Introduction

The US-Chinese trade war represents the most severe economic conflict in modern times. In 2018, under the former US Trump administration, the United States began the trade war by unilaterally increasing tariffs on a range of Chinese goods.Footnote 1 As China reciprocated by similarly elevating tariffs, bilateral trade cooperation has utterly deteriorated. The resulting economic and political costs for both domestic economies are substantial and more broadly threaten the prospects for cooperation between these two major powers.Footnote 2

Strikingly, this conflict still prevails under the new US Biden administration. Even though the current US president's orientation differs from the former in nearly every policy area, the overall confrontational approach toward China is not relinquished. Firstly, most of the tariffs initiated by the Trump administration have yet to be lifted. Second, at a more fundamental level, China has been targeted in recent rhetoric accompanying nearly every major policy decision of the new administration. Biden's gigantic infrastructure project, as well as his “Buy American” initiative, have been framed as an opportunity to challenge China's growing economic clout.Footnote 3 Even though economically costly, why is the United States so adamantly pursuing conflictual trade relations with China?

Different answers can be derived from the existing literature to answer this question. Although neoclassical economics argues trade to be beneficial in aggregate terms, the existing literature argues that the United States, especially for some citizens, has incurred economic losses through open trade with China. These so-called China shocksFootnote 4 have led to manufacturing job and wage losses for some American citizens.Footnote 5 The economic downturn due to the global financial crises is argued to have exacerbated preexisting economic vulnerabilities.Footnote 6 This literature inherently sees trade conflict between the United States and China as a function of these material losses for domestic individuals and groups.

To understand the role of mass public opinion in the context of the US-China trade, some other explanations can also be advanced. On the level of individual attitudes of the mass public, there is somewhat more limited evidence about the importance of such individual economic factors, although they are occasionally argued to interact with other concerns. Instead, individuals are argued to form their views based on individual social-psychological predispositions or sociotropic attributes.Footnote 7 Increasingly, the interaction between material and nonmaterial factors is being studied.Footnote 8 Thus, at the individual level, a broad range of material and nonmaterial explanations have already been advanced to understand the rising US animosity toward maintaining open trade with China. Despite a number of studies, inter alia Spilker, Bernauer, and Umana; Chen, Pevehouse, and Powers; Bush and Prather; Gray and Hicks; and Li and Zeng,Footnote 9 taking the perception of the trade partner further into account, most of the literature is preoccupied with finding individual-level explanations that vary at the individual level of analysis.

While the US initiation of the trade war has been publicly justified for a range of economic reasons, the prevalence of rhetoric about China's broken trade promises accompanying the trade war between the United States and China is striking. Most public propositions advocating a confrontational economic approach toward China are accompanied by the notion that China has not kept to its word in trade in the pastFootnote 10 by breaking the agreed upon terms of trade, for example by not sufficiently liberalizing its economy or government procurement rules.Footnote 11 Thus, as China is argued to have broken many trade promises, upholding protectionist measures is portrayed publicly as a fair response.Footnote 12

This article contributes to the existing literature on the US-China trade war by systematically studying the effects of such rhetoric about the unreliability of the trading partner. The current academic debate on the US-China trade war, as well as research on protectionist attitudes more broadly, do not take the ramifications of political rhetoric about the trading partner sufficiently into account. While various sources of trade cooperation attitudes have been explored, the aspect of unreliability of the trading partner has not received enough attention in the trade attitudes literature. Specifically, the potentially perilous effects of discussing unreliability in upholding past trade promises—that prevail strongly in the context of the US-China trade war—are largely unexamined. This omission, with the notable exception of Chen, Pevehouse, and Powers (Reference Chen, Pevehouse and Powers2019), is surprising because even though invoked frequently in political rhetoric, to my knowledge, the effect of such broken trade promise rhetoric for US-Chinese trade cooperation support specifically remains unexplored.

This article therefore examines how this type of rhetoric prevalent within the US-China trade war context shapes individual trade cooperation support toward the other trading partner, the United States or China. I argue that such rhetoric is likely to have crucial effects because it decreases the level of trustworthiness of the trading partner. To this end, as individuals are likely to hear about deviant trade behaviour through news media, I start by illustrating salience of such discussions in US-Chinese trade news from a mainstream news source 1978 until the end of 2019. Then, I examine the effects of broken trade promises of different trade partners in original parallel survey experiments with members of the mass public from the United States and China, the two countries involved in the trade war.

The findings suggest that the rhetoric featuring past broken trade promises adopted to justify the launch of the US-China trade war has important ramifications for bilateral trade cooperation support. Trade cooperation support varies according to the other country's past behaviour. The findings reveal that individuals from both countries react more strongly to unreliability than reliability in trade behaviour. Most of these effects operate independently of the political alliance or identity of the other country. These treatment effects do not vary according to the level of generalized trust or most of the other common sociopolitical individual-level characteristics. Importantly, the perceived level of trustworthiness of the other country diminishes considerably when confronted with past unreliability.

Importantly, within the context of the trade war between the United States and China, not only issues about trade have been raised but also accusations applying to other policy realms. I similarly find that discussions of promise breaking beyond the issue area of trade policy have the potential to affect trade cooperation support. In an additional conjoint study, I find that discussing transgressions also in other issue areas, such as military affairs and human rights, decreases respondents trade support. Past behaviour in environmental and cultural affairs seems to matter less that the aforementioned areas. Individuals’ evaluation of past trade behaviour is therefore not just narrowly concerned with promises in the area of trade but also extends across various issue areas. Trade attitude formation is therefore multidimensional. To explain the surge in animosity toward trade with China, a broader perspective going beyond just the US-China trade interaction is therefore necessary.

These findings shed some light on the potential causes and consequences of the US-China trade war. Contextual factors about the past behaviour of the trading partner—in this case China and the United States—seem to matter. Specifically, trustworthiness is affected by discussions of broken trade promises. When the other country has not kept to its word in the past, the trading partner will be perceived as less trustworthy. Thereby, support for trade conflict is more likely when the trading partner country has been unreliable in its past behaviour. Support for the US-China trade war is therefore likely to occur on the grounds of such fairness perceptions. Furthermore, these findings highlight why despite reaching a Phase 1 deal, returning to more cooperative US-China trade relations is tricky.

More generally, these studies suggests that mobilizing against trade with China in this manner is likely to have more long-lasting effects that will go beyond the US-China trade war as such. Political rhetoric targeting past broken promises in trade policy rules and interactions severely inhibits cooperation support because it reduces how trustworthy the other country is perceived. Especially in the US-Chinese case, continuously deteriorating trust is problematic because the world's two largest powers and economies are involved. Also very recently, China has been prominently accused on not abiding to its trade promises of the Phase 1 trade deal.Footnote 13 This article highlights the importance of these contextual factors and how fundamental fairness concerns shape the most important trade confrontation of the twenty-first century.

US-Chinese trade rhetoric

Recent political rhetoric surrounding US trade policy has vociferously targeted China for breaking trade promises. Already in public debate leading up to the unilateral increase of tariffs on Chinese goods, demands for creating a “level playing field” between the United States and China were rife in US public debates.Footnote 14 This outcry suggests that some US observers perceive the bilateral trade relation to be fundamentally unfair. The main complaints span domestic and international economic policies. First, even though China's President Xi Jinping promised to “let market forces play a more dominant role,” many argue that these promised economic reforms are insufficient or have stalled.Footnote 15 Second, the trade imbalance between the United States and China is argued to be unfair as China does not buy enough from the United States resulting in a US trade deficit with China.Footnote 16 Accordingly, this demand featured prominently in Donald Trump's Phase 1 trade deal.Footnote 17

This rhetoric is supported by some prominent voices claiming that China has engaged in breaking trade policy rules. In the international trading system, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) plays an important role in enforcing the agreed upon rules. This includes monitoring, informing, and punishing trade rule violations.Footnote 18 Also, a trade policy review body of the WTO evaluates member countries’ abidance to WTO rules.Footnote 19 One of the most pivotal developments was China joining the organization in 2001, which involved committing to WTO rules and implementing economic reforms.Footnote 20 Twenty years after China's accession, EzellFootnote 21 writes in a scathing report that “China has failed to meet numerous WTO commitments” (p. 1) in nearly all areas of trade policy. Similarly, LardyFootnote 22 argues that economic reforms have stopped or slowed down contradicting Xi's 2013 promise to let market forces play a more dominant role.

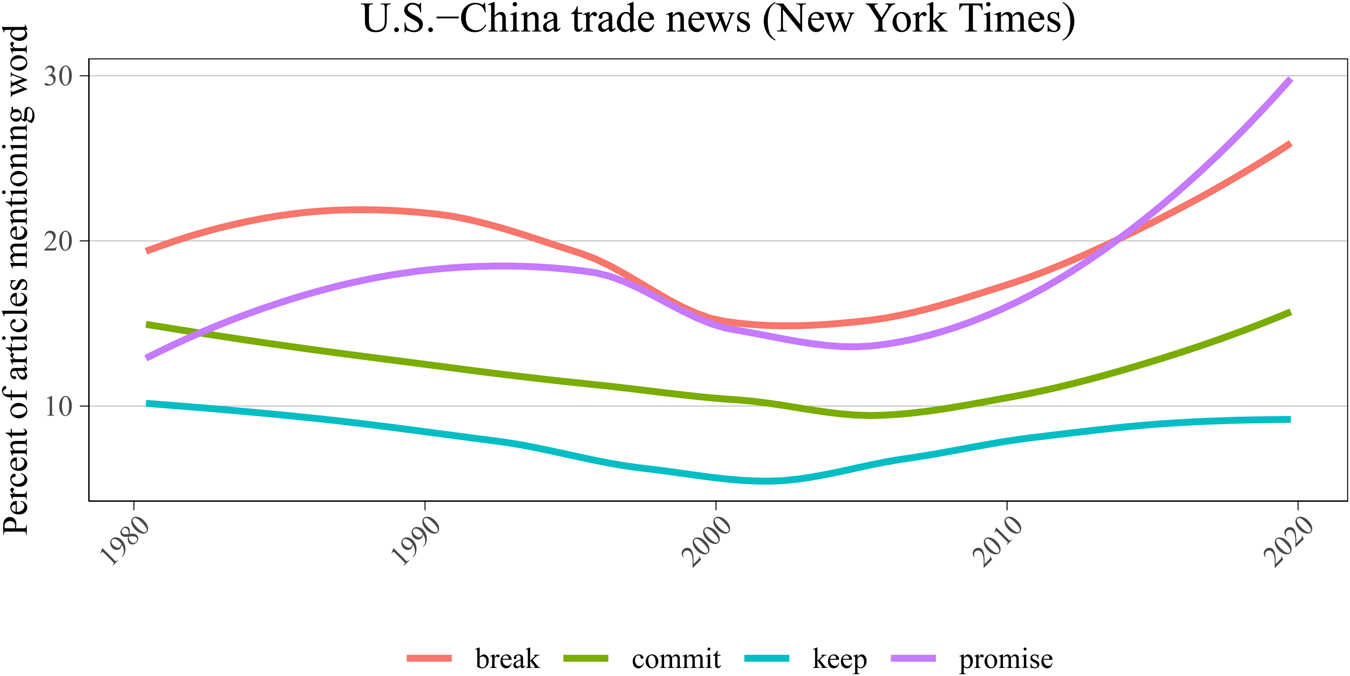

The negative rhetoric is noticeable even in mainstream US news reporting. Figure 1 shows the over-time proportion of articles mentioning the words “break,” “keep,” “promise,” and “commitment” in news about US-China trade in the New York Times.Footnote 23 News media are important for the elite-public opinion link. First, they represent one of the main sources of information for the mass public.Footnote 24 In this vein, news media content is often presented according to the views of elites.Footnote 25 As the key conduit between the public and politicians, media play an important role for telling people what to think about.Footnote 26 Articles from news media therefore offer an important and accessible source for gauging salient topics.Footnote 27 The New York Times can be considered an important US outlet, which has been discovered to deliver relatively neutral reporting of domestic and international developments and events.Footnote 28

Figure 1. Frequency of the words “breaking,” “keeping,” “promises,” and “commitments” in bilateral trade news from the New York Times.

It is therefore striking that in New York Times bilateral trade news reporting, the proportion of articles mentioning “breaking” and “promises” increases noticeably over time.Footnote 29 The proportion of articles mentioning “breaking” is lower in bilateral trade news articles in the years shortly after 2001 when China joined the WTO. Discussions of “breaking” and “promises,” however, increase after this year and continue to expand as Donald Trump assumes presidency and begins the trade war in 2018. Until this day, even under the new Biden administration, accusations of China not keeping its word to the Phase I trade deal prevail.Footnote 30

Nonetheless, other researchers, though increasingly less prominent in public debates, still argue that China has not broken rules in trade policy. For instance, Johnston,Footnote 31 summarizes statistics from the OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators report and the Design of Trade Agreements Database (DESTA) that suggest that China has liberalized most of its trade and concluded deeper trade agreements over time. Even though he concedes that “there are persistent WTO incompatible non-tariff trade barriers” (p. 102), he nonetheless finally concludes that China is “moderatively supportive” (ibid.) of the trade order and thereby has not engaged in major trade promise violations. Even though a lively debate continues on whether China is a rule-breaker, rule-taker, or rule-maker, the consensus in public debate seems to be increasingly tilting toward the view that China has actively engaged in breaking trade rules. Interestingly, in media accounts within China, the perception prevails that, by unilaterally increasing tariffs, the United States has broken its own liberal trade promises and engages in unfair trade behaviour toward China.Footnote 32 HopewellFootnote 33 even extends this logic and argues that the United States can currently be considered as the revisionist promise-breaking power.

Regardless of the degree of the veracity of the criticism targeting China, this rampant negative rhetoric surrounding the US-China trade war is likely to shape individual attitudes toward bilateral trade cooperation. The malleability of individuals’ views to such cuing effects of negative elite rhetoric cannot be underestimated.Footnote 34 Importantly, prospect theory suggests that individuals are sensitive to losses and exhibit negativity biases.Footnote 35 Whereas both individual cognitive tendencies are closely related, LevyFootnote 36 explains that the former “refers to overweighting of negative values while the latter refers to the overweighting of negative information.” Both tendencies are likely to be at play when individuals hear about broken trade promises. Therefore, while some of these accusations toward China may be ambiguous, individuals from the mass public are unlikely to accurately assess these complexities of trade policy, as most members of the public generally know little about trade.Footnote 37 This lack of knowledge makes balancing opposing views even more difficult.

However, when elites target the unfairness of trade with China so conspicuously in their rhetoric by focusing on allegedly broken trade promises, individuals from the mass public are likely to form negative views about trade cooperation with China. Particularly, negative rhetoric, focusing on broken trade promises, is likely to be more influential than positive rhetoric focusing on kept trade commitments. An asymmetry in behaviour evaluation is thus likely to prevail:Footnote 38 Discussions of negative unreliable past behaviour are likely to have more of an impact than highlighting positive reliable past behaviour. That is, discussions of unreliability are more likely to elicit punishment than reliability is met with reward.

The public debate surrounding the US-Chinese trade conflict raising such unfairness cues have not received enough attention within the existing academic literature on the trade war. A large part of the literature on the US-Chinese trade conflict focuses on an assessment of material losses due to open trade. Even though trade makes countries wealthier in aggregate terms, some societal groups or sectors gain and others lose from trade competition and lobby the government accordingly for more or less trade liberalization.Footnote 39 Within the open economy politics framework, individuals’ preferences for liberalization or protectionism affect the policy outcome through domestic political institutions and processes.Footnote 40 Accordingly, animosity toward China is argued to grow due to individual economic losses usually depending on the individual's sector of employment.Footnote 41 Despite the overall reduction of consumer price goods, job and wage losses stemming from open trade with China have important redistributional consequences enforcing structural inequalities, that is trade wars are class wars.Footnote 42

Nonetheless, economic reasons for opposition and negative rhetoric have the potential to interact and reinforce each other. On the individual level, the distinction between a causal mechanism driven by unfairness concerns as opposed to rational material explanations is not necessarily clear cut. For instance, individuals may link unreliable trade behaviour, for example if the other country “cheats” and does not provide reciprocal market access,Footnote 43 to economic losses for domestic workers or even themselves individually.

This research contributes to expanding our understanding of contextual explanation because these explanations differ in terms of expected outcome variation. The economic explanation expects variation between individuals with different skill levels or other socioeconomic attributes. The broken promise rhetoric explanation, however, is assumed to resonate across of broad range of individuals with different levels of education and skills. While contextual factors are related to seminal existing sociotropic explanations highlighting, for example, out-group anxiety,Footnote 44 the empirical focus often remains on identifying relevant individual-level attributes. For these explanations, contextual factors play an indirect role because they address concerns about the country as a whole. This article expands this view by explicitly addressing contextual factors pertaining to the other country to complement existing research on individual-level attributes and sociotropic factors.

This article is not the first to examine the importance of contextual factors. Some other research also strongly suggests that contextual factors specifically involving negative rhetoric shape trade cooperation support. Carnegie and CarsonFootnote 45 argue that spreading “compliance pessimism,” featuring prominently during the Trump presidency, leads to subsequent “defections,” that is noncooperative policy responses. On the level of individual attitudes, Chen, Pevehouse, and PowersFootnote 46 demonstrate that individuals and elites from the United States care strongly about past broken trade promises and expect other democracies to keep their trade commitments. Moreover, political side-taking of other countries shapes individual economic attitudes.Footnote 47 Other recent International Political Economy (IPE) and International Relations (IR) work also studies how reputation shapes interstate cooperation.Footnote 48 However, most IR reputation studies focus on the reputation of the own, rather than of the other country.Footnote 49 These studies focus on reputation in the sense of domestic audience costs incurred by a leader in relation to their domestic public.Footnote 50 Individuals are theorized to seek consistency between commitments made by their leaders and that these domestic leaders incur political costs if they back down from a previously made statement or commitment.Footnote 51 In relation to this important literature on reputation, I essentially argue that besides these “domestic” audience costs, corresponding “foreign” audience costs, that is of the other country, also exist.

Building on this important reputation research, which takes the perception of the trading partner and its past behaviour more into account, I correspondingly advance the view that such rhetoric within the US-China trade war context shapes views toward bilateral trade cooperation. Important previous work has also discovered that fairness concerns, in the sense of both equality and equity, prevail for individual economic attitudes.Footnote 52 These fairness concerns are likely to arise when hearing about another country's unreliability, that is that it has not kept to its word in the past. This work suggests that individuals exhibit fundamental fairness concerns when it comes to trade policy. The robustness of these findings suggests that these fairness-driven views have the potential to be held independently of the specific trading partner.

The causal mechanism studied in this article encompasses that discussions of promise breaking are likely to diminish support for trade cooperation support by affecting how trustworthy the trading partner is perceived. Research from social psychology reinforces this perspective, as it proposes that discussions of promise-breaking behaviour destroy cooperation by affecting trustworthiness perceptions.Footnote 53 Trustworthiness, in contrast to generalized trust, has received less attention in IPE studies of attitudes toward cooperation that predominantly gauge the effect of an individuals’ trust level on policy views.Footnote 54 A key definition of trustworthiness is the belief that a promise by the other actor can be relied on. While generalized trust can be seen as an attribute of each individual, trustworthiness is about the relation with the other actor and more malleable.

This mechanism is likely to extend beyond the issue area of trade policy to security and other realms of interaction between the United States and China. To the extent that the perceived degree of trustworthiness of the trading partner, such as China or the United States, is affected, generic perceived unreliability is likely to matter. That is, the trade war is not just about trade as individual views are likely to be shaped not just by discussions of promise breaking in Chinese or US trade behaviour but also within other issue realms. These fairness concerns are potentially general and might spill over across various issue areas.Footnote 55 Current discussions of China involve not just trade but also military affairs, human rights, culture, and the environment.Footnote 56 More generally, some existing studies have shown the importance of deviating past behaviour attitude formation in the realm of environmental cooperation.Footnote 57 Powers and RenshonFootnote 58 also look at the importance of different issue areas, but in the context examining the effects of international status loss. In the same vein, discussing unreliable behaviour in other issue areas is similarly likely to spill over and shape individual trade attitudes toward the other country.

This discussion has the following two implications I explore with survey experiments. I first expect members of the mass public to support cooperation less when they hear about promise breaking and to support cooperation more when they learn about promise keeping in trade. Given some empirical findings from prospect theory, I assume that the negative effect will be more pronounced than the positive effect (H1). I thus expect that the trading partners’ keeping or breaking of trade promises affects the perceived degree of trustworthiness perception of the other country. Second, the ramifications are likely to prevail beyond the issue area of trade narrowly, as trustworthiness issues are not just trade specific. Discussions of violating promises in other issue realm, such as human rights, military, environment, or culture, are likely to decrease the likelihood of support for cooperative trade responses (H2).

• H1: Individuals from the mass public are likely to more strongly punish unreliable behaviour than reward reliable behaviour.

• H2: Individuals’ trade cooperation views are likely to be shaped by promise-breaking rhetoric targeting other issue realms beyond trade.

Research design

To test these expectations, I use a survey experimental design to be tested in the two countries involved in the trade war, the United States and China. This methodology is ideal to systematically test the causal mechanism of trustworthiness I seek to examine. In a survey experiment, the object of study is systematically varied so that the effects of this variation can be gauged on the outcome.Footnote 59 In my case, this corresponds to varying whether the trading partner has broken trade commitments, as articulated by some in the context of the US-China trade war. However, as the previous discussion on China's past trade promises reveals, some observers maintain that China has also upheld some its trade promises.Footnote 60 That is, within the experiment, the past behaviour of the other country is varied; the country is either reliable, unreliable, or no further information about its past behaviour is disclosed.

To assess whether these effects change across various identities of the trading partner, the United States and China, respondents are either confronted with an ally, adversary, no information about the other country or, respectively the United States (for Chinese respondents) or China (for American respondents). The latter allow me to test directly how the specific identity of the countries involved in the trade war, the United States and China, shape the responses toward trade cooperation. These country label treatments increase the external validity of my results and enable me to gauge what difference is made between other abstract countries compared to the other contending power.Footnote 61 Thereby, this design allows examining to what extent the causal mechanism is generalizable to other adversarial or allied countries or potentially specific to the US-China context.

I acknowledge the trade-offs when mentioning real as opposed to abstract countries. This research, however, is not only interested in isolating the effects of the past promise breaking and keeping but also interested in understanding what happens when the actual country is argued to be doing the promise-breaking keeping, as in the US-China trade war context. Especially when seeking to understand the trade war between these two countries better, also mentioning the countries involved in the conflict is crucial. I therefore have a total of (4 × 3 =) 12 treatment groups, as displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Overview of the treatment combinations

The outcome variable is whether respondents would support signing a new trade agreement with that country. This response is given on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from –3 (“strongly oppose”) to +3 (“strongly support”). Also, respondents can indicate that they don't know. To study how the perception of trustworthiness of the trading partner is shaped by such behaviour, I ask respondents after they have answered the outcome variable: “How trustworthy do you regard the other country in the aforementioned question?”Footnote 62 Respondents have the following answer options, which are coded from +2 to –2: Highly trustworthy, Somewhat trustworthy, Not very trustworthy, Not trustworthy at all, or don't know.

The treatment text is about signing a new trade agreement with the other country that has either engaged in promise breaking or keeping (or no info = control) within trade policy in the past. For all these scenarios, the potential trading partner affirms that it will keep the terms of the prospective new agreement. Although I acknowledge that the latter may induce a certain commitment to reliability, I opt for this option because the outcome question about support for trade cooperation, as well as the whole treatment about discussing a prospective trade agreement, would be less realistic and credible without mentioning this pledge.Footnote 63 In the real world, a country is unlikely to discuss a new trade agreement with another country without pledging, at least initially, to keep the terms of the trade agreement. The precise treatment text (for the US sample) is shown in the following text:

The United States is considering signing a trade agreement with another country, [no further information, a political ally, a political adversary of the US, China]. This trade agreement's purpose is to facilitate the exchange of goods and services between the United States and the other country. The prospective agreement includes many promises in the realm of trade policies for both countries, for example decreasing tariffs on traded goods which decreases prices of goods for consumers and increases exports. Particularly in these areas the other country has a history of [keeping, not keeping] its promises it made previously.Footnote 64 The other country has pledged on many recent occasions that it will honor specifically the terms of this prospective trade agreement with the US.Footnote 65

The survey experiments are conducted in the United States and the People's Republic of China (PRC). I selected these two countries because they represent the world's two largest trading nations engaged in a power transition and trade war. Global trading relations are likely to be significantly shaped by how fickle trade cooperation support is from these two great powers. Additionally, my studies have real-word relevance because both countries have accused each other prominently of not keeping to their word in trade policy. Therefore, to the extent that these trade issues are salient, a better understanding of citizens’ attitudes toward trade cooperation is necessary. This necessity is further highlighted by the trade war, which has also been highly salient in Chinese media and debates.Footnote 66

While most survey (experimental) studies rely on a US sample, very few survey trade or economic attitudes in Mainland China.Footnote 67 Even though the PRC is not a democratic regime, there are good reasons for studying mass public opinion even in such an authoritarian context.Footnote 68 Even though elections do not take place, the Chinese Communist Party still relies on the public's support—or at least its strong lacking disapproval—to sustain its rule.Footnote 69 A growing body of research indicates a certain degree of responsiveness to concerns of the mass public.Footnote 70 Because increasing open trade has played a crucial role in elevating living standards in the past few decades,Footnote 71 current trade threats represent a potential risk for China's economy, and, ultimately, its one-party rule. Accordingly, ShirkFootnote 72 portrays China as a “fragile superpower” for which especially relations with the United States have the potential to become “hot-button” issues. More empirical insights are therefore needed from the main rising power and trading nation.

The generalizability of the effects of promise breaking

In a second more complex study, respondents are asked to compare two trade agreement proposals. The proposals vary with regard to the following dimensions: the political alliance, the existing level of trade, and the country's past behaviour in different issue areas. These different issue areas are military affairs, human rights, cultural affairs, environmental issues, and international trade. Moreover, the projected economic growth attained by the trade agreement varies. I select these areas because they refer to relevant issues areas, which are more or less related to trade, however all occur in public debates about China and the US-China trade war more broadly. By varying these multiple dimensions at the same time, I intentionally introduce more complexity and noise. This study allows me to examine whether the mechanism generalizes to other issue areas beyond trade.Footnote 73

I leverage this choice-based conjoint experiment to identify individuals’ multidimensional policy preferencesFootnote 74 that are likely to prevail in the US-China trade context. As the outcome variable, respondents are asked which proposal they prefer and then to indicate how much they prefer it. Two proposal combinations are shown in the survey. Furthermore, a series of covariates are measured before the experiment. Aside from some common social demographics, I measure generalized social trust with the commonly used battery of items.Footnote 75 Other measures include age, gender, employment, level of education, nationalism, and political ideology. In China, I also ask whether individuals are members of the Chinese Communist Party.

I rely on samples collected in November 2020 using the survey platform Qualtrics (n = 4,181 in total).Footnote 76 The respondents were recruited by the survey company IPSOS. Both samples are representative for key sociodemographics, such as age, gender, employment, and region. Of course, it is important to note that collecting survey answers during the COVID-19 crises has some implications. While there is some evidence that respondents are less attentive than in nonpandemic times,Footnote 77 “experiments replicate in terms of sign and significance, but at somewhat reduced magnitudes.”Footnote 78 Owing to this evidence, I am not strongly concerned that the timing of my studies produces wrong findings as a false negative seems likelier than a false positive. The subsequent section describes my findings from both parts of the survey.

Findings

The findings of both experiments highlight how promise-breaking rhetoric in the context of the US-China trade war has the potential to shape support for trade conflict. In both parts of the analysis, I find evidence for the importance of promise-breaking rhetoric for views on US-Chinese and Chinese-US trade cooperation. The survey experiments in the United States and China reveal that (1) mentioning promise breaking severely reduces trade cooperation support, (2) the positive effects of discussing promise keeping are smaller, and (3) that these aspects prevail amongst respondents, especially in the United States, regardless of the trading partner. Such behaviour strongly affects the perceived level of trustworthiness of the trading partner. Finally, the results of the conjoint suggest that these aforementioned effects prevail for promise breaking in other issue areas apart from trade, especially in military affairs and human rights.

The effect of unreliability on bilateral trade attitudes

How does this heightened salience of promise-breaking trade rhetoric, as often argued in the US-China trade war context, shape individual views toward bilateral cooperation? Overall, this section suggests that emphasizing promise breaking diminishes the prospects for cooperation support by targeting the perceived level of trustworthiness of the other country. This dynamic is largely independent of the identity of the trading partner.

Figures 2a and 2b display the average treatment effects of the treatments—reliable, control, and unreliable—on the outcome variable measuring support for concluding a trade agreement with the other country. As a reminder, the outcome variable is coded from –3 (“strongly oppose”) to 3 (“strongly support”). Please compare the Appendix for descriptive statistics for both samples.Footnote 79

Figure 2. Mean response of participants according to Past Behaviour Treatments for the Outcome Variable Bilateral Trade Cooperation Support (“To what extent do you support your country signing a new trade agreement with the other country?”).

Respondents of the US sample respond strongly to unreliability. Support is highest when the other country has kept to its word. Compared to the control group, unreliability diminishes their average level of trade cooperation support by about 30 percent. The magnitude of the marginal gain when receiving the reliability treatment is much smaller. Thus, a strong asymmetry prevails in the response.

While the general tendencies are similar for responses from the Chinese sample, this asymmetrical response is somewhat less pronounced. The average support for the trade agreement with the other country in the control group, that is when no mentioning of reliability was made, is nearly 50 percent higher than amongst US respondents. Still, like in the other sample, most respondents’ reaction to positive past behaviour is weaker than toward negative past behaviour.

This tendency is somewhat supported when examining the results of the effects of the treatments on the response to the manipulation check about the other country's trustworthiness in Figures 3a and 3b.Footnote 80 Compared to the control group, keeping promises increases the perceived level of trustworthiness of the other country amongst citizens from both countries. Correspondingly, broken trade promises diminish how trustworthy the other country is perceived. Interestingly, the effects are slightly more pronounced amongst US than Chinese citizens. This suggests that US citizens react more strongly toward such promise-breaking rhetoric.

Figure 3. Mean response of participants according to Past Behaviour Treatments for the Manipulation Check (“How trustworthy do you regard the other country in the aforementioned question?”).

But how do these past behaviour effects vary when taking the identity of the trading partner into account? To study this question, I study the effects of the trading partner and past reliability/unreliability. Thereby, I focus on the interaction of the other country's past behaviour with the identity of the other country. The corresponding regression table findings are presented in the Appendix Section 6.5 “Tables Corresponding to Results in Figure 4a and Figure 4b,” which show the effects of the past behaviour and trading partner treatments on their own and in interaction with each other. I find that the identity (political alliance) shapes the responses (support for trade agreement) to some extent, compare Figures 4a and 4b.Footnote 81 When confronted with unreliable past behaviour, US responses do not differ statistically significantly between allies (effect size approx. 0.4), adversaries (approx. 0.2), or the specific mentioning of China (approx. –0.1). The clearest difference occurs in the control responses. Here, the responses toward allies (approx. 1.6) differs statistically significantly from responses toward China (approx. 1.1). These treatment effects do not vary according to the level of an individuals’ generalized trust, compare the Appendix.

Figure 4. Responses to past behaviour and country identity treatments. These models visualize the interaction effects between past behaviour and identity of the other country. (Behaviour*Country Identity) on Bilateral Trade Cooperation Support (“To what extent do you support your country signing a new trade agreement with the other country?”). The model specifications are in the Appendix section “Tables corresponding to results in Figure 4a and Figure 4b.”

In China, the strongest variation occurs in the reliability treatment group. It makes a difference if the other country is an ally (effect size approx. 1.7) or an adversary like the United States (approx. 1.1). Nonetheless, also here the identity of the trading partner becomes less important when confronted with unreliable past behaviour. When confronted with broken promises, respondents from both countries seem to care less about who the trading partner is, so that, on the whole, H1 cannot be rejected even when taking into account the identity of the other country, which has been found to be a remarkably robust predictor for trade cooperation support in previous research.Footnote 82 Again the responses to past behaviour treatments do not vary by the individual level of generalized trust, compare the Appendix.Footnote 83

With respect to the US-China trade war, these results suggest that the identity of the specific other country, that is China and the United States, respectively, matters the least when the trading partner has been unreliable. Across all treatments, support for bilateral trade cooperation diminishes when the other country has been unreliable. Amongst US respondents, the reaction to the identity of the trading partner in the control and reliable treatment groups indicates that China, the purple line, is perceived statistically significantly differently than an ally (in blue). To a large extent, the mirror image presents itself amongst Chinese respondents. Responses in the control and reliable scenarios suggest that the United States is viewed distinctly, especially compared to an ally. Interestingly, amongst both country samples, this difference is much less pronounced in the unreliable trade partner scenario. This suggests, even though the identity of the other country has incessantly been highlighted in the context of the US-China trade war, that US and Chinese respondents’ trade cooperation support would diminish when highlighting past unreliability, regardless if the other country is an US or Chinese adversary or ally. Thereby, while the response to reliable past trade behaviour varies across allies and adversaries, such as China and the United States, the response to unreliable past trade behaviour generalizes across different trading partners.

Conjoint

The United States and China interact across various issue realms. To the extent that mentioning broken trade promises severely shapes individuals’ cooperation support by affecting how trustworthy the other country is perceived, does this only apply to the realm of trade policy? Or are spillovers from other issue areas to trade cooperation support possible? To investigate this question, I conduct a choice-based conjoint asking for respondents’ preferred trade agreement.Footnote 84 As a brief reminder, in this conjoint, I vary past behaviour not just in trade but also in military affairs, human rights, environmental affairs, and culture.Footnote 85 Additionally, I vary the current level of bilateral trade, the projected level of economic growth due to the agreement, as well as the identity of the trading partner.

Figures 5a and 5b visualise the results from US and Chinese respondents, respectively. The point estimates in these graphs represent the mean outcome across all conjoint attribute levels, averaged across all other attributes.Footnote 88 As the choice is either 0 or 1, the mean is always 0.5 by design (ibid.). The results for the US support the evidence from the previous subsection. That is, unreliability in trade is punished and reliability is rewarded. The effect seems a little more symmetric for promise breaking in military affairs and human rights. However, promises in these areas, in contrast to environment and culture, have a statistically significant impact on respondents’ choice.Footnote 89 In contrast to the identity of the trading partner, the level of trade interaction and projected growth do not have a statistically significant effect.

Figure 5. Conjoint results indicating which proposal is preferred. Point estimates represent the mean outcome across all conjoint attribute levels, averaged across all other attributes.Footnote 86 Output generated with the cregg Package.Footnote 87

Responses amongst the US sample have the strongest reaction to discussions of past behaviour in the area of trade. The point estimate for unreliable trade behaviour lies at approximately 0.44 and for reliable trade behaviour at around 0.58. This strength of this effect is as anticipated as the outcome variable correspondingly elicits view of trade cooperation.

The reaction to past behaviour in the realm of military affairs is similar. The point estimate for unreliable behaviour corresponds to roughly 0.45 and for reliable behaviour 0.55. On the one hand, it is striking that behaviour in military politics affect trade cooperation support to such an extent. On the other hand, military affairs are traditionally considered “high politics” and relate to matters of security that are reemerging in importance in a new world shaped by power change and heightened polarization and nationalism. These findings support existing work highlighting the importance of economic and military affairs in public perception.Footnote 90

However, US and Chinese trade cooperation views are not just bidimensional. Reliability and unreliability in upholding promises in the realm of human rights have statistically significant effects on the trade response, with the former having a point estimate of around 0.45 and the latter with a point estimate of roughly 0.54. The effect sizes are therefore in a similar range as responses to the areas of trade and military affairs. Hence, US respondents’ trade views are considerable shaped by past behaviour in trade, military affairs, and human rights.

Interestingly, compared to trade, military, and human rights, the effects of past behaviour in environmental and cultural affairs are not statistically significant in shaping the support for trade cooperation. Similarly, the level of existing trade and growth prospects do not exhibit a statistically significant effect on the response. However, political relations with the trading partner are important, as bilateral trade with allies is supported more than with adversaries.

The responses from the Chinese sample support some of these patterns uncovered amongst US responses. First, mentioning unreliability or reliability in trade also has the largest effects on the response with statistically significant point estimates of approximately 0.38, and 0.63, respectively. These effects are even larger in magnitude than the response to the alliance with the other country.

Like in the US study, transgressions in military affairs and human rights have larger effect magnitudes on the response than environment and culture, although the latter two also have a statistically significant effect on the response. The point estimates for military affairs and human rights are nearly the same (for unreliability 0.45 and for reliability 0.56). Thus, Chinese respondents’ trade cooperation, like American survey takers, are also shaped by past behaviour in human rights. Given China's frequently discussed mixed record in upholding promises in human rights, this finding is striking.

The effects of the level of trade and environmental behaviour, although with statistically significant effects, are of much smaller magnitude. The effects of growth prospects, however, is not negligible in effect size with point estimates of 0.45 and 0.55. The importance of economic growth for a developing country like China may be more salient than in a developed country like the United States.

Despite this difference, like in the United States, the identity of trading partners has statistically significant effects on the choice, with point estimates at around 0.44 (adversary) and 0.48 (ally). While overall similar patterns prevail, more attributes have a statistically significant effect on the response in the Chinese sample. This suggests that Chinese citizens are more affected by past behaviour in other issue areas than US respondents, that is the degree of multidimensionality of trade cooperation support is even more pronounced amongst the Chinese sample than in the US sample.

The trade war between the United States and China is accordingly likely to be shaped by past behaviour not just in trade but also other issue areas. This trade war is likely to not be just about trade narrowly conceived but also about other realms of interaction. Thereby, the maintenance of public support for trade cooperation between the United States and China is more vulnerable. This suggests that trade cooperation views of individuals are clearly not unidimensional, as they are not solely affected by discussing past behaviour in trade directly. Rather, like Downs and JonesFootnote 91 and Powers and RenshonFootnote 92 convey, issue linkages and multidimensionality prevails. These findings therefore support H2. Within this setup, the results suggest that the interrelations of trade with military affairs and human rights are more pronounced than with environmental and cultural affairs. In this context, people seem to view the former group more as a matter of high, and the latter group more as a matter of low, politics. The justification for the trade war, as well as the confrontational policies between the United States and China, are therefore likely to be shaped by accusations pertaining not just to trade policy but also to other issue areas.

Conclusion

In the context of the US-China trade war, which Beijing has called the “biggest trade war in economic history,” the prevalence of promise-breaking accusations is striking. Accordingly, this article studies the importance of promise-breaking rhetoric for bilateral trade cooperation support amongst American and Chinese citizens. Overall, the results from the survey experiments in the United States and China suggest past trade behaviour shapes respondent's view on trade cooperation. While unreliability is punished and reliability rewarded, the ramifications of unreliability are more severe. In this context, the other country is perceived as less or more trustworthy depending on its past behaviour. As this is a more general tendency, unreliability in other nontrade issue areas is similarly damming for cooperation support. The conjoint findings suggest that trade cooperation is formed multidimensionally. Past behaviour in military affairs and human rights is particularly influential.

This research makes the following contributions to the existing literature and debates about the US-China trade war. First, on the level of individual trade cooperation in a context of trade wars, my studies shift the focus beyond individual-level attributes to important contextual factors regarding the rhetoric about the relation and interaction between trading partner countries. It is insufficient to limit the study of trade wars or conflict to merely material class wars.Footnote 93 Future research has to continue expanding beyond individual material perspectives and take into consideration other sources of individual trade cooperation attitudes, in this case trustworthiness concerns that arise with respect to the trading partner. As noted earlier in the article, economic and social-psychological explanations are not necessarily mutually exclusive in this context. By studying the trade war context, my findings contribute to a rapidly expanding IPE literature on the various determinants of economic attitudesFootnote 94 and how nonmaterial concerns have the potential to interact with economic concerns.Footnote 95

Second, my article reinforces the importance of political rhetoric surrounding trade policy in US-Chinese relations. What and how issues are emphasized has enormous importance in shaping public attitudes. Although different views on China's actual trade policy compliance prevail, the current consensus encompasses a negative view. Currently, not just China's trade compliance is discussed but also its compliance in other issue areas such as military affairs and human rights. As the asymmetries in the experimental findings show, it is easier to decrease trade cooperation support by highlighting noncompliant behaviour than increasing trade support by highlighting compliant behaviour. This suggests that employing the former rhetoric is more effective than the latter. As the lack of heterogeneous treatment effects according to common social demographics and generalised trust reveals, these principles resonate with a broad coalition amongst members of the mass public.

Thirdly and finally, this research hints at the potential for elites to leverage such trade policy rhetoric to mobilize support for confrontational foreign economic policies. The context of the trade interaction accordingly has the potential to shape views of the mass public. Such rhetoric has played an important role in the context of the US-China trade war. As a comparison between the survey experimental responses in the reliable and unreliable scenarios especially amongst US respondents shows, by appealing to fundamental norms of fairness and principles of trustworthiness, mass public views at least have the potential to be swayed toward supporting confrontational trade policies.

These findings in the context of the United States and China suggest more research is needed to understand in more detail the effect of emphasizing promise breaking in other issue areas beyond trade and how these interlinkages are used strategically by political elites. In this context, future research exploring the potential prevalence of such accusations in other past trade wars and examining the generalizability of these findings will be beneficial. Moreover, more research is needed to understand how material and nonmaterial concerns precisely affect each other in this regard. Exploring and disentangling the various causal mechanisms and ramifications of negative and positive rhetoric more generally in future research should yield important insights on how to improve or diminish prospects for cooperation between the United States and China, the world's two largest powers and trading nations.

How will US-China trade relations continue? Negative rhetoric is likely to grow as China's economic clout, relative to the United States’, expands. As the ongoing tensions reveal, the partial respite achieved by the Phase 1 trade deal has been short-lived. In a way, the aftermath of the Phase 1 deal has reinforced the perspective that China does not keep to its word in trade policy, as it did not buy the amount of US exports promised in the agreement.Footnote 96 The United States and China are increasingly engaged in a power transition situation, which is not just shaped by de facto economic and military power but perceptions over the intentions of the other power, that is coming developments in world order will not just be shaped by a power but also by a purpose, transition.Footnote 97 Political rhetoric seeking to diminish the trustworthiness of the other power by highlighting negative intentions, such as not keeping to one's word, are likely to rise as the change in the relative balance of power accelerates. Ultimately, for the US-China context, these malleable perceptions shaped by public discourse and rhetoric will decide over the potential for a peaceful or violent transition of power between the United States and China.

Appendix

Descriptive statistics

Table A1. Number of Respondents In Each Treatment Group

Table A2. Distribution of responses to outcome variable: “To what extent do you support your country signing a new trade agreement with the other country?”

Regressions

Table A3. Treatments and covariates for responses

Heterogeneous treatment effects

Figure A1. Heterogeneous treatment effects.

Please note that the calculations for gender in the United States encompass only three respondents that indicated “other.” Having the “other” response was not possible in China.

Measurement of generalized trust

Respondents were asked to rate the following items (sequence randomized) with a 7-point Likert scale (“Highly support”—“Highly oppose”). Items are from Miller and Mitamura.Footnote 98

• Most people tell a lie when it is for their benefit.

• Most people do not cooperate because they only pursue their own interests. Thus, things that could be done well through cooperation often fail because of these people.

• People devoted to unselfish causes are often exploited by others.

• Would you say that most of the time people are trying to be helpful or that they are mostly just looking out for themselves?

• Do you think most people would try to take advantage of you if they got a chance or would they try to be fair?

Tables corresponding to results in Figure 4a and Figure 4b

Table A4. Effects of Past Behaviour * Identity on Cooperation—US citizens

Table A5. Effects of Past Behavior * Identity on Cooperation—Chinese citizens

Causal mediation analysis

The main text discusses the trustworthiness variable as a manipulation check. I also conduct causal mediation analysis to assess whether and to what extent the responses are mediated by the degree of perceived trustworthiness. For this, I use the Mediate Package in RFootnote 99 to calculate the average causal mediation effects, direct and total effects based on the comparison between the “reliability” and “unreliability” groups.Footnote 100 These quantities, as well as sensitivity analyses, are displayed in the Appendix, compare Figures A3a and A3b.

Figure A2. Proportion mediated by trustworthiness in US and Chinese responses. Comparison between the treatment group “reliability” and “unreliability.”

By analysing the proportions mediated,Footnote 101 I find that trustworthiness mediates around 60 percent of the treatment effect amongst US citizens. Although lower for China, with only around 40 percent, the degree of trustworthiness perception appears as an important mediator. The effect of highlighting broken trade promises on trade cooperation support is mediated by how trustworthy the trading partner is perceived. In the case of broken trade promises, trustworthiness issues are more relevant than an individuals’ trust level per se (cf. heterogeneous treatment effects of generalized trust in the Appendix.)

These figures are based on the comparison between the experimental groups of “reliability” and “unreliability.”Footnote 102

Figure A3. Causal mediation analysis with “Keep” as the control value and “Break” as the treatment value. Output generated with the Mediate Package.Footnote 103

Figure A4. Sensitivity analysis of causal mediation analysis. Output generated with medsens Package.Footnote 104

Appendix B: Conjoint

Figure B1. Screenshot of respondent view of conjoint study in Qualtrics.