No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

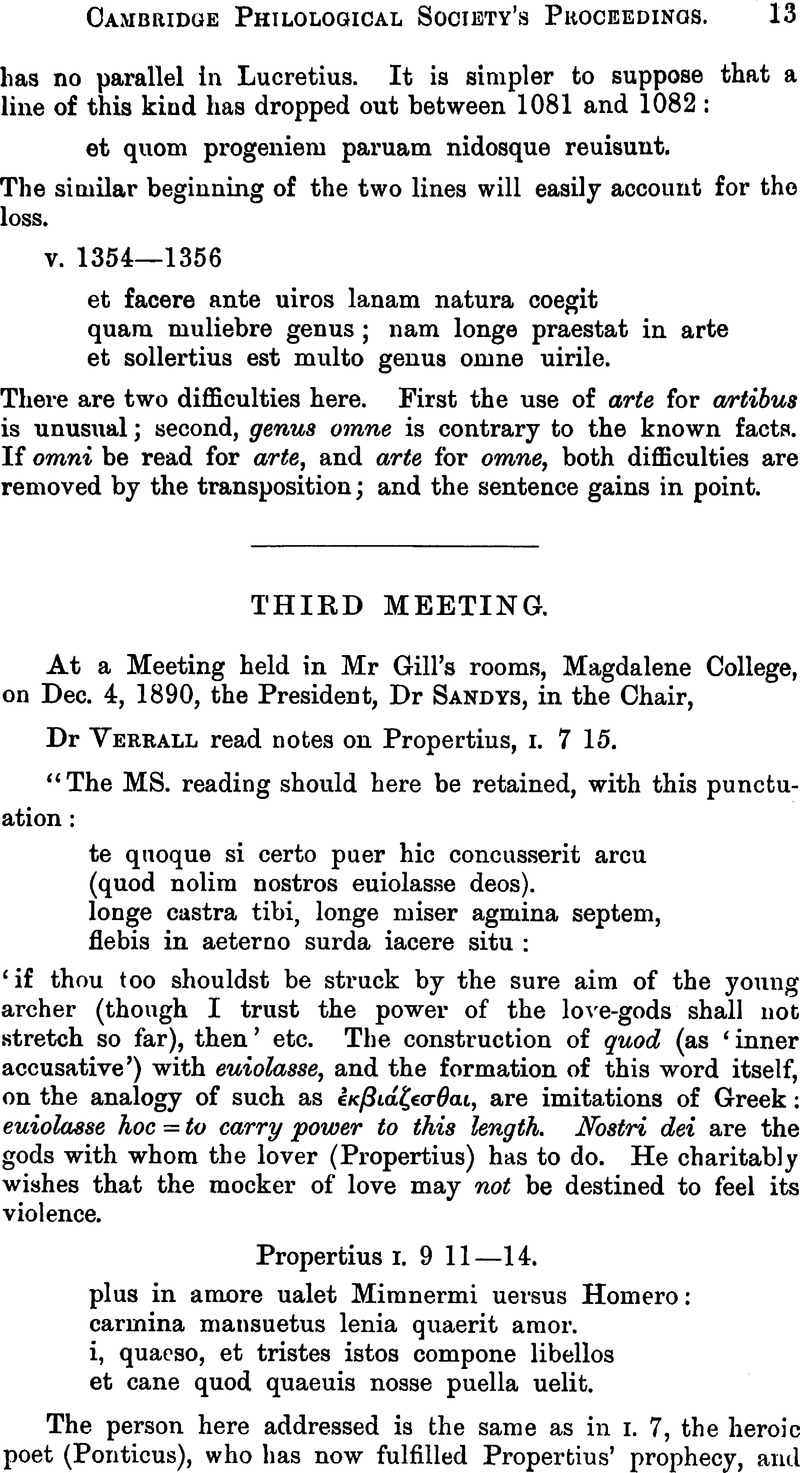

Third Meeting

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 April 2015

Abstract

- Type

- Michaelmas Term, 1890

- Information

- Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society (First Series) , Volume 25 , January 1890 , pp. 13 - 21

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author(s). Published by Cambridge University Press 1890

References

page 15 note 1 Johansson's attempt (K.Z: 30, 422) to maintain a connexion between μîσος and miset is not very successful.

page 16 note 1 Since this was written the theory has received Prof. Brugmann's assent. In a paper before the Königliche Sächsische Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften on Dec. 9,1890, and subsequently published in their Berichte(1890, p. 205 ff.) he adds several examples to those given by Zimmer from Italic (including the new inscription). These will be noticed below.

page 18 note 1 To these Brugmann (Berichte d. K. S. Ges. Wiss. 1890, p. 214) would add pihafei, herifi covortuso, benuso, which are certainly forms of the same class, and seste ise and (with the r kept) adpener, which seem to me more doubtful.

page 18 note 2 Lamatir is used with no subject in the curse of Vibia but in the Tab. Bant, with esuf ‘ipse’ which occurs elsewhere as a nominative, but may be indeclinable. If it is nominative it shows that in later Osean the construction of this old legal form had been assimilated to that of the regular passive.

page 19 note 1 Osthoff, Morphol. Untersuch. V (preface)Google Scholar has already suggested that the mā- of māgnus represents ![]() I should prefer to derive it from

I should prefer to derive it from ![]() which would be in harmony with what we know so far of the representation of the long sonant nasals in Latin (gnātus = I. Eu.

which would be in harmony with what we know so far of the representation of the long sonant nasals in Latin (gnātus = I. Eu. ![]() tos); it is likely that some sound is lost before the m, probably s- (cf. miror: Skt. smáyatē, etc.), from the Homeric scansion of μέγας which lengthens a preceding short vowel some 200 times (v. Munro, Hom. Gram. § 371–2). Then the a of magnus must have invaded an original *megis (also *me(gh)-ior?) and *meximus, if the latter is the original of this Osean form. I am bound to add that Brugmann regards Osc. messimo- as standing for *medh-simo- ‘midmost’, which would make equally good sense here, but contradicts Bartholomae's law (Bezz. Beitr. XII. 80Google Scholar, cf. also Verner's Law in Italy, p. 42), that every -d + s-, -t + 8-, etc. in Osean became -tt-. This need not however apply to -dh- + -s-.

tos); it is likely that some sound is lost before the m, probably s- (cf. miror: Skt. smáyatē, etc.), from the Homeric scansion of μέγας which lengthens a preceding short vowel some 200 times (v. Munro, Hom. Gram. § 371–2). Then the a of magnus must have invaded an original *megis (also *me(gh)-ior?) and *meximus, if the latter is the original of this Osean form. I am bound to add that Brugmann regards Osc. messimo- as standing for *medh-simo- ‘midmost’, which would make equally good sense here, but contradicts Bartholomae's law (Bezz. Beitr. XII. 80Google Scholar, cf. also Verner's Law in Italy, p. 42), that every -d + s-, -t + 8-, etc. in Osean became -tt-. This need not however apply to -dh- + -s-.

page 19 note 2 The form cἱdῦἱς occurs on another inscription which is a gcod deal earlier (eiduis luisarifs Büch, . Rhein. Museum, XLIV. 1889, p. 326Google Scholar; is this an Osean name for the ‘ploughing-, furrow-month’ (Lat. lira, loesa, Germ. geleise) i.e. September?) and this (not to mention the Greek form, acc. pl. ειδούς, gen. ειδῶν), seems to show that the word was originally an o- stem, and presumably masculine. What caused its change of gender and declension? The former, I should suggest, was adjusted to that of Kalendae and Nonae; the latter to that of such words as quinquatrus, septimatrus, and, further tribunatus, etc., with the group senectus, Juventus, etc., originally simple -tu-stems; Bücheler, who compares these last, regards the u declension of idus as an extension of its stem, comparing Jan-us: Janu-aruts; which after all comes to much the same thing, since all such extensions are analogical to start with.

The d, even more than the eἱof eἱdůἱs shows that the old derivation from aidh- ‘to burn’ must be abandoned. Bücheler holds that it originally denoted a band, or gathering of some official kind, and that its meetings gave the name to a particular day of the month, as the Osc. půmperiae seem to have done: cf. gladiatoribus ‘on the day of the games’. He suggests that the root may be that of Gr. οιδεῖν.

page 20 note 1 This view of sakrafir is the one adopted by Brugmann, who however says nothing as to the construction of ůltiumam.

page 20 note 2 Unless we reckon the deponent karanter (pai humuns bivus karahiter) in the Curse of Vibia (Zvét. It. Inf. no. 129).

page 21 note 1 If Brugmann's explanation (loc. cit.) of covortuso, benuso, as standing for *covortus sor *benus sor, where sor is the parallel form to Latin sunt, is correct, this form in Umbrian has preserved the thematic o.