Legitimate elections, those that are conducted in a free and fair manner and accepted by opponents, incumbents, and the population, are a necessary hallmark of democracy. The mere ability to hold elections is necessary but not sufficient for peaceful transitions of power in democracies. In democratizing states, legitimate elections are a key mechanism through which democratic gains and self-enforcing democratic norms are institutionalized.Footnote 1 Even in competitive autocracies,Footnote 2 elections serve as an accountability mechanism, albeit to a lesser degree. For each of these contexts —consolidated democracies, democratizing states, and competitive autocracies — the degree to which elections are governed in a free and fair manner both varies and has myriad consequences. Broadly speaking, unfree, unfair, and exclusive elections are associated with both electoral violenceFootnote 3 and greater degrees of clientelism and corruption, impeding development.Footnote 4 They have further been identified as pivotal stumbling blocks in processes of both democratic transition and consolidation.Footnote 5 In light of the pivotal role elections play in democratic stability and democratic transitions, and the negative outcomes associated with elections characterized as unfree and/or unfair, electoral management is of central importance. The literature to date suggests that electoral management characterized by higher degrees of autonomy and capacity are associated with the highest quality elections.Footnote 6

Electoral Management Bodies (EMB), tasked with organizing and carrying out all or portions of elections, are varied in both design and governance. Here, design refers to the process of the formation of a body, including the calculations and parties involved in formation and the nature of its implementation,Footnote 7 and governance describes the formal categorization of electoral oversight according to its degree of autonomy. Hartlyn and colleagues describe EMB governance as involving “the interaction of constitutional, legal, and institutional rules and organizational practices that determine the basic rules for election procedures and electoral competition.”Footnote 8 Therefore, both design and governance, the intent and form of an EMB, are critical determinants in both the autonomy and capacity of the resulting body.

In recent years, constitutionalized, independent bodies have become more popular. This is a trend largely associated with third wave democracies. As of 2013, more than 54% of states had some form of electoral oversight stipulated in their constitution.Footnote 9 This represents an approximate 98% increase from the period prior to the third wave, beginning in the mid-1970s. The move toward constitutionalized independent electoral management of late leads to questions concerning the efficacy of such bodies. This article takes up two issues and we ask: What are the trends in EMB governance and design and the degree to which they produce autonomous, capable bodies; and to what degree and under what conditions does such autonomy and capacity lead to better electoral outcomes?

The article proceeds as follows. First, we review the literature concerning EMBs governance methods and institutional design and, separately, more recent research focusing on EMB efficacy. Second, we provide a robust description of the data, pointing to trends related to space, time, and institutional form. Third, we describe the available data and our empirical strategy. Next, we present the results of our analyses and situate them in the extant literature. Finally, conclusions and areas of future research are offered.

Literature Review

Electoral Management Bodies: Form and Function

The peaceful transition of power from one incumbent to the next is largely taken for granted in established democracies. Yet, for states that are newly democratized, undergoing transitions, attempting to escape a conflict trap, or attempting to ward off escalating violence in a polarized atmosphere, the ability to hold legitimate elections is of the utmost importance. Moreover, even in established democracies, such as the United States, peaceful transitions are no longer taken granted in the wake of the US Capitol insurrection in 2021. EMBs can potentially play an important role in this process. As the following review will illustrate, independent and impartial EMBs may reduce violence,Footnote 10 help states transition from autocracy,Footnote 11 and assist new democracies to consolidate.Footnote 12 Indeed, Levitsky and Way point out that in many competitive autocratic states, elections are characterized as bitter struggles, marked by widespread abuses of power.Footnote 13 What separates these states from those characterized as democratizing is the degree to which these bitter struggles are fought fairly.

Beginning broadly, EMBs are bodies responsible for the management of elections, either in whole or in part. The management of elections concerns the organization of elections, election monitoring, and certification of election results.Footnote 14 More specifically, Mozzafar and Shedler describe three levels of electoral governance including rulemaking, rule application, and rule adjudication that can be understood as follows.Footnote 15 First, rulemaking refers to the design of the electoral game and includes rules concerning both competition and governance. This includes making rules regarding boundaries, timetables, franchise, financial regulations, election observation, and the tabulation of ballots, among others. Second, rule application concerns the organization of the game and includes tasks such as registering voters, candidates, and parties, and voting, tabulating, and reporting results. Finally, rule adjudication refers to the certification of results and dispute resolution. Determining to what degree a given EMB is responsible for the stated tasks relates to the form the EMB takes, which is a direct function of EMB design. Indeed, the three-level framework proposed by Mozzaffar and Shedler makes clear how the design of an EMB, including both political calculations, actors involved, and implementation characteristics, will decide much of its ability to produce legitimate elections. With function in mind, the discussion now turns first to the varied forms that EMBs take and follows with a discussion of EMB design.

EMBs governance varies among states with some independently administered, others controlled by the government, and others still utilizing a mixed method of both independent administration and government oversight. Independent administration is the most common governance method currently, with over 63% of states reporting an independently managed system in 2019.Footnote 16 These bodies are independent of the executive both in autonomy over conduct and finances, and in the source of their members. Newly democratized states overwhelmingly fall within this category. Governmental EMBs are organized and managed by the executive branch and largely characterize the systems in place in older, more established regimes. Finally, mixed systems consist generally of two bodies, one of which is independent of the executive and the other being located within a government branch.Footnote 17 Within each of these governance methods, the degree to which institutional constraints are actually followed varies widely. That is, an EMB which is independent on paper is not always independent in practice. For instance, data concerning EMB standards suggests that only about 53% of states reporting independent EMBs meet standards constituting the free and fair conduct of elections.Footnote 18 Therefore, beyond the method of governance, the political calculations determining EMB design can clarify the true nature of the body at work, providing greater information about the ability of these bodies to facilitate legitimate elections. The discussion now turns to this topic.

Autonomy, Capacity, and Constitutionalization

Given the wide variance in performance related to standards within the three EMB governance methods, the literature has looked to EMB design to account for differences in practice. Beyond the stated EMB governance method, design has been shown to affect EMB function as a result of the degrees of autonomy, constitutionalization (as opposed to codification in statutory law), and capacity.Footnote 19 Indeed, while the creation of an EMB may be characterized by the desire to create an autonomous body with the capability to conduct free and fair elections, oftentimes vast differences exist between stated aims and resulting institutions. During the process of EMB creation, Gazibo asserts that three relevant questions to consider include: (1) whether the process was unilateral or multilateral; (2) which group(s) prevailed in the process; and (3) in the case of negotiations, if there was one group that dominated decision making.Footnote 20 The answers to these questions characterize the power relations at play during EMB formation and can help to explain the true form of the resulting institution. In his study examining the formation of EMBs in Africa, he arrives at five categories of EMB institutions that are ultimately characterized by the drivers of the design process.Footnote 21 Beyond his discussion of the specific categories, it suffices to say that when EMB design is characterized by unilateral decision making with the dominance of one party, the likelihood of autonomy and capacity in the resulting body is low.

We are then led to ask what types of institutional design lead to an EMB with both autonomy and sufficient capacity. Beginning with autonomy, the literature, with few exceptions,Footnote 22 agrees on the notion that to conduct free and fair elections, the body organizing elections must be autonomous.Footnote 23 EMB autonomy has been variously defined. However, in practice EMBs are considered autonomous when three conditions are met. These conditions are institutional separation from the government, functional autonomy, and judicial control over the electoral process.Footnote 24 Carpenter describes bureaucratic autonomy as occurring when “a politically differentiated agency takes a self-consistent action that neither politicians nor organized group interest prefer, but that they either cannot, or will not, overturn in the future.”Footnote 25 In practice, the autonomy of an EMB can be seen as a result of two factors: (1) the formal independence of the body; and (2) the degree of partisanship/professional independence.Footnote 26

First, formal independence refers to governance method, described above. Again, referring back to the recent trend toward independently governed EMBs, the legal independence imposed by the location of the EMB outside of the executive is thought to be an important step towards achieving EMB autonomy. As noted by Lehoucq, both government and mixed-method EMBs are prone to breakdowns in legitimate electoral management when the same party controls both the executive and legislative branches.Footnote 27 However, if the goal of an independent EMB is to ensure free and fair elections that are seen and accepted as credible by all parties, formal independence alone is not enough.Footnote 28 In this vein, Pal investigates the evolution of independent EMBs in democracies, focusing on constitutionalization of independent electoral oversight.Footnote 29 The author notes that democracies that adopt independent EMBs and codify them in statutory law are more susceptible to partisan capture due to partisan appointment processes, denial of representation of smaller parties and independent voters, and manipulation of membership tenures. Alternatively, states codifying independent EMBs in their constitutions are better able to maintain truly independent EMBs for three reasons. First, constitutionalization of EMBs insulates them from partisan interference by political majorities. Second, placement of the EMB outside of the government, into what Pal describes as a fourth branch, allows for insulation of the subject matter with which the EMB deals.Footnote 30 Finally, constitutionalization of EMB independence insulates EMBs from ad hoc interventions by politicians.

Second, and related to partisan capture, the degree to which EMB members are either partisan or professional can determine the extent to which an EMB is functionally autonomous from the ruling party. Bader notes a correlation between partisan electoral commissions and unfair elections.Footnote 31 Bishop and Hoeffler, in their data collection, illustrate that the majority of EMB standards violations are related to a lack of independence or impartiality.Footnote 32 Examining the elections that took place in Latin American states since 1980, Hartlyn and colleagues illustrate positive correlations between both independent and professional EMBs and the non-partisan appointment of members, and free and fair elections.Footnote 33 A notable exception to this literature suggests that the contexts where EMBs are most necessary (those prone to violence and a rejection of electoral norms), third parties to elections (including EMBs and observers) do not necessarily need to be independent to have a positive effect on the quality of elections. The authors contend that in such contexts, a “moderate pro-incumbent bias” is more likely to produce an outcome that is acceptable to both the incumbent and the opposition.Footnote 34

Beyond autonomy, the ability of the EMB to execute the logistical task of holding elections, referred to as EMB capacity, is of great importance. Capacity, in this context, refers to the “degree to which election management organizations are stable and sustainable organizations sufficiently resourced to have the capacity to deliver elections.”Footnote 35 The specific resources included in this category might include financial and human capital while tasks are related to boundary delineation, registration of voters, administration of voting, ballot tabulation, and election reporting.Footnote 36 Indeed, independence becomes irrelevant if an EMB lacks staff and funding. Clark, in a subnational study of Electoral Registration Officers in the UK, found that localities with greater funding levels consistently outperformed their less-funded counterparts.Footnote 37 Relatedly, James and Jervier found that due to austerity measures following the 2008 financial crisis, localities in England and Wales completed less public engagement in the run up to elections, which was subsequently followed by lower voter turnout.Footnote 38 Both of these subnational studies underscore the importance of capacity in the execution of high quality, representative elections.

Apart from merely the ability to carry out an election, capacity further helps to ensure elections that are legitimate by improving confidence and decreasing clientelism. First, public confidence is increased by the technical and material capacity of EMBs. This encourages voting and confidence in electoral results. Indeed, Birch and Mulchinski find that EMB capacity building, in the form of technical assistance, was one of the factors most closely linked to electoral violence reduction.Footnote 39 Next, capacity increases confidence by clearly delineating the technical and political aspects of elections. As Pastor explains, in poor states, where elections are more difficult to conduct owing to lower levels of capacity, a technical irregularity is easily interpreted as a politically motivated effort to steal an election.Footnote 40 Where capacity is higher, elections run more smoothly, and irregularities are less frequently seen as political maneuvering. Third, regarding clientelism, EMB capacity has a dual effect: it decreases clientelism and those decreases in turn lead to further increases in capacity. As Lundstedt and Edgell explain, the presence of a strong EMB increases the cost of clientelism for voters, parties, and candidates by decreasing its utility.Footnote 41 Legitimacy of elections are thus increased due to the increased costs of clientelism in elections.

The literature review has thus far broadly asserted three main points. First, there are varied methods of governing EMBs and, recently, independent EMBs have seen an increase in utilization. Second, the design of an EMB, perhaps more than its governance method, determines the extent to which it is able to conduct free and fair elections. Finally, autonomy and capacity, influenced in large measure by both governance and design, are central to the ability of an EMB to conduct legitimate elections, increase the odds of democratic consolidation, and reduce electoral violence. Moving forward with a clear conception of the function, design, and aims of EMBs, the following section will highlight trends within the data, offering a global comparative perspective of EMBs in time, space, and institutional context.

Descriptive Context

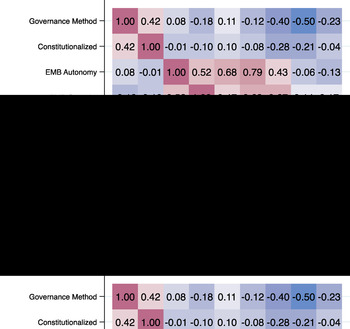

Beginning with global data on EMB governance method, we rely on data from the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA). The data record the EMB governance method in all states that hold elections and classify them as either independent, government, or mixed. Independent systems refer to states whose EMBs are independent and autonomous from the executive, organizing elections without government interference, controlling their own budgets, and consisting of members not located within the executive branch. Governmental EMBs then refer to states whose EMBs are controlled by, or located within, the executive branch. The EMB might be located within a government ministry or a local authority. Finally, mixed systems characterize those with dual structures, one organized and controlled by the executive and the other independently managed.Footnote 42 Figure 1 on the left illustrates the method of EMB governance among democracies and non-democracies at three points in time; 2006, 2014, and 2019. Two main findings stand out. First, independent EMBs are the most common method among both democracies and non-democracies. Second, while the number of democracies adopting independent bodies is increasing, the opposite is happening in non-democratic states. In 2006, 70 democracies reported independently governed EMBs. In 2019 that figure increased by 25% to 90. In 2006, 43 non-democratic states reported independent EMBs and in 2014 the number rose to 49. However, as of 2019, only 40 non-democracies report independent EMBs.

Figure 1. EMB Governance Method, 2006–2019 and Regionally in 2019

Figure 1 on the right plots current EMB rates in seven global regions.Footnote 43 Independent EMBs are the most common electoral governance method globally, outnumbering the other categories (mixed and government) in every region of the world in 2019. In Sub-Saharan Africa, only 10 states do not rely on independent EMBs and instead utilize the mixed method. The two figures above suggest that independent EMBs are numerous and increasing. However, as seen in our review of the literature, the method of governance does not tell the whole story. From there we move on to constitutionalization of independent EMBs.

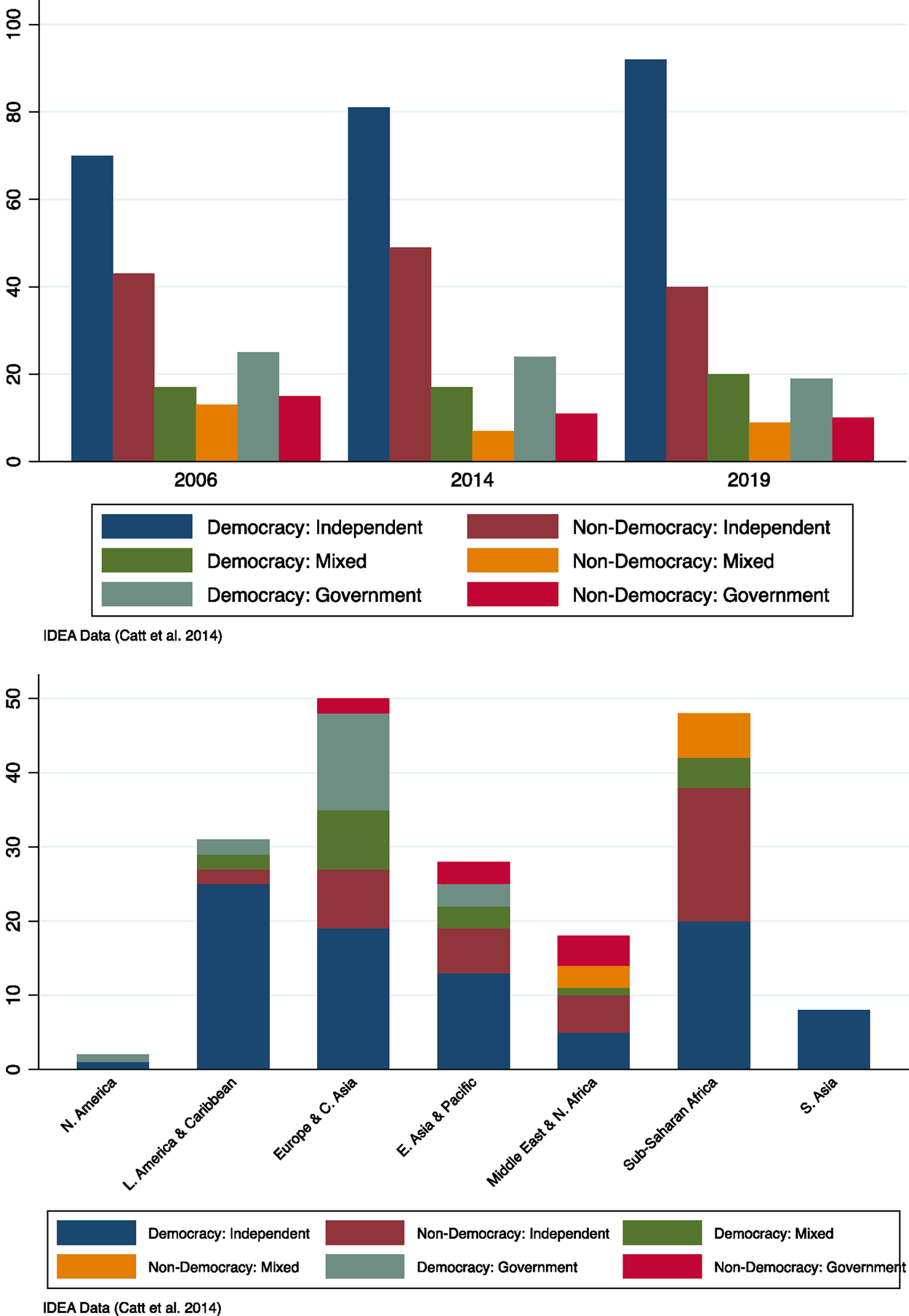

Figure 2 reports rates of constitutionalized independent electoral oversight from 1950–2013 on the left. Data on constitutionalized independent oversight are derived from the Constitute Project and record whether either an independent electoral commission, court, or both are stipulated in a state's constitution.Footnote 44 Several important findings stand out. First, the number of states with independent electoral oversight incorporated in their constitutions has increased from 11 in 1950 to 75 in 2013. The rate of increase began to pick up speed with democracy's third wave in the late 1970s. The two other lines plotted on the figure represent the number of democracies and non-democracies in each year presented. These data are derived from the Rulers, Elections, and Irregular Governance Dataset (REIGN).Footnote 45 In line with expectations, the increase in constitutional oversight in the late 1970's is mirrored by an increase in the number of democracies.

Figure 2. Constitutionally Stipulated Independent Oversight 1950–2014

Next, Figure 2 on the right plots the mean of constitutional stipulation of independent oversight in the same time period, 1950–2013, with regional standouts, Latin America and the Caribbean. This figure illustrates that much of the trend in the direction toward constitutional stipulation has been driven by Latin America in the 1970s, and by Sub-Saharan Africa in the 1990s. The findings of figures 1 and 2 provide insight into how electoral management trends have and are changing. However, as discussed in the review of the literature, while governance method and constitutionalization of independent EMBs in law are helpful toward achieving legitimate elections, the ability of EMBs to produce legitimate elections are more closely tied to their autonomy and capacity.

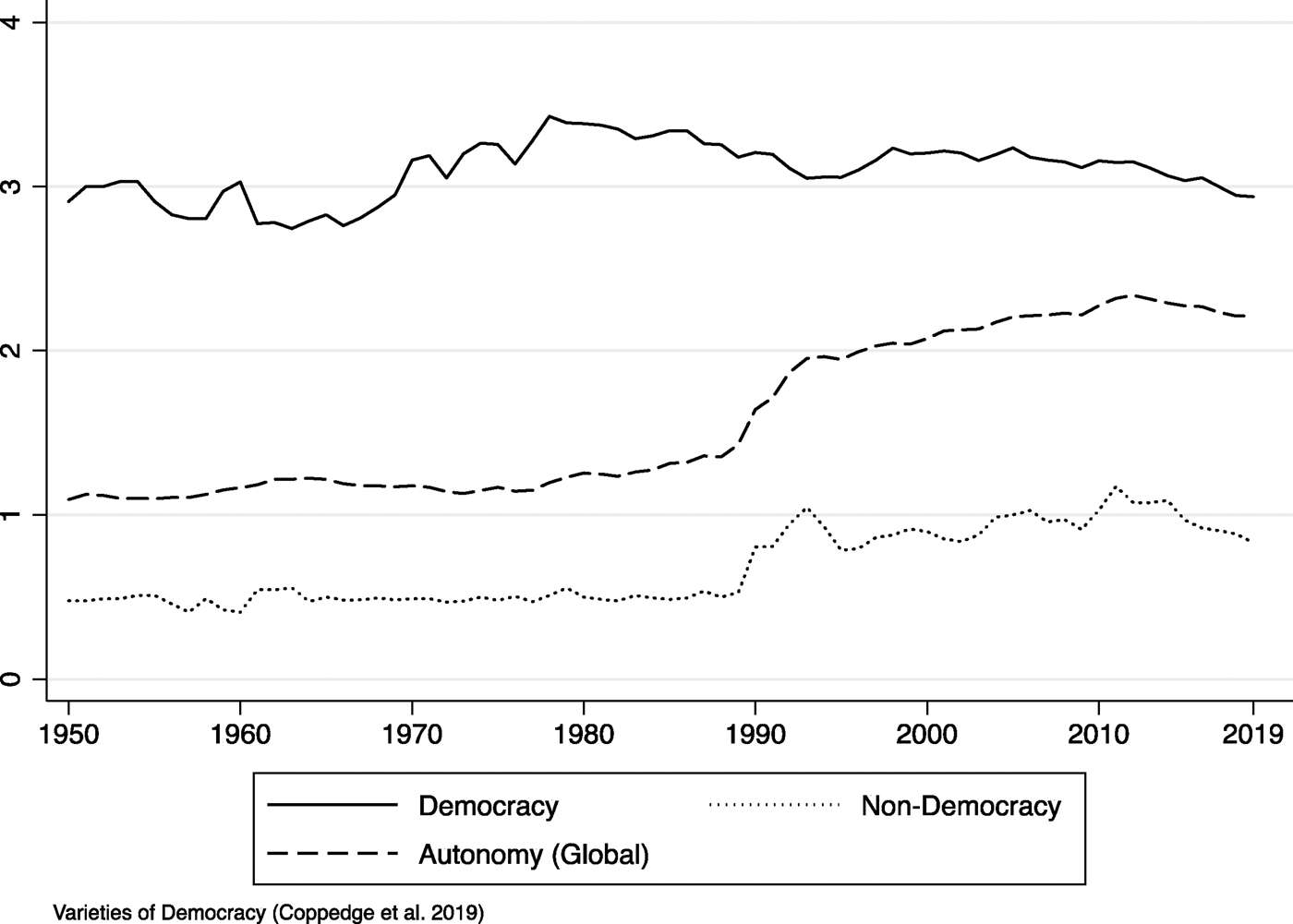

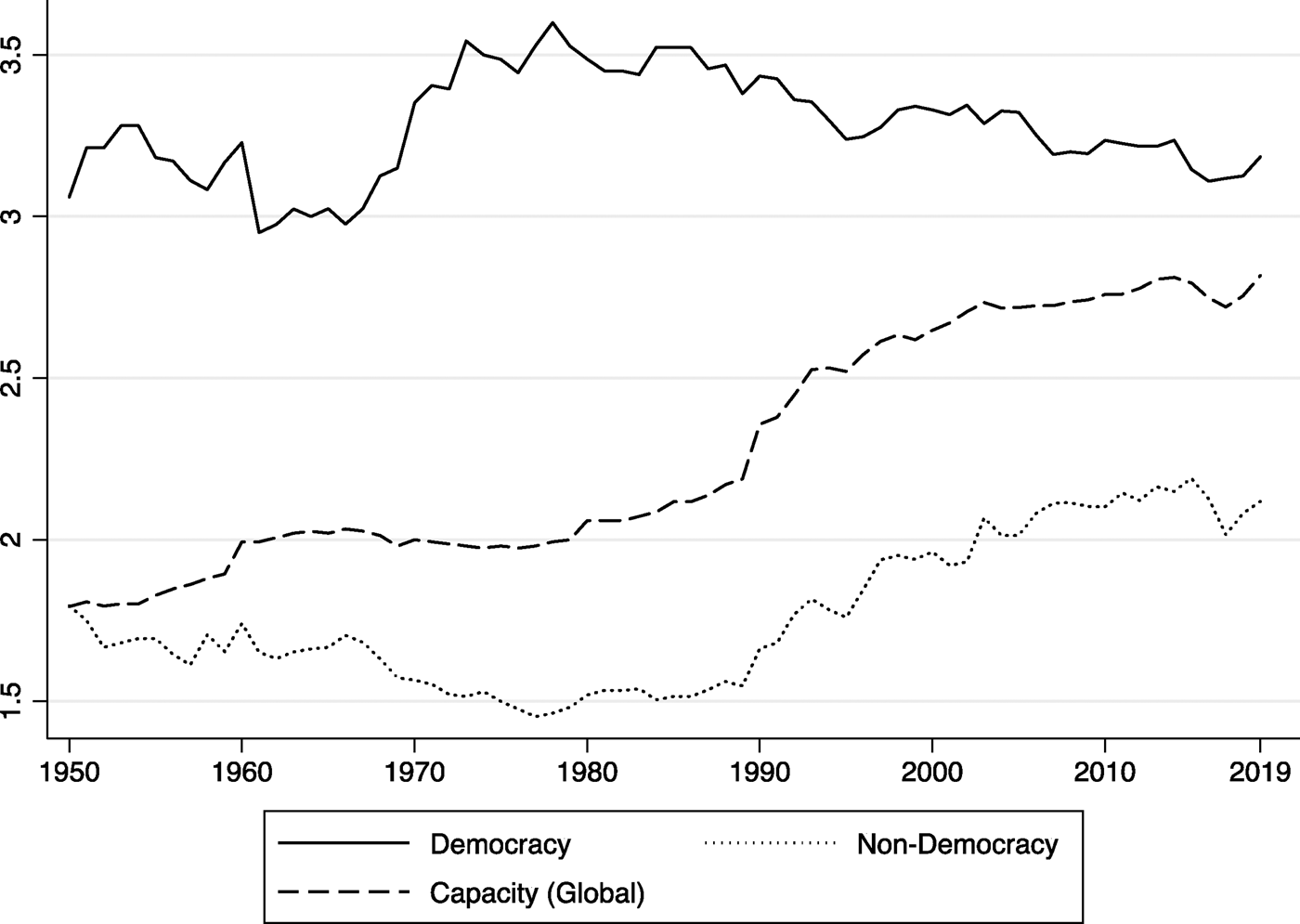

Data concerning both EMB autonomy and capacity are derived from the Varieties of Democracy Dataset (V-Dem).Footnote 46 Both measures are ordinal and recorded from expert surveys. For autonomy, the coder is asked, “does the EMB have autonomy from government to apply election laws and administrative rules impartially in national elections?”Footnote 47 The answers then range from no autonomy to full autonomy on a 5-point scale.Footnote 48 Figure 3 reports average rates of EMB Autonomy globally (dashed line), within democracies (solid line), and within non-democracies (dotted line) between 1950 and 2019. Contrary to prior figures, we do not see similar dramatic increases toward autonomous bodies that the trends toward independent governance should produce. This implies that the global trend toward both constitutional stipulation and independent EMB adoption is having little effect on the overall autonomy of election management. This may indeed be the case; as Bishop and Hoeffler suggest, the overall quality of elections has declined over time.Footnote 49 Also made clear in the figure is a vast difference in rates between democracies and non-democracies. Democracies vastly outperform non-democracies in EMB autonomy, as one would expect.

Figure 3. EMB Autonomy 1950–2019

Finally, we examine capacity over time. The capacity measure is derived from V-Dem and is also collected from expert surveys. The survey asks the coder, “does the EMB have sufficient staff and resources to administer a well-run national election?”Footnote 50 The measure is ordinal, recorded on a 5-point scale ranging from insufficient capacity to full capacity. Figure 4 examines EMB capacity in the period 1950–2019. Three lines are plotted: global mean of EMB capacity (dashed line), mean of EMB capacity in democracies (solid line), and the mean of capacity in non-democracies (dotted line). Unlike the prior figure examining autonomy, there is a clear upward trend in EB capacity where the measure, in democracies, begins to surge in the late 1970s, as more states begin to democratize and allot resources to electoral management. Within non-democracies globally, a smaller increase in capacity can be seen in the 1990s.

Figure 4. EMB Capacity 1950–2019

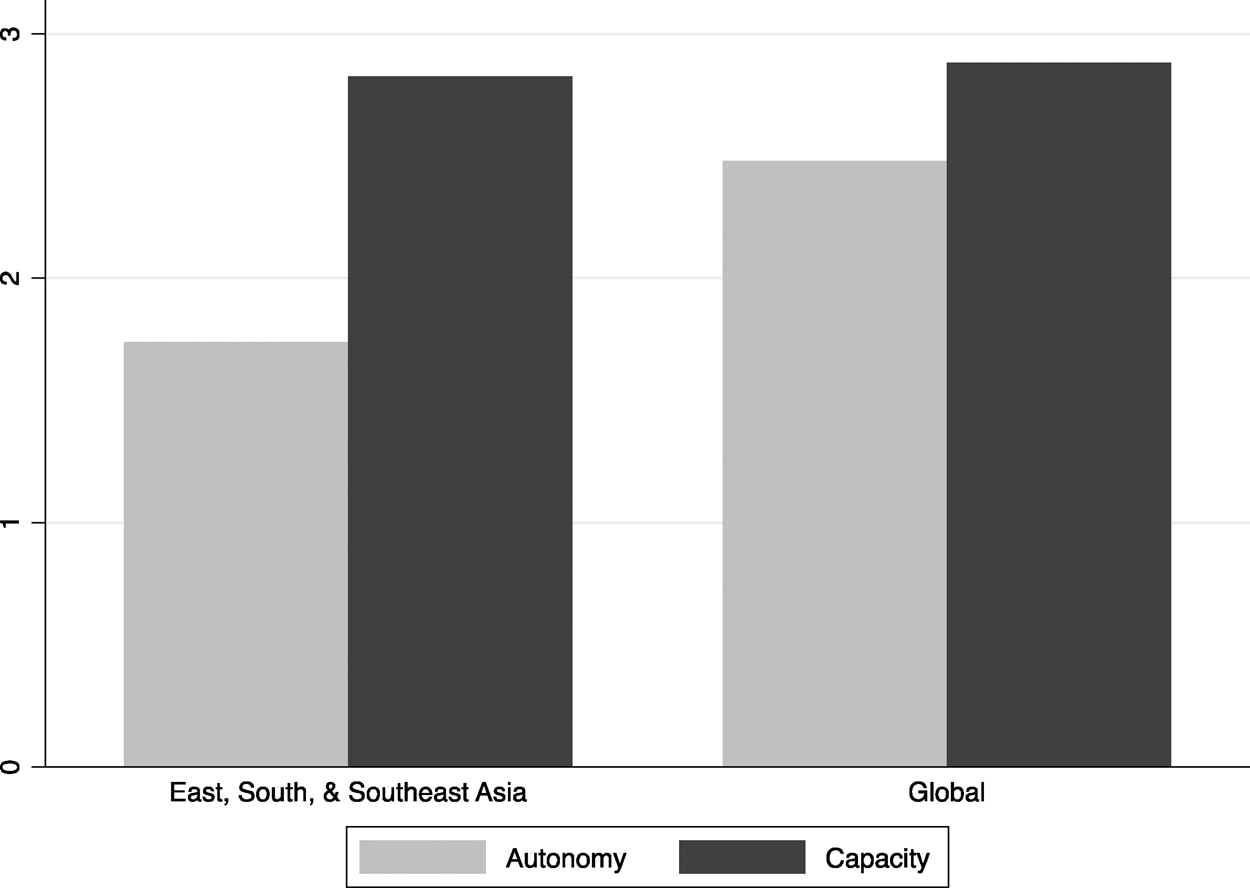

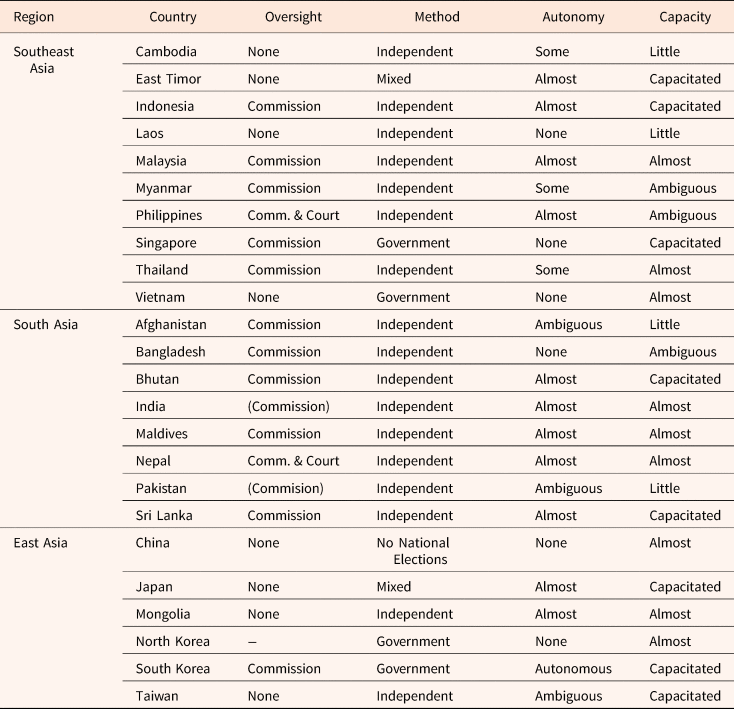

Given that this Special Issue is focused on Asia we also present descriptive data concerning autonomy and capacity in this region specifically. Figure 5 examines EMB capacity and autonomy within Asia (including East, South, and Southeast Asia) comparing these measures to their global means (excluding these regions). As illustrated in Figure 5, the measures of autonomy and capacity in Asia are somewhat paradoxical in a global perspective – the reverse of the pattern in other democratizing regions. Only half (13) of the states in the region are ranked as autonomous or almost autonomous (most in the latter category) while many more (17)Footnote 51 are ranked as capacitated or almost capacitated – suggesting that EMBs are efficient but must operate within tighter bounds. Examining governance method, the region follows the global trend with an overwhelming number states having independent bodies.

Figure 5. EMB Autonomy and Capacity in Asia

Data and Empirical Strategy

In this section, we present the results of twelve logistic regressions utilizing a global sample of 153 states from 1950–2019. Much of the data utilized has been described in detail above. We briefly review the data sources and describe the empirical strategy.

Our empirical analysis is aimed at determining the extent to which the trends, described above, have resulted in variance in EMB efficacy. The notion of efficacy may be conceptualized in several different ways, including perceptions of legitimacy, the presence of electoral violence, or judgments by the international community concerning freedom and fairness. In the interest of obtaining widely generalizable results, we chose to rely on measures of electoral confidence and electoral characteristics. Beginning with concern over the freedom and fairness of elections (Table 2), the dependent variable is a dichotomous measure where 0 denotes no widespread concern over freedom and fairness and 1 denotes the existence of widespread concern. The data are derived from the NELDA dataset.Footnote 52 Next, turning to a measure of electoral characteristics, Table 3 utilizes a dichotomous measure, also from the NELDA dataset, concerning violence surrounding an election where 0 is no violence and 1 is widespread violence. Importantly, for both dependent variables, a negative relationship signifies the absence of a widespread concern or widespread violence. As both of our dependent variables are binary, we utilize logistic regression, clustering standard errors by country code in an effort to reduce heteroskedasticity.

Our independent variables are focused on both formal design and practical function. First, focusing on a measure of design, the descriptive section illustrated the rise in constitutionalization of independent EMBs. We therefore begin with a measure of constitutionalization of independent oversight from the Constitute Project.Footnote 53 This is a dichotomous measure recording a 1 in all states where independent electoral oversight (either a court, commission, or both) is stipulated in the constitution, and 0 where absent. Second, focusing on the practical function of EMBs, we rely on two measures from the Varieties of Democracy dataset (V-Dem), autonomy and capacity. Autonomy is an ordinal measure from V-Dem, where 0 is no autonomy and 4 is full autonomy. Third, capacity is also an ordinal measure from V-Dem, where 0 is no capacity and 4 is full capacity.Footnote 54

Further, given that we see wide variance in both stated aims (governance method and constitutionalization) and performance (autonomy and capacity) among regime types, we further include an indicator of regime type, labeled democracy. This is a binary measure from the REIGN dataset, relying on a minimal procedural definition of democracy where 1 = democracy and 0 = nondemocracy.Footnote 55 However, as we discuss in the conclusion, there is an outstanding question of causal direction that needs further explanation: to what extent is democracy, even in our very binary and partly static measure, a function of EMB performance, the dependent variable? Finally, to determine if the effects of constitutionalization, autonomy, and capacity differ by regime type, we further include interactions of constitutionalization, autonomy, and capacity with democracy. Simply put, democracies, by definition, have more competitive elections, than do non-democracies and we should thus expect that EMB characteristics will have different ramifications in these states. Therefore, all 12 models utilize the same five main independent variables. These independent variables include: Constitutionalization, Autonomy, Capacity, Democracy, and an interaction term (constitutionalization, autonomy, or capacity X democracy).

We control for four measures, theoretically linked to electoral characteristics, in all 12 models: of Latent Judicial Independence, Footnote 56 the natural log of GDP per capita,Footnote 57 regime spell, and degree of trade openness from KOF Globalization dataset.Footnote 58 Beginning with latent judicial independence, we expect that a more independent judiciary will be negatively correlated with both concern and electoral violence. Next, more developed states are associated with lower levels of electoral violence and concern over freedom and fairness in elections. For regime spell, we include a count of the years that a state has remained one consistent regime type to proxy for consolidation. Here we expect more consolidated regimes to be associated with less violence and less electoral concern. Finally, we include trade openness, capturing trade volume relative to GDP, as a proxy for both social and monetary globalization, with the expectation that more globalized states will have less electoral violence and less concern regarding freedom and fairness.

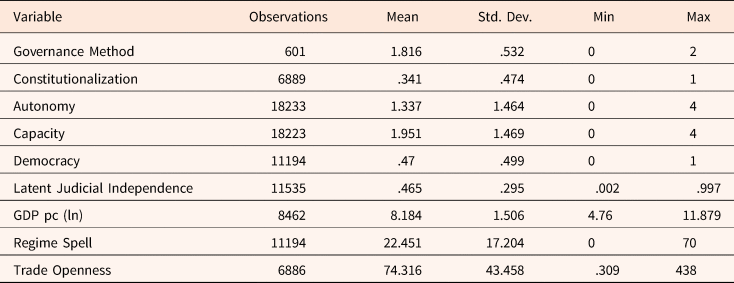

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics concerning the variables utilized in the following analysis. As seen in the table, the data on governance method from IDEA are only available for a small number of observations. As a result, we rely on the measure from the Constitute Project recording whether there is constitutionally stipulated independent oversight in a country year.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics

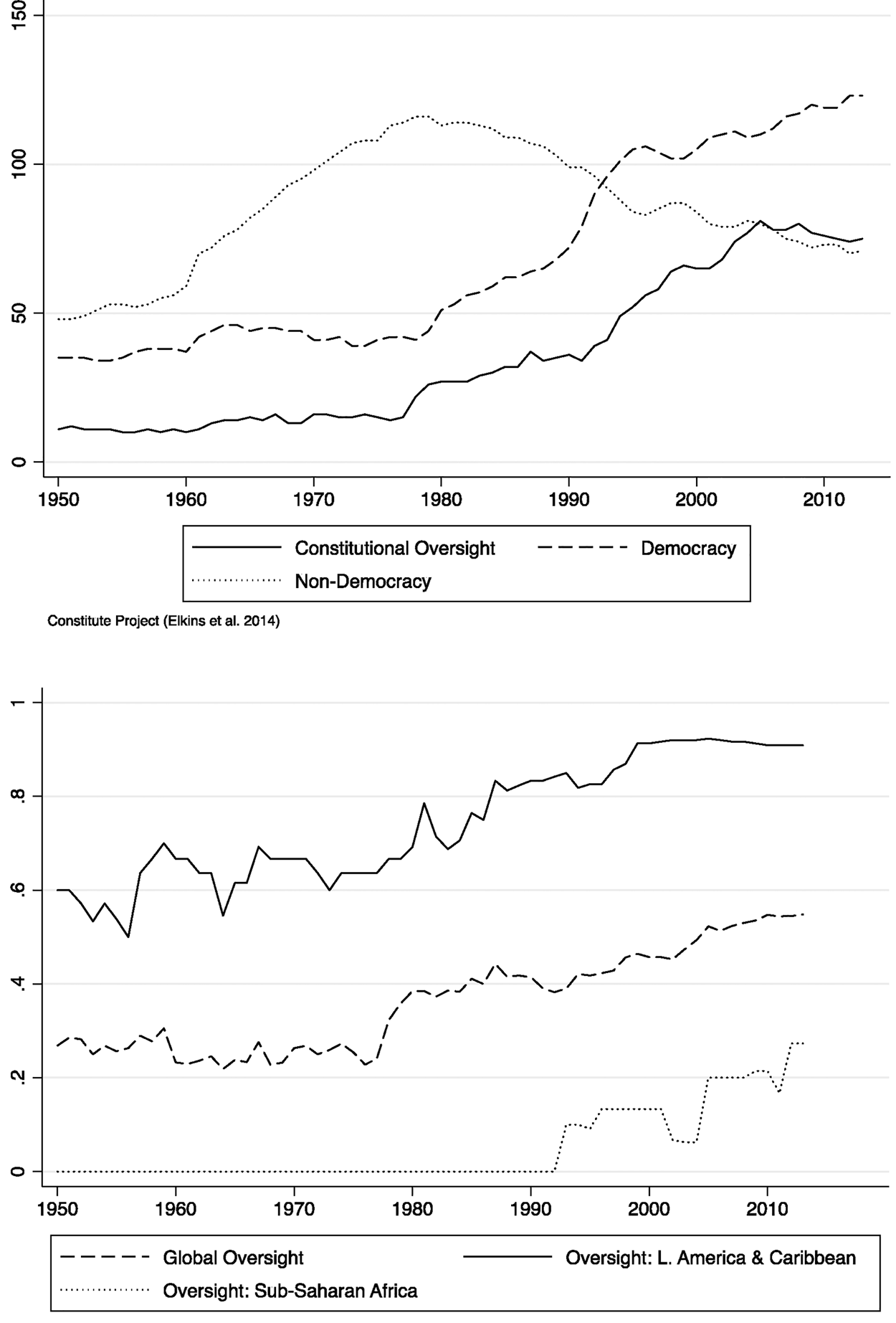

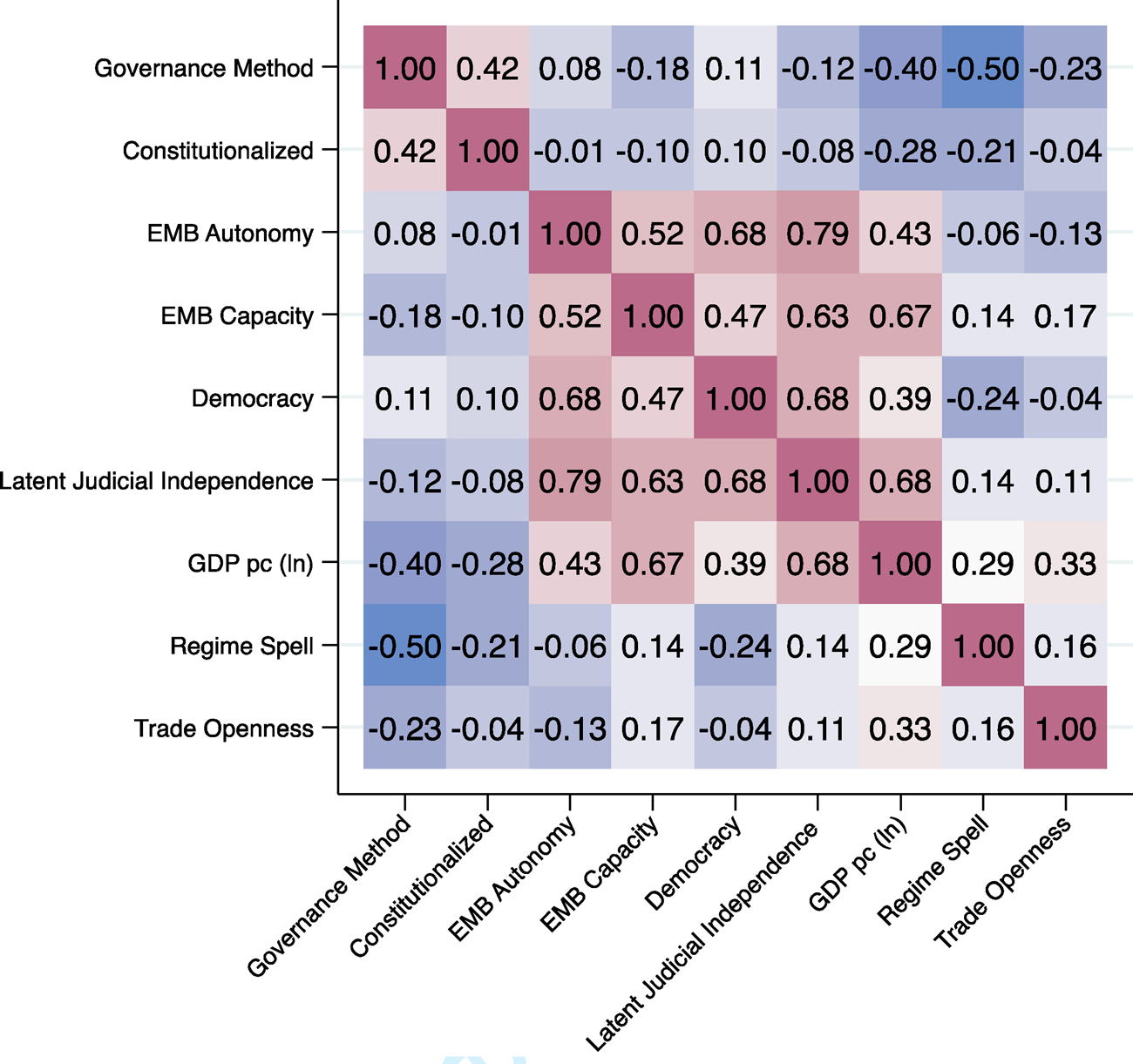

Figure 6 provides a correlation matrix heat map, including all variables utilized in the analysis, with the exception of interaction terms. Several interesting trends are evident. First, governance method is correlated with constitutionalization of independent electoral oversight at a rate of .42, meaning that less than half of all states with independent EMBs have this stipulated in their constitutions.Footnote 59 Second, method of governance is correlated at only .08 with autonomy. In short, the stated governance method has little to do with autonomy in practice. Interestingly, latent judicial independence is highly correlated, at .78, with autonomy, suggesting that states with higher levels of judicial independence are more likely to see autonomous EMBs. Finally, capacity is correlated with level of development (GDP pc (ln)) at .64, suggesting that wealthier states have EMBs with greater capacity.

Figure 6. Correlation Matrix Heat Map

Results

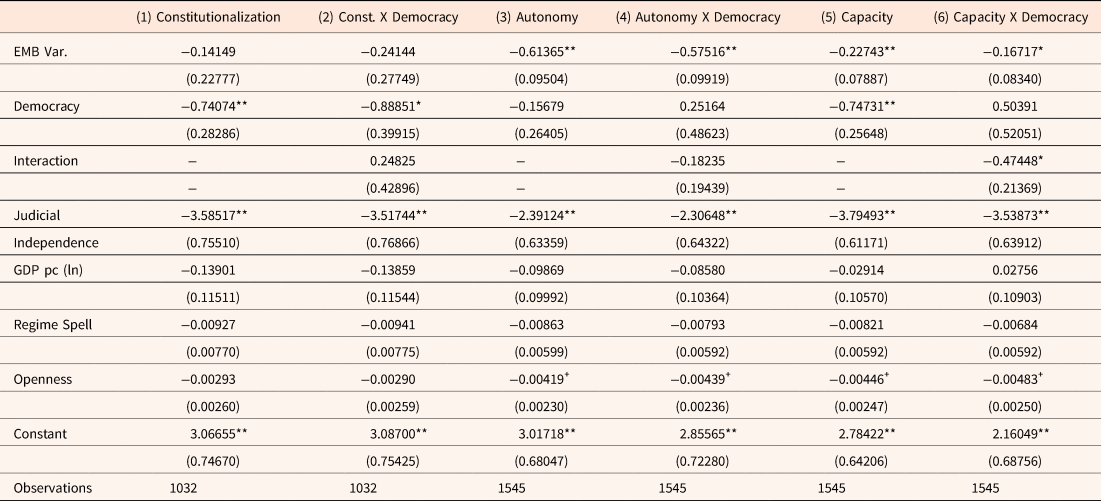

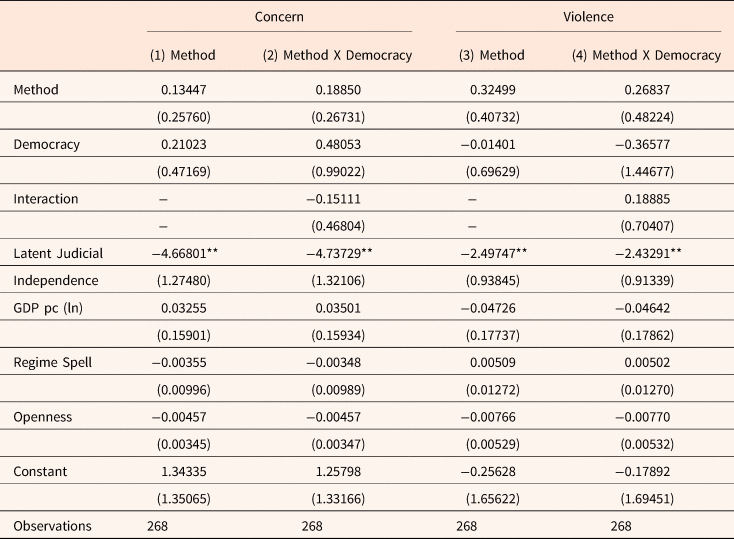

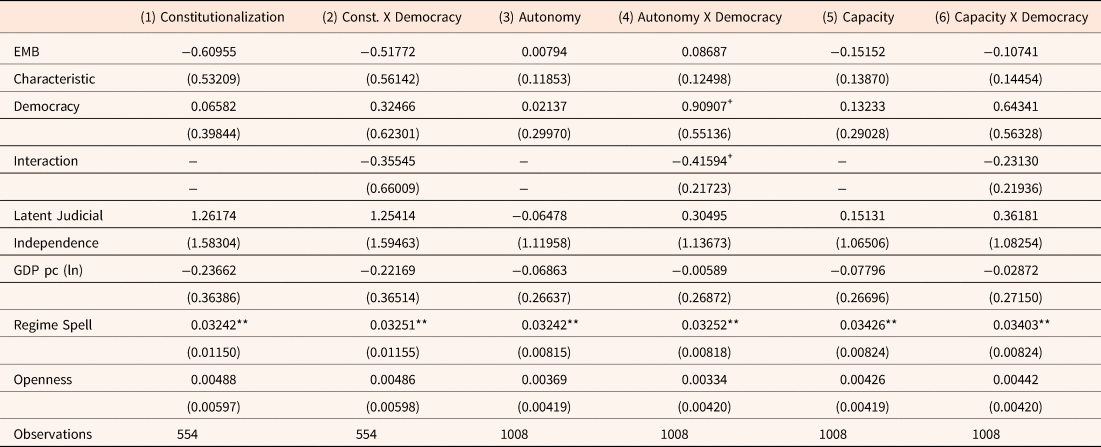

Our regression analyses present the results of two tables, each examining a different dependent variable. Table 2 examines concern in elections and Table 3 examines the existence of widespread electoral violence. Given the coding of the dependent variables (where 1 denotes the presence of a negative election characteristic and 0 its absence), negative coefficients signal a positive effect of the EMB characteristic examined. Beginning with Table 2, the results of six logistic regressions are presented. Models 1, 3, and 5 are naïve models, excluding the interaction term, and models 2, 4, and 6 examine the interaction of either autonomy, capacity, or constitutionalization with democracy. Beginning with model 1, we examine the effects of constitutionalization and democracy on concern. Constitutionalization displays a negative, though not significant, coefficient with a p-value of .5. Democracy, however, is both negative and significant at the .01 level. This suggests that democracy is associated with a greater amount of confidence in elections more generally.

Table 2. Concerns about Freedom and Fairness: EMB Characteristics & Regime Type

Standard errors in parentheses.

+ p < .1, * < .05, ** < .01.

Table 3. Electoral Violence: EMB Characteristics & Democracy

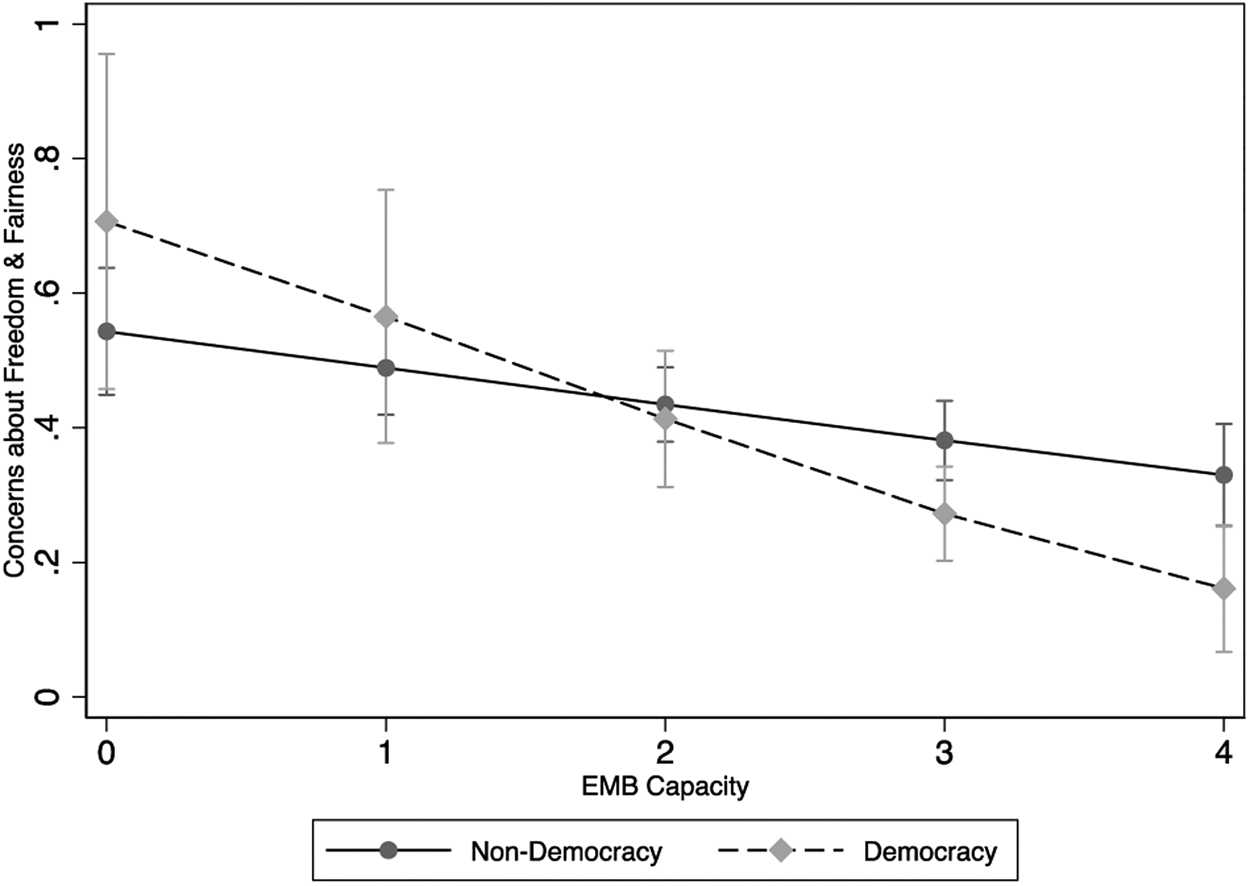

In model 2, examining the interaction of democracy and constitutionalization, the constitutionalization term again fails to illustrate substantive results. The democracy term, however, maintains its negative and significant coefficient. This suggests that democracies that do not constitutionalize independent oversight are correlated with greater confidence in elections (less concern) than democracies that constitutionalize independent oversight or those that lack independent oversight. The interaction term, while positive, is not significant. Moving to model 3, the autonomy coefficient is negative and significant at .01 level, suggesting that states with more autonomous EMBs are correlated with greater confidence (less concern) in elections. The democracy coefficient here, while negative, fails to achieve significance at a p-value of .5. Turning to model 4, and examining the interaction of democracy and autonomy, we can see that the autonomy and democracy terms maintain their relationships from the naïve model. The interaction, however, again fails to achieve traditional levels of statistical significance. Surprisingly, the negative and significant coefficient of the autonomy measure suggests that autonomous EMBs are correlated with lower levels of electoral concern (more confidence) in autocracies than in democracies. Next, model 5 separately examines the effects of capacity and democracy on electoral concern. Both the capacity and democracy coefficients are negative and significant at the .01 level. In short, both democracy and capacity are correlated with greater levels of electoral confidence (less concern). Finally, in model 6 we examine the interaction of capacity and democracy. Here, the capacity term maintains its negative and significant relationship and the democracy term loses significance. Further, the interaction term is negative and significant at the .05 level. The results of this model suggest that capacity is associated with less electoral concern in democracies. However, increases in capacity are associated with less electoral concern in all regimes. To investigate this further, Figure 7 plots the marginal effects of the interaction in model 6.

Figure 7. Marginal Effects of Capacity & Democracy on Electoral Concern

Figure 7 plots the effects of the interaction of EMB capacity and democracy on concerns over freedom and fairness of elections. The y-axis represents plots the rate of concern, from 0 to 1, and the x-axis plots the level of EMB capacity. The dotted line represents democracies and the solid line, non-democracies. Moving from the lowest levels of capacity, at 0, to the highest levels at 4, there is a clear downward trend in both democracies and autocracies in the rate of concern over freedom and fairness in elections. In democracies, moving from the lowest levels of capacity (0) to the mean of capacity (1.95) the rate of concern drops from 70% to about 42% (~50% change). In non-democracies, the same change from the minimum to the mean results in a change of about 20%, from 54% to 44%. However, while the coefficient of the interaction in model 6 is negative and significant, as Figure 7 shows, confidence intervals overlap through the range of capacity, suggesting little substantive differences between democracies and non-democracies. Indeed, while the rate of change appears greater in democracies, this has less to do with variance in confidence at different levels of capacity and more to do with the relatively higher rates of concern about freedom and fairness in democracies when capacity is low.

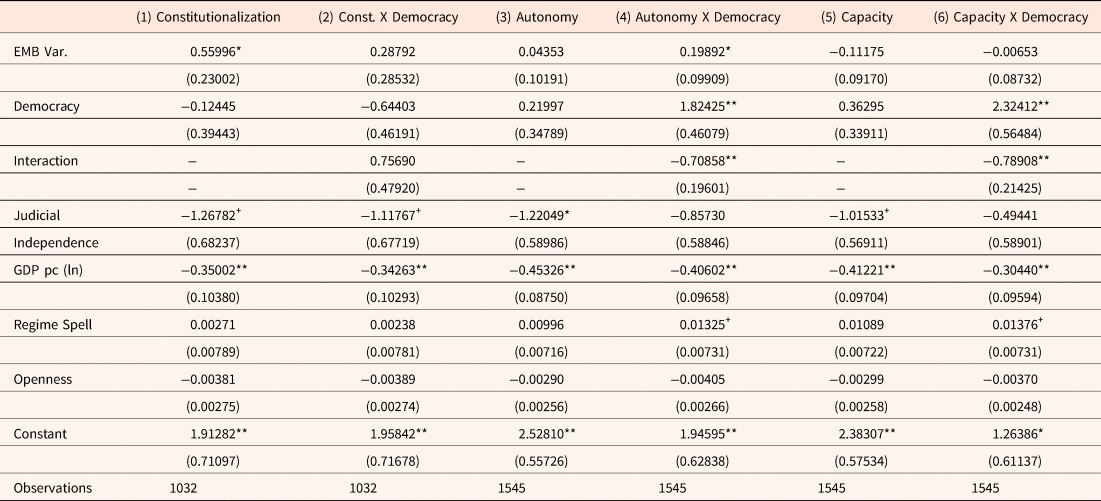

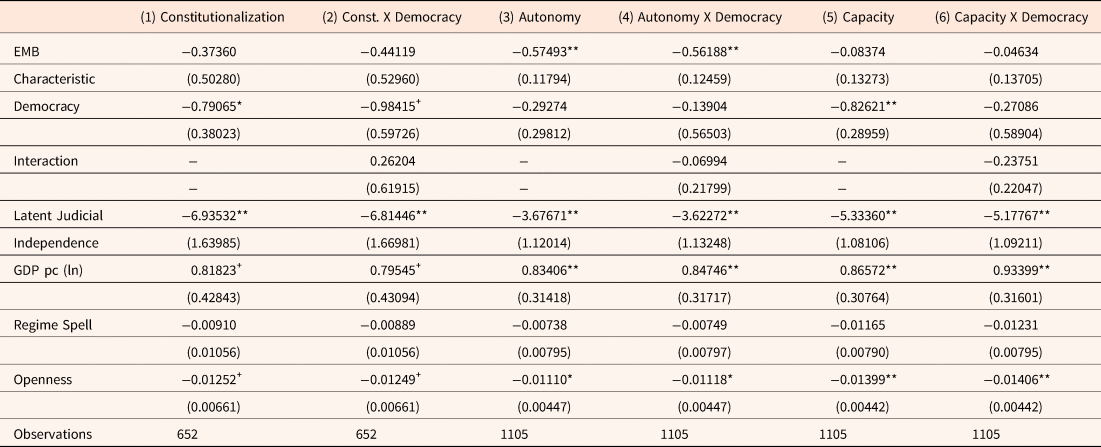

Turning to Table 3, examining the existence of widespread electoral violence, the format mirrors that in Table 3. Models 1, 3, and 5 illustrate naïve models, presenting the coefficients for constitutionalization, capacity, autonomy, and democracy separately. Models 2, 4, and 6 then present the results for the interactions of the EMB characteristic variable and democracy.

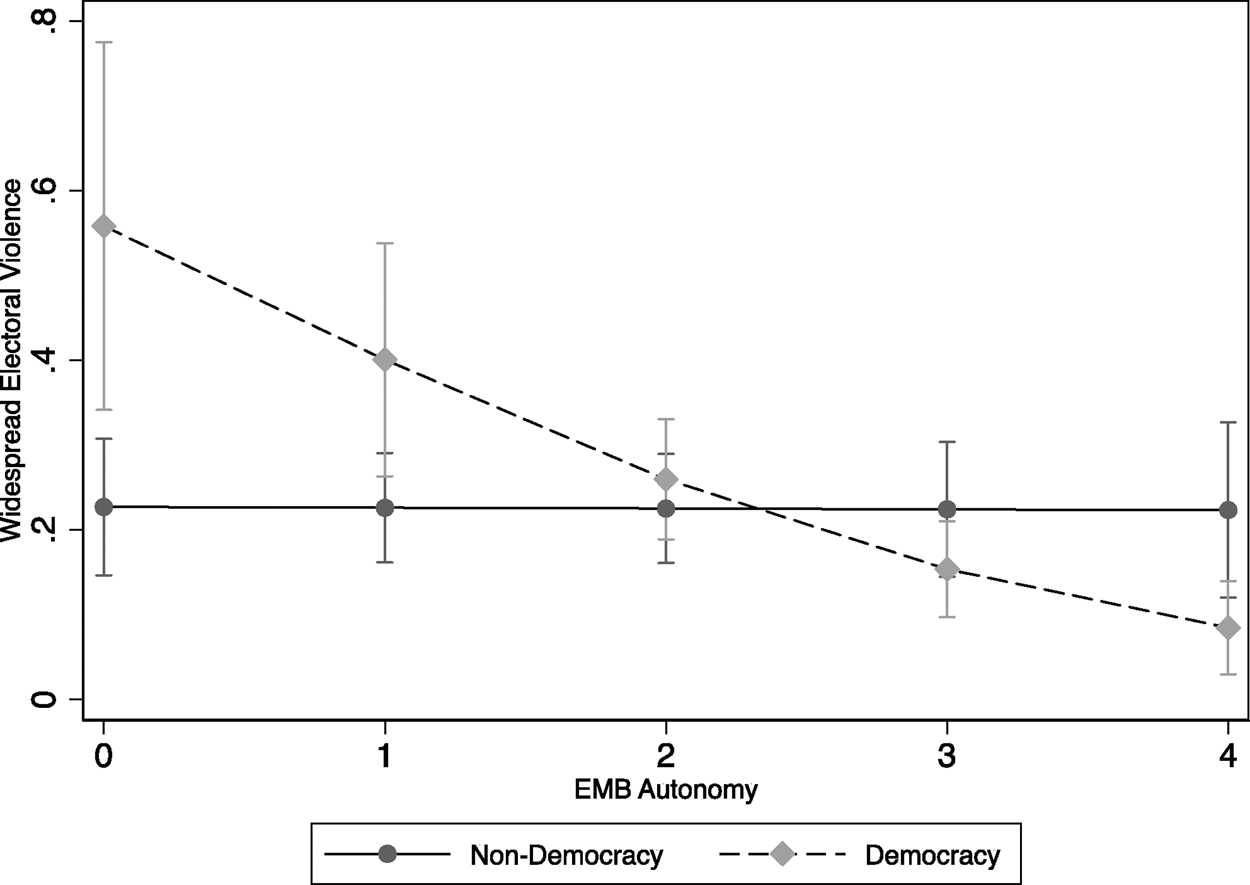

Beginning with model 1, the coefficient for constitutionalization is positive and significant at the .1 level suggesting that constitutionalization of independent EMBs is associated with greater levels of electoral violence. Next, the coefficient for democracy is negative but fails to achieve statistical significance. Then, in model 2 examining the interaction of democracy and autonomy, neither relevant term nor the interaction achieves statistical significance. Continuing, model 3 examines the effects of autonomy and democracy separately. Coefficients for each term on their own, while positive, fail to illustrate any substantive results. Turning to model 4 and examining the interaction of autonomy and democracy, the coefficients for both terms are positive and significant, and the interaction term is negative and significant. The results of this model suggest that when autonomy is low, democracies see greater levels of electoral violence. Additionally, as autonomy increases, violence decreases in both autocracies and democracies. To further illustrate the effects of the interaction, figure 7 plots the marginal effects.

In Figure 8, the y-axis represents the rate of widespread electoral violence, from 0–1. The x-axis represents the range of values of EMB autonomy where 0 is no autonomy and 4 is fully autonomous. The solid line plots the changes in non-democracies over the range of autonomy and the dashed line does the same for democracies. Beginning at the lowest levels, where an EMB is completely subservient to the regime, the rate of violence in democracies is higher than in non-democracies. When autonomy is 0, the rate of violence in democracies is about 0.55, decreasing to about 0.44 at the global mean of autonomy (1.3). As is evident in the figure, this rate sees little change in non-democracies, illustrating about a 0.22 rate at 0 and a 0.22 rate at the mean. Further, as the figure illustrates, beyond the lowest quartile of autonomy, confidence intervals overlap suggesting little substantive difference in electoral violence among democracies and non-democracies at higher rates of EMB autonomy.

Figure 8. Marginal Effects of EMB Autonomy & Democracy on Widespread Electoral Violence

Moving to model 5, neither the EMB capacity nor democracy coefficients illustrate substantive results. Alone, the model suggests that neither factor on its own is correlated with electoral violence. Moving to model 6 however, the democracy term illustrates a positive and significant effect, suggesting that when capacity is low, democracy is correlated with higher rates of electoral violence. Next, the interaction, similar to model 2, illustrates a negative and significant effect. In short, the positive effect of the democracy measure on the rate of violence decreases as capacity increases. Figure 8 details this interaction by a plotting of its marginal effects.

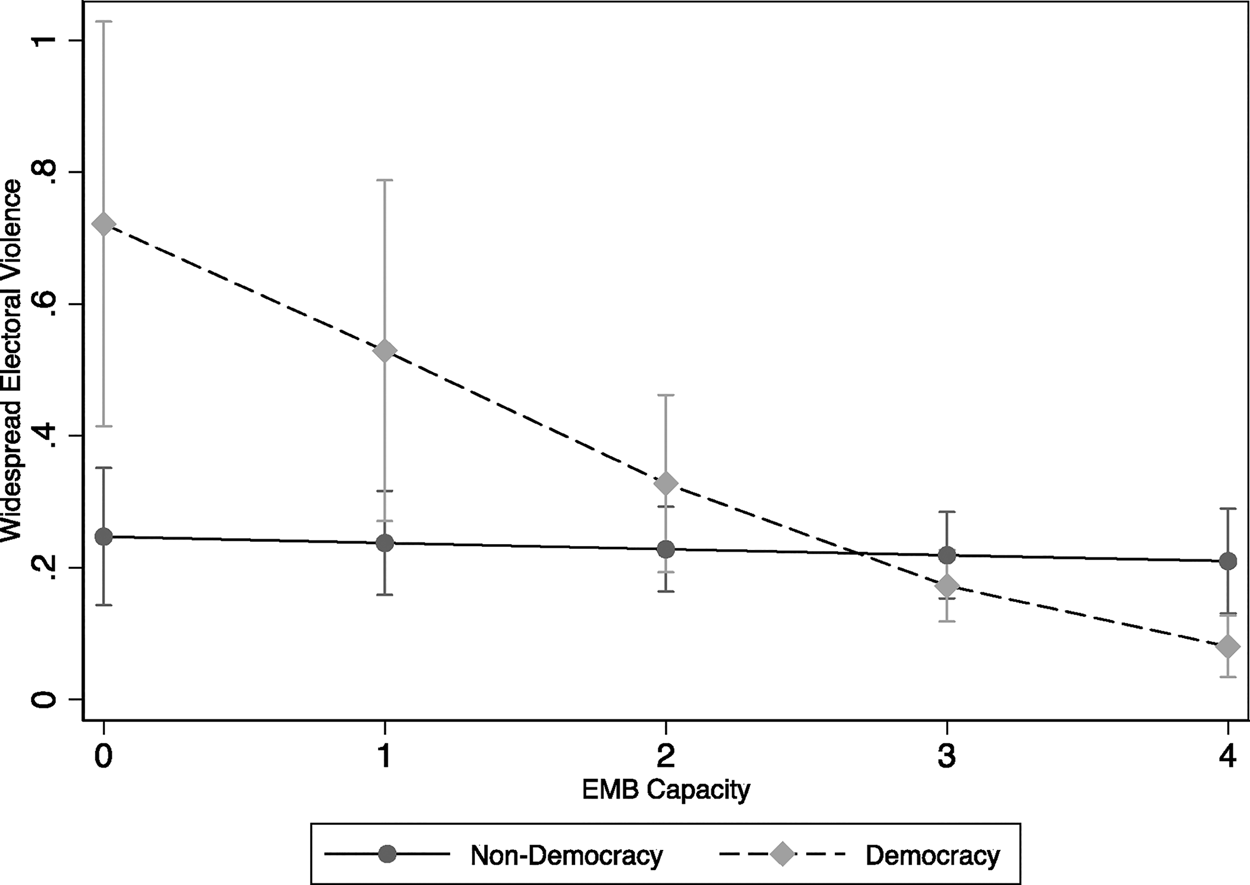

In Figure 8, the y-axis represents the rate of electoral violence, the x-axis illustrates the range of EMB capacity, moving from low to high (left to right), the dashed line illustrate democracies, and the solid line, non-democracies. Similar to Figure 9, vast differences in rates of violence are evident among democracies and non-democracies at the lowest levels of capacity. Moving from the minimum (0) to the global mean of capacity (1.95) democracies see a decrease in electoral violence of over 76% (from 0.72 to 0.32). This same increase in capacity results in an approximate 9% change in non-democracies (from 0.24 to 0.22). Beyond the mean of capacity, confidence intervals overlap, suggesting little substantive differences in electoral violence among democracies and autocracies at different levels of EMB capacity.

Figure 9. Marginal Effects of EMB Capacity & Democracy on Widespread Electoral Violence

Turning to control variables, several interesting findings stand out. Latent judicial independence is negative and significant in the majority of the twelve models presented. This is expected: as the literature review suggests, judicial control over the electoral process is seen as central to guaranteeing autonomy of EMBs in practice.Footnote 60 Third, GDP fails to illustrate substantive results in Table 2, but is robustly negative and significant in Table 3. This again is expected as clear patterns have been established in the literature between violence and development, while the same is less related to electoral confidence. Regime duration fails to produce robust results with the coefficients flipping between positive and negative in the tables and failing to achieve significance. Finally, trade openness is negative but not robustly significant throughout the models, suggesting that higher trade volume is correlated with better quality elections.

The appendix includes three robustness tests that further examine the results presented in the main analysis. Results in the appendix are robust to those in the main analysis. Table A2 examines the governance method as a primary independent variable, and Tables A3 and A4 reproduce tables 2 and 3 with the inclusion of fixed effects. Governance method alone has no effect on either concern or violence, confirming results presented related to constitutionalization of independent EMBs. Second, the results of an examination of fixed effects are largely consistent with those in the main analysis, confirming that the findings presented are not the result of within country variation alone.

Conclusion

Following the third wave of democratization, the number of EMBs has expanded dramatically, especially in the democratizing regions of Latin America and the Caribbean, Sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia – although with mixed patterns in both South-East Asia and East Asia. Between 2006 and 2019, the number of IECs worldwide rose from 113 to 130, with 15 of 24 Asian states possessing an IEC - tracking now the global average.Footnote 61 EMBs that are autonomous in practice are largely found in democracies, although only a slight majority of states enshrine these institutions in their constitutions. Moreover, there is a suggestion of Asian exceptionalism with the region hosting EMBs that tend to be restricted in their autonomy, while being highly capacitated.

In terms of their effectiveness, the results are mixed. They highlight several questions including the efficacy of EMBs (whether they advance free and elections), the attributability of performance to design (efficacy of constitutionalized independent EMBs versus those stipulated in statutory law), and the degree of endogeniety at work in the relationship between regime type and EMB performance. We attempt to shed light on these questions by highlighting trends in the data concerning regime characteristics, temporal dimensions, and regional associations. We find that while both autonomy and capacity are associated with lower levels of electoral violence, only capacity appears to be associated with increased confidence in elections. Additionally, the constitutionalization of independent EMBs does not illustrate any substantive effects on either electoral confidence or violence.

The relationships between EMBs and resulting electoral characteristics are therefore conditional on the nature, rather than form, of EMBs. Merely establishing an independent or constitutionally-enshrined EMB does not provide – in the short-term at least – expected benefits. Rather, it is EMBs that are graded as autonomous or possessing capacity that have the greatest effect on reducing electoral violence. The key policy challenge in many newly democratizing states, where EMB autonomy and capacity is low, is how to improve the robustness of these institutions.

This point returns us to the question of endogeneity: do free and fair elections, facilitated by autonomous and capacitated EMBs, aid in democratic transitions and increase democratic longevity? Or instead, do stable democracies – as captured by our research design – help build independent and autonomous EMBs? Or is it both? This requires further research. However, our findings identify a key explanatory variable that may help to illustrate the causal and self-reinforcing mechanism here—courts. Latent judicial independence illustrates a robust negative relationship with both violence and concern about free and fair elections. Thus, a possible causal pathway, which requires further investigation, is that healthier democracies produce more space for robust judicial review, which in turn strengthens the hand of EMBs, and so bolsters democracy – and so the virtuous cycle repeats again. The recent overturning of the 2019 election results in the fledgling democracy Malawi by its constitutional court is a pertinent example.Footnote 62 The court, despite facing considerable pressure and political threats, found that the Malawi Electoral Commission (MEC) failed to address complaints before announcing results and ordered new elections to take place within 150 days. The new elections resulted in an opposition victory and peaceful transfer of power.

The complex relationship between democracy and EMBs and the role of courts deserves thus further empirical and scholarly inquiry. Political science literature is more focused on the relationship between EMBs and government, and legal literature on courts and elections. These results highlight the role that courts can play in assuring free and fair elections by empowering EMBs. If EMBs are to fulfil their role in Asia though, the highly varied robustness of judicial review across the regionFootnote 63 may be a good place to start.

Appendix

Table A1. Overview of States in Southeast, South, and East AsiaFootnote 64

Table A2. Governance Method, Democracy, and Electoral Characteristics

Table A3. Constitutionalized Independence, Autonomy, & Capacity on Electoral Concern, Fixed Effects

Table A4. Constitutionalized Independence, Autonomy, & Capacity on Electoral Violence, Fixed Effects

Author Biographies

Malcolm Langford, Professor of Public Law, University of Oslo. Director, Centre for Experiential Legal Learning (CELL) and formerly Co-Director, Centre for Law and Social Transformation, Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI) and University of Bergen.

Rebecca Schiel, Postdoctoral Fellow, School of Politics, Security and International Affairs (SPSIA), University of Central Florida and CMI.

Bruce M. Wilson, Professor, SPSIA, University of Central Florida. Associated Research Professor and Project Leader, Impact of the Human Right to Water, CMI.

This article was partly financed by NRC Forskerprosjekt-FRIHUMSAM project number 263096): P.I. Bruce M. Wilson and by the University of Central Florida Preeminent Postdoctoral Program (P3) grant number 0000007509; P.I. Bruce M. Wilson.