Introduction

Desert kites are well-known archaeological features in the Middle East. Distributed over large geographic areas, they were probably not constructed simultaneously or as part of a continuous process (Crassard et al. Reference Crassard, Barge, Bichot, Brochier, Chahoud, Chambrade, Chataigner, Madi, Régagnon, Seba and Vila2015). Here we announce two such newly discovered sites (Keimoes 1 & 2), located 22km north of Keimoes in the Northern Cape Province of South Africa (Figure 1) in the arid, landlocked Nama-Karoo Biome. The two sites are separated by a non-perennial stream, in an open, relatively flat landscape. Keimoes 1 is farther to the west and slightly higher than Keimoes 2 (Figure 1). Both sites were constructed upon a hard calcrete deposit with pockets of red aeolian Kalahari sand.

Figure 1. Map of South Africa showing Keimoes 1 and 2 (drawing: Wendy Voorvelt).

Brief description of the kite-like structures

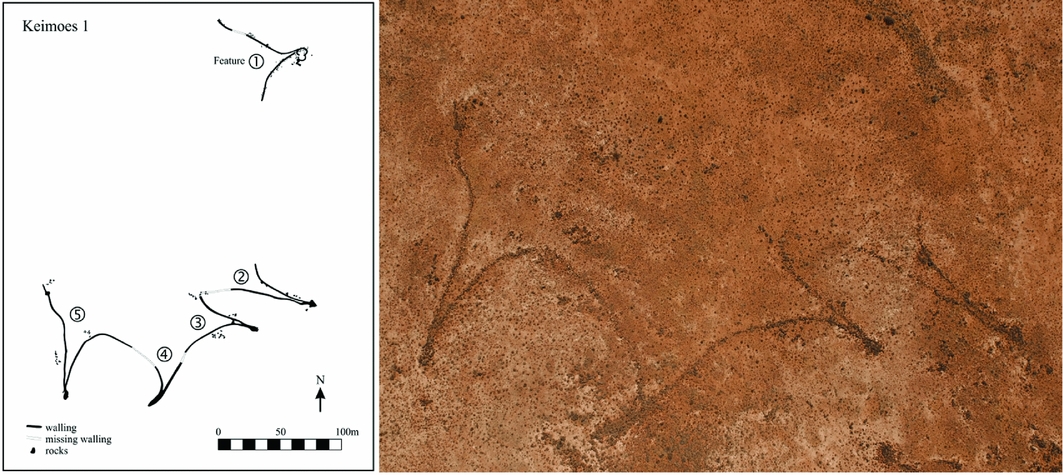

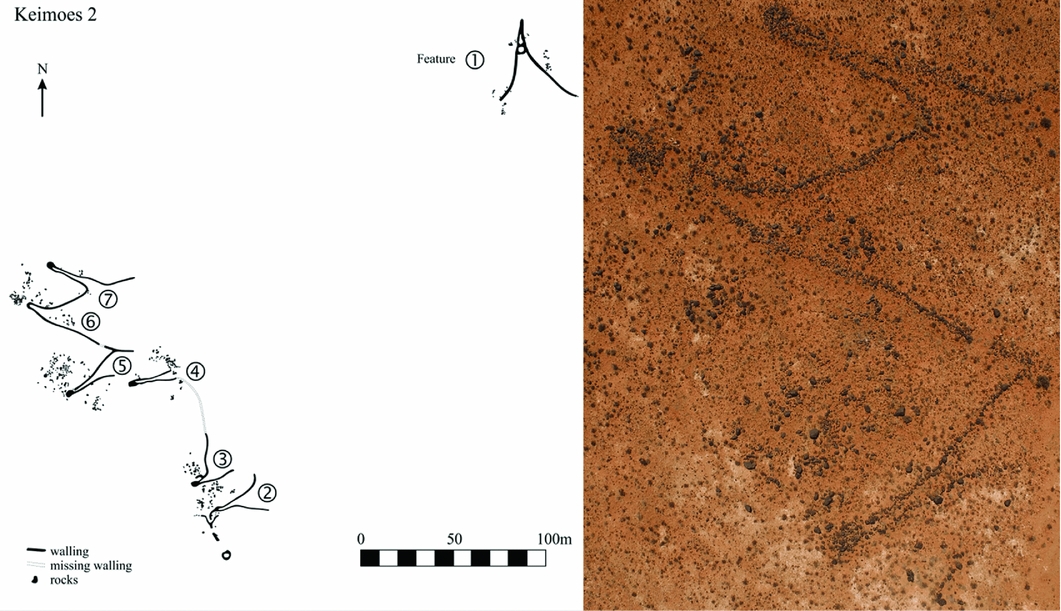

Keimoes 1 is the smaller of the two sites, with five funnel-shaped features. The first funnel is an isolated structure with two arms converging on an enclosure. This is located 156m north of four similar structures, which join to form a single funnel chain (Figure 2). This layout repeats itself at Keimoes 2, where an isolated structure is located 243m to the north-east of six funnel-shaped structures (Figure 3). The length of the funnel arms at both sites varies, with the longest being ~75m, and the shortest ~38m. The arms converge into funnel tubes ~1.2m in width and 6–11m in length, before apexing into relatively small enclosures ~2m in diameter.

Figure 2. Site plan of Keimoes 1 on the left with aerial image of funnels 2–5 on the right (drawing: Wendy Voorvelt).

Figure 3. Site plan of Keimoes 2 on the left with aerial image of funnels 5–7 on the right (drawing: Wendy Voorvelt).

All the kites were constructed, or rather shaped, by organising local dolerite boulders into funnel-shaped features. This method differs slightly according to the location and distance from the final convergence points/apex enclosures. The guiding arms—those most distant from the apex enclosures—comprise alignments of single, large and roughly packed stones, sometimes incorporating in-situ dolerite outcrops/boulders. The arm extremities have no visible vertical organisation, and are ~0.2–0.3m high (Figure 4). The walls become slightly higher closer to the apex enclosures, are more deliberately constructed and, in some instances, show vertical stacking. Funnel 3 at Keimoes 1, and funnel 1 at Keimoes 2, stone-built cells/corrals (~4m in diameter), are situated inside the kites and attached to both guiding arms before entering the funnel tube (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Ground-level photograph of low stone walls (photograph: Jaco van der Walt).

Figure 5. Plan drawing showing stone-built cells of funnel 3 at Keimoes 1 and funnel 1 at Keimoes 2 (drawing: Wendy Voorvelt).

The Keimoes kite-like structures share characteristics with examples from the Negev (Israel) and Sinai (Egypt) Deserts (Figure 6), including general layout and isolated funnel-shaped structures. They are smaller than the larger, continuous chain-like arrangements characteristic of Middle Eastern and Central Asian kites (Echallier & Braemer Reference Echallier and Braemer1995).

Figure 6. Har Shahmon desert kite on the left (redrawn: Wendy Voorvelt, after Holzer et al. Reference Holzer, Avner, Porat and Horwitz2010), compared to funnel 1 at Keimoes 1.

Current interpretation

In the absence of dates and cultural material, we can only hypothesise about who built these structures. There is no reason to assume that the kites were constructed by early European settlers. Stone-built structures pre-dating the arrival of Europeans are common in Southern Africa—mostly associated with Iron Age farming communities that settled in South Africa from ~1700 years ago (e.g. Huffman Reference Huffman2007). Remains of such settlements are widely distributed in areas with viable arable land and pastures for grazing. No funnel-shaped structures have been reported in association with Iron Age sites.

Stone walling associated with a Ceramic Later Stone Age techno-complex (see Lombard et al. Reference Lombard, Wadley, Deacon, Wurz, Parsons, Mohapi, Swart and Mitchell2012) is found at Simon se Klip along the west coast of the Western Cape. From the Seacow River Valley of the Northern Cape Province, Later Stone Age (eleventh century AD) circular, stone-walled stock enclosures are known (Sampson Reference Sampson2010). Stone-built structures associated with the Holocene Later Stone Age (last 12000 years) are rarer and mostly consist of stone circles (e.g. Kinahan Reference Kinahan1991; Parsons Reference Parsons2004; Sampson Reference Sampson2010; Sadr Reference Sadr2012; Veldman et al. Reference Veldman, Parsons and Lombard2017). The only funnel-shaped structure that we are aware of is at Graafwater, 95km to the south-west of the Keimoes kites (Beaumont et al. Reference Beaumont, Smith, Vogel and Smith1995). There is no record of southern African stone structures pre-dating the Holocene Later Stone Age.

Discussion and conclusion

Thus far, it is unreasonable to assume that the Keimoes kites were built and/or used by European settlers or Iron Age farming communities, or that they pre-date the Holocene. Based on the widely accepted function for kites as being hunting traps (Holzer et al. Reference Holzer, Avner, Porat and Horwitz2010), and the ethno-historical records of various kinds of hunting traps used by San hunter-gatherers, the parsimonious interpretation would be that they were associated with hunter-gatherer groups. For the last two millennia, however, this landscape was also occupied by Stone Age herding communities (who also hunted); they cannot be discounted as users of these features.

The known distribution and number of recorded kites has increased greatly across the Near East, Arabia, the Caucasus and Central Asia (Barge et al. Reference Barge, Brochier and Crassard2015). The Global Kites project (http://www.globalkites.fr/) was developed to consider kites as a wide-ranging phenomenon, focusing mainly on the Middle East and Central Asia (Crassard et al. Reference Crassard, Barge, Bichot, Brochier, Chahoud, Chambrade, Chataigner, Madi, Régagnon, Seba and Vila2015). By September 2016, 5210 kite structures had been recorded in the northern hemisphere. Here, we add to this inventory of kite-like structures from a desert-like biome in Southern Africa. These features support notions that they played an important role in animal exploitation in the context of many diverse Old World societies, even though we do not yet understand their exact socio-economic context.

Acknowledgements

Our research is funded by an African Origins Platform Grant (98815), awarded by the National Research Foundation of South Africa. We thank two reviewers for their input to this text, Simon Todd, for alerting us to these features, and Willem Snyman, who provided access to the sites.