1. Introduction

1.1. Context

IFRS 17 Insurance Contracts is a new accounting standard that entities are expected to apply for reporting periods beginning on or after 1 January 2023 (though earlier application is permitted). It supersedes IFRS 4 Insurance Contracts.

IFRS 17 establishes key principles that entities must apply in all aspects of the accounting of insurance contracts (e.g. recognition, measurement, presentation and disclosure). In doing so, the Standard aims to increase the usefulness, comparability, transparency and quality of insurers’ financial statements.

A fundamental concept introduced by IFRS 17 is the contractual service margin (CSM). The CSM, in most instances, represents the unearned profit that an entity expects to earn as it provides services.Footnote 1 However, as a principles-based standard, IFRS 17 results in entities having to apply significant judgement when determining the inputs, assumptions and techniques it uses to determine the CSM at each reporting period. Indeed, several aspects of the Standard have been left open for the entities to determine what approach they consider to best reflect the effect of insurance contracts on their financial position and performance. Important examples of areas where such judgement is required include the level of aggregation; the identification of contract boundaries; the determination of coverage units; the treatment of loss components (LC) and the treatment of with-profits (WP) funds. In addition to issues pertaining to judgement, there are requirements of the Standard that may create economic or accounting mismatches.

The IFRS 17 CSM Working Party was one of the three working parties established by the Life BoardFootnote 2 of the IFoA in the summer of 2018 in anticipation of the diversity of interpretation and application of the Standard. There is also a fourth working party that looks at IFRS 17 issues in the non-life space.Footnote 3 Each working party focuses on different aspects and challenges of IFRS 17 and consequently, there are few areas of overlap; our group’s objective is to analyse the technical, operational and commercial impacts of different approaches to calculating the CSM at initial recognition and subsequent measurement from a life insurance perspective.

As a standard that is still very much in its infancy, and for which wider consensus on topics is yet to be achieved, this paper aims to provide readers with a deeper understanding of the issues pertaining to the CSM and the opportunities that accompany it.

1.2. Intended Audience

The working party expects this paper to sit most comfortably in the hands (or on the screens) of readers who have prior knowledge of IFRS 17 and are broadly familiar with its various concepts and themes. However, readers with less familiarity than this need not be repelled; the paper attempts to provide sufficient exposition of the requirements (with examples where possible) to help facilitate engagement with the material presented. Experienced IFRS 17 practitioners, who already have an intimate awareness of issues, may find this paper useful to validate their own conclusions or pick up on new points of detail.

1.3. Scope

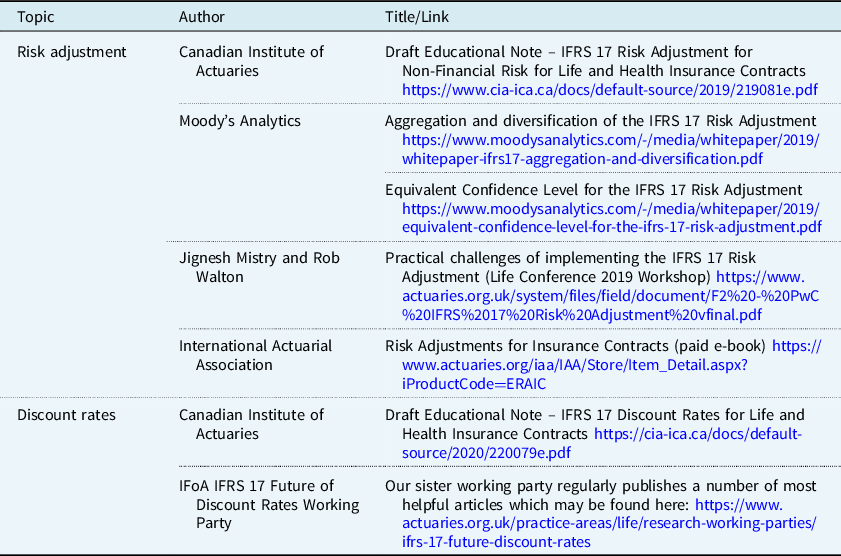

This paper aims to focus solely on issues pertaining to the CSM. As such, it is neither intended, nor should be read as, an exhaustive IFRS 17 manual. As the first truly international accounting standard for insurance contracts, IFRS 17 embeds within it an enormous amount of complexity and touches on substantial topics for which entire papers could be dedicated in their own right (e.g. discount rates or the risk adjustment (RA)). For this reason, the paper has had to be necessarily restricted to the CSM in its scope. As examples, the paper does not touch on any of the following issues in detail except to the extent that there are some points of tangential relevance to the CSM (if at all):

-

Possible approaches to determining the RA.

-

Considerations relating to the premium allocation approach (PAA).

-

Identification of non-distinct investment components (NDIC).

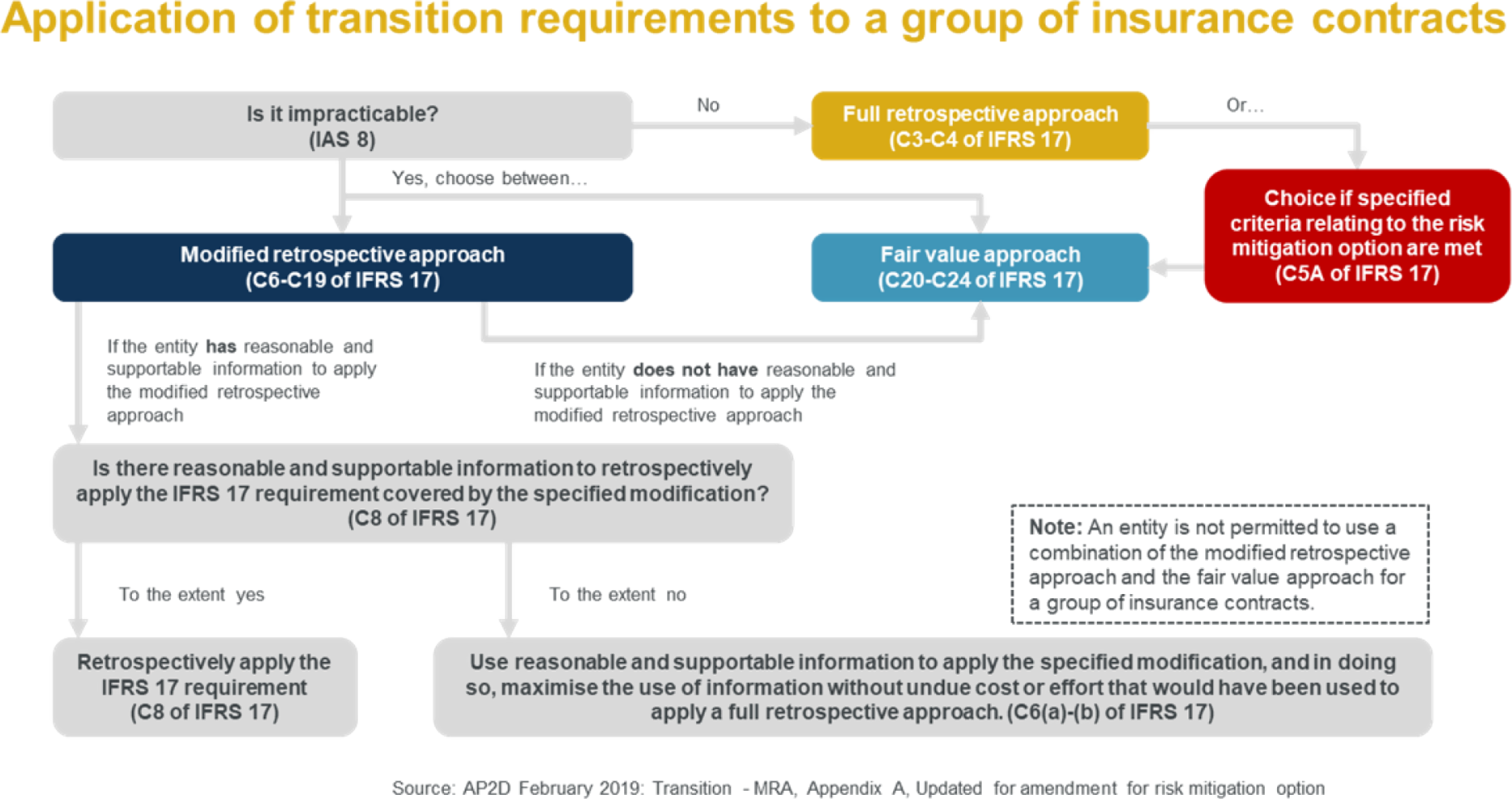

-

Treatment of acquisition costs.

-

Disclosures and presentation requirements.

-

Accounting policy choices available under IFRS 17 (e.g. OCI disaggregation; presentation of the RA in the P&L; treatment of accounting estimates made in previous reporting periods, etc.).

-

IFRS 9 requirements.

-

Designing systems and processes to comply with the Standard.

In some instances, there will be topics that our sister working parties are dedicated to examining in much more detail than considered in this paper. Here, as above, the approach taken is to only cover angles relevant to the CSM and not to cover the topic more widely. For example:

-

“How should discount rates be set based on a top-down or bottom-up approach?” is a broader question being addressed in detail by the Discount Rates working party, but “what impact does using different weighted average yield curves have on the CSM?” is a specific question that is considered in this paper

-

“What impact does IFRS 17 have on KPIs?” is a question relevant for the Transversal working party, but “what impact does the CSM have on return-on-equity?” is a specific question that is considered in this paper

1.4. Structure of the Paper

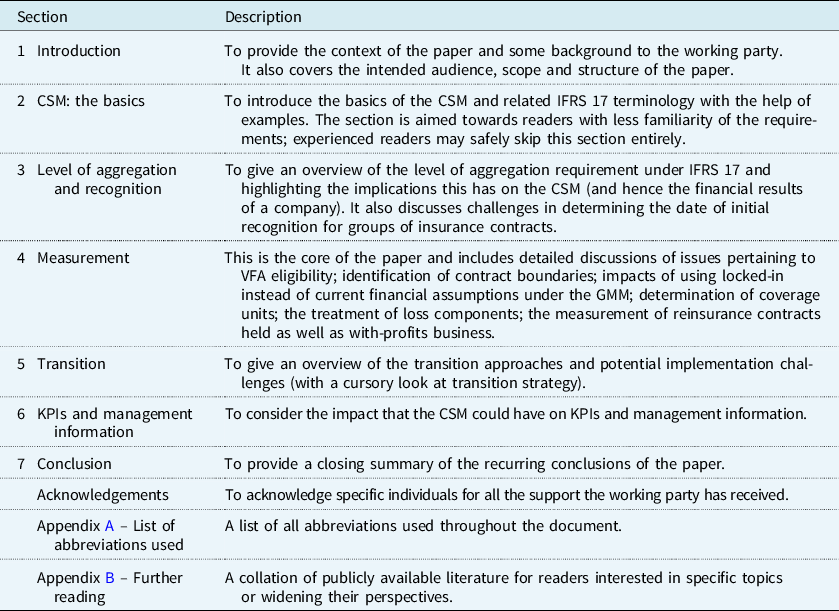

The paper consists of seven main sections followed by acknowledgements and two appendices as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Structure of the Paper

1.5. IFRS 17 References in the Paper

The paper references IFRS 17 paragraphs from the following sources:

-

“IFRS 17 Insurance Contracts” – incorporating all amendments as issued in June 2020Footnote 4 .

-

“Basis for Conclusions on IFRS 17” as issued in May 2017.

-

“Basis for Conclusions on Exposure Draft Amendments to IFRS 17” as issued in June 2019.

-

“Illustrative examples on IFRS 17” as issued in May 2017.

The paper’s approach of referring to IFRS 17 paragraphs will differ depending on the issue being covered. In many instances, it was considered sufficient to merely refer to the paragraph numbers (most of which can be found in the link in the footnote); in some instances, it was deemed more helpful to provide extracts of the paragraphs themselves; elsewhere it was judged to be appropriate to summarise the paragraphs.

2. CSM: The Basics

Section 2 covers the basics of the CSM. The section is aimed towards less familiar readers; experienced audiences may safely skip this section entirely.

2.1. Introducing the Logic of the CSMFootnote 5

The discussion starts with an introduction to the logic of the CSM. It proceeds in four parts:

-

CSM at initial recognition.

-

CSM at subsequent measurement.

-

CSM for reinsurance contracts held.

-

Recognition of the CSM in profit or loss.

By the end of section 2, less familiar readers will become acquainted with the fundamental ideas underpinning the CSM.

2.1.1. CSM at initial recognition

Consider what happens under an economic balance sheet (e.g. SII for the most part) when an insurer writes a new contract – if the contract is profitable, the insurer recognises a negative liability (effectively an asset) but if the contract is loss-making, the insurer recognises a positive liability. In either case, an economic view results in insurers capitalising, at the point of sale, the total profits or losses expected to be made under those contracts over their lifetimes.

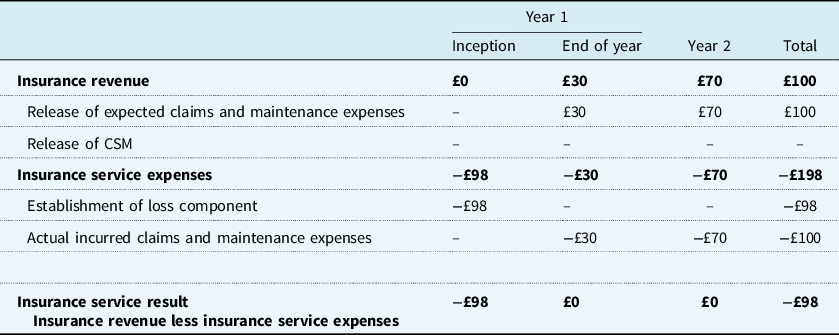

The recognition of profits or losses under IFRS 17 begins with two deliberate, asymmetric principles that are intended to depart from this economic view.

Principle 1: When an insurer writes profitable business, it must not be allowed to recognise the expected profits for that business immediately and instead must spread those profits over time (based on paragraph 38).

Principle 2: When an insurer writes loss-making business, it must not be allowed to spread the expected losses for that business over time and instead must recognise those losses immediately (based on paragraph 47).

The CSM is a fundamental concept introduced by IFRS 17 that embodies these principles at its core.

Under Principle 1, when an insurer writes profitable business, it is forced to avoid the day 1 recognition of profits through the establishment of a CSM. The CSM, in turn, can only be recognised in the profit or loss statement on a gradual and systematic basis over time, as and when insurance services are provided. At any given reporting period, the CSM consequently represents the expected amount of profits that have not yet been earned under the group of contracts in question.

Under Principle 2, when an insurer writes loss-making business, it cannot establish a “negative CSM” and defer loss recognition into the future. This is because the CSM is floored to zero in such circumstances.

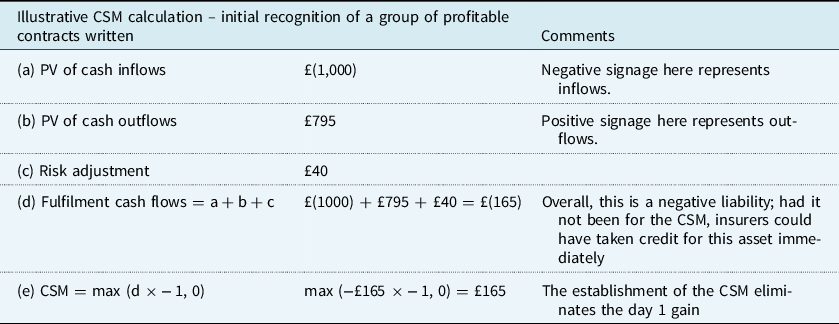

These principles can be illustrated using simplified examples as shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2. Example of CSM Calculation at Initial Recognition for Profitable Contracts

Table 3. Example of CSM Calculation at Initial Recognition for Loss-Making Contracts

At initial recognition, before any cash flows are exchanged, the two principles above would stack up as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Illustration of the contractual service margin at initial recognition.

2.1.2. CSM at subsequent measurement

Insurance business is almost invariably exposed both to the impacts of emerging experience being different to that expected and to the impacts of assumptions relating to future experience being different to that previously assumed. It stands to reason that the CSM – i.e. the balance that represents unearned profits – ought to be updated to reflect these latest facts and circumstances. IFRS 17 acknowledges both these classes of items by referring to them as “changes that relate to future service”.

Principle 3: With some exceptions (which need not be addressed in this introduction), the CSM must be adjusted for all changes that relate to future service – e.g. favourable mortality updates must increase the CSM; unfavourable lapse experience must decrease the CSM (based on paragraphs 44(c) and 45(c)).

An example is shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Example of CSM Adjustment for Changes Relating to Future Service

Occasionally, there may be unfavourable changes relating to future service that happen to be larger than the CSM even after accreting for interest. How should these be accounted for? The logic of IFRS 17 continues.

Principle 4: When an insurer recognises that written business, that was previously expected to be profitable, is now expected to be loss-making, e.g. because of changes relating to future service, it must not be allowed to spread the expected losses for that business over time and instead must recognise those losses immediately. It will do so by first extinguishing the CSM and then establishing a LC in respect of the remaining excess (based on paragraphs 44(c) and 45(c)).

Principle 4 consequently extends the scope of Principle 2 so that it can apply to the measurement of the CSM subsequent reporting periods. Even at subsequent measurement, the insurer is not allowed to establish a negative CSM and defer loss recognition, instead, it must recognise such excess losses immediately.

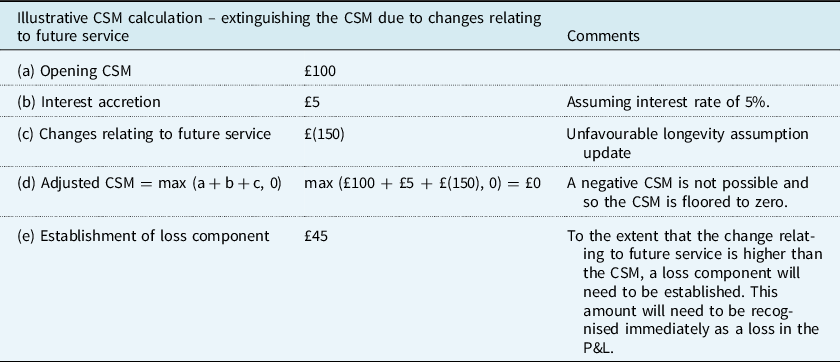

An example is shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Example of CSM Extinguished due to Changes Relating to Future Service

2.1.3. CSM for reinsurance contracts held

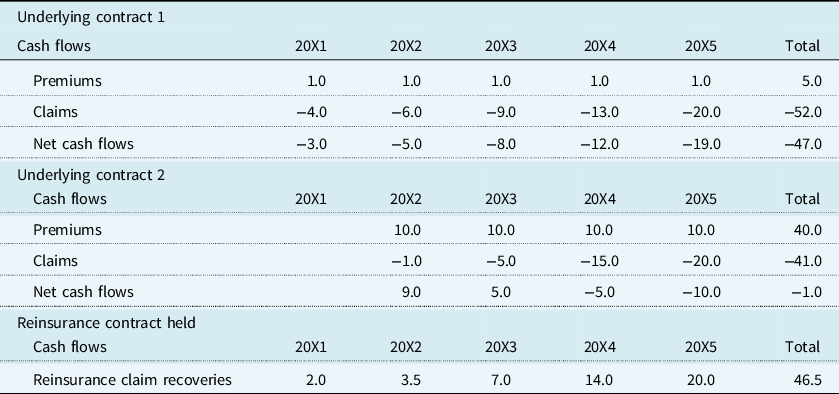

The principles discussed so far apply equally to insurance contracts written by insurers as well as reinsurance contracts written by reinsurers. However, in recognition of the fact that concepts such as unearned profit or onerousness cannot apply to reinsurance contracts held, IFRS 17 modifies some of these principles in important ways to better accommodate such contracts.

Principle 5: With some exceptions (only one of which is deemed important to this introduction – see below), when an insurer (or reinsurer) purchases reinsurance, it must not be allowed to recognise the expected net cost or net gain for that contract immediately, instead, it must spread that net cost or net gain over time (based on paragraph 65).

Principle 5 consequently modifies the logic of Principle 1 to make it appropriate for reinsurance held: when an insurer (or reinsurer) purchases reinsurance, it is forced to avoid the immediate recognition of not only the expected cost of that reinsurance, but also any expected gains. In other words, reinsurance CSM, unlike the gross underlying CSM, has no floor and can have either positive or negative signage. An example of this calculation is shown in Table 6.

Table 6. Example of Reinsurance CSM Calculation at Initial Recognition for Reinsurance Contracts held

The reinsurance CSM can only be recognised in the profit or loss statement on a gradual and systematic basis over time, as and when reinsurance services are received. At any given reporting period, the reinsurance CSM consequently represents the expected amount of costs or gains that have not yet been recognised for the group of reinsurance contracts in question. Just like the gross underlying CSM, the reinsurance CSM also needs to be adjusted for all changes relating to future service (with some exceptions).

One important exception relating to Principle 5 concerns an issue relating to the interaction between gross underlying business and corresponding reinsurance held. Consider an insurer that has just written a loss-making contract and, as per Principle 2, recognises an immediate P&L hit of £35 (say). However, the insurer already holds an external reinsurance contract under which this contract is 100% reinsured on an original terms quota share basis. Principle 5 on its own would imply that a (net gain) reinsurance CSM of £35 would be established and spread over time. However, this results in a timing mismatch: even though gross underlying claims are effectively capitalised and recognised on day 1 in recognising the upfront loss, the corresponding reinsurance recoveries cannot be taken credit for immediately. The exception to Principle 5 is designed to avoid this mismatch from arising.

Exception to Principle 5: If an insurer (or reinsurer) has purchased a reinsurance contract either before, or at the same time as, it recognises a loss for a loss-making underlying contract, the insurer must recognise reinsurance income to offset (in full or in part) the underlying loss recognised. The insurer shall adjust the reinsurance CSM to reflect that credit for future claim recoveries has already been taken by recognising income (based on paragraphs 65 and 66A).

2.1.4. Recognition of the CSM in profit or loss

One final point of detail remains to be covered. Earlier, it was noted that the CSM can only be recognised in the profit or loss statement on a gradual and systematic basis over time, as and when insurance services are provided. Why is this required and what does it mean in practice?

Why is this required?

IFRS 17 Effects Analysis answers this question best:

“Currently, insurers recognise profits inconsistently over time. The timing of recognition of profit for insurance services can vary significantly by jurisdiction and by product. Some insurers recognise profit immediately when an insurance contract is written. Other insurers recognise profit only when the contract terminates. Other insurers recognise profit over the duration of the insurance contract on the basis of the passage of time.” (IFRS 17 Effects Analysis, page 33)

Consider an immediate annuity contract with a single premium paid by the policyholder at the outset of the contract in return for fixed regular annuity payments for the remainder of the policyholder’s life. The insurer that writes this contract expects to make a profit:

-

Recognising all this expected profit upfront creates a large disconnect with the fact that insurance service is likely to be provided over several years to come.

-

Waiting for all this profit to be recognised only when the policyholder dies is problematic because companies would have to wait for several decades before being able to recognise a return on their investments.

-

Recognising this profit systematically over time avoids both extremes and enables the possibility for a reasonable link to be secured between the rate at which profit is recognised and the amount of insurance service provided over time.

What does this mean in practice?

To determine how much profit should be recognised in each period, the entity is required to identify the number of “coverage units”. In effect, coverage units are an attempt to quantify the amount of insurance services provided to groups of contracts. They are determined by considering the “quantity of benefits” provided under contracts and how long on average the contracts are expected to last.

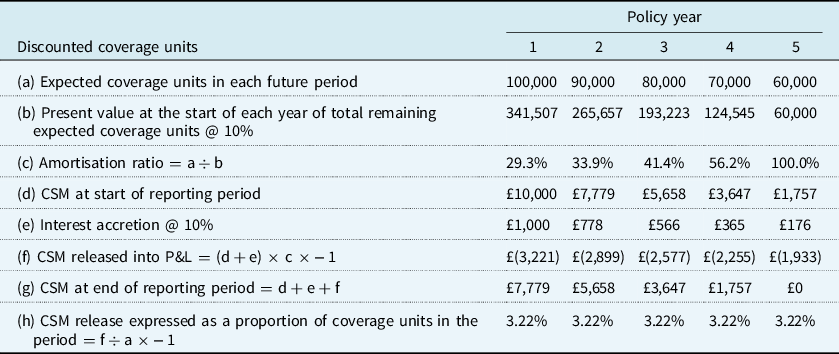

Take a simplified example of a 5-year term assurance contract with a sum assured of £100. The calculations for this example are shown in Table 7.

Table 7. Example of CSM Amortisation Calculations

After allowing for the expected lapse and mortality decrements, the insurer arrives at a view of sum assured that is expected to remain in force for each projection year (see column A). The insurer takes the view that the sum assured in force is an appropriate measure for the quantity of benefits and consequently uses this for its coverage units (see column B). It aggregates total coverage units expected to be provided in all years (see column C). It calculates an “amortisation ratio” by expressing coverage units in the current year as a percentage of total coverage units remaining to be provided (see column D).

Once the amortisation ratio is determined, it is applied to the CSM: the amount by which the CSM is reduced through this amortisation is recognised as profit in the P&L.

An example of the CSM release in profit or loss calculation is shown in Table 8.

Table 8. Example of CSM Recognition Calculation

Coverage units, just like the CSM, need to be reassessed at subsequent periods because of changes relating to future service.

In the fifth and final year of the simplified term assurance contract above, the amortisation rate is 100%. Applying this to the CSM results in a closing CSM of zero indicating that no further service remains to be provided and consequently no unearned profits left to recognise.

This concludes the introduction to the logic of the CSM.

2.2. How is the CSM Calculated?

This paper has briefly touched on how the CSM is calculated in section 2.1 but will now consider this question in this section in more detail.

CSM at initial recognition

For all types of insurance products, the CSM at initial recognition for a group of written contracts is calculated as shown in Table 9.

Table 9. Steps for Calculating the CSM at Initial Recognition

Note in this calculation:

-

The present value computation is based on the appropriate IFRS 17 discount rate. Unlike SII, IFRS 17 does not prescribe discount rates and companies are responsible for determining their own discount rates that, amongst other things, “reflect…the characteristics of the cash flows and the liquidity characteristics of the insurance contracts” (paragraph 36). The setting of discount rates is a substantial topic in its own right, and, apart from some issues immediately relevant to the CSM, is not addressed in much detail in this paper.

-

Cash flows expected in the future should only take account of cash flows that fall within the IFRS 17 contract boundary (paragraph 33). The determination of contract boundaries under IFRS 17 is not always straightforward and cannot be assumed to follow SII contract boundaries – this is explored further in section 4.3.

-

Cash flows at the date of initial recognition include initial premiums as well as directly attributable acquisition cash flows. The date of initial recognition has a specific sense under IFRS 17 (paragraph 25) and there are challenges around determining it – these are addressed in section 3.3.

-

The RA for non-financial risk reflects “uncertainty about the amount and timing of the cash flows that arises from non-financial risk” (paragraph 37). The RA under IFRS 17 has overlapping features with the risk margin under SII however there are important differences. Most notably, unlike SII, the calculation of the RA is not prescribed under IFRS 17 and consequently, it is up to companies to determine for themselves the techniques they will use to calculate the RA. The RA is a substantial topic in its own right, and, with some exceptions, is not addressed in any detail in this paper.

-

The “asset for insurance acquisition cash flows” is a newly introduced concept under IFRS 17. It is important to note this asset is not the same as the DAC (deferred acquisition cost) asset that readers may already be familiar with (e.g. from IFRS 4). The purpose of this new asset is to enable an allocation of incurred acquisition costs to future new business. For many life companies, this new asset will not need to be established (the situation differs for non-life companies) however it is sufficient to note that the allocation and derecognition of the asset heavily relies on judgement. Details of this asset fall outside the scope of this paper and consequently are not discussed any further.

-

The final item that relates to “any other asset or liability previously recognised for cash flows” is also a new concept under IFRS 17. The Standard recognises that there could be cash flows that companies have to record before the recognition of a contract. For example, a premium could be paid before it is due and before the coverage period begins. This item consequently attempts to ensure that such cash flows are not missed from the determination of the CSM. Further details on this asset are not relevant to the CSM and consequently not discussed any further.

CSM at subsequent measurement

Unlike the calculation just covered for the CSM at initial recognition, which can be applied universally to all types of insurance products, different rules apply to the CSM at subsequent measurement depending on the type of product in question. This point reflects a fundamental distinction that IFRS 17 draws between two types of contracts:

-

“Insurance contracts without direct participation features”.

-

“Insurance contracts with direct participation features”.

Examples of contracts without direct participation could include non-profit term assurances, or non-profit whole of life contracts. Examples of contracts with direct participation could include unit-linked (UL) savings business or WP policies.

An important implication of this distinction, which is relevant to the CSM, relates to the different treatment IFRS 17 requires depending on the type of contract. Earlier, the existence of “some exceptions” was noted when describing Principle 3 in section 2.1.2 – the discussion can now make at least one of these explicit.

For contracts without direct participation features, IFRS 17 prohibits the CSM from being adjusted for impacts arising from changes in discount rates and certain kinds of assumptions relating to financial risk. However, there is no such prohibition when adjusting the CSM for contracts with direct participating features.

To state it more simply: IFRS 17 has two different measurement models for the two types of contracts noted above. These two models are referred to in the industry as the “general measurement model” (GMM) and the “variable fee approach” (VFA).Footnote 6

The existence of two measurement models implies that the CSM at subsequent measurement can diverge drastically over time. Since this can have a material impact on the amounts and timing of profit recognition, the paper dedicates section 4.2 to identify the challenges that arise in deciding which measurement model will apply – using the VFA is not simply a matter of choice for companies, instead IFRS 17 describes the eligibility criteria that must be met to qualify for the VFA.

For the purposes of an introduction, the description above is deemed sufficient. Those interested in the actual calculations required to determine the CSM at subsequent measurement may refer to section 4.5.1.

3. Level of Aggregation and Recognition

3.1. Introduction

Section 3 provides a high-level overview of issues that arise within the themes of level of aggregation and recognition (spanning paragraphs 14–28 F and B36–B119F).

3.2. Level of Aggregation

3.2.1. Overview

This section very briefly looks at considerations around the setting of the level of aggregation.Footnote 7 Note that the discussion here focuses on direct contracts written and not reinsurance contracts held (for which the requirements are different and covered in 4.8.3). Additional considerations apply in the context of WP business – these are discussed in 4.9.2.

A fundamental principle of IFRS 17 is that the CSM needs to be calculated and tracked at the level of granularity of “groups of contracts”. The level of aggregation requirements (paragraphs 14–24) describe how these groups of contracts are to be arrived at.

First, an entity needs to identify portfolios of insurance contracts subject to similar risks and managed together (paragraph 14). Then, those portfolios must be split into further groups based on their profitability (paragraph 16). Finally, those groups must be subdivided into further groups such that no group contains contracts issued more than 1 year apart (paragraph 22). Further subdivisions beyond these basic requirements are permitted (paragraph 21). Groups can comprise of a single contract if that is the result of applying these requirements (paragraph 23).

Figure 2 illustrates what is at stake when setting levels of aggregation – ultimately, an entity needs to strike a balance between the proposed granularity and its operational practicability.

Figure 2. Impacts to consider when setting the level of aggregation.

3.2.2. Identifying portfolios

As noted earlier, the requirement is that a portfolio of contracts, subject to similar risks and managed together, needs to be identified. How might this be done?

“Similar risks”

There is limited guidance in IFRS 17 as to how an entity should interpret “similar risks”. This leaves room for judgement because many insurance contracts typically tend to expose companies to more than one type of risk (e.g. accelerated CI policies contain both mortality and morbidity risks). Further, the overall risk profile of products may vary over the lifetime of a contract, such as WP policies with guaranteed annuity options (GAOs).

One possible way to define “similar risks” is by identifying the dominating risk(s) between products that are common and non-offsetting and respond similarly to changes in key assumptions. This prevents entities from grouping, say, individual protection and immediate annuity contracts together, but allows, say, level term and decreasing term contracts to be grouped together (though other considerations will still apply).

A challenge with this is how to effectively measure those identified dominating risks. One way is to leverage information from RA calculations. However, this could be deficient as the RA is only in relation to non-financial risks. This means that entities may have to consider other internal or external measures of risks to support this classification, e.g. those under Solvency II or other economic views that take both insurance and financial risks into account.

“Managed together”

As with “similar risks”, there is limited guidance on how to interpret whether contracts are “managed together”. Here are a few considerations that could be used:

-

Do the contracts sit on the same administrative system?

-

Do the contracts have the same distribution channel?

-

Do all products in a group follow the same asset–liability management process?

-

Are the underlying assumptions the same across all products?

-

How are the contracts presented in management information (MI) packs?

3.2.3. Dividing portfolios into profitability groups

Paragraph 16 requires entities to divide a portfolio of insurance contracts issued into a minimum of three groups of contracts:

-

Loss-making contracts (if any).

-

Contacts without significant risk of becoming onerous subsequently (if any).

-

all remaining contacts (if any).

Note, for the avoidance of doubt, that once a contract has been placed into a group, it stays in that group until termination or modification and the entity does not need to assess whether the grouping needs to change.

Assessing the likelihood of a contract becoming onerous subsequently could be a challenging task. One possibility is to perform scenario tests or sensitivity analyses. However, judgement will need to be applied as to how to interpret “significant risk” and calibrate this appropriately. If an entity’s threshold is an extreme stress corresponding to the 99.5th percentile, the majority of contracts could be at significant risk of becoming onerous!

An entity should consider the cost/benefit trade-off associated with the granularity of groups. There may be favourable implications in the P&L by grouping very profitable contracts separately from moderately profitable contracts. However, this has the downside in the form of additional operational complexity, including the need to track CSMs, locked-in assumptions, and the reduced ability to “absorb” unfavourable changes relating to future service in groups with lower CSMs.

3.2.4. Further reading

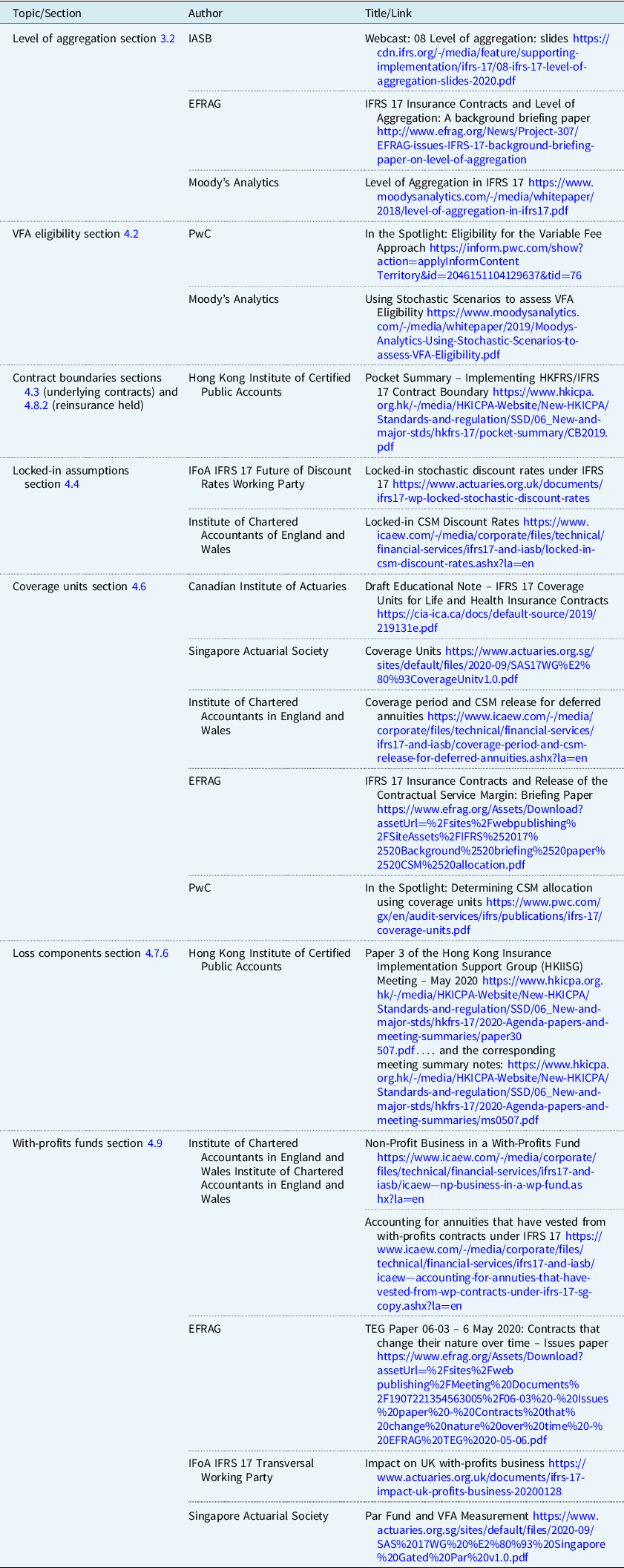

This section summarises some of the challenges relating to the aggregation and outlines considerations an entity could make when implementing the Standard. Readers further interested in the rationale behind the IFRS 17 aggregation requirements and more detailed surveys of its implications may find the following documents useful to consult:

-

IASB Webcast: 08 Level of aggregation: slides

-

EFRAG: IFRS 17 Insurance Contracts and Level of Aggregation: A background briefing paper

-

Moody’s Analytics: Level of Aggregation in IFRS 17

https://www.moodysanalytics.com/-/media/whitepaper/2018/level-of-aggregation-in-ifrs17.pdf.

3.3. The Date of Initial Recognition

This section discusses the determination of the date at which a group of new contracts should be initially recognised. Note that the discussion here focuses on direct contracts written and not reinsurance contracts held (for which the requirements are slightly different and covered in 4.8.2).

Paragraph 25 requires that a group of insurance contracts issued should be recognised from the earliest of three dates:

-

(a) The beginning of the coverage period of the group of contracts.

-

(b) The date when the first payment from a policyholder in the group becomes due.

-

(c) For a group of onerous contracts, the date when the group becomes onerous.

Under IFRS 17, “coverage period” is a defined term, which refers to “the period during which the entity provides insurance contract services” (see Appendix A of IFRS 17). Therefore, in assessing the date in (a), consideration needs to be given to the IFRS 17 coverage period. As noted below, this may present a challenge when compared to the requirements of SII.

The interpretation of (b) is relatively clear, particularly given the clarification in paragraph 26 that, where there is no contractual due date, the first payment is deemed to be due when it is received.

In some instances, the date in (c) could be difficult to ascertain practically. For example, policy administration systems do not always have an embedded link to pricing models – consequently existing processes may not be able to immediately identify when a loss-making policy has been written.

One challenge to be aware of is that the requirement in (a), whilst similar, is subtly different to SII, which requires contracts to be recognised at the earliest of either the date coverage begins or the date the entity becomes a party to the contract. Whilst in most scenarios, the recognition date is expected to be the same under IFRS 17 and SII, there may be scenarios where small differences may arise. This is likely to give rise to operational challenges.

Example 3.1: A bulk annuity contract is signed on 1 January, the premium is due on 1 February and the “coverage” starts on 1 February (in this example, it has been assumed the IFRS 17 coverage period start date and the SII coverage start date are the same). Under this example, the IFRS 17 recognition date would be 1 February but the SII recognition date would be 1 January.

If such differences arise, entities may want to explore options to avoid such recognition date discrepancies in their different bases. For example, they may explore the materiality of any date differences or whether processes can be put in place to avoid date discrepancies arising for future new business.

Once an entity has determined the recognition date for a group of contracts, they will need to work through practical considerations. For example, determining the recognition date is one thing, but determining the point at which a contract is recognised in the actuarial cash flow models is another. This latter, practical point may have implications for the locked-in discount rate, the appropriate non-economic assumptions to use for recognising the CSM at initial recognition, and, how much (if any) CSM will be released as profit for the month (assuming monthly reporting). The Standard is silent on this issue, however, in line with current industry practice under SII and IFRS 4, the working party expects that some approximations will be acceptable, although these will need to be discussed with auditors. There appear to be four choices for the date of recognition in actuarial cash flow models:

-

1. The actual recognition date.

-

2. The start of the period.

-

3. The end of the period.

-

4. An “average” point in the period, e.g. the middle of a month for all contracts written in that month.

In deciding between these options, an entity should consider a number of factors, e.g.:

-

Operational considerations – what approach is currently used in the actuarial models? If recognition of new business written is currently based on, say, the start of the month, then there may be some significant model development required to change to, say, an end of month approach.

-

Commercial considerations – the sensitivity of the results to, e.g. interest rate changes, and the materiality of the new business volumes should be considered. For example, for a high materiality product line with high interest rate sensitivity, an entity may choose to use a more “accurate” approach to try to align the locked-in discount rate as closely as possible to that used in pricing.

-

Complexity of calculation – more complex approaches, e.g. the actual date or average date may introduce more complexity into calculations, requiring more effort to validate and explain to users. In contrast, an end of month approach will result in no interest accretion or CSM release in the month of new business being written, which may simplify the validation process but reduce comparability with peers.

Conclusion

An entity will have a number of decisions to make in determining the appropriate point at which to recognise the new business. In making these judgements, an entity should consider the balance between operational impacts, commercial implications and the complexity introduced to the calculations and therefore the results.

4. Measurement

4.1. Introduction

Section 4 is the core of this paper. The material presented here focuses on issues that arise within the theme of measurement (spanning paragraphs 29–71 and B36–B119F).

4.2. VFA eligibility

4.2.1. The three measurement models

IFRS 17 introduces three possible measurement models: the general measurement model (GMM), the variable fee approach (VFA) and the PAA.

-

GMM is the “default” measurement model for insurance contracts and will be used to measure contracts without direct participating features or products that fail to meet the VFA or PAA eligibility requirements.

-

VFA is mandatory to use for contracts with direct participation features that meet the specific VFA eligibility requirements. For contracts with direct participation features that do not meet these eligibility requirements, VFA cannot be applied and instead the GMM will need to be used.

-

PAA is intended as a simpler alternative for contracts that have a coverage period of 1 year or less, but in practice, it can also be used for contracts with longer coverage periods upon meeting additional criteria.

A CSM is only calculated under the GMM and VFA; there is no concept of a CSM under the PAA.

At initial recognition of a contract, the calculation of the CSM through either the GMM or the VFA will lead to the same result. However, on subsequent measurement, VFA requires the CSM to be updated for more changes than permissible under the GMM – e.g. the impact of changes in discount rates and other financial items must adjust the VFA CSM but cannot adjust the GMM CSM.

Beyond just the financial implications of using different models (in terms of the development of the CSM on an ongoing basis), there are important technical and operational implications that follow. For example, having to use the GMM for participating contracts that fall short of VFA eligibility implies the need to lock-in to financial assumptions; technical challenges arise in how to interpret the requirements and operational challenges arise in having to build the systems to accommodate these requirements.

Section 4.2.2 highlights some of the criteria that must be met for contracts to be measured under the VFA. Failure to meet these criteria results in the contracts having to be measured under the GMM which results in companies having to address the kinds of issues illustrated in the paragraph above.

4.2.2. VFA eligibility

The VFA is the measurement model mandated for contracts with direct participation features that meet the specific VFA eligibility requirements. These are insurance contracts that are substantially investment-related service contracts under which an entity promises an investment return based on underlying items. To be classified as VFA-eligible, a contract must meet the following criteria as set by paragraph B101:

-

the contractual terms specify that the policyholder participates in a share of a clearly identified pool of underlying items;

-

the entity expects to pay to the policyholder an amount equal to a substantial share of the fair value returns on the underlying items;

-

the entity expects a substantial proportion of any change in the amounts to be paid to the policyholder to vary with the change in fair value of the underlying items.

It is important to note, as per paragraph B102, that the classification is set at inception of the contract and is not changed thereafter (unless the contract is modified).

The need for contractual linkage (i.e. the need for a clearly identified pool to be contractually specified) is a crucial aspect of the eligibility requirements:

-

In the UK, in the case of UL insurance or WP contracts, contractual linkage could exist by way of policy terms or PPFM, respectively.

-

However, for many contracts outside of the UK, this requirement cannot be met. For example, there are contracts in Europe and India where the benefit payable to the policyholder includes the sum assured as well as regular additions based on the returns on underlying assets. However, the contractual terms do not clearly identify the pool of underlying assets on which these regular additions will be based on, instead, the contracts specify that any additions are at the discretion of the entity.

Concerning the notions of “substantial share” and “substantial proportion of any change”, paragraph B107 provides some guidance but leaves room for interpretation. In terms of implementation, entities will have to devise their own tests to see whether payouts can be deemed substantial. For example, one possible interpretation (but not without problems) is that, at policy inception, the insurer estimates the PV of investment income as a percentage of the PV of cash outflows. If this ratio is higher than a certain percentage, then it can be interpreted as a substantial share of payouts comprising of returns on underlying items

Here are some examples of contract features to illustrate when VFA is likely to be applied:

-

UL insurance:

Usually, the most straightforward case of VFA eligibility applies to UL insurance contracts: premiums are invested in an investment fund on behalf of the policyholder and the payout to the policyholder is directly linked to the performance of the underlying fund.

-

Minimum return guarantees:

Paragraph B108 addresses contracts that offer minimum investment-return guarantees to policyholders (e.g. a guaranteed minimum return of 4% per annum). Such contracts raise some challenges for VFA eligibility. In some stochastic scenarios, payouts will clearly vary with the changes in the fair value of the underlying items because the return on the investment fund exceeds the guaranteed return. In other scenarios, the payouts will not vary with the changes in the fair value of the underlying items because the guaranteed return exceeds the investment fund performance. If the stochastic scenarios suggest that the guaranteed return bites in more cases than not, the contract is unlikely to meet the second and third conditions of paragraph B101 and will not qualify for VFA measurement.

It is important to note that this does not automatically mean that contracts with high minimum return guarantees will not be VFA eligible simply because guarantees are likely to bite in our current low-interest rate environment. Unless deemed impracticable for the purposes of transition, this assessment is to be performed based on expectations that prevailed when these contracts were written – assuming the guarantees were accurately costed and charged for, and the contracts were expected to be profitable, these could still qualify for VFA measurement.

-

Payouts linked to indices:

Under some contracts, payouts to the policyholders are linked to a benchmark index, such as the yield on a basket of government bonds; a stock index; or a specified subset of the net assets of the insurer. As long as these indices are contractually clearly identified, contracts that depend on them will likely qualify for VFA measurement: indeed, IFRS 17 is explicit that insurers need not hold the identified pool of underlying items.

-

Management discretion:

The mere existence of management discretion to vary the amounts paid to policyholders does not automatically result in VFA ineligibility. However, the link to the underlying items must be enforceable. Sometimes, groups of contracts participate in the same “general account” pool of assets, but there is significant management discretion on how to allocate the fair value return of the asset pool over the different groups of contracts participating in the pool. Such an approach weakens the link to the underlying items, and hence the possibility for using the VFA.

4.2.3. Further reading

As this section indicates, assessing VFA eligibility will not always be a straightforward exercise. There is room for interpretation and the assessment will require significant judgement. Readers may consequently find the following documents useful to consult as well:

-

PwC: In the Spotlight – Eligibility for the Variable Fee Approach

https://inform.pwc.com/show?action=applyInformContentTerritory&id=2046151104129637&tid=76.

-

Moody’s Analytics: Using Stochastic Scenarios to assess VFA Eligibility

4.3. Contract Boundaries

4.3.1. Introduction

The CSM can only take into account cash flows that fall within the IFRS 17 contract boundary. This makes it a topic of significance for this paper. Many actuaries are familiar with the concept of contract boundaries from Solvency II, but, as with other overlapping concepts between Solvency II and IFRS 17, there are differences in the details. This section explores some of these differences, as well as identifying product features, which may require judgement to determine the appropriate contract boundary under IFRS 17.

The section only covers contract boundaries in the context of insurance contracts written. See 4.8.2 for a discussion relevant to reinsurance contracts held.

4.3.2. IFRS 17 versus Solvency II

Paragraph 34 of IFRS 17 defines the contract boundary as follows:

“Cash flows are within the boundary of an insurance contract if they arise from substantive rights and obligations that exist during the reporting period in which the entity can compel the policyholder to pay the premiums or in which the entity has a substantive obligation to provide the policyholder with insurance contract services (see paragraphs B61–B71). A substantive obligation to provide insurance contract services ends when:

-

(a) The entity has the practical ability to reassess the risks of the particular policyholder and, as a result, can set a price or level of benefits that fully reflects those risks; or

-

(b) Both of the following criteria are satisfied:

-

i. the entity has the practical ability to reassess the risks of the portfolio of insurance contracts that contains the contract and, as a result, can set a price or level of benefits that fully reflects the risk of that portfolio; and

-

ii. the pricing of the premiums up to the date when the risks are reassessed does not take into account the risks that relate to periods after the reassessment date.”

-

This definition seems to start from the premise that any possible future cash flows are inside the contract boundary unless an entity can demonstrate that it meets the strict criteria (in (a) and (b) above) that the obligation ends – this suggests a high bar needs to be met to exclude cash flows from the contract boundary.

In contrast, under a common interpretation of the Solvency II definition (see 4.3.6), the burden of proof is on the entity to justify that cash flows are inside the contract boundary, particularly for UL business.

As a result of these differences, even though for many products/features the contract boundary will be the same for Solvency II and IFRS 17, there is potential for longer contract boundaries under IFRS 17, i.e. some cash flows that are outside the contract boundary for Solvency II, maybe inside the contract boundary for IFRS 17.

Some examples of when this may occur are discussed below.

4.3.3. Example 4.1: unit-linked regular premium workplace pensions

To demonstrate some of the judgements that need to be made, and potential divergences from Solvency II, consider a UL regular premium workplace pension. It should be noted that the assessment of contract boundaries will depend on the specific details of the products, consequently different conclusions could be drawn from those in this example.

Future regular premiums

The first key question for contract boundaries for (UL regular premium business is whether the future regular premiums are inside the contract boundary. Under Solvency II, future regular premiums are generally outside the contract boundary unless the entity can compel the policyholder to pay the premiums or there is an economically significant guarantee or death benefit. Unlike Solvency II, the IFRS 17 definition of contract boundaries does not differentiate explicitly between cash flows relating to paid and future premiums and consequently, this should be assessed against the standard contract boundary requirements:

-

Substantive rights and obligations: Whilst an entity does not have a substantive right to make policyholders pay future regular premiums, if premiums are paid then the entity likely has a substantive obligation to provide services related to those premiums.Footnote 8 Therefore, unless future regular premiums fall within the scope of the IFRS 17 criteria for determining when a substantive obligation ends, it can be concluded that these future regular premiums, and the cash flows related to them, should be within the contract boundary.

IFRS 17 criteria for determining when a substantive obligation ends:

-

○ Practical ability to reassess risks at policyholder level: UL product pricing tends to be done at the fund level, and hence limited practical ability to reprice at policyholder level.

-

○ Practical ability to reassess risks at portfolio level: this will depend on specifics of the product terms and conditions (T&Cs) and administrative options and is, therefore, likely to vary by product and entity. This should also take into consideration any contractual charge caps applying.

-

○ Risks related to future cash flows not being included in the pricing of premiums to date: this could vary by entity and product, but it is a common practise to allow for future regular premiums in initial pricing, and hence this condition is unlikely to be met.

-

Conclusion: Future regular premiums are likely to be inside the IFRS 17 contract boundary based on information contained in this example.

Increments

Having concluded that future regular premiums are inside the contract boundary, it now remains to be considered whether future increases/decreases to those regular premiums should be inside the contract boundary, as well as other future premiums (single premium increments such as transfers in from another pension scheme). The drivers of increments into workplace pension schemes will vary, and could include salary increases, auto-enrolment step ups and marketing campaigns to encourage transfers or pension savings. The contract boundary assessment could differ for these, but entities will need to keep an eye on the practicability of applying any assessment.

Considering increments against the IFRS 17 contract boundary assessment criteria:

-

Substantive rights and obligations: as for regular premiums, entities do not have a substantive right to make policyholders pay increments. The question is, therefore, whether the entity has a substantive obligation to accept if a policyholder wishes to increment their existing policy. This will require an assessment of the T&Cs to consider under what circumstances the entity can refuse or stop accepting increments. This may vary by product and by entity. Entities should also consider whether the policyholder expectations at the point of sale (that the product will meet their financial needs) could create a substantive obligation (noting that the Standard does not say “contractual right or obligation”). Typically for pension accumulation products, it could be argued that the ability to change premiums as policyholder circumstances (e.g. their salary) changes is fundamental to the contract meeting the policyholder’s financial needs and potentially creates a substantive obligation to accept future premium increases, irrespective of the T&Cs.

-

IFRS 17 criteria for determining when a substantive obligation ends:

-

○ Practical ability to reassess risks at policyholder level: as above, there will be generally limited practical ability to reprice at the policyholder level.

-

○ Practical ability to reassess risks at portfolio level: as above, this will vary by product and entity.

-

○ Risks related to future cash flows not being included in the pricing of premiums to date: this could vary by entity and product, but it is not uncommon to allow for future increments in pricing.

-

Conclusion: This will need careful consideration of the specifics of the product including how it is priced and administered. However, there is a reasonable possibility that some or all future increments to UL contracts will be inside the IFRS 17 contract boundary.

Implications

First, consider the impact on the CSM if the above cash flows are inside or outside the IFRS 17 contract boundary.

-

Regular premiums and increments are inside the contract boundary:

-

○ Initial recognition: the CSM will be based on projected cash inflows and outflows which include best estimate expectations of the size and timings of future regular premiums and increments.

-

○ Subsequent recognition: as regular premiums and increments are received these will be included in the measurement of the CSM group of the original contract. Experience variances between the received and expected premiums/increments will arise. If these relate to future service, they will adjust the CSM.

-

-

Increments are outside the contract boundary:

-

○ Initial recognition: the CSM calculation will not include projected cash inflows or outflows resulting from future increments.

-

○ Subsequent recognition: as increments are received, these should be recognised as new contracts, put into the relevant open cohort group at the time the increment is received and a new CSM recognised.

-

As a result of the above impacts, there could be a number of operational and commercial implications, e.g.

-

SII differences:

-

○ There is a high likelihood of different contract boundaries between SII and IFRS 17 for UL business.

-

-

Operational:

-

○ Changes to contract boundaries from IFRS 4/SII will likely require developments to actuarial models.

-

○ If the conclusion is that some, but not all, types of increments are inside the contract boundary, data will be required to enable increments to be allocated between those inside and outside the contract boundary – this data may not exist.

-

○ If additional cash flows are inside the contract boundary then:

-

New demographic assumptions may be needed, e.g. paid-up rates and/or level of increments. These assumptions are likely to be highly judgemental and potentially material.

-

Additional experience variance analysis of the differences between expected and actual cash flows may be needed to correctly calculate the CSM at subsequent recognition.

-

-

○ If certain cash flows are not inside the contract boundary then:

-

Future premiums/increments will need to be isolated from the original contract for inclusion in the appropriate CSM group. Separating policies in this way could give rise to data and modelling challenges.

-

-

-

Commercial:

-

○ If some increments are moved inside the contract boundary then this will change when new business is recognised and hence new business premium key performance indicators (KPIs) will be impacted. This change will need to be carefully managed internally and externally.

-

○ The Standard requirements will potentially result in contract boundaries more in line with pricing assumptions. This may reduce the risk of recognising loss-making contracts.

-

4.3.4. Example 4.2: term assurance with reviewable premiums

Now consider a further example of a term assurance contract with premiums that are reviewable every 5 years. In this example, the key question is whether there is a contract boundary at the premium review date. Again, the answer will depend on the specifics of the product, so instead of giving an explicit answer, this section lays out some of the points to consider in this scenario.

In analysing the ability to reassess the risks, both at individual and portfolio level, it is worth noting the February 2018 Transition Research Group (TRG) discussionFootnote 9 clarifying that the “risk” here should be interpreted as policyholder risks (e.g. mortality risks).

As in the previous example, this is assessed against the contract boundary requirements:

-

Substantive rights and obligations: the point here is whether the entity has a substantive obligation to provide cover beyond the review point, i.e. could the company cancel the contract at that point? If so, it potentially does not have a substantive obligation. If not, a substantive obligation exists.

-

IFRS 17 criteria for determining when a substantive obligation ends:

-

○ Practical ability to reassess risks at policyholder level: given the TRG interpretation of risk above, whether this criterion is met will primarily depend on whether the entity re-underwrites the individual at the review point. If full underwriting is carried out and the entity has the practical ability to charge a price based on this updated information, then this criterion is clearly met, resulting in a contract boundary at this point. If partial underwriting is done (e.g. only asking for updated smoker status) then judgement will be needed to assess whether the entity can materially reassess risks at the policyholder level. If not met, the last two criteria should be looked at.

-

○ Practical ability to reassess risks at portfolio level: as above, given the TRG interpretation of risk, if the reviewed premium rates are based on updated mortality assumptions risks then are reassessed at the portfolio level.

-

○ However, for both of the above criteria, it will also need to be considered whether a “practical ability” exists. This goes beyond what the T&Cs allow and considers what an entity would actually do at a review date. This assessment will require judgement. Considerations in making this judgement may include whether the systems are in place to apply premium reviews and the entity’s past performance with respect to premium reviews. For example, if the product T&Cs allow the company to fully underwrite at the premium review date but this has never been done then it may be hard to argue that the company has the practical ability to do so.

-

○ Risks related to future cash flows not being included in the pricing of premiums to date: if the above criterion is met, this final requirement will need to be considered. This asks if the post-review date risks are included in pricing of the original premiums. “Risk” here is again interpreted as policyholder risks, i.e. mortality risk for a protection product.

-

Conclusion: it is a high barrier to meet to have a contract boundary for this type of business, and therefore there is a reasonable chance that post-review date cash flows will be inside the contract boundary. However, this will depend on the specific details of the product and how it is priced and administered and will require judgement to be applied.

Implications

Considering the implications for the CSM of whether there is a contract boundary at the review point or not:

-

Contract boundary: the fulfilment cash flows, and hence the CSM, will be based only on cash flows up to the review point, and the CSM will be released over the coverage period up to that date. If the policy continues after the review point, a new contract will need to be recognised and a new CSM established. If the review point is 12 months, or less, from the recognition point then the contract would qualify for the simpler PAA, although this is optional to apply. Consideration will need to be given to whether some of the acquisition costs will need to be deferred and allocated to the renewing contract.

-

No contract boundary: the cash flows beyond the review date will be included in the fulfilment cash flows and hence CSM. This CSM will be released over the full coverage period, up to the end of the contract term.

As a result of the above impacts, there could be a number of operational and commercial implications, e.g.:

-

SII differences:

-

○ The SII contract boundaries for such products differ across the market, depending on the specifics of the products, however, differences could arise.

-

-

Operational:

-

○ If additional cash flows are inside the contract boundary then:

-

New demographic assumptions may be needed, e.g. proportion of contracts that lapse at the review point.

-

-

○ If certain cash flows are not inside the contract boundary then:

-

Contracts will need to be moved into new CSM groups at the review point. Data on review dates may not be readily available in existing data extracts and this could give rise to data and modelling challenges.

-

-

○ A DAC asset may need to be set up and managed (i.e. for a proportion of the acquisition costs to the contracts recognised post-review point).

-

-

Commercial:

-

○ A change to the contract boundary compared to IFRS 4 would result in a change in when new business written is recognised, and hence the timing of new business value metrics would be affected.

-

4.3.5. Conclusion

The IFRS 17 contract boundary requirements differ from the SII requirements and therefore could result in entities having different contract boundaries for some products between the two metrics. Determining the contract boundaries under IFRS 17 will require significant judgement, taking into consideration a number of factors, including:

-

Features and T&Cs of products.

-

Any implied substantive obligations/rights arising from the features of the product or policyholder needs it is meeting.

-

Pricing practices.

-

Administrative practices.

Changes to contract boundaries could have far-reaching operational and commercial implications that will need careful consideration.

4.3.6. Solvency II reference texts

Extracts of the key text of the Solvency II contract boundary regulations are given below for reference (source: Solvency II Delegated Regulations 2015/35, Article 18 “Boundary of an insurance or reinsurance contract”, paragraphs 2, 3 and 5):

Extract of Paragraph 2: All obligations relating to the contract, including obligations relating to unilateral rights…to renew or extend the scope of the contract and obligations that relate to paid premiums, shall belong to the contract unless otherwise stated in paragraphs 3 to 6.

Extract of Paragraph 3: Obligations which relate to… cover provided… after any of the following dates do not belong to the contract, unless the undertaking can compel the policyholder to pay the premium for those obligations:

-

(a) The future date where the insurance…undertaking has a unilateral right to terminate the contract;

-

(b) The future date where the insurance…undertaking has a unilateral right to reject premiums payable under the contract;

-

(c) The future date where the insurance…undertaking has a unilateral right to amend the premiums or the benefits payable under the contract in such a way that the premiums fully reflect the risks.

Extract of Paragraph 5: Obligations that do not relate to premiums, which have already been paid do not belong to an insurance or reinsurance contract, unless the undertaking can compel the policyholder to pay the future premium, and where all of the following requirements are met:

-

(a) the contract does not provide compensation for a specified uncertain event that adversely affects the insured person;

-

(b) the contract does not include a financial guarantee of benefits

4.3.7. Further reading

For an excellent guide that considers further nuances of contract boundaries under IFRS 17, see:

-

Hong Kong Institute of Certified Public Accounts: Pocket Summary – Implementing HKFRS/IFRS 17 Contract Boundary

4.4. Locked-in Assumptions

4.4.1. What assumptions are locked in and what are the impacts of locking in?

Introduction

This section considers which assumptions are “locked in” when calculating subsequent measurements of the CSM under the GMM, where “locked in” refers to assumptions that don’t change from those at initial recognition. As might be expected, the discussion is only relevant to measurement under the GMM. As outlined below, it is clear that changes in financial risk should not adjust the CSM. However, it is less clear which assumptions should be used when unlocking the CSM for changes in non-financial assumptions (e.g. one large uncertainty being inflation).

This section considers examples of locked-in assumptions for non-participating business. Sections 4.5.3 and 4.9.5 consider locked-in assumptions for participating business that is valued using the GMM (i.e. is ineligible for the VFA).

IFRS 17 references

Paragraph B97 states that an entity shall not adjust the CSM for a group of insurance contracts without direct participation features for changes in fulfilment cash flows due to the effect of changes in the time value of money and financial risk.

Paragraph 87 states that changes in the value of the insurance contract due to changes in the time value of money and financial risk should be captured within insurance finance income or expense. Effectively, this means the impact from financial risk changes will be recognised immediately in the P&L, (and potentially offset by impacts on the assets if perfectly matched) instead of an adjustment to the CSM.

IFRS 17 Appendix A describes a financial risk as the “risk of a possible future change in one or more of a specified interest rate, financial instrument price, commodity price, currency exchange rate, index of prices or rates, credit rating or credit index”.

Paragraph B128 states that “assumptions about inflation based on an index of prices or rates” are financial risks. Where an assumption about inflation is based on “the entity’s expectation of specific price changes” this is not a financial risk.

AP02 April 2019 TRG meeting gives more clarity that cash flows that an entity expects to increase with an index are considered to be an assumption that relates to financial risks, even if they are not contractually linked to a specified index.

Possible interpretations

Interest rates are clearly a financial assumption and they should be locked in for subsequent CSM calculations (as explicitly stated in paragraph B96). However, it is less clear what other financial assumptions are locked in.

There are three possible interpretations covered in this paper however the Working Party is aware that other interpretations exist

-

1. Only discount rates are locked in.

-

2. All financial risks are locked in from inception.

-

3. Only prospective financial risks are locked in, i.e. historical financial risks allow for actual experience.

Interpretation (1) is less likely to be adopted and it is easy to see why this may not always be appropriate with the help of an example:

-

Assume that the impact of a change in longevity assumptions measured using locked-in financial assumptions (and locked-in discount rates) is 100 but that this impact becomes 110 when measured using current financial assumptions, e.g. future expected inflation (but still locked-in discount rates).

-

The difference of 10 represents the change in financial risk, which would not be expected to be included in the adjustment to the CSM under the GMM. Consequently, contrary to interpretation 1, it would be expected to use 100 to adjust the CSM, i.e. locking in all financial assumptions and not just the discount rates in order to capture the appropriate impact of the change in longevity assumptions.

To evaluate interpretations 2 and 3, the discussion will use inflation as an example. First, it should be considered which types of inflation are classified as financial risks. Some interpretation via examples are provided:

-

Consider an annuity contract where the benefit has an explicit, contractual link to CPI then the annuity benefit inflation would be a financial risk.

-

In contrast, consider expense inflation that for simplicity may be expected to increase in line with earnings inflation. Whilst earnings inflation is not contractually linked to CPI, this index is used as a suitable proxy for expected growth, and hence expense inflation would be classified as a financial risk.

-

Consider an insurance contract that includes specific health benefits; the expected increase in the costs of those treatments are specific, e.g. cost of dental care, and are not linked to an index. Therefore, the assumptions would not be financial.

If a company’s assessment is that the inflation assumption is that it is non-financial, then changes in the inflation assumption should adjust the CSM and rates are not locked in.

If the inflation assumption is considered to be financial, using the definition of financial risks from IFRS 17 Appendix A, it is clear that the assumption about future inflation should be locked into prevent second-order changes to the CSM from financial risks. However, at the date of subsequent measurement, it remains unclear in the Standard whether inflation-linked benefits are adjusted for actual historic inflation to date.

For example, at inception, future inflation may have been set at 5% for 5 years. However, after year 3, it is known that actual inflation has been 3% in the first 3 years. For subsequent CSM measurements at the end of year 3, should the 5-year inflation-linked cash flows be adjusted for circa 28% (5% accumulated for 5 years) or 20% (3% accumulated for 3 years and 5% accumulated for 2 years) inflation?

The Standard is silent on this point, but one interpretation is that the latter, i.e. adjusted for historic actual inflation, might be more appropriate since this would not introduce any P&L volatility for a hypothetically perfectly matched insurance contract. For example, suppose after year 3, after allowing for actual inflation, the current PV of fulfilment cash flows is 100, compared to 150 if historic inflation was locked in. Inflation is perfectly hedged, so economically there is no profit or loss. Suppose now that there is a change in non-financial assumptions that increase reserves by 10%. If historic inflation is not locked in, this would increase the CSM by 10. If it was locked-in, it would increase the CSM by 15, with an adjustment of 5 going to insurance finance and expense line directly in the P&L.

In conclusion, financial risks relating to future assumptions and changes in financial risks on the carrying value of the insurance contract do not adjust the CSM and are recognised immediately in the P&L. This means that assumptions about future financial assumptions are locked in at subsequent CSM calculations, however, it remains unclear whether the impact of historic actual changes in financial assumptions (e.g. for inflation-linked liabilities) are locked-in (interpretation 2) or not (interpretation 3). The April TRG papers have provided more clarity in the definition of financial risks, which include inflation when linked to (contractually or not) an index. However, expectations of specific price changes are not considered financial risks and insurers will need to set out a clear definition of a “financial risk” variable and will need to assess whether each assumption meets these criteria.

4.4.2. Using weightings to calculate locked-in discount rates

This section considers the discount rate at initial recognition (or “locked-in discount rate”) for GMM business – how it might be determined and the potential impacts of selecting a suitable alternative.

IFRS 17 paragraphs 36 and B72–B85 outline the principles for calculating the discount rate and when it should be used. In brief, the discount rate should be market consistent, reflect the timing, currency and liquidity of the underlying liabilities and should allow for credit risk (excluding the own credit risk that is specific to the entity).

For insurance and reinsurance contracts valued using the GMM approach, the locked-in discount rate is used to accrete interest on the CSM and to measure changes to the CSM for changes in estimates of fulfilment cash flows for non-financial assumption changes. At the same time, current discount rates will be used to calculate the PVFCF shown on the balance sheet.

Paragraph B73 states that this discount rate may represent the weighted average discount rate over the period that the group of contracts is issued, which is limited to be no longer than 1 year apart. However, a common interpretation is that this is just an option and IFRS 17 does not require a weighted average to be used.

In the simplest case, there may be one contract recognition date for the group of contracts, e.g. for bulk annuity contracts. In this case, setting the locked-in discount rate equal to the discount rate at the point of sale or start of the month (in line with potential cash flow modelling) are suitable options. In this case, as there is no other new business in the year, there is only one discount rate curve used to calculate the CSM and by default will equal the locked-in discount rate.

In other, more common cases, new contracts may be included in a group of contracts at various dates throughout the period. The locked-in discount rate should aim to represent the characteristics of the underlying liabilities in the entire group of contracts. Given that the locked-in discount rate is designed to measure initial and subsequent measurements of the CSM liability, a theoretical market-consistent interpretation would be to set it equal to the weighted average, by a function of contribution to CSM, of the current discount rates throughout the period. This is assuming that various current discount rates have been used to calculate the contribution to Group CSM of the new contracts issued, e.g. on a monthly basis. However, such theoretical approaches may prove challenging to implement in practice due to circular calculations and the multiple model runs required.

In practice, there are various options for determining the discount rate at initial recognition which give similar results to the potential theoretical solution outlined above. Some examples include:

-

Weighted average of current discount rates throughout the period, with different choices of weights; e.g. premiums, BEL, etc.

-

Simple (unweighted) average of current discount rates throughout the period.

-

Start of period discount rate.

Each option has its own operational and commercial implications and the accuracy may depend on the volume of new contracts issued and the volatility of discount rates over the period. For example, the start of period discount rate may be suitable if interest rates have been stable over the year and has the advantage of being market traceable. However, weighted average rates may be more suitable for periods with volatile interest rates and new business volumes, but maybe operationally difficult to calculate and track.

The key financial impacts arise due to the magnitude of CSM profit released due to:

-

1. Interest accreted on the CSM.

-

2. Adjustments to the CSM for changes in estimates of future liabilities, measured at the locked-in discount rate.

However, where these impacts result in a change in CSM and the profit released in insurance revenue, the impact will be offset by a change in profit recognised in the insurance finance income or expenses line.

In conclusion, there are different suitable choices for the locked-in discount rate, where suitability should be assessed based on the financial and operational impact compared to other solutions. The choice of the locked-in discount rate could potentially impact the magnitude of future CSM profit released, however, this will be offset against within insurance finance income or expenses.

4.4.3. Further reading

It will come as no surprise that the issue of locked-in discount rates in the context of stochastic discount rates is complicated both technically and operationally. Readers may find this paper particularly useful to understand the challenges that can arise:

-

IFoA IFRS 17 Future of Discount Rates Working Party: Locked-in stochastic discount rates under IFRS 17

https://www.actuaries.org.uk/documents/ifrs17-wp-locked-stochastic-discount-rates.

Elsewhere, not all practitioners agree that IFRS 17’s requirement to use locked-in discount rates when measuring the GMM CSM is appropriate. Readers may find the following paper useful to see arguments for the use of “unlocked” discount rates for the GMM CSM (noting of course that this is no longer a topic for discussion for the IASB):

-

Institute of Chartered Accountants of England and Wales (ICAEW): Locked-in CSM Discount Rates

4.5. Subsequent Measurement

4.5.1. Overview

The Standard sets out the adjustments that need to be made to the CSM at subsequent measurements. Whilst most items are common, there are some important differences in the adjustments that can be made to the CSM under the GMM and VFA. Tables 10 and 11 summarise the requirements.

Table 10. Adjustments Required to the CSM at Subsequent Measurement – GMM

Table 11. Adjustments Required to the CSM at Subsequent Measurement – VFA

Note that, for underlying contracts issued, the adjustments here are only taken through in so far as the CSM can absorb them. That is, if a given adjustment has the effect of turning the CSM negative, then the excess (below zero) will be recognised in the profit and loss (P&L) account and a LC shall have to be established. This specific requirement (of flooring the CSM to zero) does not apply to reinsurance contracts held.

Section 4.5.2 discusses what these adjustments mean in more detail, section 4.5.3 considers a specific issue that arises in the measurement of participating contracts measured through the GMM and section 4.5.4 discusses the issue of the order in which these adjustments should be made.

4.5.2. Adjustments for experience adjustments

Introduction

Almost always, the actual experience emerging for (re)insurance contracts will be different from the assumptions used at the end of the preceding valuation period. In many cases, the CSM needs to be adjusted for such experience variances.