Introduction

Is the teaching of composition suitable only for the student who wishes to become a composer? Or can children be encouraged to compose music as they would be taught painting and writing, for the benefit of their general education? (Ridout, Reference RIDOUT1967, p. 7)

In the mid-1960s, Ridout’s was a novel and controversial view. While composers such as Britten (Reference BRITTEN1958) and Tippett (Reference TIPPETT1958) had during the 1950s written works for performance by schoolchildren, the further step of encouraging students themselves to compose was slower to emerge. The Colston Papers Footnote 1 (Grant, Reference GRANT1963), arising from a conference held at the University of Bristol under the auspices of the Colston Research Society, published a representative selection of divergent views on what should constitute music education, largely presenting it as a recreative art. Contributing to the conference and subsequent book, Peter Maxwell Davies (Reference MAXWELL DAVIES and GRANT1963) represented the radical voice, providing an account of his work at Cirencester Grammar School where concerts featured students’ compositions (some of which feature on a recording included in the publication). Over the following decade, reports of similar practice defined a gathering momentum. Wilfrid Mellers (Reference MELLERS1964) placed student composition at the heart of the new curriculum for Music at the University of York from 1964, while composers George Self and Brian Dennis, David Bedford (Reference BEDFORD1978), and Trevor Wishart (Reference WISHART1977) made contributions to creative music education that complement the influential treatment of the topic in Paynter and Aston (Reference PAYNTER and ASTON1970). This intrinsically British achievement was investigated by R. Murray Schafer (Reference SCHAFER1963), who went on to develop a version of it in his native Canada (1975) sensitive to local cultural traditions. It represents a key contribution to the philosophy of music education internationally that has emerged over the last half-century. Laycock (Reference LAYCOCK2005) has summarised this trend as A changing role for the composer in society. This article explores the considerable and unrecognised contribution made to this trajectory by the composer and teacher Alan Ridout.

Background

This article seeks to place within the framework of the phenomenon of composition as a component of student experience in music education the unique developments that occurred at Canterbury Cathedral. Allan Wicks was appointed Organist and Choirmaster there in 1961, after appointments at York Minster and Manchester Cathedral. A superb choir trainer, and he was also one of the leading organists of his generation, with a special interest in the performance and recording of contemporary music (Moore, Reference MOORE2010). He recorded and broadcast new works frequently, including the central organ solo from Maxwell Davies’s O Magnum Mysterium and

cultivated a musical life which was ambitious and notably courageous for its day – the names of Messiaen, Ligeti, Tippett, Lennox Berkeley and Alan Ridout often nestling on the service sheet among the likes of Tallis and Gibbons. (Cullingford, Reference CULLINGFORD2010)

In a perceptive obituary for his former teacher, the organist D’Arcy Trinkwon described an aspect of Wicks’s approach that reveals a potential link with the medium of opera for choristers:

A man of letters, he passionately loved the dramatic possibilities of cathedral music in its liturgical setting and here his passion and understanding of, and for, the theatre deeply informed his sense of timing and space. (Trinkwon, Reference TRINKWON2010, p. 35)

Alan Ridout (1934–1996) had been a student at the Royal College of Music with Herbert Howells and Gordon Jacob. He went on to be one of Sir Michael Tippett’s only private students and also spent time in Holland studying microtonal music with Henk Badings (Miall, Reference MIALL1996). Aged 30 at the point that he began to work in Canterbury, he was already an established composer, published by Stainer & Bell, with two symphonies and a Concerto for Orchestra behind him as well as church anthems and secular songs (Mackie, Reference MACKIEn.d.).

Ridout first became involved with Canterbury Cathedral as a consequence of the invitation to write the children’s opera that was to be The Boy from the Catacombs. In relation to this, following a proposal of the Head Master, David Marriott, he was also engaged to teach composition to the choristers. ‘In 1964 Alan began working in Canterbury’ wrote Allan Wicks in his obituary tribute (Wicks, Reference WICKS1996), ‘and made for himself a post as composer in residence to the Cathedral and the choir school’.

A stream of compositions followed over the next decade, spanning every medium: organ pieces for Wicks, oratorio, liturgical anthems and service settings, and the first commission of the new Kent Opera. A vivid personal recollection is of Ridout’s whimsical arrangement of Preach not me your musty rules that was sung by the choristers at the ceremony on March 30th 1966 at which Princess Marina, Duchess of Kent was formally appointed as the first Chancellor of the University of Kent.

While the complete catalogue (Scott, Reference SCOTT1997) reveals an enormous quantity of orchestral and instrumental chamber music, close colleagues viewed Ridout’s heart as lying in the setting of words, and in particular in opera and music drama. His opera, based appropriately on Chaucer, The Pardoner’s Tale (1971), featured in one of the earliest seasons of the fledgling Kent Opera in a double bill with Blow’s Venus and Adonis. Both prior to and long after the works under review, opera dominated Ridout’s oeuvre, especially in the form of local educational projects. Watson (Reference WATSON1997) analysed the circumstances in which a series of pieces emerged from 1969 to 1989, many written not only for school and community groups in Kent but also for an opera, Francis, composed for Guildford Grammar School in Western Australia.

Wicks’ obituary focuses on this aspect of Ridout’s output:

[He] has an ear for English poetry. Repeatedly, he found words matched to the occasion for which he was writing; and captured the poem’s essence in beautifully crafted music. From a wide-ranging output songs, motets and anthems form the gems of his legacy. (Wicks, Reference WICKS1996)

All three of the children’s operas written for the Cathedral had their origins in poems by Damasus, Brecht and Rosetti, respectively.

Why, though, did Allan Wicks commission and direct these operas of Alan Ridout, alongside the liturgical music for which the composer remains internationally known: works such as The St Matthew Passion for the Canterbury Choral Society and The Martyrdom of Jan Palach composed for community performance in the Chapter House? There was an existing tradition in Britain of choristers performing dramatically in addition to leading the services. A photograph used to hang in the Practice Room of the Choir School of a production in Canterbury of Sydney Nicholson’s 1934 opera The Children of the Chapel, with boys in Restoration dress playing the young Purcell, Blow and their contemporaries. Wicks’ clear commitment to this form conveyed a belief that it deepened and extended the boys’ vocal experience in a manner that fed back into their performance in the choir stalls.

The choir school and creative education

A key player in the development at the Choir School both of opera and drama was the Head Master, the Rev. David Marriott, who took up his post in 1964. He subsequently moved to Wye Parish Church as Vicar in 1967, where he remained until 1994, maintaining connections with Ridout (who wrote a setting of the Communion Service for the church choir in 1970, as well as the operas Creation and The Selfish Giant) and with ex-chorister Mark Deller who presented concerts of the Stour Music Festival in the church (Burnham, Reference BURNHAM2015).

During Marriott’s short but intense Head Mastership of the Choir School, a climate of creativity prevailed which transcended the conventional performing responsibilities faced by the choristers, and which arose due to the catalyst provided by his own experience of the theatre combined with Wicks’ commitment to the avant-garde and the opportunity for boys to work with Ridout as a composer–mentor.

Ridout captured the milieu to which he contributed:

… the boys may be presented with anything from medieval music to Richard Rodney Bennett. The result is that, for example, many love the music of Messiaen, Stravinsky and Britten as well as Gibbons and Mozart – and one adores that of Boulez. (Ridout, Reference RIDOUT1967, p. 7)

As a chorister at Canterbury myself during this period, I recall a group of us huddled around my transistor radio to catch the premier broadcast on BBC Radio of Penderecki’s St Luke Passion (1966). Wicks asked us what we thought of the piece. I recall with some embarrassment referring to it as ‘sensationalist’. An older contemporary brought in a score of Stockhausen’s Gruppen, which fascinated everyone who saw it. Indeed, once ears were opened, Ridout’s own style risked being viewed as somewhat conservative. In later conversations with Ridout (personal communication 1973), as well as his written advocacy (Ridout, Reference RIDOUT1967), it became possible to place his approach in a wider context of the educational perspective on musical creativity that defined a role for composition and improvisation as central. Close parallels in the thinking of Paynter and Aston (Reference PAYNTER and ASTON1970) and Schafer (Reference SCHAFER1975) underscored the extent to which, despite opposition from those critical of this philosophy, it was beginning to assume an orthodox position (Laycock, Reference LAYCOCK2005). Indeed, one can now recognise the role that this developing trend and its underlying philosophy played in the, eventually, essential placement of composing within the original Department of Education and Science publication of the Curriculum for Music in England (1992; see also Swanwick, Reference SWANWICK1999). Composing is still integrally positioned within the statutory curricula of each of the UK’s devolved nations.

Ridout’s writing about teaching composition in Composer, from which the opening quotation is taken (Ridout, Reference RIDOUT1967), shared space with contributions by contemporaries with contrasting viewpoints. In the same issue, Morton Feldman (Reference FELDMAN1967) presented a drily sceptical account of the interpenetration of composition and theory in the American university sector. John Gardner (Reference GARDNER1967) provided the insights of another composer–educator into resources for the teaching of Fuxian contrapuntal technique. In the equivalent issue in Reference KELLER1968, Hans Keller reflected on a series of radio discussions chaired by Alexander Goehr, involving composers including Roger Smalley, Hugh Wood, Brian Ferneyhough and David Bedford, the educational implications of which he summarised in nine points. These embraced such issues as the mismatch between harmony and counterpoint exercises and the acquisition of technique relevant to the present, or the imitation of composers of the past; and one that Keller alleged was notable by its absence: the concept of sound. Such debates about the formation of composers at tertiary level echoed those about the role of music in school: Keller’s concerns are reflected in the title of Paynter and Aston’s (Reference PAYNTER and ASTON1970) book, Sound and Silence.

Ridout’s vision linked composition to the formation of the musician. He illustrated the workshop approach whereby students could compose effectively under his guidance for a specific purpose:

Fourteen boys collaborated to provide 16 items of incidental music for an internal production of OIiver Twist. (Ridout, Reference RIDOUT1967, p. 8)

In conclusion, he advocated his approach as mediating the developing relationship between the individual and their community:

I do claim, however, that for children composing music is educational in the best sense; that in writing for each other, and in playing each other’s works, it helps them to be social beings. (Ridout, Reference RIDOUT1967, p. 9)

Set within the context of the technical and aesthetic development of new music in which Ridout’s writings were published, his view of both children as creative artists and as effective performers contrasts with an alternative trend in school and youth music from the 1960s onwards: to set operas and oratorios to popular music styles with libretti derived from the Old Testament or Classical myth and the intent to amuse rather than uplift, characterised by lyrics full of puns and hyperbole devised for adult audiences, and with little or no impression that child performers can characterise or convey subtleties of emotion or psychological complexity.

School organisation and educational realities

There was another factor that played its part in the development of this initiative at Canterbury. The Choir School in which the choristers received the entirety of their education was at the time sited within the Cathedral Precincts and supplied singers able to cover the services almost throughout the year. There were over 60 boysFootnote 2 in the school, and every single one of them was there to sing. A complex structure through which boys developed in competence and fluency formed a kind of pyramid, with the 18 Singing Boys of The Sixteen at the top, responsible for most of the daily and weekend Evensongs. Tuesdays were men-only, while on Thursdays The Thirty-Six sang a trebles-only Evensong and also provided Mattins or a morning Eucharist on Saints’ Days. Four House Choirs (Byrd, Tallis, Gibbons, Weelkes) sang the late (6.30 pm) Evensong on Sunday by rotation. In order to cover the holiday periods (The Sixteen remained in residence for Christmas and Easter), a Boarder Choir and a Dayboy Choir would take responsibilities so as to permit each a modicum of holiday relief. These details are important for two reasons: the whole school was involved in the operas, partly because they were seen as an educational project in their own right, and partly as a unifying factor that gave the entire choral body a focused purpose in singing togetherFootnote 3. While, in the 1970s, the Dean and Chapter took steps to reduce the number of choristers and outsource their classroom education to St Edmund’s School, Wicks and Ridout found themselves on opposite sides of an acrimonious debate. They parted company for several years as a result, though they were later reconciled. But the numbers and depth required to continue the children’s opera tradition could no longer be sustained.

The subsequent slimming down of numbers in the Choir School occurred at Canterbury, and the effect on the vocal resources required to perform operas of this kind is worth exploring. For instance, both The Gift and The Boy From The Catacombs divide the singers into two choruses, one representing the ‘good’ characters (Peter and Martin’s friends/Christian children in the catacombs), the other the ‘bad’ (the goblins/the Roman children, the lions of the Coliseum), well-differentiated in musical representationFootnote 4. Even in the Children’s Crusade, there is a brief fight over food between different factions within the group of child survivors, for which the chorus is divided. However, in reviewing the operas as existing works, we can now separate them from the circumstances that gave rise to their composition. Granted, a choral group of some 40 or more children of different ages is required to cover their musical and dramatic dimensions. But the nature of writing would be accessible to any well-trained school or youth choirs, irrespective of gender. Indeed, research (Welch & Howard, Reference WELCH and HOWARD2002) has confirmed the acoustic and productive similarity possessed by the voices of girls and boys prior to the onset of adolescence, a position supportive of the movement to introduce girls’ choirs and mixed groupings to many cathedral and collegiate choirs in the UK.

Ridout’s Canterbury Children’s Operas

The three operas comprise The Boy from the Catacombs (Reference RIDOUT1965b), Children’s Crusade 1939 (Reference RIDOUT1968) and The Gift (Reference RIDOUT1970). Commitment to the principle of choristers gaining stage experience was also evident in a school production of Oliver Twist (Reference RIDOUT1967), for which Ridout supervised the extensive score of background music written by his chorister students. All three operas and the play were performed in the Cathedral Chapter House.

Ridout’s style in the works is chromatic, though for the most part tonally anchored in a manner that recalls the archaism of Orff, and, in the scoring for voices, percussion and piano, the Stravinsky of Les Noces. While his writing employs scalic melodic connections and triad-based harmonic underpinning, the textures are seldom free of dissonance. The means by which this tonal palette is achieved include polytonality, suggesting especially ambiguity and conflict, and octatonic harmony. Both melodically and harmonically, Ridout employs neighbour notes as colouristic devices, often linked to grace notes dislocated over an octave. Piano accompaniments make extensive and dramatic use of the entire range of the instrument.

Both vertically and horizontally, all intervals play a part, and tritones, sevenths and ninths are drawn on frequently in the portrayal of tension and its relaxation that plays such a significant part in Ridout’s dramatic and musical motivation. Indeed, intervallic colour is associated with emotional states, often through simple two-part harmony that conveys specific musical moods.

The Boy from the Catacombs (1965)

Extensive documentation of this first commission is held in the Cathedral Archives, including correspondence between Marriott and Ridout and also with the librettist selected, Frederick Wilkinson, as well as notes for programmes and for a press conference. These provide a vivid picture of how this initial project evolved, from the seed idea through to rehearsal and production. For instance, the material illustrates the need to obtain permission from the Dean and Chapter for the opera to be performed, which clearly influenced the selection of a Christian topic for this first collaboration (notably, the two later operas were not subject to the same limitation).

In a hand-written aide-memoire for a press briefing in March of that year, Ridout (Reference RIDOUT1965a) credits to the noted antiquarian Canon Derek Ingram-Hill the suggestion of the opera’s theme in response to a request from David Marriott. Indeed, it was one of three ideas proposed, and the plot that most appealed to senior choristers who discussed it with Ridout and Marriott on the occasion of a trip to sing at the St Cecilia’s service in London (Ridout, Reference RIDOUT1965a). The source was a poem by the 4th-century Pope Damasus (Reference IHM1895) about the boy saint, Tarcisius, a martyr whose death is commemorated on August 15th in the Roman martyrology (Stevens, Reference STEVENS1989). In the novel Fabiola or, the Church of the Catacombs, by the English Cardinal Nicholas Wiseman (1854), a character called Tarcisius has a minor role. A viable story and context grew from these foundations through the contribution of F. H. Wilkinson, a former head teacher with long experience of school drama, with whom Ridout had collaborated previously.

In a letter to Marriott dated 8.2.65, Wilkinson reported sending the draft libretto to Ridout for approval, adding:

It has turned itself into an exciting and a very moving story. I have intentionally kept it as a story about boys, told by boys. (Wilkinson, Reference WILKINSON1965)

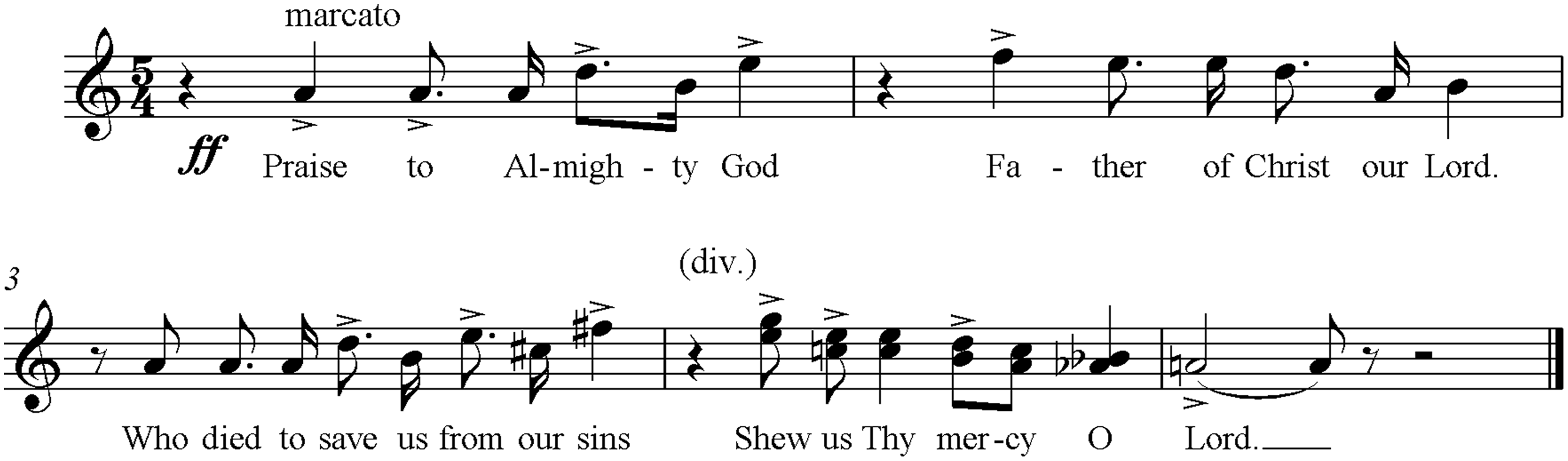

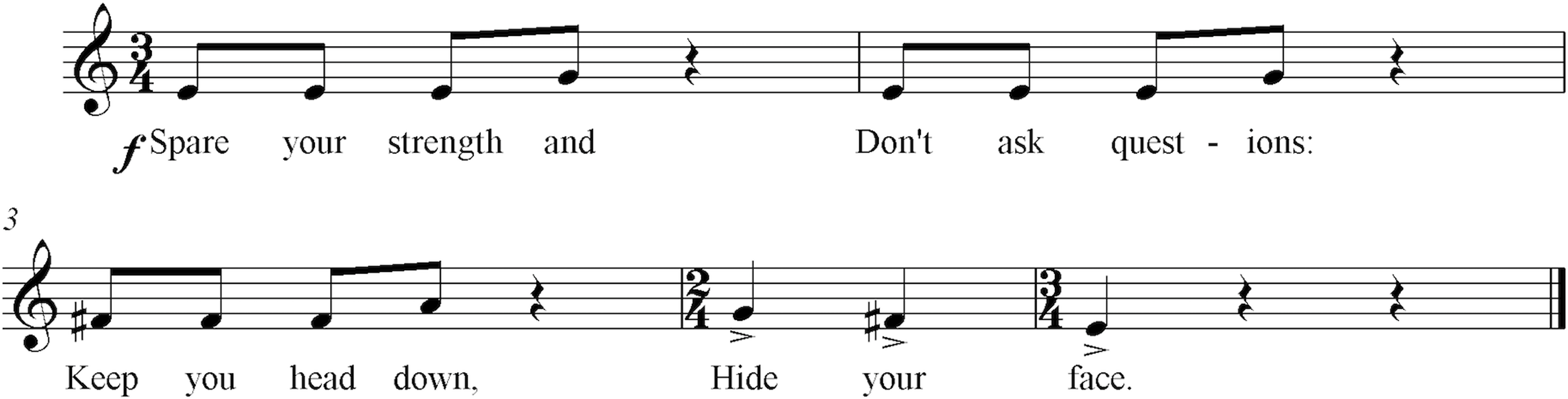

Example 1. The entrance hymn of the Christian boys, The Boy from the Catacombs.

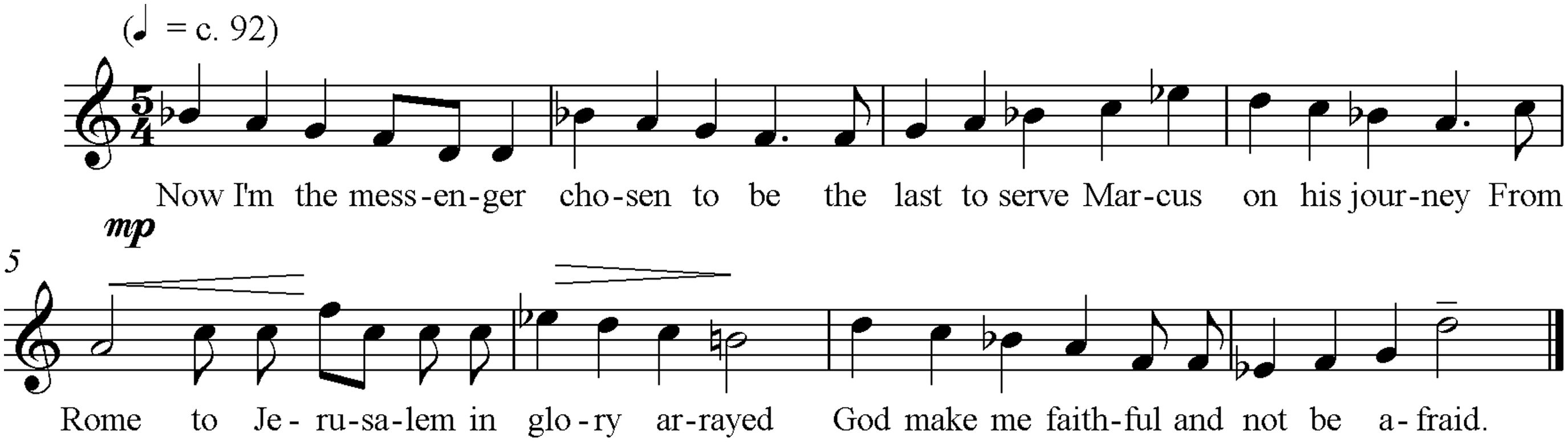

In dramatic terms, Wilkinson’s approach was to devise a structure in which the interaction of the two factions – Christian boys (Ex. 1) and Pagan Roman boys – is articulated by the playing of games that, in each case, are re-enacted as reality. At the Priest’s encouragement, the Christian boys devise a game in which pilgrims face the hazards of the trip to Jerusalem, which prefigures the mission Tarcisius is then given by the Priest: to deliver the consecrated host to the prisoner Marcus (Ex. 2). In contrast, the Roman boys dress up as the Lions vs Gladiators in a game that is reprised as the murder of Tarcisius.

Example 2. Tarcisius’s aria on acceptance of his mission.

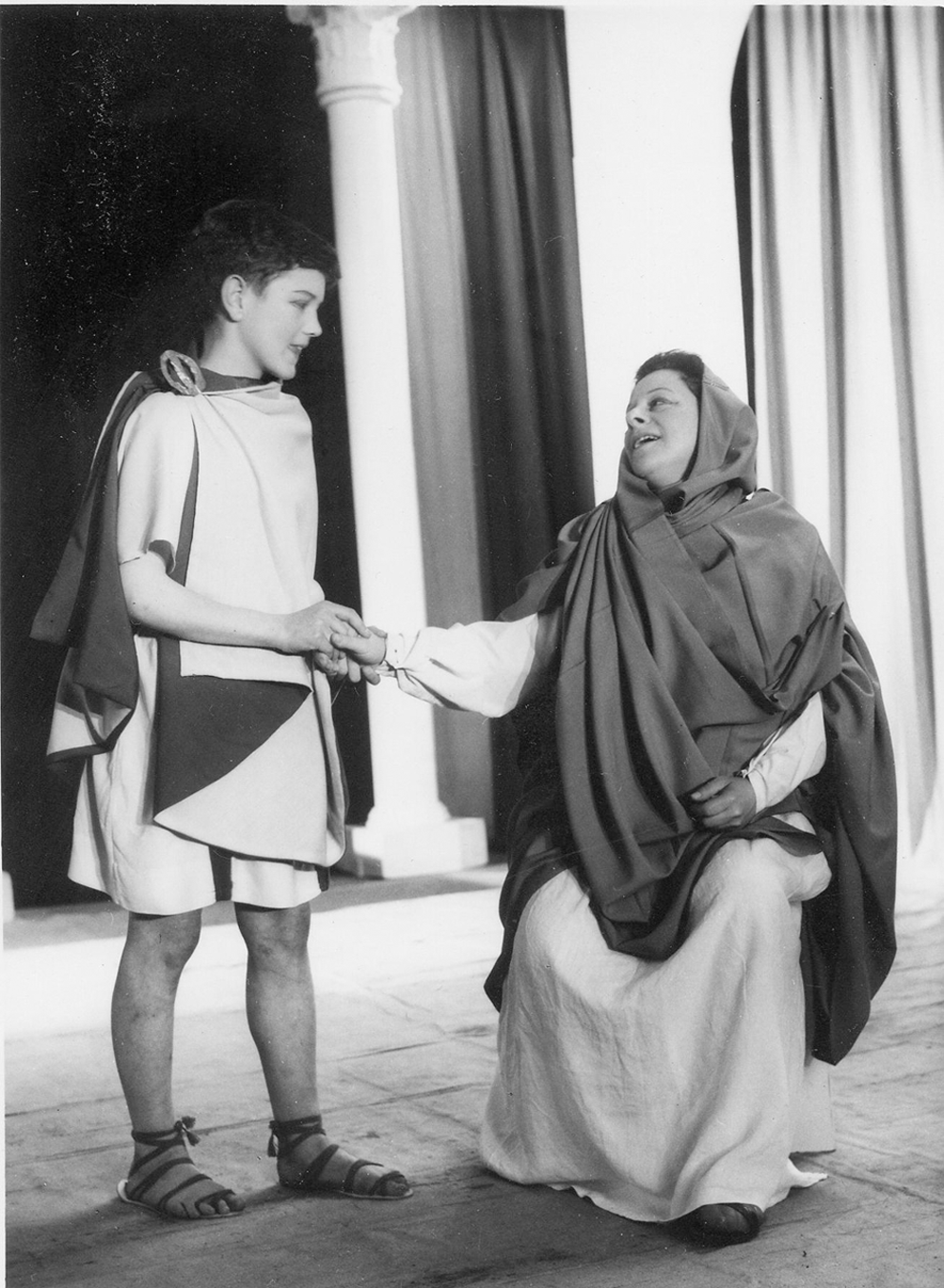

A moving perspective on the child world of the Christian and Pagan factions is provided by two adult roles: a Priest who supervises the boys and conducts the funeral of Tarcisius with which the work concludes, and the boy’s mother, who is the first to discover his murdered body.

Ingram-Hill’s inspired suggestion of this story permitted Wicks and Ridout to initiate operatic experience for the choristers through a form of paraliturgy that presents themes of faith, courage and martyrdom that parallel the content of the Cathedral services they sang daily. In the second and third operas of the trilogy, the confrontation of good and evil occurs in a more secular context.

Photograph 1. Tarcisius (Andrew Lyle) with his mother (Ilse Wolf), photograph from the personal collection of Huw Lewis, a lay clerk and teacher at the Choir School who played the Priest.

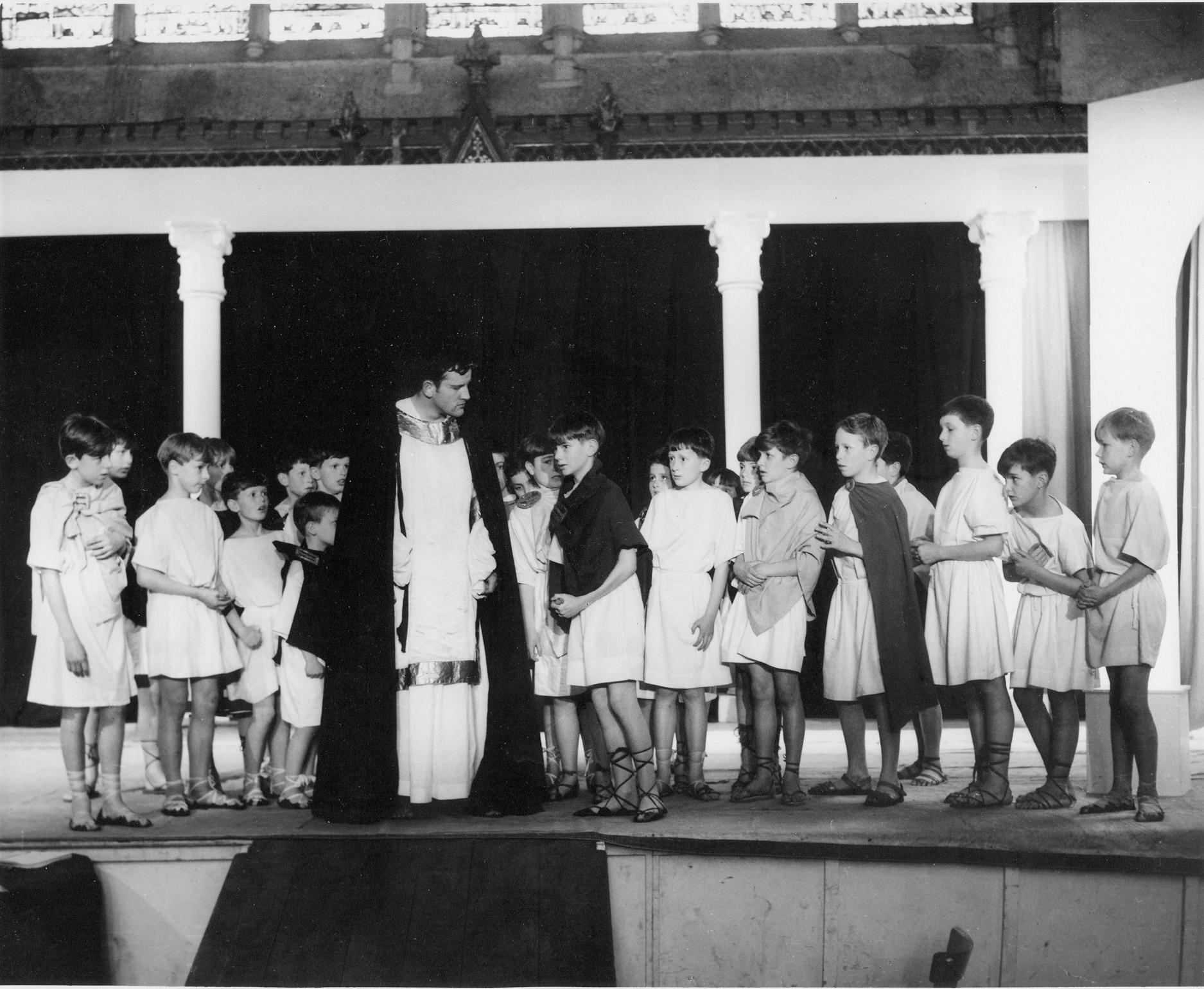

Photograph 2. The Christian boys with the Priest (Huw Lewis), photograph from the personal collection of Huw Lewis.

The Children’s Crusade 1939 (1968)

Ridout’s second opera, to a libretto adapted by David Holbrook from Bertolt Brecht’s poem Kinderkreuzzug (Reference BRECHT1949), deals with a modern recreation of the well-known Medieval narrative. After the Nazi invasion of Poland, children struggle to survive in a winter landscape in which they both reflect in their behaviour and transcend in their innocent humanity the violence wrought by adults. Two dramatic versions of Brecht’s text were licensed almost simultaneously: Ridout’s (Ridout, Reference RIDOUT1968) and Britten’s Children’s Crusade, to a translation by Hans Keller (Britten, Reference BRITTEN1969). Ridout (personal communication, Reference RIDOUT1970) admitted that he felt betrayed that the reception of his opera was eclipsed by Britten’s for St Paul’s Cathedral. He had been frustrated by William Golding’s refusal of permission for a proposed opera on Lord of the Flies, in which cathedral choristers marooned on a desert island play a significant part in the plot (personal communications with Ridout & Wicks, 1970) because Golding had apparently hated the nursery-style music that Raymond Leppard had composed for Peter Brooks’s 1963 film of the novel.

Wicks, however, found Ridout’s version compelling:

Alan gauged the boys’ ability to put themselves into a nightmarish, broken world and to sing, with heart-rending intensity, the threnody of the dispossessed; the piano and percussion accompaniment, written with skilful reticence, added to the mesmeric effect. (Wicks, Reference WICKS1996)

Example 3. Children’s Crusade 1939, main theme.

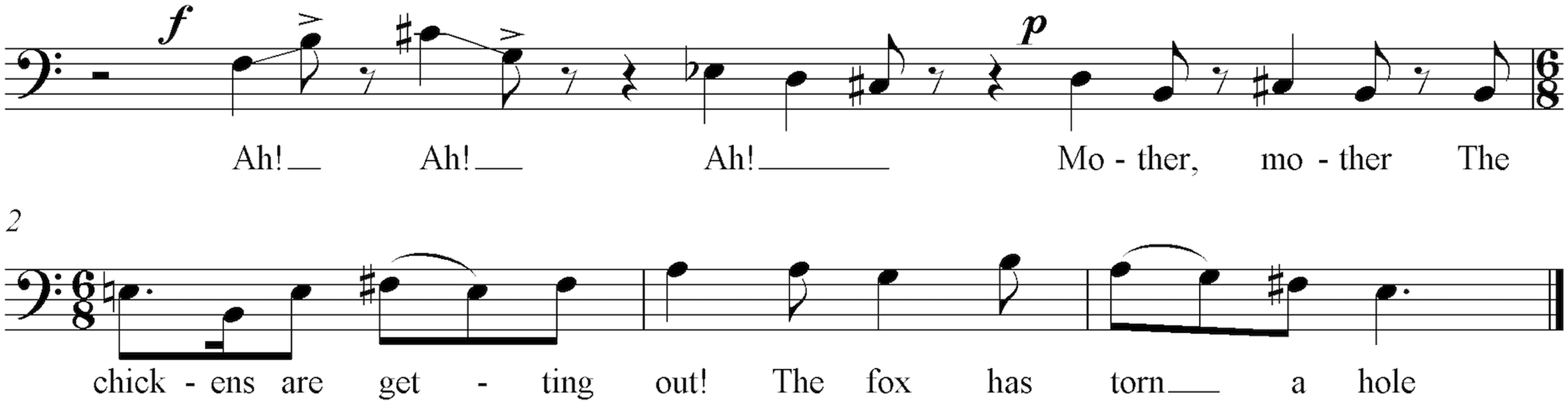

The crusade leitmotif is the stumbling chorus led by Karel that bookends the work (Ex. 3). Again, the world of children interacts with that of an adult protagonist, this time the roles reversed as it is the children who nurse a delirious wounded soldier through his final moments (Ex. 4).

Example 4. The entry of the wounded soldier.

There is no happy ending to the Brecht poem, nor to Ridout’s opera. But the piece leaves a powerful impression of how young minds cope with adversity that is bleakly uplifting.

The Gift (1970)

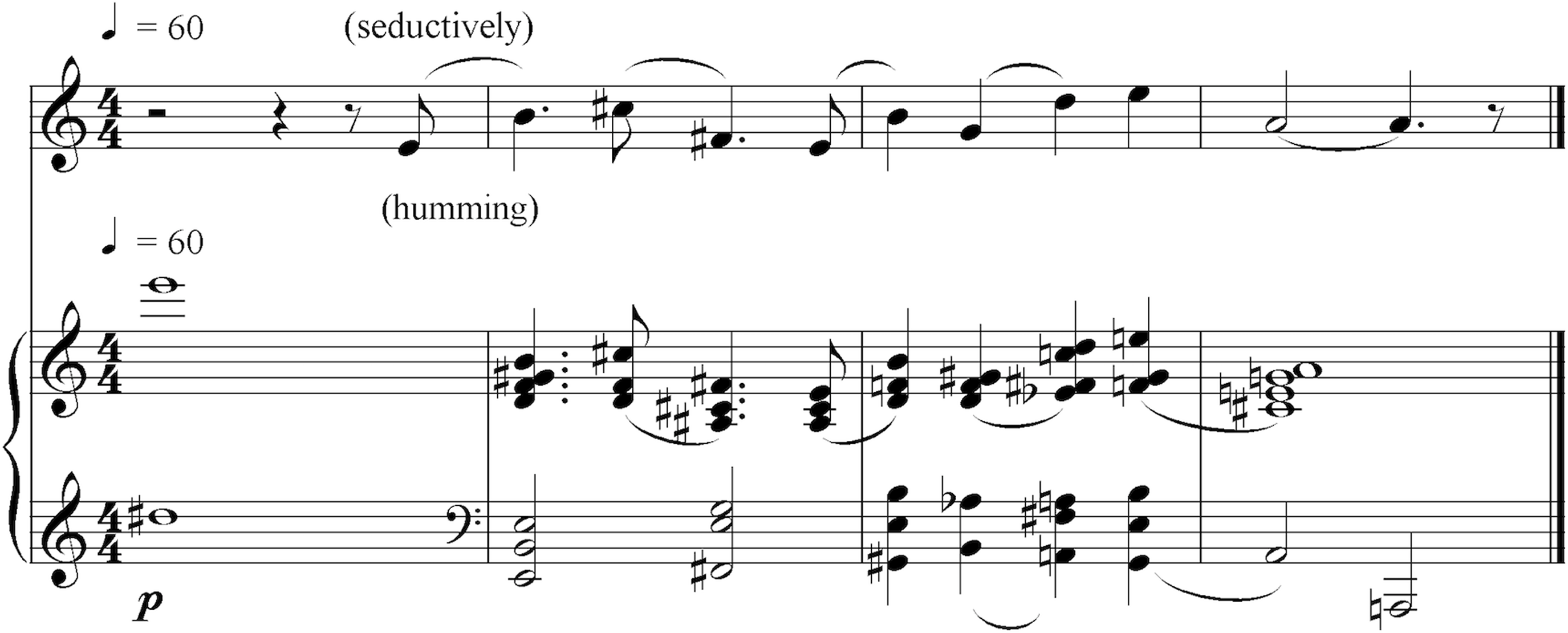

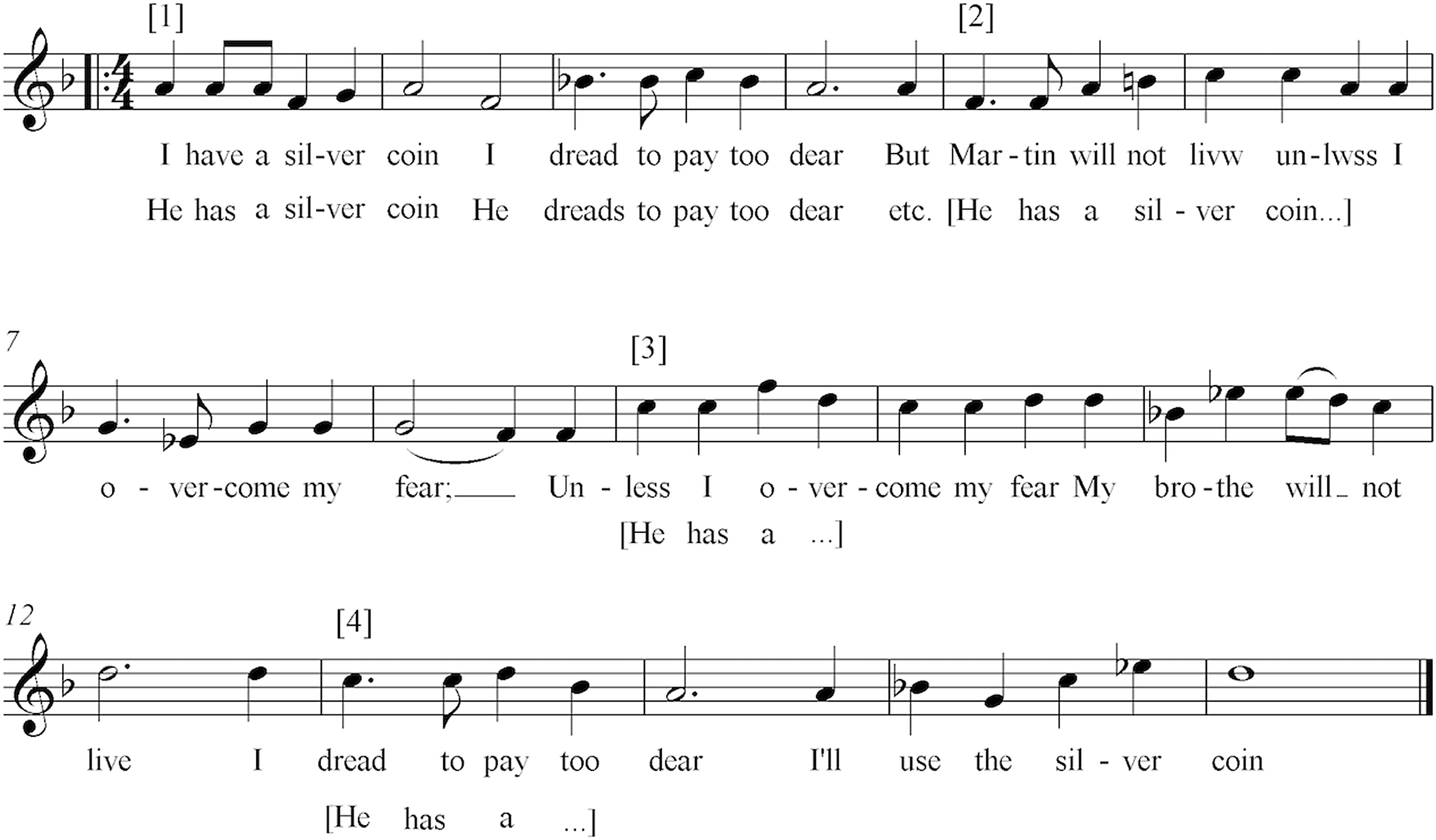

The Gift is in many ways the most home-grown of the three operas, with a libretto written by Allan Wicks himself based on the poem Goblin Market by Christina Rossetti (Reference ROSSETTI1863). The two main characters bear the names of the senior choristers who first played themFootnote 5. Sinister goblins (Ex. 5) tempt the young Martin with their forbidden fruit, and soon have him under their spell. Note the shifty, tritone-imbued harmony, which contrasts markedly with the more diatonic sound-world of the chorus of Martin’s friends and especially the closest of them, the upright Peter.

Example 5. The goblins’ wordless siren-song.

To break the spell, his friend Peter has to brave the goblins himself to supply the antidote, testing his resolve on his friends in a passage that builds a choral canon on Peter’s initial statement of the theme (Ex. 6), over which Martin’s cries of anguish emerge from the texture. The modal, imitative texture here is redolent of Cornysshe’s late-Medieval round Ah, Robin. The plot resolution unfolds with a cumulative celebration that develops from jaunty dialogue between Martin, Peter and the chorus that is followed by a second, more tonally stable canon in which the friends punch home the moral.

Example 6. The final, consolatory canon.

Conclusions

The works under review reveal themselves as intense and affecting music dramas composed by a master of the craft of writing for child performers. The example the operas laid down for the choristers’ own creative efforts bore fruit in the number of Ridout’s and Wicks’ young students who went on to compose and arrange as adults, or to perform and direct contemporary music. Where young performers are emerging today and will do so in the future capable of presenting these meaningful explorations of the human condition, boys and girls and their audiences stand to gain from the resurrection of these extraordinary creative and educational achievements.

The operatic medium is often depicted as remote from children’s experience, elitist and associated with adult voice types with which students do not identify (Bedford, Reference BEDFORD1964; Sargon, Reference SARGON1993). But scrutiny of the reception of works for young performers by Bedford, Maxwell Davies, Schafer, Ridout and their contemporaries, and recollections of their lasting effects on participants (Laycock, Reference LAYCOCK2005), illustrates that children readily accept the medium of sung drama as a means of self-expression. The intense experiences involved in conveying dramatic situations, together with exotic locations or historic contexts, play memorably on the imagination. In this respect, the Canterbury children’s operas of Alan Ridout represent a small but significant signpost from the 1960s as to the direction in which music education was subsequently to progress. Ridout, who himself loved Porgy and Bess, West Side Story and Guys and Dolls and recommended their study to his students, did not live to see the introduction into the curriculum of composition for all children that he had advocated. But his operas for child singers remain a potential inspiration to young composers and performers today.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to the following for providing materials employed in this article: Cressida Williams, Cathedral Archivist, Canterbury; Robert Scott; Huw Lewis; and the article is dedicated to the late Robert Scott (1930–2022).