The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health, ICF (World Health Organization, Reference World Health Organization2001) is gaining more and more ground in terms of interest, recognition, and use in Germany, especially in the fields of social medicine, medical and vocational rehabilitation (Rentsch & Bucher, Reference Rentsch and Bucher2005; Ewert, Freudenstein, & Stucki, Reference Ewert, Freudenstein and Stucki2008). When the ICF was endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2001, there was great support for the idea of expanding the model for classifying impairment, disability, and handicap. Since that time, classification efforts have expanded beyond the sequelae of diseases. Additionally, they have also addressed the potential influence of external environmental factors, as well as the internal contexts that are integral to the individual.

Contextual factors are extremely important in working with the ICF (Fries & Fischer, Reference Fries and Fischer2008). Personal factors play an essential part in effecting health problems and the impact of disability on inclusion. WHO describes personal factors as internal factors, which ‘may include gender, age, coping styles, social background, education, profession, past and current experience, overall behaviour pattern, character and other factors that influence how disability is experienced by the individual’ (WHO, Reference World Health Organization2001, p. 11). We define personal factors as the particular background of an individual's life and living, including features of the individual that are not part of a health condition or health states, and which can impact functioning positively or negatively. Nevertheless, personal factors are not yet classified in the ICF; ‘Their assessment is left to the user, if needed’ (WHO, Reference World Health Organization2001, p. 19). As a result, some users of the ICF have generated lists of ‘personal factors’ for their own use.

Personal contextual factors play an essential part in the model of the ICF. Classifying these factors is most useful when the criteria reflect the country-specific social and cultural environment and its particular linguistic terms. To date, only a few proposals for a user-oriented list of personal factors have been published worldwide (Geyh et al., Reference Geyh, Peter, Müller, Bickenbach, Kostanjsek, Üstün and Cieza2011).

To begin with, some doubts arose as to whether personal factors are too personal to be classified. The workgroup discussed whether health care ethics (see Peterson, Reference Peterson2010), and data privacy protection constitutes an obstacle in shaping this discussion. Personal factors should not be used to stigmatise, label, or otherwise blame a person. Instead, the objective is to respect the individual's needs and strengths (United Nations, Reference United Nations2006).

To neglect the topic of personal factors would mean accepting the ICF as an incomplete instrument. In fact, personal factors have an impact regardless of whether they are categorised. Compiling a catalogue helps health care professionals, as well as people with or without a health problem, gain a comprehensive perspective about a person's condition, be it in the context of rehabilitation or for other reasons.

Classifying personal factors sensitises people to their role in health-related issues. Failing to address personal factors would mean ‘losing sight of the person and of the full background of each person's life and living, which is the context of functioning and disability’ (Geyh et al., Reference Geyh, Peter, Müller, Bickenbach, Kostanjsek, Üstün and Cieza2011, p. 1099), thereby raising possible ethical concerns. Thus, in the rehabilitation and other fields: ‘. . . personal factors can play a role in all stages of the rehabilitation process. . ., in assessment, goal-setting or matching interventions to the person's characteristics’ (Geyh et al., p. 1098).

Previous Research

Efforts to identify and document personal factors have thus varied in scope and purpose. For example, Stephens, Gianopoulos, and Kerr (Reference Stephens, Gianopoulos and Kerr2001) proposed personal factors with hearing impairment in the context of the ICF. They identified the following to be important attributes: ‘Other health conditions, coping styles, past and current experience, overall behaviour pattern and character style, and individual psychological assets’ (p. 298). Ueda and Okawa (Reference Ueda and Okawa2003) considered personal factors to have a ‘subjective dimension’. In their 2004 study, the Heerkens, Engels, Kniper, van der Gulden, and Oostendorp (Reference Heerkens, Engels, Kniper, van der Gulden and Oostendorp2004) workgroup addressed the topic of work-related disability and made a distinction between general personal factors such as age, sex, education, lifestyle and mental factors (including coping) versus work-related personal factors such as motivation, experience and willingness to exertion [sic]. Badley (Reference Badley2006) proposed a three-tiered categorisation: scene-setting personal factors, potentially modifiable personal factors, and social relationships. In Australia, Howe (Reference Howe2008) examined this issue from the perspective of treating speech-language pathology and proposed personal factors that were relevant in this context. He suggested differentiating between potentially changeable factors and those which are more difficult to change, or unchangeable. Huber, Sillick, and Skarakis-Doyle (Reference Huber, Sillick and Skarakis-Doyle2010) distinguished between personal factors such as coping styles, social background, past and current experiences and individual psychological assets on the one hand, and an individual's personal perception of his or her own health condition on the other hand, explaining: ‘Attributed meaning results from individuals’ aspirations and intentions, the foundations for their self-perceptions’ (p. 1964).

Quite clearly, a gap exists between the importance of personal factors and shortcomings in how they are classified, a challenge for ICF users. Taking a first step toward resolving that gap was the goal of this study.

Preliminary work by the German Medical Advisory Board of Statutory Health Insurances (Medizinischer Dienst der Krankenversicherung [MDK]) to develop a systematic approach to incorporating personal factors in 2006 (Viol et al., Reference Viol, Grotkamp, van Treeck, Nüchtern, Manegold, Eckardt and Seger2006) suggested that personal factors could be used by social medicine specialists in statutory health insurances in assessing the need for interventions (e.g., rehabilitations measures or paid sick leave), and that these factors needed specification. This study builds on the previous research by Viol et al.

Goal of the Study

The study aimed to compile a preliminary ICF-based list of personal factors for a German-speaking region as a basis for a comprehensive discussion about the possible format of personal factors in the ICF. It is generally assumed that the process of classifying personal factors is most useful when the criteria reflect the country-specific social and cultural environment and its respective linguistic terms. WHO has not yet classified personal factors for global use. Suggesting personal factors for German-speaking countries reflects the principle of having a catalogue of personal factors compiled for a rather circumscribed social and cultural setting. Once it has been defined for this area, however, we believe the proposal may be of interest for other countries, too.

The research questions of this study were: (1) What criteria for the selection of items into a list of personal factors for the German speaking area can be agreed upon? (2) What items are to be included into this list? (3) In what systematic structure can the personal factors agreed upon be arranged?

We aimed at creating a list that is more sophisticated than just a sampling of examples as offered by ICF or by the Australian User's Guide (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2003). Our intention was to be comprehensive with regard to structure, but not too detailed for this preliminary and regional proposal.

Method

Research Design

To develop a catalogue of personal factors, we used an interpretive qualitative approach (Mayring, Reference Mayring1996). First, the approach has the advantage of allowing for holistic reflection on the health problems in interaction with contextual factors. Second, we take the view that qualitative, consensual-driven introspection by a team of experts is a legitimate means of knowledge. Third, the consensus-driven inductive methods we engaged allowed us to generate a stepwise thematic generalisation out of separate content or item observations. Our interpretive qualitative approach yielded valid rules to map the association between a health problem and personal factors, taking into account the relevant context.

Participants and Setting

The ICF working group of the German Society of Social Medicine and Prevention (DGSMP) represented a wide spectrum of institutions, mainly from medical fields, especially physicians in social insurance and rehabilitation institutions, as well as experts from other professional groups (see Appendix A for full list of participants). Table 1 summarises the participant organisation and member characteristics. The work of Viol et al. (Reference Viol, Grotkamp, van Treeck, Nüchtern, Manegold, Eckardt and Seger2006), on which this proposal was based, was created by nine physicians of the Medical Advisory Board of Statutory Health Insurances. The proposal presented is based on a broader community of 18 ICF users and their experiences in various institutions. The stakeholder group was expanded more broadly and included patients' representatives (Table 1).

TABLE 1 The German Society of Social Medicine and Prevention (DGSMP) Participant Profile

Note: The numbers in brackets are the expert personnel from the respective organisation. Multiple affiliations possible.

As described, the list presented was drafted based on an expert consensus by self-selected members of the German Society for Social Medicine and Prevention (DGSMP). There was no election procedure or commission from the WHO or any institution. Instead, experts who work with the ICF in their various professional settings did an exploratory work, as it were, because they were convinced of the benefits of having a comprehensive list of personal factors. Access to the working group was open to all experts who deal with the ICF in their professional setting. The result was a thoroughly comprehensive group of German specialists from different health care insurance companies and institutions.

Data Sources and Collection

The starting point for data collection was the publication by Viol et al. (Reference Viol, Grotkamp, van Treeck, Nüchtern, Manegold, Eckardt and Seger2006). The items listed by this workgroup were thoroughly revised in a consensus procedure. At the beginning, six rules for the working group were established:

1. The list of personal factors should be developed using the study of Viol et al. (Reference Viol, Grotkamp, van Treeck, Nüchtern, Manegold, Eckardt and Seger2006) as a starting point.

2. The items exemplarily mentioned by WHO were to be incorporated.

3. The approach was decided to be all embracing and universal.

4. The categories agreed upon were to be neutral, manageable, relevant, and clear, without ambiguity.

5. Overlapping with terms already part of another component of ICF was to be avoided; if not avoidable, the character of an item selected as personal factor should clearly be justified as such.

6. The neutral stand of ICF with regard to aetiology is a convention for personal factors too. The pool of items was reviewed, applying the criteria for agreed-upon selection and taking into account the various perspectives of the participants.

Criteria for Selection

The workgroup agreed that a list of ICF personal factors needed to be as comprehensive, universal, neutral, user-friendly, relevant, unequivocal, definitive in their focus, and nondiscriminatory as possible.Footnote 1 These criteria served as a standard for whether or not a factor was to be included. From a technical perspective, overlaps with other components of the ICF (homonymic items in two components) were avoided. If this was not possible, the use of such corresponding pairs had to be justified.

Data Credibility and Trustworthiness Checks

We made use of expert interviews in the form of a chaired discussion (Gläser & Laudel, Reference Gläser and Laudel2006) and literature control (Geyh et al., Reference Geyh, Peter, Müller, Bickenbach, Kostanjsek, Üstün and Cieza2011) to determine the credibility and trustworthiness of the data from the qualitative procedures we engaged. Using these procedures, we achieved a level of procedural oversight in consensually mapping the categories (through deductive theoretical selection criteria) for personal factors that could act as a barrier or facilitator in association with a health problem. Systematic content analysis (Mayring, Reference Mayring1996) helped to reduce and systematise linguistic basic material we accumulated.

To ensure unanimity, we also developed criteria for the selection of items, including a formal decision-making process for collating items and mapping them to the ICF. For compatibility with the ICF structure, the items of the list were marked alpha-numerically, corresponding to the ICF's standard. Once compiled, the list was sent to nine experts who had not participated in developing the proposal for cross-validation of the mapping, for review.

Procedure

The members of the working group had nine meetings during the period from June 2009 to November 2010. We started by discussing the obstacles and difficulties, defining the goals of the group and the group's understanding of personal factors, and constituting the rules for working and the criteria for inclusion or exclusion. Every item proposed for inclusion was intensively evaluated to assess whether it fulfilled the preconditions. The process of data collection and data analysis were connected; that is, selecting categories led to establishing a structure of chapters.

The next step was to reach a consensus on the structure of the chapters and the number of levels in the classification. In subsequent meetings, items were either added or removed, chapters combined, and the completed list was reviewed. External reviews (n = 9) were carried out by Swiss professionals from Zurich Pedagogical University and from the Hospital of the Canton of Lucerne, by the coordinator of the translation of the ICF into German, and by Physicians of Public Health and of patients' associations. Regular progress reports on the status of the proposal were provided within the DGSMP. Suggestions and representations also came from other experts, from inside and outside the DGSMP (e.g., Rohwetter, Reference Rohwetter2011; Cibis Reference Cibis2011). The prototype proposal was published as a work in progress (Grotkamp et al., Reference Grotkamp, Cibis, Behrens, Bucher, Deetjen, Nyffeler and Seger2010). After this, new members joined the working group in 2011 (see Table 1), increasing the discipline areas represented.

Data Analysis

The list of items proposal was reviewed both by external experts from medical fields who were not previously involved in the discussion process, as well as by members of other professional groups. The objective of the review process was to make sure that the proposal was logically consistent within itself, current in terms of its content, comprehensive, and comprehensible in its scope. The answers, questions, and remarks we received, most of them very helpful (e.g., ameliorating the terms chosen, mentioning the importance of ethical considerations, or being afraid of medical predominance), were used to improve the proposal. The workgroup affirmed that the proposal was also aimed at children and youth.

Levels of Personal Factors

In developing the components of personal factors, the workgroup followed the template of the ICF, which distinguishes among four levels: first level = chapter level; second level = prefix + 3-digit code (= short version); third level = prefix + 4-digit code; and fourth level = prefix + 5-digit code (only for body functions and structures).

The ICF has ‘blocks’ (i.e., interim steps) between the first and second level of the components of body functions and activities/participation. However, these blocks cannot be coded in the ICF. In this proposal, blocks were used if the categories needed only a second level (chapters 3, 4, and 5). If a third level was needed, blocks were not used (chapters 1, 2, and 6).

Qualifiers

Analogous to the WHO's recommendations about classifying environmental factors, items in the category of personal factors can be defined as a qualifier — that is, a barrier or a facilitator — in terms of their impact on functioning. The categorisation here depends on the observer or person doing the assessment and on the issue in a given situation. This means that determining whether contextual factors are qualifiers is a more subjective process than determining disabilities. There are only a few items in the first two chapters where further objective depiction is possible, such as stating someone's age in years or body height in centimetres.

In compiling the chapters a question arose as to whether the categories attached to them were sufficient. Every relevant factor was intended to be included. Whether an item was included in the proposal or not depended on whether the criteria agreed upon for selection (see below) were fulfilled. Data analysis brought up some crucial questions, that is, how to draw the line between personal factors and body functions and structures (see discussion). We resolved the problem by focusing on the perspective and definition of the different components of the ICF.Footnote 2

Ethical Considerations

‘With so many potential uses, there are many opportunities for potential misuse’ (Mpofu & Oakland, Reference Mpofu and Oakland2010, p. 56). We sought neutral, not discriminatory terms, and took into account the ethical considerations that are essential to using the ICF at all, emphasising that the ethical guidelines included in annex 6 of the ICF (WHO, 2001) have to be respected when applying personal factors in particular.

Results and Discussion

This study proposed to develop a systematic and well-structured approach to incorporating personal factors into the use of the ICF. Only a few researchers and organisations have addressed this issue. ICF users have to create lists of their own. That is why the proposal is designed to expand and contribute to the process of discussing (and potentially standardising) the classification of personal factors in the ICF on an international level. Previous research makes a distinction between stable and modifiable (Badley, Reference Badley2006; Howe, Reference Howe2008), objective and subjective (Ueda & Okawa, Reference Ueda and Okawa2003), demographic and nondemographic (Badley, Reference Badley2006), and general and work-related factors (Heerkens et al., Reference Heerkens, Engels, Kniper, van der Gulden and Oostendorp2004). Our findings partially correspond with the conclusions of other authors; for example, the overlapping of proposed factors in chapters 2 and 3 with body functions (see Badley). The differentiated structure here was selected not only in order to correspond to the component of the environmental factors. Our system of the six chapters described earlier seemed expedient and logical.

Proposal for a List of Personal Factors

Tables A1 to A6 in Appendix A show the suggested list of personal factors. The draft categorises the 72 categories into 6 chapters.

Chapter 1 (see Table A1) contains general personal characteristics such as age, sex and genetic factors. Gender and age are items mentioned by WHO as examples and are generally accepted. The voting procedure led to exclusion of formerly included categories such as ethnicity or race (see Viol et al., Reference Viol, Grotkamp, van Treeck, Nüchtern, Manegold, Eckardt and Seger2006) in favour of the more comprehensive category of genetic factors, and to the renouncement of a specific chapter ‘Ageing’.

Chapter 2 (see Table A2) lists physical factors as body measurements or handedness, while chapter 3 (Table A3) lists mental factors (personality factors and cognitive factors). Both chapters are concerned with existing but modifiable factors, and the person's physical and mental constitution. Some items cover categories of body functions and body structures; however, the focus was on how they impact upon functioning with respect to disability. Badley (Reference Badley2006) also mentions physical characteristics and psychological traits as ‘scene setting personal factors’ (p. 9). Stephens et al. (Reference Stephens, Gianopoulos and Kerr2001) refers to these as ‘individual psychological assets’ (p. 298), and in Heerkens et al.'s (Reference Heerkens, Engels, Kniper, van der Gulden and Oostendorp2004) description, mental factors, together with general characteristics, belong to general personal factors, in contrast to work-related personal factors.

Factors that are more associated with lifestyle (attitudes, basic skills and behaviour patterns) constitute chapter 4 (see Table A4) of the proposal. This chapter covers a broad range of categories that are at least partially modifiable. Attitudes and behaviour patterns have been proposed for classification by other authors, too. Basic skills were considered to be relevant categories influencing functioning and disability.

Life situation and socioeconomic/sociocultural factors are represented in chapter 5 (see Table A5). Sociodemographic factors have also been accepted as personal factors by Badley (Reference Badley2006) and Howe (Reference Howe2008).

Chapter 6 (see Table A6) comprises other health factors. There was an intensive discussion whether this chapter was necessary or whether the items of this chapter should belong to health conditions. The decisive factor for its inclusion was the fact that WHO accounts for ‘other factors’ as personal factors (see above), and the need for a classification of former health problems that are no longer a health problem or in connection with disability, but which may function as facilitator or barrier in the context of another, new health problem.

Three major themes are the focus of our discussion: overlapping components, likely missing factors, and unnecessary factors.

Overlapping Components

In the proposed catalogue of personal factors, there are terms that at first seem similar or identical to items of other components of the ICF. This surprising fact seemed inevitable in the process of developing this instrument. Using the ICF, Body Functions and Body Structures can be considered as positive or negative aspects. Nevertheless, using qualifiers, we can only classify the degree of the impairment (i.e., only negative, not positive deviations). The ICF does not offer a way to classify the fact that a body function or structure influences health positively because of a favourable body function or structure (e.g., an exceptionally athletic build). However, personal attributes may influence a person's functioning or disability (e.g., during rehabilitation measures). As a result, those items were listed as personal factors as they were not regarded from the perspective of disability, but as contextual factors influencing functioning in a positive way. Our intention was to create a classification that would identify all sorts of factors that influence a person's functioning or disability. Otherwise, facilitators pertaining to body function or structures that positively influence functioning could not be described.

We propose that if a body function, body structure or activity may have a positive effect on the person's functioning or disability that cannot be classified otherwise, this item should be allocated to the personal factors. For example, dietary restrictions due to dysphagia should be designated as an activity limitation. On the other hand, particular eating habits that can have a positive or negative effect on current functioning are considered a personal factor. A prior infection with rubella may be considered a positive effect if a pregnant woman is exposed to rubella, and therefore it would be categorised as a personal factor, not impairment.

Similarly, allocating overlapping categories to either environmental or personal factors depends on the perspective of the observer. Items are allocated to the individual's personal factors if the characteristics in question are integral to that person. An example here would be fearfulness as a consequence of having experienced inadequate pain relief during surgery. If the influences are external forces that affect a person, such as other people's attitudes towards the individual's current health situation, they are classified among the environmental factors.

Are Any Important Factors Missing?

This draft proposal deliberately does not include complex issues such as motivation or compliance. These factors are the result of various influences; for example, attitudes, behaviour patterns, socioeconomic status. ‘Motivation’ or ‘compliance’ do not exist per se. Someone may be motivated for rapid return to work after illness, but not motivated for an intervention. Describing the various relevant personal factors as proposed, however, can help evaluate someone's motivation for such things as returning to work or accepting a risky treatment.

Have Any Unnecessary Factors Been Suggested?

Reviewers pointed out that some factors were not relevant in their context — for instance, genetic factors or other health factors — while others could be more differentiated, such as factors that are meaningful in assessing work incapacity or willingness to perform. The classification's purpose is to be useful for any given constellation of functioning and disability in relation to a health condition. In other words, a balance has to be found between attempting to be comprehensive and creating a manageable volume.

Limitations of the Study

The authors were aware of the limitations of the methodological approach to the construction of the proposed classification. The study may be critically considered as a combination of brainstorming, compilation of lists of personal factors of ICF users in Germany and Switzerland, and constructing a proposed inventory, as described. The qualitative approach was intended as a first step. It might be followed by more sophisticated studies asking for the quantitative impact of each factor (see, e.g., Ziegler & Bühner, Reference Ziegler and Bühner2009).

This proposal was not compiled by corresponding to WHO rules for bringing a classification into the WHO-FIC (see Madden, Sykes & Ustun, Reference Madden, Sykes and Ustun2007). It is rather to be seen as a forerunner, a contribution to ICF users missing an official classification, and as a ‘bottoms up’ contribution to stimulate the international discussion of personal factors. This work represents the views of the participants and the conclusions may represent the personal and professional biases of the study participants. Additionally, the impact of professional disciplines (e.g., medicine) may have influenced the process and the final product. Finally, the limited number of participants may restrict the generalisability of the study.

This proposal has been reviewed by German-speaking experts. Additional review and approval processes are suggested on an international level to make sure the instrument develops further. The suggested classification of personal factors is not to be seen as a checklist to be worked through from top to bottom. After all, physicians do not use the ICD to generate a diagnosis; instead, they use it as a standardised way to document their diagnoses, based on their own findings and assessments. By the same token a classification of personal factors can be applied.

Conclusion

To summarise, personal factors play an essential part in effecting health problems and the impact of disability on inclusion in society. This article presents one of the world's first systematic attempts at cataloguing personal factors in order to stimulate a discussion about the fourth component of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.

The study incorporated the experiences of ICF users in Germany and Switzerland who work with lists of personal factors in their daily work. The working group did not choose an approach that required reviewing literature and numbering what items were mentioned and how often. We used a different approach, but both approaches seemed us to be legitimate. Nor was it our ambition to bring the classification into the WHO-FIC at this preliminary stage. The workgroup sees this draft as a basis for a comprehensive discussion about the possible format of personal factors in the ICF. We hope that this classification proposal stimulates dialogue that may or may not lead to changes at a systemic level globally. Based on the experiences of ICF users in Germany and Switzerland, the working group intended to develop a list of personal factors that should cover every relevant factor, be suitable for all intents and purposes, but nevertheless of limited complexity. Classifying the personal factors of the ICF provides a standardised tool for describing relevant personal factors and their influences on a person's functioning.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the members of the ICF workgroup for their dedication and hard work in creating this draft, especially Prof. Dr. Christoph Gutenbrunner, Hannover Medical School (MHH), Director of the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Hannover, Germany, and Dr. Klaus Keller, Rehabilitation Clinic Herzogsaegmuehle, Rehabilitation section, Peiting-Herzogsaegmuehle, Germany. We are deeply grateful as well to Prof. Dr. Elias Mpofu for his professional and effective editorial support and supervision to prepare our draft for publication. We would also like to thank Laura Russell in Karlsruhe, Germany, for her professional guidance in translating the German into English items.

Conflict of Interests

None declared

Appendix A

Table A1

Chapter 1

General personal characteristics

This chapter addresses the inherent general characteristics such as age, sex and genetic factors that may have an effect on a person's health.

This chapter does not cover characteristics that correlate to impaired health status or a disease.

Table A2

Chapter 2

Physical factors

This chapter addresses the factors of the physique and other bodily criteria to whatever extent they affect the person's ability to function and the body's potential to change. The term refers to a person's congenital or acquired constitution and their existing functional capacities. Health conditions or diseases that impair the current functional status are classified among body structures and functions. Mental factors (Chapter 3) are not covered in this section.

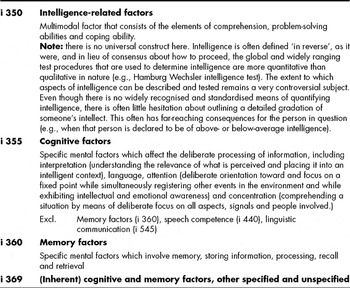

Table A3

Chapter 3

Mental factors

This chapter addresses a person's inherent mental factors. Mental factors may serve as facilitators and barriers that affect functioning. Health conditions or diseases that impair the current functional status are classified among body structures and functions. Mental factors include personality factors as well as cognitive factors (incl. mnestic factors).

Personality factors (i 310–349)

General mental factors that influence a person's constitutional nature in terms of their individual responses to a situation; these include the emotional characteristics which distinguish one person from another. If these personality factors become pathological, they are not classified among personal factors but among the mental aspects of body functions. (Personality factors fall along a continuum between two extremes. As a result, both the extent of the trait and the predominant pole can be mentioned.)

Cognitive and mnestic factors (i 350–369)

Specific mental factors which are inherent and serve as a facilitator or barrier to functioning. If these cognitive and memory factors reach a pathological state, they are not classified among personal factors but grouped with body functions. An emphasis was placed here on the facilitating or impeding nature of the effects because of the fact that there is not thorough scientific consensus about the practical aspects of classifying these topics.

Table A4

Chapter 4

Attitudes, basic skills and behaviour patterns

This chapter deals with a person's attitudes, basic skills and behaviour patterns that can be relevant in coping with the effects of disease and health conditions. Attitudes, basic skills and behaviour patterns are elements that can have a varying influence on a person's lifestyle. They may serve as facilitators (e.g., protective/salutogenic factors) or barriers (e.g., risk factors). A person's attitudes, basic skills and behaviour patterns influence their motivation when it comes to interventions and changes in behaviour. Basic skills can include issues such as the ability to develop coping strategies in dealing with the effects of a health condition, whereas some behaviour patterns can exacerbate existing problems.

The chapter does not include activity limitations as the result of a disease or health problem; these are classified with the component of activities and participation.

Attitudes (I 410–429)

The cumulative sum of personal values, convictions and opinions which are usually inherent in nature and affect an individual's behaviour and life in certain areas.

Basic skills (i 430–449)

General skills (including the fields of social skills, methodical skills, empowerment, action-related skills and media skills) which form the basis for adapting and transferring more specific skills. These basic skills include general life knowledge as well as the abilities and aptitude to apply this information appropriately. Basic skills are also called core skills or life competence. Motivation is a multimodal factor consisting of elements such as attitudes and a willingness to work and take action. This is why the concept of motivation is not classified separately.

Behaviour patterns (i 450–479)

Long-term behaviours that have become routine due to repetition. This category does not include one-time, deliberate or situationally dependent behaviours.

Table A5

Chapter 5

Life situation and socioeconomic/sociocultural factors

This chapter focuses on the factors of someone's immediate personal life situation, regardless of whether they actively influence it or not. In this chapter there are many corresponding items found under environmental factors which describe the effects that a life situation has on a person.

Immediate life situation (i 510–529)

Table A6

Chapter 6

Other health factors

The ICF mentions that personal factors can also involve ‘other health conditions’ that are not part of a person's overall health status but are able to affect their current functioning. These health factors can cumulatively or individually play a part when describing functioning and disability at any level (e.g., pregnancy). Comorbidities must be regarded separately; they are to be classified among health conditions.

Table A7

Participants — Working group ICF of Section II of the German Society for Social Medicine and Prevention, DGSMP, (*new members since 2011)