Introduction

The aspects of the music teaching profession that attract potential practitioners may exert an influence on their future practice and reveal insights into their teaching identities. Furthermore, bringing these conceptions to the forefront may reveal valuable information for university teachers involved in teacher education and for shaping the contents of teacher education programmes. For investigating this topic, I propose the following research question, utilizing the students enrolled in the music teacher education programme at the University of Karlstad in Sweden as the case under scrutiny: What do pre-service undergraduate music teachers see as motivational or attractive regarding their future profession?

This study is part of an ongoing research project examining the attitudes and motivations within music education contexts (Project Musihabitus). The data in this research constitute thus a subset of a larger data collection process that will be reported in different forthcoming articles. Each of these research reports employs different theoretical frameworks to address its unique research questions.

Framework

Studies regarding pre-service teachers’ beliefs and the motives driving their career choices constitute a relevant body of work to frame this research. Prior to exploring these studies, I first establish a framework to conceptualise motivation in the context of the present study.

Motivation

Motivation refers to a theoretical concept for clarifying behaviour (Guay et al., Reference GUAY2010). However, there is a lack of consensus regarding its scope (Kleinginna & Kleinginna, Reference KLEINGINNA and KLEINGINNA1981). I conceptualise motivation in this study as the ‘processes that energize, direct, and sustain behaviour’ (Santrock, Reference SANTROCK2017, 438). Advancing from this conceptual assumption, ‘motives’ or ‘motivations’ may thus be defined as the ‘reason[s] offered as an explanation for or cause of an individual’s behaviour’ (VandenBos, Reference VANDENBOS2007, 281). Likewise, extrinsic motivation is based on the consequences of the act (of teaching music), while intrinsic motivation is independent of these consequences, stemming from the ‘pure’ act of teaching instead (Ryan & Deci, Reference RYAN and DECI2000).

Paralleling the lack of consensus in defining ‘motivation’, a plethora of theories coexists to explain its underlying mechanisms (for a thorough description, see Wentzel & Wigfield, Reference WENTZEL and WIGFIELD2009). As noted by Urdan and Turner (Reference URDAN, TURNER, Elliot and Dweck2005), the multiplicity and contradictions among these theories stem from their deductive origins, that is, imposing ‘an idea’ to ‘reality’. Therefore, these authors encourage researchers to pursue studies inductively on motivation, that is, departing from the praxis; which is, indeed, the methodological basis for the present research.

Motives driving career choices

There is a clear imbalance in the scholarship on the motivation driving career choices for teachers between the number of studies on music teachers compared with those on teachers in general. Regarding the latter, Cornali (Reference CORNALI2019) proposed the following overarching categorisation of the motives present in the research literature to date:

-

(1) Altruistic motives: the privilege of educating new generations, fostering positive values, the transmission of culture, etc.

-

(2) Intrinsic reasons: the teaching activity itself, nurturing a personal ability as a teacher, etc.

-

(3) Extrinsic or material reasons: fixed and long holidays, better working conditions, job security, etc.

The majority of these studies tend to find evidence that respondents prioritise altruistic or intrinsic reasons (e.g., Bruinsma & Jansen, Reference BRUINSMA and JANSEN2010; Fielstra, Reference FIELSTRA1955; Hellsten & Prytula, Reference HELLSTEN and PRYTULA2011; Stiegelbauer, Reference STIEGELBAUER1992).

Within the specific literature regarding pre-service music teachers, no study to our knowledge has fully dedicated itself to addressing the topic of pre-service teachers’ motivations regarding the attractiveness of their profession. Hence, even after nearly 20 years since this observation was made (Madsen & Kelly, Reference MADSEN and KELLY2002), the dearth of studies examining these motivations persists.

Relevant studies in this area have mainly focused on North American students as their unique participants, are mainly quantitative and often aligned with the expectancy-value motivation model (Bergee et al., Reference BERGEE2001; Hamilton, Reference HAMILTON2016; Parkes & Daniel, Reference PARKES and DANIEL2013). Among those departing from this perspective, Parkes and Daniel (Reference PARKES and DANIEL2013) found that higher expectancy beliefs were the main predictor for choosing to teach music, whereas higher intrinsic interest and attainment values drove the decision to be performers.

In addition to the aforementioned quantitative studies, Bergee et al. (Reference BERGEE2001), despite not being bound to a particular motivational theory, ranked several reasons to become a music teacher according to their participants’ responses to a multiple-choice questionnaire, as follows: ‘love of music’ (59%), ‘felt called to teach’ (18%), ‘desire to work with people’ (5%), ‘other’ (5%), ‘desire to conduct/perform/attain visibility’ (3%) and ‘teachers’ benefits’ (1%). In a similar manner, Hamilton (Reference HAMILTON2016) identified the following reasons to become music teachers: ‘Being impacted by their passion for music that they wished to share with others’ (86%), ‘to be a role model’ (82%), ‘Music education is right for me’ (e.g., referring to self-identity; 72%) and ‘Music performance being uncertain’ (e.g., referring to job stability; 68%).

From a different research perspective, a number of studies that have adopted a qualitative approach (Bergee et al., Reference BERGEE2001; Gillespie & Hamann, Reference GILLESPIE and HAMANN1999; Jones & Parkes, Reference JONES and PARKES2010) may also be related to the present study. Among these, Jones and Parkes (Reference JONES and PARKES2010), utilising a grounded theory-based analysis, identified 13 categories (analogous to motives), which they grouped into 4 themes: ‘enjoyment’ (of music, teaching and being with children), ‘ability’ (in teaching or performing a musical instrument), ‘usefulness’ (of the career) and ‘identity’ (being a role model). Similarly grounded in a qualitative standpoint, Gillespie and Hamann (Reference GILLESPIE and HAMANN1999) found the following main reasons guiding career choices among pre-service string teachers: ‘Liking teaching as a rewarding work’ was ranked first, ‘Enjoyment and love of music’, ‘Desire to enrich and share the joy of music with others’ and ‘Love of children’.

Pre-service teachers’ beliefs on the profession

Among the significant contributions found in this body of work, regarding teachers of other subjects, the beliefs on the working conditions and social status of the teaching profession are identified as relevant influences to career choices (Eren & Çetin, Reference EREN and ÇETIN2019; Eren & Tezel, Reference EREN and TEZEL2010; Tarman, Reference TARMAN2012; Yüce et al., Reference YÜCE, ŞAHIN, KOÇER and KANA2013). Regarding the specific beliefs of pre-service music teachers, identities (understood as beliefs on the self) are related to this population’s career choice and career retention (Ballantyne et al., Reference BALLANTYNE, KERCHNER and ARÓSTEGUI2012). These identities are mainly (but not exclusively) associated with an alternation of the roles of educator/teacher and musician (Conway et al., Reference CONWAY, EROS, PELLEGRINO and WEST2010; Hargreaves & Marshall, Reference HARGREAVES and MARSHALL2003; Hargreaves et al., Reference HARGREAVES, PURVES, WELCH and MARSHALL2007).

In regard to non-identity beliefs, Kos (Reference KOS2018) identified three overarching themes, which may also be considered reasons to choose the profession: ‘A desire to share and develop passion’, ‘Expressing, feeling, and emotional growth’ and ‘Providing opportunities for all students’. Complementary to these beliefs, Legette and McCord (Reference LEGETTE and MCCORD2014) found the following as most rewarding: ‘making learning fun for students, helping students to grasp new skills, observing beginning students performing their first musical composition, showcasing students, and maintaining high standards’ (Legette & McCord, Reference LEGETTE and MCCORD2014, 169).

While many of the studies above centre on the North American context, Georgii-Heming and Westvall’s (Reference GEORGII-HEMMING and WESTVALL2010) research, conducted in Sweden, may also be connected to the present study. The participants in this study particularly highlighted the importance of collaborating with school colleagues and their interests in the social values of music education; with the primary aim to ‘equip their students for musical participation on a personal and societal level, and also to provide a broad musical basis from which a professional commitment to music may grow’ (Georgii-Heming & Westvall, Reference GEORGII-HEMMING and WESTVALL2010, 364). Furthermore, Swedish pre-service music teachers are notably interested in their future professional development and display an inclinitation to enhance their future students’ motivation through extrinsic motivators (Mateos-Moreno, Reference MATEOS-MORENO2022a). In addition, the family environment is also suggested as a relevant factor influencing the choice of a music teaching career within this context (Mateos-Moreno & Hoglert, Reference MATEOS-MORENO and HOGLERT2023).

Methodology

I will begin by outlining the research design, specifically the case study approach. Thereafter, I will describe the targeted case and then present the methodology for data collection and analysis.

A case study

The research design employed in the present study is a case study (Stake, Reference STAKE1995), with the case involving pre-service music teachers enrolled at the University of Karlstad in Sweden. Case studies allow an in-depth exploration of the complexity and uniqueness of a particular topic from multiple perspectives in a real-life context (Simons, Reference SIMONS and Leavy2014). The chosen case is particularly compelling for exploring this topic due to its prestige within the Nordic countries and the substantial emphasis on teaching practices integrated into its music education program since the first year; thereby enabling students to develop particularly well-informed beliefs about the profession (Mateos-Moreno, Reference MATEOS-MORENO2022b).

Describing the case

Tertiary music education in Sweden is rooted in the conventional conservatory tradition (Brändström & Wiklund, Reference BRÄNDSTRÖM and WIKLUND1995). Before enrolling, potential students must pass an audition that tests their theoretical and practical skills in music. Teacher education in Sweden has thus been described as an ‘elite education’, as opposed to an education open to all (Sjögren, Reference SJÖGREN, Sjögren and Ramberg2005). However, this situation has since changed, in line with a process of democratisation and globalisation (Georgii-Heming & Westvall, Reference GEORGII-HEMMING and WESTVALL2010). Nowadays, ethnic, social, and knowledge diversity is prevalent among Swedish students at the tertiary level (Beach, Reference BEACH2019).

The Ingesund School of Music (Musikhögskolan Ingesund, MHI) is one of the facilities at the University of Karlstad in Sweden, a small town in the Swedish countryside. This college is one of eight that offers the music teacher degree in Sweden. MHI dedicates itself to the training of both music teachers and music performers. Its programme in music education consists of five years of training, resulting in a teacher in music degree. The education offered is broad in scope, providing students with the opportunity to specialise in primary education (i.e., from 7 to 15 years old) and upper secondary education (from 16 to 18 years old), according to the Swedish education system. Regardless of the specialisation chosen, students with this degree are also allowed to work as folk school teachers (Swedish folk schools offer specialised music education, though not attached to a degree, but as preparation for enrolling in tertiary education), or Music/Art School teachers (Musikskola/Kulturskola, which are the Swedish municipal music/art schools for children and adults). However, MHI’s strongest tradition resides in its education of high school teachers who are very skilled musicians as well. Thus, developing not only pedagogical but also musical competencies is mandatory at this institution, with a strong emphasis on fostering high-level skills in one or more instruments within any of the three different orientations offered (i.e., classical music, rhythmic/improvised music or folk music). Haglund (Reference HAGLUND2014) published the latest report on students with a degree from MHI, revealing that music education students at MHI are very satisfied with their preparation, especially regarding the connection of subjects to practice, as well as the close relations established with teachers and staff. Moreover, the last assessment by the Swedish Higher Education Authority (Lind et al., Reference LIND2019) graded the music teacher training programme at MHI with the highest qualification, highlighting how this programme connects theory and practice.

Data collection

The research instrument for obtaining data was a written interview prepared using Survey and Report software. A reduced sample (n = 3) of the targeted population piloted the interview, resulting in the rewording of some sentences. Thereafter, the same sample was surveyed again and agreed on the intelligibility of the research instrument, with no further suggestions. The questions included in the interview could thus be classified into the following blocks:

-

(1) Socio-demographic aspects: Gender and age.

-

(2) Motives: A character-unlimited field for answering the questions ‘Why do you want to become a music teacher?, What is attractive about your future profession as a music teacher?’

-

(3) Complementary questions for characterising the sample: Main instrument, aimed level/context for future work as a music teacher, the musical style of specialisation, and course year.

Given that some participants could be students of the author at the time of the study, the interview protocol highlighted that participation was fully voluntary and anonymous. The researcher sent an invitation email containing this information and a link to participate to all students (n = 98) enrolled in every year of the music education programme.

Data analysis

The methodology used was content analysis (Krippendorf, Reference KRIPPENDORFF2004). It may further be related to case-oriented quantification, as numerical descriptive data are also supplied in this study. Case-oriented quantification is a valuable addition to case studies that provide a better understanding of the case, thus facilitating the exportability and generalisability of the study results (Kuckartz, Reference KUCKARTZ and Kelle1995). Furthermore, in the case of this study, quantitative analysis enables the quantification of the collective significance of the identified motives and the inference of their rank.

The analysis process was undertaken by two researchers: the author and an experienced colleague, now retired after many years of teaching in music education at the university level. We built the codes inductively from the statements provided in the interviews using constant comparative method (Glaser & Strauss, Reference GLASER and STRAUSS1967). In doing this, we segmented the text, staying as close as possible to the data when labelling the codes, and focused on counting and ordering them, as is usual in content analysis. Following the independent coding process, the two coders discussed their findings and agreed upon a definitive code system. The data were then recodified, and Kendall’s coefficient of concordance was calculated, showing a value of W > .85 (p < .05). MaxQDA software was used in this process.

Regarding the following phase, that is, categorisation, the categories were also discussed and agreed upon with the colleague who collaborated on the previous phase, although no quantitative indicator was calculated. We distanced ourselves from the manifest content, to carry out a more interpretative process. By elaborating on the theoretical framework of this research, as well as pursuing multiple readings of the codes and their referred texts, a categorisation of the codes was achieved into different levels of hierarchies. Given the subjective nature of this process, many categorisations were thus possible. The criterion used for choosing among all of these possibilities was Occam’s razor, that is, ‘entities should not be multiplied without necessity’ (Schaffer, Reference SCHAFFER2015, 645).

Results

I will now provide descriptive data on the sample and introduce the results of my analysis. To illustrate these results, quotations will be included under the principle of ‘Authenticity’ (Lingard, Reference LINGARD2019). This approach is guided by the question: “Does the quote offer readers first-hand access to dominant patterns in the data?” (Lingard, Reference LINGARD2019, 360).

Characterising the sample

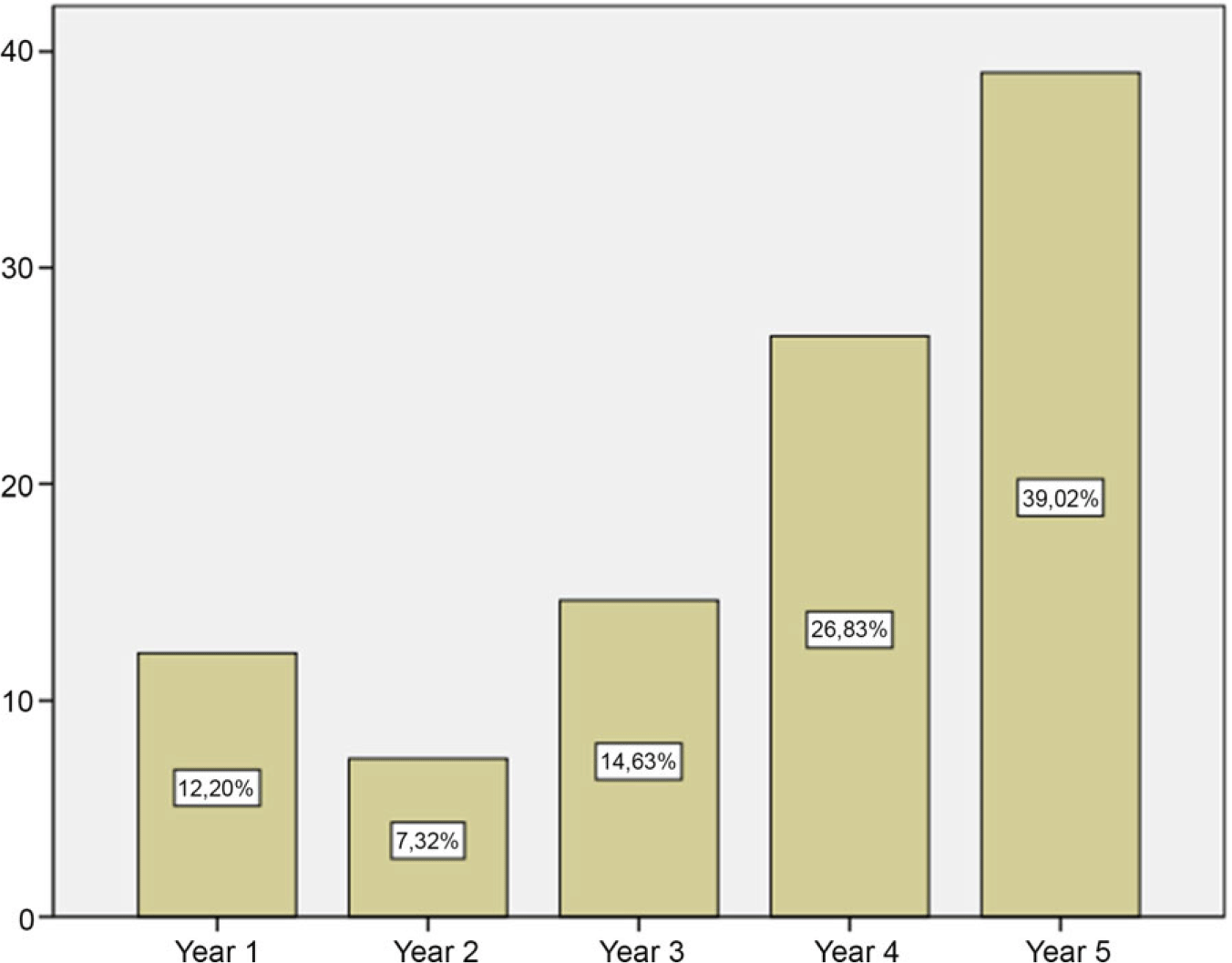

There was no missing data, as all respondents answered every question in the interview. The sample (n = 41) consisted of approximately 42% of the entire target population. Among those interviewed, the percentage distribution was approximately 60% women and 40% men. Respondents’ ages ranged from 20 to 30 years. Concerning the aimed context for future professional development, the majority of respondents (79%) saw themselves as teachers in either Music/Art Schools, Secondary/High Schools, Folk School or Primary School. The cohort of respondents included students enrolled in each of the 5 years towards the completion of the degree in music teaching at the University of Karlstad (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Percentage of respondents per year of study.

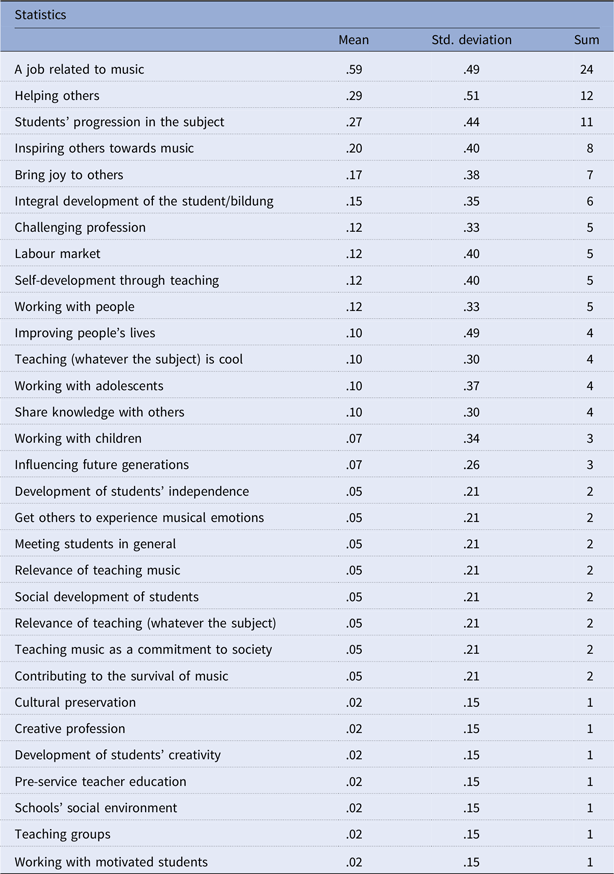

Emerging codes

Regarding the analysis process, even if saturation was found after scrutinising approximately half of the interviews, all the retrieved interviews became part of the analysis. An overall summary of the codes generated from the analyses, as well as the related descriptive statistics, is shown in Table 1. A description of the coding rationales and the hierarchical categorisation levels is given in the following sections.

Table 1. Identified codes and related descriptive statistics

Top-ranked codes

At the top of the most frequent codes, with a manifest difference from the others, lies ‘Working in something related to music’. This code was repeatedly identified (n = 24) in different ways, such as:

As a music teacher, one also gets the opportunity to continue musicking.

To be able to work with the subject that I love.

It is cool to work with music.

‘Helping others’ (n = 12) was the second most frequent code among respondents. It was typically used in emotional expressions, that is, connected to passions or emotional rewards, such as:

I am passionate about helping others

Get to feel the rewarding feeling of helping someone make progress in their music-making

The kick it gave to find the right way to help an individual

With approximately the same frequency of the previous code, the code ‘Students’ progression in the subject’ was identified (n = 11). The expressions coded were often short and contained a direct reference to the concept of progression/development, for example:

Noticing students’ development is wonderful.

To guide others […] in their progression within music.

I am motivated by […] the humility I feel for their [students’] development and future life.

Medium-ranked codes

The most frequent code at this range was ‘Inspiring others towards music’ (n = 8). In a similar way to the prior code, this was in many occasions identified within short expressions directly mentioning a word, that is, motivation/inspiration. Similarly, assertions coded within ‘Bring joy to others’ (n = 7) are typically identified by the use of single words, such as ‘joy’ and ‘happiness’, in the sense of passing on one’s passion.

In the code ‘The integral development of the student/bildung’ (n = 6), the word ‘bildung’ was chosen as a code label to mirror the Germanic concept of development of the person as a whole. This is envisaged to involve, as a consequence of music education, the development of aspects not specifically related to music, such as personality and life skills (Liedman, Reference LIEDMAN2011).

Four codes were identified with equal frequency (n = 5). Two are related to the profession: ‘Challenging profession’ and ‘Labour market’. Regarding the first, it appears the rewards of overcoming difficulties or tackling the specific complexities of the profession are attractive. The expressions representing this concept are varied. For example:

Teaching is attractive since it is a demanding job with many different challenges and opportunities.

To find what each student needs and how [it] learns best.

To overcome hindrances.

As I realise more and more how complex and exciting the profession is.

What is seen as alluring in relation to the possibilities for the future professional life (coded in ‘Labour market’, n = 5) is varied, too. This includes the ease of finding a job, the ability to change workplaces, steady income, and that there is less competition for teaching than for jobs as a musician.

‘Self-development through teaching’ is counted within this lowest part of the medium-range frequency (n = 5), too. This code attained expressions in relation to the reciprocal influence among students and their teacher, as well as their own discoveries in the subject as a consequence of teaching it. Finally, the code ‘Working with people’ (n = 5) directly alluded to the rewards of being in touch with colleagues, students, and people in general.

Low-ranked codes

Certain codes in this range may be related to other higher-ranked codes. For example, ‘Working with adolescents’ or ‘Working with children’ (low-ranked codes) is conceptually related to ‘Working with people’ (medium-ranked codes). In such cases, the difference lies in the specificity level, that is, working with people in general versus working with a specific group (children, colleagues, etc).

Isolated codes

A total of seven codes were identified as occurring in only one instance each. Several codes related to creativity belong to this lowest range, such as ‘Creative profession’ and ‘Development of students’ creativity’. Some expressions in direct reference to the students, such as ‘Working with motivated students’ and ‘Teaching groups’, were also codified in this range.

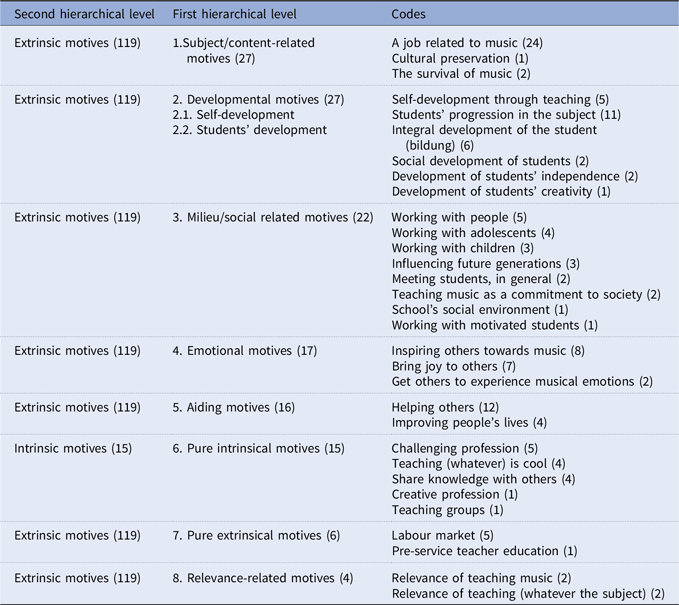

Emerging categories

Within this stage of analysis, I investigated how the codes could be grouped into categories following the methodology described in the ‘data analysis’ section. See Table 2 for a complete representation of the categories and hierarchies resulting from this stage. Towards the elaboration of the first hierarchy of categories, the codes were structured in common topics, that is, higher-order themes that encompass a number of codes. The hierarchy at the second level is rooted in the theory of motivation described in the ‘framework’ section of this study, given that a classification based on grouping the motives as belonging to intrinsic or extrinsic motivation proved to be the most parsimonious.

Table 2. Categorisation of codes

Note: The number in brackets represents the frequency of codes that were found within its corresponding category.

Discussion

According to the second hierarchical level of categories that emerged in the results of the present study, the motivation to teach music is overwhelmingly governed by extrinsic reasons among this sample of respondents. Music-related work is reported as the most attractive aspect of the profession, following the findings that emerged from the first hierarchical level. The aforementioned two results are compatible with the main conclusion of Parkes and Daniel’s (Reference PARKES and DANIEL2013) study, despite their participants were based in North America: the intrinsic interest and values of the profession are found to be mainly related to music, while the expectancy beliefs are mainly related to teaching. Moreover, approximately half of the participants in their study declared that they did not think about teaching while studying music at the tertiary level. Similarly, Ballantyne et al. (Reference BALLANTYNE, KERCHNER and ARÓSTEGUI2012) concurrently suggest that reasons apart from teaching dominate career choices in music education among students from Spain and Australia. As a result, the present study and those by Parkes and Daniel (Reference PARKES and DANIEL2013) and Ballantyne et al. (Reference BALLANTYNE, KERCHNER and ARÓSTEGUI2012) collectively evidence that the governance of extrinsic motives among the population of pre-service music teachers is not sample-dependent but, instead, commonly occurring. Likewise, the findings in my study corroborate the previous research’s claim that the ‘musician identity’ is prevalent over the ‘teacher identity’ among pre-service music teachers (Conway et al., Reference CONWAY, EROS, PELLEGRINO and WEST2010; Hargreaves & Marshall, Reference HARGREAVES and MARSHALL2003; Hargreaves et al., Reference HARGREAVES, PURVES, WELCH and MARSHALL2007). These results depict music teachers as a rare case among the population of teachers of other subjects, given that the majority of studies conclude that teachers (regardless of the subject) are more intrinsically than extrinsically motivated (e.g., Bruinsma & Jansen, Reference BRUINSMA and JANSEN2010; Fielstra, Reference FIELSTRA1955; Stiegelbauer, Reference STIEGELBAUER1992). This raises further questions, such as why this disparity occurs or what is differential about music compared with other subjects. An explanation might lay in the position that musical training, for example, learning to play a musical instrument, may begin at a very early age. Young students are usually expected to be musically motivated for reasons other than the long-term professional possibilities. This early motivation might remain through early adulthood when a career choice is traditionally made. Concurrently, labour market demands for professional musicians might be considerably lower (and thus, the required standards higher) than for those working in other professions. Thus, it might be easier for a biologist or a mathematician, for example, to work in those enterprises than for a musician to get a position in any of the few orchestras that might be found in a specific city or to perform as a solo artist.

Regarding the individual motives coded in the present study, pre-service music teachers found working in something music related to be the single most attractive motive regarding their profession. While this motive is present in the majority of the related literature on the topic (Ballantyne et al., Reference BALLANTYNE, KERCHNER and ARÓSTEGUI2012; Bergee et al., Reference BERGEE2001; Gillespie & Hamann, Reference GILLESPIE and HAMANN1999; Hamilton, Reference HAMILTON2016; Jones & Parkes, Reference JONES and PARKES2010; Kos, Reference KOS2018), it is expressed in different ways, such as the ‘love of music’ (Ballantyne et al., Reference BALLANTYNE, KERCHNER and ARÓSTEGUI2012; Bergee et al., Reference BERGEE2001), ‘passion for music’ (Hamilton, Reference HAMILTON2016; Kos, Reference KOS2018) or ‘enjoyment of music’ (Gillespie & Hamann, Reference GILLESPIE and HAMANN1999; Jones & Parkes, Reference JONES and PARKES2010). Furthermore, it is commonly top-ranked in the previous quantitative studies as either the first (Bergee et al., Reference BERGEE2001; Hamilton, Reference HAMILTON2016) or second (Gillespie & Hamann, Reference GILLESPIE and HAMANN1999; Jones & Parkes, Reference JONES and PARKES2010) most frequently cited reason guiding the career choice of music teachers.

Based on the first hierarchy of categories in the results of the present study, the relevance of subject/content-related motives seems equal to that of the motives categorised as developmental; that is, to experience development either personally or among their students. This result is unique with respect to the related literature: while the category named ‘developmental motives’ in the present study might be related to that of ‘expressing, feeling, and emotional growth’ identified by Kos (Reference KOS2018), it comprises a wider meaning in the current context, governing progress in musical skills rather than an emotional sensitivity to music. This category may further be related to participants’ sentiments in the study by Georgii-Heming and Westvall (Reference GEORGII-HEMMING and WESTVALL2010), such as providing ‘a broad musical basis from which professional commitment to music may grow’ (p. 364), as well as the teachers’ agency to foster new understandings on the subject, as expressed by the case studied by Bernard (Reference BERNARD2009). However, the meaning of this category in the present study is bound not only to the development of pre-service music-teachers’ to-be students but also to their own development as well.

The social implications of teaching music, such as meeting students and working with other people, ranked third in the present study. In relation to other studies among pre-service music teachers in the United States, this motive tends to be of a lower rank (Bergee et al., Reference BERGEE2001; Gillespie & Hamann Reference GILLESPIE and HAMANN1999) or else only important in isolated cases (Bernard, Reference BERNARD2009). However, this does not hold for studies pursued in other countries, such as Sweden (Georgii-Heming & Westvall, Reference GEORGII-HEMMING and WESTVALL2010; Mateos-Moreno, Reference MATEOS-MORENO2022a) or Ireland (Kenny, Reference KENNY2017), where the social values of music and music teaching seem to be stronger reasons for practicing the profession. Accordingly, this finding might signal sample dependence concerning this motive.

In relation to lower-ranked motives, the category labelled as ‘aiding motives’ from the first hierarchical level reached a modest fifth place among the eight categories in the present study. While this category is scarce among the previous literature regarding pre-service music teachers (e.g., Legette & McCord, Reference LEGETTE and MCCORD2014), it is quite common among those regarding teachers of other subjects (e.g., Müller et al., Reference MÜLLER, ALLIATA and BENNINGHOFF2009; Cornali, Reference CORNALI2019; Yong, Reference YONG1995). Furthermore, the category called ‘altruistic reasons’ is top-ranked among the overall career motives among non-music teachers (Fielstra, Reference FIELSTRA1955; Stiegelbauer, Reference STIEGELBAUER1992), underscoring the differential profile of music teachers compared with those in other subjects.

The perceived relevance of the teaching profession, that is, the relevance of teaching music or other subjects, was the lowest-ranked motivational aspect according to the first hierarchy identified in the present study. This result is in partial consonance with that of Jones and Parkes (Reference JONES and PARKES2010), where such a motive was also present, though not top-ranked. Conversely, this motive seems more relevant in studies of non-music teachers (Eren & Çetin, Reference EREN and ÇETIN2019; Eren & Tezel, Reference EREN and TEZEL2010; Tarman, Reference TARMAN2012; Yüce et al., Reference YÜCE, ŞAHIN, KOÇER and KANA2013). Therefore, it might be that the music teaching profession is not specifically seen by our music teachers-to-be as significantly contributing to society. Such an opinion may be a natural consequence of a society that prioritises technology over the humanities.

Conclusions and implications

Compared with their non-music counterparts, pre-service music teachers possess a particularly unique profile. The prevalence of their extrinsic motivations to teach has serious implications, as it might undermine their intrinsic motivations in the long term (Deci, Ryan, & Koestner, Reference DECI, RYAN and KOESTNER2001). For example, demotivated professionals and frequent career changes might be natural outcomes of such an extrinsic orientation. Therefore, this study provides evidence of the necessity of fostering the intrinsic motivation of pre-service music teachers.

On the other hand, the high relevance of ‘developmental motives’ to these prospective music teachers offers additional implications worth noting: if the teacher’s motivation is strongly linked to experiencing their students’ progress or development, when this progress is not apparent during the lessons (which may occasionally occur even with motivated students), the teacher’s motivation may similarly decrease significantly. This mutual reinforcement between the teacher’s and the student’s motivation mirrors that of the Pygmalion effect (Rosenthal & Jacobson, Reference ROSENTHAL and JACOBSON1992), where high expectations lead to improved performance in a certain subject. It would be desirable, instead, that a teacher’s motivation be guided by the intrinsic challenge of motivating a demotivated student in the first place.

Limitations and further research

There are two key limitations to this study: first, the sample independence of the results, and second, the loss of spontaneity in asynchronous interviews and the impossibility of repeating questions. Accordingly, further studies pursued with different participants and with different methodological standpoints may allow a better understanding of this population’s motivation and how it may be geographically or contextually dependent. Similarly, exploring whether the prevalence of motives varies with the year of study within the teacher training period or in relation to other possible variables (such as age, instrument, attitudes towards teacher training, and socio-economic or demographic aspects) would enhance the academic knowledge of its formation. Finally, exploring demotivational arguments and comparing the resulting categories with those in the present study may also provide interesting insights into the motivations towards the music teaching career, as identified by pre-service music teachers.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude for the invaluable assistance provided by Prof. Gunnar Näsman (Musikhögskolan Ingesund) throughout the course of this study.

Funding statement

The authors disclose receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Spanish Research Agency (Agencia Estatal de Investigación, MCIN/AEI /10.13039/501100011033), under grant to Project Musihabitus (ref. PID2020-118002RB-I00). The article has been published as an Open Access publication under an agreement (providing funding for open access charges) between Cambridge University Press and the University of Malaga.

Competing interests

I declare no competing interests.