No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

Recent Case Developments

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 06 January 2021

Abstract

- Type

- Notes

- Information

- American Journal of Law & Medicine , Volume 41 , Issue 2-3: The Iron Triangle of Food Policy , May 2015 , pp. 505 - 513

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of Law, Medicine and Ethics and Boston University 2015

References

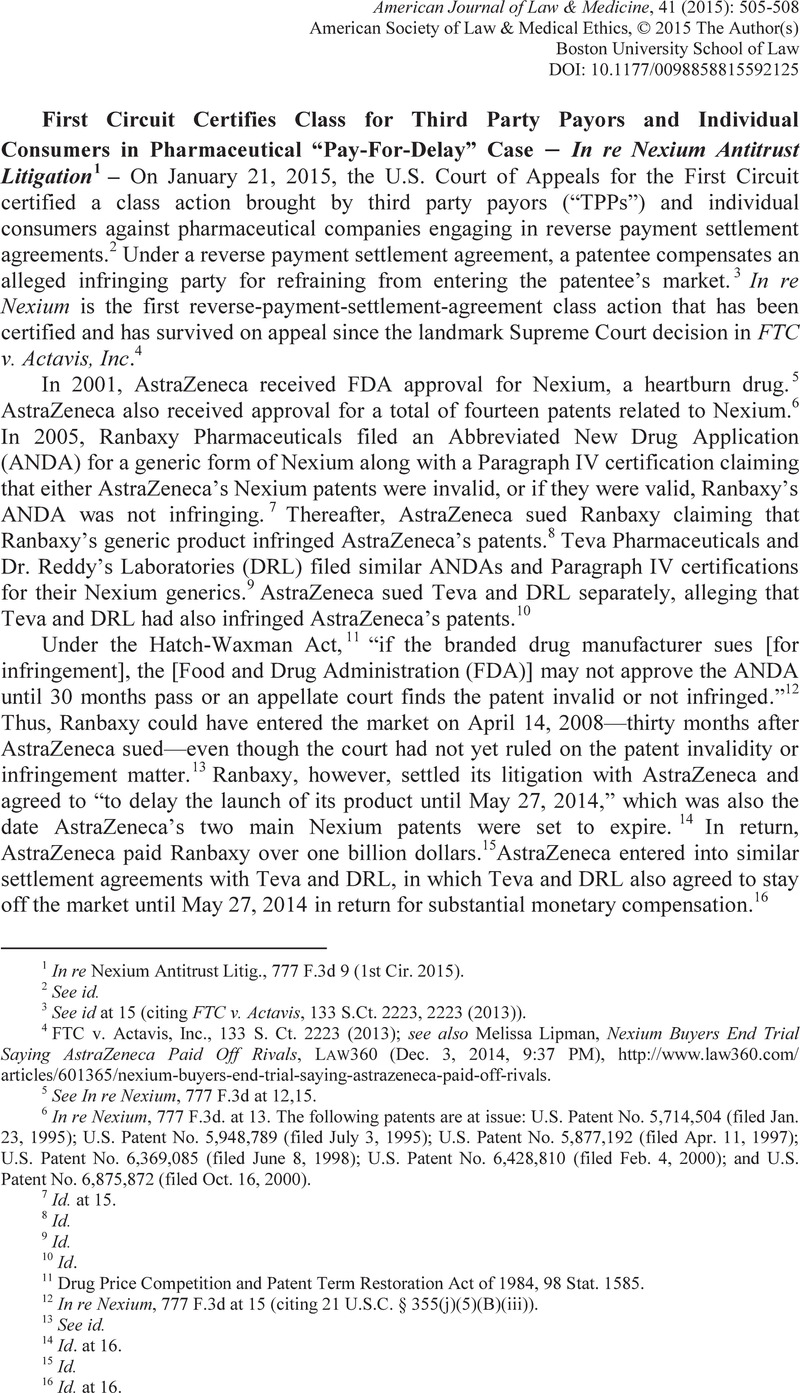

1 In re Nexium Antitrust Litig., 777 F.3d 9 (1st Cir. 2015).

2 See id.

3 See id at 15 (citing FTC v. Actavis, 133 S.Ct. 2223, 2223 (2013)).

4 FTC v. Actavis, Inc., 133 S. Ct. 2223 (2013); see also Melissa Lipman, Nexium Buyers End Trial Saying AstraZeneca Paid Off Rivals, Law360 (Dec. 3, 2014, 9:37 PM), http://www.law360.com/articles/601365/nexium-buyers-end-trial-saying-astrazeneca-paid-off-rivals.

5 See In re Nexium, 777 F.3d at 12,15.

6 In re Nexium, 777 F.3d. at 13. The following patents are at issue: U.S. Patent No. 5,714,504 (filed Jan. 23, 1995); U.S. Patent No. 5,948,789 (filed July 3, 1995); U.S. Patent No. 5,877,192 (filed Apr. 11, 1997); U.S. Patent No. 6,369,085 (filed June 8, 1998); U.S. Patent No. 6,428,810 (filed Feb. 4, 2000); and U.S. Patent No. 6,875,872 (filed Oct. 16, 2000).

7 Id. at 15.

8 Id.

9 Id.

10 Id.

11 Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, 98 Stat. 1585.

12 In re Nexium, 777 F.3d at 15 (citing 21 U.S.C. § 355(j)(5)(B)(iii)).

13 See id.

14 Id. at 16.

15 Id.

16 Id. at 16.

17 In re Nexium (Esomeprazole) Antitrust Litig., 908 F. Supp. 2d 1360 (J.P.M.L. 2012) (listing the six original lawsuits).

18 Id. at 1361. The six transferred actions were: Prof'l Drug Co. v. AstraZeneca AB, No. 1:12-11609 (D. Mass. filed Aug. 29, 2012); Meijer, Inc. v. AstraZeneca AB, No. 3:12-05443 (D.N.J. filed Aug. 28, 2012); Value Drug Co. v. AstraZeneca PLC, No. 3:12-05525 (D.N.J. filed Sept. 4, 2012); Fraternal Order of Police Miami Lodge 20, Ins. Trust Fund v. AstraZeneca LP, No. 2:12-04893 (E.D. Pa. filed Aug. 24, 2012); N.Y. Hotel Trades Council & Hotel Ass'n of N.Y.C., Inc. Health Benefits Fund v. AstraZeneca AB, No. 2:12-04898 (E.D. Pa. filed Aug. 24, 2012); and Rochester Drug Co-Operative, Inc. v. AstraZeneca AB, No. 2:12-04911 (E.D. Pa. filed Aug. 27, 2012). Id.

19 In re Nexium, 777 F.3d at 14 (“[D]efendants provided nothing to AztraZeneca other than an agreement not to compete.”).

20 Id.

21 Id. at 13. Teva finally launched the first generic version of Nexium in February 2015. See Da Hee Han, Teva Launches Generic Nexium, Monthly Prescribing Reference (Feb. 17, 2015), http://www.empr.com/teva-launches-generic-nexium/article/398508/.

22 In re Nexium, 777 F.3d at 14.

23 In re Nexium (Esomeprazole) Antitrust Litig., 297 F.R.D. 168 (D. Mass. 2013).

24 In re Nexium, 777 F.3d at 14.

25 Id. Before a decision was reached in this appeal, the jury at the district court level returned a verdict in favor of the defendants. This verdict does not preclude class certification by the First Circuit because district court proceedings may continue in tandem with appellate proceedings. See id. at 14 n.8. The plaintiffs may appeal the verdict; thus the First Circuit may potentially hear many post-trial motions. See id.

26 See id at 18.

27 See id.

28 Id at 19.

29 Id. at 18-19.

30 Id. at 18-20.

31 Id.

32 Id. at 22.

33 Id. at 20.

34 See id.

35 Id. at 31.

36 Id. at 29.

37 Id. at 30.

38 Id. at 30.

39 Id. at 30 (stating that “if common issues ‘truly predominate over individualized issues in a lawsuit, then the addition or subtraction of any of the plaintiffs to or from the class [should not] have a substantial effect on the substance or quantity of evidence offered.” (citing Vega v. T-Mobile USA, Inc., 564 F.3d 1256, 1270 (11th Cir. 2009) (alteration in original, citation omitted)).

40 Id. at 31 (citing Messner v. Northshore University Healthsystem, 669 F.3d 802, 826 (7th Cir. 2012)).

41 Id. at 14.

42 Id. at 34-35.

43 Id. at 33.

44 See id. at 34.

45 Id. at n. 29.

46 See id. at n. 29.

47 Id. at 35.

1 Missouri v. Harris, No. 2:14-cv-00341-KJM-KJN, 2014 WL 4961473, (E.D. Cal. Oct. 2, 2014).

2 Act of June 6, 2010, ch. 51, § 1, 2010 Cal. Stat. 430 (codified as amended at Cal. Health and Safety Code § 25995 (West 2010 & Supp. 2015)).

3 Cal. Health and Safety Code § 25990 (West 2010).

4 First Amended Complaint to Declare Invalid and Enjoin Enforcement of AB1437 & 3 CA ADC § 1350(d)(1) for Violating the Commerce and Supremacy Clauses of the United States Constitution at 4, Harris, 2014 WL 4961473 (No. 2:14-cv-00341-KJM-KJN), 2014 WL 1245038 [hereinafter Harris Complaint].

5 Harris, 2014 WL 4961473 at *17.

6 Id.

7 Harris, 2014 WL 4961473, appeal docketed, No. 14-17111 (9th Cir. Oct. 28, 2014).

8 Prevention of Farm Animal Cruelty Act, § 3, 2008 Cal. Stat. A-318 (effective 2015) (codified as amended at Cal. Health and Safety Code § 25990 (West 2010)).

9 Id.

10 Id. The Farm Cruelty Act will change requirements for veal crates, battery cages, and sow gestation crates. Cal. Health and Safety Code § 25991 (West 2010). “Veal crates” are used to isolate calves used for veal, which is “[m]eat from a calf that weighs about 150 pounds.” Glossary, Nat'l Agric. Law Ctr., http://nationalaglawcenter.org/ag-law-glossary/ (last visited May 21, 2015) (emphasis omitted). A “battery cage” is a “wire-mesh cage used to house [egg-laying hens] during laying season.” Id. A “sow” is a “[f]emale swine having produced one or more litters.” Id. A “gestation crate” is where sows are kept during the period between conception and birth of a litter. Id.

11 Laird, Lorelei, States Cry Fowl, California's Ban on Standard-Caged Birds Poses a Chicken-Egg Problem, 100 A.B.A. J. 17, 18 (2014)Google Scholar (battery cages are the U.S. industry standard and are used to produce over 90 percent of eggs in the united states).

12 See McNabb, Sarah, Comment, California's Proposition 2 Has Egg Producers Scrambling: Is it Constitutional?, 23 San Joaquin Agric. L. Rev. 159, 166 (2014)Google Scholar (“As many as eleven hens can be housed in one very small cage, measuring approximately eighteen by twenty inches…. Such confined conditions also prevent hens from partaking in many of their natural behaviors ….”).

13 Laird, supra note 11, at 18.

14 Act of June 6, 2010, ch. 51, § 1, 2010 Cal. Stat. 430 (codified as amended at Cal. Health and Safety Code § 25995 (West 2010 & Supp. 2015)).

15 Id.

16 Cal. Health and Safety Code § 25995 (West 2010 & Supp. 2015).

17 McNabb, supra note 10, at 163.

18 Harris Complaint, supra note 4, at 4, 23.

19 Id. at 19, 24; see also 21 U.S.C. § 1052(a) (2010) et seq.

20 McNabb, supra note 12, at 160. The Commerce Clause provides Congress the power to “regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States. U.S. Const., art. I, §8, cl. 3. However, the Commerce Clause is also read to limit the authority of individual states of the U.S. to regulate interstate commerce, known as the Dormant Commerce Clause.

21 Harris Complaint, supra note 4. Plaintiffs argue that California realized that Proposition 2 would impose a great cost to farmers in California and would thus negatively impact the California egg industry. Id. at 3. Thus, in their complaint they assert, “[t]he new capital costs and increased production costs associated with complying with Prop 2 would have placed California egg producers at a significant competitive disadvantage…. [f]aced with the negative impact Prop 2 would have on California's egg industry starting in 2015….” California passed Assembly Bill 1437. Id at 11.

22 Id. at 4 (“By conditioning the flow of goods across its state lines on the method of their production, California is attempting to regulate agricultural practices beyond its own borders.”).

23 Id. at 13-14. The California Department of Food and Agriculture (“CAD”) promulgated regulations that establish minimum dimensions based on floor space per bird stating, “An enclosure containing nine (9) or more egg-laying hens shall provide a minimum of 116 square inches of floor space per bird.” Prevention of Farm Animal Cruelty Act, § 3, 2008 Cal. Stat. A-318 (effective 2015) (codified as amended at Cal. Health and Safety Code § 25990 (West 2010)). Plaintiffs allege that these guidelines may not truly be in compliance with Assembly Bill 1437 or § 25990(a)-(b). Harris Complaint, supra note 4, at 12. Therefore, they claim that compliance with the CAD regulations will result in a 12% increase in overhead whereas true compliance with Assembly Bill 1437 and § 25990 (a)-(b) will result in a 34% or more increase in overhead. Id. at 19. Plaintiffs circumvent the argument that farmers could simply buy California compliant crates for those eggs to California on a cyclical demand rationale, stating “[b]ecause demand for eggs varies greatly throughout the year, egg producers in other states cannot simply maintain separate facilities for their California-bound eggs. In high-demand months, Plaintiffs' farmers may not have enough eggs to meet California demand if only a fraction of their eggs are produced in compliance with AB1437.” Id.

24 Id. at 10 (“California …imports…4 billion eggs from other states.”).

25 Id. at 20.

26 Missouri v. Harris, No. 2:14-cv-00341-KJM-KJN, 2014 WL 4961473, at *3 (E.D. Cal. Oct. 2, 2014) (quoting Cal. Code Regs. tit. 3, § 1350 (2013)) (internal quotation marks omitted).

27 Id. at *4 (Plaintiff's claim that “the people most directly affected by California's extraterritorial regulation … have no representatives in California's Legislature and no voice in determining California's agricultural policy”).

28 Harris Complaint, supra note 4, at 13.

29 Id. at 15.

30 Id. at 14.

31 Id. at 19.

32 Id. at 17-19. Plaintiffs quote language from 21 U.S.C. § 1052(b), which says: “For eggs which have moved or are moving in interstate or foreign commerce, no State or local jurisdiction may require the use of standards of quality, condition, weight, quantity, or grade which are in addition to or different from the official Federal standards ….”

33 Id.

34 Missouri v. Harris, No. 2:14-cv-00341-KJM-KJN, 2014 WL 4961473, at *2 n. 3 (E.D. Cal. Oct. 2, 2014) (“A [P]arens patriae doctrine … [is] a doctrine by which a government has standing to prosecute a lawsuit on behalf of a citizen, esp. on behalf of someone who is under a legal disability to prosecute the suit.” (quoting Black's Law Dictionary 1221 (9th ed. 2009)).

35 Id. at *2.

36 Id. at *7, *12-*13. The District Court found that Plaintiffs did not allege anything to suggest eggs are a vital commodity necessary to preserve plaintiffs' citizens' health, comfort and welfare. Id. at *12. Moreover, the Court found that fluctuating egg prices do not amount to a concerning effect on the Plaintiff states' general population. Id. Succinctly, the Court found that the Harris Complaint does not “allege injury to consumers as a result of the shell egg laws but rather an injury to plaintiffs' egg farmers.” Id. at *13. The Court found that because the plaintiffs failed to allege a quasi-sovereign interest in the well being of egg consumers that they lack parens patriae standing. Id.

37 Id. at *9 (“To have standing [under parens patriae] the State must assert an injury [that is] a quasi sovereign' interest… quasi sovereign [does not include] ‘sovereign interests, proprietary interests, or private interests pursued by the State as a nominal party.”).

38 Id. at *14 (denying standing because “where a dispute hangs on future contingencies that may or may not occur, it may be too impermissibly speculative to present a justiciable controversy.”).

39 Appellant's Brief, Missouri v. Harris, No. 14-17111 (9th Cir. Mar. 4, 2015).

40 Id.

41 Brief for the American Farm Bureau Federation as Amicus Curiae in Support of Appellants at 5, Harris, No. 14-17111.

42 Appellant's Brief, supra note 39, at 18.

43 Id. at 52 (arguing that a dismissal on grounds of subject matter jurisdiction was a dismissal on the merits). The Appellants cited 9th Circuit case law stating, “A case dismissed for lack of subject matter jurisdiction should be dismissed without prejudice so that a plaintiff may reassert his claims in a competent court.” Frigard v. United States, 862 F.2d 201, 2014 (9th Cir. 1988).

44 Order Granting Motion to Extend Filed by Appellees, Harris, No. 14-17111.

45 Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Auth., 297 U.S. 288, 346-48 (1936) (“The Court developed, for its own governance in the cases confessedly within its jurisdiction, a series of rules under which it has avoided passing upon a large part of all the constitutional questions pressed upon it for decision”).

46 For a summary of the U.S. states with Animal Confinement Statutes, see Elizabeth R. Rumley, States' Farm Animal Confinement Statutes, Nat'l Agric. Law Ctr., http://nationalaglawcenter.org/state-compilations/farm-animal-welfare/ (last visited May 21, 2015).

47 49 U.S.C. § 80502 (2012).

48 7 U.S.C. §§ 1901-07 (2012).

49 Supra note 47.

50 Supra note 48, at § 1902.

51 Sullivan, Sean P., Empowering Market Regulation of Agricultural Animal Welfare Through Product Labeling, 19 Animal L. 391, 396 (2013)Google Scholar.

52 Mike Dorf, The King Amendment, Dorf on Law (Dec. 10, 2013) http://www.dorfonlaw.org/2013/12/the-king-amendment.html. The proposed language of the King Amendment is provided below:

In General.—Consistent with Article I, section 8, clause 3 of the Constitution of the United States, the government of a State or locality therein shall not impose a standard or condition on the production or manufacture of any agricultural product sold or offered for sale in interstate commerce if—

such production or manufacture occurs in another State; and

the standard or condition is in addition to the standards and conditions applicable to such production or manufacture pursuant to—

Federal law; and

the laws of the State and locality in which such production or manufacture occurs.

H.R. 2642, 113th Cong. § 11312 (as passed by House, July 11, 2013).

53 See, e.g., The King Amendment: A disaster that didn't happen, Humane Society (Feb. 4, 2014) http://www.humanesociety.org/issues/confinement_farm/king-amendment.html.

54 Id.