The landscape is like a historic library of 50,000 books … some of the languages are still unknown. (Rackham Reference Rackham1986: 29–30)

Introduction

Cyril Fox's influential volume The archaeology of the Cambridge region was first published in 1923. Its centenary provides an appropriate occasion to consider how approaches to landscape studies and settlement densities have changed over the years. Here, we offer an experiment in site-density data. Employing Fox's study as a datum, our aim is to draw attention to the high-density settlement patterns identified through 30 years of development-related fieldwork in the Cambridge region and the resulting flood of archaeological data. In particular, such landscape-scale investigations now have the potential for the near-total recovery of archaeological settlement patterns. The resulting high site densities raise pressing socio-economic and environmental questions concerning the ways in which material culture and ideas were shared and natural resources exploited. The similar rise of development-led archaeology and the application of landscape-scale evaluation in many other parts of Europe and further afield is leading to a greater appreciation of the complexity of early settlement networks; in this article, brief comparisons are made with other landscapes in Southern Britain and Western Europe. There is also a broader historiographical dimension to our study. Fox's approach to the archaeology of the Cambridge region laid the foundations for his later book The Personality of Britain (1932). The broad characterisation of Britain into Highland and Lowland landscapes articulated there has cast a long shadow over studies of Britain's past (e.g. Gosden & Green Reference Gosden and Green2021: 108–9), influencing regional and landscape archaeologies more generally.

Mapping: an engine of research

Ground breaking in its time and widely influential, first and foremost Fox's book has been a major resource for regional research in South East England (Figure 1A). In acknowledgement of its contribution, the Cambridge Archaeological Unit (CAU) has initiated its own ‘New Archaeologies of the Cambridge Region’ series, with three volumes published to date (Evans et al. Reference Evans, Mackay and Webley2008, Reference Evans, Lucy and Patten2018; Evans & Lucas Reference Evans and Lucas2020). Fox's study focused on an approximately 1900-square-mile (3058 km2) ‘frame’, centred on Cambridge and extending for 20–25 miles (32–40km) beyond the city, encompassing portions of adjacent counties (Figure 2A–C). A retrospect on the volume by its author (Fox Reference Fox1947), and a biography of Fox (Scott-Fox Reference Scott-Fox2002), provide further details of the survey's background and methods.

Figure 1. Fox's volume set upon its Roman Age map (A; photograph by D. Webb); B) Cambridge-area map showing extent of major development-led evaluation areas since 1990 (B); NWC indicates North West Cambridge project-area; C) Davidson and Curtis’ Reference Davidson and Curtis1973 Iron Age map.

Figure 2. Location map showing The archaeology of the Cambridge region's area (A) and B) its relief and National Character landscape characterisation mapping (B shows Fox's ‘white/open’ land corresponding to the East Anglian Chalk); C) Fox's Bronze Age map.

In recent years, several ‘big data’ studies have used digital mapping to mobilise the now vast body of information generated by development-led archaeology in England (e.g. Rippon et al. Reference Rippon, Smart and Pears2015; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Allen, Brindle and Fulford2016; Gosden & Green et al. Reference Gosden and Green2021). Among the earliest attempts at such distributional research was a nineteenth-century initiative by the Society of Antiquaries of London (e.g. Evans Reference Evans1876, Reference Evans1893). Archaeological mapping, however, only came to the fore in the first decades of the twentieth century, with Fox (Reference Fox1947: 1–2) acknowledging the influence of O.G.S. Crawford, H.J. Fleure and J.P. Williams-Freeman. Yet, The archaeology of the Cambridge region was of an altogether different order. At 360 pages, it was much more comprehensive, with its approach considered to be unique in Europe (see Fox Reference Fox1947: 16 on Oswald Menghin's review; the title of this section (‘Engine of research’) derives from Clark's Reference Clark1933 review of Fox Reference Fox1932).

The volume was lavishly illustrated and Fox effectively crowd-sourced funding for the figures, raising £100. The visual material includes a set of accompanying period maps (plus nine maps reproduced in-text) and 37 plates showing material from the University Museum, many featuring five or more artefacts, amounting to a near-corpus of the region's findings at that time. Fox's main geographical and environmental sources were the Geological Survey and Tansley's (Reference Tansley1911) The types of British vegetation. Essentially corresponding to permeable chalk, greensand or sands, and gravel geologies on one hand, and impermeable clay soils on the other, Fox sub-divided the region into ‘open’ and forested lands. These areas were respectively portrayed in white and green on the maps (Figure 2B, C). Characterising them as areas of ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ settlement, Fox held that significant inroads were only made into the forested lands through “a certain standard of civilization” and really only occurred in Roman times (Fox Reference Fox1923: 224–5, 315).

Beyond these designations, Fox exercised further landscape caricature, with the middle/lower Ouse Valley deemed ‘cold claylands’. In contrast, the upper reaches of the valley and that of the River Cam—plus the Ivel and the eastern fenland borders—were appreciated as fertile ‘cornlands’; the lack of attested past activity from the fenland's marshes being attributed to malaria (Fox Reference Fox1923: 9, 312–15). Based on subsequent findings and environmental research, Fox modified his open and forested categories. In the 1948 edition, he saw their interrelationship as one of gradation, respectively areas of ‘easy’ and ‘difficult settlement’. Nevertheless, the potential of claylands for settlement was still severely underestimated (with the extent of forest cover exaggerated): Clay may have been the only, and therefore ‘primary’, soil on which man settled in a few areas but it must always and everywhere have been ‘difficult’; iron-hard in droughts and gluey in the rains (Fox 1948: 20).

Low-density pasts

The discussion that follows is largely confined to the archaeology of the Iron Age and Roman period (c. 700 BC–AD 400). For our comparative purposes, we focus on these periods as they are characterised by high settlement densities and, often enclosed by ditches, their identification is relatively straightforward when compared with those of earlier periods. Details of the published sources for the site distributions discussed here are provided in the respective figure captions. However, owing to the nature of the data (e.g. duplicate entries in overlapping datasets), the quantification offered here should be considered indicative of trends rather than taken as absolute values. Indeed, given the pace of development in the Cambridge region, still further sites will have surely come to light since this article was written.

First, though, consider Fox's Bronze Age map (Figure 2C), as it clearly expresses the dominance of the ‘white’ chalklands in the archaeological recording of the early twentieth century. Compared with the negligible finds from the heavy ‘green’ lands, more than 145 barrow symbols dot the length of the downlands up to the Brecks near Thetford. These barrows, in turn, were held to reflect the route of the Icknield Way, an early trackway running from Wessex to East Anglia along the chalk escarpment (see also Fox Reference Fox1923: Sketch Map D, and Evans et al. Reference Evans, Lucy and Patten2018: 424–5). Recovered during quarrying and peat-digging, a distinct cluster of Bronze Age finds lay west of the Cam, extending from Cambridge north towards Wicken. Amid the map's indications, however, there are just four marked as a ‘Living Floor/Settlement’, located approximately 15–25km apart. Fox and other early practitioners were clearly aware that this settlement record was incomplete. Yet they do not seem to have conceptualised its extent and it is therefore difficult to appreciate just what kind of pasts they envisaged. After all, gauging the ‘completeness’ of an archaeological sample is contingent upon expectation. Ethnographic studies or colonial administrative records could have informed Fox and other early-day researchers of comparative settlement densities among ‘tribes’ or peasant communities (e.g. Steel Reference Steel1955), but these were evidently not consulted.

With known settlements so widely spaced, the key question arose of how these sites could have shared rhythms of chronological change and material culture styles. How could distant ‘dot communities’ have been linked? Accordingly, transient metal smiths and potters served as mechanisms of transmission. Under the influence of palaeoeconomic approaches, in the 1970s and 1980s transhumant cycles also came to be widely invoked—at least for prehistoric periods—providing a deus ex machina explanation for the cultural integration of far-flung communities (Evans Reference Evans1987). The acceptance of low-density pasts was furthered by a belief that the prime landscape locations were largely occupied by extant historic villages and towns (e.g. Hoskins Reference Hoskins and Taylor1973). In turn, the long-term continuity of these settlements reinforced ideas about the limited number of other past sites. This perception only began to be seriously challenged with the impact of extensive aerial photography (Taylor Reference Taylor1973: 28–33) and investigations in advance of early motorway construction. By the later 1970s and 1980s came a realisation that there was ‘more’, with documented contemporaneous settlements only 0.5–2 miles apart (0.8–3.2km; Taylor Reference Taylor1985: 25).

A rare study of that era offering an explicit consideration of local settlement densities is a 1973 paper by Davidson and Curtis on an Iron Age site at Trumpington's Plant Breeding Institute. Based on its discovery settlement, amounting to only the ninth such site then known within the Cambridge area, the authors boldly announced:

Supposing that all or most of the Iron Age sites in this area have now been located, we can consider the implications if they represent an approximation to the total economic exploitation of this area during that period. […] It is clear that there is a regularity of spacing of 1–11/2 miles (1.6–2.4km; Davidson & Curtis Reference Davidson and Curtis1973: 11; emphasis added).

Davidson and Curtis's map covered approximately 58km2 (Figure 1C). Today, the predicted number of Iron Age sites within that area would be in excess of 100: a more than tenfold increase (Evans et al. Reference Evans, Mackay and Webley2008: 183–6). This latter estimate derives from the results of extensive fieldwork arising from the extraordinary pace of development in the vicinity of Cambridge (Figure 1B). For several decades, hundreds of archaeological interventions every year have been undertaken across Cambridgeshire, making the city's environs one of the most intensively investigated areas within Britain (see Smith et al. Reference Smith, Allen, Brindle and Fulford2016: 386, figs 12.2 & 12.3). Development-funded fieldwork and, with it, the ability to sample-evaluate and excavate enormous tracts of land, is now common across much of Europe (e.g. Vander Linden & Webley Reference Vander Linden, Webley, Webley, Linden, Haselgrove and Bradley2012). The implications of the results of landscape-scale geophysical surveys and trial trenching are nothing less than revolutionary. While such techniques cannot recover all site types (e.g. biased to cut-feature archaeology), when compared with earlier fieldwalking surveys, for the first time there is the potential for near-total site recovery (Evans et al. Reference Evans, Mackay and Webley2008: 198–200 and see 181–6 for recent fieldwalking and cropmark recovery rates).

Within the Cambridge region, awareness of the potential archaeological significance of the claylands really only developed in the later 1990s. This appreciation was first prompted through investigations in advance of house building on the Isle of Ely and, then, more widely by aerial photography (Mills Reference Mills, Mills and Palmer2007) and during large-scale development north of Cambridge. Compared with gravel and chalk, the attraction of clay-based soils—for early communities having the plough technology to cope with them—was their fertility. These soils also have higher and more stable water tables compared with undeveloped or depleted gravel soils, which are more prone to summer drought. The delayed recognition of the extent of archaeology in the region's claylands is easily explained: heavy soils ‘lock in’ finds, making them less susceptible to detection during fieldwalking, and sites there are only rarely visible in aerial photography. In contrast, archaeological features in the ‘open lands’ have been much more readily apparent; regionally, the early detection of sites focused on the Cambridge chalk downlands, mirroring the situation in Wessex.

The land behind Cambridge

What constitutes a region? Potentially defined by geographical, environmental, political and historic land-use or other criteria, regions are not given. Fox's regional frame was centred on Cambridge, and its extent—determined by the 20- to 25-mile (32–40km) limit that could be reached by bicycle for site visits—maximised its geographical variability (Figure 2A–C). Recent national archaeological syntheses have used other definitions, and, accordingly, Fox's frame overlaps with theirs. Reading University's ‘Rural Settlement of Roman Britain’ project used Natural England's so-called ‘Natural Areas’, with the result that while most of Fox's region falls within their ‘Central Belt’, his chalkland-south portion lies in their ‘East Region’ (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Allen, Brindle and Fulford2016: 15–16, fig. 1.5; see also Rippon et al. Reference Rippon, Smart and Pears2015). In turn, although the former broadly corresponds with the ‘Central Province’ defined by Oxford University's ‘English Landscapes and Identities’ project (EngLaId; Gosden & Green Reference Gosden and Green2021: 56–7), intended to cross-cut set regions, their case-study transects bracket Fox's region (Green & Creswell Reference Green and Creswell2021: 2, 26).

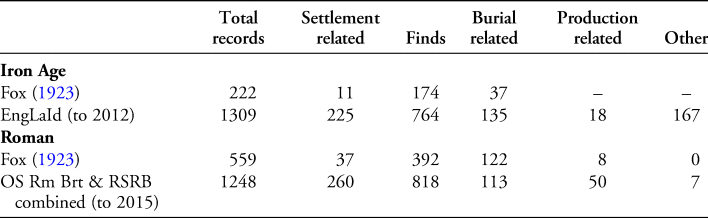

To appraise the degree of change in archaeological knowledge between Fox's time and the present, several case-studies are presented. Starting with the land around Cambridge, this involves the entirety of Fox's region. Therein, his 1923 map documents 222 Iron Age and 559 Roman-period entries (Figure 3, left). By 2010/2015 (see Table 1 for the basis of these data), based on aerial photography and fieldwork—including by the original Fenland Committee and later Fenland Survey programmes (Phillips Reference Phillips1970; Hall & Coles Reference Hall and Coles1994)—these numbers respectively had risen to 1309 and 1248: approximately six- and two-fold increases (Figure 3, right; Table 1). That said, Fox's map also includes hoards, spot-finds and other entries. If these are omitted, and comparisons restricted to the settlements, his numbers reduce to 11 Iron Age and 37 Roman-period sites versus 236 and 260 sites, respectively in the 2010/2015 dataset: the equivalent of approximately twenty-one- and seven-fold increases for the Iron Age and Roman period respectively.

Figure 3. Iron Age and Roman densities: left, after Fox's Reference Fox1923 mapping; right, as of 2010/15.

Table 1. The archaeology of the Cambridge region's Iron Age and Roman-period mapping: Fox (Reference Fox1923) information derived from Fox's Iron Age and Roman maps; EngLaId data (up to 2012) that summarises HER, Portable Antiquities Scheme and Historic England's NMP data into 1km ‘aggregated’ squares; OS Rm Brt—Ordnance Survey Roman Britain Map (1991)—showing the distributions of settlements, funerary and religious sites, production and finds distributions at the cusp of PPG16; ‘Rural Settlement of Roman Britain’ (RSRB) project entries derived from ADS data (up to 2015).

Aside from along the south-western fen-edge, much of this increase in attested settlement activity has been documented along the river valleys and their edges, primarily in advance of quarrying and the expansion of urban centres. The updated distributions could be read as comparable to Fox's high densities along the chalklands. Yet, crucially, this has generally not been upon the downs proper, but its north-western skirtland. Comprising a band of more mixed geology, its northern extent corresponds to the eastern fen-edge and, towards the south-west, the Cam Valley. Having more level, terrace-like relief, the foot of the downlands would have also offered abundant water-sources (i.e. aquifer spring-lines).

Where, for both periods, a significant difference occurs is across the clay soils north of Cambridge: the 1085km2 of the Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire claylands. There, the increases in the numbers of settlements recorded by Fox and in the 2010/2015 dataset are fifteen-fold for Iron Age sites (3 versus 45) and sixteen-fold for Roman sites (6 versus 96).

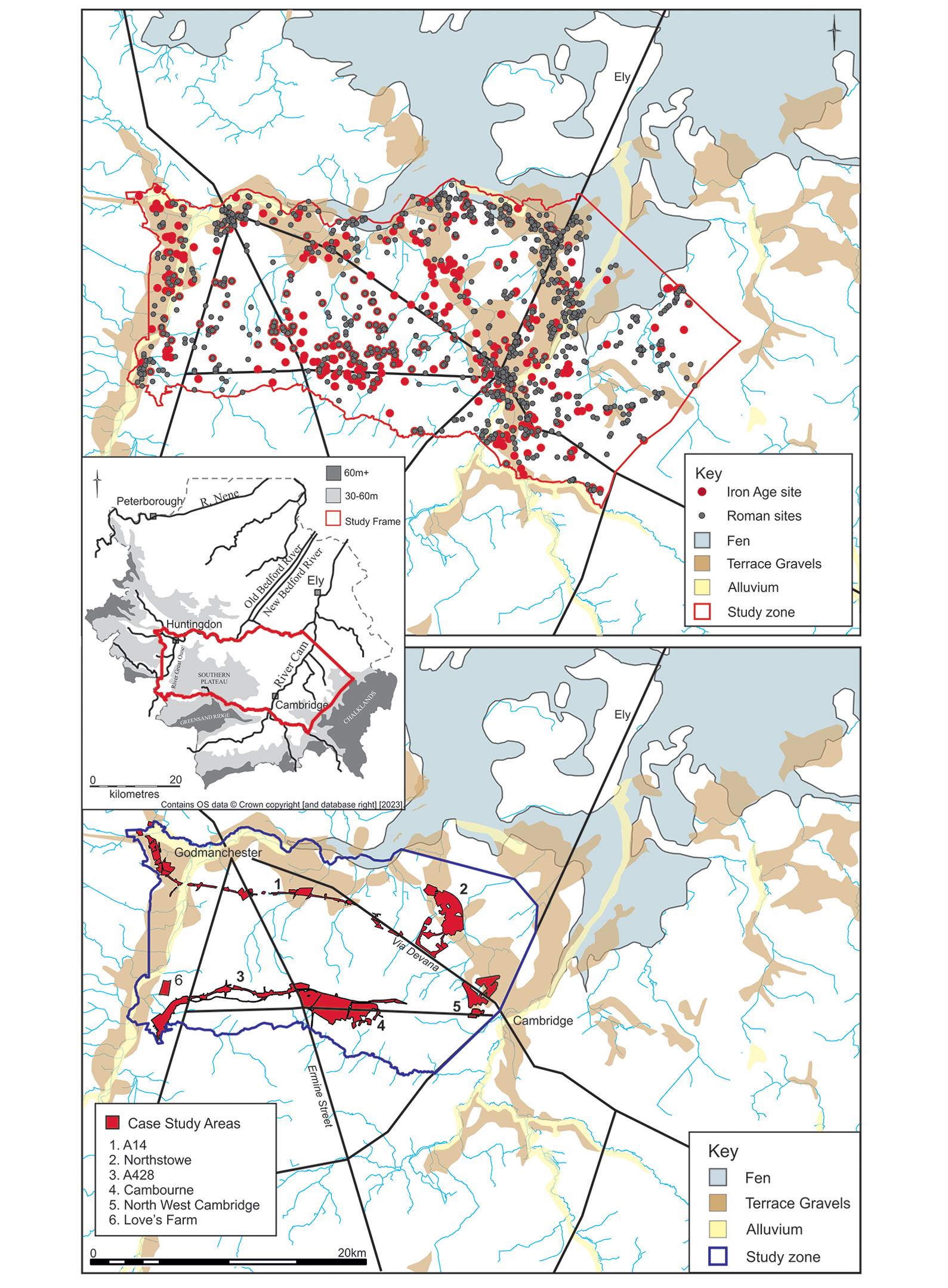

Although these increases demonstrate substantial rises in settlement numbers throughout the region, they still under-represent the current state of knowledge (i.e. excluding evidence collected post-2010/2015), especially across the northern claylands. Consequently, our next case-study focuses on a 383km2 swathe of the claylands north ‘behind’ Cambridge, encompassing all records from the Cambridgeshire Historic Environmental Record (HER; Figure 4, area outlined in blue). As of ‘now’ (2021), it has in the order of 415 and 590 Iron Age and Romano-British entries, respectively (not just settlements). However, through road-improvements and mass-scale house-building programmes, there six projects alone—together extending over more than c. 4074ha and amounting to a 10.6% area sample—contribute 103 Iron Age and 56 Roman sites, and indicate average square-kilometre densities of 2.5 and 1.4 settlements, respectively (Table 2).

Figure 4. ‘The Land behind Cambridge’, showing updated site distributions (to 2021), with main Roman roads indicated; below, with case-study areas highlighted (figure by authors).

Table 2. Six-project case-study settlement densities (* totals account for ‘overlapping’ Northstowe and A14 areas).

For the purposes of ‘framing’, that figure's mapping (Figure 4, top, red-outline) also shows the wider site distributions known along the fen-edge to the north and, to the south-east, in the Cam Valley and downlands. These, however, are excluded from the density calculations used here on the grounds that these areas have yet to be subject to intensive, large-scale evaluations and, therefore, do not offer a comparable statistical basis. Within this study area, bounded by the River Great Ouse in the north and its Ivel tributary to the west, investigations of the northernmost stretch of the modern A14 route, and, to the south, at Love's Farm perched on the edge of the clays above St Neots’ floodplain (Hinman & Zant Reference Hinman and Zant2018), emphasise the role of river transportation and its influence upon settlement densities. Indeed, Love's Farm has the highest Iron Age settlement density at four settlements per 1km2; the Roman-period level is also high, with near-continuous riverside settlement documented extending south from it (Hinman & Zant Reference Hinman and Zant2018: fig. 1.4; see also Evans et al. Reference Evans, Lucy and Patten2018: fig. 6.30).

Reflecting its Roman town-hinterland location, it is actually the Greater North West Cambridge area that had the highest Roman settlement density. By the same token, over much of their lengths, the A14 and A428's fieldwork closely followed the projected routes of major Roman roads: the A14, the Via Devana—linking Roman Cambridge and Godmanchester—and the A428 (running west from Cambridge), Margary's Road 231 (Evans & Lucas Reference Evans and Lucas2020: 202–3, figs 1.4 & 3.57; Abrams & Ingham Reference Abrams and Ingham2009). With Cambourne's new town adjacent to the latter route and its Ermine Street crossroads (Wright et al. Reference Wright, Leivers, Smith and Stevens2009), and Longstanton/Northstowe situated on an inland gravel terrace, none of the six-projects’ tracts amount to a ‘pristine’ claylands sample. While Cambourne's densities can be considered the most broadly representative, there will always be other factors, and geographical conditions are unlikely to have ever been the sole determinant of settlement. Acknowledging such caveats, and that averages invariably mask variability, we can calculate that some 957 Iron Age and 536 Romano-British settlements lay within the claylands’ ‘frame’ outlined in red on Figure 4 (top). Indicating a doubling of the known HER Iron Age entries for this area, this seems entirely plausible. So does, too, that the calculated total number of Romano-British settlements is approximately half that of the Iron Age. Yet, what of the discrepancy that our calculated figure for Romano-British sites is slightly less than the HER's figures (536 versus 590)? This can be explained by its duplicate same-site entries and because it also includes stray finds and not just settlements. The estimate based on the results of the six development projects can, therefore, be considered the more sound.

These claylands have alternatively been termed the Southern Plateau and Western Plain, reflecting the area's relief. Albeit a subtle topography, the area features small valley troughs and rises, and is bisected by streams and brooks. At points having mixed till-derived cover, the character of the clays varies from lighter Kimmeridge and Boulder Clay to the heavy Gault and Ampthill classifications; the latter were evidently avoided for settlement where possible. There are also ‘inland’ gravel terraces apparent in the distributions mapped along the route of the A14 works, where two-thirds of the Iron Age and Romano-British settlements lay densely packed on the gravels—amounting to less than half the route's length—while, on the clays, settlements were up to 4km apart (this, in part, reflecting ‘distortion problems’ of employing linear transects as a basis of area-representative samples).

Thus far, we have cited bald figures that take no account of variable period lengths or settlement duration. The Roman occupation of Britain lasted just over 350 years, compared with the approximately 750 years of the Iron Age. The latter's settlements are generally somewhat smaller than those of the Roman period (on average 1.3 versus 3.4ha, respectively, based on the results of the six projects). With plans ranging from sub-square to ovoid/circular—some elaborated by internal sub-divisions and/or concentric circuits—many of the Iron Age enclosures are, nonetheless, small and simple. Some yield only meagre material assemblages and were probably not permanently occupied, their use possibly related to livestock.

The Roman-period settlements also show significant variety. Employing the ‘Rural settlement of Roman Britain’ nomenclature (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Allen, Brindle and Fulford2016: 20–43), the majority are familial-scale farmsteads, with more than half having Iron Age origins. Other Roman-period sites fall into the more ‘complex’ farmstead category, whose larger plans often have further compound sub-divisions, plus a wider range of facilities and building types (e.g. aisled buildings, ritual settings, possible market functions). As well as a few known villas, there are also several large, village-sized roadside settlements (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Allen, Brindle and Fulford2016: 192–206).

In any mapping of settlement densities, the scaling of symbols must reconcile cartographic legibility with on-the-ground realities (Evans et al. Reference Evans, Mackay and Webley2008: fig. 4.8). This was an issue of which Fox was fully aware (1947: 7; see Figure 5). Also, distributions are calculated based solely on the centre points of settlements, when—given the variability of their footprints—it is the interval between contemporaneous sites that is paramount.

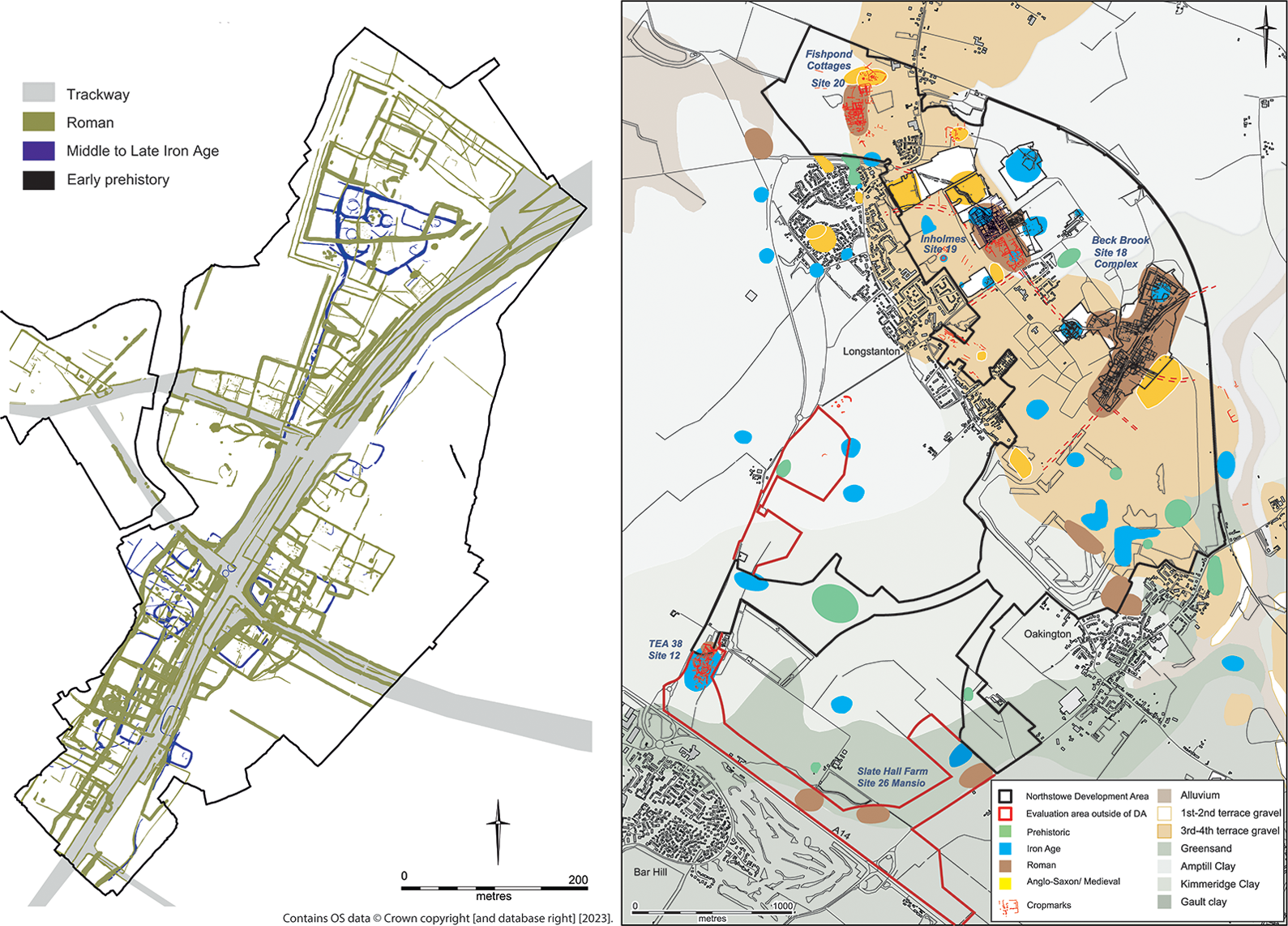

Figure 6. The Longstanton/Northstowe investigations, with detail of the Roman crossroads, perimeter-embanked Beck Brook settlement. (Note: on the left, only the Roman settlements are label-named as such, the remainder of the Roman indications are field systems.)

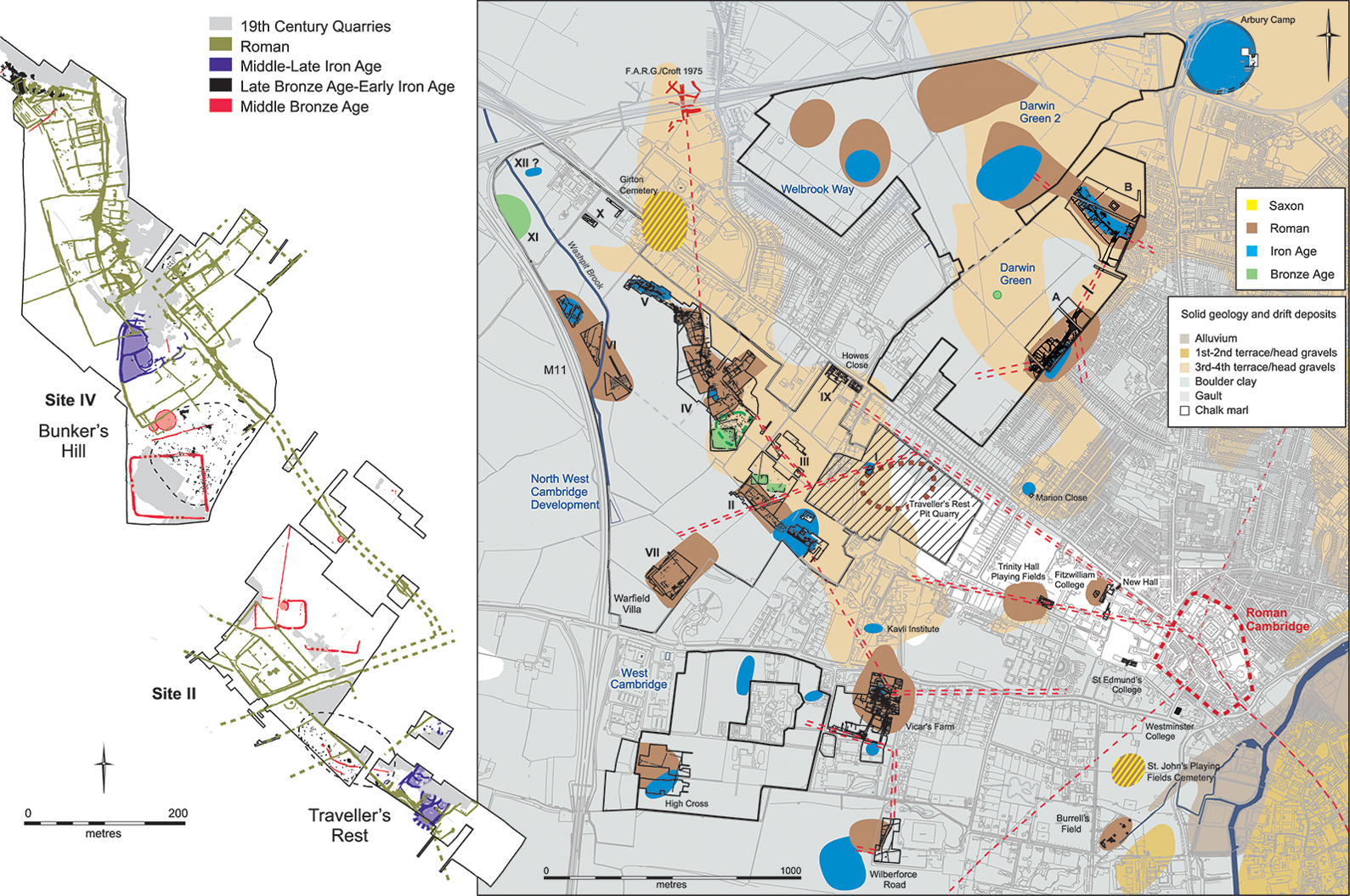

Figure 7. Greater North West Cambridge investigations and other west Cambridge sites; left: detail of main North West Cambridge ridge-top settlements (figure by authors).

While there are instances of Middle/Late Iron Age settlements ‘bunching’ in relation to local territory boundaries, they generally display relatively uniform distributions. Yet, where there was choice between gravels and clays, the Roman-period sites evince greater sensitivity to the possibilities of these soil types, preferring to locate settlement upon better-drained gravels and farming the more fertile adjacent clays. As a result, during the Roman period, portions of the inland gravel terraces were packed with settlement. In compensation for the necessary scale and ‘shape’ of their off-terrace agricultural holdings, there was then a greater interval stand-off with neighbouring settlements on the surrounding clays. This is evident in the mapping from the Longstanton/Northstowe and North West Cambridge investigations, which both straddle the same inland gravel ‘rise’ (Figures 6 & 7). In the latter area, Roman-period settlement was near-spatially continuous, including a major roadside complex (Bunker's Hill, Site IV). In contrast, at Longstanton/Northstowe, the Roman-period settlements were more widely spaced (c. 1km apart), but the three main ones were all very large (Aldred Reference Aldred2021: 111–55): in the north, Fishpond Cottages’ complex farmstead (4.3ha), then Inholmes, another of that designation (10.6ha), and, to the south, Beck Brook was an enormous crossroads settlement (16.5ha). Of a size rivalling that of contemporaneous small towns and featuring ‘quality’ buildings, the latter likely had an estate-administrative function.

Crucial is the much greater distance to the next-neighbour off-terrace settlements south-west of Longstanton/Northstowe. There, adjacent to the route of Via Devana/A14, the one saw both Iron Age and Roman-period occupation (TEA 38/Site 12); the other, a new Roman-period foundation, was probably a villa (Slate Hall Farm/Site 26; Evans et al. Reference Evans, Mackay and Webley2008: 174–81, figs 3.21 & 2.3). The intervening gap of 2–3km between the gravel terrace and these sites—probably used for agricultural production—was quite different from the situation in the Iron Age. Dotting the landscape more regularly and having an average spacing of approximately 400m, the earlier settlements display no equivalent clustering upon the gravels.

Near neighbours: high-density pasts

Fox and other early-day researchers could not have conceived of the scale of site densities identified by either the Longstanton/Northstowe or North West Cambridge projects. While the former's main Roman-period settlements would eventually be detected as cropmarks before development work, this was not true of the North West Cambridge area, and the full settlement densities in these ‘heavy lands’ have only been registered through recent multi-technique evaluation fieldwork.

The archaeology of the Cambridge region remains a remarkable achievement, drawing together a wealth of findings. In reference to Rackham's introductory landscape-as-library quotation, Fox's book greatly contributed to making the region's landscape more intelligible. Contingent upon the state of knowledge in the early twentieth century, today many of its interpretations are, of course, dated and explicitly reflect that era's emergent environmental/geographical determinism. Nevertheless, landscape remains archaeology's abiding interpretative framework, and Fox's study continues to prompt and focus thinking. Its basic land-use units—river valleys, the chalk and claylands—remain valid, each demonstrating distinct land-use histories. It is just that, unsurprisingly, Fox's chronology for the claylands was much too recent.

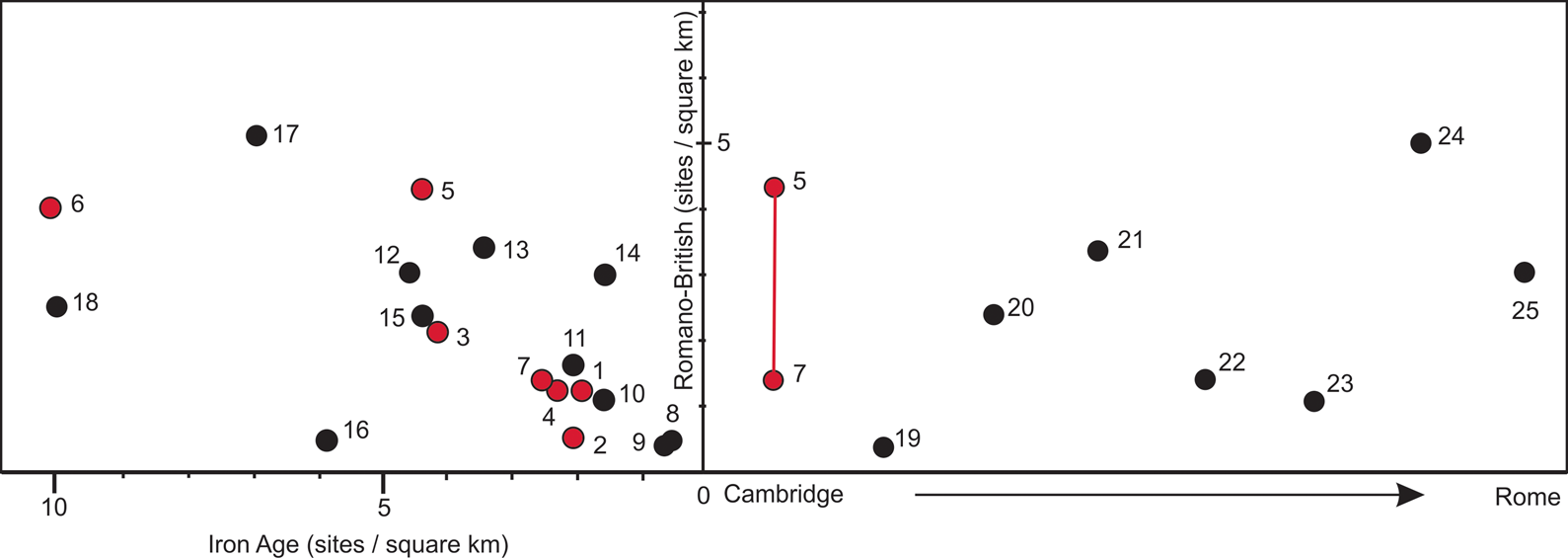

With so much excavation now undertaken, the past has become a far more complicated place. By no means are such high settlement densities as presented here restricted to the environs of Cambridge, and comparably high-density landscapes are now known across much of south and east England (Figure 8, left; e.g. Smith et al. Reference Smith, Allen, Brindle and Fulford2016: 21–2, 385–96; Aldred et al. Reference Aldredin press). Indeed, based on site numbers alone, some of its Roman-period settlement densities were as high as anywhere in the Northwestern Roman provinces, even if villas did not develop to the same degree (e.g. Fulford Reference Fulford2020); only the Auvergne region in France has produced evidence of higher densities (Trément et al. Reference Trément, Baret, Calbris, Regad, Wohlfarth and Keller2018; see e.g. Mattingly & Witcher Reference Mattingly, Witcher, Alcock and Cherry2016; Figure 8, right).

Figure 8. Plot showing both case-study (red dot) and selected Iron Age and Romano-British settlement densities (black dot; right); right, a transect of Roman North-western Provinces settlement densities (per km sq), from Cambridge to Rome's hinterland: 1) A14; 2) Longstanton/Northstowe; 3) A428; 4) Cambourne; 5) Greater North West Cambridge; 6) Love's Farm; 7) Six-project averages; 8) HS2, London to Birmingham (omitting Chilterns); 9) HS1, Kent; 10) Yarnton, Oxfordshire; 11) Broughton, Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire; 12) Cedars Park, Stowmarket, Suffolk; 13) Marsh Leys, Bedfordshire; 14) A1(M), Alconbury to Peterborough; 15) Hinkley Point, Somerset; 16) Greater Western Park, Didcot, Oxfordshire; 17) A120, Essex; 18) Claydon Pike, Gloucestershire; 19) Lower Rhine; 20) West Cologne/Rhine (and present-day Bergheim); 21) Seine-Normandie Basin; 22) Amiens (north-west sector hinterland); 23) Metz (southeast-sector hinterland); 24) Limagne Plain, Auvergne; 25) Rome Early Imperial-period suburbium (within 50km radius); see online supplementary material for sources and basis of inclusion (figure by A. Hall).

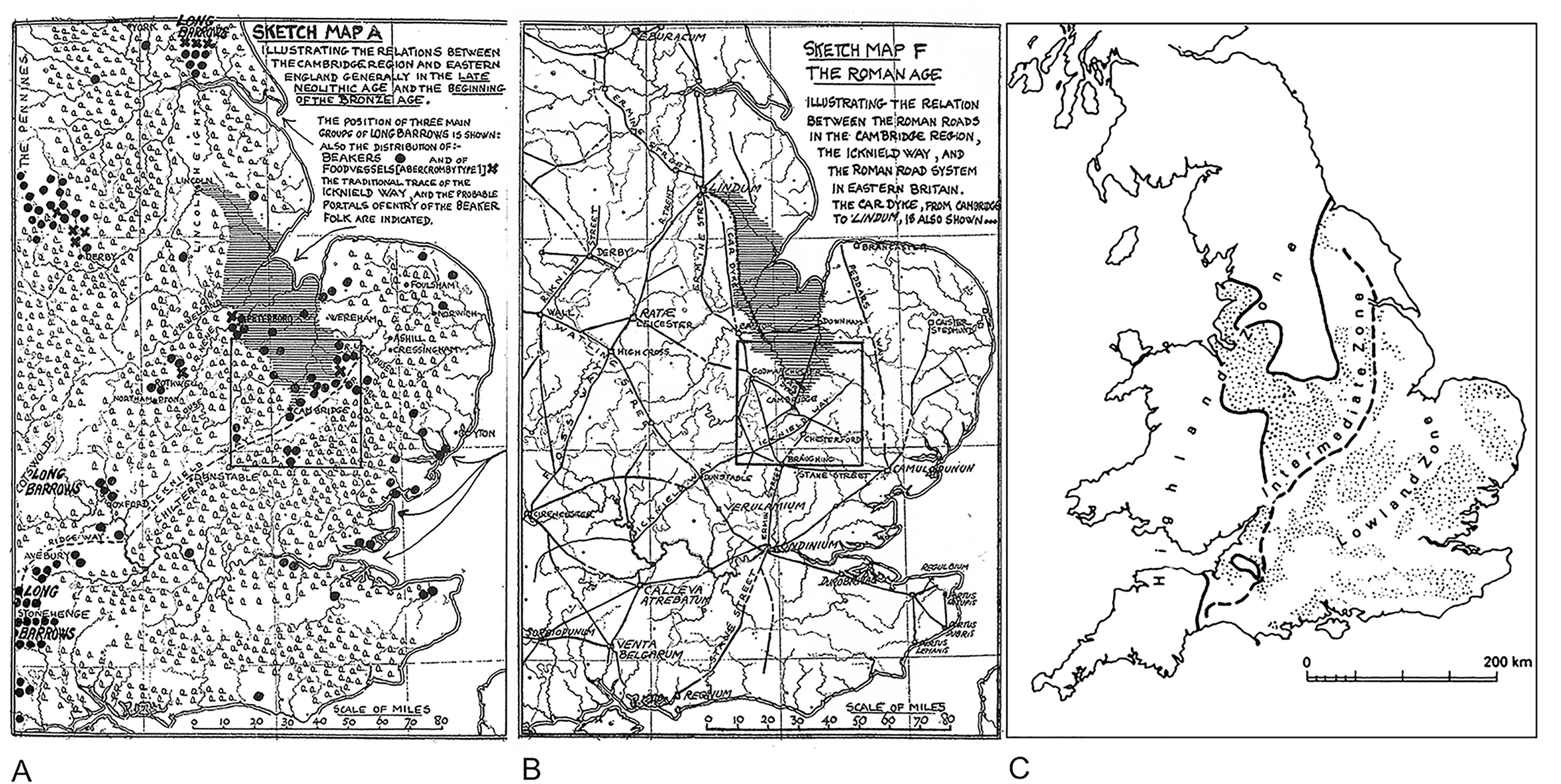

As distribution maps fill with dots, gone are the days of simple either/or patterning, and, understandably, there might be a nostalgia for a time when matters were seemingly more straightforward. For example, Fox's neatly geometric Roman roads are a far cry from the lattice of routes attested by the North West Cambridge project (though, see Fox Reference Fox1923: 319–20; Figure 9B). Similarly, Fox's annotation of his Sketch Map A, to provide an indication of the ‘Beaker Folk's’ arrival via the Wash—and the presumed long-distance connections facilitated by the Icknield Way—conveys a sense of narrative and even regionalities to his tightly clustered Beaker groupings (Figure 9A). Now, however, as the dots accumulate and ‘everything is everywhere’, it is almost as if we lose our ‘voice’ and the ability to convey ‘easy stories’.

Figure 9. Landscape caricature: Fox's maps illustrating Late Neolithic and earlier Bronze Age findings (A)—notice the bunched Beaker ‘dots’ and extent of forest cover—and main Roman centres and roads (B); Pounds’ (Reference Pounds1994: fig. 1.1) amended version of Fox's Reference Fox1932 Highland/Lowland Zone map showing intermediate Midland Zone, with stippling indicating heavily wooded lands (C).

Pending a comprehensive regional review, the challenges posed by such site numbers currently make it impossible to update Fox's study with complete confidence. Not only is there just ‘too much’, but also insufficient recent investigation of some areas. The downlands, for example, are well served by comprehensive aerial photographic coverage (Knight et al. Reference Knight, Last, Evans and Oakey2018), but there has been insufficient excavation to modern standards. Trends and propensities are, however, apparent as we begin to grasp the dynamics of the claylands’ colonisation. Substantial Neolithic settlements have yet to be identified on the claylands; nor are any early monuments such as barrows or henges known there. The Middle Bronze Age generally marks the first significant human activity and, thereafter, the claylands witnessed relatively ‘light’ settlement until the widespread Middle Iron Age influx. The means by which groups came to know and, eventually, to settle these ‘heavy lands’ require further research, as do the area's extra-regional connections and the differing character of some of the clayland settlements.

In reference to David Clarke's Reference Clarke1973 Antiquity article, these collective findings arguably amount to a further ‘loss of innocence’. Based on vast-scale evaluation procedures, unknown in Clarke's time, an awareness of the sheer quantity of past settlement has now been achieved. This should be ‘game-changing’ (Evans Reference Evans, Jones, Pollard, Allen and Gardiner2012), but the implications have yet to be fully appreciated. When, over much of this region, people could have effectively waved to their neighbours, there is no longer a de facto need to evoke modes of mobility—wandering smiths or migrant potters—to account for widely shared material culture traits. Rather, the question of how such high settlement densities could have been maintained should command greater attention. Certainly, such densities have far-reaching implications, including the regulation of territory/property, resource management and sustainability (e.g. wood supply) and, potentially, disease transmission (human and animal). They should even reconfigure the attention so often given to nuancing immediate settlement-location choice; in these ‘landscapes of neighbours’, a settlement might be where it was simply because so many other suitable adjacent locales were already occupied.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2023.99

Acknowledgements

Issues raised here have greatly benefited through discussions with, and/or information provided by, Richard Bradley, Matt Brudenell, Stewart Bryant, Jay Carver, Paul Chadwick, Mike Court, Alex Davies, George Fox, Mike Fulford, Kasia Gdaniec, Chris Gosden, Mark Hinman, Neil Holbrook, Jody Joy, Paul Lane, Martin Millett, Steve Rippon, Steve Sherlock, Barney Sloane, Alex Smith, Simon Stoddart, Frédéric Trément, Marc Vander Linden and Leo Webley. Ruth Beckley of Cambridgeshire County Council was helpful in the provision of HER data, and Imogen Gunn and Melanie Horton Hugow facilitated access to the University Museum's Fox archives. Rob Wiseman greatly aided in this article's preparation; the skills of Andy Hall are apparent in its graphics, with Dave Webb providing its studio shot.

Funded by an Historic England Covid Relief grant, this study is part of a larger ‘Dynamic approaches to abundant landscapes: Iron Age/Roman settlement’ project (see Aldred et al. Reference Aldredin press) and, at Historic England, we have only been grateful for Helen Keeley's, and latterly Jenni Butterworth's, understanding and much-tried patience.