In the last decade, three-dimensional digitization, also known as 3D scanning, has become one of the principal tools of documentation and investigation of archaeological artifacts and features, particularly in the context of efforts to preserve and promote cultural heritage (Wachowiak and Karas Reference Wachowiak and Karas2009). Many projects working in the Maya area—including Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, Atlas Epigráfico de Peten, Text Database and Dictionary of Classic Mayan, and Google Arts and Culture—have adopted various tools and techniques of 3D documentation to generate large online collections of portable artifacts, digitized monuments, and even whole buildings (Coughenour and Cooper Reference Coughenour and Cooper2017; B. Fash Reference Fash and Pillsbury2012; Gronemeyer et al. Reference Gronemeyer, Prager and Wagner2015; Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine2013). Nevertheless, these emergent digital collections account for only a fraction of the known corpus of Classic Maya inscriptions.

This article presents the results of a project aimed at adding the inscriptions of the archaeological site of Dzibanche (Figure 1) to the corpus of texts recorded and investigated with 3D digitization. The hieroglyphic stairs of Dzibanche are one of the most important Classic Maya monuments. Ever since the discovery of 26 carved stairway blocks mostly embedded into the steps leading to Building 13 or the “Temple of the Captives” (Figure 2) during the 1993–1994 field seasons of the Proyecto Arqueológico Sur de Quintana Roo (Nalda et al. Reference Nalda, Campaña and Lopez1999), epigraphers were aware of its historical significance as a window into a series of events leading to the rise of the Kaanu'l dynasty as the dominant political force in the Maya Lowlands (Martin Reference Martin2020; Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008[2000]; Martin and Velásquez García Reference Martin and García2016). The original publication of the stairs, directed by Enrique Nalda (Reference Nalda2004b), set the standard for the field by combining an extensive discussion of the archaeological context, line drawings, and photographs of the finds (Nalda Reference Nalda and Nalda2004a) with commentaries and analysis by epigraphers (Grube Reference Grube and Nalda2004; Martin Reference Martin and Nalda2004; Velásquez García Reference Velásquez García and Nalda2004).

Figure 1. Location of Dzibanche and other archaeological sites with known ties to the Kaanu'l hegemonic network. Drawing by Alexandre Tokovinine.

Figure 2. Central area of Dzibanche showing the location of the “Temple of the Captives” and stairway blocks. INAH lidar data. Image by Francisco Estrada-Belli.

The stairway blocks of the “Temple of the Captives” were clearly taken from multiple earlier monumental programs and placed out of order, which presents a formidable challenge in terms of reconstructing the original narratives and their respective chronologies. Many additional fragments of inscribed monuments, portable artifacts, and molded stucco fragments were recovered during the subsequent field seasons of 2004–2009 at Dzibanche (Nalda and Balanzario Reference Nalda and Balanzario2004, Reference Nalda and Balanzario2006, Reference Nalda and Balanzario2007, Reference Nalda and Balanzario2009), necessitating an effort to document and analyze the new data and to reevaluate prior interpretations in light of the latest findings.

Methods of the present study

The new documentation of Dzibanche monuments relied on 3D scanning complemented by photogrammetry and high-resolution digital photography. The smartSCAN Duo system (GmbH Reference GmbH2008, Reference GmbH2009) was used for 3D scanning. Its modular architecture makes it possible to increase XY resolution and accuracy at the expense of the size of each scan and, consequently, the time needed to document an artifact. Based on prior experience of using this scanner (Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine2013; Tokovinine and Estrada-Belli Reference Tokovinine and Estrada-Belli2017), the setup with the XY resolution of 0.18 mm and accuracy of 0.04 mm (scan area diagonal of 30 cm) was deemed the best fit for the size of the carved details on the monuments, with the exception of the Early Classic stela fragment that was documented with the resolution of 0.055 mm and accuracy of 0.012 mm (scan area diagonal of 9 cm). The OPTOCAT 2010 software was used to process the data. Further cleaning of finished 3D models was undertaken using the Geomagic Wrap program (3D Systems, Inc. 2017). Finished models were visualized in Meshlab (Cignoni et al. Reference Cignoni, Callieri, Corsini, Dellepiane, Ganovelli, Ranzuglia, Scarano, De Chiara and Erra2008) using raking light and a radiance-scaling filter to enhance the visibility of carved details (Vergne et al. Reference Vergne, Pacanowski, Barla, Granier and Schlick2010).

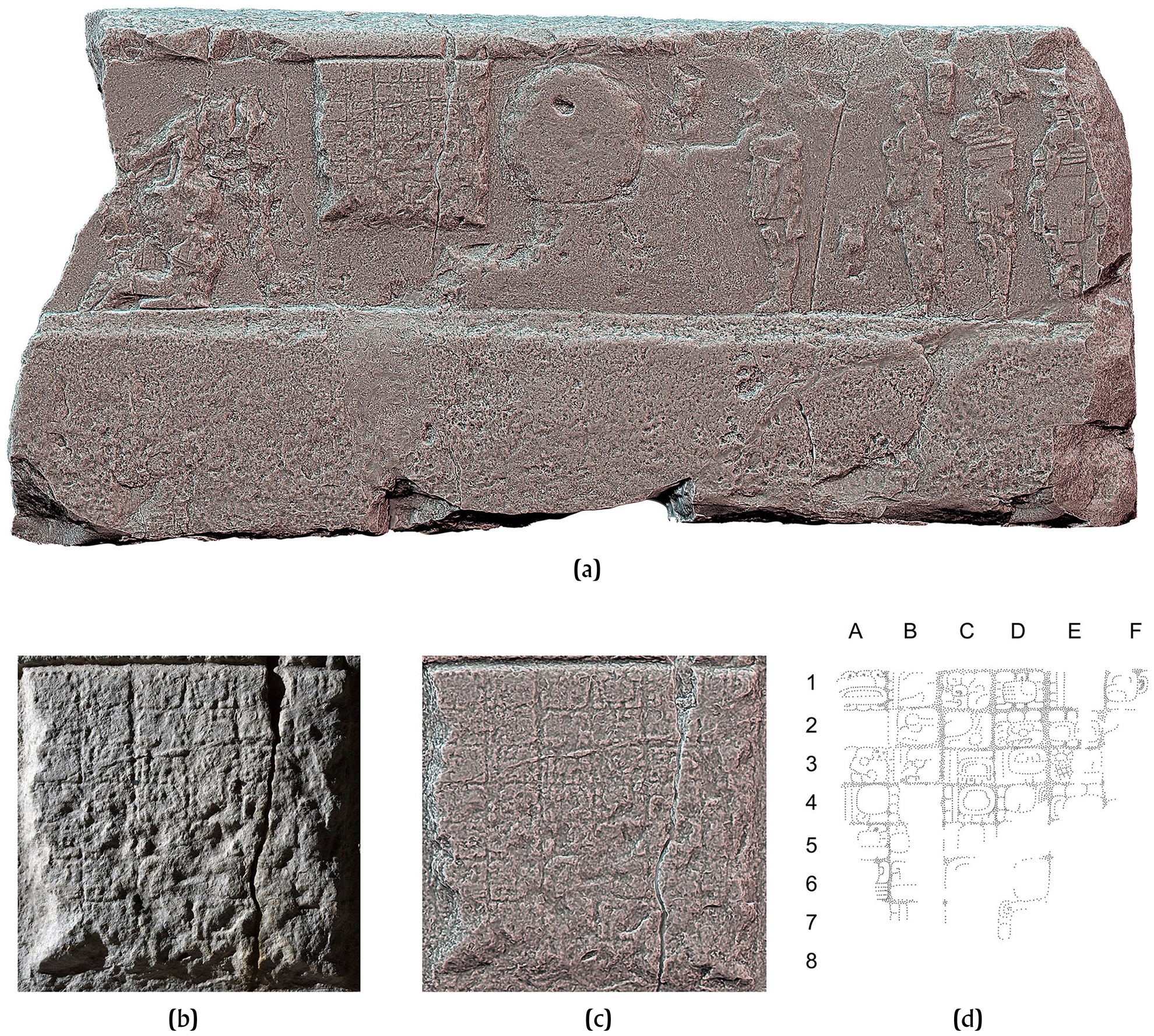

Each monument was additionally captured with a Nikon D800 digital camera and raking light from a synchronized remote flash for sharper contrast. The main goal of this secondary documentation was to record any detail smaller than the primary 0.18 mm XY resolution of the 3D scanner. In practice, 3D scans proved to be more useful for epigraphic analysis, particularly with the radiance-scaling filter (Figure 3). Additionally, in contrast to scan-based orthoimages, photographs suffered from distortions caused by the lens and by the close distance between the monuments and the camera.

Figure 3. A comparison of (a) raking-light photography, (b) grayscale, and (c) radiance-scaling visualization of the 3D model of Monument 16. Photograph by Dmitri Beliaev. Visualizations by Alexandre Tokovinine.

The structure-from-motion photogrammetry dataset was intended to complement the scans where time constraints did not permit scanning plain areas of the monuments. Data collection for photogrammetry was much faster when compared to 3D scanning. Photogrammetry-based 3D models also represented color better than the 3D scans (Figure 4a–b). However, photogrammetry data were characterized by substantially lower accuracy than scans of similar resolution by the smartSCAN duo Scan so that, when compared to scan-based 3D models (Figure 4a and 4c), photogrammety-based 3D models appeared blurred (Figure 4b and 4d). The issue could be addressed by drastically increasing the photogrammetry resolution via lens or camera sensor, but the resultant datasets would have been too large to process. Color fidelity was less important because no paint was preserved on the monuments. All photogrammetry-based 3D models of the stairway blocks exhibited deviations from actual dimensions in the range of 1–3 mm and, therefore, could not be treated as faithful representations.

Figure 4. Detail of the stucco frieze of Structure E2 illustrating outcomes of different documentation strategies: (a) color visualization of the scan-based model; (b) color visualization of the photogrammetry model; (c) radiance-scaling visualization of the scan-based model; (d) radiance-scaling visualization of the photogrammetry model. Visualizations by Alexandre Tokovinine.

The images for photogrammetry were captured with the Sony A7R III 40 MP digital. In addition to a full-resolution Stanford Triangle Format mesh, a smaller Wavefront .obj mesh with separate texture layers was created for each scanned monument to be shared online.

The stairways of Dzibanche: How many monumental programs?

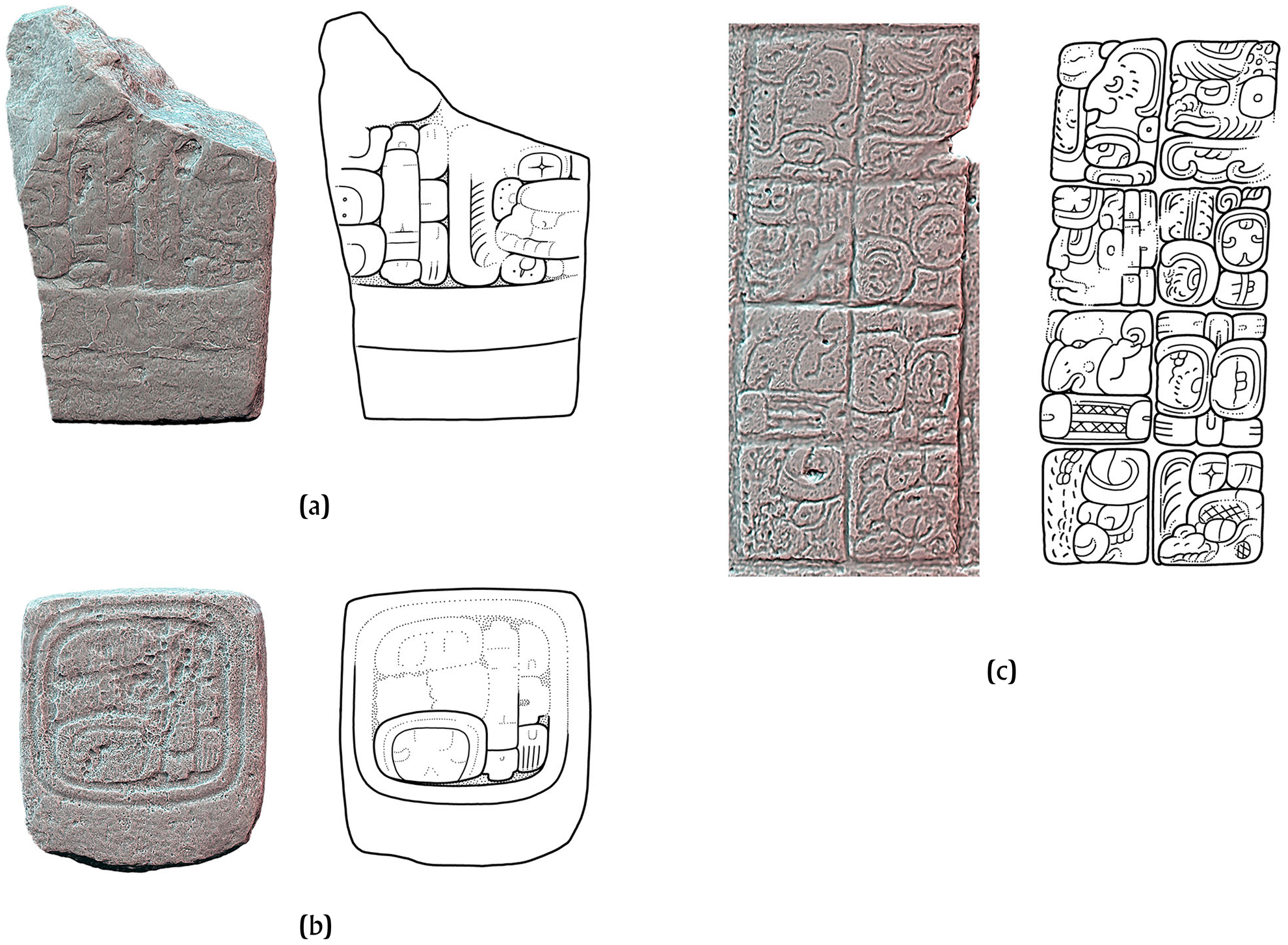

Previous surveys of Dzibanche stairways identified at least two distinct programs of monuments subsequently reset into later structures with loss of the original order (Nalda Reference Nalda and Nalda2004a; Velásquez García Reference Velásquez García and Nalda2004, Reference Velásquez García2005). The configuration of the monuments conformed to the two common approaches to hieroglyphic stairways by ancient Maya carvers: blocks that take most of the volume of a step or blocks that form a veneer on the front side of a step and are partially embedded into the construction fill. The visible sections of all Dzibanche blocks are about 30 cm tall (Figure 5), consistent with their function as monumental stairway steps.

Figure 5. Multiple stairway programs at Dzibanche illustrated by distinct blocks shown at the same scale (top and front views): (a) Monument 5; (b) Monument 2; (c) Monument 4; (d) Fragment 6; (e) Fragment 1; (f) Fragment 4; (g) Fragment 5; (h) Fragment 7; (i) Fragment 2. Visualizations by Alexandre Tokovinine.

Each stairway program at Dzibanche was characterized by blocks of distinct size and shape, as well as strikingly different patterns with respect to the placement and organization of carved images and hieroglyphic inscriptions. The first program was represented by massive blocks, approximately square in cross-section, leaving almost no space at the bottom for the construction fill (Figure 5a), with images of bound captives accompanied by hieroglyphic captions. Yuknoom Ch'een I (Grube Reference Grube and Nalda2004; Velásquez García Reference Velásquez García and Nalda2004) was the main protagonist of the narrative on the blocks. The second program (Monuments 2, 4, 16, and 19) corresponded to narrower stairway blocks that were not designed to fill the full depth of the steps and that were provided with plain sections at the bottom to be embedded into the construction fill (Figure 5b–c). Monument 2 of the second program was recarved from an earlier panel or a bench as indicated by elements of the original design and at least three round cartouches with single glyph blocks (Figure 5b). The imagery and texts on the second program referenced ballgame (Figure 5c) and the main protagonist was identified as Yax Yopaat (Velásquez García Reference Velásquez García and Nalda2004). The main text on Monument 2 refers to the completion of the seventh katun on 7 Ajaw 3 Kankin, 9.7.0.0.0, December 5, a.d. 573 (Velásquez García Reference Velásquez García and Nalda2004:97, 99). Contrary to Velásquez's assertion (Reference Velásquez García and Nalda2004:98), there is no indication in Monument 4's dimensions, carving layout, or style (Figure 5c) that it belonged to a different set of hieroglyphic steps.

At least seven miscellaneous fragments of stairway blocks have been recovered since the published survey. Fragment 3 belongs to a block of the first monumental program. Fragment 6 (Figure 5d) conforms to the parameters of the second monumental program. However, Fragments 1, 4, 5, and 7 share a different set of dimensions and reveal what may be interpreted as remains of a third hieroglyphic stairway (Figure 5e–h). These blocks are similar to the second program in that they are relatively thin and intended as front surfaces of the steps. However, the new blocks are smaller, roughly square, and with less space for fill embedding at the bottom. The inscriptions on the blocks were carved in round cartouches with up to four glyph blocks in each. Cartouches could span more than a single block. This organization resembles a subset of the blocks of the hieroglyphic stairways at the nearby site of El Resbalón (Carrasco Vargas and Boucher Le Landais Reference Carrasco Vargas and Le Landais1987). Some seventh-century hieroglyphic stairways also share this format (Helmke and Awe Reference Helmke and Awe2016). No date is visible on the recovered fragments. An incomplete name associated with the Kaanu'l royal title on Fragment 4 (Figures 5f, 8a) may be tentatively read as yu-bi-?li K'INICH. The name does not appear on the codex-style dynastic lists (Martin Reference Martin, Kerr and Kerr1997). The only similar name on the list is that of Ruler 2 (Tayel Chan K'inich), but the name on Fragment 4 is clearly not the same. Given that the royal title on Fragment 4 lacks the k'uhul (“divine/holy”) epithet, we can assume that he was one of the junior members of the royal house who either never reached the high-king status or acquired a different accession name.

Yet another recovered fragment (Fragment 2; Figure 5i) is visibly distinct from the blocks of the three stairways. It is similar in depth to the blocks of the second and the third stairways, but it lacks the round cartouche, and the hieroglyphs are much smaller and carved in a more three-dimensional style than those of the other monumental program. The implication is that there used to be at least four hieroglyphic stairways at Dzibanche. It is apparent that most of the third stairway and nearly all of the fourth stairway remain to be discovered.

Dating the hieroglyphic stairways

Until now, the chronology of the first and the earliest hieroglyphic stairway detailing multiple conquest and capture events has remained partially unresolved. The inscription featured no Long Count anchors. The sequential numbers of conquest events and the protagonist's name provided the only chronological controls for the 52-year Calendar Round dates. Velásquez García (Reference Velásquez García and Nalda2004) proposed the range of a.d. 484–518 for the conquest events. The latest reconstruction of the Kaanu'l dynastic chronology by Martin (Reference Martin2017) placed the reign of Ruler 10, Yuknoom Ch'een I, in the early fifth century and raised the possibility that the dates on the hieroglyphic stairway could be reexamined in favor of an earlier Calendar Round cycle.

Martin's chronology (Reference Martin2017) suggested that Yuknoom Ch'een I reigned between a.d. 402 and 415, because the accession of his successor on the Calendar Round of 11 Caban 10 Ceh was reconstructed as 8.18.19.12.17 (December 13, a.d. 415). However, that reconstruction implied that Ruler 11's tenure lasted until a.d. 464. Ruler 10's reign, on the other hand, ended up compressed into only 13 years despite as many as 16 military campaigns detailed in the inscription on the stairway. As proposed by Vepretskii (Reference Vepretskii2018), one solution is to reconsider the date of Ruler 11's accession in light of the fact that the scribes on the dynastic vases frequently failed to distinguish between the logograms CHAK of the Ceh month and YAX of the Yax month (Martin Reference Martin, Kerr and Kerr1997:853). Assuming a Calendar Round of 11 Caban 10 Yax, one may reconstruct the date of Ruler 11's accession as 9.1.0.2.17 (October 24, a.d. 455). This modification expands Ruler 10's reign to a.d. 402–455 to potentially accommodate the entire sequence of conquests on the first hieroglyphic stairway.

A reexamination of the inscriptions using 3D scans offers additional chronological clues. The damaged Calendar Round on Monument 18 (Figure 6a) corresponds to the attack against the city of Yax K'ahk’ Jol, whose “fifth captive” epithet implies that the event happened early in Yuknoom Ch'een I's reign. The preserved 1 Kankin part of the date indicates that the Tzolkin day could be Edznab, Akbal, Lamat, or Ben (Velásquez García Reference Velásquez García and Nalda2004:94). The visible circle in the corner of the 3D model of the sign favors its identification as Lamat. The coefficient is damaged beyond recognition, but there is only enough space for a number between one and five. Of all possible combinations, two Calendar Round dates fall appropriately early in the reign of Yuknoom Ch'een I: 3 Lamat 1 Kankin (8.18.19.14.8, January 13, a.d. 416) and 2 Lamat 1 Kankin (8.19.11.17.8, January 10, a.d. 428).

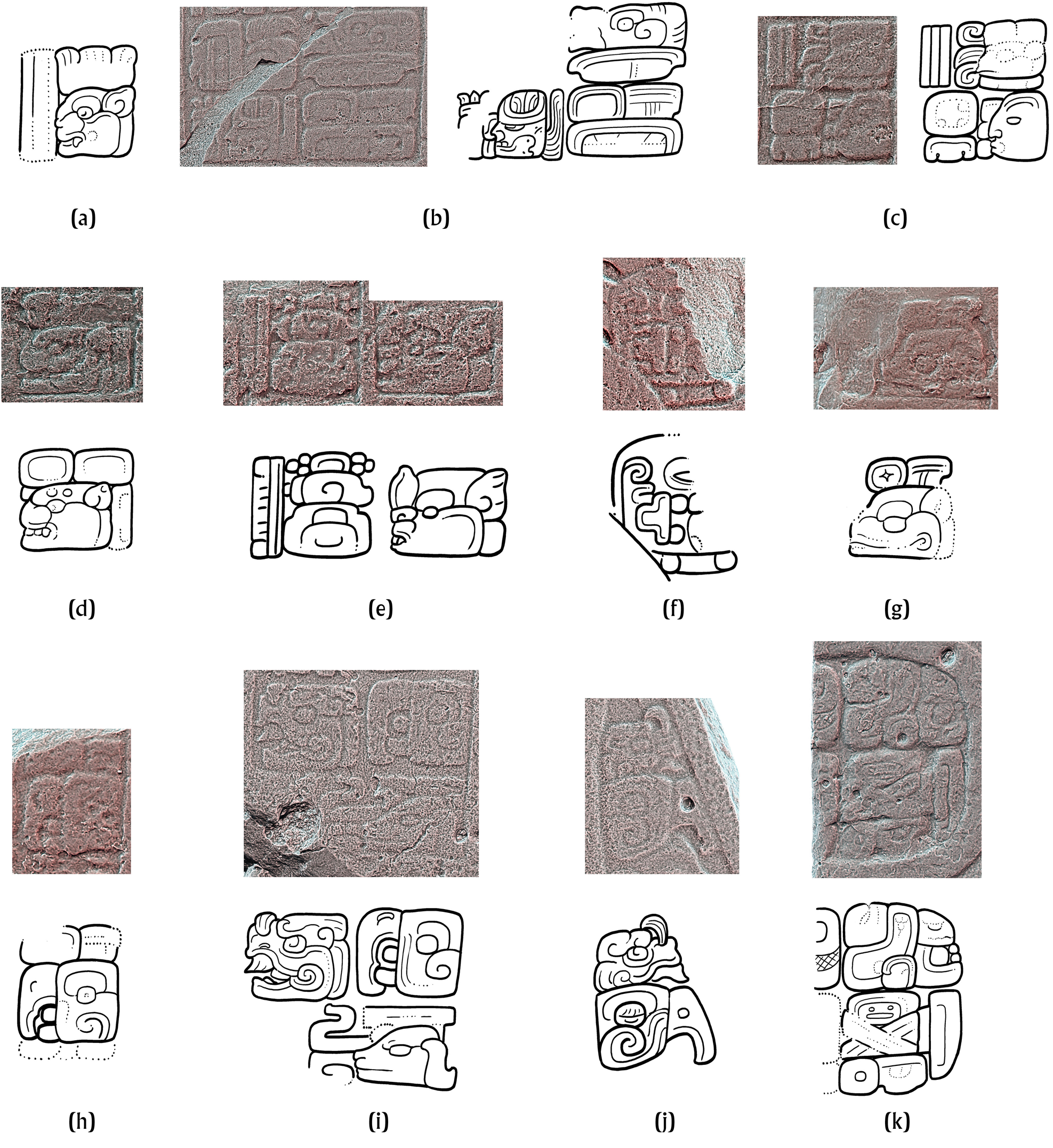

Figure 6. Revising the chronology of Dzibanche Monuments: (a) detail of Monument 18; (b) detail of Monument 15; (c) detail of Monument 22; (d) detail of Monument 11; (e) detail of Monument 4; (f) detail of Monument 19. Visualizations and drawings by Alexandre Tokovinine.

The Calendar Round on Monument 15 was previously interpreted as 10 Men 8 Xul or 10 Ahau 8 Xul (Velásquez García Reference Velásquez García and Nalda2004:93). However, a visualization of the 3D scan of the Tzolkin day is more consistent with a snake head of the day Chicchan (Figure 6b). A combination of 10 Chicchan and 8 Xul corresponds to the Long Count date of 9.0.9.14.5 (August 5, a.d. 445), which falls outside Martin's reconstruction of Ruler 10's reign but fits the proposed a.d. 402–455 chronology. On the other hand, the 3D scan confirmed that the Calendar Round date on Monument 22 (Figure 6c; same date as on Monument 13) was 5 Chicchan 3 Yaxkin (Velásquez García Reference Velásquez García and Nalda2004:96) and could correspond to 9.0.2.13.15 (August 19, a.d. 438).

The caption on Monument 11 mentions the sixteenth and last captive of Yuknoom Ch'een I and should correspond to the later part of his reign. The Calendar Round date is eroded (Figure 6d), but the external contour on the Tzolkin part is only consistent with an Ahau day sign. The damaged Haab month does not readily correspond to any month name. One possible interpretation is that it is a HAAB logogram, and the inscription was meant to state “[on the day] 6 Ajaw [in the] eighteen[th] year [of the katun].” The Calendar Rounds of 6 Ahau 8 Yax (9.0.17.2.0, October 22, a.d. 452) and 6 Ahau 3 Sek (9.0.17.15.0, July 9, a.d. 453) would be the best reconstructions.

An alternative interpretation is suggested by the unusual way of recording the Calendar Round 7 Eb 10 Zac (8.19.2.12.12) on Achiotal Stela 1: the Haab month appears as a single SIHOOM (ku/TUUN) grapheme without its color attribute (YAX, CHAK, SAK, IHK’). Taking into account that the date on Monument 11 is the last military campaign, there are two possible Calendar Rounds: 6 Ahau 18 Yax (9.0.7.0.0, November 4, a.d. 442) and 6 Ahau 18 Ceh (9.0.19.5.0, December 11, a.d. 454).

As mentioned previously, the primary chronological anchor for the second stairway is the completion of the seven katuns in a.d. 573 in the text on Monument 2. The Calendar Round on Monument 4 (Figure 6e) was interpreted as 2 Kan 2 Mac (Velásquez García Reference Velásquez García and Nalda2004:98). However, the remaining circular elements to the left of the Kan day sign are too large for a number and likely correspond to a lower section of the syllable ti, spelling the preposition ti, which may occur in this context. Alternatively, the carver used a bead-like allograph of the number one. If the sign is ti, then there is some empty space above Kan where a numeral coefficient with a value between one and five was likely located. Given the date on Monument 2 of the same stairway, at least two Calendar Round combinations seem plausible: 5 Kan 2 Mac (9.6.12.15.4, November 18, a.d. 566) and 4 Kan 2 Mac (9.7.5.0.4, November 15, a.d. 578). Other combinations such as 1 Kan 2 Mac (9.6.8.14.4, November 19, a.d. 562) would result in dates that appear to be too early. The Calendar Round is preceded by an incomplete glyph block that ends in -ya. It could be a spelling for the expression alay (“here”), which is used to mark the principal event in a narrative. The Calendar Round is followed by a block that contains the logogram PAT, which is used to spell a numeral classifier with counts of repeated actions (Beliaev et al. Reference Beliaev, Galeev, Vepretskii, Beliaev and León2016:115–117; Stuart Reference Stuart2005:70). Despite damage to the block, the initial u- and the final -pat suggest that it contained one such count. The next hieroglyphic block begins with a pi- followed by two eroded graphemes. The second character could be -tzi- so that the spelling corresponded to the verbal root pitz (“to play ball”), in line with the imagery of ballplayers on this stairway.

It is worth mentioning that a previously undiscussed fragment of the same monumental program features remains of a large glyph block with a coefficient of 14 (Figure 5d). The size of the characters (full height of the stairway block) implies that it was a significant section of the text, but the coefficient cannot correspond to any Calendar Round linked to a period ending event. If the block was part of a large-font Long Count date, then its only link to the rest of the stairway is that less plausible reconstruction of the Calendar Round on Monument 4 as 1 Kan 2 Mac (9.6.8.14.4, a.d. 562).

Monument 19 contains the main ballgame scene featuring a central protagonist, possibly a Dzibanche ruler, and a large ball in addition to several other players wearing the game gear (Figure 7a). The main text on the monument once contained at least 48 hieroglyphic blocks, but a large portion of it is damaged beyond recognition (Figure 7b–d). The inscription begins with an Initial Series Introductory glyph in Block A1 followed by a Long Count date in Blocks B1–B3. The number nine coefficient is visible in the baktun position in B1. What remains of the glyph contours in Block A4 indicates that it contained a Tzolkin. The following B4 was likely the Haab part of the Calendar Round, but it is too eroded for identification. Block A6 contains remains of Glyph C of the Lunar Series. Therefore, Block B5 should correspond to Glyph D, whereas Blocks B6–B7 should include the rest of the Lunar Series (Glyphs X, B, and A). The predicate of the sentence would have been recorded in the now-missing pair of Blocks A8 and B8. The agent's name likely begins in the following block (C1) and somewhat resembles the YOPAT logogram. The name continues in Block D1 with YUK-no-ma (see Esparza Olguín and Velásquez García Reference Esparza Olguín and García2013) corresponding to yuknoom, a common element of Kaanu'l dynastic names. The next block (C2) contains a grapheme that looks like a serpent head with a wide-open mouth with an eroded element inside. It resembles the usual way of writing the uk'ay kaan nominal phrase of the Kaanu'l ruler, also known as “Scroll Serpent” (Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008[2000]:105). The position of D2 is consistent with an emblem glyph title at the end of the name, and the poorly preserved contours of the glyphs resemble the Kaanu'l emblem glyph.

Figure 7. Monument 19 and its inscription: (a) general view; (b) inscription photograph; (c) inscription visualization with radiance scaling; (d) inscription drawing. Photograph by Dmitry Beliaev. Visualizations and drawing by Alexandre Tokovinine.

The narrative continues in Blocks C3 and D4, which correspond to a Distance Number. There are at least two numbers in Block C3—a coefficient of six or eight on the left and a bar for five above. Therefore, C3 should represent the count of days and months. Block D4 would then be a count of years, but its coefficient is all but gone. The following pair of hieroglyphic blocks, C3 and D4, feature another Calendar Round date. The Tzolkin in C3 has a coefficient of seven, and the Haab in D4 has a discernible number three. The month name itself consists of two elements, and the smaller lower part is preserved well enough to be identified as wa. A Calendar Round of 7 Ajaw 3 Uniiw (7 Ahau 3 Kankin) or 9.7.0.0.0 (December 5, a.d. 573)—the same date as on Monument 2 of the stairway (Figure 5b)—conforms to the preserved elements of Blocks C3 and D4. The sentence after the Calendar Round is completely eroded.

The somewhat legible upper section of the columns E and F provides additional details of the narrative. Block E1 begins with a coefficient of nine and could correspond to a Haab part of a Calendar Round date. It is followed by CHUM-la-ja, chumlaj (“he/she sat,” in an office of some kind) in Block F1. The style of the CHUM logogram is similar to that on Dzibanche Lintel 3, which would be roughly contemporaneous. Block E2 should contain the name of the office into which the protagonist acceded. It is damaged, but the overall contour is consistent with KAL-ma-TE’, kaloomte’, the supreme title in the Classic Maya political hierarchy. K'ahk’ Ti’ Ch'ich’ was the first Kaanu'l ruler who claimed this title upon accession in a.d. 550 (Martin and Beliaev Reference Martin and Beliaev2017:5–6). This interpretation of Block E2 is confounded by the absence of the preposition ti or ta, although it is occasionally omitted in the inscriptions. The rest of the F column is totally gone. The only visible element in Block E3 is the initial ch'a syllable, which could be part of a title ch'ajoom or ch'ajoom ajaw. Block E4 is relatively well preserved and contains the emblem glyph title K'UH-ka-KAN-AJAW, k'uh[ul] Kaanu'l ajaw (“holy Kaanu'l lord”).

There are no dates on the fragments attributed to Hieroglyphic Stairway III. The style of the glyphs fits the late sixth and seventh centuries a.d. A Dzibanche ruler who came to power after the dynastic split of a.d. 636–640 (Martin and Velásquez García Reference Martin and García2016) could be responsible for this stairway, but not necessarily. The only clue about the date of the monument is provided by the ruler's name on Fragment 4 (Figure 8a). Unfortunately, part of the cartouche was carved on the now-missing neighboring block. There are at least three graphemes with simple contours followed by K'INICH. They may be tentatively identified as yu-bi-?li. The identification of yu and bi is relatively secure because few other graphemes share the same elements. Assuming a common yu-[ku] conflation, the spelled word could be the perfect participle yukbil (“shaken”) (see Zender Reference Zender2010). The full name would be yukbil k'inich (“Shaken [is] the Searing [Lord]”). Published drawings of a block of the Hieroglyphic Stairway III at El Resbalón (Carrasco Vargas and Boucher Le Landais Reference Carrasco Vargas and Le Landais1987:Figure 7a; Grube Reference Grube and Nalda2004:Figure 3c) showed a somewhat similar name that included CHAN and K'INICH. However, the redocumentation of the block revealed that it contained an unrelated royal title of unahbnal k'inich (Figure 8b). The overall styles of El Resbalón stairways and Dzibanche Hieroglyphic Stairway III are indeed very similar (compare Figure 5e–h and Figure 8b). The last identified date on El Resbalón stairways is 9.6.15.17.5 (a.d. 589), within Ruler 18's (Yuknoom Ti’ Chan) reign (see Carrasco Vargas and Boucher Le Landais Reference Carrasco Vargas and Le Landais1987:3). As mentioned above, there is no name on the dynastic list that matches Yukbil K'inich on Fragment 4. There are also no outside references. One possible explanation would be that Yukbil K'inich was yet another junior Kaanu'l lord contemporaneous with Rulers 17 and 18.

Figure 8. Identifying the Kaanu'l ruler on Hieroglyphic Stairway III: (a) Fragment 4; (b) Block BX24, Hieroglyphic Stairway III, El Resbalón; (c) detail of the inscribed sherd (GA 5-1/10-391392). Visualizations and drawings by Alexandre Tokovinine.

A gouged-incised vessel fragment found at Dzibanche (GA 5-1/10-391392) contains a fragmentary text (Figure 8c) that includes a parentage statement of the owner (the owner's name is not preserved) that mentions his father: a-xi-sa-ji CHAN-na K'INICH sa-ku wi-WINIK-ki ch'o-ko KAL-ma-TE’ K'UH ka-KAN AJAW, a[j]xisaaj chan k'inich saku[n] winik ch'ok kaloomte’ k'uh[ul] kaan[u'l] ajaw (“Ajxisaaj Chan K'inich, elder brother, youth kaloomte’, holy Kaanu'l lord”). There are two ways to segment this string of titles: (1) sakun winik ch'ok, followed by kaloomte’, followed by k'uh[ul] kaan[u'l] ajaw; (2) sakun winik, followed by ch'ok kaloomte’, followed by k'uh[ul] kaan[u'l] ajaw. The first scenario is supported by the example on the Palenque Palace Tablet (Blocks K7–L11), where sakun winik ch'ok signifies “elder brother” and is accompanied by the “holy Baake'l lord” emblem glyph title referring to a reigning monarch (Sergei Vepretskii, personal communication 2022). However, this interpretation fails to explain why the title of kaloomte’ is cited before and not after the emblem glyph, in an apparent violation of the usual syntactic pattern in which kaloomte’ is the more significant title and occurs after the emblem glyph (see Lacadena García-Gallo Reference Lacadena García-Gallo, Colas, Delvendahl, Kuhnert and Schubart2000). The second scenario assumes that ch'ok functioned as an attribute to kaloomte’: Ajxisaaj Chan K'inich already assumed the position of one of “holy Kaanu'l lords” and was next in line to the high-king office. This interpretation accounts for the syntax: “holy Kaanu'l lord” could be treated as a more significant rank than “youth/aspiring kaloomte’.” Given that there are no references to Ajxisaaj Chan K'inich on codex-style vessels and other texts outside Dzibanche, he apparently never acceded to the kaloomte’ office.

In summary, the revision of the Calendar Round dates on the first hieroglyphic stairway re-arranges the inscriptions in the following chronological order: Monument 18 (a.d. 416 or 428), Monument 22 (a.d. 438), Monument 15 (a.d. 445), and Monument 11 (a.d. 442, 452, 453, or 454). All of these dates fall within the extended chronology of the reign of Yuknoom Ch'een I and conform to the sequential numbers of captives in the narrative. The revised chronology places the dedication of the stairway half a century earlier than previous reconstructions. The reanalysis of the inscriptions on the second stairway proposes two new alternative dates for the Calendar Round on Monument 4. The text on Monument 19 mentions the period-ending date of 9.7.0.0.0 (a.d. 573), although there is also one earlier and one later date in the narrative, and the latter date corresponds to a royal accession. The protagonist of the text carries the Kanuu'l emblem glyph title. His name resembles that of the “Scroll Serpent.” The fragments of the third stairway may be tentatively dated to the late sixth century based on the style of the hieroglyphs.

References to Yukbil K'inich on Hieroglyphic Stairway III and Ajxisaaj Chan K'inich on the ceramic vessel fragment expand the list of Kaanu'l lords, who do not appear in the dynastic sequence on the codex-style ceramic vessels. Yukbil K'inich's lack of “holy” epithet and Ajxisaaj Chan K'inich's “youth kaloomte’” title support Martin's (Reference Martin2017) hypothesis about the organization of the Kaanu'l royal house as a corporate group, where a member was expected to progress through a series of offices culminating with the high kingship. However, the model also implies that there are potentially many more Kaanu'l lords in addition to Yax Yopaat, Yukbil K'inich, and Ajxisaaj Chan K'inich, who were not included in the dynastic list, because it only mentioned the kaloomte’ office holders. This revelation complicates the efforts to reconstruct the history of Kaanu'l and reconcile different kinds of textual sources.

People and places on Dzibanche stairways

One of the biggest challenges in interpreting the epigraphic record at Dzibanche is connecting it to the wider Classic Maya world. Previous attempts to identify known nonlocal place names and personal names in the narratives were not particularly successful. For example, given the above-mentioned connection between Dzibanche and El Resbalón, Velásquez García (Reference Velásquez García and Nalda2004:94) suggested that the captive Yax K'ahk’ Jol mentioned on Monument 18 also appeared in the narratives on El Resbalón hieroglyphic stairways. However, the name cited at El Resbalón is NUM-JOL (Carrasco Vargas and Boucher Le Landais Reference Carrasco Vargas and Le Landais1987:Figure 4) and has nothing to do with the captive at Dzibanche. On the other hand, the name of the local protagonist of El Resbalón narratives combines the logogram BAHLAM with an idiosyncratic grapheme that looks like a piece of basketry (Carrasco Vargas and Boucher Le Landais Reference Carrasco Vargas and Le Landais1987:Figure 2). The only comparable sign used elsewhere is a logogram representing an unfinished basket that may be read as XAN (Prager and Wagner Reference Prager and Wagner2016). In fact, Prager and Wagner (Reference Prager and Wagner2016: Figure 10a) suggested that it was the same grapheme. The text on Dzibanche Monument 13 (Velásquez García Reference Velásquez García and Nalda2004:Figure 14) mentions the capture of a certain Aj-?Xan Bahlam in a.d. 438 (Figure 9a). That looks like a name of someone from El Resbalón. The very same date is also cited on Monument 22, where it is associated with a capture of someone named K'uk’ ?Lak (Figure 9b). K'uk’ Lak is provided with an emblem glyph title. Its toponym consists of the syllables si-ha-ni followed by a damaged logogram. The Colonial-period place name associated with the area of Bacalar near Dzibanche and El Resbalón was (in the original orthography) <Ziancaan> (Roys Reference Roys1957:159). Therefore, it is possible to suggest—albeit very tentatively—that the military campaign in a.d. 438 mentioned on Monuments 13 and 22 targeted the sites in the immediate vicinity of Dzibanche.

Figure 9. Places and people on Dzibanche monuments: (a) detail of Monument 13; (b) detail of Monument 22; (c) detail of Monument 11; (d) detail of Monument 7; (e) detail of Monument 7; (f) detail of Monument 7; (g) detail of Monument 10; (h) detail of Monument 10; (i) detail of Monument 17; (j) detail of Monument 17; (k) detail of Fragment 7. Visualizations and drawings by Alexandre Tokovinine.

Figure 10. Plaza Pom miniature stela: (a) visualization with radiance scaling; (b) drawing. Visualization and drawing by Alexandre Tokovinine.

Other names and place names associated with the captives on the first Dzibanche stairway may not be securely associated with known royal families or sites. The implication is that the narrative deals mostly with local and rather obscure geography. The name of the captive on Monument 11 (Figure 9c) resembles those of Rio Azul rulers (Beliaev Reference Beliaev2017), but the revised chronology no longer conforms to this interpretation. One of the two captives on Monument 7 is identified as BALAM-li-AJAW, Bahlamaal ajaw, “lord of Bahlamaal” (Figure 9d). The other captive (Figure 9e) is labeled as AJ-t'o-lo SUUTZ’, aj-t'olo[l] suutz’ (“the person from T'olol Suutz’”). The same title could be interpreted as a personal name (the agentive prefix as a marker of male gender), but the name on the back of the captive is not T'olol Suutz’ (Figure 9f), confirming that the main text refers to a place name. The way of referring to captives by their places of origin is common for members of secondary elites (Stuart and Houston Reference Stuart and Houston1994:19–21). The emblem glyphs of the captives on Monument 10AB include an unidentified place name with a logogram resembling a snake head (Figure 9g) and the toponym spelled MO’-la, Mo'ol (Figure 9h). One more place name potentially occurs in the text on Monument 17. The main text mentions the capture of Xook Mo’ (Figure 9i), and the same name appears on the back of the captive (Figure 9j). Previous interpretations assumed that a glyph block was missing in the lower-left section of the main text (Velásquez García Reference Velásquez García and Nalda2004:94). However, the 3D model indicates that there is no space for another hieroglyphic block (Figure 9i). Therefore, the name of the captive is followed directly by a toponym spelled K'AHK’-chi-NAAH for K'ahk’ Chi[h] Naah or K'ahk’ Naah Chi[h]. The toponym could be a way of referring to the captive's hometown. It could also be a rare mention of the location of the battle where Xook Mo’ was captured.

Despite the fact that only a fraction of what was apparently a third hieroglyphic stairway at Dzibanche has been recovered so far, it provides important information about the external contacts of the Kaanu'l dynasty. Fragment 1 (Figure 5e) mentions a military engagement that happened at Dzibanche (Martin and Velásquez García Reference Martin and García2016:29). The main cartouche on Fragment 7 (Figure 5h, 9k) is incomplete, but it contained two statements, the first beginning with a verb ending in -aj (the same element may also be part of the HUL logogram spelling huli, “she/he arrived at”). The first sentence ends with a toponym spelled chi-KA’-a that likely corresponds to Chih Ka’, a place of major significance in many Classic-period narratives, particularly for the Kaanu'l dynasty (Grube Reference Grube and Nalda2004:129–131; Stuart Reference Stuart2014; Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine and Díaz2020:259–261). The texts on El Resbalón stairways mentioned above also contain multiple references to Chih Ka’ as the seat of a kaloomte’ overlord named Num Jol (Carrasco Vargas and Boucher Le Landais Reference Carrasco Vargas and Le Landais1987:Figure 4), although the chronological placement of Num Jol's reign is unclear. Nevertheless, the implication is that Chih Ka’ was located not far from Dzibanche and El Resbalón. This hypothesis is additionally supported by the remaining text on Fragment 2 (Figure 5i), which refers to a capture of someone from or at Chih Ka’. The second toponym, Wiinte’ Naah, is firmly linked to a place or a building in the ancient city of Teotihuacan where, according to several Classic-period narratives, affiliated ancient Maya rulers received insignia of high office (Estrada-Belli et al. Reference Estrada-Belli, Tokovinine, Foley, Hurst, Ware, Stuart and Grube2009; W. Fash et al. Reference Fash, Tokovinine, Fash, Fash and Luján2009). Although there are no other texts describing travels or events at Wiinte’ Naah involving Kaanu'l rulers, their occasional title of “those of Chih Ka’, those of Wiinte’ Naah” indicated that the dynasty saw Chih Ka’ and Wiinte’ Naah as foundational for its claims of legitimacy and regional political authority (Prager Reference Prager2004; Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine and Díaz2020:264–266). It appears that the narrative of the third hieroglyphic stairway at Dzibanche contained a discussion of these relationships and connections.

An early Kaanu'l lord on a stela fragment from Plaza Pom

A miniature stela fragment recovered in 2009 from the collapse debris of Building 1 in Plaza Pom (Southern Palace, southwestern corner of the quadrant EP-101) at Dzibanche provides a window into the history of the dynasty before the conquests detailed on the hieroglyphic stairways. It also offers a glimpse of the religious life at the site.

The monument corresponds to an upper-left section of a stela carved on only one side (Figure 10). The remaining section features the head of a ruler facing right, toward a small column of glyphs. A serpent body frames the scene. A large speech or breath volute may be seen near the mouth of the ruler. Given that the upper-right part is broken off, it is possible that the original composition of the monument featured two rulers facing each other across a column of hieroglyphs. That said, the serpentine frame body appears to be twisting immediately to the right of the glyph column. If this is indeed the case and not an artifact of poor preservation, then there would be no space for another human figure besides the protagonist. The style of the image and the inscription is solidly Early Classic. The diagnostic Early Classic details include large earflares, a headdress held with straps tied under the chin, the protagonist's breath represented as a large jewel, and graphemes with irregular external contours (see Lacadena García-Gallo Reference Lacadena García-Gallo1995; Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1950).

The text in the main column consists of only three blocks (Figure 10), and there is no indication that there was more text. It begins with a Tzolkin day of 13 Ik followed by tz'a-pa-ja CHAK-WAY, tz'a[h]paj chak way[aab] (“Chak Wayaab was planted/set into the ground”). In the description of the New Year rituals associated with the year bearer of Muluc, Diego de Landa describes the erection of the statue of <Chac u Uayeyab> and its placement in the east (Tozzer Reference Tozzer1941:144). The term wayaab in the Classic-period texts seems to be the counterpart of Landa's <uayeyab> (Beliaev Reference Beliaev, Behrens, Grube, Prager, Sachse, Teufel and Wagner2004). Because of a shift in the year-bearer Tzolkin days between the Classic period and Landa's account, the day 13 Ik may fall on a New Year. Other Classic Maya monuments celebrated New Year rituals, although they were not named wayaab (Martin et al. Reference Martin, Tokovinine, Treffel, Fialko, Arroyo, Salinas and Ajú Álvarez2017; Stuart Reference Stuart2004). If this stela is a New Year monument, as its name apparently suggests, then the Haab date of 0 Pohp was omitted as self-evident. The combination of 13 Ik and 0 Pop occurred in a.d. 270, 322, 374, 426, 478, and 530. The fourth- and fifth-century dates are consistent with the style of the monument.

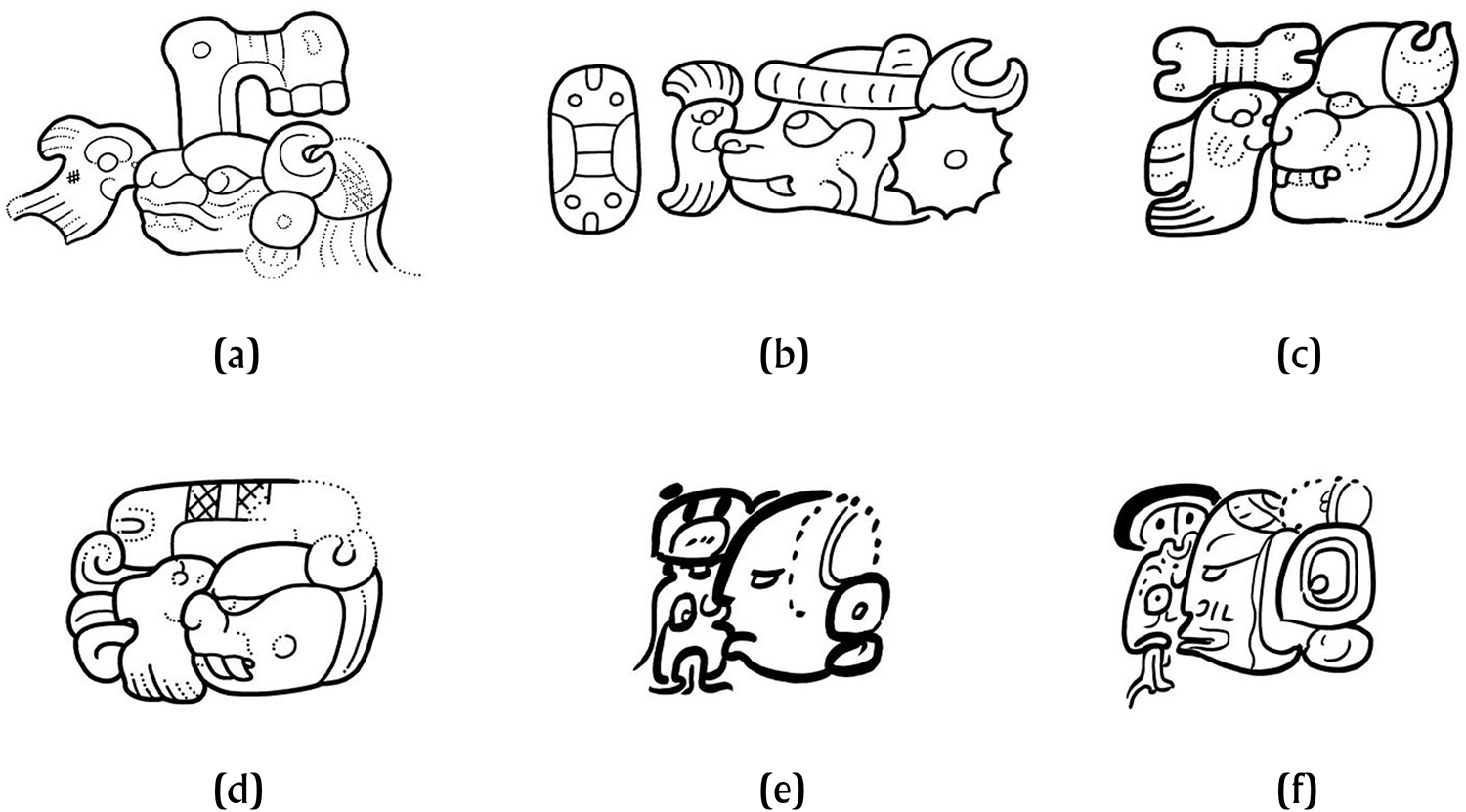

The protagonist's headdress is essentially a combination of two sets of hieroglyphs that spell two halves of his name or that refer to the supernatural entity impersonated on the occasion or even the name of the local royal crown. The bulk of the headdress consists of a XOOK shark head with a ne syllable infixed in the ear area (Figure 10). The top of the XOOK head features wrinkles and several additional elements resembling one or more graphemes: a container or bundle of some sort, three volutes, and deer antlers. The volutes resemble the to/TOK sign, and the antlers function as a XUKUB logogram in the script, but it is equally plausible that they could be elements of a single grapheme.

The inscription on an Early Classic carved travertine bowl discovered in Tomb P2B-5 at Santa Rita Corozal (Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase2005; Helmke Reference Helmke2020:Figure 8) names the owner of the vessel as K'ahk’ Neh Chih Xook—“Fire-tail(ed) Deer Shark.” It is tempting to see the names on the Santa Rita Corozal vessel and the Plaza Pom stela as equivalent: the to/TOK volutes could be an idiosyncratic local allograph of K'AHK’, and the antlers could belong to an allograph of the chi syllable, so the whole combination would be K'AHK’-ne-chi-XOOK for k'ahk’ ne[h] chi[h] xook. However, reading the volutes as K'AHK’ would require a substantial stretch of the imagination. Moreover, the interpretation would not explain the strange object between the volutes and the XOOK head. One alternative is to consider the antlers and the objects as an early variant of the SI'P logogram as described by Grube (Reference Grube2012). During the Late Classic period, the simplest version of the grapheme looks like an overturned jar marked as something woven with antlers or volutes (Figure 11a). More detailed variants show the same element on top of the old Deer God head (Figure 11b) or as his earflare (Figure 11c). Si'p is a divine patron of hunting and wild animals, but he also sports a wasp nest on his head (Figure 11d). The object on the Plaza Pom stela looks more like a wasp nest than the corresponding element of the Late Classic, which may be explained by the analogical graphemic standardization that affected the whole corpus during that period (Lacadena García-Gallo Reference Lacadena García-Gallo1995). Therefore, it is possible that the headdress of the Plaza Pom protagonist is a combination of to/TOK-ne-SI'P-XOOK or SI'P-ne-XOOK for tok ne[h] si'p xook or si'p ne[h] xook: “cloud/mist-tail(ed) Si'p shark” or “Si'p-tail(ed) shark.” Si'p is frequently depicted on codex-style pottery, where he usually emerges from the mouth of the chihchan (“deer snake”) earthquake-making wahy entity of the Kaanu'l royal family (Grube and Nahm Reference Grube, Nahm, Kerr and Kerr1994; Helmke and Nielsen Reference Helmke and Nielsen2009). It would make sense that the crown of Dzibanche rulers was a Si'p shark.

Figure 11. Decoding the crown on the Plaza Pom stela: (a) SI'P logogram on a codex-style vessel (after Grube Reference Grube2012:Figure 13); (b) SI'P logogram on an incised Early Classic tripod (after Grube Reference Grube2012:Figure 2b); (c) SI'P logogram on Yaxchilan Lintel 1 (after Grube Reference Grube2012:Figure 3); (d) Si'p deity with a wasp nest emerging from the mouth of Chihchan wahy of Kaanu'l lords, detail of a codex-style vessel (after Robicsek et al. Reference Robicsek, Hales and Coe1981:27, 44. Drawings by Alexandre Tokovinine.

The second set of hieroglyphs in the protagonist's headdress (Figure 12a) almost certainly spells his own name. It consists of a mandible variant of CHAK (Stuart Reference Stuart1987) and a logogram that represents the head of a mammal eating a fish. This pair of graphemes occurs on several Early Classic monuments and portable objects (Figure 12b–c). It is common in the royal names at El Zotz, where it is usually followed by the gloss ahk (“turtle”) (Houston Reference Houston2008). One example of these glyphs on an unprovenanced stone sphere presently on display in the Cozumel Museum (Mayer Reference Mayer2001) offers a potential phonetic clue: a syllable ya is inserted between CHAK and the fish-eating mammal (Figure 12d). Dmitri Beliaev and Albert Davletshin suggested in 2012 that the reading of the fish-eating mammal glyph was YAK, yak (“fox”) with cognates in Cholti, Qeqchi, Quiche, Pocomchi, Pocomam, Tzutujil, and Ixil (Wichmann and Brown Reference Wichmann and Brown2000).

Figure 12. The name of the protagonist of the Plaza Pom stela: (a) close-up of CHAK-?YAK-? on the Plaza Pom stela; (b) CHAK-?YAK on an Early Classic jade celt (after Coe and Kerr Reference Coe and Kerr1998:46–47); (c) CHAK-?YAK on Bejucal Stela 2; (d) CHAK-ya-?YAK on an unprovenanced stone sphere; (e) variant 1 of Ruler 8's name on a codex-style vessel (after Robicsek et al. Reference Robicsek, Hales and Coe1981:99); (f) variant 2 of Ruler 8's name on a codex-style vessel (after Kerr and Kerr Reference Kerr and Kerr1990:217)

The glyph on the miniature stela appears to be a conflation of ?YAK with another hieroglyph revealed behind the mammal head—a combination of a scroll and vegetal elements or hair. It does not look like a conflation with an AHK logogram of the El Zotz version of the name, but there is another case that explains this peculiar form. The name of Ruler 8 of the Kaanu'l dynastic list features the CHAK logogram and then the fish in the same position as in ?YAK, but it is combined with a glyph that looks like the head of the maize god (Figure 12e) or a wind deity (Figure 12f). Martin (Reference Martin, Kerr and Kerr1997:858) proposed that the fish and the maize deity were a conflation of two signs, in which the deity head covered half of another grapheme. The right half of the deity head in Ruler 8's name looks very similar to the visible part of the logogram apparently occluded by ?YAK in the name on the miniature stela. Therefore, the spelling on the miniature stela may correspond to Ruler 8's name. The scribes of the codex-style pottery and the stela carvers only relied on different conflation strategies.

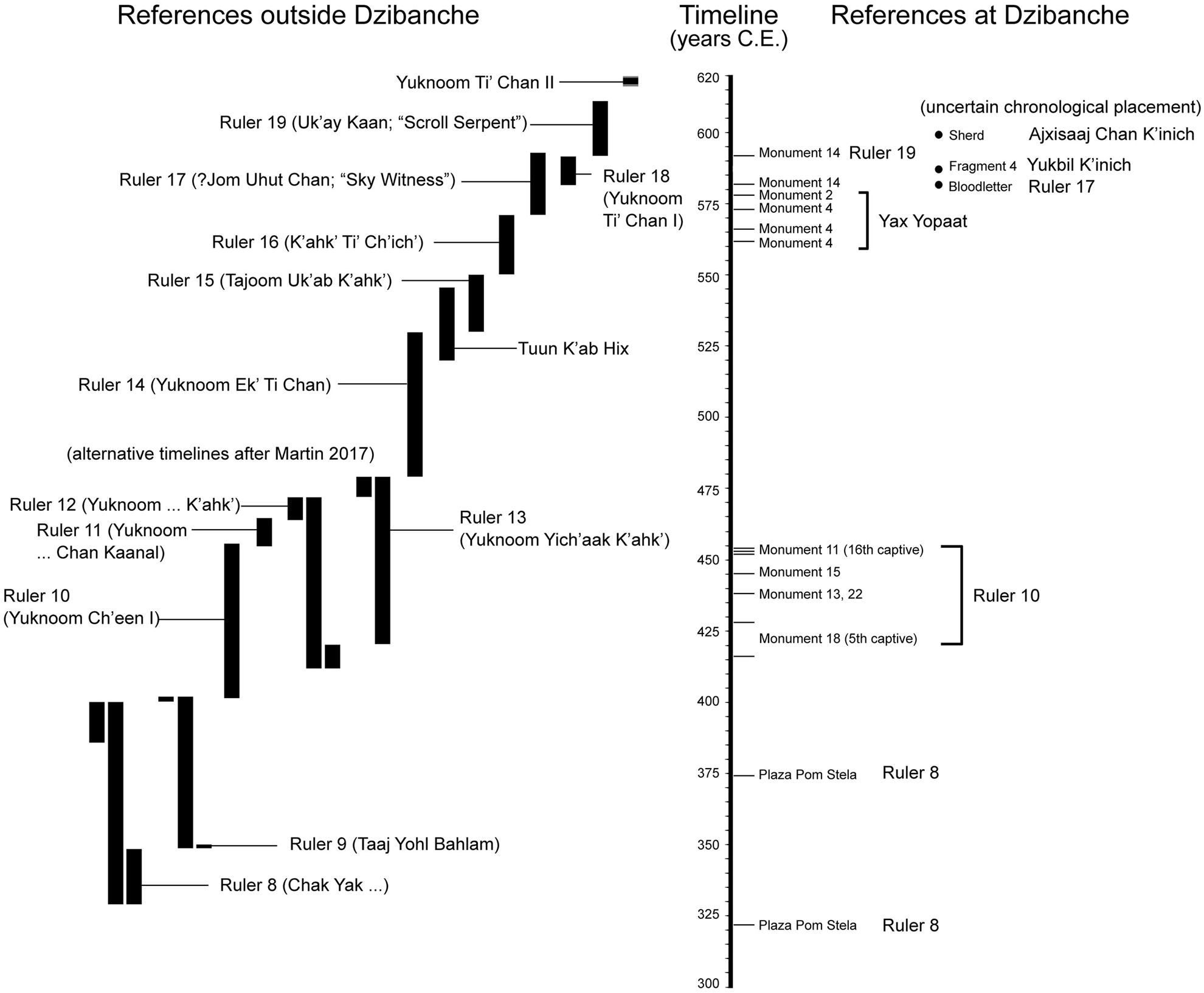

Martin's revision of the Kaanu'l chronology (Reference Martin2017) places Ruler 8's accession either in a.d. 381, 329, or 277, and Ruler 9's accession in either a.d. 400 or 348 (Figure 13). The proposed New Year years are a.d. 270, 322, and 374. If we assume that the miniature stela was dedicated by Ruler 8 when he was in power, the only plausible chronology would be Ruler 8's accession in a.d. 329, followed by the stela dedication in a.d. 374, followed by Ruler 9's accession in a.d. 400. However, this reconstruction means a rather unlikely length of Ruler 8's reign (closely matching that of Ajnumsaaj Chan K'inich at Naranjo) and a very short tenure for Ruler 9. The alternative would be to assume that Ruler 8 dedicated the monument in a.d. 322 before his accession in a.d. 329 (or in a.d. 374, before his accession in a.d. 381) or during a prolonged period of corulership with Ruler 9 in a.d. 374 (Figure 13). There is not enough data to choose the most optimal scenario. Preaccession roles and corulership were common among the Kaanu'l lords, to the point of requiring a revision of the dynastic chronology by Martin. Regardless of this uncertainty, one can add another name to the list of Early Classic Kaanu'l rulers who definitely resided and dedicated monuments at Dzibanche.

Figure 13. The Kaanu'l dynastic sequence from outside sources and Dzibanche references. Some rulers are provided with alternative timelines based on the codex-style ceramics’ Calendar Round dates as reconstructed by Martin (Reference Martin2017). Drawing by Alexandre Tokovinine.

Conclusions

The high-resolution 3D documentation of Dzibanche monuments offered significant insights into the history of the site, and it has broader implications for understanding the political trajectory of the Kaanu'l dynasty and its relation to Dzibanche. The first important conclusion of the analysis is that there were at least three and perhaps four hieroglyphic stairways at the site. One or two of the stairways could be produced after the famed dynastic conflict of a.d. 636–640, attesting to Dzibanche's continued role as a regional center. It is equally significant that the discovered fragments represent only a fraction of what the full set of blocks forming Stairways III and IV could be like. Stairway II appears to be also highly incomplete. This is a testament to how much in the history and epigraphy at Dzibanche remains to be discovered.

The study of Dzibanche inscriptions led to several chronological revisions and observations (Figure 13). The proposed reexamination of the chronology of conquests and captures reported on Hieroglyphic Stairway I suggests that the military campaigns took place between a.d. 416 and 454 and corresponded to the revised extent of the reign of Ruler 10, also known as Yuknoom Ch'een I (a.d. 402–455). It is worth mentioning that the presence of events dated only with Tzolkin days implies that they could pertain to larger campaigns anchored in time with full Calendar Round dates. As for the location of conquered places and their rulers, the campaign of a.d. 438 possibly targeted the rulers of El Resbalón and the area of Bacalar. The place names of Bahlamaal, Mo'ol, T'olol Suutz’, and K'ahk’ Chih Naah are not mentioned elsewhere and likely belonged to the political landscape in the vicinity of Dzibanche. In other words, the conquest narrative dealt with the original expansion or consolidation of the core area under Dzibanche's control during the first half of the fifth century a.d. Like the nearby El Resbalón inscriptions, Dzibanche texts mention events at the important place of Chih Ka’, although the context of the references remains unclear. Dzibanche texts also apparently described events in Teotihuacan. It is potentially significant that textual references to Teotihuacan appear to be retrospective and produced in the sixth century.

A closer examination of the 3D scans of Dzibanche Hieroglyphic Stairway II, especially Monument 19, revealed a potential reference to the “Scroll Serpent” (Uk'ay Kaan) member of the Kaanu'l dynasty. Although the only firm date on Monument 19 is the period ending of 9.7.0.0.0 in a.d. 573, the narrative references an earlier event (ruler's birth?) and a later accession to the kaloomte’ office. The new interpretation of the date on Monument 4 suggests three alternative dates: a.d. 562, 566, or 578.

The fragment of an Early Classic miniature stela is the earliest known example of a New Year monument in the Maya area. The name of the protagonist of the image on the stela likely corresponds to that of Ruler 8 of the Kaanu'l dynastic list. Although the dates for the monument and the dates of Ruler 8 are relatively close, the match is not exact, and several scenarios are possible. One scenario assumes a very lengthy reign for Ruler 8 and a very short one for his successor. The other considers periods of corulership between Rulers 7 and 8 and/or 8 and 9. The corulership interpretation conforms to what we are beginning to understand as the inherent aspect of the organization of the Kaanu'l royal house.

The analysis of Dzibanche texts has identified two additional Kaanu'l lords—Yukbil K'inich and Ajxisaaj Chan K'inich—who are not mentioned in the dynastic list on the codex-style vessels. The manner in which Ajxisaaj Chan K'inich's “youth kaloomte’” title was reported as a less significant rank than that of a “holy Kaanu'l lord” provides additional support of Martin's (Reference Martin2017) hypothesis that there were multiple “holy Kaanu'l lords” at the top of the Kaanu'l hegemony, all under the sway of a single kaloomte’. At least one of them was a designated successor to the kaloomte’ office, but that position presumably did not come with its own seat of authority, hence its lower rank in relation to that of a “holy lord.” “Kaanu'l lords” such as Yukbil K'inich formed an even larger group of royal house members aspiring for one of the “holy lordship” seats. It appears that one's genealogy mattered only in terms of broader membership in the Kaanu'l royal house, not in terms of genealogical proximity to any current top-office holder. Given the context, the “elder brother” (sakun winik) title likely marked one's general seniority rather than specific kinship placement in the royal house. Therefore, we can tentatively propose that there were at least five ranks withing the Kaanu'l royal house: (1) Kaanu'l lords, (2) “holy” (k'uhul) Kaanu'l lords, (3) “senior” (sakun winik) lords, (4) kaloomte'-in-waiting (ch'ok kaloomte'), and (5) kaloomte'.

Finally, it is worth emphasizing that the digital 3D database of Dzibanche monuments has applications beyond epigraphy. The detailed record of the carved surfaces will assist future conservation efforts and provide a benchmark to check the stability of the stone monuments over time. The record also creates new opportunities for dissemination of information for research and educational purposes, either in digital (virtual) or physical (3D-printed) form. The applications and implications of this new data set deserve further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This project was authorized by the National Institute of Archaeology and History of Mexico (INAH). We thank the administration and staff of the Regional INAH office in Chetumal, the Dzibanche Archaeological Zone, and the Maya Museum of Cancun for supporting the project and providing access to research and storage spaces. Our appreciation goes to INAH technicians in Chetumal – Miguel Angel Ramírez Gongora, Jorge Antonio Díaz Hernández, Luis Alfonso Moreno Dominguez, Daniel Gerardo Muños Martinez, and Santiago Vizcarra Delgado - who assisted with accessing and documenting the monuments. The University of Alabama provided institutional and financial support (CARSCA grants #364 and 412). Additional funding came from the Rust Family Foundation (grant #22-0667). The University of Alabama Undergraduate student, Andrew Littlejohn, volunteered for the first field season of the project and greatly helped our 3D scanning effort. This manuscript has benefited from comments and observations by many colleagues. We are particularly grateful to Simon Martin, Sergei Vepretskii, Eric Velásquez García, and the anonymous reviewers. We remain solely responsible for any errors or omissions.