No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 December 2009

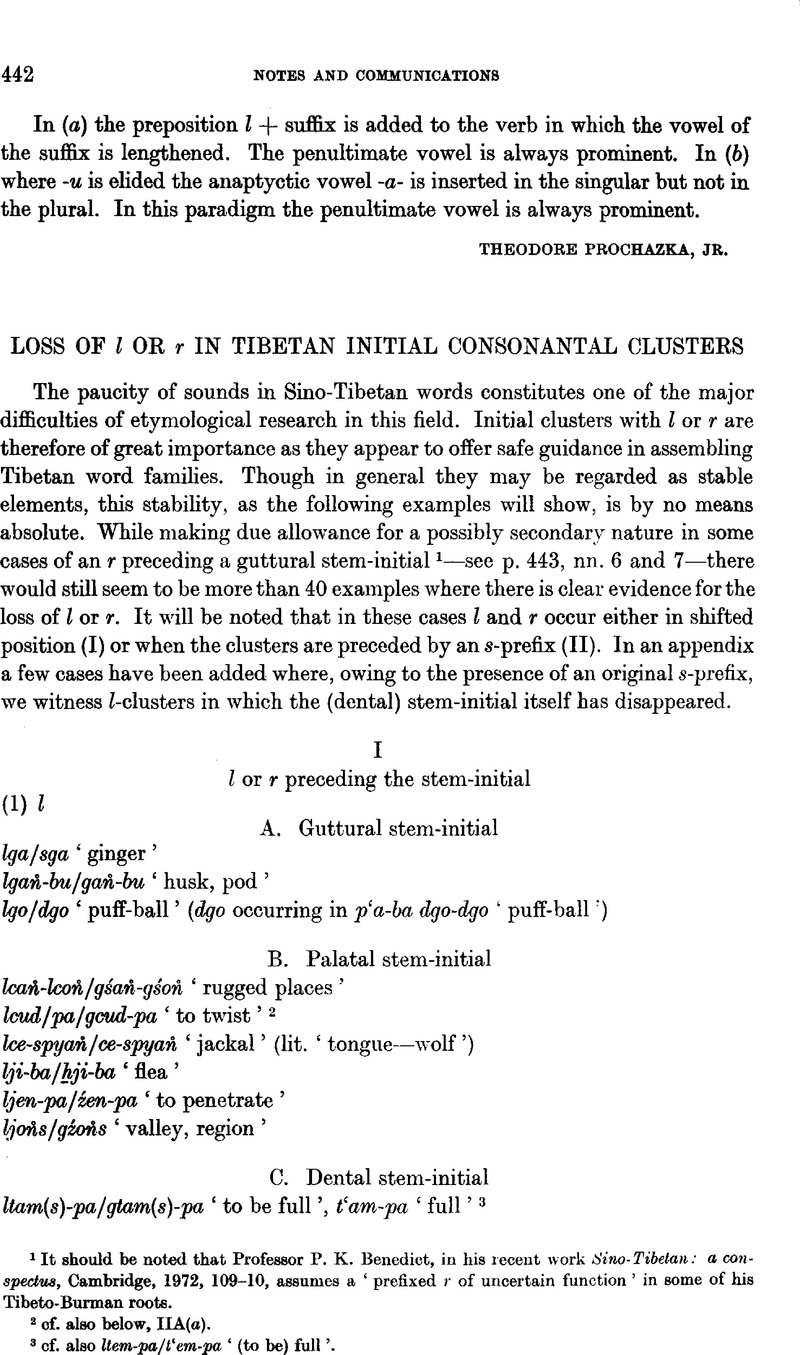

1 It should be noted that ProfessorBenedict, P. K., in his recent work Sino-Tibetan: a conspectus, Cambridge, 1972, 109–10CrossRefGoogle Scholar, assumes a ‘prefixed r of uncertain function’ in some of his Tibeto-Burman roots.

2 cf. also below, IIA(a).

3 cf. also Item-pa/t'em-pa ‘(to be) full’.

4 Also gdu-bu/gdub-bu/gdub. Cf. also zlum-po ‘round’ <*sdlum (see below Appendix, item 4). Idum ‘piece’ may belong to the same word family, then meaning originally a ‘round piece’.

5 See Mahāvyulpatti (ed. Sakaki), No. 5121.

6 r may be a secondary development when alternating with a d-prefix, but see n. 7.

7 cf. also brgad-pa ‘to smile’.

8 See ProfessorLi, F. K., ‘A Sino-Tibetan glossary from Tun-Huang’, T'oung Pao, XLIX, 4–5, 1961, p. 258, item 21Google Scholar.

9 See, however, under C(b) below and n. 11 of the article quoted in p. 444, n. 11 below.

10 Professor F. K. Li was the first to point out that t'a in t'a-skar belongs with rta. See his article ‘Certain phonetic influences of the Tibetan prefixes upon the root initial’, Academia Sinica, Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, IV, 2, 1933, 150Google Scholar.

11 This and the other examples under C(b) have been set out in more detail in ‘Ear, sharp, and hearing—a Tibetan word family’, in Boyce, M. and Gershevitch, I. (ed.), W. B. Henninq memorial volume, London, 1970, 406–8Google Scholar.

12 See Mahāvyutpatti (ed. Sakaki), No. 4005.

13 The verb skyu ![]() ba ‘to diminish’ (this meaning to be added to the entry in Jäschke's dictionary) seems to go back to an earlier *sknyu

ba ‘to diminish’ (this meaning to be added to the entry in Jäschke's dictionary) seems to go back to an earlier *sknyu ![]() -ba, belonging with cu

-ba, belonging with cu ![]() , c'u

, c'u ![]() , and nyu

, and nyu ![]() , ‘little’. A passage in the Vinayavibhanga, concerned with the monks going quietly from house to house (Narthang, , ẖDul, Nya 378Google Scholar = Tib. Tripitṭaka, XLIII, 233a2), which shows sgra bskyu

, ‘little’. A passage in the Vinayavibhanga, concerned with the monks going quietly from house to house (Narthang, , ẖDul, Nya 378Google Scholar = Tib. Tripitṭaka, XLIII, 233a2), which shows sgra bskyu ![]() followed by the synonymous ts'ig nyu

followed by the synonymous ts'ig nyu ![]() -

-![]() us, would appear to confirm this etymology. The Mahāvyutpatti (ed. Sakaki, No. 8537) renders alpaśabda by sgra skyu

us, would appear to confirm this etymology. The Mahāvyutpatti (ed. Sakaki, No. 8537) renders alpaśabda by sgra skyu ![]() -ba.

-ba.

14 Note, however, the retention of r in the palatalized variant rjen(-pa) of sgren(-mo) ‘naked’.

15 cf. also gśon ‘to put astride’ (wrongly doubted by Jäschke, , Dict., 566Google Scholar, and therefore left out by Das, , see, e.g., Tib. Tripiṭaka, XXXIX, 51c6–8Google Scholar) by the side of skyon-pa, and źon-pa ‘to mount’, which clearly belong with gyon-pa ‘to put on, wear’, the latter word being a derivative of gon-pa ‘idem’.

16 Note also the variant rmo-s ![]() gs of smre-s

gs of smre-s ![]() ags ‘to wail, lament’, listed by Schmidt and Jäschke, and the metathesis of the r, as in rgal ‘to cross’ ∼ sgral ‘to ferry across’ and rga ‘old’ ∼ dgre-ba ‘to grow old’ (see Asia Major, NS, I, 1, 1949, 12 ff.).

ags ‘to wail, lament’, listed by Schmidt and Jäschke, and the metathesis of the r, as in rgal ‘to cross’ ∼ sgral ‘to ferry across’ and rga ‘old’ ∼ dgre-ba ‘to grow old’ (see Asia Major, NS, I, 1, 1949, 12 ff.).

17 The entry smas-pa, taken over by Jäschke from I. J. Schmidt's Wörterbuch, can be confirmed in its verbal meaning by a passage from the Vinayavastu (Narthang, , ẖDul, Kha, 306B5Google Scholar = Tib. Trip., XLI, 178c8): lus dmas śi ![]() rma byu

rma byu ![]() -bas rnag ẖdzag la. Cf. also Divyāvadāna (ed. Cowell, and Neil, ), 4637Google Scholar. Note also sme-ba ‘spot, mark, mole’ by the side of rme-ba (and dme-ba) ‘idem’.

-bas rnag ẖdzag la. Cf. also Divyāvadāna (ed. Cowell, and Neil, ), 4637Google Scholar. Note also sme-ba ‘spot, mark, mole’ by the side of rme-ba (and dme-ba) ‘idem’.

18 The two verbs are clearly contrasted in th e translation of the well-known cliché (last two words) mukto mocaya tīrṇas tāraya āśvasta āśvāsaya parinirvṛtaḥ parinirvāpaya (Divyāvadāna, ed. Cowell, and Neil, , 3914–15Google Scholar): yo ![]() s-su mya-

s-su mya- ![]() an-las ma ẖdas-pa-rnams ni yo

an-las ma ẖdas-pa-rnams ni yo ![]() s-su mya-

s-su mya- ![]() an-las zlos-śig (Tib. Trip., XLI, 116d4–5).

an-las zlos-śig (Tib. Trip., XLI, 116d4–5).

19 For the loss of the l cf., e.g., ldag-pa/ẖdag-pa in I(1)C.

20 Both ẖdo-ba and zlo-ba are listed by Csoma and Schmidt. The example ma ẖdos-par ‘unspeakable’, rightly queried by Jäschke, who has referred to Schiefner's correction ma ẖos-par (see now Tib. Trip., XL, 107a5), has been taken over by Das, (Diet., 689)Google Scholar without question mark and without reference to either Jäschke or Schiefner.

21 cf. also the doublet slog.

22 See also above, p. 443, n. 4.