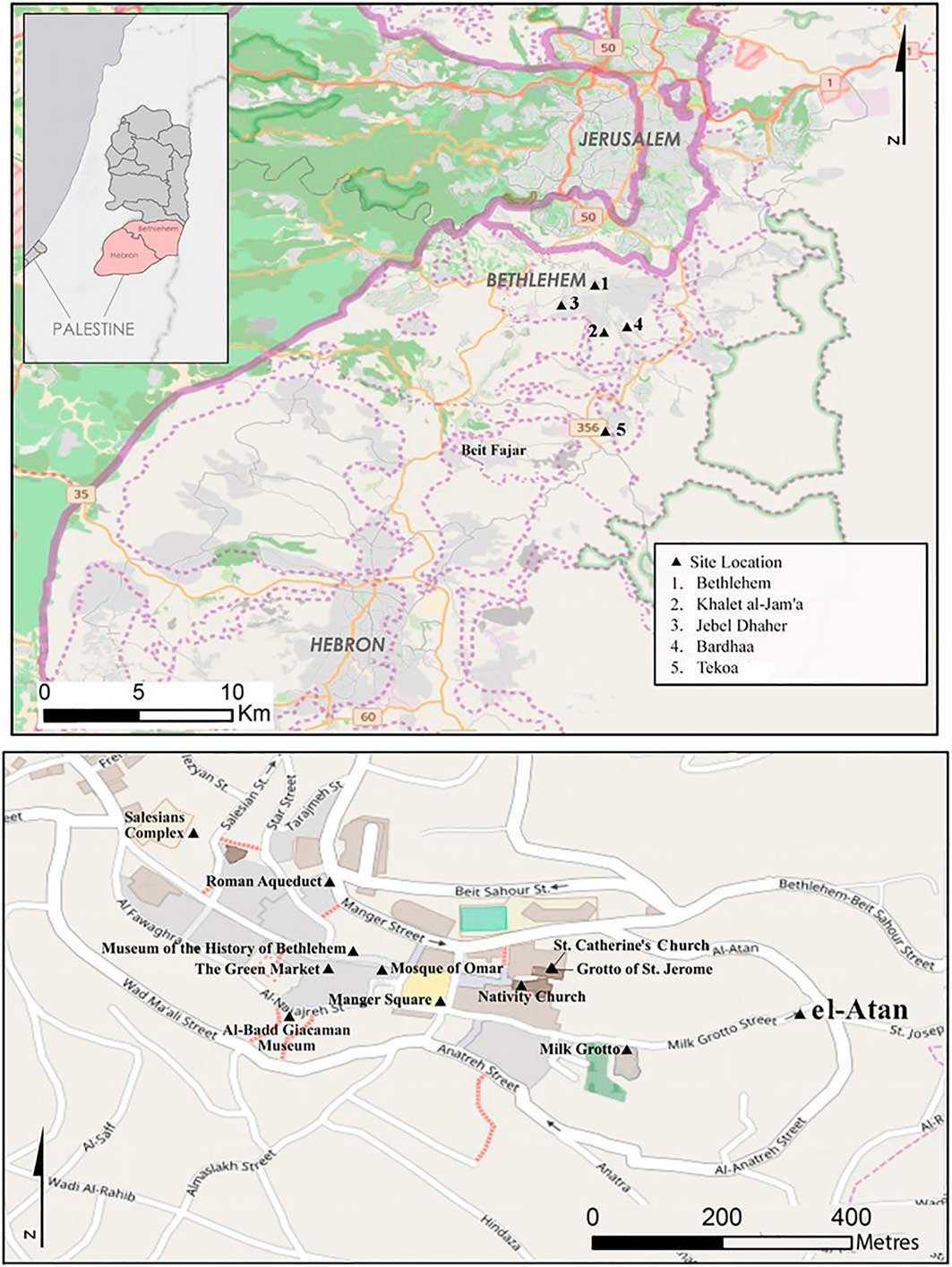

A survey of the city of Bethlehem and its surroundings, implemented as part of the 2015–2016 Sapienza-Palestinian MOTA-DACH Expedition archaeological investigations, has identified and documented archaeological, historical and cultural sites and monuments dating from the Early Bronze Age to the Islamic Period (fourth millennium BC to second millennium AD) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Top) map of the area of Bethlehem with necropolis locations; bottom) city centre with el-Atan tomb location.

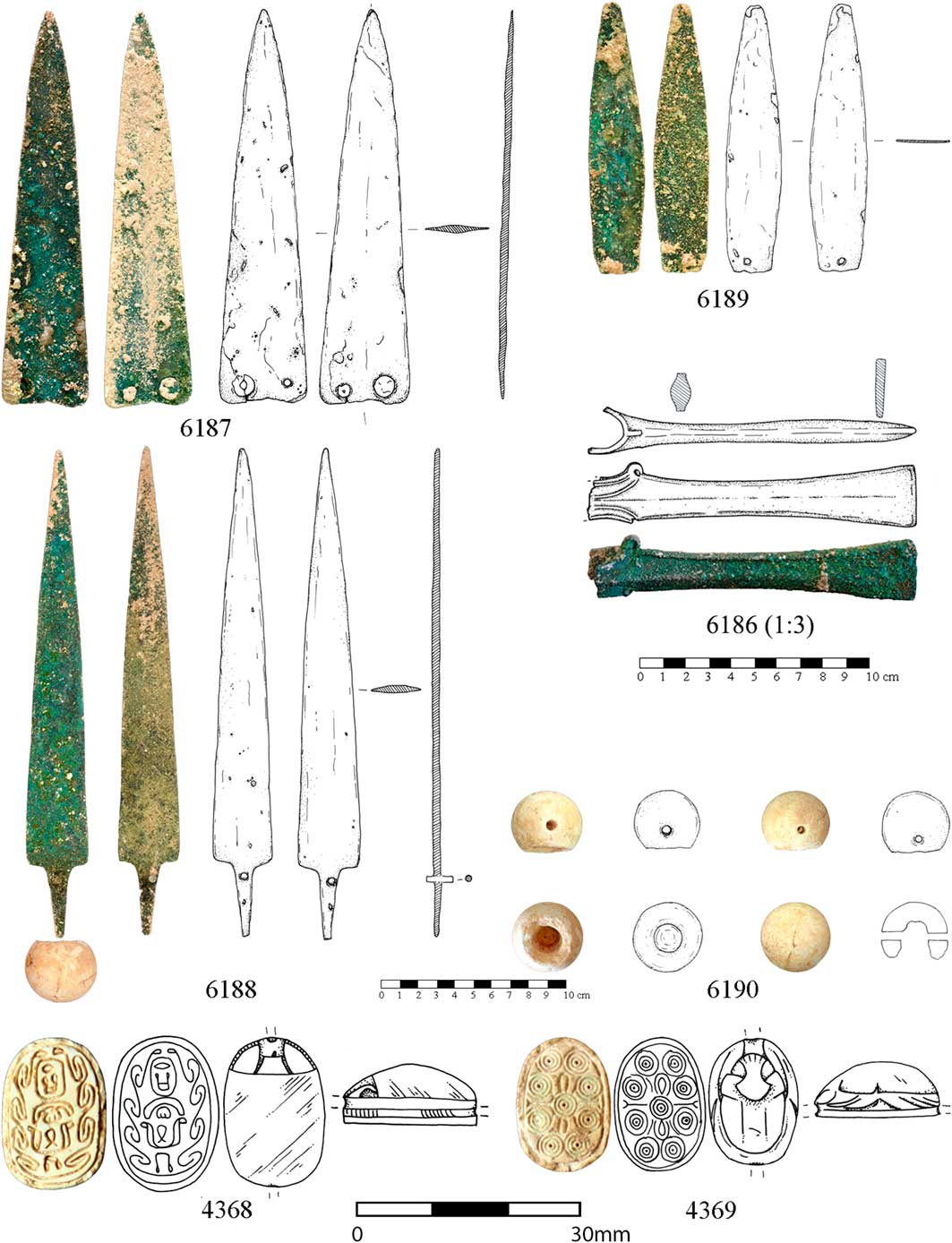

Four different necropolises—Khalet al-Jam’a, Jebel Dhaher, Bardhaa and el-Atan—are located on the terraced slopes of the limestone hill of Bethlehem, within a 1.5km radius of the Church of the Nativity, and were the subject of rescue excavations in 2015 and 2016 (Nigro et al. Reference Nigro, Montanari, Ghayyada and Yasine2015, Reference Nigro, Montanari, Ghayyada and Yasine2017a & Reference Nigro, Montanari, Guari, Tamburrini, Izzo, Ghayyada, Titi and Yasineb). Although affected by destruction and looting prior to the MOTA-DACH rescue excavation, the Khalet al-Jam’a necropolis (Figure 2) originally contained at least 100 shaft tombs, which were used during the EB IV (2300–2000 BC) to MB I–III (2000–1500 BC) periods, and up to the Iron Age IB–II (1050–700 BC). Khalet al-Jam’a long use-life and its huge number of tombs and their assemblages (Figure 3) suggest that it was the main necropolis serving the pre-Classical town of Bethlehem from the Middle Bronze Age to the Iron Age (Nigro Reference Nigro2015).

Figure 2 Khalet al-Jam’a tomb 9 during rescue excavation in 2015, looking south.

Figure 3 Weapons and scarabs from Khalet al-Jam’a tomb A2.

The Jebel Dhaher necropolis (Figure 4) was discovered in 2016 to the south-west of Bethlehem during construction works. It also contained shaft-tombs with round shafts and usually a single, circular, domed chamber. Associated artefacts date the tombs to the EB IVB (2200–2000 BC) to the Middle Bronze Age, with re-use during the Early Iron Age. The Jebel Dhaher and Khalet al-Jam’a necropolises were therefore contemporaneous.

Figure 4 Map of four tombs in the Jebel Dhaher cemetery (2016).

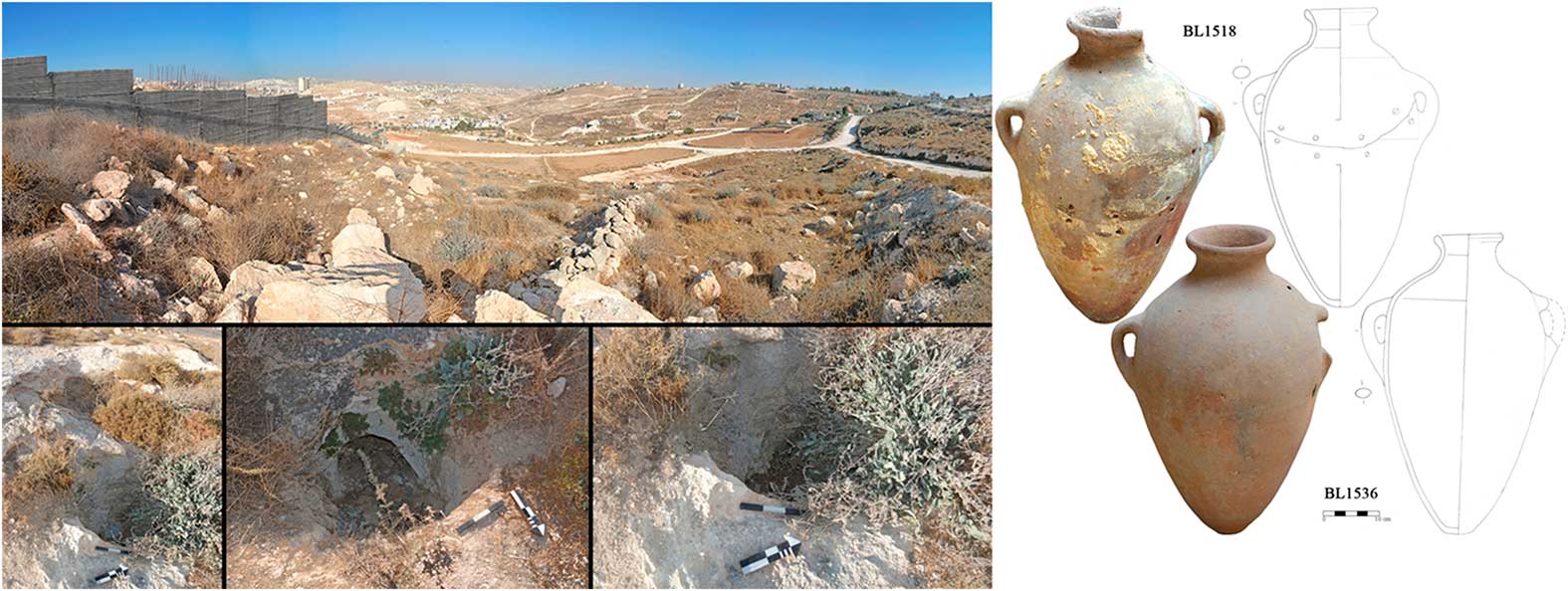

To the east of Khalet al-Jam’a lies a necropolis (Bardhaa) in the village of Bardhaa (Figure 5), which was looted between 1967 and 1995. MOTA-DACH estimates that there were originally around 50 tombs. Excavations at Bardhaa revealed that the tombs are mostly of the shaft-single chambered type, with squared or round shafts. Bardhaa began use in the EB IV period and flourished in the Middle Bronze Age. As with Khalet al-Jam’a and Jebel Dhaher, the Bardhaa necropolis belongs to a system of cemeteries first established in the Early Bronze Age, between Wadiat ‘Artas, Wadi Ta’amireh and Wadi et-Tin to the south of Bethlehem up to Tekoa. The necropolises were possibly connected to local late third-millennium BC sister tribes.

Figure 5 Bardhaa necropolis: panoramic view from the north and details of three shafts (left); two Middle Bronze Age jars (right).

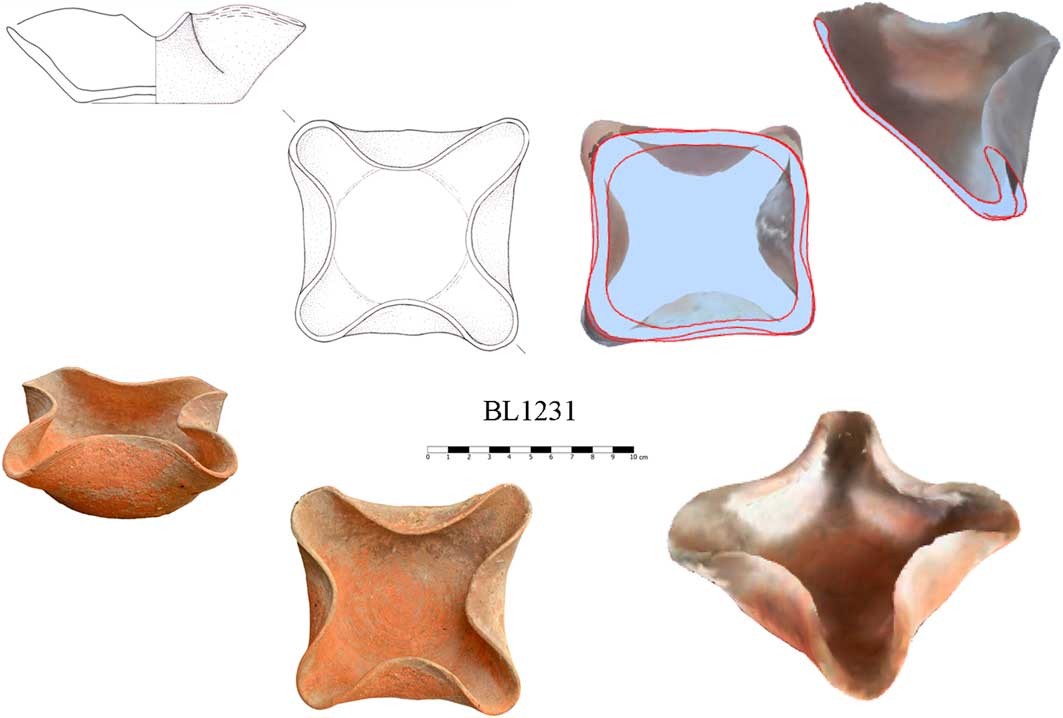

An EB IVB tomb (el-Atan) was discovered accidentally in 2009 close to the Milk Grotto, in el-Atan Street, Bethlehem. This shaft single-chamber tomb was part of the Early Bronze Age to Byzantine-period cemetery extending to the east and south of the Church of the Nativity (Prag Reference Prag2000: 177). In 2016, the MOTA-DACH, with the help of Sapienza, examined human remains and a composite ceramic assemblage dating to the EB IVB from that tomb (Figure 6).

Figure 6 An EB IVB four-spouted lamp from el-Atan Tomb, with 3D sections and rendering (right).

The newly discovered Early and Middle Bronze Age cemeteries of Khalet al-Jam’a, Jebel Dhaher, Bardhaa and el-Atan illuminate the history of Bethlehem in the third and second millennia BC. The lack of pre-Classical documentary evidence (a disputed mention in the el-Amarna Letters is no longer considered reliable) forces a reliance on archaeological data as a means to understand settlement and occupation patterns. Cemetery clustering from the Early Bronze Age onwards suggests that, as with Jerusalem, Bethlehem gradually developed into a fortified town, culminating in the Middle Bronze Age with the rise of a city. The EB IV necropolises, which were used throughout the Middle and Late Bronze Ages, and, in the cases of Khalet al-Jam’a and Jebel Dhaher, into the Iron Age, provide strong evidence for progressive sedentism and the rise of a city that controlled trade and transhumance by nomadic and semi-nomadic tribes living in the wadis west of the Dead Sea.

Acknowledgements

Work at Bethlehem is carried out in cooperation with the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities of Palestine. Our deepest thanks go to Rula Maa‛yaa and Saleh Tawafsha. Special thanks are given to the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, the DGSP—Ufficio VI Settore Archeologia and the Italian Consulate in Jerusalem. Our thanks also go to the Academic Authorities of Sapienza University of Rome, E. Gaudio, Stefano Asperti, Teodoro Valente, Bruno Botta, Alessandra Brezzi and Claudio Lombardi for their academic and technical support, and to all these institutions that made the present study possible. All figures are copyright of the Sapienza University of Rome Expedition to Palestine and Jordan.