Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 September 2016

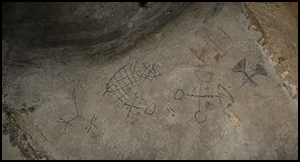

The rock art of the Lovo Massif region in the Lower Congo offers a fascinating and understudied example of artistic traditions, some of which predate the period of European contact. The first extensive, systematic survey of the region has identified key aspects of these rock art traditions, and has obtained radiocarbon dates that facilitate new interpretations of the relationship between the rock art and the historical kingdom of Kongo. Multiple perspectives are used to integrate anthropological, historical and archaeological data with stories from local mythology to show how the significance of this art has evolved over time. As a result of this study, the unique cultural heritage of the Lovo Massif rock art has been put forward for protection under the UNESCO World Heritage list.