Introduction

Globally, about 2.4 billion people lived with disability in 2019 (Cieza et al., Reference Cieza, Causey, Kamenov, Hanson, Chatterji and Vos2020). In Ghana, the prevalence of disability ranges between 2.1 and 3 per cent of the population (Ghana Statistical Service, 2013; Tetteh et al., Reference Tetteh, Asare, Adomako, Udofia, Seneadza, Adjei-Mensah, Calys-Tagoe, Swaray, Ekem-Ferguson and Yawson2021). Evidence suggests the prevalence of disability is higher among older adults and those with non-communicable diseases (NCDs) (Rowland et al., Reference Rowland, Petterson-Besse, Dobbertin, Walsh and Horner-Johnson2014).

Disability is a multi-dimensional concept; therefore, its conceptualisation and measurement can be complex, varying across time and context (Agaronnik et al., Reference Agaronnik, Campbell, Ressalam and Iezzoni2019; Theis et al., Reference Theis, Steinweg, Helmick, Courtney-Long, Bolen and Lee2019; World Health Organization (WHO), 2020). There are two competing models of disability: medical and social (Swain and French, Reference Swain and French2000; Anthony, Reference Anthony2011). The medical model focuses on an impairment or a health condition as the cause of disability (Swain and French, Reference Swain and French2000; Anthony, Reference Anthony2011). Medical interventions, including diagnosis and treatment, aim to restore the individual to a functioning level (Marks, Reference Marks1997; Sullivan, Reference Sullivan2011). In contrast, in the social model, disability is socially constructed, the consequence of negative labels, prejudice and discriminatory societal attitudes directed at persons with bodily impairments (Anthony, Reference Anthony2011). These discriminatory societal attitudes create barriers for people with disabilities preventing them from participating fully in society (Llewellyn and Hogan, Reference Llewellyn and Hogan2000; Goodley, Reference Goodley2001; Shakespeare and Watson, Reference Shakespeare and Watson2002; Sullivan, Reference Sullivan2011).

Both models of disability have made significant contributions to our understanding of disability, but they have limitations. For instance, the medical model focuses on impairment as an important determinant of disability with the assumption that people with disabilities are dependent, weak, needy and defective, while the social model ignores diseases and injuries as contributing factors (Owens, Reference Owens2015; Retief and Letšosa, Reference Retief and Letšosa2018). The WHO has proposed the International Classification of Functioning, Health and Disability (ICF) model to combine the strengths and deal with the weaknesses of these two competing models (Pinilla-Roncancio, Reference Pinilla-Roncancio2015). This paper employs a variant of the ICF model to examine relationships between NCDs and disability in Ghana.

The ICF model

The ICF model integrates medical and social perspectives of disability using a biopsychosocial approach where health conditions and structural factors mediate how disability is experienced (Peterson, Reference Peterson2005; Mitra and Shakespeare, Reference Mitra and Shakespeare2019), making it a universal framework for understanding, assessing and measuring disability and functioning (WHO, 2002). The validity of the ICF as a tool for understanding disability has been confirmed in Western countries (Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Kemp, Sunderland, Von Korff and Ustun2009; Luciano et al., Reference Luciano, Ayuso-Mateos, Aguado, Fernandez, Serrano-Blanco, Roca and Haro2010; Almazán-Isla et al., Reference Almazán-Isla, Comín-Comín, Alcalde-Cabero, Ruiz, Franco, Magallón, Damián, de Pedro-Cuesta and Larrosa-Montañes2017; Papelard et al., Reference Papelard, Daste, Alami, Sanchez, Roren, Segretin, Lefèvre-Colau, Rannou, Mouthon, Poiraudeau and Nguyen2019), but it has not been applied in non-Western contexts, e.g. sub-Saharan Africa and Ghana. This gap motivated the present study.

The ICF model has two distinct components (Resnik and Plow, Reference Resnik and Plow2009; Castaneda et al., Reference Castaneda, Bergmann and BahiaI2014). The first distinguishes four concepts that operationalise disability: body functions, body structures, activity limitations and participation restrictions (Hemmingsson and Jonsson, Reference Hemmingsson and Jonsson2005; Benson and Oakland, Reference Benson and Oakland2011; Heerkens et al., Reference Heerkens, de Weerd, Huber, de Brouwer, van der Veen, Perenboom, van Gool, Ten, van Bon-Martens, Stallinga and van Meeteren2018). Body functions refer to the physiological functions of body systems, while body structures refer to the anatomy of the body, such as organs, limbs and their components (Benson and Oakland, Reference Benson and Oakland2011). Activity limitations refer to difficulties an individual may have executing activities, while participation restrictions deal with problems he or she may experience in life situations (Aljunied and Frederickson, Reference Aljunied and Frederickson2014; Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Granlund and Augustine2018). Domains of activity limitations and participation restrictions include learning, mobility, self-care, domestic life, interpersonal interactions and relationships, major life areas, and community, social and civic life. The second component of the ICF model examines contextual factors, at both the structural and the individual level. Structural factors include support and relationships, services and policies, and attitudes. These factors act as facilitators of or barriers to functioning in society (Loke et al., Reference Loke, Lim, Someya, Hamid and Nudin2015). Individual-level factors include age, gender, education, religion and lifestyle characteristics.

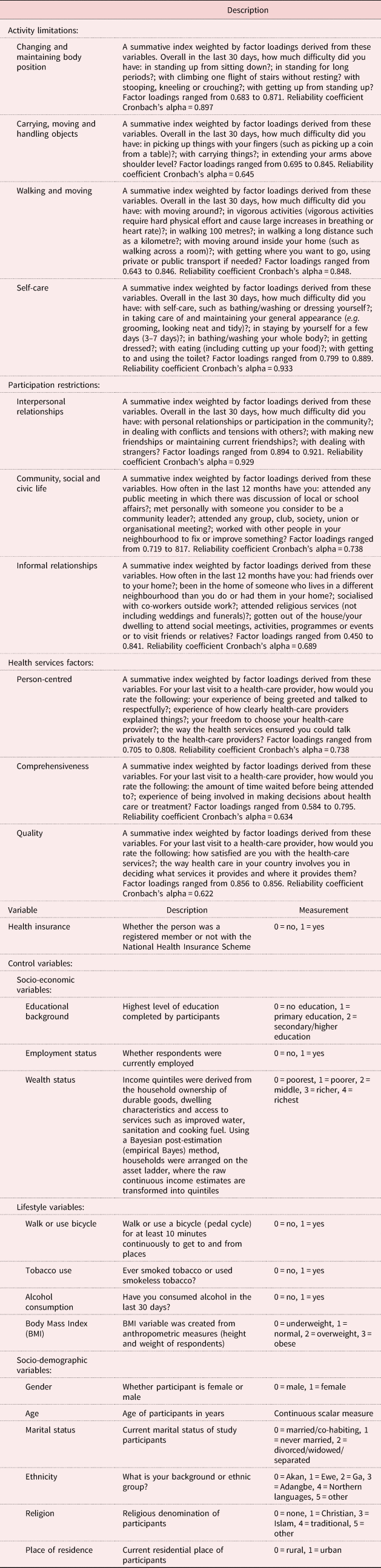

The ICF uses a hierarchical nested classification system and coding scheme to define dimensions of disabilities (see Table 1). For instance, the classification systems changing and maintaining body position, carrying, moving and handling objects, and walking and moving are nested within the mobility domain which, in turn, is nested within activity limitations. The self-care domain is also nested within activity limitations. Similarly, interpersonal relationships and informal relationships are nested within domestic life domains, while community, civic and social life are nested within the major life areas; both, in turn, are nested within participation restrictions. Finally, the classification system health services is nested in the systems, services and policies domain, which, in turn, is nested in the structural level. Because of data limitations, we did not include body functions and body structures in this analysis; we only considered activity limitations and participation restrictions as measures of disability.

Table 1. Domains of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)

Notes: 1. Code letter is ‘b’. 2. Code letter is ‘s’. 3. Code letter is ‘d’. 4. Code letter is ‘e’.

Based on the ICF model, we developed a conceptual framework to explain the links between NCDs and various dimensions of disability (see Figure 1). The framework begins with a health condition (disease) mediated by structural and individual factors. These three variables (health condition, structural factors, individual-level factors) affect how disability is experienced and produced.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of the links between non-communicable diseases and disability.

Source: Adapted from the World Health Organization (2001).

NCDs and disability

NCDs, including hypertension, diabetes and stroke, are the main contributors to disability in Western countries (Klijs et al., Reference Klijs, Nusselder, Looman and Mackenbach2011; Richards et al., Reference Richards, Gouda, Durham, Rampatige, Rodney and Whittaker2016). The resulting functional limitations, such as amputations, blindness and speech difficulties, create challenges in self-care, mobility and social participation (Gregg et al., Reference Gregg, Beckles, Williamson, Leveille, Langlois, Engelgau and Narayan2000; Sturm et al., Reference Sturm, Dewey, Donnan, Macdonell, McNeil and Thrift2002; Elias and Elias, Reference Elias and Elias2007). Even though some policy documents acknowledge the contributions of NCDs to morbidity, mortality and disability in Ghana (Ministry of Health, 2011), accurate knowledge is lacking because epidemiological data are limited. The most common causes of disability in Ghana are road accidents, amputation, cataracts, leprosy, measles and polio (Adjei-Amoako, Reference Adjei-Amoako2016). The most common types of disability are visual impairment, hearing impairment, and intellectual and learning disabilities (Slikker, Reference Slikker2009; Adjei-Amoako, Reference Adjei-Amoako2016).

While NCDs are major risk factors in disability, the opposite may also be true: some evidence indicates people living with disabilities are at risk of developing NCDs, e.g. because of sedentary lifestyles (Dixon-Ibarra and Horner-Johnson, Reference Dixon-Ibarra and Horner-Johnson2014; Krahn et al., Reference Krahn, Walker and Correa-De-Araujo2015). Another risk factor is socio-economic status: people with disabilities with low socio-economic status may have poor nutrition and face challenges in accessing preventive health programmes and affordable health services (WHO, 2011). This may in turn increase their likelihood of living with NCDs. In this paper, we use data from the WHO to examine relationships between NCDs and disability in Ghana.

Methods

Data

Data for the study came from the 2007/2008 Ghana WHO Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE). SAGE is an ongoing programme monitoring the wellbeing of older persons in six countries (China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russia and South Africa). The goal is to provide, strengthen, gather, process and manage data on older persons to facilitate policy planning and monitoring. SAGE includes adults aged 50 years and older, as well as a small group of persons aged 18 years. The SAGE survey asks respondents about their household characteristics, socio-demographic characteristics, perceived health status, preventive and risky health behaviours, chronic conditions, health services coverage and utilisation, subjective wellbeing and social networks. Anthropometric measurements, blood pressure and dry blood spots for biomarkers are also collected. In addition, respondents are asked if they have had a stroke, cancer, diabetes or hypertension.

To select participants, SAGE employed a multi-stage sampling technique, selecting households from 251 Enumeration Areas, with a final 5,373 individuals chosen for interviews. The sample was stratified by administrative region and type of locality, resulting in 20 strata. The final SAGE sample comprised 5,348 individuals (a response rate of 93.8%). The sample for the present study was limited to 4,209 respondents who answered questions on various domains of disability.

Measures

Dependent variables

The dependent variables measuring disability included variables for activity limitations and participation restrictions. Based on the ICF model (WHO, 2001), we created four categories of activity limitations. The first three are under the mobility domain of the ICF model (changing and maintaining body position; carrying, moving and handling objects; walking and moving), and the last is self-care. The questions on the mobility and self-care domains asked participants, overall, how much difficulty they had in the last 30 days executing an activity in either domain. The responses were rated on a five-point Likert scale, with 1 = none, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, 4 = severe and 5 = extreme/cannot do. Because there were very few ‘extreme/cannot do’ answers, they were merged with the ‘severe’ category. Latent variables were created using Principal Component Analysis (PCA), as shown in Table 2. Positive values on the scale indicated the participant had a severe/extreme disability, while negative values indicated mild to no disability. Factor loadings from these scales range from 0.45 to 0.91 and the reliability coefficient Cronbach alpha ranges from 0.62 to 0.93.

Table 2. Operationalisation of scalar and categorical variables

To determine participation restrictions, we used the ICF model categories for domestic life (interpersonal relationships and informal relationships) and major life areas (community, civic and social life). Participants were asked to recall how often they had been involved in the community in the last 12 months. The responses were rated on a five-point Likert scale, with 1 = never, 2 = once or twice per year, 3 = once or twice per month, 4 = once or twice per week and 5 = daily. Positive/negative values on the scale indicated that participants had higher/lower participation. PCA was used to create all latent variables (see Table 2).

Independent and control variables

The focal independent and control variables (see Table 2) were based on the ICF framework that identifies a health condition (disease), environmental factors and personal factors as contributing to disability. We conceptualised three NCD conditions, i.e. hypertension, diabetes and stroke, as health conditions (diseases) and used them as focal independent variables. Following the WHO and Ghana Health Service cut-off points, we defined normal systolic blood pressure as equal to or less than 140 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure as equal to or less than 90 mmHg (WHO, 2010a; Ghana Health Service (GHS) (nd)). The SAGE data include systolic and diastolic measurements taken at three time-points by trained interviewers using a Boso Medistar Wrist BP Monitor Model S (Minicuci et al., Reference Minicuci, Biritwum, Mensah, Yawson, Naidoo, Chatterji and Kowal2014). We used the average of the biometric measures as an indicator of hypertension. Thus, the hypertension measure was created as a binary outcome based on the averages of the systolic blood and diastolic pressure measures and coded 1 if the individual was hypertensive and 0 otherwise. This technique has been used by previous research examining the validity of hypertension measures (Duda et al., Reference Duda, Kim, Darko, Adanu, Seffah, Anarfi and Hill2007; Friedman-Gerlicz and Lilly, Reference Friedman-Gerlicz and Lilly2009; Tenkorang et al., Reference Tenkorang, Sedziafa, Sano, Kuuire and Banchani2015). For the diabetes and stroke variables, study participants were asked if they had ever been diagnosed by a health professional with these conditions. As the responses were binary, ‘yes’ was coded as 1 and ‘no’ as 0. Health services and health insurance were conceptualised as environmental factors, while socio-economic and demographic factors and lifestyle variables were personal measures (see Table 1).

Health services factors were derived using WHO's Monitoring the Building Blocks of Health Systems: A Handbook of Indicators and Their Measurement Strategies (WHO, 2010b: 3). We used three key characteristics to measure health services. The first was person-centredness, i.e. when services are organised around the person, not the disease; when services are person-centred, users perceive health services to be responsive to them. The second was comprehensiveness, i.e. when health services are provided for and appropriate to the needs of the target population. The third was quality. Respondents were asked about their experiences and were instructed to provide answers on a five-point Likert scale, from 1 = very good to 5 = very bad. These responses were reverse-coded for easy interpretation: positive/negative values indicated very good/poor health services.

Analysis

We used ordinary least squares regression (OLS) models because the dependent variables were continuous. Before performing the analysis, we performed diagnostic tests to determine whether the variables met the assumptions of the OLS technique. Because of the hierarchical nature of the SAGE data, with respondents nested within households, and as most regression models are built under the assumption of independence, we imposed a cluster variable to ensure the standard errors were not biased and to produce robust parameter estimates. We used Stata 14.SE for the analysis and adopted the following OLS model:

where $\Upsilon _j$![]() represents the level of disability reported by a respondent j; α0 is the intercept; β1, β2, β3, β4, β5 … β6 are coefficients; and HYP, DIAB, STR, EDU, X 5 and P 6 are the independent and control variables.

represents the level of disability reported by a respondent j; α0 is the intercept; β1, β2, β3, β4, β5 … β6 are coefficients; and HYP, DIAB, STR, EDU, X 5 and P 6 are the independent and control variables.

Results

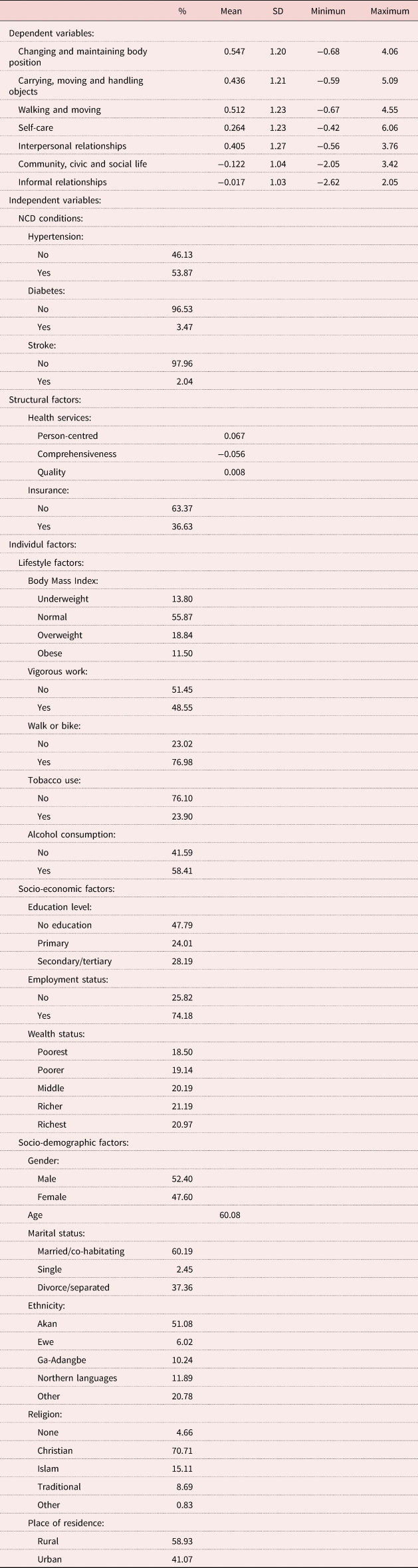

Descriptive results

Table 3 shows the distribution of the study variables. The univariate analysis results clearly show the study participants reported higher activity limitations in all categories (changing and maintaining body position; carrying, moving and handling objects; walking and moving; self-care) and lower participation (community, civic and social life; informal relationships). Results also show that 53.87 per cent of the participants who had systolic and diastolic blood pressure measured were hypertensive. Study participants who reported being diagnosed with diabetes or stroke conditions constituted 3.47, and 2.04 per cent of the sample, respectively. Turning to the environmental factors, respondents generally reported good people-centred and quality health services, but poor comprehensive health services. As for the personal/individual-level factors, those engaging in vigorous work or walking/biking comprised 48.55 and 76.98 per cent of the sample, respectively. Body Mass Index measurements indicated 13.80 per cent of the respondents were underweight and 11.50 per cent were obese. Those with no education represented 47.79 per cent, while those with secondary/higher education comprised 28.19 per cent of the study sample; 74.18 per cent were employed and 25.82 per cent were not. The majority were married, male and lived in rural areas.

Table 3. Univariate distribution of variables

Notes: SD: standard deviation. NCD: non-communicable disease.

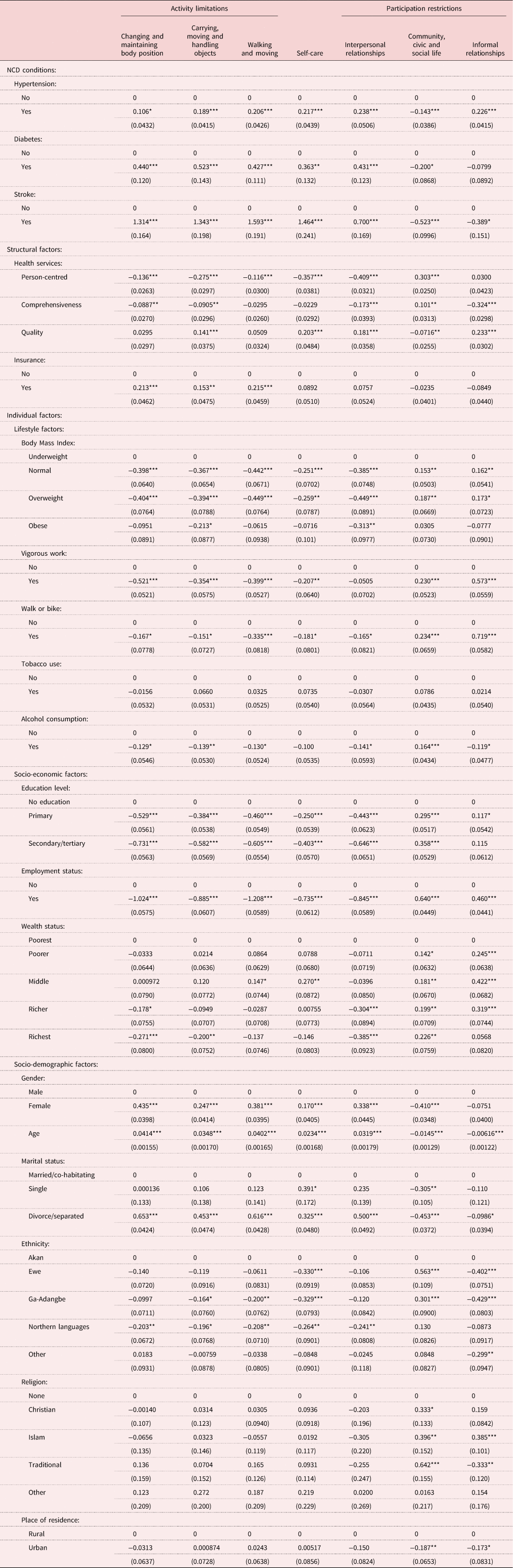

Bivariate results

The bivariate results are presented in Table 4. As the table shows, respondents with NCD conditions (hypertension, diabetes and stroke) reported severe/extreme activity limitations compared to those with no NCD conditions. For instance, respondents affected by stroke reported lower levels of participation in their community, civic and social life and in their informal relationships than those unaffected by stroke. Those who reported receiving very good person-centred and comprehensive health services reported lower levels of activity limitations and lower levels of participation in their interpersonal relationships. However, they reported higher levels of participation in their community, civic and social life. Compared to those without health insurance, those with health insurance reported higher levels of activity limitations. In terms of personal/individual-level factors, compared to those who were underweight, those who were obese reported lower levels on activity limitations when carrying, moving and handling objects, and lower participation in their interpersonal relationships. Similarly, those who engaged in vigorous work or walking/biking reported no/moderate activity limitations and high participation in their community, civic and social life and in their informal relationships than those who did not. Participants with higher education and those who were employed reported no/moderate activity limitations and higher participation in their community, civic and social life than whose without education or who were unemployed. Females reported more severe/extreme activity limitations and lower participation in their community, civic and social life than their male counterparts. Finally, older people reported a higher prevalence of disability (activity limitations and participation restrictions).

Table 4. Bivariate analysis of activity limitations and participation restrictions among people with non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in Ghana

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses.

Significance levels: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

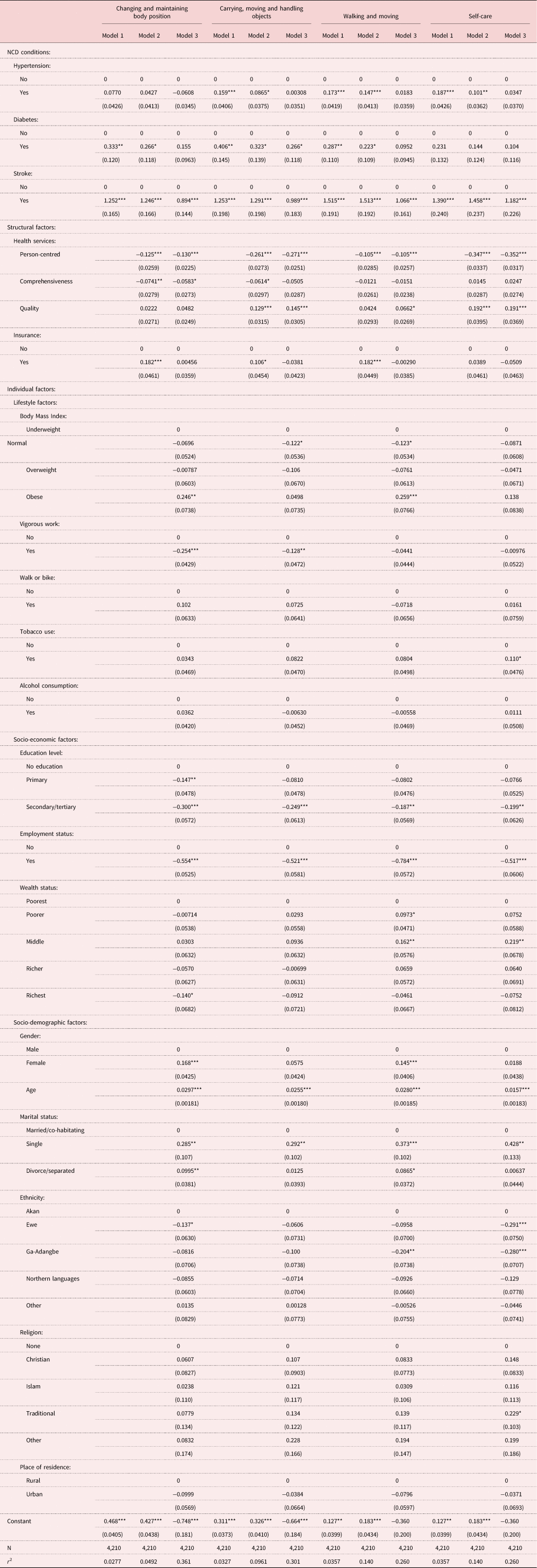

Multivariate results

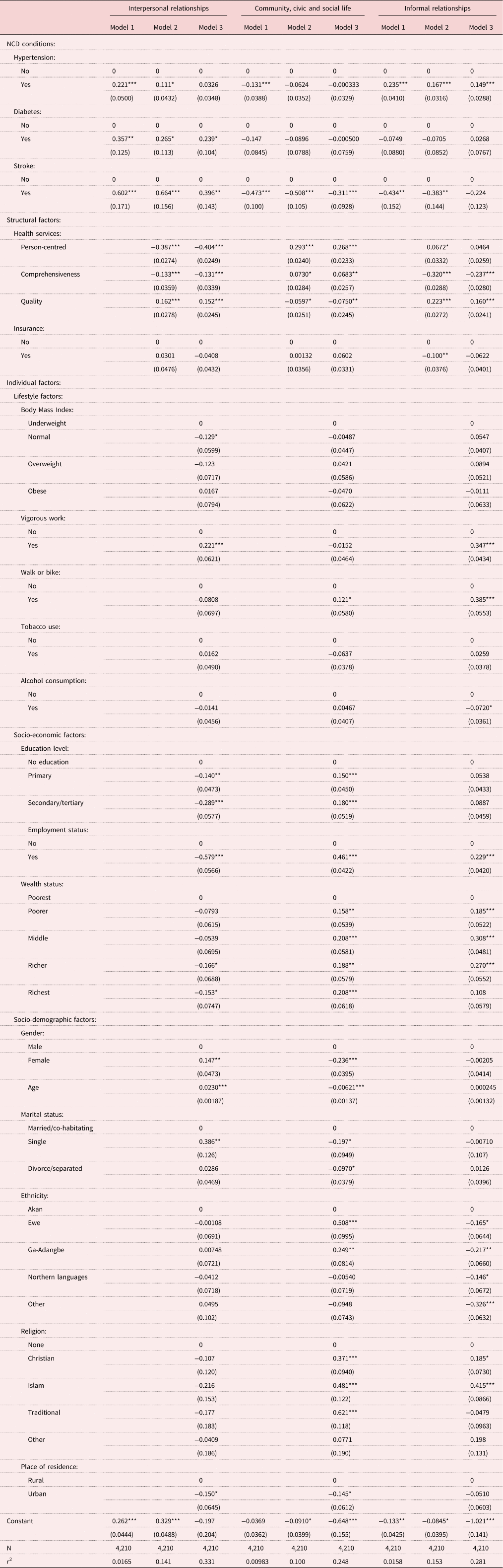

Tables 5 and 6 show the multivariate results for the three models. The first model incorporated NCDs as health conditions, the second included structural factors and the third added individual-level factors (lifestyle, socio-economic and demographic factors).

Table 5. Multivariate analysis of activity limitations among people with non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in Ghana

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses.

Significance levels: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Table 6. Multivariate analysis of participation restrictions among people with non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in Ghana

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses.

Significance levels: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

As Model 1 shows, individuals with diabetes and stroke reported severe/extreme activity limitations (changing and maintaining body position (diabetes: β = 0.333, p < 0.01; stroke: β = 1.252, p < 0.01), carrying moving and handling objects (diabetes: β = 0.406, p < 0.01; stroke: β = 1.253, p < 0.001), walking and moving (diabetes: β = 0.287, p < 0.01; stroke: β = 1.515, p < 0.001) and self-care (stroke: β = 1.390, p < 0.001Footnote 1), and higher participation in their interpersonal relationships than those without diabetes and stroke. Specifically, those reporting a stroke indicated lower participation in their community, civic and social life (stroke: β = −0.473, p < 0.001; hypertension: β = 0.235, p < 0.001) and in their informal relationships (stroke: β = −0.434, p < 0.01) than those who did not. The direction of the coefficients, for instance, indicates that stroke patients have higher coefficients pertaining to activity limitations and lower coefficients pertaining to participation restrictions, thus contributing the highest burden of disability.

Structural factors, including health services characteristics and health insurance, were incorporated into Model 2. As the model shows, study participants who found person-centred health services to be very good reported no/moderate activity limitations (maintaining and changing body position, carrying, moving and handling objects, walking and moving); they also reported lower participation in their interpersonal relationships. Interestingly, further analysis revealed that those who indicated person-centred and comprehensive health services as very good had higher levels of participation in their community, civic and social life.

Model 3 included individual-level factors. Compared to the underweight, the obese reported severe/extreme activity limitations on maintaining and changing body position and walking and moving. Compared to those without education and the unemployed, those with a secondary/higher level of education and the employed reported lower activity limitations and lower participation restrictions in their interpersonal relationships. In contrast, those with higher education and the employed had higher participation in their community, civic and social life or in their informal relationships. Females had higher activity limitations and participation restrictions than males.

Discussion

We used the ICF model to examine how NCDs contribute to disability in Ghana. The ICF model provides a common language to understand disability worldwide (WHO, 2002; Resnik and Plow, Reference Resnik and Plow2009). It serves as a framework to conceptualise how human functioning related to body structures, functions and activities (at the level of the person) and participation (at the level of society) interact with the structural and individual-level factors.

The sudden onset of such NCDs as hypertension, diabetes and stroke could disrupt a person's life, but most interventions focus on organ damage (impairment), with little attention to other aspects of human functioning (Algurén et al., Reference Algurén, Lundgren-Nilsson and Sunnerhagen2009). In this study, stroke emerged as a major contributor to disability; it limited people's functioning and participation in daily activities and in society as a whole. Research in Western countries notes that about 90 per cent of stroke survivors have some disability, with compromised neurological functions (motor, sensory, visual) and/or limited ability to perform daily activities (Glässel et al., Reference Glässel, Kirchberger, Linseisen, Stamm, Cieza and Stucki2010; Sumathipala et al., Reference Sumathipala, Radcliffe, Sadler, Wolfe and McKevitt2011; Silva et al., Reference Silva, Corrêa, Faria, Buchalla, Silva and Corrêa2015; Carvalho-Pinto and Faria, Reference Carvalho-Pinto and Faria2016). Research conducted in sub-Saharan Africa finds stroke survivors have decreased social interactions with neighbours and other relatives and experience difficulty participating in social gatherings (Algurén et al., Reference Algurén, Lundgren-Nilsson and Sunnerhagen2009; Vincent-Onabajo, Reference Vincent-Onabajo2013; Urimubenshi, Reference Urimubenshi2015). In our study, individuals living with diabetes and hypertension did not report severe disability, but such conditions are usually asymptomatic. Participants may not have detected these conditions because of inadequate education, limited access to health care or delayed diagnosis (Aikins, Reference Aikins2003; Lins et al., Reference Lins, Jones and Nilson2010).

Studies in Western countries have demonstrated that individuals with higher education are able to delay the onset of disability or postpone disability to a greater extent than those with less education (Jones and Latreille, Reference Jones and Latreille2009; Montez et al., Reference Montez, Zajacova and Hayward2017; Chatzitheochari and Platt, Reference Chatzitheochari and Platt2019). However, educational level may have less effect once a disability is present. Our results suggest socio-economic factors have a significant effect. For instance, in our sample, those with a higher level of education and the employed were less likely to report disability than those without education and the unemployed. This finding is partly explained by the fact that education enhances knowledge, and those with adequate health knowledge are likely to seek out healthy lifestyle behaviours and health care (Zühlke and Engel, Reference Zühlke and Engel2013; Checkley et al., Reference Checkley, Ghannem, Irazola, Kimaiyo, Levitt, Miranda, Niessen, Prabhakaran, Rabadán-Diehl, Ramirez-Zea, Rubinstein, Sigamani, Smith, Tandon, Wu, Xavier and Yan2014; Schulz et al., Reference Schulz, Kunst and Brockmann2016; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Chiang and Liu2018).

In the ICF model, certain structural-level factors are considered to be contextual factors affecting the functioning of an individual. For instance, in this study health systems had an impact on disability. We found that those who received good person-centred and comprehensive health services were less likely to report disability. Previous research demonstrates that those with disability are more likely to utilise health-care and rehabilitative services to address their functional level (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Pike, Marshall and Ye2016; Reichard et al., Reference Reichard, Stransky, Brucker and Houtenville2019).

Finally, we found some individual-level variables affected disability. For instance, women reported more disability than men; this may be related to women's primary responsibility for the household and their more limited participation in social life (WHO, 2011). We also found that older people were more likely to report activity limitations and participation restrictions. This has been documented elsewhere; research in Western countries has established a strong association between ageing and disability, with decreased functioning in cognitive, physical and sensory domains having a major impact on older adults (Freedman et al., Reference Freedman, Martin and Schoeni2002). The findings further indicate that lifestyle factors affect disability among NCD patients in Ghana. Analyses revealed significant differences between respondents who engaged in physical activity and those who did not. For instance, respondents who engaged in physical activity reported lower activity limitations in changing and maintaining body position and carrying and handling objects, and higher participation in interpersonal relationships and community, civic and social life. Respondents who were obese reported higher activity limitations (in changing and maintaining body position and walking and moving). Our results are consistent with some studies in Western countries that established that engaging in risky lifestyle behaviours increases the likelihood of living with a disability, while adopting healthy behaviours such as physical activity reduces the burden of disability (Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Yee, Diehr, Arnold, Thielke, Chaves, Gobbo, Hirsch, Siscovick and Newman2016; Raina et al., Reference Raina, Ali, Joshi, Gilsing, Mayhew, Ma, Sherifali, Thomson and Griffith2021).

Conclusion

In this research, we investigated the prevalence of activity limitations and participation restrictions among Ghanaians living with NCDs including hypertension, diabetes and stroke. The results clearly show stroke is the largest contributor to disability in the Ghanaian population. We also found those with higher socio-economic status, particularly those with higher education, reported no/moderate disability. Our findings have policy implications. For example, interventions to reduce the burden of disability in the Ghanaian population should include the provision of accessible public spaces for those with activity limitations and participation restrictions.

Despite the interesting findings, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of the study. First, the use of self-reported data may have introduced subjective interpretations of the survey items by respondents, biased by their experiences and culture. Second, we did not examine the issue of reverse causality, even though it could affect the interpretation of the results. We do not know, for instance, whether disability causes NCDs or NCDs cause disability, and future research should certainly address this issue. Unfortunately, the cross-sectional nature of the SAGE data did not allow us to make causal inferences. Third, due to data limitations, we were unable to examine other elements of the ICF including body functions and body structures. Despite the limitations, this study is one of the few in Ghana and sub-Saharan Africa to have developed a comprehensive operationalisation of disability in exploring its relationship with NCDs.

Financial support

This work was supported by Memorial University's Arts Doctoral Completion Award; The Peter Mackey Memorial Graduate Scholarship; and Scotiabank Bursaries for International Study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.