Introduction

Engagement in health research is increasingly being performed globally. Research institutions, international research ethics guidelines, and funding bodies now promote, or even mandate, engagement as an ethically and scientifically essential component of health research.Footnote 1 For example, grantees of the UK National Institute of Health Research’s Global Health Research programme are “expected” to involve patients and the public in the planning, implementation and evaluation of their research.Footnote 2

Yet many questions remain about the contribution of engagement to health research. A lack of consensus exists about what the ethical goals of engagement in health research should be and what approaches should be used to perform it. Many ethical goals, spanning the instrumental, intrinsic, and transformative, have been ascribed to engagement.Footnote 3 Engagement activities can be used for instrumental goals—to gain community “buy-in,” to increase study enrolment, or to ensure smooth research operations.Footnote 4 Engagement can secure intrinsic goals like showing respect or ensuring a sense of inclusion.Footnote 5 It also has “the potential to redress past harms; compensate for or resolve existing differences in power, privilege, and positionality; allow for marginalised voices and experiences to be represented in the production of scientific knowledge; and ensure that research is relevant and impactful.”Footnote 6 So far, no consensus exists on whether the ethical goals of engagement in health research should span the intrinsic, instrumental, and transformative in all studies or on whether the same ethical goals should apply in different types of health research (e.g., genomics, clinical, health systems).Footnote 7

Several types of engagement are used in health research projects: community control, partnership, consulting, and informing. Richard R. Sharp and Morris W. Foster describe a spectrum of power sharing in health research, from community dialogue through community consultation and approval to full partnership, where the latter implies the greatest community empowerment.Footnote 8 Community-based participatory research and other participatory research approaches are often utilized in public health research. They advocate for equal partnerships between researchers and communities by ensuring equitable contributions, recognition of community expertise, shared decisionmaking, and subsequent community ownership of research findings.Footnote 9 It has been argued that engagement as partnership should be employed in public health research,Footnote 10 but whether this should (always) occur in that and in other types of health research remains a matter of debate. Participatory approaches in biomedical and genomics research are not regular practice.Footnote 11 In community-controlled research, decisionmaking is shared but under the guidance of community partners or it is driven by community organizations with consultative input from researchers.Footnote 12

Numerous terms are used to describe engagement—involvement, participation—and those who are engaged—consumers, patients, service users, lay people, citizens, the public, and communities. These terms influence what individuals are perceived to be able to contribute, to know, and to be entitled to decide and, thus, fundamentally affect whether what those engaged say is heard.Footnote 13 Unsurprisingly, given the lack of consensus around ethical goals, approaches, and terms, high amounts of variability exist in how engagement is defined, designed, and applied in collaborative health research.

This paper addresses the following key questions: what should the ethical goals of engagement in health research be and how should engagement be performed? These questions remain the focus of significant debate in the ethics field and need to be informed by those being engaged. Very little literature exists that documents the voices and perspectives of people with lived experience and members of the public to inform ongoing debates.Footnote 14 In this paper, the terms “people with lived experience” and “members of the public” are primarily used. Their use reflects two key perspectives that people who are engaged bring to research studies: (1) the lay/public/citizen perspective and (2) the patient/community/service user perspective. The former refers to individuals who do not use the services or have the condition being researched. The latter refers to individuals who use the particular service being studied, have the condition being researched, or are from the community under study. In other words, they have lived experience of health systems, an illness, or community membership.

Why are such perspectives essential to document and use to inform ethical debates and guidance on engagement in health research? First, the most robust ethical guidance is informed by both theory and practice—in this case, the perspectives of those with key insights and experience of engagement in health research. This means not only researchers but also people with lived experience, engagement managers, and members of the public. If the latter voices are not captured, they are largely absent from ethics discourse and a key source of information is excluded or missing. Second, talking with them about engagement in health research addresses epistemic injustice and helps democratise knowledge within the ethics field.

As part of a qualitative study on sharing power in health research, the views of people with lived experience, members of the public, and engagement managers were captured on the following matters: what the value of engagement in research is, what ideal and tokenistic engagement look like, what terms they prefer to describe themselves, and the spectrum of their roles in research. The paper presents that data and then considers what insights it offers for what engagement should look like—its ethical goals and approach—according to those being engaged. In interviews, participants were asked about health research generally. It is beyond the paper’s scope to consider whether the identified ethical goals should apply to engagement in all types of health research or vary by field, or whether the ideal engagement approach proposed by interviewees applies generally or should be specified for different types of studies, but the value of exploring such questions in the future is recognized.

Methods

In-depth interviews were chosen as the primary method in this study because they allow for the rich details of key informants’ experiences and perspectives to be gathered. 22 semi-structured interviews were conducted with key informants in two main categories:

-

1) People with lived experience and members of public who are or have been involved in health research (18).

-

2) Engagement practitioners or managers who work in health research (4).

Involved in research was defined as having a role setting research priorities, collecting and analyzing research data; initiating and helping to design research projects; and/or disseminating research findings. This may have included conducting interviews with study participants; going to meetings to discuss a research project’s topic and questions, design, and/or protocol; being on advisory groups or steering committees for particular projects; or delivering findings of a research project at conferences. Thus, individuals who had solely been involved in research as participants were not interviewed for this study.

Sampling was initially purposive; potential participants with lived experience who had been involved in health research were identified in the UK and Australia through BP’s existing networks. In Australia, snowball sampling and posting information about the study on the Research4MeFootnote 15 Facebook group were then used to identify additional interviewees. In the UK, information about the study was sent out on a university’s patient and public involvement email listserv and this generated the remainder of interviewees. In total, seven interviewees were recruited through networks and fifteen were recruited through snowball sampling.

Participants were from Australia and the UK because engagement in health research is prominent in both countries, though it is more established in the UK. It was thought that participants from these countries would thus have ideas and experiences related to engagement in health research and that UK interviewees might potentially have different ideas and experiences relative to Australian interviewees that would be important to describe.

In total, five men and seventeen women were interviewed. Twelve interviewees live in the UK and ten in Australia. Interviews with Australian participants were carried out from March to August 2018. Interviews with UK participants were carried out from October to December 2018. Interviewees had lived experience of several chronic illnesses as well as several forms of disability (cognitive, psychosocial, and physical). They had been involved in a range of types of health research: biomedical, clinical, public health, health services, mental health, and disability research. Interviews continued until data saturation was achieved.

During interview, individuals were first asked what roles they had taken up in health research and what terms they had heard used to describe those engaged. They were then asked about their perspectives and experiences sharing power in health research projects in the context of those roles. For example, interviewees were asked: What is necessary for people like yourself to meaningfully participate in health research? When people like you are involved in health research, what is important to sharing power over a given project with them?

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and thematic analysis was undertaken by two coders in the following five phases: initial coding framework creation, coding, inter-coder reliability and agreement assessment, coding framework modification, and final coding of entire dataset.Footnote 16

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the University of Melbourne Human Ethics Advisory Group.

Results

Five themes identified were: the value of engagement in health research, ideal engagement, tokenistic engagement, the language of engagement, and roles. Each is discussed below.

Value of Engagement in Health Research

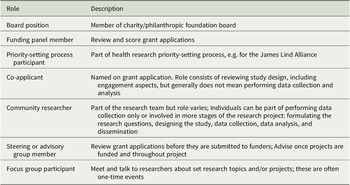

Nine main benefits of engaging people with lived experience and members of the public in health research were identified by interviewees (Table 1). The first five benefits in Table 1 describe the value of engagement for health research; the latter four describe the value of engagement for those engaged. Only UK participants identified “enhancing health research priority-setting and funding allocation” as a benefit. This likely reflects the fact that three-quarters of UK participants had roles on funding panels for health research, which was not a common role for Australian interviewees to have.

Table 1. Value of Engaging People with Lived Experience and Members of the Public in Health Research

Ideal Engagement

Interviewees affirmed that it was important to engage with the diversity of a society or community, especially those who are hard to reach and different to research team members. They called for:

Trying to get people in who are as wide a cross section of everyone who you might research that you can, especially people not like you whether that’s people of colour, people who have minorities, sexualities, people who are disabled, people who don’t speak English, whatever. But the people that are gonna think of the things that you don’t think of, which is mostly the people that are least like you, and unfortunately that often means it’s the people that are hardest to research, or hardest to pull in as co-designers.

It was ideal to start engagement from priority-setting and resource allocation by funders, especially when deciding what research gets done with public money:

Quite a few charities and so on that certainly started down that route where they did the PPI [patient and public involvement] bit almost first of all just to find out what the crucial topics were amongst the patients and public, then they went back and said right which of these can we make into a really good research topic.

Within individual research projects, it was ideal to begin engagement at the planning and brainstorming phase prior to putting in grant applications. People with lived experience and members of the public should be responsible for or be part of setting research topics and questions, rather than coming on board to research projects that already have key parameters determined.

Involving people with live experience and members of the public was also recommended to occur in all stages of research projects by several interviewees. However, an engagement manager felt that it was ideal to only involve them in stages where they could make a difference and where their expertise was relevant.

Interviewees discussed it being ideal to involve people with lived experience and members of the public as decisionmakers: “We’re all gonna make a decision and your vote and your say is equal to some, the person who works in a senior position.” An interviewee further suggested it would be ideal if “community researchers” were able to lead and direct health research projects.

Engagement should occur in local spaces that are convenient for people with lived experience and members of the public to get to and that they feel comfortable in, rather than at universities, hospitals, or locations at quite a distance from where they live. No differences were observed between the UK and Australian interviewees’ perspectives on ideal engagement.

Tokenistic Engagement

Two core and related dimensions of tokenistic engagement were described by interviewees: feeling like engagement was a tick box exercise and feeling used. A tick box exercise could occur when those engaged are purposefully selected because they are known very well to the research team and will agree with everything they say. It could also occur where people with lived experience and members of the public’s level of participation is informing or certain types of consulting. Consultations where people are invited to attend meetings but are not expected or encouraged to say anything is one type of tokenistic engagement. Those engaging them do not truly want to hear their opinions and ideas: “I was shy at first but I quickly discovered I was a token… they’d be quite happy if I sat there with my mouth shut the whole time.” Consultations that occur after most or all parameters of the research project are set so that those engaged can endorse decisions that have already been made by others is another type of tokenistic engagement. In such consultations, input from people with lived experience and members of the public is disregarded, unless it agrees with what has already been decided, and/or very few changes are made based on it.

Thus, tick box exercises generally mean that people with lived experience and members of the public are excluded from decisionmaking. Others decide which parts of the research project they’ll be part of, who is consulted, and whose input is used:

All the power is, all exactly on one hundred percent on one end of the equation. It’s not participatory in the sense that we usually use the word in English. It’s more accurately described as consulting.

Tokenistic engagement makes those engaged feel used. This can happen when it is a tick box exercise. It can also occur when people with lived experience and members of the public feel like they have been engaged primarily to enhance the credibility or fundability of a particular research project. For example, when their involvement is about the “cultural cache of getting right group on board.” No differences were observed between the UK and Australian interviewees’ perspectives on tokenistic engagement.

Language of Engagement

Many terms were used by interviewees to refer to who was being engaged in health research, including:

-

• Consumer advocate

-

• Expert consumer

-

• Patient partner/expert

-

• Lay advisor

-

• Public contributor

-

• Patient representative

-

• Interested member of the public

-

• Citizen scientist

-

• Community researcher

-

• Disability researcher

Preferred terms varied by interviewee and included: patient partner, consumer/patient advocate, expert patient, community researcher, public contributor, lay representative, lay advisor, citizen scientist, and expert patient. Nonpreferred terms were patient, consumer, and community researcher:

I think consumers belong at Woolworths [supermarket chain].

The term co-researcher establishes a hierarchy between what is a university researcher and what is a co-researcher with lived experience. To me this kind of language does not speak to us being colleagues and being seen in an equal light. It does not level out the playing field. In fact, I find because this language is not neutral it highlights that we are yet to be seen as competent to navigate a university structure, much like our fellow academic staff and researchers.

Although the terms used varied considerably, their definitions had the following four dimensions: perspective, representation, purpose, and background. The terms described individuals as bringing one of two types of perspectives to health research—namely, the lay/public/citizen perspective or the patient/service user/community perspective. Depending on their perspective, those engaged represent their community, the public, or patients that receive a particular service or have a particular condition and advise other members of the research team from that perspective. Their purpose is to advise from a perspective that is not academic or clinical (researcher or doctor) on research projects’ design and the implications of proposed and funded research projects for the patient, family and wider community. In terms of their background, the terms referred to individuals who are external to universities and research institutions. They can either have a science or medical background or have no science or medical background. They can be either new to engagement or an expert, with a lot of engagement experience in health research.

Engagement Roles

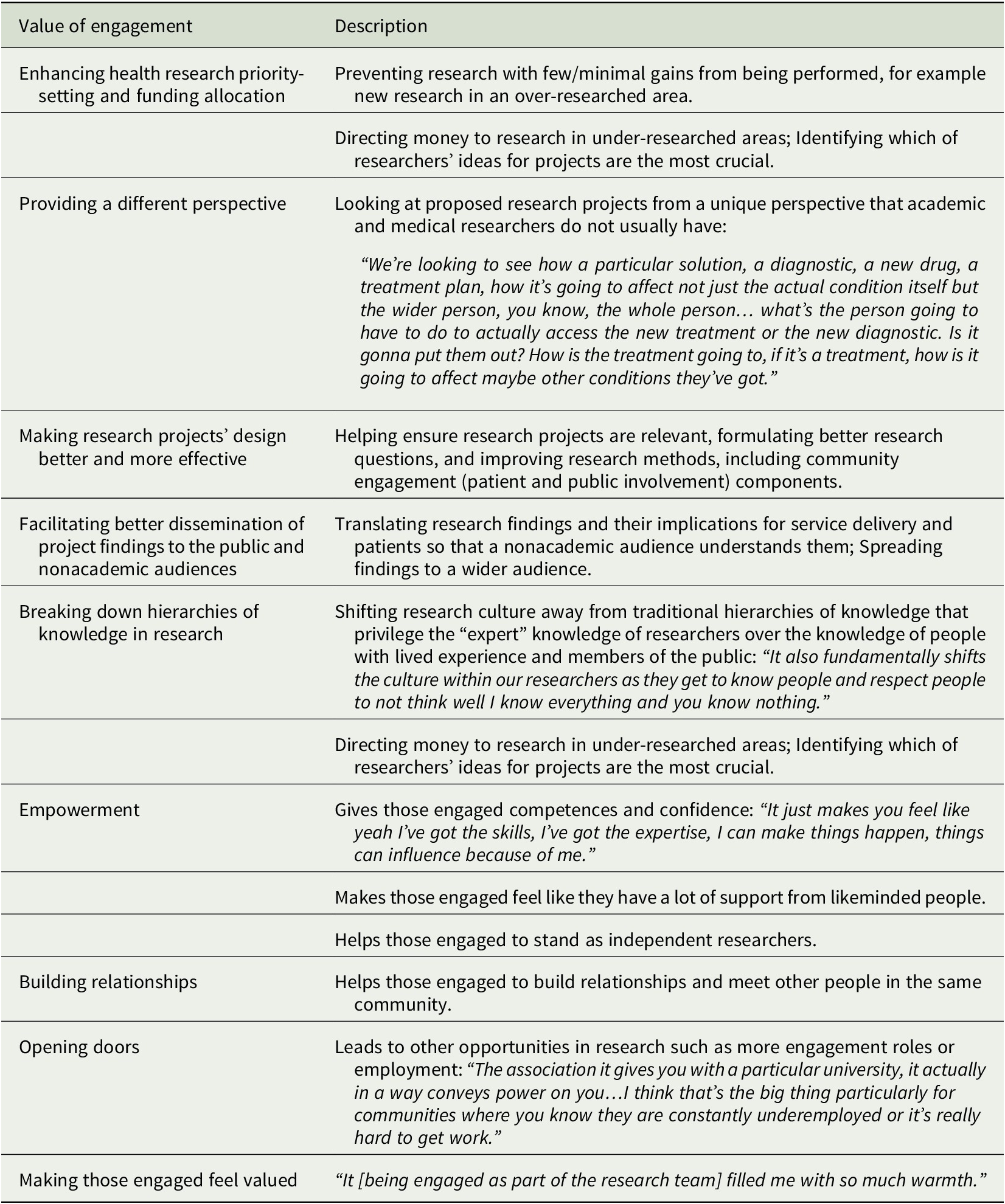

Several types of roles for people with lived experience and members of the public who are engaged in health research were described (Table 2). Roles on funding panels, priority-setting processes, and university committees that review projects pregrant submission were not mentioned by Australian interviewees. The community researcher role may be less common in the UK.

Table 2. Interviewees’ Roles in Health Research

A hierarchy or pyramid of different engagement roles was described by an interviewee from the UK. Board member positions were at the top, followed by being on funding panels, next being a co-applicant, a co-researcher, and then being on research advisory groups or steering committees. Being part of focus groups was at the bottom of the pyramid.

Discussion

This section discusses what insights study findings offer for what engagement should look like—its ethical goals and approach—according to those being engaged. The value of engagement described by interviewees (Table 1) speaks to engagement potentially serving instrumental, intrinsic, and transformative ethical goals, most of which have been identified in existing ethics literature.Footnote 17 Notably, however, enhanced health research priority-setting and resource allocation by funders is an instrumental value of engagement identified by interviewees that is not typically attributed to engagement in the ethics (or community-based participatory research) literature. This goal was identified by the UK interviewees, who, in contrast to Australian interviewees, had experience being on funding panels.

Empowerment is a transformative goal identified by interviewees that is less commonly identified in the ethics literature, but it has been proposed as an important goal if engagement is to challenge unequal power dynamics between researchers and those engaged.Footnote 18 More often, strengthening skills or capabilities for participants or communities has been identified as an ethical goal for engagement,Footnote 19 but skill-building in itself comprises only one aspect of empowerment. Future research could explore in more depth how those engaged in health research are or would like to be empowered to develop a better understanding of what empowerment should mean in the engagement context.

Making research projects’ design better and facilitating better dissemination are consistent with instrumental ethical goals such as improving the ethical and scientific quality of research, ensuring the relevance of research, and increasing the likelihood of research having a long-term impact. Providing a different perspective and breaking down hierarchies of knowledge in research are consistent with the transformative ethical goal of democratising knowledge.Footnote 20 Building relationships and feeling valued are consistent with intrinsic goals for engagement.

The value of engagement described by interviewees in this study also largely aligns with the value ascribed to participatory research approaches. Cargo and Mercer (2008) identify such approaches’ value as making studies more relevant to local needs and concerns; generating local ownership, empowerment, and capacity building through active participation; and enhancing dissemination by better reaching diverse audiences.Footnote 21 Wallerstein and Duran (2010) further speak to community-based participatory research’s capacity to help break down hierarchies of knowledge. They note that

[t]he challenge of evidence is difficult to overcome, as researchers are often perceived as experts with the power of empirically tested scientific knowledge. CBPR has championed the integration of culturally based evidence, practice-based evidence, and indigenous research methodologies, which support community knowledge based on local explanatory models, healing practices, and programs. Footnote 22

The ideal approach to engagement described by interviewees would advance many if not all of the aforementioned ethical goals, including transformative ones. Yet the proposed approach differs from what often occurs health research practice in several ways. First, interviewees affirmed the importance of engaging the diversity of a society or community, including the hard to reach. Lauren Ellis and Nancy Kass (2017) found that Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute investigators in the United States usually engaged patients who they already knew or identified patients by referral from those in their professional network. It was rare for the investigators to report using systematic recruitment processes with sociodemographic diversity as a goal.Footnote 23 In global health research, although most individuals recruited for engagement activities are part of the research population or host community, they are not necessarily members of disadvantaged groups within it.Footnote 24

Second, interviewees felt that engagement should start early in the research process: during priority-setting and resource allocation by funders and prior to grant submission for individual projects. In practice, most engagement activities take place after grants are awarded.Footnote 25 Third, interviewees called for being engaged as decisionmakers, rather than as consultants who provide input or simply being informed. In global health research, engagement seems to focus more on promoting consultation.Footnote 26 In Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute projects, some researchers engaged patients to provide reactions and advice, whereas others described situations where patients were more equal decisionmakers.Footnote 27

Interviewees’ description of ideal engagement does, however, align with core features of community-based participatory research and other participatory research approaches. Such approaches call for diverse perspectives (i.e., all segments of the community potentially affected by the research) being represented and that participation occur in all phases of research projects, including when setting the research topic and questions.Footnote 28 At the same time, community-based participatory research has other principles that interviewees did not mention (e.g., action, long term relationships). Additionally, community-based participatory research primarily focuses on the project level, whereas interviewees’ recommendations were that ideal engagement includes but goes beyond that level to comprise roles for people with lived experience and members of the public in research governance and at institutional, funding, and national levels. For example, they believe ideal engagement encompasses involvement in priority-setting and resource allocation at the funding level. Future research can further explore what such roles should look like.

Of the engagement roles described by interviewees, being funding panel members, priority-setting process participants, co-applicants, and community researchers seem potentially more likely to achieve ideal engagement. Other roles like being part of an advisory or focus group would still be useful; they are often key to building the experience needed to take on roles higher in the hierarchy and can still advance certain ethical goals of engagement. However, if the majority of roles for people with lived experience and members of the public are being advisory or focus group members, this seems inconsistent with the type of engagement that interviewees wanted to occur. A shift is therefore likely needed in many countries. In Australia, for example, engagement roles on funding panels are rare.

This study also provides more information on what tokenistic engagement and, in particular, features of “tick box exercises” look like from the perspective of people with lived experience and members of the public. Ideal engagement was, of course, preferable to interviewees, but, at a minimum, engagement approaches should avoid having features of tick box exercises and making those engaged feel used.

Although the paper speaks to ethical goals and ideal approaches to engagement in health research, it is not yet clear that the same ethical goals and approaches should apply in all types of health research. It is possible that different goals and/or approaches should be used in different types of health research. What engagement should look like for engagement in genomics research studies may look somewhat different to what it should look like for engagement in public health research studies. Future research should seek to capture the views of people with lived experience and members of the public on these matters.

Finally, this study demonstrates that a plethora of terms continue to be used to describe those engaged in health research. Preferred terms varied considerably amongst interviewees, suggesting that it is perhaps best to ask those engaged as individuals or as a group (when several people are engaged together) what term they would like to be called. Future research could usefully explore how the various terms restrict or expand what those engaged are perceived to be able to contribute, to know, and be entitled to decide in health research.

There were no differences between the UK and Australian interviewees’ responses in regards to ideal and tokenistic engagement. UK interviewees identified an additional value offered by engagement in health research. They also described additional engagement roles for people with lived experience and members of the public based on their experience on funding panels and as part of James Lind Alliance priority-setting processes.

There were several limitations to this study. Interviewees were recruited from Australia and the UK only. Although engagement in health research is increasingly common in both these countries, there are other countries where engagement is frequently occurring, including in low and middle-income countries. Future research should seek to access their insights and experiences.

The interviewee sample had fewer men than women, members of the public than people with lived experience, and individuals living in urban than rural areas. The diversity of interviewees is also somewhat unclear, as the study did not collect demographic data about interviewees. UK interviewees self-selected themselves to participate after information about the study was sent out on a university’s patient and public involvement listserv. That listserv in itself was not thought to be exceptionally diverse by the engagement practitioner who runs it. Lack of diversity was identified as a problem for engagement in health research as a whole by interviewees. Nonetheless, interviewees had lived experience of a range of disabilities (cognitive, psychosocial, and physical) and chronic illnesses. Several mentioned being of non-Caucasian ethnicities such as African, Hungarian, and Indigenous. In terms of age, Australian interviewees spanned younger ages (20s and 30s) to retirement age. UK interviewees were generally older but not all were retired.

Conclusions

This study describes the views of people with lived experience, members of the public, and engagement managers from Australia and the UK on engagement and sharing power in health research. Their insights suggest several ethical goals, spanning the instrumental, intrinsic, and transformative, are appropriate for engagement in research. Although goals related to priority-setting, allocating funding, and empowerment are not as commonly discussed in the ethics literature, this study indicates they may be valuable aims of engagement practice. It further suggests an ideal approach to undertaking engagement means engaging the diversity of a society or community, including the hard to reach, as decisionmakers from the start of the research process.

These goals and ideal engagement approach may be best advanced where those engaged have the roles of funding panel member, priority-setting process participant, co-applicant, and/or community researcher. A shift in engagement practice and the roles commonly available to people with lived experience and members of the public are likely needed in many countries to achieve the proposed engagement ideal, as such roles and practices are not yet common in most countries.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Natalia Evertsz and Jessica Snir for their assistance with coding of interview data.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by an Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (Award No. DE170100414). The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the views of the ARC.