Introduction

Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers dominate mass loss from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (Rignot and others, Reference Rignot2019) and are particularly vulnerable to climate forcings that threaten ice-sheet stability (Hughes, Reference Hughes1981; Joughin and others, Reference Joughin, Smith and Medley2014). Subglacial meltwater drainage is difficult to observe, but has a potentially critical control on ice-sheet behavior and evolution (Stearns and others, Reference Stearns, Smith and Hamilton2008; Creyts and Schoof, Reference Creyts and Schoof2009). Paleo observations have been used to infer hydrologic processes during ice-sheet retreat after the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) (Lowe and Anderson, Reference Lowe and Anderson2002, Reference Lowe and Anderson2003; Kirshner and others, Reference Kirshner2012; Nitsche and others, Reference Nitsche2013; Witus and others, Reference Witus2014; Simkins and others, Reference Simkins2017), though the mechanisms remain poorly understood, modeled and observationally constrained.

Ice-sheet reconstructions of Pine Island Bay (PIB) have shown that Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers were once merged into a single ice stream that was grounded to the outer shelf (Lowe and Anderson, Reference Lowe and Anderson2002; Evans and others, Reference Evans, Dowdeswell, Cofaigh, Benham and Anderson2006; Graham and others, Reference Graham2010; Jakobsson and others, Reference Jakobsson2011, Reference Jakobsson2012; Hillenbrand and others, Reference Hillenbrand2013; Nitsche and others, Reference Nitsche2013). Paleo-Pine Island Glacier is believed to have undergone episodic retreat following the LGM before splitting off into modern Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers (Kirshner and others, Reference Kirshner2012; Larter and others, Reference Larter2014). The first retreat phase, where the grounding line retreated from the outer shelf, occurred prior to 14.0 kcal yr BP and was followed by a series of back-stepping events after 10.6 kcal yr BP (Kirshner and others, Reference Kirshner2012; Larter and others, Reference Larter2014). Retreat across inner PIB is thought to have been driven by intense meltwater drainage events, driven by a change in basal conditions (Kirshner and others, Reference Kirshner2012; Witus and others, Reference Witus2014; Kirkham and others, Reference Kirkham2019), though the mechanisms remain poorly understood.

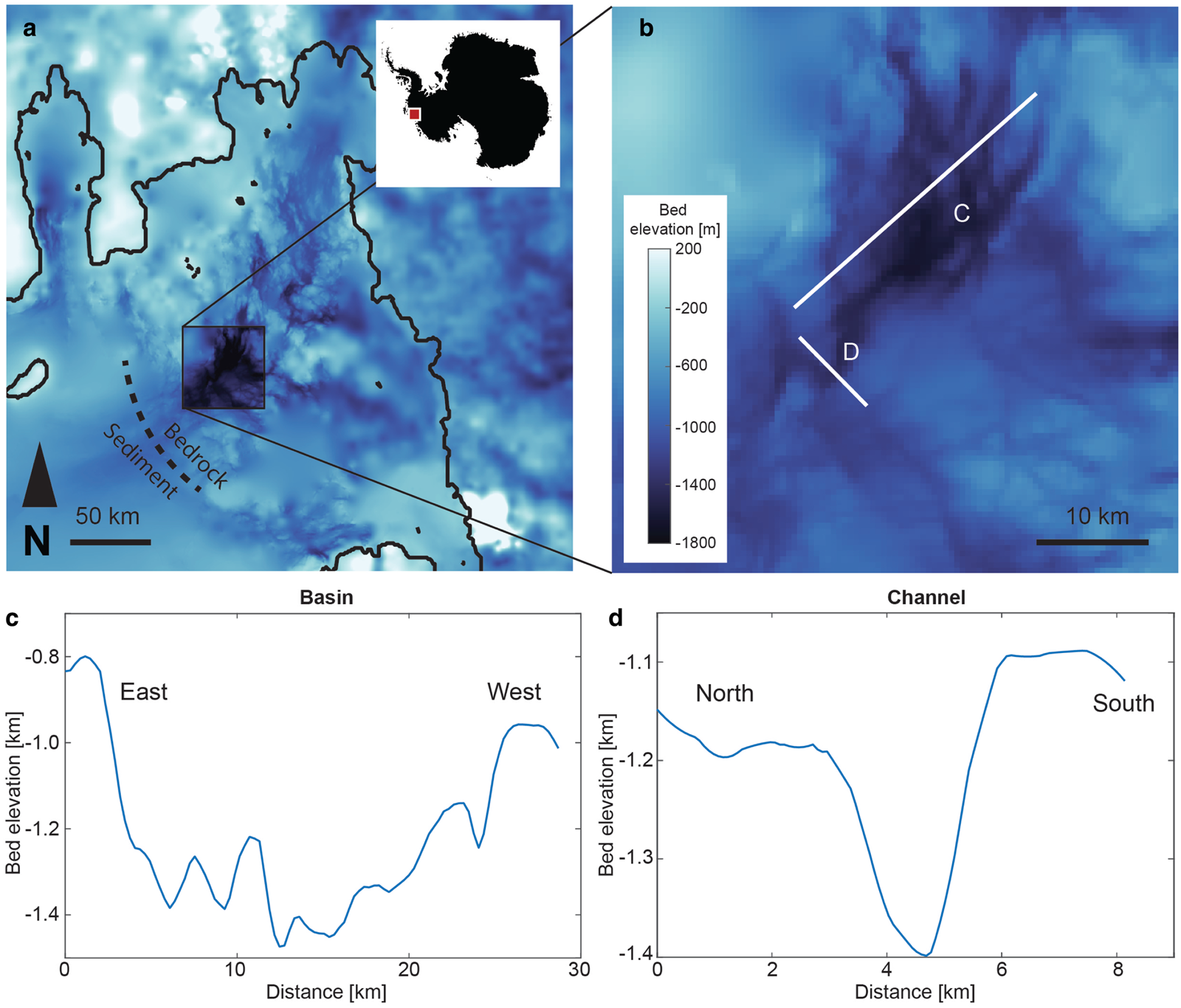

Marine geophysical and geological data in PIB have provided a framework for understanding the retreat and drainage system of paleo-Pine Island Glacier. Swath bathymetry and acoustic data of outer PIB reveal mega-scale lineations in soft till and grounding zone wedges extending to the continental margin of the Amundsen Sea (Evans and others, Reference Evans, Dowdeswell, Cofaigh, Benham and Anderson2006; Larter and others, Reference Larter2014). Inner PIB (Figs. 1a and b) is marked by a transition to a rugged bedrock basin and channel network (Lowe and Anderson, Reference Lowe and Anderson2002, Reference Lowe and Anderson2003; Nitsche and others, Reference Nitsche2013; Witus and others, Reference Witus2014). These basins are ~600 m deep (Fig. 1c) and several kilometers wide (Nitsche and others, Reference Nitsche2013; Witus and others, Reference Witus2014). Some are thought to have been occupied by paleo-subglacial lakes (Witus and others, Reference Witus2014; Kuhn and others, Reference Kuhn2017). The basins are connected by deeply incised (~250 m deep) anastomosing channels (Fig. 1d) up to 20 km long that are sometimes perpendicular to paleoice-flow direction (Lowe and Anderson, Reference Lowe and Anderson2003; Nitsche and others, Reference Nitsche2013; Witus and others, Reference Witus2014; Kuhn and others, Reference Kuhn2017; Kirkham and others, Reference Kirkham2019). The basin floors have linear and drumlin-like features and P-forms (Nitsche and others, Reference Nitsche2013), indicating that the basins were initially glacially carved and later modified by subglacial water flow from the channels (Lowe and Anderson, Reference Lowe and Anderson2002; Nitsche and others, Reference Nitsche2013).

Fig. 1. (a) Bathymetry of Inner PIB with sediment to bedrock transition (Arndt and others, Reference Arndt2013; Nitsche and others, Reference Nitsche2013; Witus and others, Reference Witus2014) including (b) bedrock basins with (c) an along-flow cross-section ~600 m deep and (d) an across-flow cross-section of connecting bedrock channels ~250 m deep.

The basins and channels appear to be organized into a large-scale subglacial drainage system hypothesized to have suppored intensive meltwater (e.g. Alley and others, Reference Alley2006) or outburst events (Lowe and Anderson, Reference Lowe and Anderson2003; Nitsche and others, Reference Nitsche2013; Witus and others, Reference Witus2014). The sinuous nature of the channels, P-forms and incisions around the bedrock drumlin heads provides additional evidence for significant meltwater drainage (Lowe and Anderson, Reference Lowe and Anderson2003; Nitsche and others, Reference Nitsche2013; Kirkham and others, Reference Kirkham2019). Morphological similarities to the Labyrinth – a collection of channels in the Transantarctic Mountains that were incised by high-discharge outburst floods (Lewis and others, Reference Lewis, Marchant, Kowalewski, Baldwin and Webb2006) – provide support for this interpretation (Nitsche and others, Reference Nitsche2013; Kirkham and others, Reference Kirkham2019). The channels in PIB cover an area of 400 times the size of the Labyrinth, which has been used to suggest that drainage events beneath the paleoice-stream were catastrophic (Kirkham and others, Reference Kirkham2019). Their deep incisions have led to the interpretation that the meltwater events must have been extremely high-volume (Nitsche and others, Reference Nitsche2013; Kirkham and others, Reference Kirkham2019) with discharge rates up to 8.8 × 106 m3 s−1 (Kirkham and others, Reference Kirkham2019), which were plausible during ice sheet formation (Alley and others, Reference Alley2006), but this is inconsistent with modern subglacial melt rates (Joughin and others, Reference Joughin2009; Nitsche and others, Reference Nitsche2013; Kirkham and others, Reference Kirkham2019). This idea has prompted the conjecture that subglacial volcanism or subglacial lake drainage may be responsible for increased paleo-melt rates (Nitsche and others, Reference Nitsche2013; Kirkham and others, Reference Kirkham2019). A recent investigation in the western Ross Sea has documented the existence of a large subglacial meltwater system that connects to subglacial lakes within an area of high heat flow; this system is known to have been active during the post-LGM retreat of the ice sheet from the continental shelf (Simkins and others, Reference Simkins2017) and resulted in the deposition of a unique meltwater facies on the outer continental shelf (Prothro and others, Reference Prothro, Simkins, Majewski and Anderson2018). These channels may also have formed over multiple glacial cycles (Lowe and Anderson, Reference Lowe and Anderson2003; Nitsche and others, Reference Nitsche2013; Kirkham and others, Reference Kirkham2019). The formation processes of these meltwater deposits could provide information on subglacial systems and ice-sheet history, but the mechanisms remain unresolved and may include a combination of tidal and sub-ice-shelf processes (e.g. Horgan and others, Reference Horgan2013; Christianson and others, Reference Christianson2016).

Acoustic, bathymetry and sediment core data show that outer PIB is overlain by sediment, while the inner PIB seafloor is predominantly crystalline bedrock with a thin or absent sediment cover (Lowe and Anderson, Reference Lowe and Anderson2003; Kirshner and others, Reference Kirshner2012; Gohl and others, Reference Gohl2013). It is hypothesized that retreat across the sediment/bedrock boundary increased the hydraulic potential near the grounding line and contributed to an increased water velocity and altered hydraulic regime (Witus and others, Reference Witus2014).

The stratigraphy and radiocarbon data from PIB sediment cores provide further evidence for acute changes in hydrological conditions during retreat (Kirshner and others, Reference Kirshner2012; Witus and others, Reference Witus2014). The uppermost sedimentary facies sampled in cores throughout PIB show an abrupt transition at about 7–8 kcal yr BP from a pebbly, sandy mud to a ubiquitous, well-sorted, silt-rich mud drape, referred to as Unit 2 and Unit 1, respectively, following the nomenclature of Kirshner and others (Reference Kirshner2012) and Witus and others (Reference Witus2014). Unit 2 is interpreted to be ice-proximal sediment deposited during retreat across the outer shelf, and Unit 1 is interpreted as a meltwater plume deposit termed an ice-distal plumite formed during the meltwater intensive retreat across inner PIB (Kirshner and others, Reference Kirshner2012; Witus and others, Reference Witus2014). Units 1 and 2 are separated by only 0.8 k yr (Kirshner and others, Reference Kirshner2012), suggesting that the transition from the ice-proximal to ice-distal facies must have occurred rapidly and therefore involved rapid grounding line retreat. The shift in deposition style is thought to coincide with the retreat of the grounding line across the sediment to crystalline bedrock boundary (Kirshner and others, Reference Kirshner2012; Witus and others, Reference Witus2014). Unit 1 is interpreted to have been mobilized and deposited by episodic meltwater intensive (Kirshner and others, Reference Kirshner2012; Witus and others, Reference Witus2014) or outburst events (Kirkham and others, Reference Kirkham2019). More recently, similar deposits that are believed to be modern plumites have been sampled beneath the modern ice shelf (Smith and others, Reference Smith, Gourmelen, Huth and Joughin2017).

Similar morphology and geology are present in Marguerite Bay, West Antarctica (Anderson and Fretwell, Reference Anderson and Fretwell2008). Marguerite Bay has a bedrock basin and channel network with sediment thickening towards the outer shelf (Anderson and Fretwell, Reference Anderson and Fretwell2008). This deposit is overlain by a thin mud drape with ages less than 10 kcal yr BP deposited during the Holocene retreat of the paleo-Marguerite Ice Stream (Kennedy and Anderson, Reference Kennedy and Anderson1989; Heroy and Anderson, Reference Heroy and Anderson2007). The striking similarities to PIB suggest that PIB and Marguerite Bay were shaped by similar processes.

Unit 1, the plumite layer in PIB described by Kirshner and others (Reference Kirshner2012) and Witus and others (Reference Witus2014), is broken into upper (1A), middle (1B) and lower (1C) subunits that are thought to represent episodic drainage (Kirshner and others, Reference Kirshner2012; Witus and others, Reference Witus2014). Subunit 1C is only present in inner PIB with radiocarbon ages ranging from 7 to 4.3 kcal yr BP (Kirshner and others, Reference Kirshner2012). Kuhn and others (Reference Kuhn2017) describe an older meltwater deposit from a basin in the inner shelf that yielded an age of 8.6 to 8.2 kcal yr BP. They did not observe the younger meltwater deposits identified in a basin located over 100 km farther to the north by Witus and others (Reference Witus2014). However, a single core collected by Witus and her colleagues farther to the south in a small isolated basin (TC 49), did sample meltwater units from Subunit 1A whose age is constrained by a single radiocarbon age of 1292 ± 1291 cal yr BP beneath the subunit and by 210Pb results that indicate a modern age for the upper part of this subunit. The ages and thicknesses of Unit 1 have been used to infer an average deposition rate of 0.002 cm yr−1 for the outer shelf basin (Witus and others, Reference Witus2014). Almost no age data are available for Subunit 1A, but 210Pb deposition rates are approximately 0.02 cm yr−1, an order of magnitude greater than Unit 1 as a whole, which has been used to suggest that Subunit 1A was deposited during a separate, higher energy event than Subunits 1B and 1C (Witus and others, Reference Witus2014).

Witus and others (Reference Witus2014) postulate that in order to achieve the fine sorting of Unit 1, sediment was deposited into the bedrock-incised basins prior to expulsion during an intensive drainage event. It is estimated that the total volume of Unit 1 is 120 km3, and that the basins in inner PIB can store 70 km3 of stagnant water (Witus and others, Reference Witus2014). This implies that there were multiple cycles of sediment deposition in basins and subsequent redistribution in order to match the 120 km3 sediment volume (Witus and others, Reference Witus2014).

Witus and others (Reference Witus2014) hypothesize that grounding line retreat across the bedrock basins caused a reorganization of the subglacial hydrology and drove the expulsion of sediment from the basins. They suggest that the sediment in these basins may have been pre-glacial and was redistributed across PIB through transport in the ice shelf water layer. However, it is still unclear how the sediment became sorted into the basins, how it was redistributed, and if drainage occurred in a steadyor punctuated manner. For example, a key challenge to validating the outburst or meltwater intensive hypothesis is reconciling the sedimentology of Unit 1 with subglacial outburst or high-energy drainage deposits. The high water velocities involved in a lake outburst are inconsistent with the fine sorting of Unit 1, based on our interpretation of Fredsøe and Deigaard (Reference Fredsøe and Deigaard1992) (unless the basin was already filled with nothing but silt). While there may be morphological similarities between the Labyrinth and inner PIB, the sedimentology is fundamentally different. The Labyrinth features imbricated clasts, graded bedding, cross-bedding and a wide range of grain sizes (Lewis and others, Reference Lewis, Marchant, Kowalewski, Baldwin and Webb2006), which are exceedingly rare in Unit 1 (Kirshner and others, Reference Kirshner2012; Witus and others, Reference Witus2014). So while the channel morphology has previously been used to invoke intensive drainage (Kirshner and others, Reference Kirshner2012; Witus and others, Reference Witus2014) or floods of epic proportions (Kirkham and others, Reference Kirkham2019), the water system conditions responsible for producing the silt deposit must be distinct from those required to carve the channels (Alley and others, Reference Alley2006).

In this paper we expand on the hydrologic reorganization idea proposed by Witus and others (Reference Witus2014) and put forward a mechanism by which this unit may have been scavenged, stored and deposited which can explain both the punctuated deposition implied by the deposition rate and the fine sorting of the silt unit itself. We demonstrate that this is a plausible mechanism given the ice-sheet conditions present during the late Holocene. We note our hypothesized mechanism is just one possible mechanism among others including the draining of lakes filled with presorted silt, the deposition of sub-ice-shelf silt plumites or the sourcing of sediments from silt-only regions.

Hypothesized mechanism

Our proposed mechanism for generating finely sorted, punctuated, silt deposition is based on transitions in the subglacial water system (Walder and Fowler, Reference Walder and Fowler1994; Creyts and Schoof, Reference Creyts and Schoof2009; Schoof, Reference Schoof2010; Schroeder and others, Reference Schroeder, Blankenship and Young2013; Andrews and others, Reference Andrews2014) that occurs as water flows from the upper catchment through bedrock basins (Nitsche and others, Reference Nitsche2013; Witus and others, Reference Witus2014) and as the grounding line retreats across those basins.

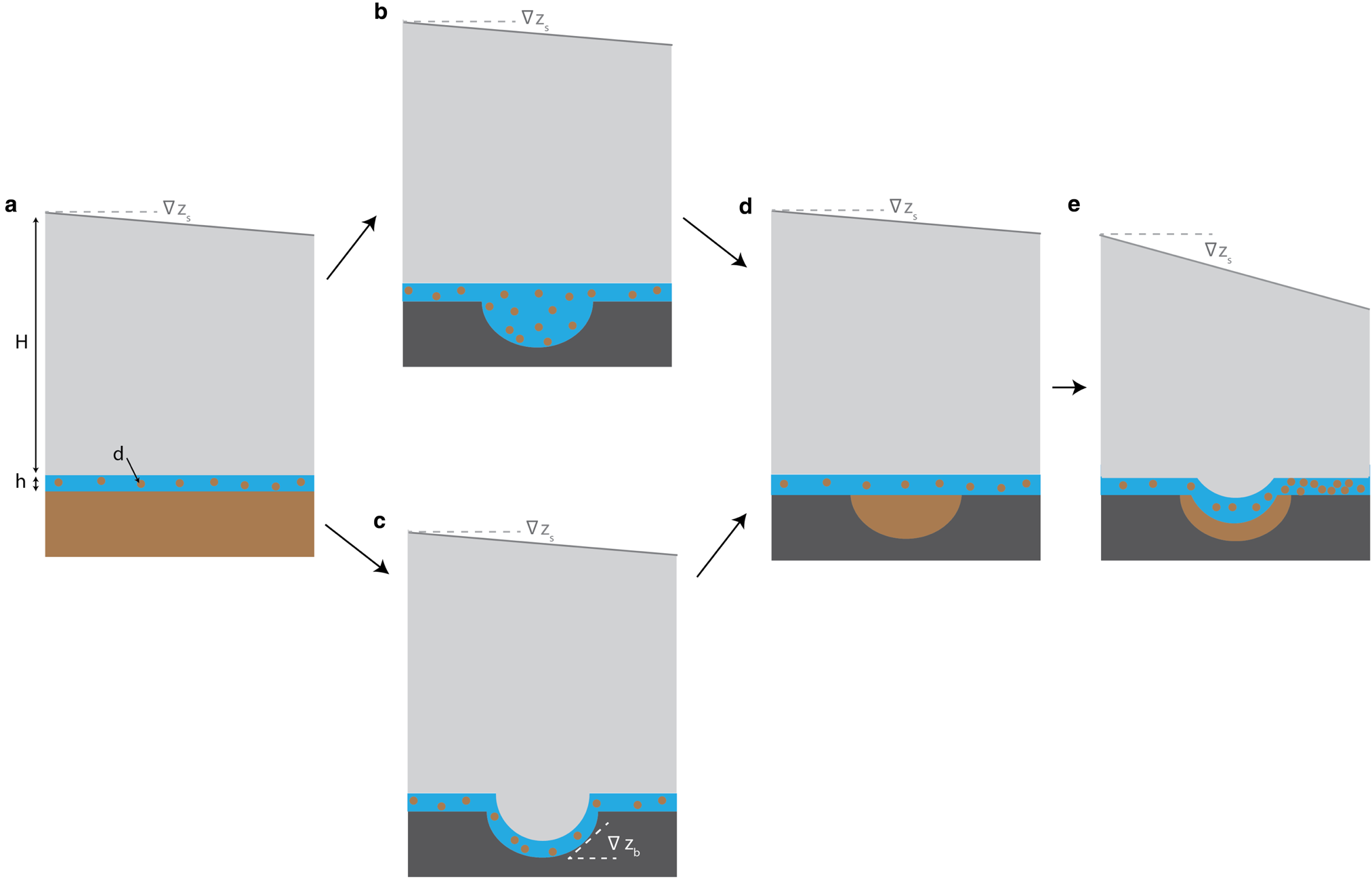

In the first stage of our proposed mechanism (Fig. 2a), slow moving water in a distributed subglacial system (Walder and Fowler, Reference Walder and Fowler1994; Le Brocq and others, Reference Le Brocq, Payne, Siegert and Alley2009; Creyts and Schoof, Reference Creyts and Schoof2009; Schroeder and others, Reference Schroeder, Blankenship and Young2013) flows between the base of the ice sheet and a bed of unsorted till across the interior of the Pine Island Glacier catchment. The low velocities of such a distributed system (Le Brocq and others, Reference Le Brocq, Payne, Siegert and Alley2009; Creyts and Schoof, Reference Creyts and Schoof2009) could transport only silt and clay, based on formulas from Fredsøe and Deigaard (Reference Fredsøe and Deigaard1992), effectively harvesting and sorting sediments with diameters below 10 μm from the unsorted till across the catchment. This stage of the proposed mechanism achieves the fine sorting of the observed silt units in PIB (Witus and others, Reference Witus2014), Marguerite Bay (Kennedy and Anderson, Reference Kennedy and Anderson1989) and Ross Sea (Prothro and others, Reference Prothro, Simkins, Majewski and Anderson2018) through the steady-state, slow-flowing water over a large area for a long period of time.

Fig. 2. Hypothesized process of silt unit sorting, storage and deposition including: (a) sorting and transport in a distributed water system over sediments in the ice-sheet interior, (b) deposition in bedrock basins that are host to subglacial lakes in the interior, (c) transport and deposition in a distributed water system flowing through bedrock basins with bed gradients up to $\nabla z_{\rm b}$ in the interior, (d) storage of sorted silt in bedrock basins and (e) erosion and deposition of stored silt from basins during retreat with increased surface gradients $\nabla z_{\rm s}$

in the interior, (d) storage of sorted silt in bedrock basins and (e) erosion and deposition of stored silt from basins during retreat with increased surface gradients $\nabla z_{\rm s}$ .

.

In the second stage of the mechanism, transport of that silt downstream by the distributed water system eventually flows through one of the bedrock basins (Fig. 1a) (Witus and others, Reference Witus2014; Nitsche and others, Reference Nitsche, Larter, Gohl, Graham and Kuhn2016) where the subglacial water velocity drops by an amount sufficient to deposit the silt (Fredsøe and Deigaard, Reference Fredsøe and Deigaard1992). This drop in velocity in the basin could occur for either of two reasons. (1) If the basin was host to a subglacial lake (Fig. 2b), the velocity would drop in the deeper water, leading to lake deposition (Hodson and others, Reference Hodson2016; Kuhn and others, Reference Kuhn2017). (2) Alternatively, if the distributed water system flowed through the topographic low of a bedrock basin (Nitsche and others, Reference Nitsche, Larter, Gohl, Graham and Kuhn2016) with an adverse bed slope that did not host a subglacial lake, was not yet filled with sediment (Creyts and others, Reference Creyts, Clarke and Church2013), and did not result in supercooling (Creyts and Clarke, Reference Creyts and Clarke2010) or sediment accretion (Winter and others, Reference Winter2019) (Fig. 2c) the water velocity would reduce (and the water layer would thicken) to the point that sediments are deposited in the steepest portion of the basin (Creyts and others, Reference Creyts, Clarke and Church2013). In either case, the deposition of silt could continue until the bedrock basins were partially filled with sorted silt (Fig. 2d). This stage of the mechanism stores the slowly accumulating silt in large enough quantities to produce the observed meter-scale silt deposits (Witus and others, Reference Witus2014) while still limiting the total volume of stored silt to the volume of the basins.

In the final stage of the model, the grounding line retreats towards the basin leading to enhanced local basal melting (e.g. Joughin and others, Reference Joughin2009), routing of upstream melt through bedrock channels (e.g. Le Brocq and others, Reference Le Brocq2013; Alley and others, Reference Alley, Scambos, Siegfried and Fricker2016) and increased subglacial water fluxes until velocities are high enough to erode the stored sediment (Fig. 2e) from the basins and deposit them on the continental shelf seaward of the grounding line. It is also possible that lake drainage (Stearns and others, Reference Stearns, Smith and Hamilton2008) or tidal fluxes (Horgan and others, Reference Horgan2013; Christianson and others, Reference Christianson2016) could remobilize the stored sediment, but our hypothesized mechanism does not include or require this.

In this mechanism, punctuated deposition and associated differences in deposition rates between Unit 1A and the rest of Unit 1 (Witus and others, Reference Witus2014) are the result of the finite storage of silt in basins available to be eroded once water velocities increase. In the following subsections of this paper, we do some simple calculations and argue that a physically plausible range of ice-sheet conditions can explain characteristics of the plumite deposit without invoking subglacial lake outbursts (e.g. Lowe and Anderson, Reference Lowe and Anderson2003; Jordan and others, Reference Jordan2010; Witus and others, Reference Witus2014; Kirkham and others, Reference Kirkham2019).

Silt sorting and deposition

Our proposed sorting, storage, erosion and deposition mechanism is based on the modulation of the subglacial water velocity by retreat and bedrock topography. Specifically, if the water velocity falls below the ‘settling velocity’ for a given grain size (Fredsøe and Deigaard, Reference Fredsøe and Deigaard1992) we assume that net deposition will occur. Similarly, if the velocity rises above the ‘critical shear’ velocity for a given grain (Fredsøe and Deigaard, Reference Fredsøe and Deigaard1992) size, we assume that net erosion (e.g. remobilization) and transport will occur. Finally we assume that if the subglacial water velocity between those values for a given grain size, only transport will occur.

Settling velocity

The settling velocity U s given by Fredsøe and Deigaard (Reference Fredsøe and Deigaard1992) is

where g is acceleration due to gravity (9.8 m s−2), d is grain diameter, C D is a drag coefficient (typically ~5 to 20 for fine sediments and which, for the purposes of this paper, we assume is constant) and s is a constant typically ~2.65 (Fredsøe and Deigaard, Reference Fredsøe and Deigaard1992).

Critical shear

The critical shear velocity U c given by Fredsøe and Deigaard (Reference Fredsøe and Deigaard1992) is

where α ~ 10 is a constant and μs = tan ϕ s is a property of the sediment and ϕ s is the static angle of repose for the sediment (~45°) (Fredsøe and Deigaard, Reference Fredsøe and Deigaard1992). Note that, for this paper, we (like Fredsøe and Deigaard, Reference Fredsøe and Deigaard1992) neglect cohesion, which would increase the velocities required to remobilize the stored silt.

Estimates of required velocities

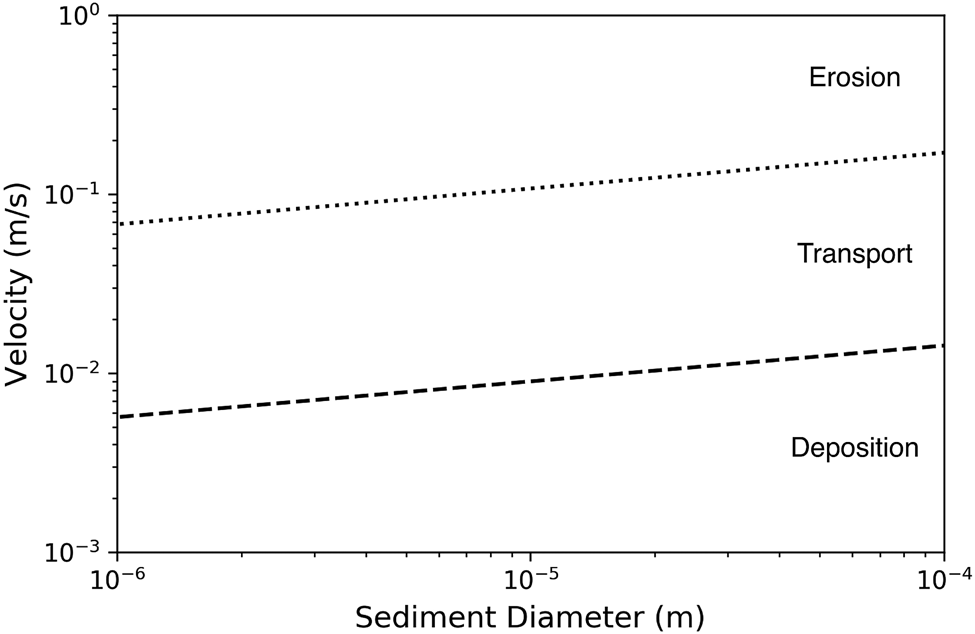

In order to estimate the range of velocities required for our hypothesized mechanism, Eqns (1) and (2) are plotted in Figure 3 (Hjulstrom, Reference Hjulstrom1955) for the range of diameters observed in Unit 1 (Table 1) (Witus and others, Reference Witus2014), noting again that we neglect the likely-significant effect of cohesion by using Fredsøe and Deigaard (Reference Fredsøe and Deigaard1992). With that caveat, assuming that silt is scavenged from only the top layer of the till, we estimate that velocities below ~10−2 m s−1 will lead to deposition, above ~10−1 m s−1 will lead to erosion and between will lead to transport. Therefore, our mechanism would need to produce upstream velocities (Fig. 2a) between ~10−2 m s−1 and 10−1 m s−1, then those velocities need to drop an order of magnitude or less below ~10−2 m s−1 in the bedrock basins (Fig. 2c) or lakes (Fig. 2b) and increase an order of magnitude or more to above ~10−1 m s−1 during retreat (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 3. Settling velocity U s (dashed line) and critical Shear speed U c (dotted line) as a function of sediment diameter for the range of diameters in Unit 1 (Witus and others, Reference Witus2014). Velocities below the dashed line lead to deposition, between the lines lead to transport and above the dotted line lead to erosion.

Discussion

Figure 3 shows that the silt unit in PIB could have been formed by transitions in the subglacial water system that occur over retreat across bedrock basins. Our mechanism includes velocities that need not exceed ~10–1 m s−1 during punctuated deposition (Witus and others, Reference Witus2014) and less than ~10−2 m s−1 during the comparatively quiescent periods (in contrast to outburst velocities that are on the order of 1–10 m s−1 (Lewis and others, Reference Lewis, Marchant, Kowalewski, Baldwin and Webb2006)). This is more consistent with the fine-grained, sorted lithology in PIB than an outburst mechanism, and it demonstrates that these silts could have been sorted at low velocities.

We attribute the fine, sorted deposits in Unit 1 to prior sorting in subglacial basins and subsequent redistribution at low velocities. Our proposed mechanism achieves sorting through a pervasive distributed upstream water system with low velocities on the order of 10−4 to 10−1 m s−1 (Fig. 3) that can transport only silt (or smaller grains) by harvesting small fractions of the silt from a large area of the catchment at a low rate over a long period of time (much of a glacial cycle if need be). From geophysical evidence we infer that a distributed drainage system is present beneath modern Thwaites Glacier (Schroeder and others, Reference Schroeder, Blankenship and Young2013), so it is plausible that such a system existed beneath paleo-Pine Island Glacier. Indeed, the pervasive occurrence of deformation till on the Antarctic continental shelf, such as in the Ross Sea, indicates that there was likely widespread dispersive flow at and within the bed (Halberstadt and others, Reference Halberstadt, Simkins, Anderson, Prothro and Bart2018).

The volume of the Unit 1 deposit (~120 km3) (Witus and others, Reference Witus2014) requires the sourcing of an average of less than 1 mm across the (184, 000 km2) catchment (Joughin and others, Reference Joughin2009). The silt sorting and transport by distributed water systems in our proposed mechanism could take place throughout the ice sheet, but the low rates and long time-scales would not lead to distinct silt deposits unless there were persistent bedrock basins to accumulate and sort the silt. Basins in inner PIB are estimated to have been able to hold up to 70 km3 of stagnant water (Witus and others, Reference Witus2014), so the storage capacity exists in the paleo-subglacial topography. However, because the onset of deposition for Subunit 1A could be as recent as ~200 cal yr BP (Witus and others, Reference Witus2014), by which time most of inner PIB was already deglaciated, we believe that much of the sediment was stored in subglacial basins behind the modern grounding line and that sorting in a distributed subglacial system occurred farther up the catchment.

Our hypothesis illustrates that sediment stored in basins can be expelled due to a change in hydraulic gradient and transported at low velocities. The hydraulic gradient can be steepened by a combination of an increase in basal traction, thinning and surface slope steepening. The increase in basal traction can be achieved through grounding line retreat across the sediment/bedrock boundary, which could cause a steepening of the surface slope. Glacier thinning could occur through retreat. These conditions enable the expulsion of sediment at low velocities, which provides an explanation for the widespread distribution of sorted silts with little or no ice-rafted detritus on the Antarctic continental shelf (Prothro and others, Reference Prothro, Simkins, Majewski and Anderson2018). Large volumes of meltwater from subglacial volcanism or subglacial lake drainage are not needed, although both are known to have contributed to subglacial, sediment-laden meltwater discharge events in the Ross Sea (Simkins and others, Reference Simkins2017).

The discrete layering, radiocarbon data and 210Pb radioisotope accumulation data in Unit 1 have been used to show that Subunit 1A has an order of magnitude higher deposition rate than Unit 1 as a whole, which has prompted the interpretation that Subunit 1A was deposited in a higher energy drainage event (Witus and others, Reference Witus2014). One possible explanation for the apparent difference in deposition rates is that it is an effect of the fraction of time that sediment was being eroded in each unit. There could have been periods of quiescence during which the basins were filling with sediment rather than being deposited throughout PIB, so the Unit 1 deposition rates during periods of basin erosion were could be comparable to Subunit 1A deposition rates. Furthermore, deposition rates for Subunit 1A were primarily based on 210Pb data, while total deposition rates for Unit 1 were based on radiocarbon ages (Witus and others, Reference Witus2014), which could bias deposition rate interpretations. We also note that although 210Pb deposition rates have been used to infer a Subunit 1A deposition onset time of ~200 cal yr BP (Witus and others, Reference Witus2014), the actual date could have been earlier if there was a period of non-deposition. This phenomenon, known as the ‘Sadler effect’, is seen globally in a variety of depositional environments and is responsible for a perceived increase in deposition rates over time (Sadler, Reference Sadler1981; Schumer and Jerolmack, Reference Schumer and Jerolmack2009). It is also possible that observed differences in deposition rates can be attributed to changes in which basins were eroded as the grounding line retreated. As the grounding line and steepened hydraulic gradient moved inward across different basins, the location of erosion would also have moved inward. This means that Subunit 1A was sourced from basins farther inland than basins that output Subunit 1B. Because the sediment for Subunit 1A was likely stored in different basins than Subunit 1B, the filling and erosion timeline and magnitude may have varied. Therefore, order of magnitude differences in apparent deposition rates could be observed without exceeding a water velocity of ~10 cm s−1.

PIB and Marguerite Bay have strikingly similar morphology and geology and have both undergone large-scale retreat during the Holocene (Heroy and Anderson, Reference Heroy and Anderson2007; Anderson and Fretwell, Reference Anderson and Fretwell2008; Cofaigh and others, Reference Cofaigh2014). Our mechanism offers an explanation for the sorted mud drape in this region and suggests that a similar hydrologic sorting and deposition process could be used to explain sediment sequences in Marguerite Bay.

Together, these findings suggest that basal geology and morphology may exert a strong control on the local configuration of the subglacial water system during ice-sheet retreat. This raises the possibility that similar subglacial hydrologic systems and conditions could have occupied the bedrock basins of the paleo-Pine Island and Marguerite ice streams during multiple glaciations and that similar conditions and processes may be at play in the grounded bedrock portions of contemporary Thwaites and Pine Island Glaciers.

Conclusion

PIB has geomorphic evidence of a large-scale subglacial drainage system and dramatic ice sheet retreat during the late Holocene, but it is difficult to reconcile high-energy drainage events with the fine, sorted sedimentary units present in PIB. We provide a mechanism for the prior sorting and deposition at water flow velocities that need not exceed ~10 cm s−1, where upstream slow-moving water sorts sediment into subglacial basins that are eroded by a steepening of the hydraulic gradient during grounding line retreat. We conclude that this mechanism differs from the outburst drainage that shaped the Labyrinth, and that subglacial volcanism or large-scale subglacial lake drainage are not needed to generate the late Holocene sediment deposits and morphology of PIB. A similar mechanism may be responsible for features observed in Marguerite Bay, suggesting that similar subglacial hydrologic conditions and transitions may occur across the ice sheet during retreat.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the attendees of the 2019 IGS Symposium on Erosion and Sedimentation for their insightful and encouraging discussions. We'd also like to thank Richard Alley and an anonymous reviewer for their helpful reviews. DMS, EJM and TTC were partially supported by a grant from the NASA Cryospheric Sciences Program.