In December 1922, the Teatro Alfieri in Turin scored a hit with Scugnizza. Composed by Mario Costa to a libretto by Carlo Lombardo, the new operetta was set in contemporary Naples and told the story of Salomè, a street urchin in love with the mandolin-playing Totò. A group of visiting Americans are enchanted by the Neapolitans, and wealthy widower Toby Gutter offers to marry Salomè (the titular scugnizza), precipitating a series of romantic crises that are eventually resolved. Scugnizza quickly did the rounds of the main Italian operetta venues, and the magazine L’opera comica was clear about the reasons for its success:

Finally we can record, in the most unconditional way, the true and enthusiastic success of this frankly Italian operetta [schiettamente italiana]. We are happy with this triumph, and all the more so to witness it today, when in general our record of musical genius is challenged by forms of exoticism that have such a hold on – and are so easily welcomed by – public taste. Here, instead, everything speaks to and exalts in the spirit of our beautiful country. From the story set against the background of the most beautiful sky in Italy, to the deliciously unbridled music, imaginative and full of nostalgia throughout its compelling workmanship.Footnote 1

This rhetoric of innate, unambiguous Italianness was far from new. Already in the 1870s sceptical Italian critics had remarked on the need for French operetta to be resisted with a resurgence of opera buffa – a discourse that ran in parallel with discussions about national operatic style throughout Liberal Italy (1861–1922).Footnote 2 Nor was it the first (or last) time that a work by Costa or his contemporaries was identified as the first authentically Italian operetta. This would become a trope through the 1910s and 1920s, as critics increasingly sought to identify a canon of native operettas to match the operatic one, and to place the genre’s history within a broader narrative of European operetta. At stake, fundamentally, was the question of what genuinely Italian operetta ought to sound like, and from which native traditions it should develop. In a country notoriously marked by regional differences and rivalries, the options were legion. Writing in Musica e scena in 1925, critic Cesarino Giardini argued that Italian operetta should ground itself nationally via various traditions – be it opera buffa, theatre, song or commedia dell’arte – to offer an entertainment that was openly comic, but still classifiable as art, unmistakeably reproducing the Italian national character.Footnote 3

If Scugnizza was hardly unique in being identified as ‘frankly Italian’, the particular terms of its critical success – its evocation of the Italian South, its Neapolitan music, its supposed rejection of exoticisms such as jazz – can nonetheless expose key issues surrounding this search for a native operetta. Costa (1858–1933) was credited in numerous early accounts as being a fundamental figure in the rise of Italian operetta, and even praised as the ‘father’ of the genre by some critics.Footnote 4 But as L’opera comica’s review reveals, truly Italian operetta was frequently perceived to be a very recent phenomenon. A closer look at Scugnizza complicates this picture further, because if the operetta makes abundant use of Neapolitan song and regional settings, it also mixes them with newer American dance forms in a way typical of Lombardo’s own operettas – self-consciously packaging Neapolitan music as a branch of the international entertainment sector. Costa himself had achieved local and national celebrity in the 1880s and several of his operettas would continue to be performed regularly throughout the first half of the twentieth century.Footnote 5 But his national reputation was founded on his success as a composer of Neapolitan songs and romanze, particularly in collaboration with the distinguished Neapolitan author Salvatore di Giacomo, as well as on his highly successful pantomime L’histoire d’un Pierrot (premiered at Paris’s Théâtre Déjazet in 1893, and written to an outline by Fernand Beissier). His early operettas Le disilluse (1889) and Capitan Fracassa (1909) were followed by a cluster after the First World War: Il re de chez Maxim (1919), Posillipo (1921), Scugnizza (1922), Il re delle api (1925) and Mimì Pompon (1925).

The Neapolitan connection here is key, I argue, in so far as it exposes the complex – but central – role Naples played in the development of an Italian operetta tradition, while setting up a fascinating historiographical counternarrative to familiar histories of Italian opera in this period. Carlotta Sorba and Elena Oliva have both pointed to the importance of Naples in the initial development of Italian operetta in the 1870s and 1880s, shaped as it was by the city’s intense theatrical scene as well as by the development of new entertainment venues such as the Salone Margherita and Teatro Eden in the 1890s.Footnote 6 As Oliva argues elsewhere in this special issue, Neapolitan song featured in several of the earliest Milanese and Roman dialect operettas during these decades, already imbuing canzone napoletana with an incipient and potent national status despite the local success of alternative dialect operetta traditions. Tellingly, many of the individuals who would emerge as the first truly national figures in Italian operetta from the 1880s onwards were professionally based in Naples or trained at the Naples Conservatory, underlining the city’s centrality to the Italian operetta industry. These composers were, in addition, central to the revival of Neapolitan song from the 1880s onwards – figures including Costa, Lombardo, Vincenzo Valente, Gaetano Scognamiglio, Eduardo di Capua, Ettore Bellini, actor and impresario Luigi Maresca, and even Francesco Paolo Tosti, whose songs were posthumously arranged into a ‘jukebox operetta’ by Ricordi in 1926 (under the title Ideale). These composers reveal a genealogy of Italian operetta in which its reported ‘Italianness’ did not derive from a straightforward revival of opera buffa – even within Naples – but rather from the development and adaptation of other Italian music-theatrical genres in tandem with foreign models: a mix that could make Italian operetta feel distinctly modern, while raising complex questions over operetta’s status as a genre.

This issue of genre is crucial, because it is Italian operetta’s generic ambiguity and capaciousness that may be most useful in reconfiguring our understanding of the Italian musical field more broadly in this period. As Matthew Gelbart has recently contended, genre is a basic ‘interface’ for constructing musical meaning, and it remained crucial as a method for classifying and marketing works in the rapidly expanding musical marketplace of the late nineteenth century.Footnote 7 Georgina Born has similarly stressed the intersecting social and aesthetic ‘planes’ that constitute musical genre: encompassing musicians, audiences, institutions and overlapping social identities that collectively make up a point of ‘contingent convergence’, and reflecting the highly social nature of musical generic constructions.Footnote 8 Italian – and particularly Neapolitan – operetta can offer a crucial new perspective on the social work of genre, shedding light on the overlapping hierarchies and conventions that shaped musical genres in Italy at this time. The exchange between operetta and Neapolitan song moreover exposes the foundational links between operetta and the popular music industry that would define the genre’s fortunes throughout the first decades of the twentieth century.

If Naples was the crucible in which the italianità of operetta was forged, then its casting also took place at a crucial moment. 1890 is usually credited as a crucial turning point in history of Italian opera, the premiere of Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana in Rome helping to usher in the Giovane Scuola and the verismo movement as a whole. Verismo, famously, engaged with depictions of the Italian South as part of its early effort to create realist drama, a move closely linked to the ‘Southern Question’ in post-unification Italy.Footnote 9 As historians have noted, depictions of the mezzogiorno had been a staple of Northern Italian publications since the mid-1870s, and regularly teetered between domestic orientalism and a more picturesque approach that framed the South as the primitive Italian heartlands.Footnote 10 Yet even Mascagni would spend much of the decade prior to Cavalleria rusticana closely involved with the operetta scene, working with both Maresca and Lombardo before focusing primarily on opera.Footnote 11 If the Giovane Scuola were overwhelmingly trained in Milan (and associated with a revival of Italian opera shaped by French and German importations), the emergence of Italian operetta can – to a significant extent – be seen as a Southern musical counterpart: one that demonstrates the persistence of an Italian comic tradition often engaging with local subject matter, while tightly bound up with theatrical practices from France, Austria and beyond.Footnote 12 Focusing on Neapolitan operetta can thus provincialise opera and reorientate familiar geographies of Italian music, while uncovering connections between operetta’s ambivalence and wider (local) discourses of the Italian South. The significant national trend for operettas engaging with Neapolitan song or Neapolitan subject matter by the 1910s and 1920s moreover suggests that the cultural imagination surrounding Naples in the post-unification era played a key role in shifting perceptions of Italian operetta across Italy, as composers and critics sought to define a position for a genre that was ambiguous in genealogy and cultural standing. Scugnizza would, in turn, become one of the very few Italian operettas that has continued to be revived periodically up to the present, its early reception as authentically Italian continuing to shape its limited profile today – even if the reality is considerably more complex.

In what follows, I first place the emergence of ‘Neapolitan’ operettas in the late 1800s in the context of the city’s diffuse and varied entertainment sector, considering the generic circulations key to Naples’s theatrical life and the influence of French practices. I then turn to the competing national models for Italian operetta by the early twentieth century, particularly as the arrival of Silver Age Viennese operetta prompted a further surge of operettistic activity and increasingly heated debates about the identity of the Italian variety. In the article’s final section, I return briefly to Scugnizza to consider how connections between Naples, Neapolitan song and operetta were self-consciously marketed by the early 1920s in ways that shed light on the centrality of Neapolitan song to conceptions of Italian operetta as a genre that straddled high and low, national and regional, past and present – even as Italian operetta itself failed ever to achieve a comparable level of global success as the songs that flowed through it. Costa can act as a guide to this vast and variegated terrain, allowing us to trace the circulations of song between salon and stage, Naples and Paris, as the dream of a truly Italian operetta was fleetingly realised and endlessly re-cast.

The city of theatres

Operetta arrived in Naples in a theatrical environment of extraordinary complexity and scale.Footnote 13 Two royal institutions – the Teatro San Carlo (opened 1737) and the Teatro del Fondo (1779) – existed alongside a vast variety of private theatres catering to different genres and audiences, with operetta flourishing across both socially elite and less exclusive venues. As Alessandro de Simone has argued, this reflected the Bourbon court’s support for a wide range of smaller venues and street theatres following its restoration in 1815 – including puppet shows, marionettes, carnivals and equestrian spectacle, as well as spoken theatre and music venues – thereby turning Naples into a ‘vast stage’ marked by ‘theatrical and para-theatrical’ entertainments that significantly shaped its international reputation.Footnote 14 The loss of political power following Italian unification in 1861 gave rise to financial pressures affecting the theatrical scene as a whole, and even prompted the closure of the San Carlo for three seasons during the 1870s. Yet the severe poverty that characterised areas of Naples – immortalised in Matilde Serao’s Il ventre di Napoli (1884), which followed the cholera epidemic that same year – also spurred on many of the same urban modernisation processes evident elsewhere on the peninsula, including the emergence of new entertainment venues.Footnote 15 Clustered in the central districts of the city around the Lungomare and Via Toledo, Naples’s numerous theatres catered for a range of audiences. Following the arrival of the Grégoire brothers in 1868, operetta was soon performed both in dedicated theatres (notably the Theatre Grégoire in Piazza Dante) and in Italian and Neapolitan translation in venues that had traditionally performed opera buffa. The Teatro Nuovo (founded in 1724 and rebuilt in 1861 following a fire, and long known for opera buffa) quickly became the main venue, overtaking the Teatro del Fondo (renamed the Teatro Mercadante in 1871). The latter, as well as being an operetta hub, also became the artistic centre of legendary Neapolitan comic actor and author Eduardo Scarpetta during his early career.Footnote 16 Operetta was also performed at other theatres of varying sizes and ages: among the largest were the Teatro Fenice (opened 1806), the Teatro Bellini (rebuilt following a fire in 1869 to a design inspired by Paris’s Opéra-Comique) and the Politeama (1871); smaller venues included the Teatro Partenope (1828), the Teatro Sannazzaro (1874), the Teatro Rossini (1870) and the Teatro Filarmonico (1870).Footnote 17

As Annamaria Sapienza has shown, Naples already had a significant tradition of operatic parody during the nineteenth century in both prose and music, ranging from comic depictions of Neapolitan theatre companies seeking to stage works such as Il trovatore, to transplantations of operatic plots to Neapolitan contexts.Footnote 18 These operatic parodies would play a key role in shaping a local operetta tradition, provoking operetta parodies of new works and inviting an absurdist element in new operettas. Indeed, while Sapienza has characterised this tradition as in decline by the 1870s – in response to a falling number of successful new Italian operas to burlesque – surviving theatrical records indicate both regular revivals of older parodies as well as the premieres of new works. Among the former, Luigi Fischetti’s Aida di Scafati (1873) was especially successful during the late nineteenth century, while Pasquale Altavilla’s prose parody Na famiglia ntusiamata pe la bella musica d’o Trovatore con Pulcinella finto Barone Tira-Tira (1860) would be revived throughout the 1890s by the Giuseppe de Martino company, featuring a quartet from Il trovatore with de Martino himself taking the part of Leonora (here ‘Eleonora (Pulcinella)’). New verismo works were also regularly parodied, from a range of responses to Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana (1890) to Scarpetta’s prose work La bohème, which included a burlesque in the fourth part (Scarpetta playing Mimì).Footnote 19 At the same time, foreign works were now open to similar treatment, with Lecocq’s La fille de Madame Angot a particularly frequent object of parodies, alongside burlesques of Bizet’s Carmen and Chueca and Valverde’s famed zarzuela La gran vía. While operettas by Offenbach had also been parodied elsewhere in Italy during the 1860s, the longstanding importance of the Teatro San Carlino (demolished in 1884) as a venue for comedy gave particular strength to this local tradition of mixed registers and comic juxtapositions.

Neapolitan composers also began writing original works in a Parisian vein during the 1870s, even if these works were usually still listed as opere buffe and could mix together elements of opera buffa, parody and operetta. As Elena Oliva has highlighted, despite critical anxieties prompted by the arrival of French operetta, local musicians were quick to engage with stylistic features of the new genre, an approach that was comparable to the openness to Meyerbeer and Wagner demonstrated in such cities as Bologna and Florence at the same time.Footnote 20 A French influence is immediately evident in works such as Francesco Palmieri’s Don Giovanni (Teatro Nuovo, 1884), which concluded with a Cancan, while prominent figures including Leopoldo Mugnone, Federico Ricci, Nicola de Giosa, Cesare Rossi and Emilio Usiglio all composed works that incorporated couplets or French dances. Mugnone’s Mamma Angot al Costantinopoli (1875) – already discussed by Sapienza – provides an especially powerful example of such fusion, mixing parody with new composition and a Neapolitan song influence in the final ensemble.Footnote 21 Meanwhile, works such as de Giosa’s Napoli di carnovale (1876) would also be quickly recognised across Italy as being directly influenced by French operetta, despite de Giosa having previously inveighed against the popularity of French operetta.Footnote 22 The operetta influence is particularly obvious in the third act, which unfolds at the Teatro San Carlo and features ‘Strofe popolari’ performed by Pulcinella accompanying himself on the tambourine.Footnote 23 A decade after his notorious declaration that operetta had killed opera buffa, Francesco D’Arcais concluded in 1888 that:

Ultimately, more than a protest against operetta, [Napoli di carnovale] was a healthy reaction to Neapolitan opera buffa, which from the sublime heights to which Cimarosa had brought it had descended to the musical obscenity [turpiloquio musicale] of Cicco e Cola … Napoli di Carnovale ennobled operetta and at the same time raised the prestige of the old opera buffa, of which, truth be told, the operetta is nothing but a derivation.Footnote 24

Already in the 1870s, then, what Jacques Derrida famously described as the ‘contamination’ inherent in all generic distinctions was being hastened as divides between opera buffa and operetta weakened and genealogies were reversed.Footnote 25

The regular revival of particularly successful Neapolitan opere buffe such as de Giosa’s Don Checco (1850) and Errico Petrella’s Le precauzioni (1851) further highlights the complexity of the early comic opera and operetta landscape, even if the term ‘opera buffa’ seemed to have fallen out of fashion by the 1880s.Footnote 26 Neapolitan opere buffe from the mid-nineteenth century continued to draw on commedia dell’arte elements, and made significant use of stock characters such as the fool, the thief and the upwardly mobile lower-class figure, with Pulcinella embodying many of the more devious traits.Footnote 27 The use of Neapolitan dialect – particularly for buffo characters – had long hampered the circulation of works to the North of Italy, and operettas such as Napoli di carnovale were regularly translated into Italian to enable national circulation. Even more significant in this context is the longstanding tendency of Neapolitan opera buffa to include spoken dialogue – a practice not used elsewhere in Italy due to a perceived aesthetic incongruity, but one that provided a strong parallel with operetta and allowed for extensive scenes of improvisation and comedy with only passing relation to the overall plot (such passages were transformed into recitative to enable circulation outside Naples). What is more, works such as Napoli di carnovale already included elements of popular song in a way that could connect them with operetta, the first number being a ‘canzone popolare’ sung by the chorus; Luigi Ricci had also incorporated a tarantella into La festa di Piedigrotta (1850), foregrounding the famed Neapolitan song festival founded in the 1830s.Footnote 28

Thus, if by the 1880s critics across Italy declared that the opera buffa tradition had been destroyed by the arrival of operetta, the Neapolitan situation reveals both the persistence of opera buffa and its hybridisation with newer genres that belies any clear distinction.Footnote 29 As Ruben Vernazza has argued, this period more broadly also witnessed an ‘operett-isation’ of earlier, short comic works such as Donizetti’s Il campanello (1836) – works that were either explicitly reclassified as operettas or paired with new works in a way that implied continuity.Footnote 30 Nicola d’Arienzo’s commedia lirica I due mariti (Teatro Bellini, 1866), for example, would be described as an ‘operetta’ by Il pungolo when it was revived at the Teatro Rossini in 1871, and individual acts of Italian works by Ricci or Mugnone or Donizetti (Don Pasquale) were regularly packaged together with Offenbach, Hervé or Auber.Footnote 31 At the same time, some conservative Neapolitan critics continued to dismiss operetta as a tedious, meretricious foreign import, with Napoli musicale (a leading periodical) declaring in June 1886 that operetta as a genre – represented here by foreign works – thankfully appeared to be on its way out.Footnote 32

The remediation of operetta and its interpenetration with local traditions emerges with especial clarity in the case of Scarpetta’s play Na santarella, premiered at the Teatro Sannazzaro in May 1889. Popular stage works were regularly adapted as operettas, and in this case Scarpetta’s play was itself an adaption of Hervé’s vaudeville-operetta Mam’zelle Nitouche (1883), translated by Scarpetta into Neapolitan and adapted significantly to place it within Neapolitan everyday life by adding several minor characters and transforming the main part into the role of Felice Sciosciammocca.Footnote 33 This comic figure was strongly associated with Scarpetta, and was drawn from the work of dialect author and parodist Antonio Petito (1822–76). In the play he combines a double career as a church organist and composer of operetta named Arturo Maletti. As he declares in the second scene, the public has an insatiable appetite for the genre even if they have ‘grown tired of always hearing Donna Juanita, Boccaccio, Le campane di Corneville, Giorno e notte’; the plot centres around the ambitions of a young convent girl to enter the operetta world, directly contrasting church and stage, sacred and profane.Footnote 34 Scarpetta’s play predictably involved music for both the church and operetta scenes, and Act II unfolds at Naples’s Teatro del Fondo with Nannina dressed ‘in very playful operetta costume, with bare arms and legs’, hunched over with shame at the sexualisation of the operetta stage.Footnote 35

Na santarella in turn became the basis for several further Neapolitan operettas, notably those by Crescenzo Buongiorno (Santarellina, 1889) and Gaetano Scognamiglio (Na santarella, 1889), the score to the latter surviving partly in manuscript.Footnote 36 This music is an obvious mixture of French and Italian influences in the sequence of marches, mazurkas, buffo duets, brindisi, couplets, Offenbachian ‘canzoni Pif Paf’ and concluding Galopps, and it also indicates the potential orchestration for early operettas – strings, clarinet, flute, trumpet, trombone, percussion and possibly also piano (Figure 1). Structurally, it is obvious that Hervé’s model was respected, but the rondeaux, chansons and couplets were largely replaced by a mixture of Italian and French forms that both localised and enacted a sexualised, parodic relationship with Hervé’s original. Act II thus opens with a metatheatrical celebration of operetta’s sexual allure by the ‘prima donna’ who declares that ‘If a man looks at me with a little smile, I’m cunning and respond with a languid little eye’ and a ‘Zingari’ number later on adds an exoticist element. Overall, the blazing success of Scarpetta’s work underlined and reinforced the growth of local operetta. In a single evening on 13 April 1890, the Teatro Nuovo would present the operetta Nu santariello at the same time as the Teatro Fenice offered Buongiorno’s Una santarella, and Na santarella’s success inspired a set of couplets by Giuseppe Giannetti that could be inserted in later performances.Footnote 37

Figure 1. Gaetano Scognamiglio, Na santarella (1889). Extracts from surviving piano–vocal score: Act I duet between Felice and Stella. Biblioteca Lucchesi Palli, Naples.

Naples and the nation

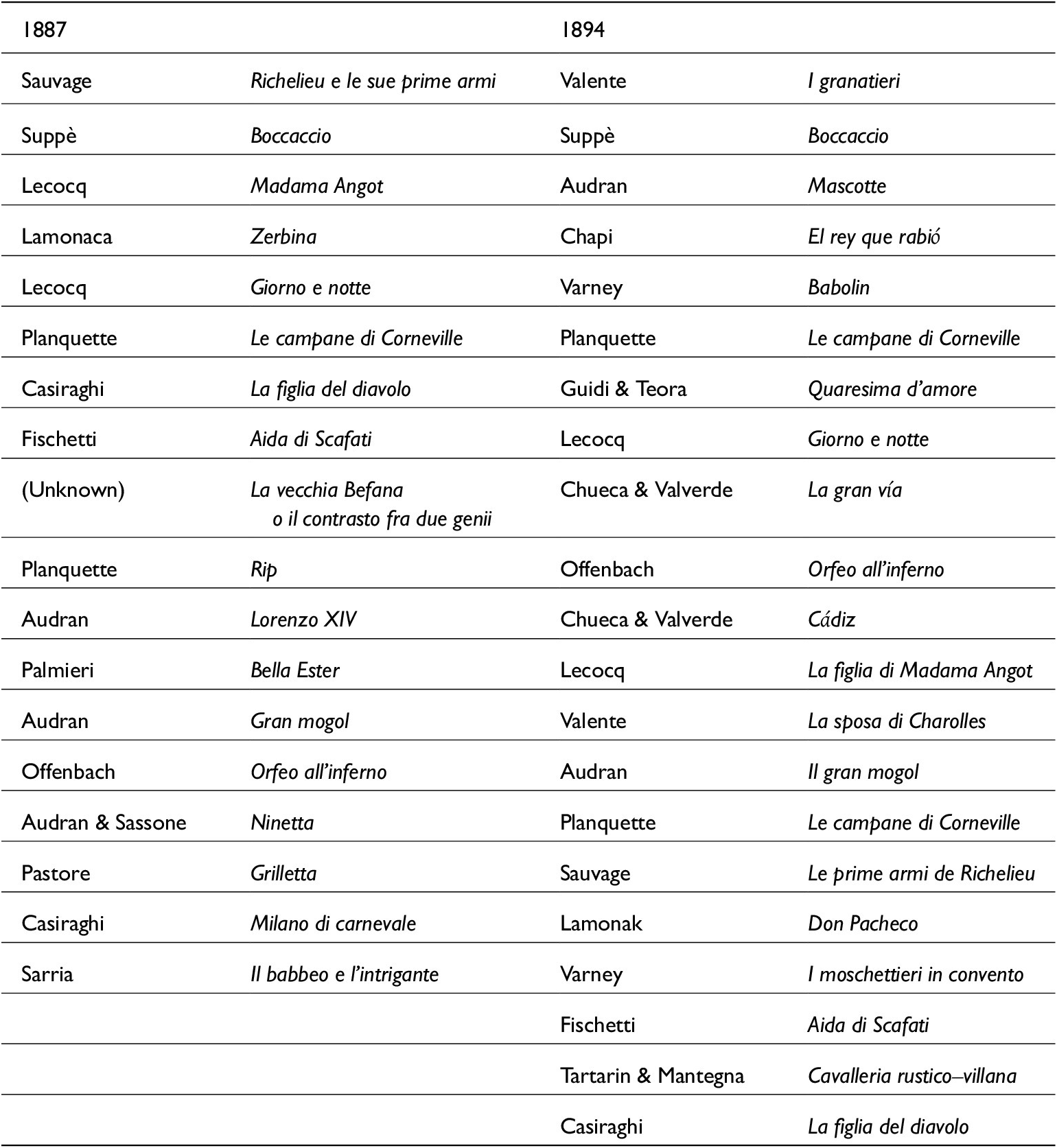

Language became a political fault line, and generative source of difference, in the post-unification Neapolitan operetta. During the 1880s and especially the 1890s, as elsewhere in Italy, a split was already emerging between companies that aimed at national and international circulation – combining older and new works – and those centred on a local audience alone. The first operetta companies had regularly presented works in both Italian and Neapolitan, as is clear from a mixed season of six works presented at the Teatro Nuovo di Varietà in 1880–1. But the situation soon began to change as the Italian government sought to increase national fluency in Italian, even if Neapolitan fared better nationally than Milanese or Roman dialect and would continue to enjoy a significant level of local prestige.Footnote 38 The 1887 season for Raffaele Scognamiglio’s leading Città di Napoli operetta company features typical programming for companies with national reach. Of the eighteen works presented, approximately half were Italian, including several premieres mixed in with works a decade or more old, and contributions from composers across the peninsula (Table 1).Footnote 39 Many of these were clearly inspired by French works in both plot and music (such as Ninetta, co-authored by the company’s music director Edoardo Sassone), and Sarria’s work – on an explicitly Neapolitan theme – was also recategorised as an operetta by the company.Footnote 40 The interplay between local and national was nonetheless foregrounded within Fischetti’s Neapolitan-language Aida di Scafati, in which the character of the princess Amneris speaks in Italian, in contrast to the rest of the cast.Footnote 41 The remainder of the company’s offering comprised mainly French operetta, a pattern that would persist over the following two decades in spite of the eventual success of Silver Age Viennese operetta. If placed alongside the repertory presented by the Città di Napoli at the Teatro dei Fiorentini in 1894, it is clear that a regular canon of local and foreign works – notably by Sauvage, Lecocq, Planquette, Casiraghi and Suppè – was emerging even as certain features were changing, and that a small number of parodies also continued to feature. Valente’s operetta was advertised without cuts or changes, while Guidi and Teora’s Quaresima d’amore was identified as the exclusive property of the company, indicating a growing sense of artistic seriousness and ownership. Alongside a selection of new French and Italian works, Spanish zarzuela also appeared with increasing frequency from the 1880s onwards, indicating that Naples – partly because of its Spanish heritage and in light of its mixed programmes – remained an obvious and major entry point for Hispanic music theatre.

Table 1. Città di Napoli seasons, 1887 and 1894; Annuario teatrale italiano per l’annata 1887 (Milan, 1887), 752–3; and Programmi Teatrali, Biblioteca Lucchesi Palli, Naples

Table 1 also reflects the fact that some of the most prominent Neapolitan figures on the Italian operetta scene had not only begun to premiere works outside Naples, but also begun writing in Italian, spurred on by the example of Maresca and others. Valente’s I granatieri premiered in Turin in 1889 and was set in Sardinia, while Lombardo produced a range of operettas in these early years, including Un viaggio di piacere (1891) and I coscritti (1892) – both in Italian, set abroad, and premiered outside Naples, even if they would soon appear on Neapolitan stages. Playbills from the Maresca and Lombardo companies indicate that, like the Scognamiglio troupe, during the 1890s these companies mixed a large number of French works with a growing number of Italian works of evident national appeal.Footnote 42 Maresca’s troupe had moreover embarked on a tour of South America in the late 1880s, and by the 1890s companies were touring across the entire Mediterranean region.Footnote 43 At the same time, these companies continued to premiere works by local composers within Naples itself. These works typically combined aspects of opera buffa, French operetta and Neapolitan song in a manner familiar from Scognamiglio’s Na santarella, while typically being in Italian.Footnote 44 For example, Scognamiglio’s Cappador (1892, premiered at the Politeama by the Maresca company), set in Spain in 1630, characteristically combined a ‘Serenata’ for the title character at the opening, an Act I stretta, the narrative ballad ‘Leggenda della strega’ and a ‘Concertato galoppo’ and Cancan concluding Act II.Footnote 45

In this context it is especially revealing that when Costa’s Le disilluse premiered in 1889, its librettist Roberto Bracco (1861–1943) – like di Giacomo, a prominent journalist, Neapolitan songwriter, librettist and playwright – praised Costa for carrying over the melodic vein he had already displayed in a hundred songs performed ‘to Neapolitan poetry and in the elegance of gilded salons’, while demonstrating sophisticated orchestration, sure theatrical sense and obvious Italianness. He continued: ‘I can’t deny the supreme respectability of any Italian artist who, in spite of trying to make in Italy some music that is fine, elegant, graceful, flirtatious, or sentimental or delicate, some of that music which is no longer abundant here, has the style and pride to continue to be eminently Italian.’Footnote 46 Bracco’s priority was not simply the question of italianità – despite his admiration for French operetta, he claimed not to see any trace of French influence in Le disilluse – but positioning operetta as a genre that was artistically and socially refined, in line with the social sophistication of Costa’s songs (which, though typically published as Neapolitan songs, evinced a drawing-room sensibility). Yet the work itself was in Italian and far removed from the street scenes of earlier Neapolitan comic opera – focusing on a marriage contest and unfolding in the non-specific time and place of a fairy tale, a ‘childish tale [bambinesca frottola]’ in Bracco’s own introduction – suggesting that Bracco and Costa already had their eye on a national market.Footnote 47 At the moment that Mascagni was turning to Verga’s Cavalleria rusticana as the basis for his breakout work, then, Neapolitan operetta composers were seeking to dominate a growing national market through a fusion of musical styles while avoiding overly local depictions.

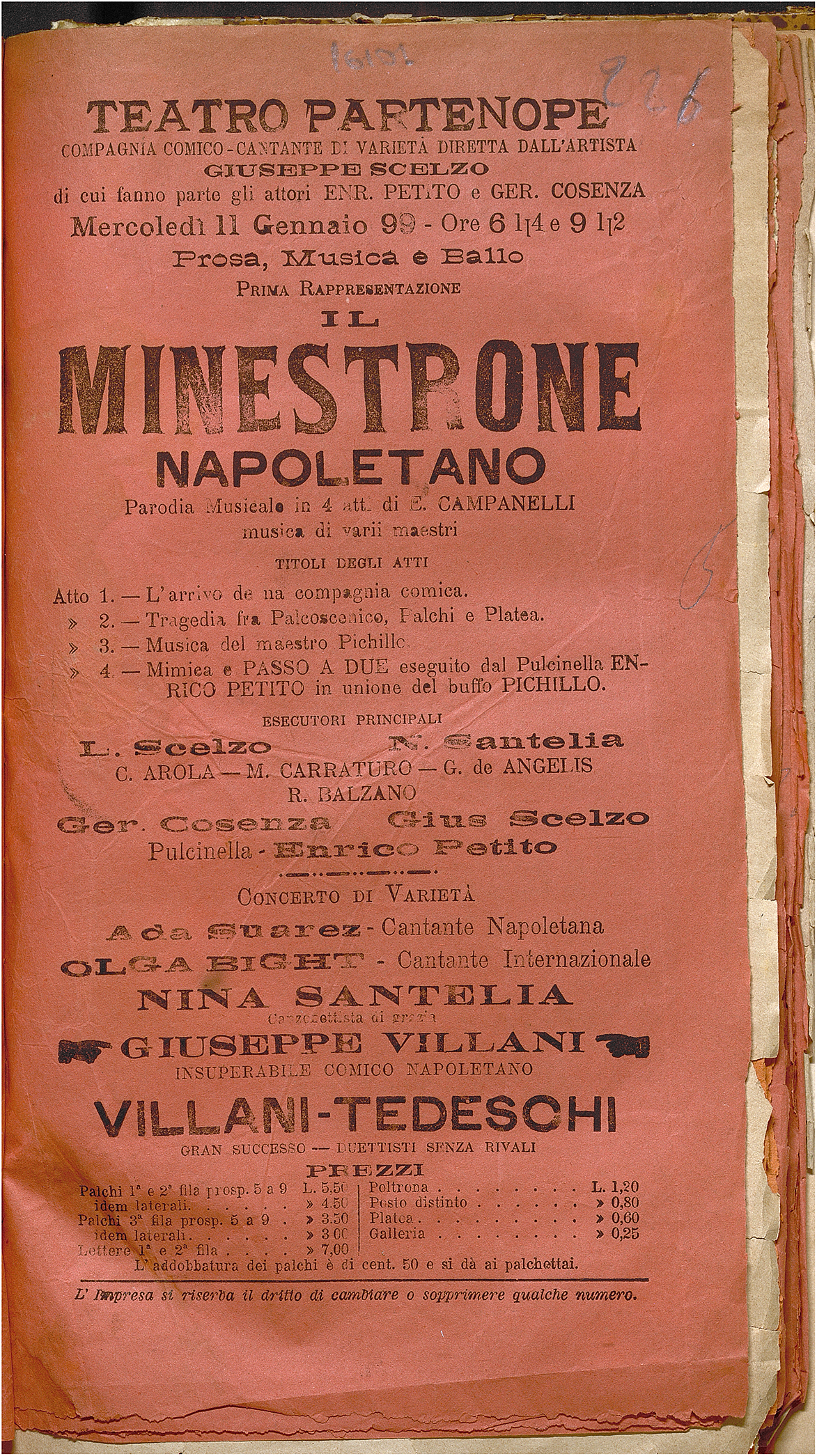

And yet, set against this trend towards national aspirations was the growth of local companies that continued to perform in Neapolitan and dominated the local circuits, particularly the Rossini, Partenope, Fenice and Sannazzaro theatres. Local companies in Naples run by Giuseppe and Luigi de Martino, Enrico Petito and G. Della Rossa, Aniello Balzano, Girolamo Guadiosi, Amelia Suarez, Teresina Cappelli and Giuseppe Scelzo performed across a range of mixed genres at regular venues, aimed at an expanding (if narrow) middle class but with some social flexibility indicated by the movement of companies between different theatres. They tended to describe themselves as ‘operetta’, ‘Neapolitan’, ‘comic’ or most commonly ‘varietà’ companies, and much of their ensemble was clearly drawn directly from the acting profession rather than opera – even if the description ‘comico-cantante’ was regularly incorporated into a company’s logo.Footnote 48 The tendency of Neapolitan opera buffa to stage Naples itself carried over strongly to these operettas. The Scelzo company, for example, presented Luigi Menzione and Almerico Vinaccia’s four-act ‘Grande féerie-musicale-spettacolosa’ Michele Strogoff con Pulcinella at the Partenope in March 1899, a work that unfolded across several continents – and included a Tatar camp – but opened at the opera house. Three months later it would offer Il minestrone napoletano, a ‘parodia musicale’ constructed by Errico Campanelli out of (most likely pre-existing) music by various composers, narrating the misfortunes of a comic theatre company that included Pulcinella (Figure 2).Footnote 49 Vincenzo Cunzo’s Venere in Turchia (1901), similarly, opened in Castellammare and appears to have involved an exchange between Neapolitans and Turks; following a duel, they return to Naples and the concluding part is set in a ‘café-chantant’. The Piedigrotta song festival could also become the direct subject of operettas, as in the ‘commedia musicale’ Piedigrotta presented in September 1901 at the Fenice by the Petito and Della Rossa company, with the two capocomici performing to a score again constructed from music by several authors.

Figure 2. Il minestrone napoletano, playbill. Programmi Teatrali, Biblioteca Lucchesi Palli, Naples.

Pulcinella shows had been the main activity of the San Carlino until its demolition in 1884, and the still-thriving Pulcinella tradition involved extensive use of music, including works that by the mid-1880s would be labelled operettas or commedie musicali. Footnote 50 Pulcinella also took centre stage in shows presented by companies more obviously aligned with operetta. Already in the early 1880s, for example, the Teatro Mercadante had presented both Bertaggia’s operetta La bisca di Montecarlo ovvero Il sogno di Pulcinella (October 1883) and the ‘commedia musicale’ Le metamorfosi di Pulcinella (February 1884). Pulcinella and Piedigrotta tropes could even be combined, underlining operetta’s importance as a vehicle for generating a collective imaginary through phantasmagoric and proto-surreal juxtapositions – what João Silva describes in his study of Lisbon as the scope for operetta to construct an urban imaginary through pleasure.Footnote 51 The mixing of different historical registers was clearly also frequent, whether through the appearance of Pulcinella in contemporary settings or the transformation of older works. Antonio Petito’s four-act ‘commedia musicale’ Masaniello o na seconna muta de Puortece con Pulcinella – seemingly a parody of Auber’s La muette de Portici – was thus announced in 1902 as having been performed nearly 300 times at the Teatro San Carlino, indicating a direct crossover between parody, pantomime and operetta.

What is more, this hybrid tradition evidenced a further connection between Naples and Paris. The commedia dell’arte had lingered on the Parisian boulevard scene via the character of Pierrot, and would become a further inspiration for various symbolist works throughout the 1890s.Footnote 52 This circulation drew connections between high and low cultures through a fascination with signification, and positioned commedia dell’arte figures as at once historical and socially and artistically disruptive. Tellingly, pantomime was a genre that Costa also explored when he composed L’histoire d’un Pierrot – the first of several prominent non-vocal works that included the ballet Bella Napoli (1907) – bringing together Parisian and Neapolitan practices at the Parisian venue that had once hosted Hervé.Footnote 53 The ‘Sérénade de Pierrot’, a waltz played on the mandolin, is a recurring theme and the Neapolitan quality returns in the form of a tarantella.Footnote 54 Pierrot soon secured a strong position in both Neapolitan and Italian markets, programmed first by the Teatro Varietà in November 1894 and then by pantomime companies throughout the mid-1890s.Footnote 55 Costa would be credited in the Italian press with infusing these pieces with a Neapolitan spirit regardless of their particular form.Footnote 56 But Pierrot underlined crucial factors, already hinted at with Le disilluse: Costa’s international profile and intermittent abandonment of his Neapolitan tongue would be integral to his ability to claim a national and international status for Naples.

Between operetta and song

At the heart of much of this crossover between operetta, opera buffa, dialect theatre and vaudeville was the shifting history of canzone napoletana, or Neapolitan song. The origins of the genre are regularly traced back to the early modern period and the development of Neapolitan folk music. Nevertheless, it is clear that the early nineteenth century and the rise of an international publishing market marked a definitive shift. A crucial figure was the Parisian Guillaume Cottrau, whose collections of songs (including his own) published under the title Passatempi musicali helped spread the genre internationally; his son Teodoro Cottrau was responsible for publishing the celebrated Neapolitan barcarolle ‘Santa Lucia’ in 1850. But it was the late nineteenth century that witnessed the emergence of a large number of composers identified with individual songs and the growth of an international market that would later be propelled by the nascent recording industry, positioning Neapolitan song as a node in an emerging global popular music industry.Footnote 57 Indeed, by the 1880s a consensus had emerged that Neapolitan song was entering a new era of its long history, thanks to a cluster of figures including Costa, Valente, Luigi Denza, Tosti and Lombardo.Footnote 58

Many Neapolitan songs were first linked to the Piedigrotta festival, an established part of the region’s musical mythology by the 1890s.Footnote 59 Neapolitan operetta thus emerged in tandem with the commercial ascent of the song genre; and while they clearly operated on significantly different scales, both genres seemingly offered a lighter alternative to serious opera (and even a modern alternative to opera buffa), even if their histories and audience demographics were hardly identical. This was encapsulated by Gaetano Scognamiglio’s La musica dell’avvenire (1885), which says goodbye to Rossini, Donizetti, Bellini, Mercadante and Petrella and implicitly proclaims Neapolitan song to be the true music of the future, even as the song itself – with its scherzando accompaniment, offbeat stresses and direct references to some of the greatest bel canto successes – was obviously shaped by variety theatre.Footnote 60 Writing in 1888, critic Agostino Ripandelli summarised a long-running critical thread that identified popular song as the true origin of opera buffa, arguing that French song in turn was the source of vaudeville.Footnote 61 Engagement with Neapolitan song – even in its later iteration – would mean returning comic music theatre to its roots, a path that other countries had (in Ripandelli’s view) failed to follow.

Neapolitan song has long had an ambiguous status in Italian intellectual history. As Martin Stokes has summarised, it was a genre that sat uneasily between the worlds of musica colta – to which it nonetheless had a relationship by virtue of its urban identity and its imitation in wider European music, shaped by Cottrau – and that of popular music, with Neapolitan song still bearing a significant connection with the Neapolitan lower classes and the world of folk music.Footnote 62 This bridging of high and low, in turn, has been linked by Goffredo Plastino with a longer intellectual tradition that saw Naples as a transitional space between modernity and a non-European south, exemplified by Walter Benjamin’s famous characterisation of the ‘porosity’ of Naples’s identity, in ways that position Neapolitan song as a dissolving point between urban and rural, musica colta and musica popolare. Footnote 63 Benjamin’s expression was derived from an essay co-written with Asja Lacis in 1924, following a six-month stay in neighbouring Capri (just two years after the premiere of Scugnizza). ‘Porosity’ was a term Benjamin used to account for the mobility and erasure of distinct social spheres he perceived in Naples, in contrast with the separation of spaces that typically characterise secular, rational modernity. This was an erasure he found in Naples in the blurring of public and private space, religious and secular, and across architectural and social practices, all resulting in a chaotic and theatrical environment. What defined the city in his view was ‘a theatre of new, unforeseen constellations’ where ‘the stamp of the definitive is avoided’ – ‘Porosity results not only from the indolence of the Southern artisan’, he summarised, ‘but also, and above all, from the passion for improvisation that demands that space and opportunity be at any price preserved.’Footnote 64

Benjamin’s formulation has been profoundly influential in studies of Naples and wider Mediterranean geographies.Footnote 65 Yet this perceived porosity was explicitly contrasted by Benjamin with Northern Europe, his ideas riffing on a discourse of Naples’s marginality and exoticism long perpetuated by writers from the North (especially as part of the Meridionalismo movement from the 1870s onwards). ‘Porosity’ as a theoretical lens has, unsurprisingly, been the subject of extensive debate and deconstruction – most recently by Ruth Glynn – in an effort to critique this Orientalist positioning and instead recognise the heterogeneous and diverse identity of Naples as an intellectual centre that decentres the European north.Footnote 66 Nonetheless, it is clear that the origins of Neapolitan song, and its complex social position, were a key concern among its leading literary contributors in the years around 1900, with debates centring upon whether the genre should be understood as a high literary genre or a folk one.Footnote 67 While di Giacomo argued clearly for the artistic origins of the Piedigrotta festival, Russo instead stressed its links with the Neapolitan working classes, a dispute echoing broader divisions over Naples’s intellectual history.Footnote 68 ‘Porosity’ unquestionably needs to be approached with caution. Yet placing Benjamin’s essay in dialogue with Neapolitan authors can sharpen our sense of the term’s usefulness –understanding it not simply as a mingling of high and low, but instead a dynamic and unstable interaction between cultural, social and artistic elements, old and new. This in turn positions Neapolitan song and the Neapolitan voice as a complex performance of history drawing together layers of the city’s identity – an ‘interstitial voice’, in Martha Feldman’s terms.Footnote 69

A further important stage in this history of canzone napoletana is its entry into the café-chantant. At the fin de siècle the Salone Margherita became a hub for café-chantant and new Parisian entertainments, as did the Eldorado, Eden and Sala Napoli.Footnote 70 As Paolo Sommaiolo has argued, the arrival of the café-chantant venue heralded a new ‘spectacularisation’ of Neapolitan song that would continue into the early 1920s.Footnote 71 Gianfranco Plenizio has moreover pointed to a growing influence of French operetta on canzone napoletana, including songs by Leopoldo Mugnone, Giovanni di Napoli and others destined for café-chantant that reveal unusual features such as two-octave ranges and countermelodies taken by the voice.Footnote 72 Neapolitan songs would also regularly be incorporated into macchiette (sketches) and variety shows, highlighting their early status as a theatrical (often metatheatrical) as well as purely musical genre, and anticipating the later development of the sceneggiata genre in the late 1910s.Footnote 73 Actor and singer Nicola Maldacea was a pioneer in developing the macchietta, often in collaboration with di Giacomo, and would also be involved with recitals of Neapolitan song: his presentation of ten of Valente’s hit songs from the 1897 Piedigrotta festival took place at the Gran Circo delle Varietà in August 1897, where he performed alongside Amelia Faraone and Diego Giannini.Footnote 74 Wider tours by Maldacea similarly indicate a tendency to combine sketches with rough assemblages of music, pantomime and dialogue.Footnote 75 Costa himself spent much of the 1880s establishing himself as a song writer via works including ‘Era de maggio’, ‘Serenata napulitana’ and ‘A frangesa’ that also became popular on the Parisian cabaret circuit, and a popular success such as Costa’s ‘Luna nova’ or Denza’s ‘Funiculì funiculà’ already incorporated an accompaniment part for chorus, clearly pushing the genre towards the theatre and ensemble performance.Footnote 76 As La tavola rotonda declared in 1892, Costa was ‘a Parisian in Naples’ and already at this stage it appeared likely that he would move on from the song genre to something more expansive.Footnote 77

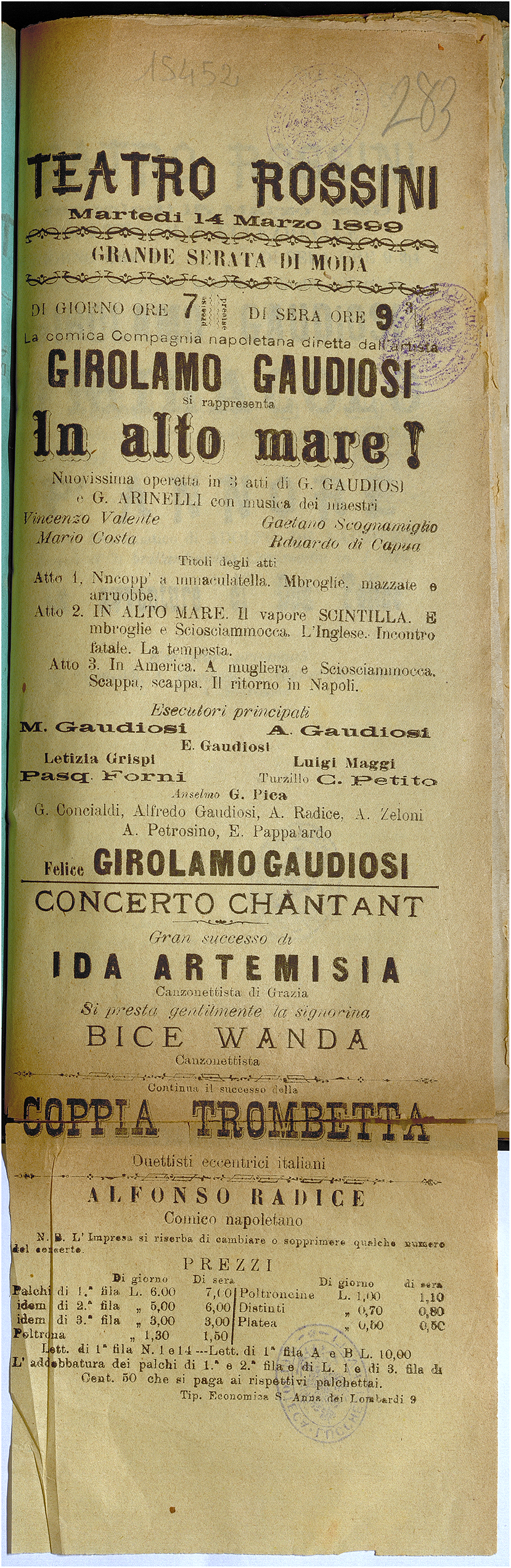

Exchange between opera buffa and Neapolitan song had been evident already in the late eighteenth century and was partly responsible for the apocryphal claim that Gaetano Donizetti was the author of the winning entry to the first Piedigrotta competition in 1839. Nonetheless, there was a clear commercial and discursive solidification of the link already by the mid-nineteenth century, a point at which opera buffa and canzone napoletana were both frequently considered to be entering a downward turn: the important collection La napolitana: Album di arie buffe, e canzone napolitane was published in the 1860s on the eve of the arrival of French operetta.Footnote 78 Operetta performances at the Nuovo and Rossini were also regularly followed by recitals of song, in addition to the use of Neapolitan elements in operettas composed for national circulation, and theatres frequently assembled songs into a longer narrative. Particularly compelling evidence for this comes from In alto mare! by Girolamo Guadiosi and Gennaro Arinelli, an operetta first presented at the Teatro Rossini in March 1899. This combined music by Costa, Valente, de Capua and Scognamiglio in a narrative that involved Neapolitans departing for America but eventually returning (Figure 3). Although neither libretto nor score have survived, the playbill notes the appearance of familiar Neapolitan types, particularly Felice Sciosciammocca, and was followed by several song acts. Given the operetta’s date and subject matter, it may even be that the music by di Capua included the famed ‘O sole mio’, which was published that same year.Footnote 79

Figure 3. In alto mare! Playbill (extract). Programmi Teatrali, Biblioteca Lucchesi Palli, Naples.

The activities of the Guadiosi company (a ‘comica compagnia napoletana’) are more broadly revealing of the highly fluid position operetta itself occupied between spoken theatre, opera buffa, pantomime and farce – a genre that could also encompass social realism and fantasy. Many of the shows presented were simply identified as commedie, ‘plays’, although these were typically followed by a range of musical and sketch acts drawing on a mixture of the company’s performers in the main show and other artists. But as Table 2 indicates, a significant number of their main shows at the Rossini were explicitly labelled as operettas or musical works, and reveal a wide range of generic headings as well as the return of Na santarella. Many of these were revived throughout the decade (the company relocated to the Fenice in the early 1900s). The performers were also actively involved in the organisation and composition of the shows, notably Arinelli and Davide Petito – the latter was the brother of Antonio Petito and thus a direct link to the legacy of the Teatro San Carlino.

Table 2. Girolamo Guadiosi company, selected musical shows in the 1890s. Compiled from programmes preserved in the Programmi Teatrali collection, Biblioteca Lucchesi Palli, Naples

The range of generic headings and the circulation of performers between sung and spoken works above all underline that a hard distinction between operetta and spoken theatre was essentially meaningless in smaller operetta theatres such as the Rossini and Sannazzaro, which also performed café-chantant and variety theatre.Footnote 80 With the exception of the most prestigious playwrights and theatre companies, plays at this time invariably featured music, song and dance; thus the generic label ‘operetta’ was more a matter of degree than kind in these venues. Even in larger theatres such as the Nuovo or Fondo that performed a more established body of works that drew on French operetta and opera buffa conventions, generic distinctions between opera buffa, opera comica, opera giocosa and operetta were frequently unclear; the proliferation of generic subcategories from the 1880s onwards highlighting their instability and the shifting prestige of ‘operetta’ as a signifier.Footnote 81 As Alessandra Campana has argued in relation to opera, music theatre raises particular generic challenges given its status as performance, and the Neapolitan scene in these years reveals both interchange between different generic types and also a frequent re-conceptualisation of genres through different performance modes.Footnote 82 The proliferation of generic titles also reflects the deeply noncanonical status of many works, clearly intended for short-term performance by a particular ensemble, and therefore not requiring the tighter standardisation associated with opera.Footnote 83 Above all the intermingling of old and new, music and speech, local and foreign practices, seems to suggest that operetta in and across Naples at this time should be understood more as a praxis than a strict classification, with competing definitions between social groups. If genre as a whole is ‘less of a pigeon hole than a pigeon’, as literary theorist Alastair Fowler has famously argued, operetta here indicates an entertainment incorporating a vast range of practices, with different configurations of originality and convention.Footnote 84

The relationship between Neapolitan operetta and Neapolitan song, moreover, highlights the challenges of any simple reading of the former in terms of class or aesthetic hierarchy, since it is clear that operetta encompassed a substantial range of venues, performance styles and languages. By the early twentieth century, ambitions to present operetta as a ‘middlebrow’ genre were clearly growing. Operetta, Naples’s Eldorado magazine concluded in 1905, was destined to be the comic, feminine counterpart to opera, full of ‘sweet music, supple like the adorable body of a sylph’ that would please male and female spectators alike.Footnote 85 The overt sexuality of many performances (such as Na santarella) was clearly a point of controversy among some critics, even if venues such as variety theatres were strongly defended in comparison with gambling venues – and works such as Le disilluse were explicitly framed as being artistically and socially refined. Arguments such as these were clearly a rhetorical move to identify operetta as a relatively elevated genre in ways that theatrical practice did not consistently support. At the same time, the social and generic status of canzone napoletana was also shifting by the early twentieth century, with many Neapolitan critics lamenting the commercialisation of Neapolitan song as it appeared to move further away from its connections with folk music, marginalising Piedigrotta as a centre of musical excellence.Footnote 86 Yet this commercialisation was also regularly described as a kind of elevation or formalisation of the genre. The Giornale dei teatri lamented the transformation that had taken place as ‘old Piedigrotta; of the people, classic … the spontaneous bacchanal of our people’ had become an increasingly upmarket event.Footnote 87 As with Le disilluse, Costa’s songs were clearly perceived to inhabit the upper end of a generically and socially amorphous field, and at his death Costa would be described as a figure who created ‘a kind of popular canzone that remained a romanza, a kind of romanza that remained a canzone’ – restoring to Neapolitan song its dignity without losing its ‘traditional and ethnographic’ aspects.Footnote 88

While Viennese operetta – particularly during the so-called Silver Age (1907–30) – may make for a compelling early case study of emerging middlebrow aesthetics, in the case of Naples such a framework can hardly account for all entertainments in this early period, even if it may align with more ambitious works presented by Maresca and Scognamiglio and even some operetta parodies.Footnote 89 What is more, the linguistic politics complicate this further: for if works in Neapolitan had significant appeal for local audiences, they always unfolded within a national framework in which Naples itself was an internal Other par excellence, at once culturally prestigious yet socially subaltern. The prominent role of Neapolitan song, itself enmeshed in questions about social and artistic status, adds yet more complexity. Neapolitan operetta’s relationship with canzone napoletana underlines that Neapolitan operetta often seemed to collapse generic and aesthetic distinctions rather than mediate smoothly between high and low.

Nationalising Naples in the Lehár empire

Following the Italian premiere of Lehár’s La vedova allegra in Milan in 1907, the operetta landscape in Naples (like elsewhere) would be transformed by the arrival of new works by Lehár and Kálmán. Naples had already been unusually receptive to the works of Johann Strauss in the 1870s, as Laura Moeckli has shown, and Viennese operettas became ubiquitous on the larger Neapolitan stages.Footnote 90 By 1911 (as indicated in Figure 1 of this issue’s introduction) nearly half of the operettas presented by the Città di Napoli would be Viennese, significant ongoing local production notwithstanding.

Unsurprisingly, this arrival of new Viennese operettas provoked renewed anxiety among those composers and critics keen to defend the emerging Italian tradition, which was apparently both threatened and simultaneously stimulated by this foreign onslaught.Footnote 91 On the one hand, the trade journal L’argante could herald ‘Il risorgimento dell’operetta’, with the genre entering the leading theatres across the country and finally overcoming its dependence on poor singing and staging.Footnote 92 On the other, Lehár’s success could also be seen as destroying a native operetta tradition that was still in the process of emerging, with a stream of Italian authors again declaring that the origins of operetta were unmistakably Italian: rooted in the tradition of Rossini, Donizetti, Rossi, Cagnoni and others, and with critics demanding a greater interest in local composition.Footnote 93 Within Naples, operettas on a blatantly Viennese model – such as Leoncavallo’s La reginetta delle rose (premiered in Rome, 1912) – would similarly be framed as a continuation of earlier Neapolitan tradition, even as venues such as the Salone Margherita had long juxtaposed canzone napoletana with French and Viennese musical entertainments.Footnote 94

The actual basis for such an Italian operetta was widely debated, however. Writing in a series of articles in L’opera comica, composer and critic Arturo de Cecco was adamant that local operetta was hard done by in Italy. De Cecco had recently premiered his Sicilian-set operetta Conca d’oro (1907), and would later have a significant success with Funiculì, funiculà (1921) – its title clearly alluding to Denza’s song that had helped to launch the canzone revival in the early 1880s (and the operetta itself featuring a centrepiece at Piedigrotta). For de Cecco, only two Italian operettas had truly matched the commercial success of French works – namely Valente’s I granatieri and Costa’s L’histoire d’un Pierrot, ‘which although not presented as an operetta, cannot be considered as anything but of the operetta genre’ – because young composers were not encouraged to try their hand at it.Footnote 95 This gesture towards Costa’s Pierrot highlights both its place in the operetta repertoire, and the strong connections between Italian operetta and pantomime that had been established since the 1870s, in itself arguably a legacy of the strongly gestural tradition in Italian stage acting.Footnote 96 Leaning again on Italy’s opera buffa history, de Cecco argued that Italian operetta required the same gifts as opera – music that should be ‘brief, sparkling, original and melodic’ – and that the rest was the responsibility of the librettist.Footnote 97 Developing his argument in a subsequent issue, de Cecco was clear where composers could find their inspiration:

But if we in Italy wanted to make operetta as they do elsewhere, it would be good enough just to give the job to any lazy layabout, because in Naples on the day of Piedigrotta, once the festivities are done, he would go through the streets collecting – without the least bit of discrimination – all the scraps of the newspapers and magazines and booklets and postcards. Without doubt, in those papers that served for the mad joy of an exalted people for just one day alone, you’d find enough material to write not just one, but thousands of those operettas that come with such arrogance from across the Alps.Footnote 98

This was hardly a straightforward plea for the re-use of existing music, and indeed indicated a growing desire for operettas to be constructed out of entirely original material: de Cecco’s complaint was aimed directly at the ‘industrial’ production of operettas in Germany, England and the USA, which increasingly included the use of Neapolitan song forms.Footnote 99 De Cecco’s dismissal of the national success of a growing number of figures, moreover, has the strong ring of professional competition. It reflected the competing claims of regional musical traditions (such as the Venetian barcarolle) and touring operetta companies (such as the Città di Milano) to establish successful operetta conventions across Italy – as had already been evident with dialect companies in the 1880s and 1890s. But de Cecco’s argument did stress that local inspiration for operetta scores was close to hand and that operetta’s music should be fundamentally accessible – even mistakeable for popular song. De Cecco’s final plea was for composers to recognise the distinctive quality that made operetta alive: its malleability and its use of speech. For whereas opera repeatedly had to rely on music for dramatic impetus, operetta could rely on speech to move the action forwards; and whereas operas (in his view) were doomed to die when a new operatic ‘system’ emerged, operettas were intrinsically flexible in a way that allowed them to survive.Footnote 100 Implicit in this was a sense of the established adaptability of Italian operetta, and that the genre as a whole might be more fully developed through the macchietta or even the pantomime – and an acknowledgement that aspirations towards a more through-composed model (or one relying on the opulence of opera) misunderstood the genre. The increasing decadence of opera would need to be countered by the fecundity of a genre that could find its source material directly in the streets, adapting itself to the changing times while expressing the Italian character.

De Cecco’s was of course not the only perspective. Similar claims were certainly made elsewhere in the national press, in response to arguments that Neapolitan song was both too autonomous and insufficiently sentimental for the modern, opulent and Viennese-influenced operetta genre.Footnote 101 In August 1909 Giovanni Ressmann delivered a call to arms to native composers to engage with the genre, and to compose works that would be ‘sparkling and graceful’ as part of the ‘risorgimento dell’opera comica’ – even as he took for granted that this would likely involve the adaptation of Viennese waltzes, the most successful dances of the time.Footnote 102 Yet in an article published in L’arte drammatica in July 1913 and reprinted from Trieste’s newspaper Il piccolo della sera, journalist and librettist Ettore Moschino firmly declared that ‘The Italian spirit, the genius of our language, the lack of appropriate types prevent us from entering with much success in a genre where the principal requirements must be frivolity, bizarreness, sometimes nonsense, and carefree madness.’Footnote 103 In Trieste, this article had already prompted a survey of several contemporary operetta composers over the future prospects of the genre, among them Costa, Ivan Darclée and Carlo Vizzotto. Native success in the genre would require re-engagement with either Rossinian opera buffa or Goldonian spoken theatre, away from the indeterminate genre and sex of operetta (l’operetta senza sesso). Operetta was again torn between opera and spoken theatre, hampered by its inherently mixed medial status; and while for some a truly Italian form might emerge in dialogue with foreign imports, for others such as Moschino it was clear that only a return to native practices would suffice – whatever those practices might be.

Opera buffa had itself been given something of a new life in the early twentieth century with the rise of Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari and works such as Le donne curiose (1903), which engaged directly with the Goldonian comic tradition as well. Yet Wolf-Ferrari’s commedia-dell’arte-inflected works were transparently intended for the operatic stage and, moreover, reflected the composer’s Venetian heritage, meaning they could hardly be considered a continuation of Neapolitan tradition. At the same time, the growth of the gramophone industry in the early 1900s involved the recording and international distribution of Neapolitan songs, aligning the genre with an emerging popular music industry.Footnote 104 As critics debated the ideal direction of Italian operetta, however, the international success of Neapolitan song did indicate that Italy already possessed a genre that could compete with the waltz or the cancan, the tango or the foxtrot: a genre that also moved into the theatre and increasingly narrated its own global circulations via songs about Italian emigration. Prior to the arrival of Silver Age operetta, Luigi Dall’Argine’s national hit Dall’ago al milione (Rome, 1904) had already juxtaposed a ‘canzone italiana’ and a ‘barcarola del marinaro’ with a selection of waltzes, while Costa’s erstwhile librettist, Bracco, penned the libretto for Giulio Ricordi’s Pulcinella innamorato (1907). Operettistic engagement with Naples also offered a contrast with the verismo that had defined the early 1890s, painting the area not primarily as a site of violence but rather one of sensual pleasure, beauty and intense nostalgia. Much as Andalucian regionalism had become a marked feature of zarzuelas following the Spanish–American War in 1898 – a region that could stand in for the nation, shaped by its circulation in French artworks – Italian operetta followed a broadly similar path in evoking Neapolitan music, despite the divisions that attended the genre within Naples.Footnote 105 Explicitly marked as regional, canzone napoletana could serve both as a national signifier – one that could moreover absorb other regional genres such as the Venetian barcarolle within it, as witnessed by ‘Santa Lucia’ – and as part of a growing global popular canon, one that operetta troupes equally sought to enter.

Napoletana, come canti tu!

With this in mind, let us return, finally, to Costa’s Scugnizza. This work’s Neapolitan engagement emerges in a significantly different light when considered against the longer narrative related above, as do Costa’s operettas from the late 1910s and early 1920s – works acclaimed as the true starting point of an operettistic canon, yet emerging startlingly late in the genre’s history. Already in 1919, L’operetta had expressed a wish that Mario Costa – ‘Italian, but also deliciously Neapolitan’ – could offer ‘a strictly Neapolitan subject, in order to coordinate and ground the folkloric aspects of the libretto with that of the music and produce an operetta of our own customs and character’.Footnote 106 And by the early 1920s, Naples was established as a – arguably the – starting point of an Italian operetta tradition, yet it was a tradition endlessly in need of re-establishment in light of international trends.

Following the First World War, anxieties over operetta’s Italianness had become more pronounced, and even stronger arguments were made for defending Italian operetta from the incursion of foreign imports. Regionalism also became increasingly widespread in operettas intended for a national audience, evident in works such as Darclée’s Amore in maschera (1913), Giuseppe Pietri’s L’acqua cheta (1920) and Ferdinando Paolieri’s Bacco in Toscana (1923).Footnote 107 Costa had returned to operetta with Capitan Fracassa in 1909 – although in many ways the work was highly French in influence, being an adaptation of Théophile Gautier with a gavotte, madrigal and drinking song (among others) that give the impression of a revival of Auber rather than Rossini, and it used a plot that had been dramatised by Giovanni Valente (brother of Vincenzo) twenty years earlier.Footnote 108 In contrast, Costa’s next two operettas, Il re de chez Maxim and Posillipo, reused many of his existing songs and dances under the stewardship of Carlo Lombardo, underlining the extent to which operetta could now function as a means of circulating songs to a wider marketplace, while updating an approach long familiar on the local Neapolitan stage. Notably, neither work was premiered in Naples, and they were instead staged at Milan’s Teatro Fossati and Rome’s Teatro Eliseo respectively. Il re de chez Maxim patched Costa’s songs together to produce a typically Parisian and Monégasque-set work that blatantly alluded to Lehár’s greatest hit and was dismissed by several critics for its clichéd libretto, even if Costa’s music was praised. Posillipo focused on the encounter between an English woman and a local Neapolitan, with Act II set at the Piedigrotta festival.

It was Scugnizza a year later that became the major national and enduring success, an operetta explicitly centred on the encounter between musically talented Neapolitan street urchins and North American visitors – that is, the idealised Italian past and an urban modernity represented now by the USA rather than Paris, reflecting the long history of emigration from Naples to the Americas. The central hit and refrain of the work is the foxtrot ‘Napoletana’, introduced in Act I, which celebrates the vocal power of the Neapolitan street urchin. This complements Totò’s ‘mandolinata’ in Act II by evoking Naples in familiar ways, with traditional folk instruments added to the modern orchestra. Yet in many ways the designation ‘foxtrot’ also challenged distinctions between musical genres and highlights the commercial nature of Neapolitan song itself by 1922: the piece was rapidly excerpted as a separate dance number (Example 1). Another regularly excerpted piece was the ‘Shimmy’, in which the American character Chic teaches Salomè the latest dance moves, allowing modern American dances to be included diegetically.Footnote 109 At the opening of Act II, as they entertain the Americans in ‘antique’ costumes, the Neapolitan characters explicitly narrate their own trajectory, from dancing minuets to embracing American dances, and pinpoint Naples as a site of nostalgia: ‘a picture of Naples from long ago / revives American strangeness’.Footnote 110 Indeed, a comparison of Scugnizza with earlier operettas exposes how self-conscious the use of Neapolitan song had become as an Italian operetta signifier, and its own close relationship with an international and global marketplace.Footnote 111 Where Mamma Angot al Costantinopoli had tied Neapolitan song to French operetta in a Turkish context, Scugnizza directly acknowledged the new musical and economic superpower.

Example 1. Mario Costa, ‘Fox trot della scugnizza’, Scugnizza, piano–vocal score (Milan, 1922). (Minor engraving errors corrected without comment.)

Ironically, for all that critics acclaimed Scugnizza as an innately Italian operetta, its Neapolitan setting and music was paired with American music and tied to a structure clearly informed by Lehár, with its double pairing of sopranos and tenors and its clash of high and low society, in a manner familiar from works such as Zigeunerliebe (1910). Hybridisation had been at the core of the Italian operetta enterprise from the start, and it was precisely Costa’s (and Lombardo’s) awareness of foreign trends that had allowed him to conquer the national market (Lombardo’s similar awareness is explored by Marco Ladd in this issue). Yet ironically, it was this international orientation that would finally damage Costa’s success in the local market that had been his professional starting point. Scugnizza would fail in Naples no less painfully than Giordano’s Neapolitan verismo opera Mala vita had done thirty years earlier, rejected for its stylised, picturesque take on Naples’s musical culture that was transparently intended for audiences elsewhere.Footnote 112 Scugnizza stood in glaring contrast to the realist trend in local stage works such as Raffaele Viviani’s Tuledo ’e notte (1918) and Campagna napoletana (1921), which sought to depict the impoverished areas of the city and its countryside while incorporating songs and musical accompaniment. Viviani (1888–1950) had enjoyed earlier success with Francesco Buongiovanni and Giovanni Capurro’s Neapolitan song ‘O scugnizzo’ (1906), a figure he would later make the central figure of his play L’ultimo scugnizzo (1931). While Viviani’s dialect works continued to appeal to a local audience, works by Costa were clearly aimed at a national one and were moreover evidence of the consolidation of operetta by the 1920s as a separate branch of the Neapolitan entertainment sector from variety shows, opera and spoken theatre.

Scugnizza, then, exhibits clear continuities with Neapolitan works from decades past but also crucial differences, differences that reveal much about the evolving Italian operetta scene and Naples’s changing role within it. The continued use of Neapolitan song in operetta from the 1870s onwards both acknowledged the canzone’s ambivalent status and could function as an origin story for a musical genre – operetta – that was itself distinctly modern. However much critics returned to the need to ground an Italian light opera tradition in earlier comic opera, the recurrent use of Neapolitan song and Neapolitan settings suggests a counternarrative in which operetta was conceived as emerging more directly from song, particularly metatheatrical song – even as Neapolitan opera buffa and parody had long held structural similarities with French operetta that destabilised clear generic distinctions. The featuring of Neapolitan song within operetta thus highlights the theatrical nature of Neapolitan song itself – framing Neapolitan song as a form of history, and a performative construction of Neapolitan identity – but it also demonstrates the tendency for operetta to splinter into easily separated numbers in a way that was much closer to revue. This was a trend evident already in Naples in the 1870s and 1880s, and it would ultimately determine the genre’s fate in the 1920s. Furthermore, the national tinge that Neapolitan song could give operetta was transnationally formed, as witnessed by the turn to British and American principal characters in both Posillipo and Scugnizza, although it had already been a quality of such works as In alto mare! And this national flavour was something from which a figure such as Costa, who had accompanied Italian operetta from its beginnings in the 1880s to the 1920s, could readily profit. When Il re delle api arrived in Rome in early 1925, Il giornale d’Italia concluded that it offered ‘the ineffable delight of the heart and the senses, the rapture of our music pure Neapolitan music, which is like saying Italian twice over’.Footnote 113

As critics throughout this period debated the origins, directions and worth of Italian operetta, the genre’s self-consciousness about its own hybridity and artifice – its historical awareness and its generic uncertainty – might in the end be its most distinctive quality. This self-consciousness on the part of Italian operetta’s constituent actors registered with particular force in Naples, a city renowned for its theatrical life and urban theatricality, if highly sensitive to its status as former capital. Italian critics may have longed for an opera buffa revival, but Neapolitan operettas offered a fleeting engagement with contemporary life while providing a local contribution to an emerging international entertainment industry. This was ultimately made explicit in works such as Scugnizza that directly juxtaposed Italian and American popular music styles. While ‘porosity’ has proved enduring as a framework for studying Naples, the theatricality integral to Benjamin’s analysis is perhaps most useful in helping us to understand the Neapolitan operetta scene. The self-conscious performance of different registers and styles, and the multiple authors and voices that make up many of these works, resulted in works that were ready to be broken up and remade through new voices, stories and sounds, and even through new genres. Neapolitan song – the theatrical vocal expression of a city famously sidelined and neglected in the newly-formed Italian state – could both be a witness to Italian operetta’s Italianness, and expose the fragmented, mediated nature of any construction of that Italianness.

Focusing on Italian operetta thus has the potential to shed new light on familiar Italian opera. Operetta forces us away from familiar operatic geographies and uncovers parallels (and divergences) in subject matter between opera and operetta that bear witness to the preoccupations of Italian middle classes in this period. But Italian operetta also exposes the competing dynamics at work in the construction of genre, dynamics that may ultimately militate against its survival when the different social ‘planes’ fail consistently to align. The eventual long-term failure of works such as Scugnizza to enter the international – and even entirely local – canons reveal this clearly. Operetta might have promised to offer a version of the middlebrow for Italian and Neapolitan audiences – albeit one always contested. But despite its fleeting success across the Mediterranean and South America, Italian operetta soon proved irreconcilable with Italy’s increasingly established place in global musical hierarchies as the home of Italian opera and canzoni napoletane, with little ground between. And the flexibility that made Neapolitan operetta so vibrant in its earliest decades also proved unsustainable once generic conventions around operetta began to harden. Operetta’s own porosity was thus both its greatest strength and its greatest weakness. It enabled operetta to flourish – until the need to choose between art music and popular music, opera and canzone, left it stranded in a no-man’s land.

Acknowledgements

Research for this article was partly carried out during a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellowship at King’s College London (September 2019-September 2023). I would like to thank Sarah Hibberd, Roger Parker, Terence Sinclair, Martin Stokes, Gavin Williams and the fellow contributors to this special issue for their feedback on earlier versions of this article.