Frontispiece 1. Waste pit with misfired pottery vessels, under excavation during 2020 in the Altona district of Hamburg, Germany. The excavations, in advance of development of the site, have revealed two pits attesting to ceramic production during the first half of the eighteenth century. Products included lead-glazed tablewares, three-legged kettles, or ‘Grapen’, for cooking on an open hearth, and black-glazed stove tiles. Documentary records and the results of earlier excavations at the site indicate that, some time before 1770, production switched to an elaborate range of faience objects, including stove tiles, vases and chandeliers. By 1803, however, production at the site had ceased due to competition from other tablewares, including porcelain and English earthenware. Photograph © Maren Kaube, Arcontor Projekt GmbH.

Frontispiece 2. An archaeologist working on a submerged logboat in Lake Constance (Bodensee) in spring 2021. The 8.56m-long watercraft was first discovered in 2018. Subsequent work has found no associated features, such as pile dwellings, in the vicinity of the logboat, which lies in the Seerhein immediately south of Konstanz. The boat is made from the dugout trunk of a lime tree, with an inserted stern board of oak (the bow is missing). It dates to the twenty-fourth to twenty-third centuries BC. After in situ work to stabilise the wood, the boat will be raised and transferred to the conservation laboratory of the Baden-Württemberg State Office for the Preservation of Monuments (photograph © LAD im RPS, Florian Huber/submaris).

Long COVID

![]() In the novel Cold earth a group of archaeologists on fieldwork in a remote part of Greenland find themselves isolated after a global pandemic severs communications with the wider world.Footnote 1 At first, the lack of news allows the team to focus on their excavation of a Norse settlement. Soon, however, the uncertainty about what might or might not be happening to family and friends back home leads the group's members to confront their own pasts—and one another. Published back in 2009, a decade on, the novel assumes an eerie resonance in the era of COVID-19. In the real world, the current pandemic may have caught a small number of archaeologists in isolated locations, but for most of us—as for the wider population—the experience of a global virus outbreak has been the exact opposite of that of the novel's protagonists: we have been socially and physically isolated at home with an excess of news flooding in from all around the world. Nonetheless, where the novel and reality align is in the impact of these different forms of isolation and uncertainty on the mind and mental health.

In the novel Cold earth a group of archaeologists on fieldwork in a remote part of Greenland find themselves isolated after a global pandemic severs communications with the wider world.Footnote 1 At first, the lack of news allows the team to focus on their excavation of a Norse settlement. Soon, however, the uncertainty about what might or might not be happening to family and friends back home leads the group's members to confront their own pasts—and one another. Published back in 2009, a decade on, the novel assumes an eerie resonance in the era of COVID-19. In the real world, the current pandemic may have caught a small number of archaeologists in isolated locations, but for most of us—as for the wider population—the experience of a global virus outbreak has been the exact opposite of that of the novel's protagonists: we have been socially and physically isolated at home with an excess of news flooding in from all around the world. Nonetheless, where the novel and reality align is in the impact of these different forms of isolation and uncertainty on the mind and mental health.

Not so long ago, archaeological fieldwork was often characterised by an extended lack of communication with home; in the late 1990s, I worked for a month in the Fezzan of southern Libya without so much as a call or postcard to family or friends. In the absence of mobile phones and social media, such ‘social distancing’ was sometimes unavoidable, but often intentional—a deliberate separation of home and away, whether in pale imitation of fabled archaeological expeditions or simply to escape in both time and space from our usual routines. In more recent years, such isolation seems unthinkable and Cold earth exploits our heightened dependence on communication, and the consequences of disconnecting—or being disconnected.

A new report published by the British Academy picks up on some of the issues, including social isolation, precipitated or intensified by the pandemic. The COVID decade: understanding the long-term societal impacts of COVID-19 identifies a series of psychological, social, cultural, economic and political consequences of the spread of the virus that will define the decade to come.Footnote 2 Many of these issues are familiar from pre-pandemic times: mental health, loneliness and the need for better skills and training, social care and community cohesion. If the problems are familiar, however, governmental and societal responses will need to be innovative and creative in the face of recession and restricted national budgets.

The areas of long-term societal impact identified in the British Academy report include widening geographic and structural inequalities; worsened physical and mental health; rising unemployment and economic recession. A companion British Academy report takes these impacts and identifies high-level strategic policy goals through which we might “build back better”.Footnote 3 These include reimagining urban spaces, strengthening community-led social infrastructure and promoting a shared social purpose. Where might archaeology fit into this picture—not only in relation to the impact of the pandemic's consequences on what we currently do, but also in terms of how we might contribute new and creative solutions to help address some of these societal goals?

The rapid and successful development of vaccines has rightly underscored the centrality of the sciences and medicine in the global effort to combat COVID. Alongside these STEM subjects, however, there is a renewed and important role for so-called SHAPE research—social science, humanities and the arts for people and the economy—including archaeology, in responding to the challenges ahead. This might involve directly relevant or applied research, drawing, for example, on the evidence for earlier pandemics to provide comparative insights into social or health consequences, or helping to understand the cultural reasons for ‘vaccine hesitancy’. It might also involve some deeper rethinking of the value and purpose of subjects such as archaeology. Scholars often devote much time and effort to reflecting on core disciplinary values and on the intersections with other subject areas and wider societal agendas. Archaeology is no exception and can point to a long history of public engagement, community archaeology and activism. Over the past two decades, in particular, the amount and breadth of archaeological work directed towards contemporary societal issues has notably increased, addressing, for example, homelessness, racism, the legacies of colonialism and the climate emergency. Does COVID-19 present an unprecedented moment for archaeology to build on such work, and to reflect more deeply on the discipline's purpose and to reset its course? The June 2020 editorial featured contributions penned by colleagues around the world during the early months of the pandemic, offering their initial thoughts on the impact of COVID-19 on archaeology and how the subject might respond and adapt. Looking back 12 months on, it is striking how quickly the consequences and solutions were identified—the deepening of inequalities and a need for better communication of the value and relevance of archaeology, for example. Perhaps, in reality, we already had the diagnosis; what was missing was the crisis through which change might be brought about. How then might archaeology grasp the ‘opportunity’?

Archaeological therapy

![]() One area of particular relevance is recent research into archaeology as a form of rehabilitation or therapy. Several projects have explored the potential of archaeology and the historic environment more broadly in relation to issues of wellbeing. For example, the Continuing Bonds project uses archaeological case studies as the basis for workshops with end-of-life care professionals to explore contemporary attitudes to death and to facilitate discussion with patients and families around dying and bereavement.Footnote 4 Meanwhile, a number of museums and heritage sites, such as the Beamish Living Museum of the North, located in northern England, have developed dementia-friendly programmes, using their collections to enable people living with the condition to visit with confidence and to improve physical and mental health. Some other projects have sought to use archaeological fieldwork as a form of therapy. Perhaps one of the best-known examples involves several groups working with military veterans and serving personnel who are recovering from traumatic experiences or learning to adapt to life-changing physical injuries. In an article published in our February 2020 issue, for example, Everill et al. reported on Operation Nightingale, an initiative that provides former and current service men and women with the opportunity to participate in archaeological fieldwork intended to develop skills and to promote self-esteem and confidence.Footnote 5

One area of particular relevance is recent research into archaeology as a form of rehabilitation or therapy. Several projects have explored the potential of archaeology and the historic environment more broadly in relation to issues of wellbeing. For example, the Continuing Bonds project uses archaeological case studies as the basis for workshops with end-of-life care professionals to explore contemporary attitudes to death and to facilitate discussion with patients and families around dying and bereavement.Footnote 4 Meanwhile, a number of museums and heritage sites, such as the Beamish Living Museum of the North, located in northern England, have developed dementia-friendly programmes, using their collections to enable people living with the condition to visit with confidence and to improve physical and mental health. Some other projects have sought to use archaeological fieldwork as a form of therapy. Perhaps one of the best-known examples involves several groups working with military veterans and serving personnel who are recovering from traumatic experiences or learning to adapt to life-changing physical injuries. In an article published in our February 2020 issue, for example, Everill et al. reported on Operation Nightingale, an initiative that provides former and current service men and women with the opportunity to participate in archaeological fieldwork intended to develop skills and to promote self-esteem and confidence.Footnote 5

All of these projects have grown from different backgrounds and in response to different needs. Some aim to add to our knowledge about the past through public participation in fieldwork, others have broader social aims, using archaeological objects or historic environments to address wider societal issues. All, however, can be linked by the concept of archaeology as therapy. In turn, these initiatives intersect with a wider movement known as ‘social prescribing’, an approach that allows doctors and other healthcare professionals to refer patients for a variety of non-clinical support. Prescribed activities might include cold-water swimming for people with mild depression, community gardening to tackle loneliness, volunteering to enhance self-esteem and group exercise to build fitness. Such activities are intended as preventative or early and complementary intervention to improve wellbeing and to relieve pressure on primary healthcare services. Typically, these activities are provided by so-called ‘third-sector’ organisations—a diverse mix of community groups, social enterprises and charities—working alongside conventional health services.

A good example of a recent therapeutic archaeology initiative under the banner of social prescribing is the Human Henge project, which uses the landscapes around Stonehenge and Avebury as the basis for creative or performative events—music, writing, art and so on—to enhance the wellbeing of local people with various mental health problems.Footnote 6 The project emerges from the wider framework of landscape archaeology and approaches such as phenomenology, which emphasise sensory and emotional experience of the landscape, as well as work on the meaning of place and the role of the imagination in creative encounters with the past. It also connects the therapeutic value of monuments and landscapes in the present with their potentially similar functions and meanings in the past, evoking a broad continuity in the healing power of ancient places.Footnote 7

The concept of social prescribing was advancing rapidly pre-COVID. The role of governments and political organisations in promoting the wellbeing of citizens is already embedded in a number of international programmes, such as the UN's 17 Sustainable Development Goals.Footnote 8 In turn, national governments and state organisations have increasingly looked to embed wellbeing in their policies and mission statements. The pandemic, with its intensification of society's many and diverse problems around wellbeing, seems likely to intensify interest and research into this approach.

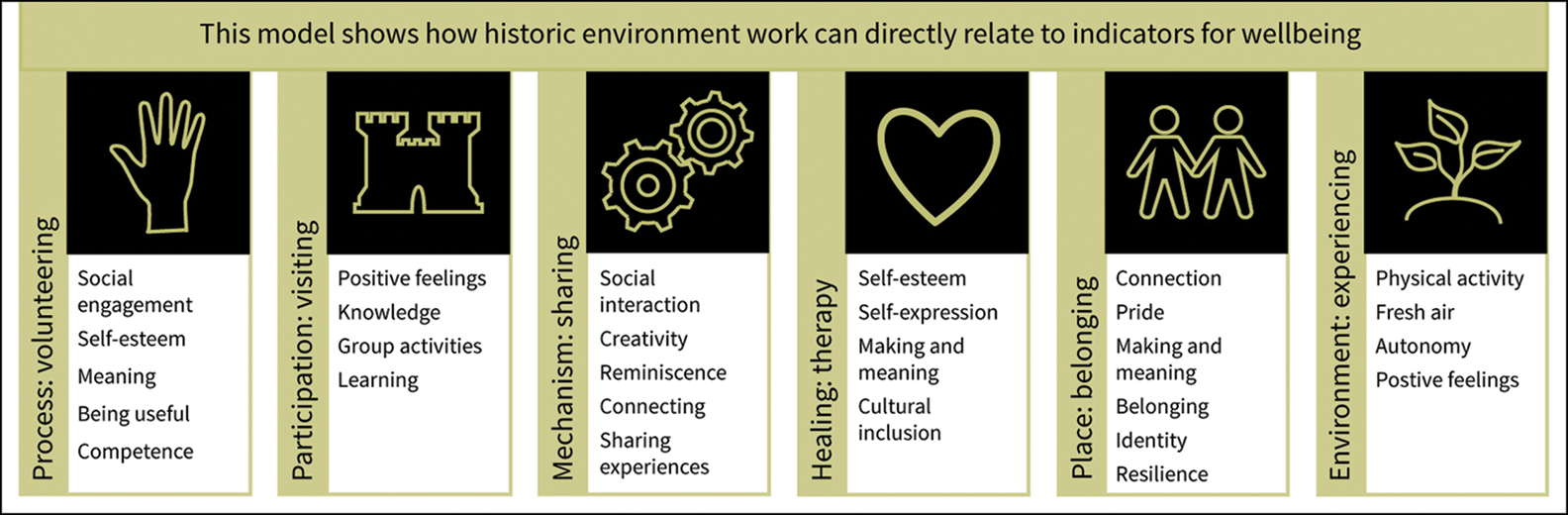

For example, earlier this year, Historic England, the body responsible for protecting England's historic environment, published a report on how the organisation might engage with wellbeing and social prescribing.Footnote 9 This explores a variety of ways in which heritage can feed into the wider wellbeing agenda including through visiting and experiencing sites and landscapes, volunteering and opportunities for sharing and belonging, as well as therapy and healing (Figure 1). What all of these reports and recent publications share is an emphasis on the complexity of such work in terms of resources, expertise, training, sustainability and safeguarding—social prescribing is no quick fix. There is also an emphasis on supplementing anecdotal impressions about the value and success of such programmes with robust empirical evidence. To that end, Historic England has announced co-funding for a number of trial projects to assess the possibilities and challenges of leveraging the power of the historic environment to address wider societal challenges. The funding will support community projects that help people connect with heritage and local environment through art, culture and physical activity in order to address a range of mental and physical health issues and wider socio-economic inequalities.

Figure 1. Wellbeing and the historic environment (figure © Historic England).

The Historic England report observes that one of the key challenges around developing a successful social-prescribing programme will be to address perceptions that the wellbeing agenda is distinct from the organisation's traditional statutory responsibilities to protect and promote archaeology and the historic environment. Any such concerns about whether archaeology should be involved in these activities must be understood in relation to wider questions around ‘public value’ that are now accelerating, not only in relation to government organisations such as Historic England, but also within the commercial archaeology sector.Footnote 10 Recent studies have questioned the public benefit and value derived from state funding spent on commercial archaeology, and highlighted how developer-led practice and outcomes have stripped away much of the very meaning—the magic—that attracts people to the discipline in the first place, both professionally and the wider public.Footnote 11 Even if COVID-19 is not the cause it may be a significant factor in focusing attention on these rumbling questions about the purpose of archaeology, both academic and commercial, about the value and meaning that it generates, and for whom these outcomes are intended.

Most of the examples discussed here focus on the UK, but the phenomena described have wider context and relevance. For example, a recent study has examined the therapeutic potential of archaeology in relation to descendant communities in North America,Footnote 12 and the concept of ‘engaged archaeology’ can already point to a variety of global examples.Footnote 13 The precise objectives and approaches of such research and engagement will inevitably vary by context—the preventative motivations of social prescribing may sit awkwardly in countries with private rather than state-funded healthcare systems, for example—but the wider questions of value, purpose and relevance will only grow as the world (eventually) emerges from the pandemic.

Antiquity Prize and Ben Cullen Prize 2021

![]() Last year, in 2020, Antiquity published more than 80 research articles, covering a wide and varied range of periods, regions, themes and approaches. Authors reported on archaeological research undertaken in dozens of countries and regions, and ranging in time and theme from Pleistocene hunter-gatherers to contemporary archaeology. The quantity and diversity of all of this material can make it difficult to observe trends, but a couple of noticeable currents include the revisiting of well-investigated sites or site types with new techniques, helping in particular to refine chronologies, and studies connected with anthropogenic impacts on climate and environment, both past and present. It is from among this great variety of research published last year that our editorial advisory board and the Antiquity Trustees have selected two articles for the award of the 2021 Antiquity Prize and the 2021 Ben Cullen Prize.

Last year, in 2020, Antiquity published more than 80 research articles, covering a wide and varied range of periods, regions, themes and approaches. Authors reported on archaeological research undertaken in dozens of countries and regions, and ranging in time and theme from Pleistocene hunter-gatherers to contemporary archaeology. The quantity and diversity of all of this material can make it difficult to observe trends, but a couple of noticeable currents include the revisiting of well-investigated sites or site types with new techniques, helping in particular to refine chronologies, and studies connected with anthropogenic impacts on climate and environment, both past and present. It is from among this great variety of research published last year that our editorial advisory board and the Antiquity Trustees have selected two articles for the award of the 2021 Antiquity Prize and the 2021 Ben Cullen Prize.

The Antiquity Prize goes to Emma Pomeroy, Paul Bennett, Chris Hunt, Tim Reynolds, Lucy Farr, Marine Frouin, James Holman, Ross Lane, Charles French and Graeme Barker for their article reporting on the ‘New Neanderthal remains associated with the ‘flower burial’ at Shanidar Cave’.Footnote 14 The site of Shanidar, in Iraqi Kurdistan, is of signal importance for our understanding of Neanderthals. The site was originally excavated in the 1950s by a team led by Ralph Solecki and quickly gained attention for the number of Neanderthal individuals discovered and for the evidence that they provided for compassion and care for the sick. Solecki suggested that some of the Neanderthal individuals had been killed by roof collapse; others, he argued, were intentionally buried, interpreting the presence of pollen to indicate the inclusion of flowers as part of the mortuary ritual. As the authors point out in their winning article, the interpretation of the evidence in favour of the inclusion of flowers with the burial of the Shanidar-4 individual has been subsequently contested. Nonetheless, Solecki's efforts to challenge the alterity of Neanderthals and to find greater similarities with our own species than previously allowed are tentatively backed by the latest finds from Shanidar—supporting the interpretation of intentional burial—and by wider recent studies that have sought to ‘humanise’ Neanderthals, finding them cognitively complex and kindred.Footnote 15

The 2021 Ben Cullen Prize is awarded to Debby Sneed for her article on ‘The architecture of access: ramps at ancient Greek healing sanctuaries’.Footnote 16 Stone ramps are a common feature of temples and sanctuaries across the ancient Greek world, but they are particularly common at religious sites dedicated to healing cults. By adopting a perspective informed by disability studies, the article sets out the case for the intentional design and construction of ancient architectural spaces to facilitate the participation of people with impaired mobility. The author is careful to emphasise that this does not mean that disabled ancient Greeks benefited from ‘civil rights’. Rather, the aim is to encourage us to look again at familiar sites and how they were used and experienced, and more generally to examine our implicit assumptions about the physical abilities of people in the past and about past attitudes towards disability. The healing sanctuaries of ancient Greece and a number of other societies are well known for the deposition of anatomical votives—clay, or sometimes metal, representations of afflicted body parts offered to the gods in the hope of divine intervention, perhaps a cure for an eye infection or for infertility (Figure 2). It is interesting to compare these place-based rituals in search of physical healing with some of the social prescribing work around the contemporary therapeutic value of monuments and landscapes outlined above. Scholars have tended to interpret these anatomical votives with physical ailments, but might some of these objects have been dedicated to the gods in search of improved mental health?

Figure 2. Bronze votive eyes of Roman date (200 BC–AD 100) (photograph © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum (CC BY 4.0)).

Both winning articles can be freely accessed online, along with an archive of all the previous winners, at https://antiquity.ac.uk/open/prizes. As noted above, these two articles come from a pool of dozens of other excellent contributions published last year, and another metric of success is the record-breaking number of downloads from our Cambridge Core platform in 2020. Collectively, there were over 650 000 downloads, and readers are invited to explore the ten most downloaded articles for free via a special collection on our website.Footnote 17 The articles include research on Doggerland, a new mammoth-bone structure at Kostenki 11, a Phoenician wine press in Lebanon, a complete GPR survey of the Roman city of Falerii Novi, the identification of a new Nordic Iron Age central place and an intact Inca underwater offering from Lake Titicaca. Our congratulations to the authors of both the winning articles and to all of those who published in last year's volume, helping to make it our most downloaded to date.

In this issue

![]() Articles in the current issue span from lithic tools in Late Pleistocene Tibet to the culture-hero mythologies of the Torres Strait practised through to the nineteenth century AD. En route we take in new evidence for early salt production in Neolithic Britain and the rediscovery in the National Museum of Denmark of the human bone excavated in the nineteenth century from the Bjerringhøj Viking Age burial. Networks are explored from two very different perspectives: an analysis of intervisibility between medieval strongholds in the Garhwal Himalaya of India and through the concept of ecological food webs using examples from North America. We also feature three articles focusing on key elements of the Eastern Mediterranean Bronze Age: copper metallurgy on Cyprus, Minoan palaces on Crete and the early development of alphabetic script in the Levant. Another article returns to investigate a topic that featured in the very first volume of Antiquity. In 1927 RAF Flight Lieutenant Maitland reported on extensive and complex stone arrangements across the Jabal al-Druze, identified during flights along the Cairo to Baghdad airmail route;Footnote 18 these walls and structures were known to the local Bedouin people as ‘the works of the old men’. Systematic aerial photography and, more recently, satellite imagery have dramatically expanded our knowledge of the extent and variety of these ‘works’ across the Middle East and beyond. In this issue, Thomas et al. report on a new programme of investigations relating to one particular category of these sites, mustatils (or rectangles), including new analysis of remotely sensed imagery, ground-truthing and dating.

Articles in the current issue span from lithic tools in Late Pleistocene Tibet to the culture-hero mythologies of the Torres Strait practised through to the nineteenth century AD. En route we take in new evidence for early salt production in Neolithic Britain and the rediscovery in the National Museum of Denmark of the human bone excavated in the nineteenth century from the Bjerringhøj Viking Age burial. Networks are explored from two very different perspectives: an analysis of intervisibility between medieval strongholds in the Garhwal Himalaya of India and through the concept of ecological food webs using examples from North America. We also feature three articles focusing on key elements of the Eastern Mediterranean Bronze Age: copper metallurgy on Cyprus, Minoan palaces on Crete and the early development of alphabetic script in the Levant. Another article returns to investigate a topic that featured in the very first volume of Antiquity. In 1927 RAF Flight Lieutenant Maitland reported on extensive and complex stone arrangements across the Jabal al-Druze, identified during flights along the Cairo to Baghdad airmail route;Footnote 18 these walls and structures were known to the local Bedouin people as ‘the works of the old men’. Systematic aerial photography and, more recently, satellite imagery have dramatically expanded our knowledge of the extent and variety of these ‘works’ across the Middle East and beyond. In this issue, Thomas et al. report on a new programme of investigations relating to one particular category of these sites, mustatils (or rectangles), including new analysis of remotely sensed imagery, ground-truthing and dating.

As ever, we trust that there is something of interest for everyone among the full line-up of research articles in this issue. We also have six new Project Gallery articles available on our website, covering archaeological research in Europe, China, India and the Maldives. If you would like to see your own research featured in the pages of Antiquity, you can find all of our submission guidelines and policies online at: http://antiquity.ac.uk/submit-paper. We are happy to discuss ideas for papers, to answer any questions about the submission process and to receive suggestions for topics that we might feature. Do please get in touch: https://www.antiquity.ac.uk/contact