Australia and New Zealand have some of the highest rates of community treatment orders (CTOs) worldwide, despite the mixed evidence for the efficacy of these orders.Reference Light1,Reference O'Brien2 In an earlier meta-analysis of the predictors and outcomes of CTOs in both countries,Reference Kisely, Yu, Maehashi and Siskind3 people who were male, single and not engaged in work, study or home duties were significantly more likely to be subject to a CTO. In addition, those from a migrant or culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) background were nearly 40% more likely to be on an order. However, Indigenous status was not associated with CTO use in Australia, although there were no New Zealand data. CTOs did not reduce readmission rates or bed-days at 12-month follow-up. However, this is a rapidly expanding area, and in the 2.5 years since our last search we are aware of a number of new studies of the predictors and outcomes of CTOs in Australia and New Zealand.

Although rates of CTO use in Australia and New Zealand are generally high by world standards, there are also considerable variations within both countries.Reference Light1,Reference O'Brien2 For instance, Australian rates range from 41 per 100 000 population in Western Australia to 108.4 per 100 000 in Victoria and 112.5 per 100 000 in South Australia.Reference Light1 Similarly, the national average in New Zealand of 84 per 100 000 encompasses a low of 33 per 100 000 in Canterbury and a high of 151 per 100 000 in the Waitemata.Reference O'Brien2 This is despite the criteria of involuntary treatment being broadly similar across all Australian and New Zealand jurisdictions.4 Unfortunately, our previous systematic review had insufficient studies for a meta-regression to investigate whether differences in CTO use by jurisdiction affected either the predictors or outcomes of CTOs.Reference Kisely, Yu, Maehashi and Siskind3

We therefore undertook a further systematic review and meta-analysis on both the predictors and outcomes of CTO placement in Australia and New Zealand compared with non-CTO subjects. We also investigated whether differences in CTO rates of use by jurisdiction had an influence on either the predictors or outcomes of CTOs through a meta-regression. For instance, higher rates of CTO use might be justified if they resulted in better outcomes. We restricted the scope to these two countries, as opposed to other jurisdictions with clinician-initiated orders such as Canada or the UK. This is because mental health acts (MHAs) across Australia and New Zealand are very similar and, unlike in these other jurisdictions, they are not influenced by entrenched human rights instruments that potentially constrain MHA powers.Reference Brophy, Edan, Kisely, Lawn, Light and Maylea5–Reference Gray, McSherry, O'Reilly and Weller7 The central features of CTOs in Australia and New Zealand are the duty on patients to accept psychiatric treatment and clinician appointments, as well as directions on their type of accommodation in some cases.Reference Dawson6 The legislation also gives powers to provide treatment without consent and to enter someone's accommodation or recall them to hospital (with or without police assistance).Reference Dawson6 Unlike elsewhere, prior involuntary admission to a psychiatric unit is not required.Reference Gray, McSherry, O'Reilly and Weller7,Reference Weich, Duncan, Twigg, McBride, Parsons and Moon8

Method

Search strategy

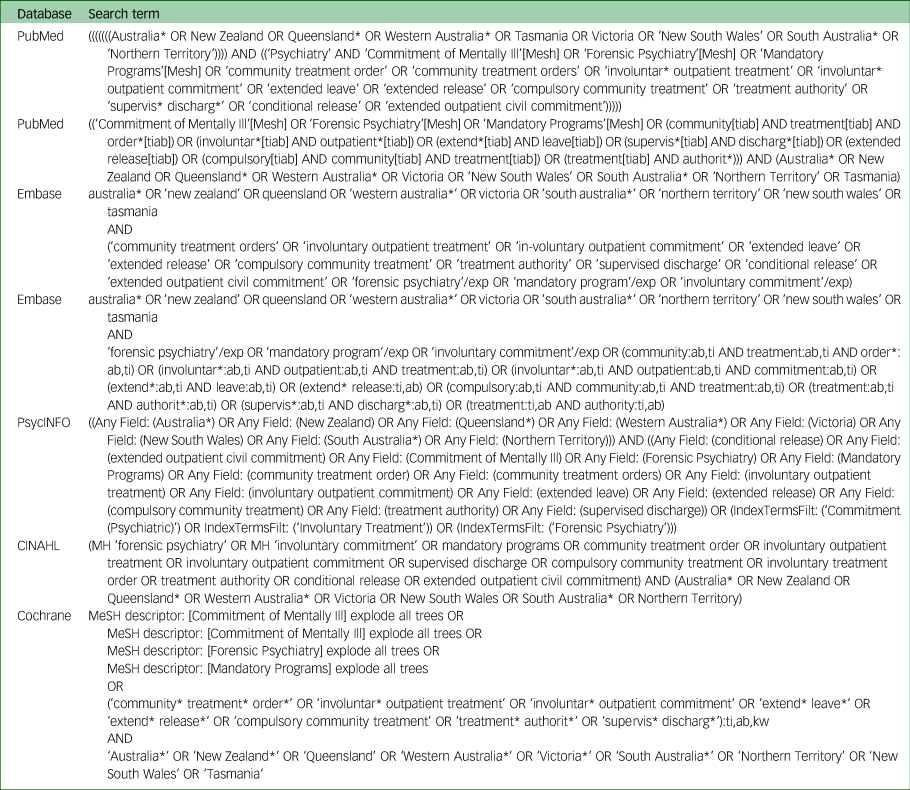

We registered the protocol for this systematic review with PROSPERO (CRD42022351500) and followed guidelines from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman9 The following databases were searched from January 2020 (the date of the last search) to the latest available using identical terms to those used in our previous systematic review: PubMed/Medline, Embase, CINAHL, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and PsycINFO.Reference Kisely, Yu, Maehashi and Siskind3 There were no language restrictions. Table 1 shows the search terms. Ethical approval was not required as all data had previously been published, with one exception. This was for the use of unpublished data from an extension of an included study (see below), for which clearance was given by the Metro South Health Human Research Ethics Committee (LNR/2021/QMS/74836). Individual patient consent was not required as this was an analysis of anonymised administrative data.

Table 1 Search terms

As in our earlier review, two authors independently screened records and abstracts. Where there was a lack of consensus, the third reviewer was consulted. Consensus was achieved in all cases. The reference lists of selected retrieved papers were screened to identify additional studies that met inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

We included any of the following study designs conducted in Australia or New Zealand that compared people on CTOs for severe mental illness with controls receiving voluntary psychiatric treatment: randomised controlled trials, cohort, case–control and cross-sectional studies.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies of compulsory treatment in the community for drug or alcohol dependence, and those that did not include controls from the same jurisdiction receiving voluntary psychiatric treatment.

Possible predictors and outcomes of CTO placement

We investigated whether the following sociodemographic variables were associated with CTO use: age, sex, marital or employment status, and being from an Indigenous or CALD background. We also assessed any associations with clinical features, comorbid substance use, health service or depot medication use, and criminal justice contacts.

Our primary outcomes were hospital admissions, bed-days and community contacts in the 12 months following CTO placement. In the case of admissions, we combined the outcomes of any readmission, the presence of a significant change in admissions and the standardised mean difference (SMD) of the number of admissions. We focused on outcomes at 1 year as this is the most common end-point in the literature and the impact of an intervention on health services beyond 1 year is difficult to ascertain.Reference Kisely, Campbell and O'Reilly10 Where data for this time frame were unavailable, we used those from other follow-up periods. Secondary outcomes included the following over the same time frames: psychiatric symptoms as measured by a standardised psychiatric instrument, concordance with psychiatric treatment, employment, and contacts with the criminal justice system. Data extraction was independently conducted by co-authors working in pairs, with disagreements settled by consensus with or without the assistance of a third reviewer.

Study quality

All studies identified for inclusion were cohort and cross-sectional studies and were independently assessed for quality using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tool for non-randomised studies. This covers the three following areas: selection of the study groups in terms of case definition, representativeness and source of controls; comparability of the groups, such as the use of matching or multivariate techniques; and measurement of exposure and outcomes in a valid and reliable way. The version for cross-sectional studies has eight items and the one for longitudinal designs has eleven. As in other work, a score of seven and above is considered to be an indicator of study quality.Reference Koh, Hegney and Drury11,Reference Chisini, Cademartori, Conde, Costa, Salvi and Tovo-Rodrigues12

Analysis

Where data were available for two or more studies, they were combined in a meta-analysis, giving preference to adjusted data when considering outcomes. We used the following freeware packages: RevMan 5.2, Win-Pepi and OpenMeta[Analyst].13–15 For dichotomous predictors and outcomes of CTO placement, such as gender or readmission, we combined data using the odds ratio (OR). We used the mean difference for continuous data such as the number of bed-days, assessing for publication bias where there were at least ten studies. To maximise statistical power, we combined the SMD of the number of admissions with either the occurrence of readmission or any change in in-patient bed use to create a single dichotomous outcome of ever having been admitted. This is because SMDs can be converted to ORs.Reference Polanin and Snilstveit16 We used an I 2 statistic value of greater than 50% as an indicator of significant heterogeneity. We explored any heterogeneity further through sensitivity analyses of the effects of omitting each study in turn.

We used meta-regression to study whether rates of CTO use had any effects on either the possible predictors or the outcomes of CTOs. We used the number of people per 100 000 on CTOs for the relevant Australian jurisdiction or New Zealand Health Board closest to the time of each study.Reference Light1,Reference Light, Kerridge, Ryan and Robertson17–19

A random effects model was used for all the analyses because we could not definitively exclude between-study variation even in the absence of statistical heterogeneity. Although there is no universally accepted minimum number of studies for a meta-regression, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality in the US recommends that there should be at least six studies.Reference Fu, Gartlehner, Grant, Shamlivan, Sedrakyan and Wilt20

There were several sensitivity analyses. If there was the possibility of an overlap in participants between studies, we either used data from the larger study or studied the effects of using one study or the other. Similarly, although we gave preference to outcomes at 12-month follow-up, we included data from other timeframes but assessed the effects of excluding them from the meta-analyses. Last, we explored the effects on heterogeneity of omitting each study in turn.

Results

We found 1437 citations of interest in the updated search. Of these, 26 full-text papers were potentially relevant and were assessed for eligibility (Fig. 1). Five articles from four studies met inclusion criteria.Reference Ogilvie and Kisely21–Reference Dey, Mellsop, Obertova and Jenkins25 Reasons for exclusion were that articles were conference abstracts or editorials, or that they did not contain primary data, relevant outcomes or suitable controls (Fig. 1). Adding these studies to the previous search meant that there were 35 articles from 16 studies in total (Fig. 1 and Table 2). One of the present review's authors (S.K.) also had unpublished updated data from a previous study on possible CTO predictors, giving a total of 17 studies.Reference Moss, Wyder, Braddock, Arroyo and Kisely26 In another study that used Tobit regression models, the first author kindly provided estimates of effect sizes that were compatible with the other papers.Reference Ogilvie and Kisely21 Of all these articles, 29 could therefore be included in a meta-analysis. Allowing for overlap among the papers, there were approximately 56 541 subjects and 170 156 controls.

Fig. 1 PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 2 Included studies

a. Studies from updated search/data.

b. ICD-10 codes for schizophrenia and related disorders.

Of the 17 included studies that contributed to the 29 articles, five were from Victoria,Reference Segal and Burgess27–Reference Morandi, Golay, Lambert, Schimmelmann, McGorry and Cotton31 four from Queensland,Reference Ogilvie and Kisely21,Reference Parker, Arnautovska, McKeon and Kisely22,Reference Moss, Wyder, Braddock, Arroyo and Kisely26,Reference Kisely, Moss, Boyd and Siskind32 three from New South Wales (NSW)Reference Isobel and Clenaghan33–Reference Harris, Chen, Jones, Hulme, Burgess and Sara35 and two each from Western AustraliaReference Kisely, Preston, Xiao, Lawrence, Louise and Crowe36,Reference Preston, Kisely and Xiao37 and New Zealand.Reference Dey, Mellsop, Obertova and Jenkins24,Reference McKenna, Simpson and Coverdale38 The final study included in this systematic review used data from the second Survey of High Impact Psychosis (SHIP) in seven mental health services across five Australian states.Reference Suetani, Kisely, Parker, Waterreus, Morgan and Siskind23 Research covered more than 30 years from 1990 to 2021.

There was little overlap in participants apart from three instances. In the first, there was a high possibility of overlap between two studies that used Victorian administrative data from the 1990s.Reference Segal and Burgess27,Reference Segal and Burgess39–Reference Segal and Burgess44 We therefore used the study with the larger number of participants. In the second situation, participants from a small Western Australian study were included in larger subsequent work that extended over a decade.Reference Kisely, Preston, Xiao, Lawrence, Louise and Crowe36,Reference Xiao, Preston and Kisely45 However, the smaller study included criminal justice data that were absent from the later study.Reference Xiao, Preston and Kisely45 We therefore used these data to investigate forensic predictors of CTO placement, while using those from the larger study for all the other comparisons. Finally, four Queensland studies included people from overlapping periods.Reference Ogilvie and Kisely21–Reference Suetani, Kisely, Parker, Waterreus, Morgan and Siskind23,Reference Kisely, Moss, Boyd and Siskind32 However, in the case of two studies, samples came from different health services in Queensland.Reference Parker, Arnautovska, McKeon and Kisely22,Reference Suetani, Kisely, Parker, Waterreus, Morgan and Siskind23 A third Queensland-wide study could potentially have included subjects from the other two studies, but it was limited to people under the age of 24 years, whereas the mean ages in the other two studies were in the mid to upper 30s.Reference Ogilvie and Kisely21 Nevertheless, we undertook sensitivity analyses of the effects of excluding the Queensland-wide study. The two studies with samples from individual health services in QueenslandReference Parker, Arnautovska, McKeon and Kisely22,Reference Suetani, Kisely, Parker, Waterreus, Morgan and Siskind23 also overlapped with another Queensland-wide study, but this was limited to one of 15 relevant years.Reference Kisely, Moss, Boyd and Siskind32 Study quality was good, with all but one scoring seven or above on the JBI tool for non-randomised studies (Table 2).

Factors associated with CTO placement

Figure 2 presents forest plots of the factors associated with CTO placement. The diamond at the bottom of each subsection represents the aggregate results and associated 95% confidence intervals from all the studies in the meta-analysis. The result is significant if the points of the diamond do not cross the vertical line. If the diamond is to the right of the line, this indicates that CTO cases are significantly more likely to have that characteristic. For instance, people who were male, single and not engaged in work, study or home duties were significantly more likely to be subject to a CTO (Fig. 2). Heterogeneity was high for all these analyses, with I 2 values greater than 90%. In addition, those from a CALD or migrant background were more likely to be on an order (nine studies, OR = 1.47; 95% CI = 1.37–1.57; P < 0.0001; I 2 = 31%) (Fig. 2). By contrast, Indigenous status was not associated with being on a CTO (seven studies, OR = 1.09; 95% CI = 0.97–1.24; P = 0.15; I 2 = 50%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Factors associated with CTO placement.

Other factors associated with CTO placement were comorbid substance use disorders (five studies, OR = 1.93; 95% CI = 1.55–2.41; P < 0.0001; I 2 = 0%)Reference Ogilvie and Kisely21,Reference Suetani, Kisely, Parker, Waterreus, Morgan and Siskind23,Reference Dey, Mellsop, Obertova and Jenkins25,Reference Bardell-Williams, Eaton, Downey, Bowtell, Thien and Ratheesh29,Reference Morandi, Golay, Lambert, Schimmelmann, McGorry and Cotton31 and prior contacts with the criminal justice system in terms of imprisonment or serious offences (six studies, OR = 1.91; 95% CI = 1.43–2.55; P < 0.0001; I 2 = 52%).Reference Ogilvie and Kisely21,Reference Suetani, Kisely, Parker, Waterreus, Morgan and Siskind23,Reference Dey, Mellsop, Obertova and Jenkins25,Reference Segal, Hayes and Rimes28,Reference Morandi, Golay, Lambert, Schimmelmann, McGorry and Cotton31,Reference Xiao, Preston and Kisely45 In terms of diagnosis, patients with schizophrenia or non-affective psychosis were significantly more likely to be on a CTO (nine studies, OR = 2.41; 95% CI = 1.54–3.78; P = 0.0001; I 2 = 99%).Reference Ogilvie and Kisely21–Reference Suetani, Kisely, Parker, Waterreus, Morgan and Siskind23,Reference Dey, Mellsop, Obertova and Jenkins25,Reference Segal and Burgess27–Reference Bardell-Williams, Eaton, Downey, Bowtell, Thien and Ratheesh29,Reference Kisely, Moss, Boyd and Siskind32,Reference Kisely, Xiao and Jian46 CTO cases were also more likely to have limited insight into the nature of their illness (three studies, OR = 3.26; 95% CI = 2.32–4.58; P < 0.0001; I 2 = 44%).Reference Suetani, Kisely, Parker, Waterreus, Morgan and Siskind23,Reference Morandi, Golay, Lambert, Schimmelmann, McGorry and Cotton31,Reference McKenna, Simpson and Coverdale38

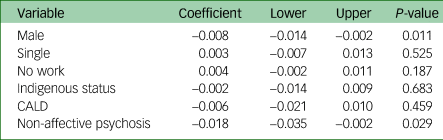

Table 3 shows the results of comparisons where there were sufficient studies for a meta-regression (k ≥ 6). We were unable to include the SHIP study as the data came from five different Australian states with markedly different rates of CTO use.Reference Suetani, Kisely, Parker, Waterreus, Morgan and Siskind23 Higher rates of CTO use were associated with significantly lower proportions of males (Fig. 3(a) and Table 3) and diagnoses of non-affective psychoses (Fig. 3(b) and Table 3). Results for the other comparisons were non-significant (Table 3).

Table 3 Meta-regressions of predictors of CTO placement

Fig. 3 Meta-regression of males (a) and diagnoses of non-affective psychoses (b).

It was not possible to combine in a meta-analysis several other possible predictors of CTO use that were frequently mentioned. These included greater use of health services use prior to placementReference Segal and Burgess27,Reference Segal, Hayes and Rimes28,Reference Burgess, Bindman, Leese, Henderson and Szmukler30–Reference Kisely, Moss, Boyd and Siskind32,Reference Harris, Chen, Jones, Hulme, Burgess and Sara35,Reference Kisely, Xiao and Jian46 and the prescription of depot psychotropics.Reference Suetani, Kisely, Parker, Waterreus, Morgan and Siskind23,Reference Dey, Mellsop, Obertova and Jenkins25,Reference Isobel and Clenaghan33 There was no clear pattern for age. For instance, in some studies younger age was associated with CTO placement, especially in unadjusted analyses,Reference Suetani, Kisely, Parker, Waterreus, Morgan and Siskind23,Reference Segal and Burgess27,Reference Segal, Hayes and Rimes28,Reference Burgess, Bindman, Leese, Henderson and Szmukler30,Reference Kisely, Xiao and Jian46 whereas in another the association was for people who were between 30 and 50 years old.Reference Isobel and Clenaghan33 In two studies there were no significant differences.Reference Parker, Arnautovska, McKeon and Kisely22,Reference Dey, Mellsop, Obertova and Jenkins25 In three studies it was impossible to tell as the controls were matched on age,Reference Kisely, Moss, Boyd and Siskind32,Reference Vaughan, McConaghy, Wolf, Myhr and Black34,Reference Harris, Chen, Jones, Hulme, Burgess and Sara35 and in another three the participants were limited to specific age groups.Reference Ogilvie and Kisely21,Reference Bardell-Williams, Eaton, Downey, Bowtell, Thien and Ratheesh29,Reference Morandi, Golay, Lambert, Schimmelmann, McGorry and Cotton31 One study specifically considered the willingness to have treatment, as opposed to insight in general, and found that this was reduced in CTO cases.Reference McKenna, Simpson and Coverdale38

Effect of CTOs on in-patient outcomes

It was possible to combine results from nine studies. Six presented data for outcomes at 12-month follow-up, and one at 24-month follow-up. In the remaining two studies, the authors did not specify when the outcome occurred with respect to CTO placement. All nine studies considered the influence of potential confounders through the use of matching or multivariate analyses. Depending on the study, these included sociodemographic factors, clinical features, health service use and criminal justice contacts. However, in the case of one study, matching was not entirely successful, with evidence that the CTO cases had more severe illness.Reference Vaughan, McConaghy, Wolf, Myhr and Black34 None of the studies in the meta-analysis adjusted for insight or willingness to have treatment. As before, when the diamond is to the right of the line, CTO cases are significantly more likely to have that characteristic. There were no significant differences between CTO cases and controls in the mean number of bed-days (Fig. 4(a)), but the risk of admission was significantly higher in people on an order (Fig. 4(b)).

Fig. 4 Meta-analyses of bed-days (a), admissions (b) and community contacts (c) over 12 months.

Two studies reported on the mean number of bed-days per admission.Reference Segal and Burgess27,Reference Segal, Hayes and Rimes28 In both cases, this was less for the CTO group than for the controls over the decade of the study (two studies; mean difference = −5.79; 95% CI = −9.18 to −2.40; P = 0.0008; I 2 = 42%). Again, this was without specific reference to the timing of CTO placement. As reported in our earlier meta-analysis,Reference Kisely, Yu, Maehashi and Siskind3 two studies also evaluated the longer-term effects of CTOs, one from Victoria and one from NSW.Reference Burgess, Bindman, Leese, Henderson and Szmukler30,Reference Harris, Chen, Jones, Hulme, Burgess and Sara35 In the former, although the risk of admission increased following an initial CTO placement, there was a lower readmission risk from the fifth CTO onwards. The risk also declined over the 8 years of the study period.Reference Burgess, Bindman, Leese, Henderson and Szmukler30 Similarly, the NSW study found that the greatest reduction in admissions and bed-days compared with controls was in those who had been on CTOs for more than 24 months.Reference Harris, Chen, Jones, Hulme, Burgess and Sara35 This study also reported that CTOs delayed readmission compared with controls over the same period.Reference Harris, Chen, Jones, Hulme, Burgess and Sara35

In the meta-regression, CTO cases in jurisdictions with higher rates of CTO use had significantly worse outcomes than voluntary controls in terms of both a greater number of mean bed-days (coefficient = 0.35; 95% CI = 0.64–0.14; P = 0.014) (Fig. 5(a)) and the likelihood of readmission (coefficient = 0.021; 95% CI = 0.012–0.030; P < 0.001) (Fig. 5(b)) compared to the differences between cases and controls in jurisdictions with lower CTO use.

Fig. 5 Meta-regression of bed-days (a) and admissions (b) over 12 months.

Effect of CTOs on out-patient and/or community outcomes

At 1-year follow-up, CTOs significantly increased the overall number of community contacts (Fig. 4(c)) but not the contacts per month (two studies; mean difference = 1.21 days; 95% CI = −0.14 to 2.57; P = 0.08; I 2 = 84%). In a further study that presented the data as a categorical variable, CTO cases had significantly more community contacts at 2-year follow-up.Reference Dey, Mellsop, Obertova and Jenkins24 There were insufficient studies for a meta-regression for any of these outcomes.

Secondary outcomes

Two papers reported that there were no significant differences in mean scores from the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales between CTO cases and controls at 12-month follow-up.Reference Parker, Arnautovska, McKeon and Kisely22,Reference Kisely, Xiao, Crowe, Paydar and Jian47 However, in the case of one paper, this was not adjusted for baseline characteristics.Reference Parker, Arnautovska, McKeon and Kisely22 The latter paper also reported no significant differences between the two groups in unadjusted scores from the Life Skills Profile-16.Reference Parker, Arnautovska, McKeon and Kisely22 Similarly, a further study reported that CTOs were not associated with fewer subsequent court appearances compared with controls in analyses that controlled for a wide range of sociodemographic, clinical and criminal justice variables.Reference Ogilvie and Kisely21

Sensitivity analyses, heterogeneity and publication bias

Sensitivity analyses of the effects of omitting the Queensland paperReference Ogilvie and Kisely21 where there might have been an overlap in subjects with two other studies did not alter the results,Reference Parker, Arnautovska, McKeon and Kisely22,Reference Suetani, Kisely, Parker, Waterreus, Morgan and Siskind23 and neither did omitting the one study with unpublished data. Similarly, changing the level of adjustment for findings in one study or excluding the two that reported on outcomes other than at 12-month follow-up had little effect. The one exception was the meta-regression of bed-days, which was no longer statistically significant on either sensitivity analysis. Finally, omitting each study in turn in every analysis did not alter significant heterogeneity when it was present.

We were only able to analyse for the effects of publication bias in the comparison of CTO placement by sex, as none of the other analyses had ten or more studies (Fig. 6). The lack of funnel plot asymmetry suggested the absence of publication bias (Fig. 6), and this was confirmed by the non-significant results of both Egger's regression asymmetry (0.35; 90% CI = −2.28 to 2.98; P = 0.857) and adjusted rank correlation tests (Kendall's tau = 0.02; P = 0.929).

Fig. 6 Funnel plot of studies assessing sex as a predictor of CTO placement. OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

This is an update of the first systematic review and meta-analysis of possible predictors and outcomes of compulsory community treatment in Australia and New Zealand.Reference Kisely, Yu, Maehashi and Siskind3 All but one study was of good quality according to the JBI tool for non-randomised studies. The large number of studies enabled the use of meta-regression to explore the effects of rates of CTO placement on both the possible predictors and the outcomes of these orders. The findings may have relevance for other jurisdictions such as Scotland or England and Wales that have similar clinician-initiated orders.

We found that Australians from CALD backgrounds were significantly more likely to be subject to an order, mirroring two studies from the UK.Reference Patel, Matonhodze, Baig, Gilleen, Boydell and Holloway48,Reference Bansal, Bhopal, Netto, Lyons, Steiner and Sashidharan49 Possible explanations include variations in underlying psychiatric morbidity, poor staff attitudes and communication, unfamiliar forms of care and the absence of families, as well as overall system inflexibility.Reference Johnstone and Kanitsaki50,Reference Johnstone and Kanitsaki51 The need for an interpreter may create further barriers to communication and increase the time required to undertake an assessment. Wider societal factors include perceived discrimination, social isolation, unemployment and lower socioeconomic status.Reference Bhui, Stansfeld, Hull, Priebe, Mole and Feder52

In terms of outcomes, CTOs did not reduce bed-days or admissions in the 12 months following placement, in keeping with most non-randomised studies from other countries.Reference Barnett, Matthews, Lloyd-Evans, Mackay, Pilling and Johnson53 However, CTOs may show greater benefit over the longer term, although we were unable to include the data in a meta-analysis. For instance, the study from NSW reported that CTOs had no effect on subsequent bed-days unless patients had been on them for more than 2 years.Reference Harris, Chen, Jones, Hulme, Burgess and Sara35 Two Victorian studies found that CTO cases had fewer bed-days per admission over a decade.Reference Segal and Burgess27,Reference Segal, Hayes and Rimes28 However, in the case of one of these studies, the reduction in the days per admission was associated with an overall mean increase of 15 bed-days.Reference Segal and Burgess27 It is therefore possible that this could represent greater ‘revolving door’ care, whereby individuals have more admissions of shorter duration but spend greater overall time in hospital.Reference Kisely and Campbell54 There is therefore little evidence that CTOs address the issue of the ‘revolving door’, at least in the short term, even though this was one of the main justifications for supervised community treatment in England and Wales.Reference Kisely and Campbell54

Despite the limited evidence, the use of CTOs is likely to continue in Australia and New Zealand and elsewhere. This being the case, it is important to investigate whether there are any situations where CTOs may be useful. The meta-regression results suggested that lower rates of use may lead to more targeted and improved subsequent outcomes. For instance, in jurisdictions where use was lower, people who were male or who presented with non-affective psychoses were more likely to be on CTOs, the characteristic or target profile of those on orders.Reference Churchill, Owen, Singh and Hotopf55 By contrast, there were higher proportions of females and people with diagnoses other than non-affective psychoses in jurisdictions with higher CTO rates. These were also the jurisdictions less likely to show reductions in readmission rates or bed-days at follow-up. Although the study could not be included in the present systematic review because of a lack of controls, these results are consistent with before-and-after work from New Zealand where reductions in health service use following CTOs were limited to people with schizophrenia.Reference Beaglehole, Newton-Howes and Frampton56,Reference Beaglehole, Newton-Howes, Porter and Frampton57

The mode of discharge from an order may also affect outcome.Reference Vine, Turner, Pirkis, Judd and Spittal58 In an analysis of Victoria-wide administrative health data, people whose CTOs were discontinued by their treating service were less likely to be placed on a subsequent order than those who were discharged by the Mental Health Review board or those where the order was allowed to expire. Although this was an observational study, the authors adjusted for obvious confounders such as sociodemographic characteristics, CTO duration and diagnosis.Reference Kisely59 The authors suggested that unplanned or abrupt discharge arising from expiry or discharge by the review board may therefore be associated with worse outcomes, indicating the need for better engagement by treatment services with people who experience severe mental illness.Reference Vine, Turner, Pirkis, Judd and Spittal58

A decade ago, Light and colleagues highlighted the ‘invisibility’ of CTOs and the lack of clarity as to where they fit into mental health policy frameworks, as well as what contribution CTOs make, or should make, to the care of people with mental illness.Reference Light, Kerridge, Ryan and Robertson60 This remains the case despite subsequent reforms of mental health legislation Australia-wide and raises questions about both the transparency and the accountability of the mental health system, and whether this silence leads to greater marginalisation and discrimination towards people with mental illness. At the very least, there should be further enquiry into how CTOs may be better used to improve outcomes. This could include more focused use, greater consideration of the appropriate diagnosis and better engagement by treatment services for those on an order.

There are several limitations to this systematic review. All the included studies were observational, and many used administrative health data. These may be subject to recording bias and lack information on social disability. We were also only able to investigate the effects of broad diagnostic categories such as non-affective psychoses because of variations in how diagnoses were described. Cases and controls may have differed in ways for which it was not possible to match or adjust, such as insight, and studies used proxy indicators of CALD status including place of birth and preferred language. We have also only demonstrated significant associations, not causality. For instance, the current study could not determine whether differences in outcomes between high- and low-use jurisdictions were due to variations in the severity of symptoms or a lower threshold for the use of compulsion in general.

The results of our meta-analyses showed a high degree of heterogeneity. We explored this further by excluding each study in turn, but this made little difference. Although we accommodated heterogeneity by using a random effects model, our findings should be viewed with caution. In addition, we were only able to conduct meta-regression for a limited number of possible predictors and outcomes. The results of the meta-regression for bed-days were no longer statistically significant on sensitivity analyses. However, the results of the other meta-regressions were unaffected, including those for readmission. We were also only able to investigate the effects of differences in rates of use by jurisdiction and could not consider differences in other factors that may influence CTO placement or outcomes. These factors might include the following: the effects of human rights instruments; recovery-oriented policies; environmental factors, including demographics; the availability of in-patient beds and clinical community-based resources; and peer or service culture.Reference Light1 We restricted the current review to Australia and New Zealand to reduce possible differences. However, the influence of these variables requires further study. Finally, we were only able to test for publication bias in one comparison, as none of the others had ten or more studies.

In conclusion, there are marked differences in the possible predictors and outcomes of CTO placement between high- and low-use jurisdictions. These findings cast further doubts on how CTOs are used, as well as their ultimate effectiveness, and warrant further investigation to establish whether better targeted placement might improve outcomes. This is of concern in both Australia and New Zealand, as well as in other jurisdictions such as England, Scotland and Canada that have similar although less extensive clinician-initiated orders.

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contributions

S.K. had the original idea for the paper. Study selection and data extraction were carried out by the three authors working in pairs (S.K., L.M. and D.S.) with any disagreements resolved by consensus or the third author. S.K. wrote the first draft, which was then revised critically for important intellectual content by all other authors.

Funding

D.S. was funded in part by an NHMRC Emerging Leadership Fellowship: GNT1194635.

Declaration of interest

S.K. and D.S. are members of the international editorial board of the BJPsych, and S.K. is also on the editorial board of BJPsych International.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.