No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

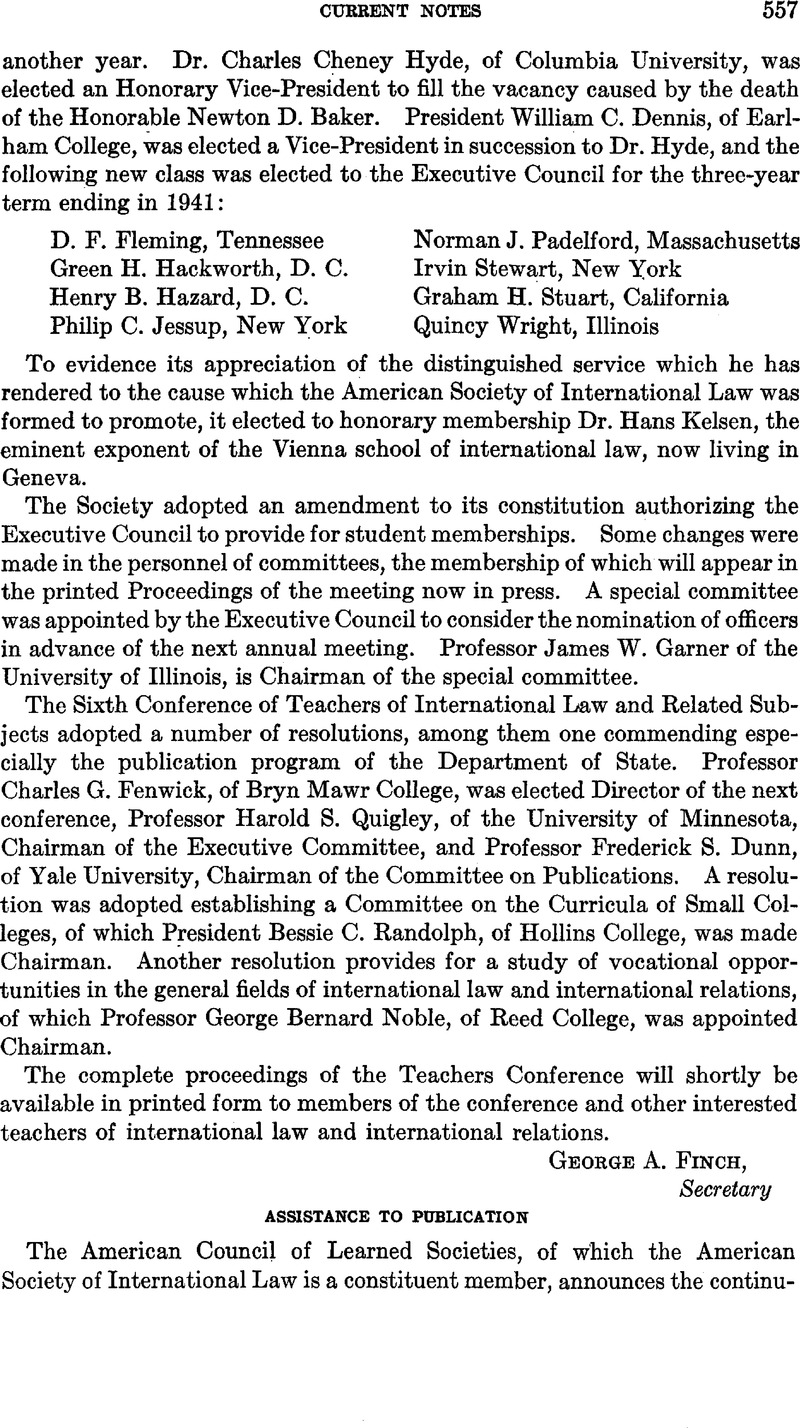

Assistance to Publication

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 April 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Current Notes

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © by the American Society of International Law 1938

References

1 The resolution is quoted from the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, May 16, 1938.

2 This article reads as follows: “The high contracting parties, while they recognize the guarantees stipulated by the Treaties of 1815, and especially by the Act of November 20, 1815, in favor of Switzerland, the said guarantees constituting international obligations for the maintenance of peace, declare…”

3 The resolution reads as follows: “The Council of the League of Nations, while affirming that the conception of neutrality of the members of the League is incompatible with the principle that all members will be obliged to cooperate in enforcing respect for their engagements, recognizes that Switzerland is in a unique situation, based on a tradition of several centuries which has been explicitly incorporated in the law of nations; and that the members of the League of Nations, signatories of the Treaty of Versailles, have rightly recognized by Article 435 that the guarantees stipulated in favor of Switzerland by the Treaties of 1815 and especially by the Act of November 20, 1815, constitute international obligations for the maintenance of peace. The members of the League of Nations are entitled to expect that the Swiss people will not stand aside when the high principles of the League have to be defended. It is in this sense that the Council of the League has taken note of the declaration made by the Swiss Government… in accordance with which Switzerland recognizes and proclaims the duties of solidarity which membership of the League of Nations imposes upon her, including therein the duty of cooperating in such economic and financial measures as may be demanded by the League of Nations against a Covenant-breaking state, and is prepared to make every sacrifice to defend her own territory under every circumstance, even during operations undertaken by the League of Nations, but will not be obliged to take part in any military action or to allow the passage of foreign troops or the preparation of military operations within her territory.

“In accepting these declarations, the Council recognizes that the perpetual neutrality of Switzerland and the guarantee of the inviolability of her territory as incorporated in the law of nations, particularly in the Treaties and in the Act of 1815, are justified by the interests of general peace, and as such are compatible with the Covenant….” (League of Nations Official Journal, 1920, pp. 57, 58.)

4 Cf., for instance, Cassin, International Studies Conference, La Sécurité collective, Paris, 1936, pp. 453, 454; Eagleton, Graham, Quincy Wright, Proceedings of the American Society of International Law, 1933, Vol. 27, pp. 63, 138, 157, 158, 163 et seq.; Wright, Quincy, “The Future of Neutrality,” International Conciliation, 1928, No. 242, p. 369 Google Scholar. Cf., however, Jessup, Proceedings of the American Society of International Law, loc. cit., and Zahler, , “Switzerland and the League of Nations, a Chapter in Diplomatic History,” American Political Science Review, 1936, Vol. 30, p. 735 et seq. CrossRefGoogle Scholar

5 The in other respects excellent message of the Federal Council to the Swiss people, recommending Switzerland’s accession to the League, defends this differentiation in a very unconvincing way. Its attempt to differentiate, moreover, between the legal status of neutrality and a policy of neutrality (see Message from the Federal Council of Switzerland concerning the question of the accession of Switzerland to the League of Nations, Cambridge, 1919, p. 36 et seq.) is perhaps still more unreal and legalistic than the former attempt. According to this conception, there would be three possibilities among which the neutral could freely choose: abstention from military measures required by the legal status of neutrality; participation in military measures prohibited by this legal status; and finally the confines wherein the neutral is allowed to maneuver as he likes, that is, to execute all kinds of non-military measures against one or the other warring party who in turn would not be authorized by international law to retaliate with warlike actions. In a concrete historical situation, however, the neutral has to solve, not the legal question whether the belligerent is entitled by a very doubtful rule of international law to oppose a non-military intervention on the part of the neutral by an act of war, but the political problem whether the belligerent is likely to react in this way. And the aim of a far-sighted neutral is not so much to be in the right as to keep out of war. This is the viewpoint which now determines the neutrality policy of the so-called “traditional European neutrals.”

6 See Feuille fédérale, 1917, Vol. III, p. 205.

7 416, 870 Swiss citizens and 11½ cantons voted for, 323,719 citizens and 10½ cantons against Switzerland’s accession to the League, and it has been pointed out (by Brooks, Robert C., “Swiss Referendum on the League of Nations,” American Political Science Review, 1920, p. 479)Google Scholar that 94 votes would have sufficed to destroy the favorable majority of the cantons and thus defeat the accession.

8 That these states, with the exception perhaps of the Scandinavian countries, seem to be satisfied with declaring Article 16 optional, is more of formal than of practical importance. For the goal of all small European states is the same: to keep out of the political and military entanglements of the Great Powers by restoring the traditional neutrality of the pre-war era.

9 See League of Nations Official Journal, 1920, p. 57.