The transition to post-industrial economies has triggered important social and political transformations that have taken place simultaneously over the past decades. Numerous studies have addressed how major socio-economic transformations like globalization, the expansion of the welfare state, educational upgrading and the tertiarization of the occupational structure have fundamentally altered the configuration of cleavage politics in West European democracies (see, for example, Beramendi et al. Reference Benedetto, Hix and Mastrorocco2015; Kriesi et al. Reference Kohler and Zuckerman2012). While considerable effort has been placed on explaining new patterns of class voting in post-industrial societies (Gingrich and Häusermann Reference Gelman and Imbens2015; Houtman, Achterberg and Derks Reference Häusermann2008; Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018), recent studies have ignored the idea that the industrial class structure might have left an imprint on contemporary patterns of class voting.

While individuals' class location has been frequently associated with party support, less attention has been placed on the impact of parental class. Existing analyses of the political preferences of typical post-industrial classes, like sociocultural professionals (SCPs), tend to ignore the fact that these individuals have often been socialized in a different parental class of origin. The fast pace of the tertiarization of the occupational structure and the expansion of education imply that in a post-industrial context, we observe specific patterns of intergenerational mobility in which growing post-industrial classes have been socialized in a different – industrial – parental class. Therefore, it is surprising that the literature on post-industrial class voting has not yet studied the relevance of parental class of origin for new class–party alignments, especially as several studies have documented the impact of social mobility on political preferences (De Graaf, Nieuwbeerta and Heath Reference Dalton1995; Kohler Reference Knutsen and Langsæther2005; Nieuwbeerta, De Graaf and Ultee Reference Mortimer and Lorence2000; Turner 1992). Moreover, recent trends of post-industrial realignment in the political preferences of different social classes mean that intergenerational social mobility has taken place in a context in which the social classes between which individuals move have also shifted their partisan allegiances. We therefore connect literature on class voting and realignment with that of political socialization in the class of origin, which demonstrates a lasting impact on political preferences and behaviour (Dalton Reference Curtis1982; Glass, Bengtson and Dunham Reference Gingrich and Häusermann1986).

This article investigates how class of origin (parental class) and specific patterns of intergenerational social mobility impact left-wing party support among new and old core left-wing constituencies in the context of post-industrial occupational transformation and electoral realignment. We focus on the electorates of left-wing parties, as they form the party bloc most affected by post-industrial realignment, partially because their traditional class constituencies experienced greater numerical variation due to occupational change. We expect that early political socialization in classes of core left-wing electorates has a lasting impact due to the intergenerational transmission of partisan leaning and (subjective) class identity. Given the strong link between the working class and the Left in the industrial context, we would expect that part of this allegiance should, through early socialization, be passed on to the offspring generation – even if they move to a different class location. We hypothesize that this pattern of intergenerational transmission grounds part of the new post-industrial alignment of middle-class support for the Left. For younger generations, this industrial legacy should become weaker, reflecting patterns of post-industrial realignment.

We test our expectations using British, German and Swiss household panel data for several generations of respondents – with different (early socialization) contexts at various stages of realignment. In doing so, this article makes two main contributions. First, we demonstrate that class of origin predicts differences in party preferences, irrespectively from own class location. Depending on the context of class–party alignments, it matters differently: socialization in the production working class is more associated with left-wing support in older generations, while we observe some reverse patterns for SCPs. Second, when analysing specific intergenerational class transitions, we show how part of the contemporary middle-class left-wing support is a remaining legacy of industrial class–party alignments. For younger generations who move to the middle class, however, the legacy of production working-class origins is weaker. At the same time, we do not observe a strong lasting impact of SCP socialization for younger generations of respondents who move to a different (middle-class) location. Some of these results differ by country, as they represent different stages of realignment.

The implications of these findings are that exclusively considering respondents' current class, while ignoring class of origin, leads to an overestimation of the level of post-industrial electoral realignment. Even in post-industrial economies, we thus find a legacy of the old industrial political conflict that is still present in current patterns of party preferences through socialization in class of origin. Even if production workers are in numerical decline, their electoral relevance persists through this lasting impact of growing up in a specific (industrial) class. However, this means that for younger generations, socialization into these traditional class–party alignments continues to be weaker. As the legacy of post-industrial classes (such as SCPs) is not equally lasting after individuals move to a different class location and, in some cases, seems to benefit other parties like the Greens, this could promote higher levels of volatility among these groups in the absence of lasting socialization experiences in the class of origin.

Theory

In post-industrial societies, we find a greater diversity of occupations, most of which did not exist during the industrial era. Consequently, many individuals in typically post-industrial occupations hold a different class location than the parental class of origin in which they were socialized. The transition to post-industrial economies has had profound implications for the occupational structure due to increased access to education, the decline of the manufacturing sector since the 1970s and the expansion of the service sector. As a result, low-skilled and unskilled industrial jobs have declined, while low-skilled service jobs and (semi-)professional jobs in the service sector have increased (Fernández-Macías Reference Evans and Tilley2012; Oesch Reference Oesch2013). Post-industrialization has therefore led to specific patterns of intergenerational social mobility between typical industrial and post-industrial occupational classes. For instance, while the proportion of production workers has declined over recent decades, the parents of many individuals currently in professional occupations were part of the manufacturing working class. In the post-industrial occupational structure, it is important to distinguish occupational classes not only vertically (hierarchical position in the employment structure), but also horizontally by work logic (the sector or nature of the work) (Oesch Reference Oesch2006). Intergenerational social mobility at a time of post-industrial transformation can thus imply not only vertical, but also horizontal, mobility. In comparison to their parents, individuals can move up on the social ladder (for example, professionals with working-class roots) and/or work in a different sector (for example, service workers with origins in the production working class).

Previous studies concerning the political implications of intergenerational social mobility have often concluded that the political preferences of socially mobile citizens are found somewhere between the class of origin and the class of destination (Knutsen Reference Kitschelt and Rehm2006). In fact, social mobility is associated with lower parent–offspring political resemblance (Van Ditmars Reference Van der Waal, Achterberg and Houtman2020). The change in class location leads to a certain level of adaption of political preferences to those in the destination class, according to the ‘acculturation hypothesis’ (De Graaf, Nieuwbeerta and Heath Reference Dalton1995). Acculturation is grounded on the argument that one's class position moulds political preferences. The attitudinal shift can result from the change in social status/economic circumstances associated with class mobility (Evans Reference De Graaf, Nieuwbeerta and Heath1993; O'Grady Reference Nieuwbeerta, De Graaf and Ultee2019), or from occupational experiences that shape values and behaviours within and beyond the work sphere (Ares Reference Ares2020; Kitschelt and Rehm Reference Houtman, Achterberg and Derks2014; Mortimer and Lorence Reference Mood1979). Re-socialization in the class of destination also takes place through social interactions with peers and embedment in social networks (Goldthorpe Reference Goldberg and Sciarini1986; Lindh, Andersson and Volker Reference Langsæther, Evans and O'Grady2021).

On the other hand, studies also report a lasting influence of class of origin (Turner 1992) due to enduring processes of social learning and (political) socialization during the impressionable years. The intergenerational transmission of political preferences and identification (Dalton Reference Curtis1982; Glass, Bengtson and Dunham Reference Gingrich and Häusermann1986; Van Ditmars Reference Van Ditmars2022), and of a ‘sticky’ subjective class identity (for example, a continued identification with the working class) (Curtis Reference Bornschier, Kriesi and Rydgren2016; Langsæther, Evans and O'Grady Reference Kriesi2022), can therefore explain a remaining influence of class of origin on socially mobile individuals' political preferences. Early socialization in a specific class of origin can continue to exert an influence later, even when an individual moves to a different (post-industrial) class location. This is particularly the case for those with roots in milieus with strong industrial class–party alignments, such as the blue-collar working class. While the class cleavage has formed the most important political divide for most of the 20th century, increased levels of volatility since the 1970s have sparked scholarly discussion about the decline of cleavages and the continued significance of class voting (Bartolini and Mair Reference Arzheimer and Rydgren1990). While class–party alliances have shifted, partly due to new party competition from the Radical Right and the increased importance of new (sociocultural) issues (Evans Reference Evans2000; Evans Reference Evans2017; Knutsen Reference Kitschelt and Rehm2006), this does not mean that social class has become unimportant as a context of political socialization and a determinant of life chances (Goldthorpe Reference Goldthorpe2002; Van der Waal, Achterberg and Houtman 2007). However, due to transformations in class voting, the enduring impact, as well as the political implications, of early socialization in a working-class environment is likely not equal across different generations.

The rise of new post-industrial patterns of social mobility have taken place at a time in which the electoral alignment between social classes and party families has also shifted. Therefore, the kind of partisan allegiances in which individuals have been socialized in their class of origin depend on the stage of realignment during that period. The typically industrial opposition between a left-wing working class and a right-wing middle class does not provide a good depiction of class voting today. Due to the rise of the Radical Right and the increasing salience of cultural conflict, post-industrial class–party alignments are characterized by left-wing party support that comes decreasingly from (manufacturing) workers (Arzheimer Reference Ares and Van Ditmars2013; Oesch Reference Oesch2008a; Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018) and increasingly from professionals in sociocultural occupations (Gingrich and Häusermann Reference Gelman and Imbens2015; Güveli Reference Goldthorpe2006). While manufacturing workers constituted the core electorate of the Left during the trente glorieuses, over the past few decades, their left-wing alignment decreased in favour of the Radical Right or abstention (Bornschier and Kriesi Reference Beramendi2013; Evans and Tilley Reference Evans2017; Oesch Reference Oesch2008a), leading to the production working class recently becoming a contested stronghold between left-wing and radical right-wing parties (Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018). The decline in the left-wing working-class vote has often been compensated by rising support among professionals, specifically SCPs – a growing class in the transition to post-industrial economies that tends to hold liberal policy preferences (Gingrich and Häusermann Reference Gelman and Imbens2015; Güveli Reference Goldthorpe2006; Häusermann et al. Reference Häusermann, Kriesi and Beramendi2022). Therefore, the increasing middle-class profile of left-wing parties has drawn specifically from this occupational class (Abou-Chadi and Hix Reference Abou-Chadi and Hix2021), which has become the new electoral preserve of the Left. On the other hand, large employers, managers and professionals in technical occupations (the ‘old’ middle class) still constitute the electoral preserve of mainstream right-wing parties – very much in line with industrial class–party alignments (Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018).

In light of the changes in class–party alignments, together with new combinations of class of origin and destination, we ask: what are the political consequences of intergenerational social mobility in contexts of post-industrial realignment in which the core class constituencies of different parties – especially on the Left – are shifting? Even though previous work has investigated the political consequences of social mobility (De Graaf, Nieuwbeerta and Heath Reference Dalton1995; Nieuwbeerta, De Graaf and Ultee Reference Mortimer and Lorence2000; Turner 1992),Footnote 1 they have assumed rather static political alignments across classes of origin and destination. On the other hand, the literature on post-industrial class voting (Gingrich and Häusermann Reference Gelman and Imbens2015; Häusermann and Kriesi Reference Güveli2015; Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018) has exclusively focused on individuals' own social class location. This has possibly led to overestimating the pace at which occupational transformations have affected electoral alignments. Given the relevance of early political socialization, neglecting parental class of origin could be underestimating the remaining legacy of the industrial class conflict among older generations. Socialization in traditional industrial left-wing classes of origin is likely behind part of the contemporary middle-class support for the Left. Even if manufacturing occupations are in numerical decline, their offspring are part of current constituencies. Therefore, we argue that it is crucial to bring parental class of origin into the equation.

Our article focuses on support for the Left for two main reasons. First, class voting for left-wing parties has frequently been addressed in both industrial and post-industrial contexts, which has led to accumulated evidence regarding which social classes constitute the core electorates of the Left in the past and the present. Secondly, and most importantly, these social classes exemplify the largest post-industrial changes to the social structure, which is one of the reasons why the left-wing party bloc has been most affected by post-industrial realignment (Benedetto, Hix and Mastrorocco Reference Bartolini and Mair2020). Hence, new patterns of intergenerational mobility in post-industrial societies intrinsically concern the core electorates of the Left. We expect that some of the contemporary class–party alignments are partially a legacy of the industrial past, as some patterns of ‘realignment’ are capitalizing on the industrial class background of the new middle class, specifically SCPs. We formulate this expectation in a few testable hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a: Socialization in the production working class is expected to explain differences in contemporary patterns of left-wing party support, independently from current own class location.

Hypothesis 1b: However, we expect the impact of different classes of origin on left-wing party support to differ across contexts due to changed patterns of class–party realignment over time.

We approximate contexts of realignment by studying different countries and generations. The stages of alignment range from a pure industrial alignment in which workers constitute the core left-wing electorate, to a realigned scenario in which SCPs represent the Left's main electoral preserve. While the production working class clearly constituted an environment for left-wing socialization until the 1970s, this is less likely to be the case in most West European democracies in the 2000s. Therefore, among the baby boomers (born 1946–64), who lived through the largest post-industrial transformation and experienced early political socialization in an industrially aligned context, those with a production working-class family background are expected to show higher support for left-wing parties than those with different classes of origin. This same class background, however, should not be associated with higher left-wing party support for younger generations of respondents socialized during more recent stages of class–party realignments. Correspondingly, offspring of SCPs socialized during later stages of realignment are expected to show higher left-wing support. This implies that the imprint of industrial class alignments acting through the intergenerational transmission of preferences and class identification weakens as classes and parties realign. Moreover, as we elaborate later, party systems differ in the extent of realignment. In some countries, SCP support for the Left is a more recent phenomenon than in others.

Secondly, bringing in the combination of class of origin and class of destination, we expect:

Hypothesis 2a: Intergenerational mobility between social classes that constitute old and new left-wing constituencies fosters particularly high levels of left-wing party support.

This means that individuals with a working-class background who move into the SCP class should show higher levels of left-wing support in comparison to others with the same class of origin. Interestingly, this expectation goes against some suggestions from traditional studies on intergenerational mobility, proposing that upward social mobility would be conducive to lower left-wing/higher right-wing support. Again, we qualify our expectation by hypothesizing:

Hypothesis 2b: Specific patterns of social (im)mobility are differently related to left-wing party support across contexts and generations.

Across countries with differing trajectories of post-industrial class–party realignment, different generations have experienced different stages of (re)alignment in class of origin and destination, which is expected to be reflected in patterns of left-wing support across different social mobility transitions. These differences should be especially visible for transitions into and out of old and new left-wing electorates. Moreover, certain transitions (for example, out of the production working class) are becoming less common among younger generations. This highlights the importance of studying specific class transitions to understand whether legacies of industrial alignments are still observable today and which effects of parental class of origin are observed in younger generations that are socialized in realigned party systems.

Left-Wing Party Support in the UK, Germany and Switzerland

In order to address how the lasting impact of socialization in class of origin operates under post-industrial realignment, we study three countries that differ in the stage thereof: the UK, Germany and Switzerland. While these countries currently share a post-industrial class structure and a relatively stable presence of social-democratic and other (newer) left-wing parties, they differ in the pace at which they have experienced post-industrial electoral realignment. Switzerland constitutes a paradigmatic case of early realignment, with one of the most successful populist right-wing parties in Europe, the Swiss People's Party (SVP), mobilizing large support from manufacturing workers (Oesch Reference Oesch2008a) while sticking to the populist ‘winning formula’ (Lorenzini and Van Ditmars Reference Lindh, Andersson and Volker2019). At the same time, the Social Democratic Party of Switzerland has also drawn over-proportionally from SCPs, becoming an example of successful middle-class mobilization (Goldberg and Sciarini Reference Goerres, Spies and Kumlin2014).

By comparison, post-industrial realignment has taken place at a slower pace in Germany and the UK. In these two countries, the surge in support for a populist right-wing alternative among workers is rather recent and the traditional economic cleavage appears to still be strong, grounding workers' support for the Left (Oesch Reference Oesch2008b). More recently, the populist right-wing Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) has gained support in Germany. While initially no higher support was found among blue-collar workers (Goerres, Spies and Kumlin Reference Glass, Bengtson and Dunham2018), in some states, the working class showed even higher AfD than Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) support in the 2017 elections (Adorf Reference Adorf2018). In the UK, the working class appears not so much realigned, but rather dealigned from Labour, in favour of abstention (Evans and Tilley Reference Evans2017). While the United Kingdom Independent Party (UKIP) catered to some of these voters, this party is strongly disadvantaged by the electoral system.

Left-wing parties in Germany and the UK have also increasingly drawn from an SCP electoral basis (Evans and Tilley Reference Evans2017; Gingrich and Häusermann Reference Gelman and Imbens2015). However, the divergence between the two party systems could lead to differences in how successful the Left is in mobilizing middle-class voters. While in the UK, Labour fulfils this role; in Germany, part of the SCP electorate is contested by the Greens. Due to the two-party system and the smaller success of parties competing on cultural issues, we expect the UK to be more ‘industrially aligned’ than Germany, where the early success of New Left parties and the (more recent) surge in populist right-wing support could be advancing realignment.

Rooted in these differences across countries over time, we expect that the legacy of the industrial class conflict is overall more prominently observable in the UK, followed by Germany and much less so in Switzerland. We further address stages of realignment by studying different generations within countries. This means that especially for older generations in the UK and Germany, we expect socialization in class of origin to leave an imprint on partisan preferences following an industrial logic. The earlier the process of realignment started, the more we can expect realigned patterns of class–party allegiance to be already observable through socialization in the class of origin. This means that while in Germany and the UK, we only expect to observe signs of a realigned logic among younger generations, in Switzerland, this might also manifest among older generations.

Research Design

Data

Addressing the questions at hand requires detailed information from recent years on individuals' occupation, parental occupation when they were young (14/15 years old) and party preferences. Moreover, studying intergenerational transitions between specific classes by generation imposes high demands on the number of observations required. The three countries under study offer the largest household panel studies of Europe, which meet these data requirements. We employ: the UK Household Longitudinal Study (UKHLS), harmonized with the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) (University of Essex et al. Reference Turner2020); the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (G-SOEP) (SOEP 2019); and the Swiss Household Panel (SHP) (SHP Group Reference O'Grady2021). The analytic samples comprise, respectively, all British, German and Swiss citizens over 17 years old (eligible to vote), who were at the time of the survey years employed and not enrolled in full-time education.

Variables

The dependent variable in our analyses is support for left-wing parties.Footnote 2 In the BHPS/UKHLS, this implies a party preference for, or identification with, the Labour Party or other left-wing parties.Footnote 3 In the G-SOEP, party identification with the social-democratic SPD or the socialist party Die Linke is used. In the SHP, we operationalize this with a party preference for the Social Democratic Party of Switzerland or the communist Swiss Party of Labour. The reference category includes support for, or identification with, other parties, no party and those who would not vote. We do not include green parties as part of the Left. Even if some green parties can be placed ideologically on the Left, the social composition of their electorates has not been affected by post-industrialization, as they have drawn from a typically post-industrial class – SCPs – from the beginning and do not have a core class electorate in the industrial alignment.

For the operationalization of class location for parental class of originFootnote 4 and respondents' own class, we use a simplified version of Oesch's (Reference Oesch2006) eight-class scheme, as presented in Table 1. Intergenerational social mobility implies having a different class location than one's parents. For our analysis, we create a categorical variable of specific intergenerational class transitions of interest, that is, combinations of parental class of origin and respondents' class of destination. This variable is created for each observation and is thus not necessarily stable over respondents’ observed person-years. Since our interest is in new and old core constituencies of the Left, we mainly focus on transitions out of the production working class and into the SCP. For younger generations, we also consider the SCP as a relevant class of origin. As a point of comparison, we report transitions from and into the ‘old middle class’ (OMC), which we operationalize by aggregating managers, technical professionals, self-employed professionals and large business owners.Footnote 5 This group provides an optimal category of comparison since it has remained a stable electoral preserve of mainstream right-wing parties (Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018). The shaded cells in Table 1 indicate the five (aggregated) class categories used in the analyses.

Table 1. Simplified Oesch (2006) eight-class scheme, with representative professions

Note: Shaded cells indicate authors' categories of (aggregated) classes used in the analyses.

The analyses distinguish three generations of respondents: baby boomers (1946–64); Gen X (1965–80); and millennials (1981–96). While the baby boomers have been socialized during periods of industrial alignments, the two younger generations have been socialized during periods of increasing post-industrial realignment. Control variables are included for part- or full-time employment, gender, age, and marital status.Footnote 6

Analyses

We compare left-wing party support across respondents, with a specific focus on those who have either been socialized in a left-wing core constituency class or currently find themselves in one of these class locations. The main analyses rely on observations from 2008 to 2018/19,Footnote 7 as the focus of the study is on explaining contemporary patterns of class–party links under post-industrial realignment. We therefore observe these patterns from the Euro crisis until most recently. Narrowing the time window allows us to establish that we are focusing on a period of realigned politics (while observing different stages through country and generation comparisons) and to reduce some of the contextual variation. If we relied on all time points available for the three datasets, we would be drawing on different time frames for each of the countries. Hence, we limit the analyses to this period to improve comparability and fit with our theoretical propositions.

Our analyses rely on two sets of estimations. All of them are linear probability models (LPMs) (Angrist and Pischke Reference Angrist and Pischke2008), with party preference (1 = left-wing party; 0 = other/no party) as the dependent variable. We opt for LPMs instead of non-linear models because of the possibility of comparing coefficients across models and the easier interpretation, and because the results of interest for our purposes are the average marginal effects, for which the application of an LPM instead of a logit model is appropriate (Mood Reference Lorenzini, Van Ditmars, Hutter and Kriesi2010). In the first analyses (testing H1), we relate respondents' class and their parental class of origin to left-wing support. To address differences by generation – and to test expectations about stages of realignment – we model interactions between parental class of origin and generation. In the second part of the analyses (testing H2), we first investigate how specific intergenerational class transitions of interest predict left-wing support, using the immobile OMC as a reference category. We then further specify interactions between these transitions and respondents' generation.

We estimate random-effect (RE) panel models estimated by generalized least squares, using for each respondent all waves available from the year range 2008–18/19.Footnote 8 We rely on this modelling approach because our key independent variable of interest – parental class of origin – is time-invariant. Estimation strategies relying exclusively on within-individual variation are unsuitable for addressing the impact of parental class of origin. The RE modelling approach gives an adequate indication of left-wing party support per respondent given their socialization background (in the class of origin) and their class of destination, as it combines all information available for each respondent, using the richness of the longitudinal data at hand. By maximizing the information available for each respondent from the panel, the models smoothen out potential ‘noise’ within each respondent due to specific time/election effects.

An RE model for several periods follows the following formula (for the first analyses not differentiating between generations):

$$\eqalign{{\rm VoteLef}{\rm t}_{{\rm it}} = &\beta _1{\rm RespClas}{\rm s}_{{\rm it}} + \gamma _1{\rm ParentalClas}{\rm s}_i + \beta _2{\rm Ag}{\rm e}_{{\rm it}} \cr & \quad + \beta _3{\rm Parttim}{\rm e}_{{\rm it}} + \beta _4{\rm CivilStatu}{\rm s}_{it} + \gamma _2{\rm Gende}{\rm r}_i + \theta _i + \varepsilon _{it}, \;} $$

$$\eqalign{{\rm VoteLef}{\rm t}_{{\rm it}} = &\beta _1{\rm RespClas}{\rm s}_{{\rm it}} + \gamma _1{\rm ParentalClas}{\rm s}_i + \beta _2{\rm Ag}{\rm e}_{{\rm it}} \cr & \quad + \beta _3{\rm Parttim}{\rm e}_{{\rm it}} + \beta _4{\rm CivilStatu}{\rm s}_{it} + \gamma _2{\rm Gende}{\rm r}_i + \theta _i + \varepsilon _{it}, \;} $$where i = 1, … , N refers to individuals and t = 1, …, T to time periods. Explanatory variables are of two types: wk it (k = 1, …, K) – with βk coefficients – vary over time and within units (respondents' class location, part-/full-time work, civil status and age); and zji (j = 1, …, J) – with γj coefficients – vary only between units because they are time-invariant unit characteristics (parental class of origin and gender). This model includes a term, θi, for unit effects and a disturbance, εit, that varies over time and units. The analyses by generation follow the same model but include an interaction between parental class of origin and generation. The second set of analyses, focusing on transitions, omit the variables corresponding to class of origin and destination and include instead a categorical variable identifying different combinations of origin and destination.

Results

Patterns of Intergenerational Social Mobility in Post-industrial Societies

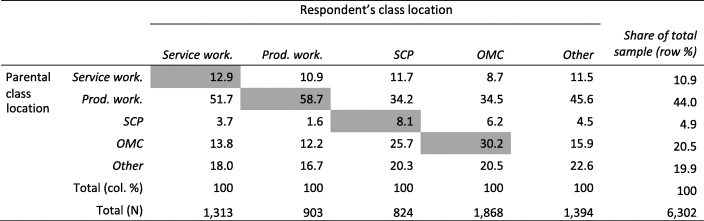

Tables 2 to 4 present descriptive statistics for combinations of class of origin and class of destination, showcasing the importance of addressing intergenerational mobility demonstrated by the strong presence of industrial occupations in parental class of origin. In the UK and Germany, over 40 per cent of all respondents have their roots in the production working class, against roughly 30 per cent in Switzerland. Focusing on the left-wing core constituency classes, we observe several common patterns of intergenerational stability and mobility. First, production workers show the highest level of class reproduction: in Germany and the UK, around 60 per cent; in Switzerland, close to 40 per cent. Secondly, many respondents with a production working-class background have moved to different classes. Many service workers have a production working-class background, while the same goes for large shares of the SCP (about one-third in the UK and Germany, and 22 per cent in Switzerland), and similar figures are observed for the OMC. These two latter types of upward social mobility are the most common, following patterns of occupational upgrading. Interestingly, one of these transitions is into a new core left-wing electorate (the SCP), while the other is not (the OMC). Less common types of mobility out of left-wing constituencies concern individuals with service worker or SCP origins who move to different classes (each close to 10 per cent or lower in all three countries), which reflects the recent nature of these occupational transformations.

Table 2. UK: parental class location by respondents’ class location, column percentages

Note: N = 6,302. Cells indicate for each class of destination (columns) the percentage of respondents with the respective parental class location (rows). Shaded cells indicate social immobility; off-diagonal cells indicate social mobility.

SCP = socio-cultural professionals. OMC = old middle class.

Source: Authors' calculation using BHPS/UKHLS 2008–19 data.

Overall, the patterns of intergenerational mobility of interest here are relatively similar across the three countries. The discrepancies in absolute numbers mostly come from differences in the size of the production working class in parental origin, which is larger in the UK and Germany than in Switzerland. Of greatest relevance is the fact that transitions (or stability) between social classes that represent left-wing core constituencies are numerous in the three samples under consideration.

Class of Origin and Left-Wing Party Support

To test H1a, Figure 1 displays average marginal effects of left-wing party support by class of origin and class of destination, in comparison with the OMC. In line with our expectation, the results suggest that – net of respondents' own class – parental class of origin predicts significant differences in left-wing support. In the UK and Germany, we find clear evidence of the legacy of roots in the production working class (H1a): having a working-class background increases the probability of voting for the Left by over 5 percentage points (compared to having an OMC background). In Switzerland, such earlier industrial alignment is not observable: only the offspring of the SCP – but not of production workers – are more likely to vote for the Left than OMC offspring. Overall, the results indicate that parental class of origin is strongly related to party leaning to a similar or even larger extent than respondents' own class.

Fig. 1. Impact of parental and respondents’ class (net of each other) on left-wing party support.

Note: Average marginal effects (with 95 per cent confidence intervals) on probability to support a left-wing party, relative to the reference category of the old middle class. Estimations based on random effect regression models in Table S1 in the Online Supplementary Material. Controls: full-/part-time work, civil status, gender and age (Germany = East/West Germany in 1989). Data are from BHPS/UKHLS 2008–19 (N = 6,301), G-SOEP 2008–18 (N = 13,167) and SHP 2008–19 (N = 6,157).

The differences in results across the three countries show that the impact of the class of origin depends on the context of realignment (H1b). Switzerland constitutes one of the early examples of realignment, which manifests in the association between parental class and left-wing support that resembles the post-industrial pattern of alignment found by respondents' class and does not reflect the industrial alignment between production workers and the Left. In this realigned context, offspring of the SCP and SCPs themselves are more likely to vote for the Left than the OMC offspring. In the UK, we find a similar left-wing legacy of being socialized in an SCP parental class, but not in Germany, which goes partly against our expectation of Germany representing a more realigned case than the UK. However, these results can be explained by the high support for the Greens by German SCPs (see Figure S1 in the Online Supplementary Material). This trend among SCP offspring in the UK could be a consequence of Labour's attempts to mobilize the middle classes in the 1990s (Evans and Tilley Reference Evans2017). Interestingly, in the UK, a working-class family background is related to higher support for the Left, but this relationship is not evident for respondents' class (when controlling for parental class). This, again, could indicate that the UK is at a later stage of realignment than we anticipated. In fact, replicating the analyses for the 1990s and early 2000s (see Figure S2 in the Online Supplementary Material) indicates a strong alignment between production workers and the Left, both in the UK and in Germany, but not in early-realigned Switzerland.

The comparison of the three countries indicates that the legacy of class of origin is related to the stage of post-industrial electoral realignment. We further address this by disaggregating the analyses by respondents' generation (baby boomers, Gen X and millennials),Footnote 9 as presented in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. Impact of parental class (net of respondents’ class) on left-wing party support by generation

Note: Average marginal effects (with 95 per cent confidence intervals) on probability to support a left-wing party, relative to the reference category of the old middle class. Estimations based on random effect regression models in Table S2 in the Online Supplementary Material. Controls: full-/part-time work, civil status, gender and age (Germany = East/West Germany in 1989). Data are from BHPS/UKHLS 2008–19 (N = 5,967), G-SOEP 2008–18 (N = 12,957) and SHP 2008–19 (N = 5,952).

The patterns regarding the relation between parental class and party support across generations are overall in line with our expectations. In the UK and Germany, baby boomers socialized in a production working class compared to in the OMC are more likely to support left-wing parties (a difference of about 0.10 in both countries), but this association fades across generations and becomes statistically insignificant for millennials. We find a similar pattern, though in the opposite direction, for SCP offspring in Switzerland and the UK. Here, the coefficients for having an SCP background (compared to OMC) indicate this more recent post-industrial legacy: while for baby boomers, this is not related to higher left-wing support, it is for Gen X and millennials. For some classes, we do not find such clear trends across countries. While we might have expected service workers to be increasingly more important left-wing socialization milieus in younger generations, there is no clear evidence in this direction. In Switzerland, even among baby boomers, socialization in the production working class is not linked to higher left-wing support, indicating that this class has not been a core electorate of the Left for a long time. Again, against our expectation, there is no left-wing imprint among younger offspring generations of the SCP in Germany. When again incorporating the Greens as part of the Left (as presented in Figure S3 in the Online Supplementary Material), socialization in the SCP class is associated with higher support for left-wing/green parties among Gen X and millennials.

Overall, the comparisons by country and generation indicate that parental class of origin is a relevant predictor of political preferences.Footnote 10 However, the lasting nature of socialization in the class of origin depends on the party–class alignments prevalent in the context at the time. We thus find support for our expectations formulated in H1a and H1b. The results from Figure 2 also indicate that some generational transformations were masked in the analyses that pooled them together.

Intergenerational Class Transitions and Left-Wing Party Support

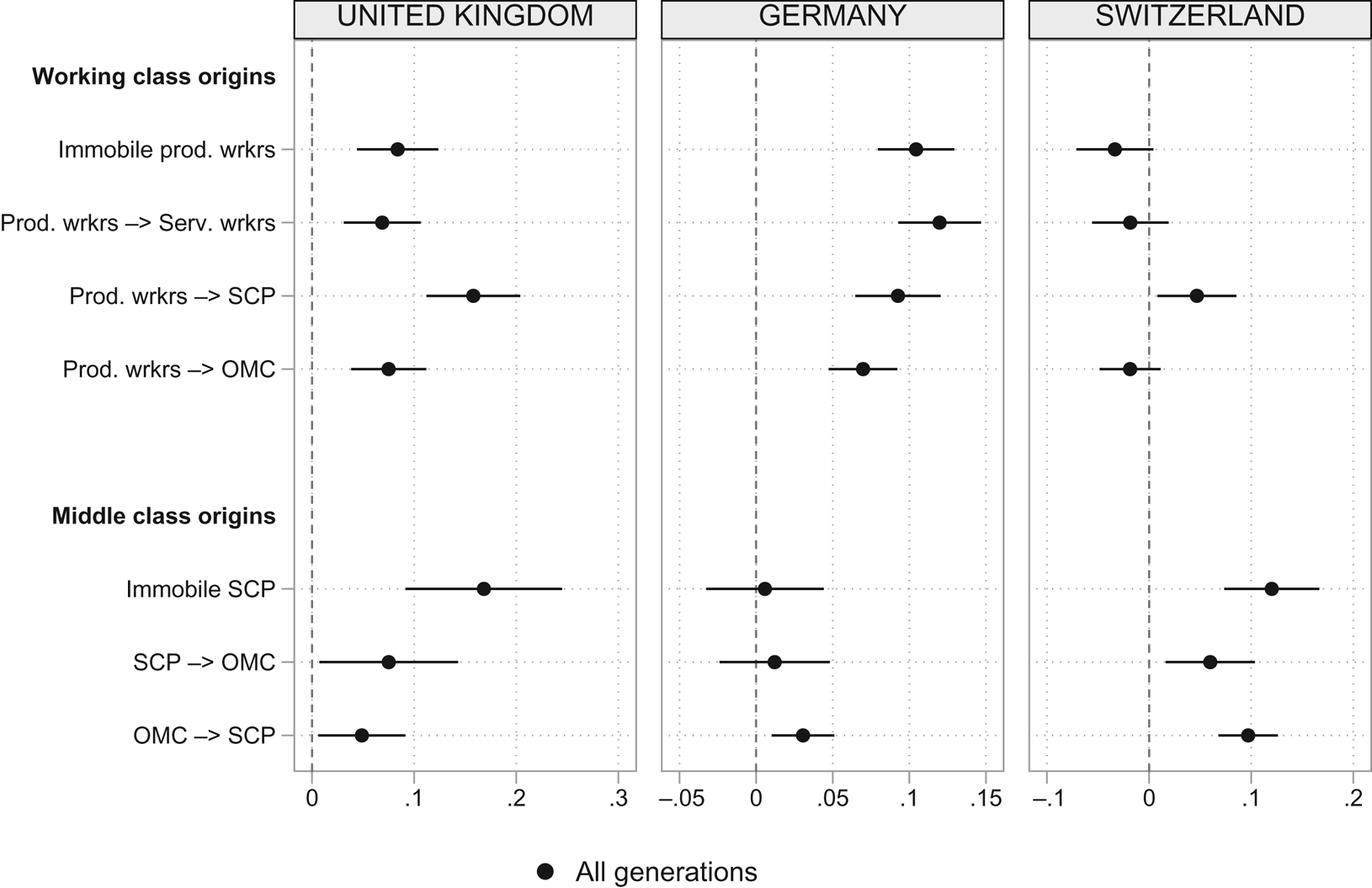

The previous analyses indicate that class of origin and destination are both related to differences in party support. Production working-class origins are more strongly related to left-wing support, whereas SCPs are more strongly aligned with the Left by respondents' class. Hence, the specific intergenerational transition between production working-class origins and an SCP destination should be particularly conducive to left-wing support. As many professionals have working-class origins, this is a frequent transition (see Tables 1–3). Figure 3 presents average marginal effects of left-wing support by different transitions of particular interest, in comparison with the immobile OMC.

Fig. 3. Impact of intergenerational class transitions on left-wing party support.

Note: Average marginal effects (with 95 per cent confidence intervals) on probability to support a left-wing party, relative to the reference category of the old middle class. Estimations based on random effect regression models in Table S3 in the Online Supplementary Material. Controls: full-/part-time work, civil status, gender and age (Germany = East/West Germany in 1989). Data are from BHPS/UKHLS 2008–19 (N = 6,301), G-SOEP 2008–18 (N = 13,167) and SHP 2008–19 (N = 6,157).

Table 3. Germany: parental class location by respondents’ class location, column percentages

Note: N = 16,658. Cells indicate for each class of destination (columns) the percentage of respondents with the respective parental class location (rows). Shaded cells indicate social immobility; off-diagonal cells indicate social mobility.

SCP = socio-cultural professionals. OMC = old middle class.

Source: Authors' calculation using G-SOEP 2008–18 data.

Table 4. Switzerland: parental class location by respondents’ class location, column percentages

Note: N = 6,503. Cells indicate for each class of destination (columns) the percentage of respondents with the respective parental class location (rows). Shaded cells indicate social immobility; off-diagonal cells indicate social mobility.

SCP = socio-cultural professionals. OMC = old middle class.

Source: Authors' calculation using SHP 2008–19 data.

We expect that intergenerational mobility between social classes that constitute left-wing constituencies is associated with particularly high levels of left-wing party support (H2a). In realigned party systems, this means that SCPs with production worker origins should be particularly likely to support left-wing parties. This is, indeed, what we observe in the UK and in Switzerland. In comparison to others with working-class origins, SCPs with those roots are even more likely to support the Left. This is an important finding because most accounts of intergenerational mobility propose that moving between classes leads to more moderate (that is, ‘less extreme’) political preferences. This, however, assumes that classes of origin and destination are equally aligned with parties. In a context of realignment, however, this is not a given, as social mobility does not necessarily entail moving between classes with different political allegiances. Similarly anchored in this process of realignment is the result that immobile production workers are not particularly aligned with the Left. In fact, they display similar preferences as those who move upward into the OMC. This, again, is explained by the lower alignment between workers and the Left in more recent periods.

The transitions from middle-class origins, at the bottom of Figure 3, are the ones that are likely to become more common given the upgrading of the occupational structure. Here, immobile SCPs are most likely to vote for the Left in the UK and Switzerland. In the UK, this is to a similar extent as SCPs with production working-class origins, while in Switzerland, immobile SCPs display the highest levels of left-wing support. In contrast to our initial expectation, Germany appears a less realigned case than the UK. In Germany, left-wing support is equally high among immobile production workers, SCPs with working-class origins and others with the same background; also, intergenerationally immobile SCPs are not more likely than the immobile OMC to support the Left. This is explained by SCPs’ stronger alignment with the Greens (see Figure S4 in the Online Supplementary Material).

To test H2b, Figure 4 addresses how left-wing support by different transitions of intergenerational class (im)mobility vary across generations socialized during different stages of realignment. These results must be interpreted with a certain caution since disaggregating transitions by generation reduces the number of observations available for some of these groups, particularly for millennials (as demonstrated by the larger confidence intervals). Moreover, we do not present transitions out of the SCP class for baby boomers since this is an infrequent class of origin in that generation.

Fig. 4. Impact of intergenerational class transitions on left-wing party support by generation.

Note: Average marginal effects (with 95 per cent confidence intervals) on probability to support a left-wing party, relative to the reference category of the immobile old middle class. Estimations based on random effect regression models in Table S4 in the Online Supplementary Material. Controls: full-/part-time work, civil status, gender and age (Germany = East/West Germany in 1989). Data are from BHPS/UKHLS 2008–19 (N = 5,967), G-SOEP 2008–18 (N = 12,957) and SHP 2008–19 (N = 5,952).

These analyses show the clearest generational variation in line with different stages of realignment for Germany. In Switzerland and the UK, some of the generational patterns are also in line with our expectations. More importantly, none of the patterns are in direct contradiction with our expectations, especially considering the relatively high demands on the data. In Germany and the UK, we find a clear pattern of generational dealignment among immobile production workers. In the youngest generation, their left-wing support is not different from that of the immobile OMC, while this is the case among baby boomers. In fact, whereas among UK baby boomers, all production working-class origins predict higher probabilities of supporting the Left (with differences around and over 0.10, as compared to immobile OMC), among Gen X and millennials, this left-wing alignment is only manifest for those who moved into the SCP. In Germany, we do not observe this ‘realignment’ of SCPs with working-class origins (which is consistent with the analyses in the Online Supplementary Material indicating that this class has realigned with the Greens). In Switzerland, the advanced stage of realignment is evident in the low left-wing support among production working-class origins already among baby boomers. In fact, mobility into the SCP class is related to higher left-wing alignment (compared to the immobile OMC) in that generation as well.

Focusing on transitions from middle-class origins, which are becoming more frequent in younger generations, immobile SCPs are more likely to vote for the Left in the UK and Switzerland. However, there are no generational differences in the former, whereas in the latter, millennials demonstrate a significantly larger probability for left-wing support than Gen X (a difference over 0.10). While we would expect the transition out of the SCP into the OMC to be increasingly associated with left-wing support among younger generations, we observe this only in the UK. We thus do not observe a strong lasting impact of SCP socialization for most younger generations of respondents who move to a different (middle-class) location, as differences between these generations are minor in Germany and Switzerland. Finally, only Switzerland displays a left-wing effect of mobility into the SCP class (in comparison to the immobile OMC). This effect is similar across all three generations, indicating again the advanced realigned context in Switzerland.

Conclusion

In this article, we combine insights from studies on post-industrial occupational transformation and political realignment with political socialization to propose that parental class of origin matters for political preferences and continues to exert an influence later in people's lives, even after they move to a different class location. Moreover, qualifying existing research on the impact of class of origin, we argue that this socialization environment needs to be understood in view of the party–class alignments prevalent during the respective period. In a context of changing party allegiances – like current trends in post-industrial realignment – it is necessary to overcome a static understanding of the impact of class of origin. This finding is consistent with a growing body of literature emphasizing the importance of the political context in the articulation of class voting (Ares Reference Ares2022; Evans and Tilley Reference Evans2017).

One of the consistent findings across our analyses is the enduring impact of parental class of origin on left-wing party preferences. This implies that legacies of past industrial alignments still ground political conflict today and that exclusively considering respondents' own class location while ignoring class of origin leads to an overestimation of the level of post-industrial electoral realignment. Production working-class origins are frequent in the three countries studied, among middle-class respondents too, and these origins are consistently related to higher support for the Left in the strictly post-industrial period under consideration. Hence, part of the left-wing turn of the middle class can be accounted for by their family origins in the working class. By neglecting the relevance of early political socialization in the class of origin, accounts of post-industrial politics may be overestimating the pace at which social transformations alter current politics. We show that even in post-industrial economies, we find a legacy of earlier patterns of conflict persisting through the socialization of younger generations. With occupational upgrading, increasingly fewer middle-class individuals have working-class backgrounds, which could imply lower levels of left-wing support in the future. However, assessing future legacies requires considering not only the relative numerical relevance of different origins, but also their (shifting) class–party alignments.

This article has documented that the legacy associated with different classes of origin depends on the configuration of class–party alignments. Post-industrial transformations and their accompanying political realignment have meant not only that the production working class is declining in size, but also that its legacy has become increasingly less favourable to left-wing parties. At the same time, we find new signs of post-industrial legacies being built, particularly among the offspring of SCPs, though they are not (yet) equally strong as those from the industrial working class.

As post-industrial realignment unfolds, industrial legacies are weakened. In fact, in an early-realigned case like Switzerland, a left-wing legacy is related to SCP rather than working-class origins, already among older generations. The comparisons by country and generation indicate that at later stages of realignment, as production workers dealign from the Left and SCP support for this bloc increases, the left-wing legacy arising from socialization in a working class is diluted and SCPs increasingly constitute a new left-wing legacy. This latter phenomenon is apparent in the results from the UK and Switzerland, while in Germany, the SCPs’ legacy is mainly in favour of the Greens. This indicates that the left-wing attachment promoted by SCP parents might benefit other New Left parties.

Analysing specific class transitions allowed us to pay closer attention to the impact of intergenerational social mobility in a context of realignment. Indeed, in the UK and Switzerland, left-wing support is particularly high among individuals who have moved between the ‘old’ and ‘new’ core left-wing electorates: SCPs with working-class origins. This indicates not only that part of the left-wing alignment of these professionals is grounded on their working-class roots, but also that it is particularly high due to the current left-wing attachment in the destination class. The process of realignment is also manifest in the comparatively lower support for the Left among intergenerationally immobile production workers in the UK and Switzerland. This finding leads us to qualify one common expectation in previous analyses of intergenerational mobility: that mobility ‘moderates’ preferences. Moving between two classes is likely to have such a ‘moderating’ effect when these classes differ in their partisan leaning, and these allegiances do not change over time. However, when class–party alignments are shifting, even social immobility can entail such a ‘moderation’ of preferences if the specific class in question is realigning. Future studies of intergenerational social mobility should therefore incorporate a more dynamic understanding of class–party alignments and consider that patterns of social mobility do not necessarily map onto ‘political mobility’ – that is, individuals might move intergenerationally between classes but could stay ‘politically immobile’ within core electorates of the same party.

Our results also provide some insights about prospective trends in left-wing support. While the working class is becoming less relevant as a milieu of left-wing socialization in younger generations and in realigned party systems, SCPs seem to generate a new left-wing legacy. However, there is some uncertainty concerning its strength and pervasiveness. First, the offspring of SCPs might opt for other left-wing alternatives, as shown by the German case. Secondly, the disaggregation by transition and generation shows some patterns of weaker intergenerational legacies in the UK and Switzerland. For instance, OMC citizens with SCP roots are less prone to support left-wing parties than are immobile SCPs, and in the youngest generation in Switzerland, their party support does not differ from the immobile OMC. This could indicate that the newer left-wing legacy of post-industrial classes is not equally lasting after individuals move to a different class location. Class identity and the intergenerational transmission thereof were likely more important in industrial societies, together with the class-based appeal of traditional left-wing parties, leading to a stronger legacy of socialization in class of origin compared to newer left-wing constituencies. The relevance of class of origin among newer, post-industrial, class constituencies could strengthen as realignment consolidates but may operate through different mechanisms than under the industrial logic. Additional research is needed to better understand the (lack of) development of left-wing legacies among classes of younger and future generations of voters.

Supplementary Material

Online appendices are available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123422000230

Data Availability Statement

Analysis replication files for this article can be found at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/XKSUPV. This study has been realized using data collected by the BHPS, the SOEP and the SHP. The data are available for the academic community through a user agreement. The BHPS is published by the Institute for Social and Economic Research (ISER), University of Essex. The SOEP is published by the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW), Berlin. The SHP is based at the Swiss Centre of Expertise in the Social Sciences (FORS), and the project is financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Alexandra Cirone, Silja Häusermann, Thomas Kurer, Guillem Vidal and the editor and three anonymous reviewers of the British Journal of Political Science for their helpful comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this article, as well as participants at the 2020 conference of the Swiss Political Science Association and the 2019 conference of the European Political Science Association.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to the article and are listed in alphabetical order.

Financial Support

None.

Competing Interests

None.