Article

Art libraries are more than buildings; they are places for artistic inspiration that hold real value for studio art students. However, unlike art history courses, which often have a research component, the relationship between studio practice and the art library is not always readily apparent. Art librarians themselves, especially those with instruction responsibilities, must get creative when engaging art students and faculty with library resources.

In fall of 2021, an art librarian and a studio art professor began a collaboration that evolved over the course of three semesters. Inspired by the book spine poetry created by artist Nina Katchadourian and the use of chance as an artistic principle, they created a lesson plan that fosters serendipitous encounters and demonstrates the art library's potential as a space for creative exploration by leveraging art students’ preference for browsing as an information seeking strategy. After participating in the lesson, students’ artwork showed a marked improvement in terms of expressive and thematic content and many students used the ideas they explored in the library throughout the semester and beyond as the basis for artworks.

Art students’ preference for browsing

Artists and art students have a marked preference for browsing the stacks as an information seeking strategy. This behavior was first noted by Derek Tonye in his article “A philosophy for Falmouth” in 1977 and runs steadily throughout the literature to the present.Footnote 1 More specifically, art students prefer browsing for inspiration, specific visual elements and materials and techniques.Footnote 2 Much of the literature also equates browsing with the joys of serendipity. As described by one participant in Tami Echavarria Robinson's 2014 study, “It's like a spark, and certain things change when you think about it further.”Footnote 3

While art students’ predilection for browsing is well documented in the literature, practical ways librarians can create opportunities for serendipitous discovery through browsing, although increasing, are still relatively rare. This is not surprising. Searching is more easily broken down into a teachable, step-by-step process. How does one teach serendipity?

Chance as artistic practice

Serendipitous browsing relies, at least to a certain extent, on the principle of chance, and while the library literature might not include a wealth of information on how to teach successful browsing, the art historical literature is rife with examples of artists using chance as part of their artistic practice. Dadaists like Hans/Jean Arp and Marcel Duchamp relied on chance to create their respective works Squares arranged according to the laws of chance (1916-17) and Three standard stoppages (1913-1914). The surrealists appropriated the phrase “as beautiful as the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table” from the book Les chants de Maldoror (1869) by Isidore-Lucien Ducasse, also known by the pen name the Comte de Lautréamont, to describe the power chance had for surrealism.

Later artists and art movements have continued to explore chance as artistic practice. An anthology of chance (1963) edited by La Monte Young was instrumental in the development of Fluxus, where artists like John Cage and Dick Higgins used chance to create musical scores. Ellsworth Kelly's series Spectrum colors arranged by chance and Gerhard Ricter's 4900 colours serve as further examples. Could the artistic practice of chance be used to create moments of serendipitous discovery through browsing and demonstrate to students the library's role in creative exploration?

Nina Katchadourian

The answer to this question lay in the artwork of Nina Katchadourian. Since 1993, Katchadourian has been going into libraries and creating book spine poems by “sorting through a collection of books, pulling particular titles, and eventually grouping the books into clusters so that the titles can be read in sequence.”Footnote 4 The resulting poems are then photographed. By mimicking Katachadorian's process, students would have the opportunity to browse the stacks, experience serendipitous discovery, and create an art object using library resources.

The lesson plan

The original lesson plan was intended for a 55-minute class period. First, the book spine poetry activity is explained and Nina Katchadourian's Sorted books project is introduced through a short PowerPoint presentation. Then, students go into the stacks and create their own book spine poems. After making their poems, students set them up for display. Finally, students get the chance to walk around, read and discuss their classmates’ poems. Once the class was over, poems remained on display in the library for the remainder of the semester.

The learning outcomes are as follows. At the end of this lesson, students will: engage in the library as a place for artistic inspiration and creative exploration, experience browsing the stacks for serendipitous discovery and create their own art object in the form of a book spine poem.

The first iteration

The lesson was first implemented in Art UNV 101, a first-year experience course for students enrolled in the Department of Art. This class was chosen for a couple of reasons. First, because of the instructor's reputation for welcoming experimentation. Second, because of the professor's already existing relationship to the library. Browsing the library for inspiration is a key part of the professor's art practice now and during their education. In the end, the lesson plan was a success. Students were engaged and clearly enjoying the class. Many wrote more than one poem.

In fact, the lesson was successful in ways not originally intended. Library patrons interpreted the book spine poetry exhibition students created as interactive and began creating new poems with the books in the exhibition. Thus, patrons also had the chance to experience serendipity and the library as a place of creative exploration.

The second iteration

Given the success of the first iteration, the lesson was expanded to an Advanced Drawing class the following semester. Since Advanced Drawing is a studio class, class periods are one hour and 50 minutes, instead of 55. This allowed for a more robust lesson plan. The beginning portion of the class, outlined above, remained the same. Then, once students had created their book spine poems, they chose either their poem or one of their classmates and sketched a response to it for the remaining 45 minutes of class. They also had the opportunity to complete a finished drawing based on their chosen poem for extra credit.

The third iteration

The following year, the lesson was expanded even further in another Advanced Drawing course. This time, instead of offering students extra credit for a finished drawing, the finished drawing would serve as students first graded assignment. Once drawings were complete, the class critique was held in the library with the librarian as an active participant. Drawings were then displayed alongside students’ book spine poems in the library's display area for the remainder of the semester. Labels were also created this time, listing students’ names, artwork titles and indicating which poem had inspired the drawing.

Labels were intended to not only give students credit for their work but also to discourage viewers from interacting with the exhibit and making new poems. Although the spontaneous book spine poems patrons created in previous semesters was a welcome, serendipitous, addition, letting patrons rearrange the poems would have complicated the continuity needed to link the poems and their drawings. As it turned out, these labels were not enough. After a few weeks additional signage was created, asking patrons, specifically, not to move the books. The books were also marked as unavailable in the catalog so they wouldn't circulate during the exhibition.

Outcomes of the third iteration

There were several surprising outcomes and consequences to using book spine poems as prompts for finished drawings. Most students chose to use a poem created by someone other than themselves, and no students voiced any complaints about having to use a poem as inspiration. Instead, students enjoyed the process of reviewing the array of poems and contemplating a variety of interpretations that could yield successful and interesting drawings. And, most impactfully, the poems enabled students to focus on expressive content over conventional technique. Once they found this expressive framework, many students continued to use it as the basis for their artworks for the remainder of the course and, in some cases, until graduation.

The poems themselves touched on an array of different traditional artistic criteria; there were poems that were expressive, abstract, avant-garde, formal, instrumental and realistic. Consequently, students’ drawings were also quite diverse in their approach and aesthetic. In comparison to previous classes, students were more willing to venture beyond their conventional comfort zones and experiment. The word-based nature of the poems encouraged students to think creatively and critically about how they would interpret the content. There was no previous style or visual solution directing their aesthetic conclusions, as would be the case if visual artifacts were used as prompts.

Students could also select from a broad and unexpected set of potential subjects and ideas for exploration. This allowed them to find content that was relevant to their experience but not the kind of content they would have otherwise thought to use as inspiration for their artwork. While the variety of poems gave students a wide selection, that selection was also limited, providing students the opportunity to choose something that excited them without overwhelming them with too much choice.

This project naturally led students to a content-first approach to their drawings. Through developmental sketches, students could easily iterate a multitude of ways to express the content of the poem. Intent, content and expression drove the consideration of media, composition, subject and method. This placed students’ formal and technical skills in service to their expressive interest. Students naturally used what they learned in their foundational drawing courses to express their interpretation of the poem.

Likewise, the critique of the drawings naturally used the poem as a framework for discussions, so the critique utilized content as a driver of formal and technical proficiencies. This was a significant advancement from the critique experience in introductory drawing courses where students often discuss outcomes from a technical framework first. Additionally, other students in the class often expressed the approach they had in mind for the interpretation of a particular poem. Thus, the project induced a degree of creative lateral thinking.

Finally, students at this level, when given an open-ended opportunity to create art without guidance, will typically fall into one of two patterns: one being the “I don't know what to make work about” response and the other being the tendency to continue to make work that focuses on technical proficiency without venturing into any personal voice or expression. The poems encouraged students to utilize research and exploration early in their process so they could examine the subjects and ideas, not just the technique and form, that would inspire not only this specific drawing but future artworks.

Student work examples

What follows are some examples of student work, including the student's chosen poem, a description of their drawing and a summary of how the assignment influenced the students’ artwork.

Student One, a third-year Studio Art and Fashion double major:

Art as existence

Make it fabulous

This student had previously made some technically capable drawings that were very conventional. For this project they chose to combine their interest in fashion and self-portraiture with concerns they had about how young girls’ body expectations are conditioned in childhood by books and toys. The poem gave them permission to explore less orthodox modes of expression. Their drawing was a self-portrait rendition of a paper dress up doll and its accessories. Throughout the rest of the semester, the student continued to explore the theme of children's toys for girls and the print materials that had shaped their self-image. Their final drawing for the course was a life-sized dress-up doll of themselves, complete with a variety of outfits and accessories. The viewer was invited to dress the doll as they chose. The poem did not cause a major shift in the content the student chose to explore, rather it gave them the confidence to consider less conventional strategies for expressing their thoughts and feelings about their childhood experiences. The simple phrase, “Make it fabulous” became a refrain for them over the course of the semester and inspired them to think more grandly about their work.

Fig. 1. Student one, book spine poem, “Art as Existence, Make it Fabulous.”

Student Two, a third-year Studio Art major:

Controversies

Dialog

Buildings must die

Ruins of ancient Rome

Stillness & light

This student's drawing was a landscape. Large rocks dominated the pictureplane and, on one of the rocks in the foreground, sat a single frog looking to the horizon. The drawing was done in graphite and had an intentional coolness to it that lacked any expressive mark-making. The student had already started working in landscape prior to this drawing but their landscapes were typically pastoral, focusing on the depiction of pleasant views. With this drawing they began to see the landscape as a means for expressing concerns about nature and how we live within it. The poem made them reconsider what they could express through their subject and served as a tool for moving them beyond the more obvious and acceptably conditioned tendencies a student would typically gravitate toward. The student went on to build their entire body of work for the semester from this one drawing, and those drawings later served as the basis for their thesis exhibition the following year. The thread of destruction, ruin and stillness found in this drawing became the core content of their future work.

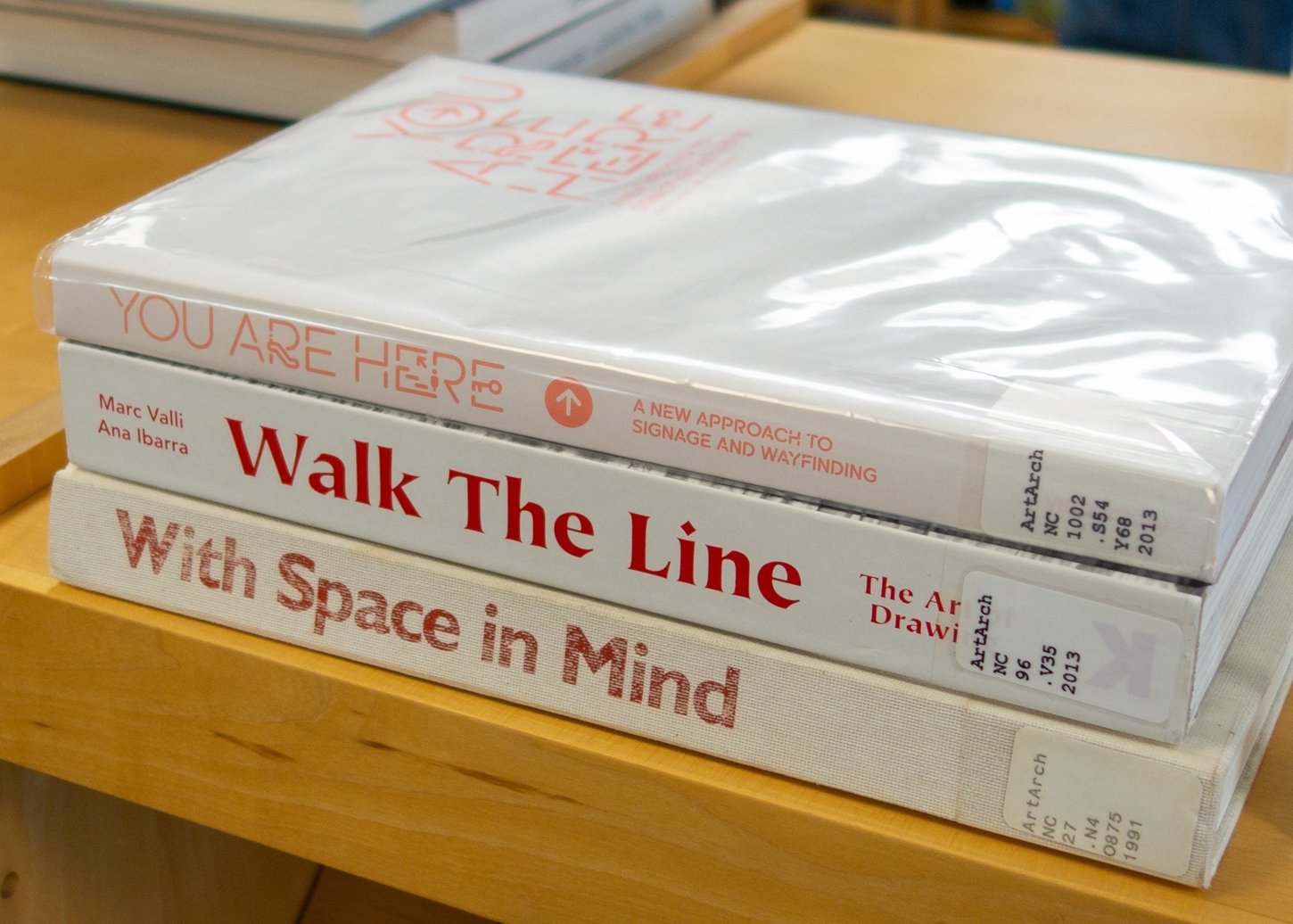

Fig. 2. Student three, book spine poem, “You are here, Walk the like, With space in mind.”

Student three, a third-year Studio Art major:

You are here

Walk the line

With space in mind

Like many students at this level, this student's energies to this point had largely focused on the development of conventional drawing techniques. They came to the class with a strong set of skills in representational drawing and composition. However, their ability to express personal content was not as well developed as their technical ability to make a drawing. The student embraced the text “Walk the line, With space in mind,” seeing the lines as emblematic of their relationship with their partner. The student stated that they were always attentive to possible household hazards but their partner was not. This created a level of tension when they were in a shared space. The drawing portrayed the student sitting on a sofa with a glass of water balancing precariously close to the edge of a table. With this drawing, the student began to explore ways to build tension and the time it takes for the viewer to recognize this tension. As with the two previous samples, the poem gave the student permission to explore their own voice and take notice of the issues they wished to express through their art. Their entire body of drawings for the semester explored variations of everyday household threats they were aware of but their partner was oblivious to.

Conclusion

Given the lesson plan's success, the third iteration will continue to be used in Advanced Drawing courses. In addition, a related activity has been added to library tours where students are challenged to find the most interesting, absurd, or humorous title on the shelves and present it to the class. The winner is then chosen by popular vote. There are also plans for additional exhibitions that will encourage library patrons to engage with the stacks through the artistic principle of chance with instruction pieces like those found in Fluxus artist Yoko Ono's Grapefruit (1963).

In addition, the lesson plan has revealed an important gap in the art librarian literature. While artists’ preference for browsing over searching as an information seeking strategy is well known, there is a lack of literature detailing practical ways that browsing and the serendipitous discovery that makes browsing so appealing can be fostered in the art library, especially as part of library instruction. While the artistic principle of chance has proven to be an effective entry point in this example, there is a lot more ground for future art librarians to explore.