam piscis, Anglice a penke, or a menew penke, sic dictus a mena, Grece, quod luna Latine; quia secundum incrementum et decrementum lune singulis mensibus crescit et decrescit.” Ed. Pynson, 1514. The minnow is still called pink in Warwickshire, and some other parts of England; see also Plot's Hist. Oxf. and Isaac Walton. Gouldman gives “pisciculi minuti, small fishes called menews or peers.”

page 333 note 2 Gautier de Bibelesworth speaks of “mercurial de graunt valur,” where the English name, given in the Gloss, is “smerewort.” The ancient herbalists are diffuse in their accounts of the virtues of this plant: it is stated by Dioscorides and other writers that the species mariparum and fæminiparum produced the effect of engendering male or female children.

page 333 note 3 In Norfolk, according to Forby, a Mara-balk, or mere, is a narrow slip of unploughed land, which separates properties in a common field. “Limes est callis et finis dividens agros, a meere. Bifinium, locus inter duos fines, a mere, or a hedlande.” Med. ms. cant. “A meyre stane, bifinium, limes.” Cath. ang. In a decree, t. Hen. VI. relating to Broadway, Worcestershire, printed by Sir Thomas Phillipps, part of the boundaries of Pershore Abbey is described as the “mere dyche.” In the curious herbal, Arund. MS. 42, f. 55, it is said that “Carui—groweþ mykel in merys in þe feld, and in drye placys of gode erþe.” In Sir Thos. Wharton's Letter to Hen. VIII. in 1543, regarding the preservation of peace in the North country, is the recommendation “that all the meir grounddes of Yngland and Scotland to bee certanely knowne to the marchers, the inhabitauntes of the same.” State Papers, v. 309. The verb to mere, to have a common boundary, occurs in another document, printed in the same collection; see the Glossary in vol. ii. Leland relates, Itin. vi. p. 62, that “Sir John Dicons told me that yn digging of a balke or mere yn a felde longgyng to the paroche of Keninghaul in Northfolk ther were founde a great many yerthen pottes yn order, cum cineribus mortuorum.” Elyot gives “terminalis lapis, a mere stone, laide or pyghte at the ende of sundry mens landes. Cardo, mere, or boundes which passeth through the field.” The following words occur in Gouldman : “To cast a meer with a plough, urbo. A meer, or mark, terminus, meta, limes. A meer stone, v. Bound.” Ang.-Sax. meare, finis.

page 334 note 1 “Mere sauce for flesshe, savlmure.” Palsg. The Anglo-Saxon name for pickle, or brine, was morode; in old French mure. “Saulmure, pickle, the brine of salt; the liquor of flesh, or fish pickled, or salted in barrels, &c.” Cotg.

page 334 note 2 See the note on the word Dole, p. 126.

page 334 note 3 See the note on the word Mast hog, or mastid swyne, according to the reading of the Cambridge MS. In the Catholicon maialis is explained to be “porcus domesticus et pinguis, carens testiculis;” to which is added in the Ortus, “a bargh hogge.” The Winchester MS. agrees here in the reading Mestyf, otherwise it might have been conjectured that it should have been written Mestyd hogge; the derivation in either case being apparently from the Ang.-Sax, mæstan, saginare. Skinner supposes that the word mastiff, denoting a dog of unusual size, is also thence derived; but it seems more probable that it was taken from the old French mestif, which, according to Cotgrave, signified a mongrel. In the Craven Dialect a great dog is still called a masty.

page 334 note 4 Meslin-bread, made with a mixture of equal parts of wheat and rye, was, according to Forby, formerly considered as a delicacy in the Eastern counties, the household loaf being composed of rye alone. The mixed grain termed maslin is commended by Tusser. It was used in France in the concoction of beer, as appears by the regulations for the brewers of Paris, 1254, who were to use “grains, c'est à savoir, d'orge, de mestuel, et de dragée.” Reglements, t. Louis IX. ed. Depping, p. 29. In 1327, it appears by the almoner's accounts at Ely that five quarters of mesling cost 20s. and two quarters of corn 9s. 4d. Stevenson's Supp. to Bentham, p. 53. In 1466 Sir John Howard paid, amongst various provisions for his “kervelle” on a voyage to “Sprewse, for a combe of mystelon, ij.s. vj.d.” Household Expenses, presented to the Roxburghe Club by B. Botfield, Esq. p. 347. See also a letter, about 1482, in the Paston Correspondence, V. 292. In the Inventory of Merevale Abbey, taken in 1538, occurs “grayne at the monastery, myskelen, xij. strykes.” At the dinner given in 1561 to the Duke of Norfolk by the Mayor of Norwich, there were provided “xvj. loves white bread, iv.d. xviij. loves wheaten bread, ix.d. iij. loves mislin bread, iij.d.” Leland, Itin. vi. xvij. Caxton says, in the Book for Travellers, that “Paulyn the meter of corne hath so moche moten of corne and of mestelyn (mestelon) that he may no more for age.” Plot states that the Oxfordshire land termed sour is good for wheat and “miscellan,” namely, wheat and rye mixed. Hist. Oxf. p. 242. In the Ortus, mixtilio is rendered “medeled corne;” in Harl. MS. 1587, “mastcleyne.” “Mastil“one, bigermen, mixtilio.” Cath. ang. Palsgrave gives “mestlyon corne,” and “masclyne corne;” and Cotgrave “Tramois, meslin of oats and barlie mixed. Meteil, messling, or misslin, wheat and rie mingled, sowed, and used together.” See Dragge, menglyd corne, p. 130.

page 335 note 1 “A mette, mensura, metreta, et proprie vini, metron Grece.” Cath. ang. “Amona dicitur calamus mensure.” Ortus. In the Northern Dialect met still signifies a measure. See Scantlyon, or scanklyone. Equissium.

page 335 note 2 — for evene, MS. Mete or evyn, K.

page 335 note 4 Medycyne, MS. metecyne, H. s.

page 335 note 4 Cubitum, MS. In the Medulla cibutum is rendered “a mete whycche.” See Almery, p. 10. Possibly the long chest, such as is frequently termed a bacon-hutch, is here intended, as it might serve also the purpose of a bench; Ang.-Sax. setl, sedile. A settle is, however, properly the high-backed bench placed near the fire. See Forby.

page 336 note 1 Stowe asserts that Hen. I. reformed the measures, and fixed the ulna by the length of his own arm, “and now the same is called a yard, or a metwand.” “A meat-wand, virga.” Gouldman. “A meate-wand, verge par le moyen de laquelle on mesure quelque longueur ou distance.” Sherwood. In Levit. xix. 35, mensura, Vulg. is rendered, in Coverdale's Bible, a “meteyarde.” Ang.-Sax. met-ʓeard. Palsgrave gives the verb, “I measure clothe with a yerde, or mette yerde.”

page 336 note 2 Tapax, MS. as also Mychery, Tapacitas, and Mychyñ, Tapio. A mychare seems to denote properly a sneaking thief. Gower thus describes secretum latrocinium;

“With couetise yet I finde

A seruant of the same kinde,

Which stelth is hote, and micherie

With hym is euer in company.”

See also Towneley Myst. pp. 216, 308, and the Hye way to the Spyttell house.

“Mychers, hedge crepers, fylloks and luskes,

That all the somer kepe dyches and buskes.” Ed. Utterson, ii. 11.

It signifies also one who commits any sneaking, mean, or miserly act: and, according to Nares, a truant. Horman says, “He strake hym through the syde with a dager, and ranne away like a mycher (latibundus aufugit.) He is a mychar (vagus, non discolus;) a rennar awey or a mychar (fugitivus.)” “Micher, a lytell thefe, larronceav. Michar, bvissonnier.” Palsg. “Dramer, to miche, pinch, dodge, to use, dispose of, or deliver out things by a precise weight, as if the measurer were afraid to touch them, &c. Vilain, a churle, also a miser, micher, pinch pennie, penny father. Senaud, a craftie Iacke, or a rich micher, a rich man that pretends himselfe to be very poore. Caqueraffe, a base micher, scuruie hagler, lowsie dodger, &c. Caqueduc, a niggard, micher,” &c. Cotg. “To mich in a corner, deliteo. A micher, vide Truant.” Gouldm. Tusser uses the term micher, which is not given in the East-Anglian Glossaries.

page 336 note 3 Chaucer uses the term mitche, R. of Rose, 5585, where it is explained by Tyrwhitt as signifying a manchet, a loaf of fine bread. The old French word miche, and Latin mica, or michia, signify, according to Roquefort and Ducange, a small loaf. “Mica ponitur pro pane modico qui fit in curiis magnatorum vel in monasteriis.” Cath. Hearne gives in the notes to the Liber Niger, p. 654, a quotation from the Register of Oseney, 52 Hen. III, wherein mention occurs of magnæ michiæ;, of the bisa and sala michia; and Spelman cites a document which describes “albos panes, vocatos michis.” In 1351 Robert, Abbot of Lilleshall, granted “viij. magnas micas majoris ponderis de pane conventus” to Adam de Kaukbury; and a corrody is enregistered in the Leiger Book of Shrewsbury Abbey, by which Abbot Lye granted, in 1508, to his sister, “viij. panes conventuales vulgariter myches vocatos,” &c. Blakeway's Hist. ii. 129. Mychekyne seems to be merely a diminutive. “Pastilla, a cake, craknell, or wyg.” Ortus.

page 337 note 1 A distinction is here made in Pynson's and the other editions of the Promptorium. Mychyn. Manticulo. Mychyn, or stelyn pryuely. Surripio, clepo, capaxo.

page 337 note 2 The reading of the Winch. MS. is Myddyl, or dongyl, so termed possibly from its position in the fold-yard. In the North the Ang.-Sax. middinₓ, sterquilinium, is a term still in use, as in the Towneley Myst. p. 30. “Fumarium, myddyng.” Roy. MS. 17 C. XVII. “A middynge, sterquilinium.” Cath. ang. The following lines occur in a poem, where man is exhorted to contemplate heaven and hell, the world, and sin :

“A fuler mydding of vilonie,

Saw thou neuere in londe of pes,

Than thou art with in namely,

Than hastow matere of pride to cesse.” Add. MS. 10,053, p. 146.

page 337 note 3 “Emigraneus, vermis capitis, Anglice the mygryne, or the hede worme.’ Ortus. “þe emygrane, emigraneus. þe mygrane, ubi emigrane.” Cath. ang. “Migrym, a sickenesse, chagrin, maigre.” Palsg. Remedies are given in Arund. MS. 42, f. 105, vº.

page 338 note 1 See Bengere of a mylle, p. 31. “Faricapsa, an hoper.” Ortus.

page 338 note 2 “I mente, I gesse or ayme to hytte a thynge that I shote or throwe at, Ie esme. I dyd ment at a fatte bucke, but I dyd hyt a pricket.” Palsg. Forby gives “mink, mint, to attempt. Alem. meinta, intentio.” See Brockett's Glossary, and Jamieson, v. mint, signifying to aim at, to have a mind to do something. Ang.-Sax. myntan, disponere.

page 338 note 3 Minera, according to Joh. de Garlandiâ, is a vein of ore, a mine; or, as Upton uses the word, a mine formed during a siege. Mil. Off. i. c. 3.

page 338 note 4 Chaucer, in the Miller's Tale, puts the following taunt into the mouth of the Smith, who awakes Absolon, bidding him seek vengeance for the ill success of his amour:

“What eileth you? some gay girle, God it wote,

Hath brought you thus on the merytote.” Cant. T. 3768.

Tyrwhitt prints this line—“upon the viretote.” Speght, in his Glossary, explains the word as signifying a swing, oscillum, suspended from a beam for the amusement of children. Strutt mentions the meritot, or merry trotter, in his Sports and Pastimes, p. 226, and in the Orbis Sensualium of Comenius it is given under the sports of boys, who are represented “swinging themselves upon a merry-totter, super petaurum se agitantes et oscillantes.” Ed. Hoole, c. cxxxvj. Skinner gives this word on the authority of the Diction. Angl. 1658, and supposes it to be of French derivation, from virer and tost, quickly. In the Cath. ang. the word is twice given, under the letter M. “A Merytotyr, oscillum, petaurus;” and again under the letter T. “A mery Totyr, petaurus, etc. ubi a mere totyr.” Palsgrave gives “Tyttertotter, a play for chyldre, balenchoeres.” See the Craven Glossary, v. Merry-totter, and Brand's Popular Antiqu. See hereafter Totyr, or myry totyr, and the verb Wawyñ, or waueryn yn a myry totyr, oscillo. According to Forby to titter, or titter-cum-totter, signifies in Norfolk to ride on each end of a balanced plank.

page 339 note 1 Merry is not infrequently used by the old writers in the sense of pleasant. Ang.-Sax. myriʓ, jucundus. In the version of Vegecius, attributed to Trevisa, Roy. MS. 18 A. XII. it is observed that wise warriors in olden times used to “occupie theire foot menne in dedes of armes in the felde in mery wedire, and vndre roof in housing in fowle wedre.” B. iii. c. 2. Again, precaution is recommended at sea against unsettled weather, and the diversity of places, “the whiche maketh ofte of mery wedre grete tempestes, and of grete tempestes mery weder and clere.” B. iv. c. 38. The arms borne by the name of Merewether are to be classed with the armoiries parlantes; namely, Or, three martlets sable, on a chief azure a sun in splendour; the martlet being, as it was supposed, an omen of fair weather.

page 339 note 2 This word occurs in Brunne's version of Langtoft, p. 176; Chaucer's Rom. of R. v. 5339; the Vis. of Piers Ploughman; Awntyrs of Arthure, 68; Towneley Myst. p. 167. In a description of hell, in Add. MS. 10,053, p. 136, the following passage occurs:

“Synne shal to endeles payne the lede

In helle, that is hidous and merke.—

Ther is stynk, and smoke a-mong,

And merkenesse, more than euer was here.”

“Mirke, ater, caliginosus, fuscus, obscurus, umbrosus. A mirknes, ablucinacio, i. lucis alienacio, chaos, &c. To make or to be mirke, tenebrare, nigrere.” Cath. ang. “Myrke, or darke, brun, obscur. I myrke, I darke, or make darke (Lydgat), Ie obscurcys.” Palsg. See Brockett, Craven Glossary, and Jamieson. Ang.-Sax. mirc, tenebræ. See Therke, hereafter.

page 339 note 3 This term apparently denotes crumbs or grated particles of bread, called in French mies, or mioches. “Mica, religuie panis, vel quod cadit de pane dum frangitur et comeditur, &c. a crome of brede.” Ortus. In the Book of Cookery, written 1381, and printed by Pegge with the Forme of Cury, it is directed to take onions, “and myce hem ri“t smal,” as also to “myse bred,” &c. pp. 93, 95. The participle “myyd” occurs in Sloane MS. 1986, f. 85, and other passages, and signifies grated bread, which, as it has been observed in the note on the verb Grate, p. 207, was much used in ancient cookery.

page 340 note 1 “A mister, ubi a nede. A nede, necessitas, necesse, opus,” &c. Cath. ang. Roquefort gives the following explanation of the French word, whence this appears to be taken: “Mester, mestier: besoin, nécessaire,” &c. Chaucer uses the word “mistere,” signifying need, as of daily food, in the comparison between the wealthy miser and the poor man; R. of Rose, v. 5614; and again, in the sense of requiring the services of any one; see the address of Love to False Semblant, ib. v. 6078. See Towneley Myst. pp. 90, 234, and Jamieson, v. Mister.

page 340 note 2 The position of this word in the alphabetical arrangement would indicate that the reading of the Cambridge MS. is here to be preferred. Mynute was, however, used synonymously with mite, as appears by the passage in the Wicliffite version, Mark xii. 42, quoted in the note on Cu, halfe a farthynge, p. 106. Gouldman gives “a minute, or q. which is half a farthing, minutum.” It is said in the Ortus, “minutum est quoddam genus ponderis, scilicet media pars quadrantis;” and a distinction appears to be made in the following citation: “A myte, mita: a myte, quod est pondus, minutum.” Cath. ang. Palsgrave gives “myte, the leest coyne that is, pite,” which was a little piece struck at Poitiers, Pictavina, and of the value of half an obole; and Sherwood renders “Mite (the smallest of weights, or of coine) Minute; aussi, vne petite piece de monnoye non vsitée.” There is no evidence that any coin of such value was ever struck in England, but small foreign pieces may have been circulated, such as the Poitevine, or the “dyner of Genoa,” which also, according to R. Holme, was worth half a farthing. Acad. of Arm. B. iii. c. 30. Roquefort explains mite as signifying a Flemish copper coin; but, according to Ducange, the value of the Flemish mita was four oboli. It is, however, possible that fractional parts of the silver penny or farthing might occasionally pass as mites: thus entries frequently occur in the Accounts of the Keeper of St. Cuthbert's Shrine, during the XVth cent. as cited by Raine, respecting “fracta pecunia;” and the petition of the Commons in 1444, 23 Hen. VI. complains of the great injury that arose from the division of coin, for want of small currency, and craves that the breaking of white money be forbidden under a heavy penalty. Rot. Parl. V. 109.

page 340 note 3 “Mita est pilum frigium, or a myttane. Mantus, a myteyn, or a mantell.” Ortus. “A mytane, mitta, mitana.” Cath. ang. In the curious dictionary of John de Garlandiâ it is said that “cirothecarii decipiunt scolares Parisius (sic) vendendo cirothecas simplices, et furratas pellibus agninis, cuniculinis, vulpinis, et mictas de corio factas.” The following explanation is given in the gloss: “Mitas, Gallice mitanes (mitheines, al.) a mitos, quod est filum, quia primo fiebant de filo vel de panno laneo, et adhuc fiunt a vulgo.” MS. Bibl. Rothom. It is said in the Catholicon that “a manus dicitur mantus, quia manus tegat tantum, est enim brevis amictus,” &c. the primary sense of this Latin term being a short garment or mantle. In the minute description of the garb of the Ploughman are mentioned his “myteynes ” made of cloutes, with the fingers “for-werd,” or worn away; see Creed of Piers P. v. 851. Amongst the feigned miraculous gifts whereby the Pardoner in the Cant. Tales states that he turned to account the credulity of his hearers, one was a mitaine:

“He that his hand wol put in this mitaine,

He shal have multiplying of his graine.” Cant. T. v. 12307.

In 1392 Rich. Bridesall, merchant, of York, bequeaths “meum magnum dowblet, et meum mytans de d'orre, et meum dagardum.” Test. Ebor. i. p. 174

page 341 note 1 This verb is placed in the MSS. as likewise in the printed copies, between Moorderyñ and Moryñ. “I modefye, I temperate, Ie me modifie, and Ie me trempe. What thoughe he speke a hastye worde, you muste modyfye your selfe.” Palsg.

page 341 note 2 The term mauther has been recognised as peculiarly East-Anglian by Sir Thos. Browne, Spelman, Forby, and Moor. It is used by B. Jonson. Tusser, in his list of husbandly furniture, includes “a sling for a mother (moether, al. ed.) a bow for a boy,” intended for driving away birds, as he advises, in September's husbandry, to set “mother or boy “to scare away pigeons and rooks from the newly-sown land, with loud cries, sling, or bow. “Puera, a woman chylde, callyd in Cambrydge shyre a modder. Pupa, a yonge wenche, a gyrle, a modder.” Elyot. “Baquelette, a young wench, mother, girle. Fille, a maid, girle, modder, lasse,” &c. Cotg. “A modder, fillette,jeune garse, garsette.” Sherw. “A modder, wench or girl, puera, pupa.” Gouldm. Compare False modder, or wenche, p. 148. Dan. moer, Belg. modde, puella.

page 341 note 3 Possibly the correct reading should here be Mocke, or mowe. See Mowe, or skorne.

page 341 note 4 See the account of funeral entertainments in Brand's Popular Antiquities. Wine or ale sweetened and spiced was termed mulled, as Skinner supposes, from the Latin mollitum; but more probably from the mulled or powdered condiments essential to the concoction. Compare Mullyn, or breke to powder. “Molle, “pulver,”.&c. Cath. and. Island, mil, in minutas partes tundo; prœter, mulde.

page 342 note 1 Mone, ms. Compare Teut. moeme, Germ, muhme, matertera.

page 342 note 2 “Sichofanta, i. falsus calumniator, vel vilium rerum appetitor.” Cath. “Maunche present, briffavlt. I manche, I eate gredylye. Are you nat ashamed to manche (briffer) your meate thus lyke a carter ? I monche, I eate meate gredyly in a corner, ie loppine,” &c. Palsg. Bp. Kennett gives “to munge, to eat greedily; Wilts.” Lansd. MS. 1033. “A maneh-present, dorophagus.” Gouldm. “Brifaut, a hasty devourer, a fast eater, a ravenous feeder, a greedy glutton.” Cotg.

page 342 note 3 Moppe signifies here a child's doll, formed of rags, as Popyn is explained hereafter to be a “chylde of clowtys.” Nares gives it as a term of endearment to a girl, as moppet is used in Suffolk, according to Moor. “A little mopse, puellula.” Gouldm. In the Sevyn Sages, v. 1414, the foolish burgess who went from his home to seek a wife is said to have gone forth “as a moppe wild,” where the word is explained by Weber as signifying a fool.

page 343 note 1 This comparative frequently signifies large dimension, and not number. Thus in Kyng Alis. v. 6529, the rhinoceros is described as “more than an olifaunt;” and in the Wicliffite version it is used to express superior, by priority of birth; where it is said that Isaac knew not Jacob, “for þe heery hondis expressiden þe licnesse of þe more son.” Gen. xxvii. 23. In the Version of Vegecius, Roy. MS. XVIII. A. 12, the heavy-armed troops are said to have had two kinds of darts, “one of the more assise, the other of the lasse;” the “pile,” which measured 5½ feet in length, and the “broche,” which was shorter by two feet. So likewise in the Golden Legend the “more letanye,” on St. Mark's day, is distinguished from the “less letanye, iij. days to fore the Ascension.” It is occasionally retained in names of places, as More Critchill, Dorset, probably so called by way of distinction from Long Critchill, and other neighbouring hamlets. The rebus, or canting device of the Mortons of Bushbury, Herefordshire, repeatedly used amongst the ornaments of the chantry founded by one of that family on the south side of the church, is a tun inscribed with the initial of his Christian name, the syllable Mor being, as it would seem, expressed by the supposed dimension of the tun, or its proportion to the scutcheon whereon it is placed.

page 343 note 2 Morellus is explained by Ducange as meaning subfuscus; so likewise Roquefort gives “morel; noir, tanné, tirant sur le brun.” According to Cotgrave cheval morel is a black horse. In the Towneley Mysteries, p. 9, “Morelle” occurs as the name of one of the horses yoked to Cain's plough.

page 343 note 3 Gower describes the glowing blush which restored beauty to the features of Lucrece, on meeting her husband, “so that it myght not be mored.” Conf. Am. vii. In the curious metrical version of the most ancient grants to St. Edmund's Bury, preserved in the Register of Abbot Curteys, the following lines occur in the Charter of Canute :

“Bexample of whom (St. Edmund) I Knut am gretly mevyd,

To the holy martyr I wyl that al men se,

That his chirche be fraunchised and relevyd,

Moryd and encresyd as fer as lyth in me.”

Horman, amongst the passages from Terence, gives the following: “He dredith lest thy olde angyr or hardnes be mored or incresyd.”

page 343 note 4 Compare Ang.-Sax. morʓan-ʓifu, dos nuptialis. In La“amon “mor“eue “occurs in this sense, ed. Madden, iii. 249, and “mœr“eue ” ii. 175, which is in Wace's original “douaire.” See Hickes, Thes. i. p. ix. Pref. and Wachter, v. Morgengabe.

page 343 note 5 Chaucer, in the Prologue to Cant. T. v. 388, describes the Cook as afflicted with “a mormal,” or gangrene on his shin, called in Latin malum mortuum, and in old French mauxmorz. Remedies for the mortmal may be found in Arund. MS. 42, f. 105, V°; and in Sloane MS. 100, f. 58, vº, a compound is described of litharge of gold, oil of roses, white wine, old urine, &c. which formed “a plastre þat William Faryngdoun kny“t lete a squyer þat was his prisoner go quyt of his raunsum fore. This plastre wole hele a mormal, and cancre, and festre, and alle oþere sooris.” Caxton says, in the Book for Travellers, “Maximian the maistre of phisike can hele dropesye, blody flyxe, tesyke, mormale (mormal.)” “Mormall, (or marmoll,) a sore, lovp.” Palsg.

page 344 note 1 This term denoted a periodical assembly of a gild : A.-Sax. morʓen-spsæc. See Hickes, Thes. ii. 21, i., ix., and extracts from Registers of gilds at Lynn, Richards' Hist. pp. 422, 477.

page 344 note 2 “Mortrewes” occur amongst the dishes mentioned by Chaucer in the account of the Cook's abilities; Cant. T. Prol. v. 386. “Mortrws, pepo, peponum.” Cath. ang. “Pepo, i. melo, mortrews, et est similis cucurbite.” Ortus. Mortrews, according to various recipes given in Harl. MS. 279; Cott. MS. Jul. D. viii. and Sloane MS. 1986, seems to have been fish, or white meat ground small, and mixed with crumbs, rice flour, &c. See in the last mentioned compilation “mortrews de chare, blanchyd mortrews, and mortrews of fysshe,” pp. 55, 60, 66, given under the head de potagiis. The term is frequently written “morterel, mortrewys,” &c. and is possibly derived from the mode of preparation, by braying the flesh in a morter. “Mortesse meate.” Palsg.

page 344 note 3 Many instances might be cited of the use of the word morrow, signifying the morning, as Chaucer uses it, when he says of the Frankelein, “wel loved he by the morwe a sop in win.” Cant. T. 335. Sir John Maundevile speaks of the idolatry of the natives of Chana, who worshipped a serpent, or whatever animal “that thei meten first at morwe.” In the Version of Vegecius, Roy. MS. XVIII. A. 12, it is said that it is requisite to ascertain the custom of the enemy, “if they be wonede to assaile or falle vpone the nyghte, or in the morow.” B. iii. c. 6. In the curious translation of Macer's treatise on the virtues of plants, MS. in the possession of Hugh Diamond, Esq. it is observed that “he þat etiþ caule (brassica) first at morwe, vnnethe shal he fynde drunkenesse þat day.” The day-star likewise is called the Morow sterre. In the Golden Legend it is said of the Assumption of our Lady that an angel brought her “a bowe of palme, whose leues shone lyke to the morowe sterre.”

page 344 note 4 This term is taken from the French mot, which is explained by Nicot to imply “le son de la trompe d'un Veneur, sonné d'art et maistrise.” See Twety, Vesp. B. xii. f. 4; R. Holme, Acad. of Arm. iii. p. 76. Horman says that “blowyng of certain and diuers motis, and watchis, gydeth an host, and saueth it from many parellys. The trompettours blowe a fytte or a mote (dant classicum).” “Mote, blast of a home.” Palsg.

page 345 note 1 “To mute, allegare, ut ille allegat pro me; causare, contraversari, decertare, placitare. A mute halle, capitolium. A muter, actor, advocatus, causidicus, &c. Mutynge, causa, pragma.” Cath. ang. “Mote or encheson, causa, causale, litigium.” Vocabulary, Harl. MS. 1587. “Causa, a cause or motynge. Causarius, a pledere, a motere. Causor, to plede or mote.” Med. “Certamen, i. pugna vel litigium, a chydynge or motynge. Controversor, to mote, plede, or chyde.” Ortos. Ang.-Sax. mot, conventus, motian, to meet for the purpose of discussion, disputare; mot-hus, or moð-heal, a place of meeting. In the poem on the evil times of Edw. II. Polit. Songs, p. 336, complaint is made of the corruption of Justices, and other legal authorities, who, instead of fair and open dealing, “maken the mot-halle at hom in here chaumbre.” In the Wicliffite version, John xviii. 28, prætoriurn is rendered “moot-halle.” See also Vis. of Piers P. v. 2352. Compare Plee, of motynge.

page 345 note 2 In the Winch. MS. Rere is given hereafter as synonymous with Mothe woke. This appears to be a compound word, the last syllable of which may be derived from Ang.-Sax. wác, debilis, flexibilis, whence wác-mod, pusillanimis. The former syllable may possibly be taken from Ang.-Sax. mete, Isl. mot, modus. Hence also “methfulle,” moderate. See Jamieson, v. Meith. Compare lith-wake, or leothe-wok, supple limbed, according to the citations given in the note on the word Lyye, p. 310.

page 345 note 3 Compare A.-S. mæʓ, parens, used very widely to denote a relative, son, sister, niece, &c. See La“amon, i. pp. 12, 73,162, Madden's ed. R. Brunne uses the word “mouh.”

page 345 note 4 “Cachinnor, to grenne, or for to make a mowe.” Med. “To mowe, cachinnare, narire, et cetera ubi to scorne. A mowynge, cachinnatus, rictus.” Cath. ang. “Cachinno, to mowe, or skorne with the mouth.” Ortus. “Mowe, a scorne, move, moe. Mower, skorner, mocquevr. I moo, I mocke, I mowe with the mouthe, ie fays la moue.” Palsg. “Moue, a moe, or mouth; an ill-favoured extension, or thrusting out of the lips. Moüard, mumping, mowing, making mouths. Baybaye, a scornfull moe, or mouth made.” Cotg. “To mow, or mock with the mouth like an ape, distorquere os, rictum deducere.” Gouldm. In the poem on the evil times of Edw. II. a curious picture is given of the “countour,” or barrister, who, pocketing the fee, and speaking a few words to little purpose, as soon as he had turned his back, “he makketh the a mouwe.” Polit. Songs, p. 339. Such scornful gestures were deemed a great breach of good manners; thus, in the Boke of Curtasye, the youth is instructed as to his demeanour at table, where he should especially avoid quarreling, making “mawes,” and stuffing the mouth with food.

“Yf þou make mawes on any wyse,

A velany þou kacches or euer þou rise.—

A napys mow men sayne he makes,

þat brede and flesshe in hys cheke bakes.” Sloane MS. 1986,f. 18, vº.

So also in the like admonition, printed with the title, Stans puer ad mensam, it is said, “grenynge and mowynge at the table eschewe.”

page 346 note 1 “Mought that eateth clothes, uers de drap.” Palsg. Ang.-Sax. moððe, tinea.

page 346 note 2 In Arund. MS. 42, numerous remedies are given for mowles. “Plemina sunt ulcera in manibus et in pedibus callosis, weles or mowles.” Med. “A mowle, pernio.” Cath. ang. This term is taken from the French; “Kybe on the hele, mule.” Palsg. W. Turner, in his Herbal, 1562, speaks of kibes or “mooles,” and says that the broth of rape is good for “kybed, or moolde heles.” Gerard states that “the downe of the reed mace, or cats tail, hath been proved to heale kibed, or humbled heeles (as they are termed) either before or after the skin is broken.” And. Boorde, in the Breviary of Health, c. 272, treats at length of the causes and remedies for such ailments. See Jamieson, v. Mule.

page 346 note 3 “To mowle, mucidare. Mowled, mucidus. Mowlenes, glis, mucor, mussa.” Cath. ang. “Mucor, to mowle as bredde.” Ortus. Palsgrave gives the verb “I mowlde, or fust, as come or breed dothe, Ie moisis,” but the word is usually written, according to the ancient spelling, as given in the Promptorium. Chaucer speaks of “mouled,” or grey hairs. In the relation of a miraculous occurrence given in the Golden Legend, f. 65, vº, it is said, “as the kynge sate at mete, all the brede waxed anone mowly, and hoor, yt no man myght ete of it.” Kilian gives “molen, vetus Flandr. cariem contrahere.” Compare Dan. mulner, to grow mouldy; mulen, hoary or mouldy.

page 346 note 4 “To mughe, posse, valere, queo. To nott moghe, nequire, non posse.” Cath. ang. The verb to mow, to be able, is used by R. Glouc. p. 39, and Chaucer. In the Golden Legend it is said of the last judgment that “the eyghte sygne shall be ye generall tremblynge of the erthe, whiche shall be so grete that noo man ne beest shall not mowe stonde thereon, but fall to the grownde.” Caxton states, in the Book for Travellers, that his intent was “to ordeyne this book, by the whiche men shall mowe resonably understande Frenssh and English, on pourra entendre,” &c. The verb Nowthe mowñ occurs hereafter. Compare Dutch moghen, Germ, moegen, posse.

page 347 note 1 Compare Falle, p. 147. “Paciscolia, i. muscipula, a mowse falle.” Med. ms. cant. In the Shepherd's Calendar it is said that “the couetous man is taken in the nette of the deuil, by the which he leseth euerlasting lyfe for small temporal goodes,— as the mouse is taken in a fall, or trappe (à la ratière, orig.) and leseth his lyfe for a lyttle bacon.” Ed. J. Wally, sign. F. j. vº. Ang.-Sax. mus-fealle, muscipula.

page 347 note 2 “Mowter, vide moulter,—quando avium pennæ decidunt.” Gouldm. To mute or moult, to change the feathers, is taken from the Latin. Palsgrave gives the verb to “mute, as a hauke or birde dothe his fethers, muer ;” which is rendered by Cotgrave “to mue, to cast the head, coat, or skin.” See Ducange, v. Muta. Hence the place where hawks were kept during the change of plumage was termed a mew; and mutare signified to keep them in a mew, as in a document dated 1425, edited by Bp. Kennett, Par. Antiqu.

page 347 note 3 Compare Mwe, or cowle, a coop for keeping or fatting poultry, p. 350.

page 347 note 4 Muggard, in the Exmoor Dialect, signifies sullen and morose. In the sense of avaricious Muglard may be derived from the French “mugotter, to hoord; mugot, a hoord, or secret heap of treasure.” Cotg.

page 347 note 5 The virtues of mugwort, Artemisia vulgaris, Linn, are highly extolled by the ancient herbalists. The following observation occurs in Arund. MS. 42, f. 35, vº. “Mogwort, al on as seyn some, modirwort: lewed folk þat in manye wordes conne no ry“t sownynge, but ofte shortyn wordys, and changyn lettrys and silablys, þey coruptyn þe o. in to u. and d. in to g. and syncopyn i. smytyn a-wey i. and r. and seyn mugwort.” “Mugworte, arthemisia, i. mater herbarum.” Cath. ang. Ang.-Sax. muʓwyrt, artemisia. Of the superstitious custom of seeking under the root of this plant for a coal, to serve as a talisman against many disasters, see Brand's Pop. Antiqu.

page 348 note 1 The correct reading is here given, probably, by the other MSS. The term mull is still retained in the Eastern counties, and in the North, and signifies, according to Forby, soft breaking soil. “Molle, pulver, et cetera ubi powder.” Cath. ang. Compare Low-Germ, and Dutch, mul, Ang.-Sax. myl, pulvis. “Mullock, or mollock, vide dust, or dung.” Gouldm. Chaucer uses the word “mullok,” Cant. T. v. 3871, 16,408. See the North Country Glossaries.

page 348 note 2 “To mulbrede, interere, micare. To make molle, pulverizare.” Cath. ang. Hence, perhaps, as it has been suggested in the note on Moldale, p. 341, to mull ale or wine, to infuse powdered condiments therein.

page 348 note 3 Pultina, Ms. The term Mulreyne may have been not inappropriately used to denote a mizzling shower, falling like fine powder, or mull; unless it may be preferred to seek a derivation from the French mouiller.

page 348 note 4 In the Inventory of Sir John Fastolf's effects at Caistor, 1459, is the entry “Larderia: Item, viij. lynges. Item, iiij. mulwellfyche. Item, j. barelle dim' alec' alb'.” Archæol. xxi. 278. Dr. Will. Turner, in his letter to Gesner on British fish, prefixed to the second ed. of Gesner, lib. iv. states that the fish called keling in the North, and cod in the South, on the Western coasts is termed melwel. Spelman states that the mulvellus of the Northern seas is the green fish, called in the Book of Customs at Lynn Regis melvel, and haddock, and in Lancashire milwyn. In the statute for the regulation of prices of fish and poultry, as given in Strype's Stowe, mulvel is mentioned. “Morue, the cod, or green fish, a lesse and dull-eyed kind whereof is called by some the morhwell.” Cotg. Merlangus virens, Cuv.

page 348 note 5 Mummynge seems to have denoted originally a dumb show, a pantomime, performed by masked actors, a Christmas diversion, regarding which many particulars will be found in Brand's Pop. Antiq. “Mummar, mommevr. I mumme in a mummynge. Let vs go mumme (mummer) to nyght in womens apparayle.” Palsg. Compare Dutch mumme, Germ, momme, larva; Fr. “momrne; mascarade, déguisement.” Roquef. “Mommon, a troop of mummers; also, a visard, or mask; also, a set, by a mummer, at dice.” Cotg.

page 348 note 6 This name for a dwarf does not appear to be retained in any of the local dialects, although preserved, as it would appear, in the surname Murchison.

page 349 note 1 “A muskett, capus.” Cath. ang. “Musket, a lytell hauke, mouchet.” Palsg. “Mouchet, espece d'oiseau de proye, c'est le tiercelet de l'espervier.” Nicot. The most ancient names of fire-arms and artillery being derived either from monsters, as dragons or serpents, or from birds of prey, in allusion to velocity of movement, this little hawk supplied the appellation musket; as also at a much earlier period it had furnished a name for the missile termed muschetta, or mouchette, in the XIIIth cent.

page 349 note 2 “Must, carenum, mustum.” Cath. ang. “Mustacium, i. mustum vinum, vel potus (qui) ex musto fit, et aliis potionibus.” Ortus. Mulsa, or mulsus, according to the Catholicon, was a drink compounded of wine, or water, and honey, commonly called meed; occasionally the term denotes new wine, which is the usual signification of must, as in the Wicliffite version, Dedis ii. 13; Cov. Myst. p. 382. “Must, newe wyne, movst.” Palsg. In Ælfric's Glossary, Julius, A. II. f. 127, are given “cervisa, vel celea, eale; medo, meodu; ydromellum, vel mulsum, beor.” Horman says, “We shall drynke methe, or metheglin; mulsum vel hydromel, non medonem.” According to the account given of Apomel, in Arund. MS. 42, f. 32, vº, mulsa, or mellicratium, is formed of eight parts water, and one of honey, boiled together; “idromellum, as oþer facultes vsen it; it is a lycur þat we callen wort, and it is seyd of ydor, water, and of hony, no“t þat hony goþ þer to, for hony towcheþ it but for it is swete as hony. It is water of malt, mulsum.”

page 349 note 3 Previously to the existence of a standing stipendiary force, provision was made for the defence of the realm, in any sudden emergency, by the law that every householder should have in his dwelling a warlike equipment suitable to his means and station, and should at certain fixed seasons present himself before the constables, or appointed officers, with his accoutrements, for inspection. This was termed the monstre, monstrum, or armilustrium, in N. Britain the “weapon-schawynge,” often mentioned in the Scotch acts, and in later times in England, the muster. The most curious and ancient ordinance to this effect is that passed at Winchester, 1285, 13 Edw. I. Stat. of Realm, i. 97; but the existence of a similar scrutiny at an earlier period appears by the documents printed by Wats, M. Paris, Auctarium, addit. p. 230. Spelman cites Rot. Parl. 5 Hen. IV. regarding the monstrum or monstratio of men-at-arms; see also the ordinance of Hen. V. in his statutes in time of war, “de monstris publicis, seu ostencionibus.” Upton. Mil. Off. 136. “Muster of men, bellicrepa.” Cath. ang. Palsgrave gives the verbs “I muster, as men do yt shall go to a felde, ie me monstre. I muster, I take the muster of men, as a capytayne doth, ie fais les monstres. What place will you sygne to muster your folkes in. Mustre of harnest men, monstre.”

page 350 notes 1 Siginarium, Ms. The distinction between Mv of hawkys, p. 347, and a mew for fatting poultry, deserves notice. Chaucer uses the word in the latter sense, Cant. T. 351.

page 350 note 2 This instrument of martial music appears to have been a sort of drum, of Oriental origin, and introduced into Europe by the Crusaders. Joinville speaks of the minstrels of the Soudan, “qui avoient cors Sarrazinnois, et tabours, et nacaires;” the term being evidently identical with the naqârah, or drum of the Arabs and Moors. See Ducange, v. Nacara, Roquefort, and Wachter. Menage, and other writers, supposed the nacaire to be a kind of wind-instrument, but the observations of Ducange on Joinville, p. 59, and the remarks of Daniel, Milice Franc, i. p. 536, prove beyond question that it was a drum. Cotgrave, however, gives “Naquaire, a lowd instrument of musicke, somewhat resembling a hoboy.” Nakerys are mentioned in Gawayn and the Grene Kny“ht, v. 118, 1016; and Chaucer's Knight's T. v. 2513. Froissart relates that Hugh Despenser the younger, being taken by the Queen's army in 1326, was led about “après le route de la Royne, par toutes les villes ou ils passoyent, à trompes et nacaires.” Vol. i. c. xiii. Amongst the minstrels in the household of Edw. III. 1344, is named “makerers, j. ” which may be erroneously written for nakerer, but in the Gesta Ludov. VII. c. 8, it is said “tympanis et macariis, et aliis similibus instrumentis resonabant.” See Household Ordin. p. 4, Harl. MS. 782, p. 63. Sir John Maundevile relates that near the River Phison is the Vale perilous, in which “heren men often tyme grete tempestes—and gret noyse, as it were sown of tabours, and of nakeres, and trompes, as thoughe it were a gret feste.” Voiage, p. 340. Trevisa, in his version of Barthol. de Propr. lib. xix. c. 141, says that “Armonia Rithmica is a sownynge melody—and diuers instrumentes serue to this maner armony, as tabour, and timbre, harpe, and sawtry, and nakyres.” Palsgrave gives “nauquayre, a kynde of instrument, naquair.” The precise period when the use of drums as martial music was adopted by the English is uncertain; R. Glouc. p. 396, alludes to their Saracenic origin, and describes the terror caused thereby, so that the horses of the Christians were “al astoned.” Nakers were used at the battle of Halidown-Hill, 1332, as appears by the “Romance,” or ballad on that victory, Harl. MS. 4690, f. 80; they are termed tabers in the prose account of the same, f. 79, vº. Minot says, in his poem on the alliance of Edw. III. with the Duke of Brabant, and other foreign powers, 1336, and their preparations for war with Philip de Valois,

“The princes, that war riche on raw,

Gert nakers strike, and trumpes blaw.”

The Nacorne, or nacaire, was probably the small kettle-drum, used in pairs, as seen in the figures given by Strutt, Horda, vol. i. pi. vi. from the Liber Regalis, written during the reign of Rich. II. The most curious representation is that etched by Carter, in his Ancient Sculpture and Painting, from a carved miserere, of the close of the XlVth cent, formerly in one of the stalls at Worcester Cathedral, and now placed on the cornice of the modern organ-screen, over the entrance from the nave.

page 351 note 1 “To nakyne, nudare, detegere, exuere. A nakynynge, nudacio.” Cath. ang. “Nudo, i. expoliare, &c.. to naken. Denudacio, a nakenynge.” Ortus. In R. Brunne's version of Langtoft's Chron. a satirical ballad is given on the victory of Edw. I. over the Scots at Dunbar, 1294. Ed. Hearne, p. 277.

“Oure fote folk put þam in þe polk, and nakned þer nages.”

Compare the extract from the original Chron. given by Mr. Wright, App. to Polit. Songs, p. 295. In Roy. MS. 20 A. XI. the word is written “nakid;” in Cott. MS. Julius, A. v. “nackened.” In the earlier Wicliffite version Levit. xx. 19 is thus rendered : “The filþheed of thi moder sister, and thi fader sister thow shalt not discouer ; who that doth this, the shenship of his flesh he shal nakyn.” A.-Sax. benacan, nudare.

page 351 note 2 “I nawpe one in ye necke, I stryke one in ye necke, ie accollette, and ie frappe au col. Beware of hym, he wyll nawpe boyes in ye necke, as men do conyes.” Palsg. “A nawp, a blow. Hit him a nawpe. See Yorksh. Dial. p. 68.” Bp. Kennett's Gloss. Coll. Lansd. MS. 1033. Compare Brockett, and Craven Gl. v. Naup.

page 351 note 3 “A natte, storium, storiolum. A natte maker, storiator. To make nattes, storiare.” Cath. ang. “Storiolo, to cover with nattes.” Ortus. “Nat maker, natier.” Palsg. In the curious poem entitled the Pilgrimage to Jerusalem, Cott. MS. Vitell. C. xIII. f. 172, vº, one of the characters introduced is the “Natte makere,” who holds long discourse with the Pilgrim. Nattes are mentioned again under the word Nedyl, as “boystows ware,” or coarse manufacture.

page 351 note 4 This word is usually written haterelle, but the letter n. taken from the preceding article, is here, as in many other like cases, by prosthesis prefixed to the substantive. “Occipicium, þe haterelle of þe hede. Imeon, dicitur cervix, a haterel.” Med. In the Lat.-Eng. Vocabulary, Roy. MS. 17 C. XVII. are given “Occiput, nodyll: vertex, haterele: discrimen, schade : tupa, fortoppe.” “An haterelle, cervix, cervicula, vertex.” Cath. ang. “Hatteroll, hascerel,” Palsg. Cotgrave says that a man's throat, or neck, is termed by the Walloons hastereau; but hasterel, or haterel, is an old French word of frequent occurrence, which signifies, according to Roquefort, the nuque, or nape of the neck. Hence, probably, may be derived the name of the Hatterel Hills, between Brecon and Hereford.

page 352 note 1 “Meditullium, a carte nathe (al. navelle.)” Med. “Modiolus, lignum grosmm in media rote, per quod caput axis immittitur, &c. Anglice nathe.” Ortus. “Naue of a whele, moyevl. Nathe, stocke of a whele.” Palsg. Ang.-Sax. nafa, modiolus.

page 352 note 2 “A nebbe, rostrum, rostrillum.” Cath. ang. “Neble of a womans pappe, bout de la mamelle.” Palsg. Ang.-Sax. neb, caput.

page 352 note 3 —boystors, Ms. Compare Boystows, rudis, p. 42, and Stoor, or hard, or boystows, hereafter. Broccus, or broca, in French broche, is a packing needle, an awl, or a goad. See Blount's Tenures, under Havering, Essex.

page 352 note 4 See Noyynge, or noyze, and Tene. Compare French noise, ennui; Lat. noxia.

page 352 note 5 Junius derives nick-name from nom de nique, an expression borrowed, as he supposes, from the Ital. niquo, iniquoi but there can be little doubt that the word is formed simply by prosthesis, the final n. being transferred from the article to the substantive. “Agnomen, an ekename, or a surename.” Med. “An ekname, agnomen, dicitur a specie, vel accione, agnominacio.” Cath. ang. “Nyckename, brocquart.” Palsg. “Sobriquet, a surname; also, a nickname, or by-word.” Cotg. “Susurro, a priuye whisperer, or secret carrytale that slaundereth, backebiteth, and nicketh ones name.” Junius, Nomenclator, by John Higins, 1585.

page 353 note 1 Compare Wyylnepe, cucurbita. Ang.-Sax. næpe, napus.

page 353 note 2 Nepeta cataria, Linn, common cat-mint, or nep. Ang.-Sax. næpte, nepeta. “Filtrum, quedam herba venifera, neppe.” Ortus. “Neppe, an herbe, herbe du chat.” Palsg. Forby gives the Norfolk simile “as white as nep,” in allusion to the white down which covers this herb.

page 353 note 3 “Ren, the nere.” Med. “Lumbus, a leynde, vel idem quod ren, Anglicè a nayre.” Ortus. “Neare of a beest, roignon.” Palsg. Gautier de Bibelesworth says, Arund. MS. 220,

“De dens le cors en checun homme

Est troué quer, foye, e pomoun (liuere ant lunge)

Let,plen, boueles, et reinoun (neres).”

In Sir Thomas Phillipps' MS. “reynoun, kydeneyre.” In the later Wicliffite version Levit. iii. 33 is thus rendered: “þei schul offre twey kideneiren (duos renes, Vulg.) wiþe fatnesse by whic þe guttis clepid ylion ben hilid.” The following recipe is given in Harl. MS. 279, f. 8 : “To make bowres (browes ?)—take pypis, hertys, nerys, an rybbys of the swyne, an chop them—an serue it forthe for a good potage.” In Norfolk, according to Forby, near signifies the fat only of the kidneys, pronounced in Suffolk nyre. Pegge gives the term as denoting the kidneys themselves. Compare Dan. nyre, the kidneys.