Introduction

Many governments invest significant resources to communicate with foreign citizens.Footnote 1 This type of government-sponsored communication, often called “public diplomacy,” represents a prominent component of states’ overall foreign policy today. Their endeavors are intended to shape global affairs through improving the perceptions of their leaders, country, people, and core values and increasing support for specific policies. But can governments actually sway the opinion of foreign citizens with such diplomatic efforts?

The study of public diplomacy has bloomed into a substantial literature: an expanding number of academics, along with the high-level officials engaging in public diplomacy, see international public engagement as crucial to achieving a state’s foreign policy goals (e.g., Hartig Reference Hartig2016; Mor Reference Mor2006; Peterson Reference Peterson2002; Wilson Reference Wilson2008). However, other scholars dismiss diplomatic outreach to public audiences, claiming that it lacks credibility, delivers no tangible benefits, or is merely a performance for the benefit of domestic audiences (Darnton Reference Darnton2020; Edelstein and Krebs Reference Edelstein and Krebs2005; Hoffman Reference Hoffman2002). It is often portrayed as irrelevant to important outcomes in international relations (Cohen Reference Cohen2017).Footnote 2

Despite these competing claims, there is surprisingly little well-identified evidence about the effectiveness of public diplomacy. In this article, we investigate a fundamental but inadequately scrutinized question about a central causal assumption: whether public diplomacy can, indeed, shape foreign public opinion. To bridge the divide between advocates and naysayers, and to understand the influence of strategic transnational communication in modern international relations, it is essential to determine whether public diplomacy actually sways foreign public opinion.

To answer this question, we emphasize the importance of expanding the scope of public diplomacy studies. The broader literature on “soft power” (Nye Reference Nye2008), almost invariably taken as the appropriate framework for understanding public diplomacy, is U.S.-centric in its theoretical exposition. Empirical studies also tend to be based on single countries, most often the U.S., or at most a few cases (Ciftci and Tezcür Reference Ciftci and Tezcür2016; Heng Reference Heng2010; Köse, Özcan, and Karakoç Reference Köse, Özcan and Karakoç2016; Sun Reference Sun2013). This focus on single-country studies and American soft power does not allow us to answer even basic theoretical questions about the general use of public diplomacy. For example, questions about U.S.-China soft-power competition (Gill and Huang Reference Gill and Huang2006; Scott Reference Scott2015; Shambaugh Reference Shambaugh2015; Wang Reference Wang2008) or the influence of “South-South” public diplomacy (Bry Reference Bry2017) cannot be well-addressed empirically without a general understanding of the efficacy of public diplomacy across countries.

We use two extensive datasets to examine the effect of a major and ubiquitous tool of public diplomacy: high-level political leaders’ visits to other countries (d’Hooghe Reference d’Hooghe2015, 147; Wiseman Reference Wiseman, Melissen and Wang2019, 139). We first collected data on the visits of 15 leaders from nine countries to 38 host countries over 11 years. Next, we combined this dataset on leader visits with individual-level data from the Gallup World Poll (GWP), exploiting the fact that a considerable number of the surveys happened to be in progress at the same time as a high-level visit. This provides an opportunity to identify the causal effect of 86 high-level visits on the approval or disapproval of the visiting leader, by comparing 32,456 respondents interviewed either just before or just after the first day of a visit. As long as there is no systematic difference between these two groups other than when they were interviewed, we can estimate the effects without bias.

We find that on average high-level diplomatic visits increase public approval of the visiting leader’s job performance by 2.3 percentage points—a substantively large effect, which is equal to 41% of the average annual change (in absolute terms) in foreign public approval. The effect is particularly large when the public-diplomacy activities are mentioned in the news media. Furthermore, the effect is not fleeting: the increase in approval persists for weeks. These findings are robust to various model specifications and sensitivity tests, for example removing cases in which the visiting leader made a major policy announcement.

Additional exploratory analyses suggest further theoretical insights. Most importantly, we find little evidence that visiting leaders’ ability to shape foreign public opinion merely reflects their states’ more traditional “hard power” (i.e., military) resources. It appears that states can generate soft-power capabilities independent of their hard-power assets, contributing to an ongoing debate over whether soft power is truly a distinct resource. We also find little evidence to suggest that public diplomacy success is contingent on the popularity of the host-country leadership, or that foreign visits significantly increase the host leader’s popularity. This suggests that leaders conduct public diplomacy to pursue their own goals rather than simply to satisfy the incentives of their hosts.

Our findings speak to several important issues in international relations beyond public diplomacy. Transnational communication is seen as increasingly relevant to international power in the “global information age” (Simmons Reference Simmons2011). Establishing that leaders have the ability to shape public opinion abroad (and exploring the conditions under which this is possible) is a foundational step to understanding how and when states achieve their foreign policy goals in this context. More broadly, public support is relevant to a wide range of international goals. For example, public opinion contributes to a state’s policy on international trade (Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2018), foreign aid (Milner and Tingley Reference Milner and Tingley2011), military coalitions (Goldsmith and Horiuchi Reference Goldsmith and Horiuchi2012), and military bases (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Flynn, Machain and Stravers2020; Cooley Reference Cooley2012). As a result, cultivating foreign public goodwill may assist a state in shaping a partner state’s ability to implement a desired policy across a wide range of policy realms.

In what follows, we first underscore high-level visits as an important type of public diplomacy and discuss the mechanisms underlying the visits’ effects. Next, we specify our testable hypotheses about how the visits change public opinion and discuss methodological challenges for testing them. After we introduce our data and methods, we show the results of confirmatory analysis and of further exploratory analysis. Finally, we conclude and discuss avenues for future research.

Public Diplomacy and Public Opinion

The soft-power framework posits that a country can affect outcomes in international relations through attraction, which is contrasted with more widely acknowledged tools for exercising power such as coercion or inducements (Nye Reference Nye1990; Reference Nye2004; Reference Nye2008).Footnote 3 Although Nye (Reference Nye2008) connects public diplomacy and soft power quite closely, there is an important theoretical distinction. Public diplomacy is best understood as a tool for creating soft-power resources, or “currencies” in Nye’s nomenclature (Nye Reference Nye2004). States can then mobilize these resources to support specific outcomes—to exercise soft power—when pursuing particular foreign policy goals aided by positive foreign opinion, such as building a military coalition or achieving a trade agreement.

To increase soft-power resources, many countries draw on a deep toolbox of public-diplomacy activities, including government-sponsored educational exchange programs, state broadcasting outlets, and cultural events. Head-of-government and head-of-state visits are among the most dramatic forms of public diplomacy, and as a result they can generate considerable media coverage and reach wide audiences. A growing number of studies investigate the relationship between leaders’ travels and domestic and international politics by examining which issues they focus on while abroad (Gilmore and Rowling Reference Gilmore and Rowling2018), how their discourse in foreign countries differs from domestic speeches (Friedman, Kampf, and Balmas Reference Friedman, Kampf and Balmas2017), and how much attention their travels receive (Cohen Reference Cohen2016). The existing literature, however, does not convincingly address the central question of whether public diplomacy actually has its intended effects on foreign audiences (Golan and Yang Reference Golan and Yang2013; Graham Reference Graham2014; Hartig Reference Hartig2016; Scott Reference Scott2015).

High-Level Visits as Public Diplomacy

Leaders around the world devote significant amounts of their scarce and valuable time to international travel. Recent U.S. presidents spent up to one third of their time on international trips (Malis and Smith Reference Malis and Smith2019), during which they engaged in extensive public outreach, directly addressing foreign audiences and attending public events in front of TV cameras. For example, when President Trump visited Japan in May 2019, he held a joint press conference with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, enjoyed a traditional Japanese barbecue dinner, presented an award at a sumo tournament, and met Japan’s new Emperor Naruhito.Footnote 4

Although studies of public diplomacy disproportionately focus on the U.S., leaders of other countries also frequently deploy public-diplomacy campaigns. When Indian Prime Minister Modi traveled to France in April 2015, he held a joint press conference with French President Hollande, visited an Airbus facility, attended a reception at the Carrousel du Louvre, and joined Hollande to release a stamp commemorating 50 years of India-French cooperation.Footnote 5 During his trip to Uzbekistan in October 2018, Russian President Putin held a joint press conference with Uzbek President Mirziyoyev, laid flowers at the Monument of Independence and Humanism, and joined Mirziyoyev to launch the site-selection project for the country’s first nuclear power plant.Footnote 6

Public diplomacy is unlikely to be the primary reason leaders travel internationally, as closed-door negotiations with host leaders affect security (Malis and Smith Reference Malis and Smith2021; McManus Reference McManus2018) and economic (Nitsch Reference Nitsch2007) relationships and the timing and destinations of these trips are often driven by domestic factors (Lebovic and Saunders Reference Lebovic and Saunders2016; Ostrander and Rider Reference Ostrander and Rider2018). Still, given the intense constraints on their time, the fact that visiting leaders often spend significant time on public outreach while abroad suggests they believe this type of public diplomacy brings substantial benefits.

There are multiple possible mechanisms underlying these expected benefits. While the primary goal of this study is not to test any particular mechanism, in the next two subsections, we discuss plausible causal pathways to help illustrate how public diplomacy during a high-level visit reaches targeted audiences, and why individuals in those audiences might change their opinions.

We expect that visiting leaders try to influence foreign public opinion through two processes. First, visiting leaders try to increase awareness of themselves and their country among citizens in the host country. Of the many possible tools of public diplomacy, high-level visits are particularly well suited to gain the audience’s attention due to the large amount of media coverage they tend to draw. Second, through conveying positive messages and images, often focused on the relationship with the host country and its leader, visiting leaders attempt to increase the likelihood that the audience will view them (and, by extension, their country) favorably. High-level visits help leaders achieve this by affording them the opportunity to display their shared goals and values with the foreign audience. For example, leaders often express their shared policy goals with national leaders during joint press conferences, and the cultural activities leaders participate in during their visits are likely meant to signal shared values (Sheafer et al. Reference Sheafer, Bloom, Shenhav and Segev2013).

Host Leader Incentives and Media Environments

Both of the pathways described above—increasing awareness and conveying positive messages—are contingent on (1) how the opportunities for public diplomacy are arranged and (2) how much and in what ways the media cover foreign leaders’ visits. Therefore, to better understand the potentially positive effects of high-level visits on foreign public opinion, we should also consider two additional key actors that shape public diplomacy: host leaders and the domestic media.

Host leaders have the power to shape the effect of international public diplomacy because they play an important role in determining the occurrence, timing, and structure of a visit. Regardless of the relationship between the countries, it is highly unlikely that a visit occurs when either the visiting or host leader is opposed. However, neither the host nor the visitor typically has full control over the public diplomacy activities or messages associated with a high-level visit. Rather, arrangements are often the result of prior negotiation, striking a balance between the messaging goals of each country.Footnote 7

In addition to controlling invitations to foreign leaders, hosts can influence public diplomacy efforts through their agenda-setting power over the topics that domestic media focus on. The effect of a high-level visit is essentially the effect that the visit has on the media system and, in turn, on citizens’ consumption of the media coverage. In either market-driven or state-driven media environments, both visiting and host-country leaders try to arrange events and activities to promote specific images that are beneficial for their own country’s objectives.Footnote 8 Host leaders usually have their own domestic incentives to produce publicly visible and positive visits, which may shore up their own domestic support (Malis and Smith Reference Malis and Smith2021; McManus Reference McManus2018).Footnote 9 As invited guests of the administration in power, visiting leaders typically enjoy some level of endorsement from their host, increasing their legitimacy in the eyes of the foreign public. Therefore, in most cases, the host leader’s ability to direct domestic attention assists the visiting leader in their public diplomacy goals.

Given the mutually agreed nature of the visit and the incentives of both leaders, the media coverage of high-level visits tends to convey positive messages and images about the visiting leader. For example, during Trump’s 2019 visit to Japan, all of the national newspapers gave it front-page coverage. Major news media also frequently reported Trump’s activities in their television and radio broadcasts, social media, websites, and even in video advertisements on trains. These Japanese news outlets tended to emphasize the positive relationship between the two nations in catchy headlines, such as “Japan-U.S. Honeymoon, Built with Golf.”Footnote 10 Unsurprisingly, some news media were more critical.Footnote 11 But even these critical articles often included photos and videos associated with Trump’s actual activities, which conveyed positive nonverbal messages.Footnote 12

In summary, our theory predicts that when public diplomacy visits occur, it is likely that the incentives of the visiting and host leaders are reasonably well aligned and news media are likely to provide some coverage of the visit. As a consequence, a visit raises awareness of the visiting leader among citizens of the host country and conveys positive messages about that leader to them.

However, this does not imply that the visiting leader lacks the ability to sometimes buck the host leader’s preferences and convey public-diplomacy messages based on their own state’s interests and goals. For example, high-level visits can also occur in the context of sharp international rivalry. Nevertheless, the public diplomacy activities may still insert the visitor’s rival messaging goals into the host country’s media (Wiseman Reference Wiseman, Melissen and Wang2019). Recent U.S. Presidents, for example, have engaged in extensive previsit negotiations with China over whether joint news conferences would be held during visits to China and, if so, whether Chinese media would broadcast them live and in full.Footnote 13 Chinese leader Hu Jintao carefully crafted his public-diplomacy messages to maximize their influence on local audiences in the U.S. based on regional economic factors (d’Hooghe Reference d’Hooghe2015) and for citizens in different member-states on a tour of the European Union (d’Hooghe Reference d’Hooghe, Jong Lee and Melissen2011). Even among friendly democracies, messaging goals can diverge significantly between the visiting and host leaders. For example, this is seen in Britain’s (van Ham Reference van Ham, Zaharna, Arsenault and Fisher2013) or Canada’s efforts to affect U.S. environmental policies by going “over the head of the US government” to its constituents (Henrikson Reference Henrikson and Melissen2007, 76).

Hypotheses

The context discussed above helps us theorize the likely microfoundations of citizens’ opinion shifts due to a visit. During high-level visits, we expect that media consumers are often exposed to a high volume of messages about the visiting leader, which increases awareness and reduces their ambivalence toward the leader. Additionally, the majority of these messages are often positive as a result of the carefully orchestrated, generally domestic-leader endorsed, public diplomacy events.

This pattern increases the number of “positive” cues that the public receives about foreign leaders. Since the public (rationally) operates with a low level of information about most foreign policy issues and forms its opinion largely based on elite cues (Popkin Reference Popkin1991; Zaller Reference Zaller1992), increasing the number of such positive messages about the leaders should, on average, positively shift the opinion of individuals.Footnote 14 Furthermore, we argue that leaders’ activities during their high-level visits translate into soft-power resources for their country through improving their own image. Existing research suggests that public opinion of a specific foreign country’s leader has a strong effect on perceptions of both that country and its citizens (Balmas Reference Balmas2018), as well as the approval of that country’s policies (Dragojlovic Reference Dragojlovic2013; Golan and Yang Reference Golan and Yang2013). Therefore, the image of a political leader can be a powerful vehicle through which high-level visits are able to increase their country’s soft power. Our first hypothesis is

Hypothesis 1 High-level visits increase favorable perceptions of the visiting leader in the host country.

There are two ways this effect could manifest. First, consistent with the first mechanism discussed above, it is possible that the visits could increase positive attitudes by increasing awareness and moving respondents from indifference toward a positive opinion. Respondents who have little or no knowledge of the visiting leader should be more likely to take a positive view when exposed to the public-diplomacy messages.Footnote 15

Second, an increase in favorable perceptions may be driven by a decrease in unfavorable perceptions. If the public diplomacy campaign is successful in sufficiently increasing the number of positive signals that a respondent receives regarding a leader, they may update their views from a net-negative to a net-positive perception of the leader.

To test these two proposed mechanisms, we put forth the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2.1 High-level visits decrease indifferent perceptions of the visiting leader in the host country.

Hypothesis 2.2 High-level visits decrease unfavorable perceptions of the visiting leader in the host country

Hypotheses 2.1 and 2.2 are not necessarily competing. Rather, they can be complementary: both a decrease in unfavorable perceptions and a decrease in indifference may contribute to the increase in favorable perceptions expected by Hypothesis 1. However, it is also possible that only one is at play. For example, a visit could polarize public opinion, heightening both positive and negative perceptions while decreasing indifference. Alternatively, the main effect on favorability could be driven by shifts in attitudes among respondents who were previously indifferent, with little change in negative attitudes. If this were the case, it would provide evidence for public diplomacy being most effective by raising awareness among respondents with weak views of the visiting leader. Distinguishing between these outcomes affords insights into the mechanisms behind how public diplomacy functions.

Methodological Challenges

In the scholarly literature, the ability of public diplomacy to increase public support among foreign citizens is assumed, but rarely measured. The paucity of empirical research may be in part due to methodological challenges associated with estimating the effects of public diplomacy—and international visits, in particular—on foreign public opinion. The timing and targets of public diplomacy efforts are strategically driven and therefore nonrandom, which makes it difficult to interpret any estimated effects as causal. We are aware of only one study that attempts to estimate the effects of high-level visits on foreign public opinion, but it does so by controlling for a range of observable variables (Goldsmith and Horiuchi Reference Goldsmith and Horiuchi2009). Because leaders’ strategic considerations are difficult to measure, observational studies that adopt this approach are subject to bias due to unmeasured confounding factors.

An alternative approach uses survey experiments, which offer better insights into the causal link between specific messages from foreign leaders and public opinion outcomes. Existing studies find that the effects of foreign leaders’ messages are contingent on the content of the message, as well as feelings toward the leader, familiarity, and nationality (e.g., Agadjanian and Horiuchi Reference Agadjanian and Horiuchi2020; Balmas Reference Balmas2018; Dragojlovic Reference Dragojlovic2015). However, these findings are predicated on the assumption that leaders’ public-diplomacy efforts reach foreign publics in a form that is similar to what respondents experience on the survey. In real-world settings, leaders compete with many other “noises” in their efforts to improve the images of their country and themselves, including other news events and messages from competing domestic elites. If these noises attenuate the effect of public diplomacy in real-world settings, survey experiments could overestimate the effects of policy messages from foreign leaders.

Research Design

To address the above issues of internal or external validity, we leverage a natural experimental situation and estimate causal effects of high-level visits using individual-level opinion polls generated in the real-world environment at the time of high-level visits. We use a dataset of high-level foreign visits by the principal leaders of nine major states, collected explicitly for this study. We combine these data with the most extensive cross-national survey data available, the Gallup World Poll (GWP).

Public Opinion about the Visiting Country

We measure our outcome variable using GWP (version November 23, 2018). The raw data include annual surveys administered in more than 160 countries from 2005 to 2018.Footnote 16 An important advantage of using this database is that the date of interview is recorded for each respondent. Therefore, with a set of reasonable assumptions, we can estimate the causal effect of a time-specific salient event on public attitudes by comparing respondents interviewed just before the event with those interviewed just after.

To estimate the influence of a high-level visit on public opinion, we use the following GWP question: “Do you approve or disapprove of the job performance of the leadership of (the name of a country)?” While respondents likely do not have much (or any) information about foreign leaders’ actual job performance, we assume that they use their overall favorability toward (or “image” of) the leader to answer this question. In the Supplementary Materials we provide further evidence of the close association of respondents’ assessments of a leader’s job performance and their general attitudes toward foreign leaders and the countries they represent.Footnote 17

From 2008 to 2018, Gallup asked this question—with the same format—about the leadership of 32 countries. Questions about the leadership of some major countries, such as the United States, Russia, and China, were included in all of the GWP annual studies. Other countries, such as Japan, the United Kingdom, and India, were included in most years. Several countries (e.g., Brazil, Turkey, and Iran) were included in the survey only in some years and/or in specific regions. In this study, we use questions about the job performance of the leadership of nine major countries—Brazil, Canada, China, Germany, India, Japan, Russia, the U.K., and the U.S. We selected these nine countries primarily based on their standing as a diverse set of major countries in international affairs, but also on the availability of high-level visit data and practical constraints (e.g., language ability) on gathering detailed information about these visits.

High-Level Visit Data

For these nine countries, we collected, cleaned, and standardized numerous quantitative and qualitative data concerning high-level visits by political leaders.Footnote 18 We focused on the most important and visible leader (or leaders) for each country. In most countries, this is the head of government. For China, since power is centered in the head of the Communist Party (i.e., the General Secretary, who usually also holds the ceremonial post of President), we collected visits by Xi Jinping, and his predecessor Hu Jintao. For Russia, we collected visits by both presidents (head of state) and prime ministers (head of government) because Vladimir Putin remained the de facto political leader when he stepped down from the presidency to become Prime Minister (from May 7, 2008 to May 7, 2012).

We identify the cases in which the leader of Country

![]() $ a=\left\{1,2,\dots, 9\right\} $

visited Country

$ a=\left\{1,2,\dots, 9\right\} $

visited Country

![]() $ b $

(

$ b $

(

![]() $ \ne a $

) during the sampling period of a particular year’s GWP (in Country

$ \ne a $

) during the sampling period of a particular year’s GWP (in Country

![]() $ b $

) that included a question about the job performance of the leadership of Country

$ b $

) that included a question about the job performance of the leadership of Country

![]() $ a $

. Therefore, for each of the nine countries, we focused our data collection efforts on the years in which Gallup included the question about the leadership of the corresponding country. For example, since the question about the job performance of the leadership of Brazil was included only in the 2008–2010 GWP studies, we did not collect information about the Brazilian presidents’ travels after 2010.Footnote

19

$ a $

. Therefore, for each of the nine countries, we focused our data collection efforts on the years in which Gallup included the question about the leadership of the corresponding country. For example, since the question about the job performance of the leadership of Brazil was included only in the 2008–2010 GWP studies, we did not collect information about the Brazilian presidents’ travels after 2010.Footnote

19

We selected all GWP respondents in each host country interviewed within a window of 30 days before or after the first day of a high-level visit to that country.Footnote 20 We removed cases in which the total number of respondents interviewed before or after the visit is less than 10. We then carefully checked all the cases using the original sources (Section B of the Supplementary Materials) and other news articles and excluded the visits for which there was no opportunity for public diplomacy activities, such as stopping over for refueling with no high-level meeting, as well as those that involved only a multilateral meeting (e.g., the G20) with no bilateral meeting with the host leader.

There are 86 visits by 15 political leaders from nine countries to 38 foreign countries that met these initial screening criteria. Table 1 shows the number of valid visits for each leader in our sample. Section C in the Supplementary Materials includes tables listing all visits, their dates, and destinations.

Table 1. High-Level Visits: The Number of Valid Cases by Visitors

Note: See Section C of the Supplementary Materails for details.

It is important to acknowledge that our sample of high-level visits is not a representative set of such visits by all leaders around the world during the period of investigation. However, it is highly unlikely that our selection of valid cases is systematically correlated with strategic considerations underlying the high-level visits. More specifically, it is implausible that the location and timing of each visit is systematically associated with the GWP sampling period. For example, the U.S. President’s travel is predicted by domestic politics as well as the trade and security relationship with destination countries (Lebovic and Saunders Reference Lebovic and Saunders2016; Ostrander and Rider Reference Ostrander and Rider2018). The timing of the next GWP survey in the host country should not be part of planning for high-level visits.

Identification Strategy

To estimate the effects, we focus on respondents who were interviewed just before or just after the first day of each visit. The unit of observation is each respondent

![]() $ i $

for each visit

$ i $

for each visit

![]() $ j $

. Our treatment variable is whether respondent

$ j $

. Our treatment variable is whether respondent

![]() $ i $

was interviewed after the first day of a high-level visit

$ i $

was interviewed after the first day of a high-level visit

![]() $ j $

(

$ j $

(

![]() $ {X}_{ij}=1 $

) or before it (

$ {X}_{ij}=1 $

) or before it (

![]() $ {X}_{ij}=0 $

). We exclude respondents who were interviewed on the first day of a visit because we cannot determine their treatment status.

$ {X}_{ij}=0 $

). We exclude respondents who were interviewed on the first day of a visit because we cannot determine their treatment status.

The variable of interest in the GWP survey is categorical (ordinal)—whether a respondent

![]() $ i $

approves of the job performance of the leadership of a visiting country around the time of a specific high-level visit

$ i $

approves of the job performance of the leadership of a visiting country around the time of a specific high-level visit

![]() $ j $

, disapproves of it, or chooses neither.Footnote

21 The third category includes “Don’t know” and “Refused.” Both of these responses indicate unwillingness to choose a position either due to lack of knowledge or due to mixed and contradictory views.Footnote

22 In this case, raising awareness, adding positive information, or both could lead to a change from this third category to another category (specifically, Approve).

$ j $

, disapproves of it, or chooses neither.Footnote

21 The third category includes “Don’t know” and “Refused.” Both of these responses indicate unwillingness to choose a position either due to lack of knowledge or due to mixed and contradictory views.Footnote

22 In this case, raising awareness, adding positive information, or both could lead to a change from this third category to another category (specifically, Approve).

Although this variable is ordinal, we do not run ordered probit (or logit) regression for our analysis because, as we discuss below, it is essential to include visit-specific fixed effects. We would face the well-known incidental parameter problem (Neyman and Scott Reference Neyman and Scott1948) if we added fixed effects to a nonlinear model, including an ordered probit model. We therefore transform this variable into three dichotomous outcome variables: (1) whether a respondent approves of the job performance of a visiting leader, (2) whether a respondent disapproves of it, and (3) whether a respondent neither approves nor disapproves.Footnote 23

There is a deterministic relationship between the treatment variable and the number of days since the first day of a visit

![]() $ j $

for a respondent

$ j $

for a respondent

![]() $ i $

(i.e., a running variable,

$ i $

(i.e., a running variable,

![]() $ {Z}_{ij} $

): if

$ {Z}_{ij} $

): if

![]() $ {Z}_{ij}>0 $

, then

$ {Z}_{ij}>0 $

, then

![]() $ {X}_{ij}=1 $

. If

$ {X}_{ij}=1 $

. If

![]() $ {Z}_{ij}<0 $

, then

$ {Z}_{ij}<0 $

, then

![]() $ {X}_{ij}=0 $

. However, we do not apply a standard regression discontinuity (RD) design because the running variable is categorical.Footnote

24 As we narrow the “bandwidth” to enhance the validity of our causal inference, specifically for a shorter period of

$ {X}_{ij}=0 $

. However, we do not apply a standard regression discontinuity (RD) design because the running variable is categorical.Footnote

24 As we narrow the “bandwidth” to enhance the validity of our causal inference, specifically for a shorter period of

![]() $ k $

days before and after each visit, the running variable takes only k × 2 distinct values. Without using a continuous variable, we are not able to satisfy the crucial assumption of continuity for RD estimation (de la Cuesta and Imai Reference de la Cuesta and Imai2016)

$ k $

days before and after each visit, the running variable takes only k × 2 distinct values. Without using a continuous variable, we are not able to satisfy the crucial assumption of continuity for RD estimation (de la Cuesta and Imai Reference de la Cuesta and Imai2016)

Instead, for each of the outcome variables, we estimate the difference of means between the treatment group (

![]() $ {X}_{ij}=1 $

) and the control group (

$ {X}_{ij}=1 $

) and the control group (

![]() $ {X}_{ij}=0 $

) given a small value of

$ {X}_{ij}=0 $

) given a small value of

![]() $ k $

. Specifically, we estimate the average treatment effect by running an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression with the treatment variable (

$ k $

. Specifically, we estimate the average treatment effect by running an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression with the treatment variable (

![]() $ {X}_{ij} $

) and visit-specific fixed effects. It is critical to include the fixed effects in our model because we need to compare foreign public opinion before and after the first day of a specific high-level visit. For example, to estimate the effect of Barack Obama’s visit to Denmark in December 2009, we should take the difference in the outcome variable between Danish respondents interviewed just before and just after the first day of this visit. An advantage of our data and approach is the ability to pool these visit-specific effects across many visits and estimate the overall treatment effect.

$ {X}_{ij} $

) and visit-specific fixed effects. It is critical to include the fixed effects in our model because we need to compare foreign public opinion before and after the first day of a specific high-level visit. For example, to estimate the effect of Barack Obama’s visit to Denmark in December 2009, we should take the difference in the outcome variable between Danish respondents interviewed just before and just after the first day of this visit. An advantage of our data and approach is the ability to pool these visit-specific effects across many visits and estimate the overall treatment effect.

The length of the bandwidth for the analysis poses a trade-off between causal inference and statistical power. As we decrease the bandwidth, respondents in the control and treatment groups become more similar in terms of the context in which they respond to the questionnaire, although we inevitably reduce the number of observations. The longer the bandwidth, the larger the number of observations but the more likely that information environments could be different for respondents in the control and treatment groups for reasons not associated with the visit. Considering these costs and benefits, we decided to use k = 5 days. This relatively narrow bandwidth errs on the side of ensuring the validity of our causal inference.Footnote 25 The number of observations within this bandwidth, 32,456, is still sufficiently large for statistical analysis.

The key identification assumption is the lack of any systematic difference between respondents in the control group and those in the treatment group. This assumption holds as long as respondents interviewed before or after the first day of a visit can be considered as-if randomly assigned within each visit. There may be some (unexpected) systematic differences between the two groups for any given case. However, when we pool all 86 cases for analysis, it becomes decreasingly plausible that confounding variables systematically affect the differences in the outcome variable between the control and treatment groups.

We test this assumption by examining the balance of basic demographic questions included in the GWP studies.Footnote 26 Figure D.1 in the Supplementary Materials shows that for most variables, we find no statistically significant difference between the treatment and control groups. We later present the results of a robustness test, reestimating the effects with the imbalanced variables as controls. We also conduct a range of additional tests to further scrutinize the causal effects of high-level public diplomacy on mass opinion.

Results

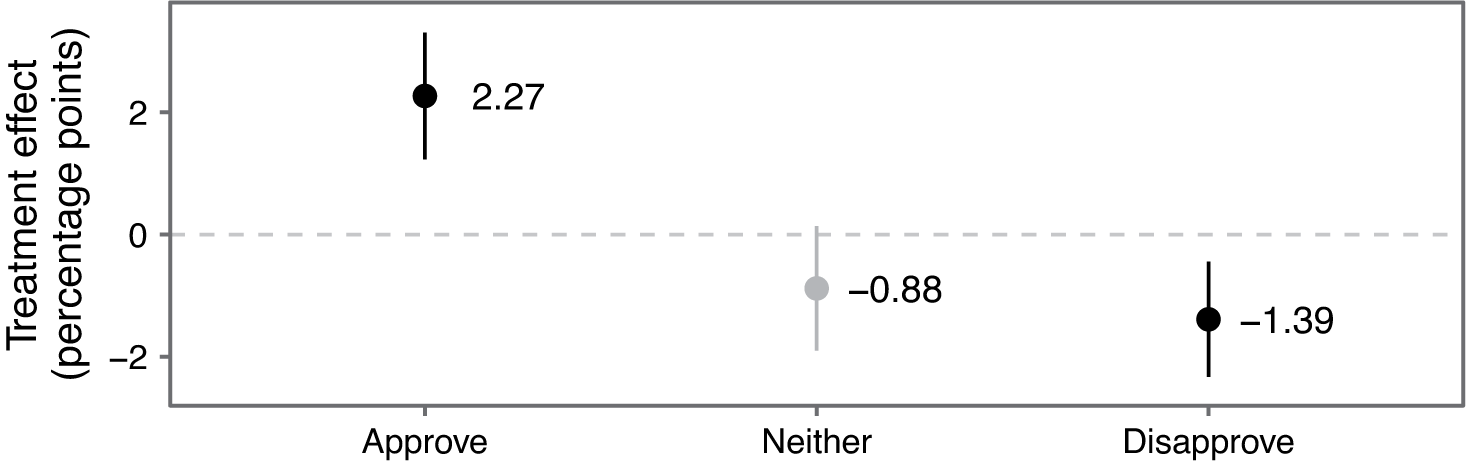

Our analysis shows a substantial increase in approval of the visiting leader: Figure 1 shows a 2.3 percentage point increase in approval, on average, across all the visits in our data (see Table E.1 in the Supplementary Materials for the corresponding regression table). This is clear support for Hypothesis 1. The results are robust to moderate changes in the size of the bandwidth (see Section F in the Supplementary Materials).

Figure 1. OLS Regression Results

Note: Treatment effects using the respondents interviewed within five days before/after the first day of a high-level visit. Vertical bars are 95% confidence intervals. Estimates statistically significant at the 0.05 level are highlighted in black.

Figure 1 also shows a reduction in both indifferent responses and disapproval of the visiting leader: disapproval decreases by 1.4 percentage points and this change is statistically significant. The percentage of respondents selecting neither Approve nor Disapprove decreases by 0.9 points, but the effect is barely insignificant at the 0.05 level. When we use slightly different bandwidths, however, the effect on the percentage of disapproval becomes barely insignificant, whereas the effect on the percentage of neither becomes significant, at the 0.05 level. These results support Hypotheses 2.1 and 2.2, respectively, but overall, empirical support is weaker than for Hypothesis 1.Footnote 27

To assess the substantive magnitude of these effects, we create a benchmark measure of the average fluctuation in foreign public approval/disapproval of leaders. Section H in the Supplementary Analysis details the data and method used to estimate the average annual changes. This analysis shows that the overall average change in the percentage of approval is 5.52 (standard error: 0.46) and the overall average change in the percentage of disapproval is 4.80 (standard error: 0.59). Considering these estimates for annual changes, the estimated effect of a high-level visit is substantial: it is equivalent to 41% and 29% of the average annual change of the approval and disapproval percentage, respectively. It is notable that a single short visit can sway mass opinion to this extent.

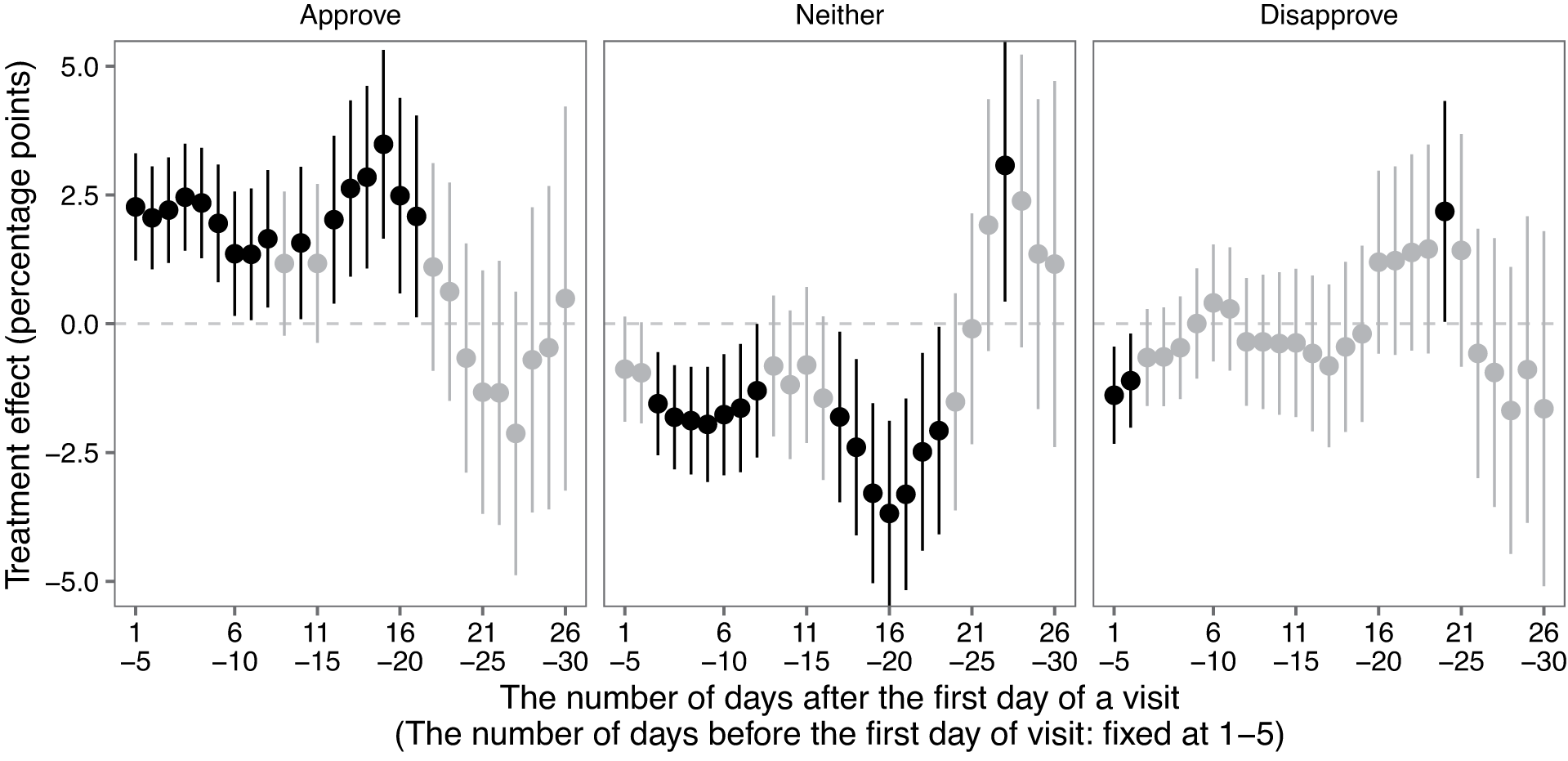

In addition to being substantively large, these effects are not fleeting. To estimate their duration, we use a rolling average based on a 5-day bandwidth, gradually moving farther from the visit’s start. We compare this with the fixed 5-day bandwidth control group immediately prior to the visit.Footnote 28 Figure 2 shows these results for the three response categories. Most notably, the increase in approval for the visiting leader is enduring: this effect appears to last up to about 20 days from the start of the visit. The reduction in ambivalent responses also lasts for roughly 20 days, while the reduction in disapproval is relatively short-lived. If our theoretical conjecture is correct—if indifferent views are more likely to be weakly held and based on low information—then the greater duration of the effect on these views suggests that any lasting influence of a high-level visit operates more through informing the uninformed than through persuading those who previously held a negative view of the visiting country or its leader.

Figure 2. Results of Testing the Effect Duration

Note: We estimate the effects using respondents interviewed within five days before the first day of each visit and respondents interviewed in a rolling five-day period after the visit. Vertical bars are 95% confidence intervals. The estimates that are statistically significant at the 0.05 level are highlighted in black.

The results presented thus far provide evidence that the overall average change in public opinion surrounding a high-level visit is positive, large, and persistent. However, these results may mask important heterogeneity in the treatment effects. Below, we examine some of this variation to establish the robustness of the claim that it is the public diplomacy per se that is creating the average treatment effects. We then turn to a series of exploratory analyses to examine possible extensions of our theory.

Robustness Tests

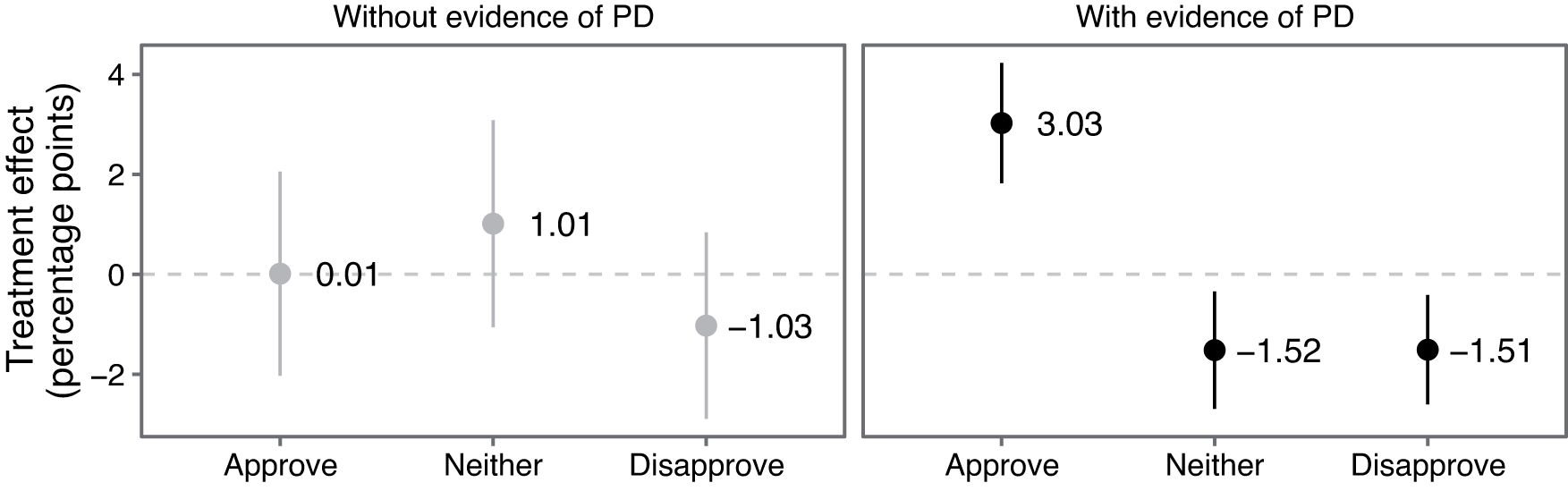

In order for a visiting leader to affect public opinion during a visit, we contend that they must succeed in attracting media coverage of their public outreach events. If this mechanism is correct, then visits should have an effect on public opinion only if the media cover them. In our primary results, we include visits regardless of whether we can confirm any media coverage of public diplomacy activity because we want to keep all cases in which a visiting leader at least had the opportunity to engage in public diplomacyFootnote 29 and because we are not fully certain about the local media coverage of every single case. However, including cases where there was no media coverage of public diplomacy in our estimation could attenuate the effects, thereby introducing bias against finding support for our hypotheses. To understand whether this is the case, we divide all 86 visits into those with and without evidence of media coverage of public diplomacy such as tours of important sites, meetings with citizens, or televised press conferences.Footnote 30 We could not confirm media coverage of public outreach for 17 visits.

The right panel of Figure 3 shows that in cases with evidence of media coverage of public diplomacy, there is a large and significant increase in approval and significant decreases in other responses. In contrast, the left panel shows that there is no effect when there is no evidence of media coverage of public diplomacy. These results suggest that causal mechanisms involving visible public outreach and news media coverage––commonly assumed in the literature and discussed above—help explain the effects we find.

Figure 3. OLS Regression Results by Media Coverage of Public Diplomacy Events

Note: Treatment effects using the respondents interviewed within five days before/after the first day of a high-level visit. Vertical bars are 95% confidence intervals. Estimates statistically significant at the 0.05 level are highlighted in black. “PD” refers to public diplomacy.

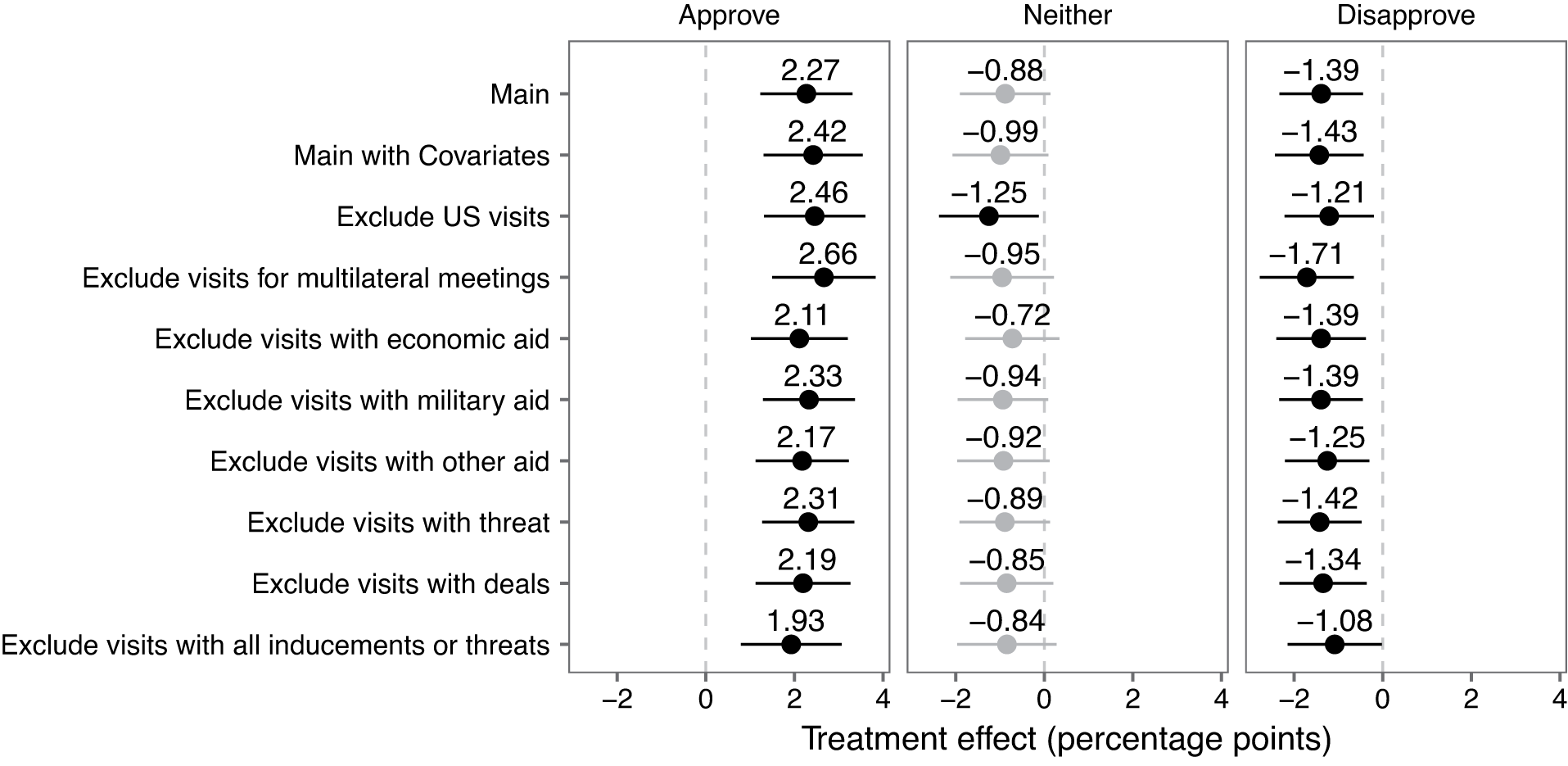

Figure 4 summarizes the results of additional robustness checks.Footnote 31 We first run the regression model with additional controls: the four demographic variables found to be significantly different between the control and treatment groups (see the balance tests in Section D of the Supplementary Materials). The second row of Figure 4 (Main with Covariates) suggests virtually no changes in the treatment effects after including these controls. This is unsurprising because we do not expect that these variables are systematically related to our estimation of the treatment effects.

Figure 4. The Results of Robustness Tests

Note: The figure shows treatment effects using the respondents interviewed within five days before/after the first day of a high-level visit. Horizontal bars are 95% confidence intervals. The estimates that are statistically significant at the 0.05 level are highlighted in black.

The third row of Figure 4 shows the effects after excluding visits by U.S. presidents (Exclude US visits). Given the U.S.-centric nature of the literature, one may anticipate that public diplomacy campaigns are effective only when political leaders of the most powerful nation—the United States—visit foreign countries. But the treatment effects do not change substantially. As further tests, we also undertake sensitivity analysis by sequentially excluding the cases of visits by each of the other eight countries. The results, in Section J of the Supplementary Materials, show that our findings are not sensitive to the exclusion of any one country’s high-level visits.

To examine whether the inclusion of visits with limited public diplomacy activities attenuates the treatment effects reported in Figure 1, we also estimate the effects after excluding 30 visits that had a multilateral meeting in addition to a bilateral meeting between the visiting and host leaders.Footnote 32 The results are presented in the fourth row of Figure 4 (Exclude visits for multilateral meetings). The magnitude of the effects increases from the main results. This is unsurprising because press coverage of multilateral meetings would be diluted among many visiting foreign leaders.

In our estimation of the treatment effects, we assume that citizens of host countries are exposed to public diplomacy campaigns associated with the high-level visits. If there are other major announcements during the visits, the effects could be contaminated, thereby making it more difficult to interpret the effects of public diplomacy per se. To address this potential issue, we reestimate the treatment effects by excluding visits with announcements of military, economic or other types of foreign aid, visits with any sort of threat, or visits with business deals. The details of these inducements or threats are explained in Section K of the Supplemental Materials. The results are presented in the fifth to tenth rows of Figure 4 (Exclude visits with economic aid, Exclude visits with military aid, Exclude visits with other aid, Exclude visits with threat, Exclude visits with deals, and Exclude visits with all inducements or threats). The treatment effects do not change substantially by excluding each type of visit, or all together, so we are confident that our findings are not driven by policy announcements, business deals, or threats that correspond with the visits.Footnote 33

Overall, our robustness tests show that some types of visits may increase or decrease the treatment effects. However, the effects on approval and disapproval remain statistically significant across all tests. The effects on indifferent responses remain negative and barely insignificant or become significant in the case of exclusion of US visits. We thus conclude that our findings, and in particular support for the positive influence of visits—Hypothesis 1—are highly robust to the selection or exclusion of visit cases based on a wide range of considerations. There is compelling evidence that the estimated average effects are attributable to public diplomacy activities.

Exploratory Analysis

Establishing this average treatment effect creates opportunities to greatly improve our understanding of the effects of public diplomacy campaigns. In this section, we undertake several further exploratory analyses. We focus on heterogeneous effects based on power differentials, leader popularity, and leader tenure. While we are not testing any well-elaborated hypotheses, we believe these analyses suggest important theoretical directions for public diplomacy and soft-power research, with broader implications for the study of international relations. For each of the conditional effects, we find that the main result of our analysis—that visiting leaders see an increase in approval—is robust.

Hard Edge to Soft Power?

We first examine the relationship between hard-power resources and the effect of a high-level visit. Evidence that soft-power resources can be built independent of hard-power capabilities supports the contention that power in international relations can be “multifaceted” and “exerted more subtly and gradually” (Baldwin Reference Baldwin2016; Kelley and Simmons Reference Kelley and Simmons2019, 504). However, a high-level visit’s ability to increase soft-power resources might be conditioned by a visiting state’s hard power. This would be the case if citizens of a host country pay more attention to visiting leaders from powerful states—that is, if they view more powerful visitors as better able to bestow benefits, or cause hardship, through their policies. Similarly, host-country citizens may be more receptive to the powerful visitors’ images and messages due to a process of motivated reasoning (Little Reference Little2019). If they understand the potential for substantial inducements or threats from the visiting leader, they may see it as in their interest to take on a shared perspective with the visiting country. This greater attentiveness and openness may be enhanced by greater media attention to more powerful countries (Chang Reference Chang1998).

In short, there may be a hard edge to soft power: even without mentioning explicit threats or inducements, powerful countries may hold advantages in gaining attention and changing public opinion through their public diplomacy campaigns. This possibility poses a fundamental challenge to the soft-power framework. If hard-power capabilities are crucial to building soft-power resources, this supports criticisms that soft power is essentially subordinate to military and economic capabilities (Cohen Reference Cohen2017). Empirically, if this contention is valid, then the effect of a visit would depend on how much more powerful the visiting leader’s country is relative to the host country.

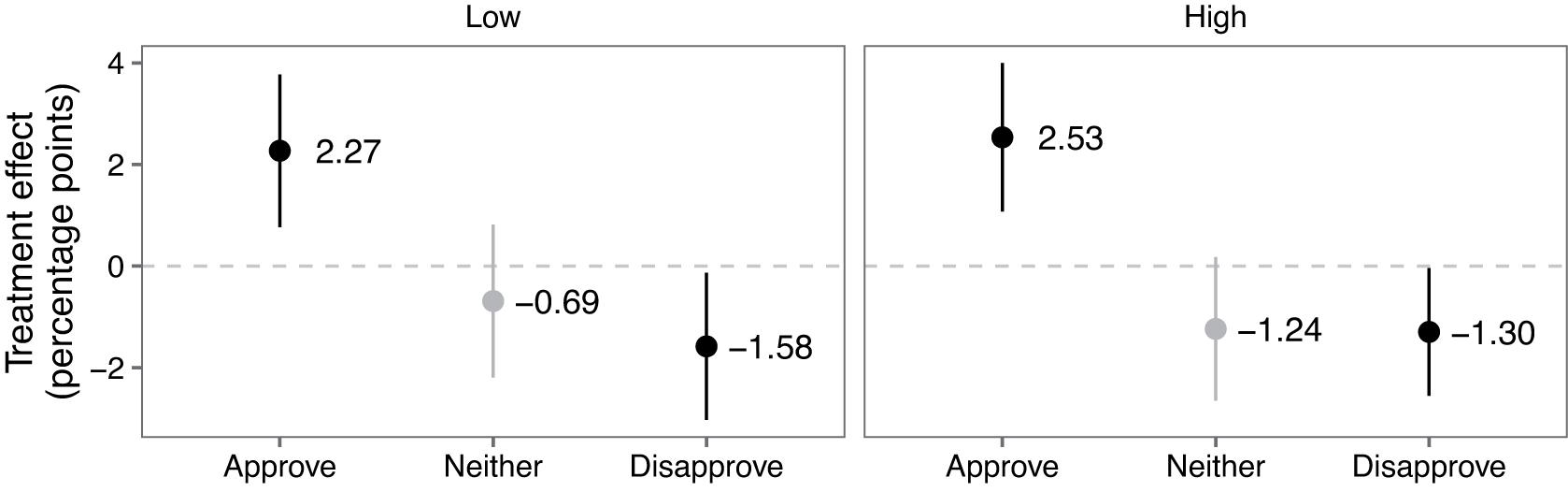

Our analysis shows limited evidence for this. We use the Composite Index of National Capabilities (CINC, Version 5.0) from the Correlates of War project to assess the power ratio between the visiting and host countries (Singer Reference Singer1988). We first split the sample into relatively equal groups, exploiting a natural break in our data: there are no cases with CINC ratios between 6 and 9. For the 45 visits with relatively low ratios (less than 6), the average is 2.9, indicating that the visiting country is on average about three times as powerful as the host. The most imbalanced dyad in this set is Germany visiting Belgium (5.97). For the 40 visits with relatively high ratios (greater than 9), the average is 47.6. The least imbalanced dyad in this group is the U.S. visiting the U.K. (9.08). Figure 5 shows no difference between the treatment effects for these two groups with low and high power ratios.

Figure 5. OLS Regression Results by the Power Ratio of the Visiting Country Relative to the Host Country

Note: The figure shows treatment effects using the respondents interviewed within five days before/after the first day of a high-level visit. Vertical bars are 95% confidence intervals. Estimates statistically significant at the 0.05 level are highlighted in black. To divide the cases into two groups, we use the Composite Index of National Capabilities (CINC) from the Correlates of War project. A ratio greater than 6 is defined as “high.”

However, when we compare cases of extreme imbalance, we do find some supporting evidence for treatment-effect heterogeneity. Specifically, focusing on the highest third of imbalanced cases, with an average ratio of 65.4, we find a substantially larger treatment effect compared with the lower two thirds (see Figure L.2 in Section L of the Supplementary Materials for full results). This includes 27 visits ranging from the U.S. visiting Egypt (14.29 ratio) to China visiting Rwanda (317.56 ratio). With a very high degree of imbalance, there does seem to be a hard edge to soft power, although we emphasize that this assessment of heterogeneous effects cannot firmly establish causation. Still, even visits in the lowest third of power imbalance result in significantly increased approval for visiting leaders. Our best theoretical interpretation from this evidence is that any advantage in public diplomacy due to hard-power capabilities would be limited to vastly more powerful visitors, with capabilities at least a dozen times greater than those of the host.

Soft Power and Foreign Coattails?

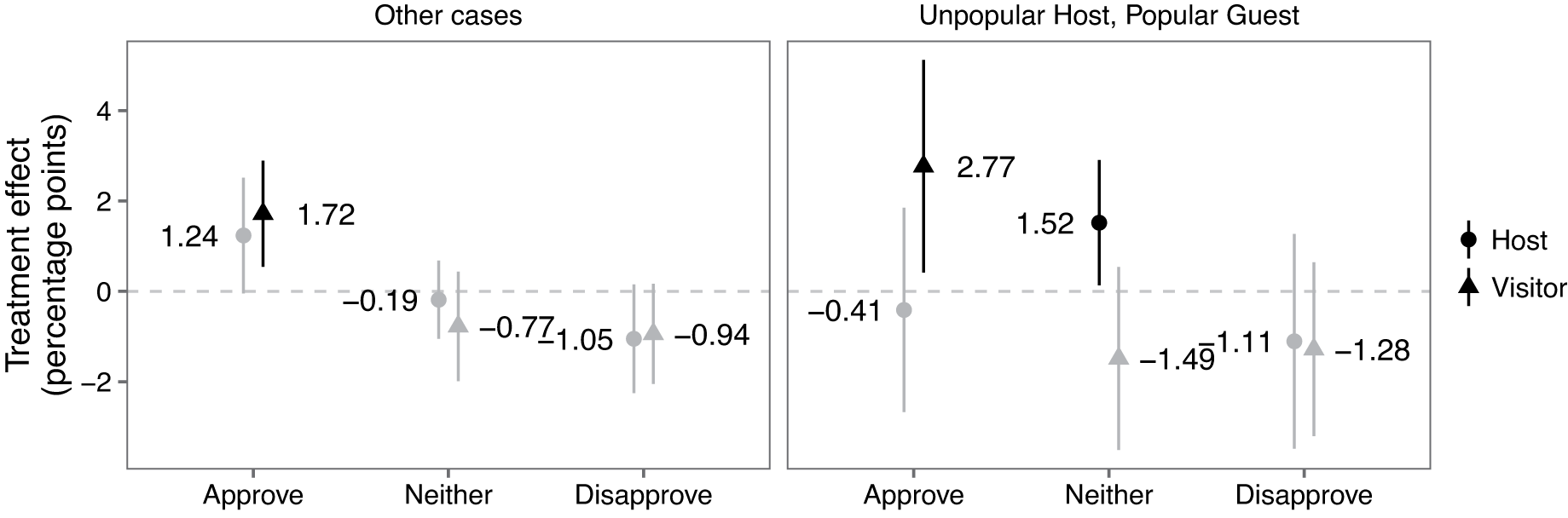

A second category of heterogeneous effects we explore relates to the role of host leaders. Specifically, we might be concerned that high-level visits are primarily directed at benefiting the host leader. To explore this, we examine the subset of cases where we think it is most likely that host leaders’ incentives are driving the effects of the visits. In particular, we consider situations in which a domestically unpopular host-country leader might seek to leverage the high popularity of the visiting leader to advance their own domestic interests, such as bolstering their electoral support or promoting their policy agenda. For example, Barack Obama argued forcefully for the U.K. to remain in the European Union during his 2016 visit prior to the U.K.’s “Brexit” referendum. His host, Prime Minister David Cameron, opposed Brexit but had an approval rating below 40%, while Obama was very popular in the U.K.Footnote 34 If unpopular host-country leaders have these motivations, they could ride the coattails of the popular visitor by using the foreign leader’s visit to gain media exposure, produce more favorable images and messages, and ultimately improve their own popularity.

We assess this possibility by identifying all visits in our dataset for which the previsit job-performance approval of the host is low while the previsit approval of the visiting leader is high.Footnote 35 Specifically, we separate all visits for which the previsit net approval for the host leader is negative (disapproval greater than approval) and the net approval for the visiting leader is positive (approval greater than disapproval). If less-popular hosts are seeking to capitalize on more-popular foreign leaders’ visits, we expect the approval of the host leaders in these cases to increase in response to the visits. Parallel to our main analysis, we use respondents’ answers to the question “Do you approve or disapprove of the job performance of the leadership of (the name of a country)?”

Figure 6 shows the results of this analysis. There is no evidence suggesting that high-level foreign visits translate into a boost in approval for the host leader (circle dots).Footnote 36 At most, there is an increase in indifferent responses about the host leader. We note that host leaders may still believe that they or their policies would see increased popularity by grabbing onto the coattails of a popular foreign visitor—but we find no evidence to support such a belief.

Figure 6. OLS Regression Results by the Job-Performance Approval of the Host-Country and Visiting-Country Leaders

Note: Treatment effects using respondents interviewed within five days before/after the first day of a high-level visit. Vertical bars are 95% confidence intervals. Estimates statistically significant at the 0.05 level are highlighted in black. To divide cases in two groups, we use the difference between the percentage of approval and the percentage of disapproval in the control group. We define a host-country leader or a visiting-country leader as popular if the difference in approval and disapproval is positive.

Dividing our sample in this way also allows us to explore whether the positive effect of public diplomacy for visiting leaders is conditional on the ex ante popularity of the host leader. Yet we find that our main effects on visiting leaders’ approval do not appear to be conditional on the host leader’s approval: the visiting leader sees a significant increase in approval within both subsets (triangle dots). Perhaps unsurprisingly, the effect of a high-level visit by a popular foreign leader on their own approval is large. While the heterogeneous effects shown in Figure 6 should not be interpreted as causal, taken together these patterns suggest that the primary effect of public diplomacy we identified is not simply driven by the incentives of the host leader.

Soft-Power Honeymoon?

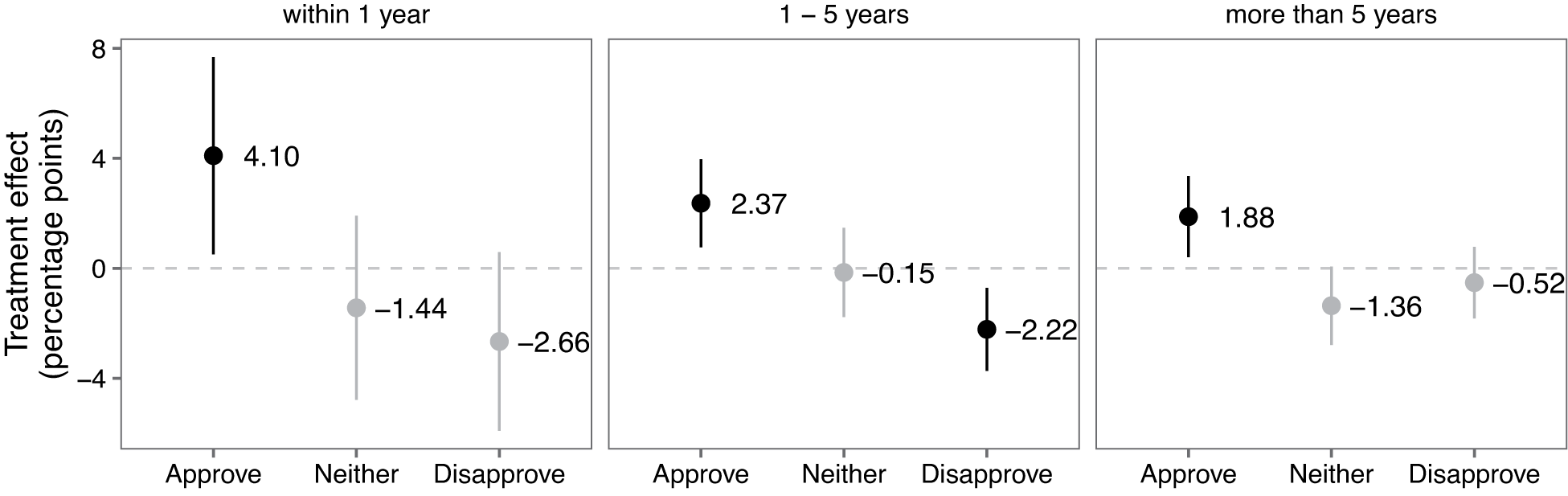

Finally, we consider whether visiting leaders’ time in office conditions the effect of their visit. On one hand, leaders with who have established track records and relatively high familiarity among global audiences may be more effective public diplomats. This would indicate that leaders’ reputation and credibility are important in generating soft-power resources. On the other hand, if people start less informed and develop their opinion based simply on the number of messages they have received on a topic (Zaller Reference Zaller1992), their less-entrenched opinions may be more malleable in response to visits by relatively new foreign leaders.

Our results indicate that new leaders have a public-diplomacy advantage. Within the first year of their tenure, leaders appear to have roughly double the effect on host-country approval levels that they have after five or more years in office (Figure 7). This “honeymoon” effect may suggest that public diplomacy’s influence relies to a considerable extent on low levels of information held by foreign citizens rather than mainly being the product of hard-earned reputations for credibility developed by experienced leaders.

Figure 7. OLS Regression Results by the Number of Years since a Visiting Leader Assumed Office

Note: Treatment effects using the respondents interviewed within five days before/after the first day of a high-level visit. Vertical bars are 95% confidence intervals. Estimates statistically significant at the 0.05 level are highlighted in black.

Conclusion

In this article, we establish a causal connection between the visits of leaders from nine major countries and mass opinion in 38 host countries. We demonstrate that there is a substantial positive shift in approval of the leadership of a visiting country after a high-level visit, relative to the comparable previsit period. We further present evidence that it is public-diplomacy activities in particular that drive the effects of visits on foreign public opinion. When we focus on visits without evidence of public diplomacy, the effects disappear, but when we remove visits with economic or security announcements, the effects remain. The effects of high-level visits are relatively long lasting and are not driven by just the U.S. cases.

These findings support the core and largely untested assumption behind most of the literature on public diplomacy: public diplomacy actually sways foreign public opinion. This is also the core assumption behind the argument that public diplomacy is an effective tool for increasing a country’s soft-power resources. We see our contribution as providing a solid empirical foundation for moving the related literature in international relations forward, including debates about the nature of international power. Scholars and policy makers can better assess the substantive influence of high-level public diplomacy—a ubiquitous feature of modern international relations—on specific policy goals, if they are able to estimate the actual effects of public diplomacy activities on mass opinion in the targeted countries.

We explore further theoretical implications of our findings by showing that there is weak evidence of a hard edge to soft power. Only for extremely large power differentials is the effect of a high-level visit conditioned by the hard-power imbalance between a strong visitor and a weaker host. However, in most cases, hard-power imbalance does not appear to create any soft-power advantage. We also show that there is little evidence that unpopular host leaders can increase their own domestic support by leveraging a visitor’s relative popularity or that visiting leaders are unable to conduct effective public diplomacy when their hosts are unpopular. Finally, it appears that newer leaders have a larger potential to increase foreign approval, suggesting that a well-established reputation is not central to this effect.

Many important questions remain to be addressed regarding the effects of high-level visits and other modes of public diplomacy. For example, future research should examine conditions under which high-level visits produce the largest changes in foreign public opinion. Which leaders or governments are most effective, which audiences are most receptive, and how do these factors interact? Our exploratory analyses are a first step in this direction, but there is much work remaining to better understand effect heterogeneity, which should in turn lead to more precise theory of the nature and consequences of public diplomacy. Additionally, establishing a baseline effect of high-levels visits (a high profile, but impermanent form of public diplomacy) allows for an examination of whether (or when) other types of public diplomacy, such as government-sponsored events or cultural/educational exchange programs directed at promoting mutual understanding, affect foreign public opinion in comparable ways.

Finally, our results provide a potential avenue through which to better understand how public opinion forms on a range of important policy issues. The effects of foreign public opinion on international outcomes is closely tied to the ability to influence that opinion, which we demonstrate in this article. Our findings should energize further investigation into the nature of foreign public opinion formation and its downstream effects on policy outcomes, such as building military coalitions (Goldsmith and Horiuchi Reference Goldsmith and Horiuchi2012) or ratifying international treaties. Overall, this study provides strong, causally identified evidence challenging the perspective that public diplomacy can be easily dismissed as a mere performance. High-level visits have a significant, positive influence on foreign public opinion, and a variety of countries have access to this tool.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000393.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and/or data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/15GBXD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Earlier versions of this paper were presented in a seminar at the Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research (Tokyo, Japan) on November 14, 2019, the Asian Online Political Science Seminar (AOPSSS) on May 6, 2020, a virtual ISA panel on May 19, 2020, and Yale Conference on Japanese Soft Power in East Asia on March 25, 2021. We thank Alexander Agadjanian, Charles Crabtree, Christina Davis, Naima Green-Riley, Dotan Haim, Hans Hassell, Ingrid d’Hooghe, Josh Kertzer, Risa Kitagawa, Tetsuro Kobayashi, Yoshiharu Kobayashi, Jenny Lind, Tyler Jost, Matt Malis, Mark Souva, Atsushi Tago, and other participants of the seminars for useful comments and information. We also thank Kayla Chivers, Stephanie Gill, Vanna Har, and Anna Williams for research assistance.

FUNDING STATEMENT

Goldsmith gratefully acknowledges support under an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT140100763).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors affirm this research did not involve human subjects.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.