The source

It was with a mixture of surprise and enchantment that I came across the folder containing the manuscript titled ‘The Customs of the Ombala (Capital) of Bailundo’Footnote 1 one afternoon while working at the archives of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) at Houghton Library, Harvard University, in 2011. The text in question is part of a fragmentary account of life in Bailundo, one of the most powerful politiesFootnote 2 in the Central Highlands of Angola. It was written in Umbundu, the vernacular spoken in this region, by missionaries of the North American Congregational Mission between 1903 and the 1930s. Although no dates are mentioned in the source, it refers roughly to the period between the seventeenth century and the gradual establishment of Portuguese colonial rule and Christian missions in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This source is invaluable not only for its content, but also for the fact that it was recorded in the local vernacular. This is important because it gives access both to the Umbundu spoken in Bailundo in the early twentieth century and to the perspective of Umbundu-speaking subjects on what it was like to live in this polity before and after the turn of the twentieth century.

The source addresses social, cultural, political and economic aspects of life in Bailundo as well as significant historical events. It contains important information on daily and ritual life; the different social positionalities inhabited by the subjects of the narrative, especially as far as gender, age, status, race, class and region are concerned; the large trade caravans organized by local rulers that crossed the interior of Angola to the east and west; the wars waged by the inhabitants of Bailundo against the Portuguese military and neighbouring polities; the Umbundu language; Portuguese and missionary presence; local perceptions of colonial relations before and after the Bailundo War (1902–03); the rise and fall of local rulers; political organization; religious practices; kinship relations; local architecture; legal procedures; and food and agriculture.

The manuscript does not mention whose account this is, who recorded it, or when it was produced. What is known is that it was written in the early twentieth century, after the Bailundo War, by Congregational missionaries. My Umbundu-speaking interlocutors in present-day Bailundo have described the language employed in the narrative as both old-fashioned and elaborate. The 20,761-word manuscript in Umbundu was slightly annotated in English by Congregationalist missionary Merlin W. Ennis. It is to be found in a folder titled ‘Umbundu manuscripts with descriptive notes by Merlin Ennis’, which contains the narrative that is the focus of this article plus a collection of songs, a collection of tales, and autobiographical letters in Umbundu by three local pastors of the Congregational mission: Abraham Ngulu, Solino Chiwale Daniele and Samuel Sambundu. The folder with these documents was donated to the ABCFM archives by missionary Una J. Minto, who worked with Ennis in Bailundo. No date for the donation is provided.

The original narrative on Bailundo is divided into four parts, each to be found in a different folder. Parts I, II and IV of the source have titles in Umbundu that have been translated into English only in its index, whereas Part III has only an English title and was given a slightly different title in the index. The titles of the four parts in Umbundu and English are as follows: I. Efetikilo ko Bailundo [index title ‘The Beginnings of Bailundo’], with twenty pages; II. Ovitua Viombala Yinene yo Bailundo [index title ‘The Customs of the Ombala (Capital) of Bailundo’], with seventeen pages; III. Chronicles of the Kings of Bailundo [title provided only in English in the source; index title ‘The Chronicles of the Kings of BailunduFootnote 3 from Ekuikui II to Kalandula’], with eighteen pages; and IV Onduko yo Bailundo [index title ‘The Name, Bailundu, with Chronicles of Early History’], with thirty-five pages. The original document I consulted at Houghton Library has ninety-three pages, of which pages 18 to 38 are missing. Concerning this omission, a descriptive note by missionary Ennis states: ‘It would appear that this portion deals with the circumstances that led up to the war of 1902.’ The reference is to the Bailundo War (1902–03), waged between Portuguese forces and the polity of Bailundo, the result of which was the military subjugation of the Central Highlands of Angola.Footnote 4 The note leads one to believe that Ennis was not responsible for collecting the narratives and raises questions as to whether the omission might be related to the participation of Congregational missionaries in the conflict as mediators between Portuguese authorities and local leaders. It is unknown who was responsible for the omission.

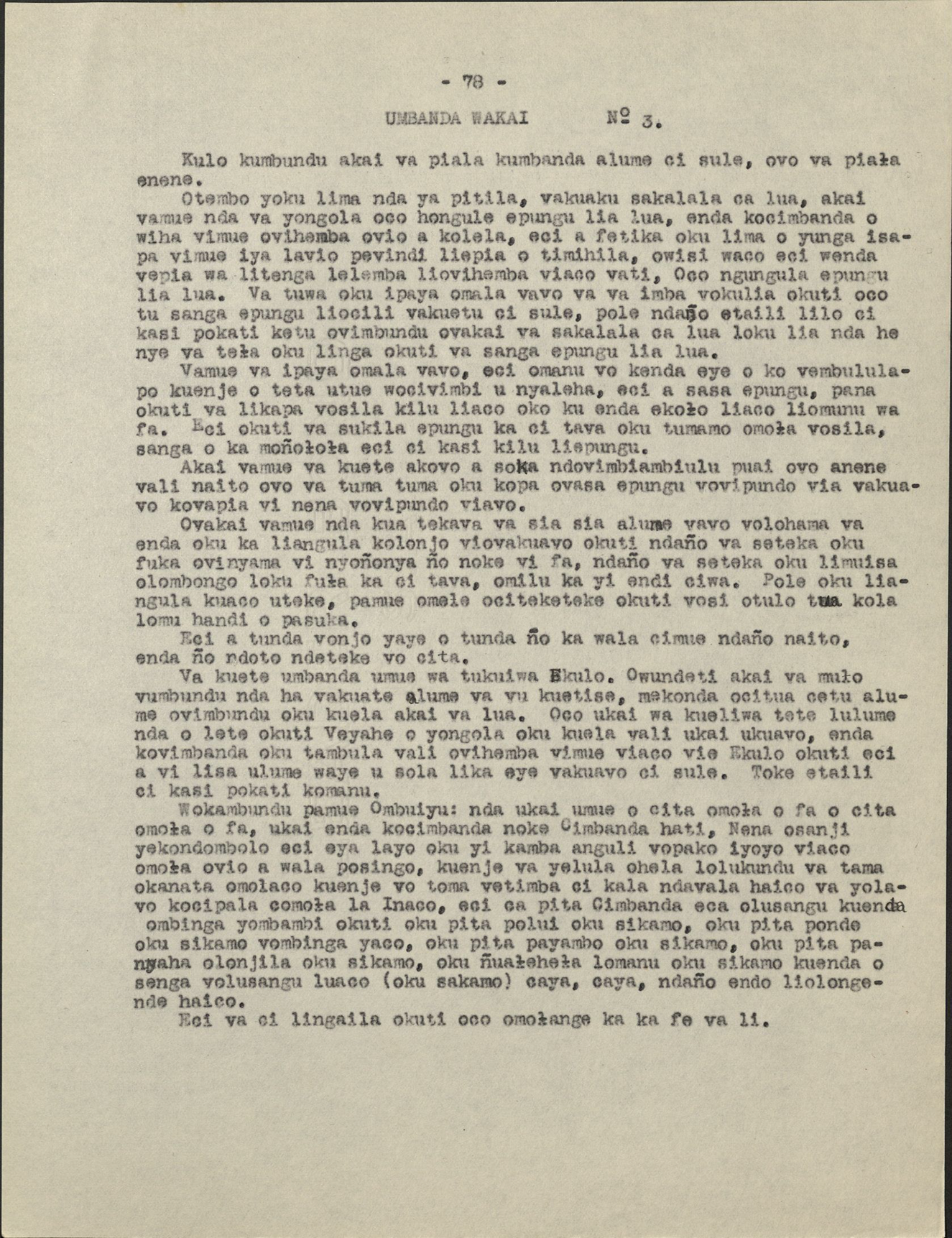

Since the typewritten document available in the archives contains very few erasures, this is probably not the record that was produced in the presence of the narrator(s). Some events are narrated more than once. Whenever this is the case, the different versions are assigned numbers 1, 2, 3 or 5 (see Figure 1). The degree to which the versions differ varies and it is not always the case that there is more than one version of each narrative. Sometimes the same number appears more than once for the same narrative. One cannot be sure whether the different versions concerning the same subject or event are accounts by the same person on different occasions, different accounts by different people, or both. It might be the case that five different people were involved in the production of the narrative but the accounts of one of them were lost (since number 4 is absent). It might also be the case that the narrators were assigned numbers to identify them based on their roles in the mission and were therefore known by these numbers to the missionary who made the record. Whatever the case, the way in which the accounts are numbered and the degree to which they vary lead one to suppose that four different native Umbundu speakers were involved in the production of the manuscript available at Houghton Library. And given that other documents in the same folder are signed by the three pastors mentioned above, one wonders whether they might also have been the authors of the ‘Chronicles’.

Figure 1 Page of the manuscript containing different numbered versions of the narrative on King Numa.

The source's fragmentary character and uncertain authorship reflect the disjunctive nature of its colonial conditions of production. No title was given by its original authors and editors to the partial whole that is made up of the four folders containing the narratives. I have therefore called this publication ‘Chronicles of Bailundo’ based on fragments of the English titles found in the archives so that the title of this publication indexes the fragmentary nature of the source. The text in Umbundu has been transcribed, translated into Portuguese and English, and annotated for publication in this Africa Local Intellectuals series. An annotated sample of the source in English is presented following this article. The supplementary materials published with the article contain the complete original in Umbundu; its complete annotated translation into English; and a complete annotated translation into Portuguese. Although one cannot precisely determine many of the particularities of its narrating subjects because the authors of the account are not named, the source does give access to details and evaluations usually absent from records in which the narrators are the colonizers.

Umbundu is the second most commonly spoken language in Angola today. Yet, historical sources in this language are extremely rare. Most colonial sources on Angola are written in European languages: Portuguese, the language of the colonial administration and the press, and also spoken by Portuguese colonists and some Christian missionaries and travellers; English, the language employed in the correspondence of Protestant missions;Footnote 5 and French, the official language of the Congregation of the Holy Ghost, the largest Catholic mission in Angola.Footnote 6 The history of Angola has thus been largely based on colonial records in European languages, as is usually the case in Southern Africa. ‘Chronicles of Bailundo’ is possibly the only source to extensively narrate, in Umbundu, what it was like to live in Bailundo prior to, during and after the intensification of the Portuguese presence in the Central Highlands in the wake of the Bailundo War. The fact that it was produced from the perspective of subjects of the polity of Bailundo and recorded in Umbundu makes it fundamental for investigations into the history and anthropology of the Atlantic and of Southern and Central Africa in general, as well as, more specifically, of Angola, the Central Highlands and the adjoining regions. This is the case both due to the kinds of information it contains and because it gives access to the perspective of colonial subjects on local society and colonial rule in the language in which these subjects were constituted: Umbundu. And this is especially relevant if one is to make sense of the colonial situation in a way that accounts for its complexity and nuance.

The first part of the document, ‘The Beginnings of Bailundo’, starts with a list of the first olosoma – an Umbundu term usually translated as ‘kings’ – who governed Bailundo (see Figure 2). This list, which one supposes to be based on oral tradition, includes narratives of the feats, characters and reputations of these rulers. No precise dates are provided, but the most important events that occurred during each ruling period are described in relation to major political events in the region: wars against neighbouring states; caravan trade expeditions; and the colonial presence in the form of military posts, Christian missions and contract labour. The second part of the source, ‘Customs of the Ombala of Bailundo’, describes life at court: its architecture; the names and attributions of court members; the different social positionalities occupied by the subjects of Bailundo; and the rituals performed to obtain good harvests, hunt enough game, placate ancestors, guarantee good health and wealth, acquire power, show one's reverence to the elderly and powerful, instate a new king or remove an old one. It ends with an account of how Captain Teixeira da Silva, who became the first captain major of Bailundo in 1896, was welcomed in Bailundo as one of its subjects and took this opportunity to establish Portuguese rule in the region (see Figure 3).

Figure 2 List of the kings who governed Bailundo.

Figure 3 Section on Captain Teixeira da Silva.

The third part of the manuscript, ‘Chronicles of the Kings of Bailundo’, provides further narratives on the lives of later Bailundo rulers. It includes wars waged against neighbouring polities, especially Viye, and resistance against Portuguese colonization. The fourth and final part, ‘The Name, Bailundo’, further explains the criteria on which status was determined in the kingdom of Bailundo: the region from which one comes; the family to which one belongs; how much wealth one possesses; whether one is free or a slave; gender; age; one's abilities and character. It also dwells on the details of government practices, such as the performance of political rituals; what is expected of rulers; who can instate or depose a ruler and how this is done; funerary rituals; sorcery; polygamy in the court; food distribution; how to salute the king; the court tribunal; royal succession; and famine, rain and cultivation rituals. It includes sections on ‘the power of women’ (see Figure 4), sorcerers and diviners; caravan journeys; the architecture of houses in Bailundo; and practices related to child raising, hygiene, cooking, sleeping, marriage, pawning, burial, widowhood and slavery. Thus, subjects that are usually addressed in historical and ethnographic accounts of late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century Bailundo by North Americans and Europeans are explored in this document from the perspective and in the language of Umbundu speakers.

Figure 4 Section on ‘the power of women’ (umbanda wakai).

‘Chronicles of Bailundo’ in context

The ABCFM, founded in Massachusetts in 1810,Footnote 7 was the Congregational organization responsible for the main Protestant mission active in the Central Highlands of Angola between 1881 and 1961.Footnote 8 Bailundo was the site of their first mission station, established in 1881 at the invitation of ruler Ekuikui II. Back then, missionary presence depended on authorization by, and therefore good relations with, the local ruler and his court; as the source puts it, ‘The Soma [local ruler] liked everyone to obey him, both the whites and the Ovimbundu.’

Two missionaries appear in the ABCFM archives as having been somehow involved in the production of the manuscript: Merlin W. Ennis (1874–1964), active in Angola from 1903 to 1944, and Una J. Minto, ‘appointed for life service’ in 1920.Footnote 9 Both worked in the Bailundo mission station. Ennis is described in the register of the missionaries active in the West Central African Mission (as the mission in Angola was then called) as an ‘evangelist’ who did ‘notable work as a translator’. He spent thirty-one years in the Central Highlands of Angola, most of the time in the company of his wife, Elisabeth Ruth Ennis (1881–1961), who joined him in the mission in 1907.Footnote 10 According to the archives, the manuscripts in Umbundu were ‘donated by Una J. Minto’. However, it is not clear what role Ennis and Minto had in the production of the final version of the source. The annotations that precede each of the chapters comprising the manuscript in Umbundu contain an indication in blue ink, possibly added by Minto, that the English description of its contents was authored by Ennis. But one does not know who wrote down the narrative; nor does one know whether the final typewritten version of the text was organized by Ennis, Minto, or someone else. What is known for sure is only that both Ennis and Minto dealt with these papers in some capacity at some point in the history of the Bailundo mission.

Ennis was involved in linguistic and ethnographic work in Bailundo. He is the author of Umbundu: folk tales (Ennis Reference Ennis1962), an unpublished grammar of Umbundu, and a translation of the Bible into this language. Both Merlin and Elisabeth Ennis authored ethnographic writings on the Central Highlands; these included collaborative work with local speakers of Umbundu (Evambi and Ennis Reference Evambi and Ennis1938; Ennis Reference Ennis1945). Since male catechists and pastors were the main collaborators of Congregational missionaries in the dissemination of Christianity throughout the interior of Angola due to their familiarity with both Umbundu and the Protestant religion (Dulley Reference Dulley2015), it is reasonable to suppose that most ethnographic and linguistic sources are the product of collaboration between missionaries and local evangelizers.

In the case of the ‘Chronicles’, although the identity of the authors of the account in Umbundu is unknown, some passages of the narrative lead one to suppose that the narrator is an elderly man connected to the mission. For instance, women are mentioned from the perspective of a man: ‘Here among the Umbundu, women have much power, men little. Theirs is excessive’ (emphasis added). The fact that both women and younger men are mentioned in the source as others implicitly occupying positions of lesser prestige and power contributes to this hypothesis. The narrator's affiliation with the ABCFM mission is hinted at when he mentions that the relation between the polities of Bailundo and Viye used to be one of violent antagonism, but the presence of the Christian missions changed this: ‘[T]oday, because of God's word that united us, there is not so much hatred between us.’

As far as the narrative of specific events is concerned – such as the achievements and shortcomings of the various rulers of Bailundo, the wars waged against neighbouring polities or the Portuguese, the arbitration of local disputes, and the returning of a widowed woman to her family after her husband's death – the source offers many different iterations. This could be due to the existence of more than one narrator, to the variation that is inherent in oral accounts, or to both. Anyway, one should bear in mind that, although the source gives access to the perspective of Umbundu-speaking subjects, this perspective is partial to the extent that its narrators occupied a specific position in the colonial universe: that of elderly men associated with the Protestant mission in Bailundo. Yet, although positioned in a particular way, the narrating subjects shared with other Umbundu-speaking subjects the language in which the account is narrated. Therefore, it gives us access to (at least some of) the categories, perceptions and modes of expression through which the history of Bailundo was understood in Umbundu.

One should, however, bear in mind that the Umbundu in which the account is narrated has probably been edited in the process of its recording. For instance, the repetition that characterizes the expression of emphasis in Umbundu oral accounts has been considerably reduced, if not eliminated. Moreover, the categories employed in the narrative should not be understood as Umbundu concepts independent of colonial expression in Portuguese, for the text in Umbundu is pregnant with influence from the Portuguese language – an influence that manifests itself both in the transliteration of Portuguese terms into Umbundu and in the process of translation between the two languages that formed the basis for missionary work (Dulley Reference Dulley2009). It is significant to note that the standardization of Umbundu orthography and grammar observed in this account is also an outcome of the process through which this language was reduced in Christian missions.

A committee for the establishment of Umbundu orthography was appointed at a special meeting held by Congregational missionaries at the Dondi mission station in October 1921. Missionaries Mr Sanders, Mr Tucker and Mrs Neipp were part of this. It is possible that this manuscript has been revised to comply with the standardization of Umbundu that ensued. This was also the year in which the Portuguese colonial government passed a decree determining that Portuguese was the sole language to be employed in school education, a move that certainly contributed to relegating Umbundu expression to non-literary status.Footnote 11 The systematization of Umbundu that appears in this source is the product of collaboration between Protestant missionaries and native Umbundu speakers. There is no unified orthography for Umbundu in Angola; rather, two different orthographies, produced in colonial Catholic and Protestant missions, are employed up to this date.

The uncertainty that characterizes the authorship of the source also makes itself felt as far as chronology is concerned. Not only does one not know when the record took place, was edited, annotated and donated, but precise indications of dates for the narrated events are also unavailable. The list of the rulers of Bailundo, for instance, is suspended in time. However, time is marked approximately to the extent that some events are said to have taken place during the government of this or that ruler. The polyphony of the narrative in Umbundu, in which different versions of the same event are juxtaposed, contributes to the difficulty in pinpointing when exactly events happened. Yet, the narrative proposes a loosely chronological sequence, in which the reign of one ruler follows that of another. According to the text, the establishment of colonial rule was predicted by Ekuikui II: ‘Sons, you won't be able to contain what is set to happen. You will obey the whites, you will be their slaves, they will be superior to you.’

Colonial rule is mentioned as a period that brought suffering to Umbundu-speaking people; however, it is not the central axis around which the narrative is organized. On the contrary, if colonization appears as an undeniable fact, it is also viewed as the result of the exploitation of the local population by the ruling elite:

Because of the deeds of the sons of kings and the corruption of their fathers, people did not have the strength or desire to help the kings when the whites started to make war on them. Because they said: ‘If we go to war, we'll be eaten. If we don't go to war, we'll be eaten. So, we're all counting on the victory of the whites. They are the kings of the poor.’

How widespread was this vision is unknown. But it points to the hierarchical organization of local society during both caravan trade and Portuguese colonial rule. Hierarchy is expressed in Umbundu in the idiom of okulya – i.e. to eat – in which the more powerful are said to ‘eat’ the more vulnerable. A critique of colonial rule is thus coupled with a critical appraisal of local structures of power.

From the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, the Portuguese presence in Angola was restricted almost exclusively to coastal enclaves and their surroundings. It was only between the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, in the wake of the negotiations conducted at the Berlin Conference (1884–85) and the ensuing pressure on colonial powers to effectively occupy their colonies, that Portugal actively invested in the interiorization of the Portuguese colonial presence.Footnote 12 In the Central Highlands, incursions with the purpose of subjugating this region by military means culminated in the Bailundo War (1902–03), in the aftermath of which the powerful polity of Bailundo lost its political and economic autonomy. This event marks the transition from a time when rival polities in the region organized extensive caravan trade journeys and competed for military and political power to a time in which local authorities became subordinated to the colonial administration, Christian missions intensified their presence, and the pace of socio-political and cultural transformation increased.Footnote 13 Umbundu was the lingua franca employed by the trade caravans that crossed the Central Highlands in the direction of Benguela on the coast and Katanga in the interior. It was also the main language spoken in the twelve polities that held and disputed political power in the region.Footnote 14 It is thus of vital importance for a source in this language to be added to the pool of colonial sources on which the writing of the history that precedes and follows colonization in Angola can be based.

Translation

This manuscript is being published in the Africa Local Intellectuals series in English, Portuguese and Umbundu for the following reasons: (1) for it to be accessible in the original language to speakers of Umbundu, native or not, whether they belong to a community of scholars or not; (2) so that the translation facilitates an approximation to the perspective that is expressed in Umbundu without eliding the language in which it is narrated, making it possible for readers to compare the translation with the original; and (3) translation into both Portuguese and English is because, while Portuguese is a language spoken by most Angolans and ‘Angolanists’, it is not accessible to most non-Lusophone readers. Thus, the availability of this source in English is meant to facilitate access to it by a wider scholarly audience. ‘Chronicles of Bailundo’ was translated from Umbundu into Portuguese by Julino Segunda Dídimo and João Abel Katchumbo. Both are fluent in Portuguese and Umbundu and were able to make the passage from one linguistic context to the other without eliminating elements of Umbundu expression in the Portuguese version. David Rogers translated the document from Portuguese into English.

I have revised the Umbundu transcription and both translations, written the ethnographic notes and edited the manuscript. The ethnographic notes have been added to aid the reader in contextualizing Umbundu terms and socio-cultural practices that are presumably unfamiliar to a wider audience. Many of them draw from my fieldwork in Angola and long-term engagement with Umbundu.Footnote 15 The notes include references to scholarly literature on Angola and have the purpose of making the socio-cultural universe to which the manuscript refers as accessible as possible. If any attempt to access a supposed origin is precluded by the very nature of this source, whose conditions of recording are unknown, it is my intention that the mimesis and displacement that marked the colonial process (Bhabha Reference Bhabha1994) might be experienced in a two-way fashion via the translations provided.

Displacement occurs in any translational process. Translation cannot exhaust the content of the original source, nor is it capable of totalizing it. Rather, it attempts to account for the numerous potentialities of the Umbundu original in the best way possible. In this process, the border between Umbundu and the target languages of translation – in this case English and Portuguese – has been blurred with the purpose of allowing for contagion, by whoever reads the document in Portuguese and English, with the syntax and rhythm of the original in Umbundu.Footnote 16 Translation has striven to ‘umbundize’ Portuguese and English within the limits of intelligibility for the speakers of these languages. For, although the erasure of the subjects who authored this narrative is characteristic of colonialism, their subjective constitution, which occurs in language, is accessible through their expression in Umbundu.

Thus, although the account does not enable us to describe the perspective of singular, named subjects situated historically, socially and politically in a precise way, it gives access to symbolic expression in Umbundu. This is significantly different from accessing Umbundu expression through accounts in European languages; in the latter case, Umbundu conceptualization invades the Portuguese text almost exclusively in the form of transliterations into Portuguese, such as soba (king) and caçula (younger child). In the case of the ‘Chronicles’, the sui generis character of the source relates to the fact that conceptualization in Umbundu is not radically detached from its context of expression.

Umbundu is not legible to the majority of scholars because there is little representation of African languages in academia, a context in which Portuguese is not a dominant language either – a fact certainly related to the marginal position of Portuguese colonialism in the twentieth century. The entanglement of linguistic and political dimensions overdetermines the extent to which the ‘Chronicles’ might be legible to different readers. Thus, the ethnographic notes added to the account whenever its legibility was judged to have been compromised are intended to partially bridge this gap. Meaning in Umbundu is distant from both Portuguese and English not only because Umbundu is a Bantu language and therefore structurally different from European languages; symbolic distance is also related to the fact that the metaphors employed in Umbundu are not familiar to most readers, given their peripherality in the contemporary world.

Umbundu employs very elaborate metaphorical expressions whose understanding depends on familiarity with the linguistic, socio-cultural and political context in which they occur. Ethnographic notes are therefore intended to mediate the gap between literality and metaphoricity that is made apparent by the translational process.Footnote 17 In translation, juxtapositions and disjunctions between the literal and the metaphorical are displaced – for instance, when omoko, the Umbundu word for ‘knife’, is translated as ‘power’. Given that disjunction and displacement always characterize translation, the purpose of rendering this source in Portuguese and Umbundu is not to give the reader access to its content in Umbundu in a transparent way but to make the gaps explicit in order to facilitate the work of reading with and against the grain that characterizes any intercourse with historical sources.

As far as the form and style of the original manuscript are concerned, one must bear in mind that the Umbundu it employs is the product of a series of reductions: of Umbundu phonetics into the Roman alphabet; of the dictionarization of Umbundu vocabulary; of its grammatization based on Western languages; of the elision of the repetition that characterizes the transposition of oral expression into writing. We do not have access to the original narrative that was fixed in writing in the ‘Chronicles’. However, if one were to compare it with the Umbundu that one hears today in Huambo and Bailundo, it is striking that the ‘Chronicles’ do not contain the creation of meaning through repetition, the nuances related to variation in tone, or the liveliness of onomatopoeia usually found in oral Umbundu. This notwithstanding, the narrative retains some important features of orality: the widespread use of metaphoric expressions, reported speech and olosapo (plural of olusapo). Olosapo, which can be translated as both ‘tale’ and ‘proverb’ (cf. Dulley Reference Dulley2010: 117–23), are a narrative form of variable length whose story culminates in a punchline. The image they convey can also inform the choice of Umbundu names, as is the case, for instance, with Mutu-Yakevela, a shortened version of the phrase ‘I am like the aged pumpkin, which even when cooked is never done’.

Although some aspects of Umbundu orality were lost as it was reduced to writing, the text of the ‘Chronicles’ does give us access to other important features of this language, such as the polysemy and irony conveyed by its metaphors and the reproduction of direct speech in the form of dialogues between the participants in significant historical events. It is impossible to know whether the figures mentioned actually said the quoted sentences as they appear in the source. Yet, the manuscript gives us access to the way in which historical events are commonly narrated in oral tradition and dialogues are performed in Umbundu – and the various versions in which the same event is narrated attest to the fact that, although oral narratives follow a style, they also vary. Thus, the manuscript, in its fixation of an oral narrative form, contains both the reduction of Umbundu in the context of colonialism and missionization and features of its oral expression by native Umbundu speakers. It is the result of the convoluted and violent encounters it narrates. Publishing the ‘Chronicles’ invites further investigation of its content, form and style, especially by native speakers of Umbundu.

I would like to end this brief introduction by drawing attention to the photographs that I took during my last visit to Bailundo on 6 November 2019, when I had the opportunity to meet members of its court and visit some of the sites that are mentioned in the ‘Chronicles’ (see Figures 5, 6, 7 and 8). Time has passed and things have changed. Yet, some elements that one finds in the narrative remain significant for present-day inhabitants of Bailundo, albeit in different ways. I hope that this publication will contribute to the continuous writing of this history.

Figure 5 Atambo of Chivukuvuku, Njolomba, Chivangulula and Numa. From left to right: Soba Kesongo (Antonio Epalanga), Soba Kesenje (Mateus Ndingilile), neighbourhood soba (Domingos Manuel) and Soba Chilala.

Figure 6 Etambo of Katiavala. From left to right: Soba Usonehi (Fernando Hossi, the ‘secretary’), Soba Citonga (Francisco) and Soba Chilala.

Figure 7 In the background of this daily scene is the Halavala mount, where the akokoto with the skulls of kings used to be located.

Figure 8 View of contemporary Bailundo from the Halavala mount.

Supplementary materials

The following materials are available with the online version of this article at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0001972021000553>:

• Chronicles of Bailundo (transcription of the original document in Umbundu)

• Crônicas do Bailundo (translation of the complete manuscript from Umbundu into Portuguese)

• Chronicles of Bailundo (translation of the complete manuscript from Umbundu into English)

Acknowledgements

I thank Houghton Library and the United Church of Christ for the permission granted to publish this document. I am grateful to the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) for funding my visits to the archives; to the archivists at Houghton Library for their help and generosity; and to Aramis Silva, Cheryl Schmitz and Alberica Bazzoni for their insightful comments on previous versions of this text.

The kings of Bailundo

1. Ekuikui the Elder I – The insect that cannot be eaten by the bird

2. Hundungulu I

3. Cisende the Elder I

4. Gunji – Who has the pillar; on the day it topples, everything on it will die

5. Civukuvuku

6. Utondosi

7. Ñala Bonge

8. Cisende II

9. Vasovava – I have never seen a kingdom like mine

10. Ekongo – Of the goats

11. Ekuikui II

12. Katiavala

13. Numa

14. Hundungulu II

15. Kalandula

16. Cisende III

17. Jahulu

18. Cingi

19. Kangovi

King Ñala Ekuikui II

He is the most important of the kings. It was during his fireFootnote 2 that the whites became firmly established in the country.

His name is Cisengele-Colongupa. On taking the throne, he said: ‘I am Ekuikui Cikundiakundia Cipuka Kaliwa la Njila [The Larva Cikundiakundia that Cannot Be Eaten by the Bird].’ This means: ‘I escaped; I shall not be defeated by anything.’

During his fire all the inhabitants of other countries began to respect the name of Bailundo more. He vanquished many countries.

One day he sent a message to the Soma of Viye in which he said: ‘As there exists much rancour between us, come to talk properly. Because you are a child and I am older,Footnote 3 it's not good that we provoke each other.’ King Ciponge of Viye replied: ‘Tell him that I wouldn't talk with someone toothless.’ On hearing this, Soma Ekuikui said: ‘Very well.’

And he waited for Ciponge to fetch his bales.Footnote 4 The Soma, Ñala Ekuikui, seized all his cargo. And he told Ciponge's lads: ‘Go to your Lord, my younger brother Ciponge, and tell him that Ekuikui, that toothless man, bites even without teeth. His gums bite hard enough.’

It was in the period of King Ekuikui that the peaceful whites came to this country. This king in part was good for the whites because he allowed them to build in his kingdom, but he also punished them a lot. In his time, the population was large, both slavesFootnote 5 and rich people. But anyone looking at the king's wife would be killed immediately.

He was an extraordinary man in strength and in war. All the surrounding countries – Esele, Viye, Bukusu – obeyed Bailundo. At that time, he perceived that he was someone loved by everyone, whites and Ovimbundu. When he was alive, he always said: ‘Sons, you won't be able to contain what is set to happen. You will obey the whites, you will be their slaves, they will be superior to you.’

Customs of the great ombala Footnote 6 of Bailundo

On assuming government, the king begins by naming the people who will build the kingdom. The names given to them explain the functions to which they correspond and how they are constituted, whether they are free persons, sons of kings, lads from the court or old slaves. Next these people are sent to the outskirts of the ombala, saying: ‘This family will construct here; that one, over there.’

The great onjango of the court

In this onjango there are stones (used as seats). Inside is the seat of the small Kesongo, who also performs the role of Kongengele (who carries the skull (a fleshless human head) and the ocindambala (axe), in case they go to war). The other seats are those of the Soma, the big Kesongo, Muekalia, Epalanga and Cinduli (a former slave who also has power). There are also other seats for those wishing to approach the king. If a different person sits on one of the reserved seats, he or she will be in trouble.

Offering service

Everyone who suffers in his or her family, whether slave or sorcerer,Footnote 7 seeks refuge with the Soma, placing himself at the latter's service and bowing before him.

Not only slaves offered to serve. The children of the country also did so, because some fathers, though begetting the child, do not look after them. The child ends up as though fatherless. And seeing that those who offer their service at the court fare well, eat well and have clothes to wear, they also volunteer their service to the king and their father no longer sees them.

Ritual of the king's harvest (beginning to eat the new food)

When the maize is ripe and people are already eating it, the king and most important elders will not yet taste it; they plan the correct day to eat the new food.

The king orders the lads of the court to look for someone to kill. After they have killed someone, they remove the innards (slicing off a part of all the members and organs of the body: liver, leg, heart, etc.). They mix these things with ox meat and ferment ocimbombo;Footnote 8 they eat and drink and thus the new food is tasted.

Some important elders have done this, but without killing people; they kill just a small pig or other small animal and eat it with the new food. They add: ‘The ritual is performed, since if it is not, there will be sickness.’

The Soma cannot eat alone. Thus, he does not usually eat what comes through the main entrance; he has to offer everything to the people who come until none is left. What passes through the small entrance is just for him and arrives late in the afternoon. Only Cilala, Muekalia, Epalanga and Somakesenge know about this. They pass on the food and they should be given a little.

In the court of the king

The path leading to the court on leaving the onjango is not a straight line. There are a few twists and turns before arriving at the etambo Footnote 9 of the court. It is very beautiful. Passing by this etambo there is a small entrance to the Soma's house.

In the Soma's house there are many atambo (small worship houses), since each king who governs constructs an etambo for his elders and cares for all of them in the same way, including those already there.

Each etambo has a Cipuku (a young woman responsible for sweeping and performing the worship). Each king who governs, on encountering these women, treats them like he takes care of the atambo, since they are like his wives.

Cipuku is the spiritFootnote 10 who brings revelations. If a woman receives many revelations, people say: ‘It is the spirit ocipuku. Our ancestors blessed her with the gift of revelation.’ They build her a small house and present her with offerings. This house is called etambo. Sometimes she incorporates [the spirit] and says ‘I am Sekulu So-and-So’ and makes recommendations to the village elders. If something is happening or about to happen, she immediately says what will occur. They have the habit of memorizing everything that the prophetess said. If she gives them a command, they follow it to the letter, instructing their children.

We know that since the ancient times elders have trusted greatly in Suku.Footnote 11 His name is never pronounced with little suffering or little peace. If someone is sick, they make prayers to the ancestors in the atambo. One can only call Suku's name if the person is dying. They say: ‘The ancestors are not responding; we call Suku who formed us and gave us life.’

In the king's court there is a large house (warehouse) for fabrics and gunpowder.

Next to the warehouse there is a large house where people are laid. Inside this house a drain has been dug that leads outside (like a gutter to drain water).

When a person dies, they take the body to this house, sit it carefully on a stool above the gutter and pour spirit over the corpse so that it dries more quickly. The liquid drains outside via the gutter. The gutter is well-built with stones; it looks like a burrow, so one cannot see that what drains out is disgusting. After the person dries, they bind a stick in his or her hand. When the liquid ceases to drain out, the person is removed from there and placed on the side along with the chair. This is done for everyone, meaning that the house becomes extremely full. The people are sat on the chairs with a stick in the hand as if they had not died. Taking care of this are two women who are close to the king and a woman who serves as a guide to them both. The name of the latter is Kaciłułu. This name applies to this kind of work because she is responsible for taking care of the iłułu.Footnote 12

Of these people laid, it is said: ‘They are the ones who protect the Soma from malefic attacks. If they pass the entrances of the hoes, they will not reach the king.’

Akokoto

When the king dies, a dance is performed on a mountain. In taking the body to the akokoto, they carry it up a slope. The kings are not buried in graves. When they enter with the body in the akokoto, placing it in the coffin, they call an elder who used to be a slave. The elders decide that this man, who really used to be a slave, should be freed and go to his village.Footnote 13 The elders call an older man to come and bury the king. On arrival, this man finds the king in the hands of the elders to be placed in the coffin. The older man unties the sorcery belt that the king wore wrapped around his body. Other people soon arrive and run with him. They give him the head of a cow with horns, pack his bags and send him back to his homeland. He can never again return to the village.

Muekalia

In the ombala, the name Muekalia signifies that he is closest to the king, since he is the one who enthrones him and who can also depose him if he proves not to be a good person. He has the rightFootnote 14 to instate the king who the people want. For this reason, in all the kingdoms, whether small or large, the name Muekalia exists.

The substitution of the kings

When the king dies or is deposed, the man who will replace him invites a quimbandeiro to remove all the things that form part of the sorcery of his predecessor. At the gate of hoes they place another hoe with another spell. At the spot where Ndumbila sits another person is sacrificed. Everything that refers to the sorcery of the predecessor has to be changed; nothing remains. Even the quimbandeiro has to be someone different. Only the tree located between the paths remains.

The substitute king will also arrive with his wives. It depends on the wishes of the king's women if they will return to their villages or remain in the ombala in the care of the new king. If the court elders perceive that a woman is good, one of them agrees to marry her. If among the Inakulu (old widows) they recognize that one of them is virtuous and loved by everyone, the court elders will tell the king that she will be Nasoma (Wife of the King) or Inakulu (older wife of the king). Those women without qualities will be told to leave.

Respecting the salute to the king

On approaching the king, he must be honoured (one kneels and bows, falling on the ground next to him). Afterwards they should salute the king, saying ‘He is the lion, he is the lion’ and applauding. The king then replies: ‘Akuku, akuku’ or ‘Kalunga, kalunga.’ Afterwards the person sits down and begins to speak.

The salute citing the lion signifies that the person saluting him respects him as the lion who devours people, implying that if the king wishes to devour him like a lion, he can do (if he wants to sell him or kill him, he can too).

Captain Teixeira da Silva

At this moment in time, our country was beginning to be invaded by whites. All the things that the kings did began to change. There would be a time when all the people and kings would be governed by white people, hence they would not allow us to do as we wished.

A certain Captain Teixeira da Silva was in Viye. So the war began and the Hona gathered to fight against Viye. After the Hona returned, perhaps he was scared of ending up alone. So he left there naked and arrived at the ombala of Bailundo. ÑałaFootnote 15 Ekuikui immediately greeted him warmly. He gave him trousers, a shirt, a coat and some family, as well as a small house to live in. In the yard of this house there was a flat stone where he would sit to warm in the sun. Afterwards he wrote his name on that stone like someone driving in a stake. He picked up a hammer and a nail and, little by little, carved the stone and wrote his name. At that time, when he did this, people said: ‘The whites aren't lazy. What is this for, it seems like a child's game?’ They did not know he was governing us. Even today this name persists; therefore, it did not disappear. It functioned as he wanted.

It was during the period when they were looking after him. When the dance was convoked, they said: ‘Come and dance.’ And he danced. And they invited him to everything they did, saying: ‘He should do everything that we do because he is ours now. He cannot be absent from anything we do, if not we expel him.’

When Captain Teixeira tired of staying in the ombala, he asked the king to give him some lads to try to live in the Katapi. The king agreed. He began to get better and sent messages to Benguela. Gradually the whites began to move away and transform into a government.Footnote 16 Even today this administrative post is called Katapi. As they gathered, they became many and launched a war against the Ovimbundu, burning down the ombala. Hence the Ovimbundu were defeated until today.

King Kalandula and Mutu's wars

In the kingdom of Kalandula there was no peace. This is when the war against the whites began with King Kalandula and his Epalanga, Mutu-Yakevela.

At this time the whites began to make the Ovimbundu suffer, using them as porters without paying them, lying about their wages and beating them.

On seeing the situation, Mutu, Cilala and everyone else lost their heads, since they had never seen anything like it. One day Mutu became indebted to a white man, who rowed with him and gave him a slap. Mutu left extremely agitated.

He fired some shots at the administrative post, on the whites who had built in Katapi. But he was expelled. He went to WambuFootnote 17 and again gathered some war forces. He was defeated by Njimbu, who had come from Esele with his fellow creditors.

The inauguration of the king

When the king who is governing dies, the elders come to an agreement to choose a new regent from among the sons, maternal nephews or grandchildren of the kings.

They meet at night in the house of the eldest among them, Muekalia. This group of people is called Vakalia. During the meeting at night, one of them says ‘I want so-and-so to be king’, and each of them expresses their opinion. After everyone has declared their preference, Muekalia, the leader of leaders, says ‘I have chosen so-and-so’ and everyone applauds. Whoever is chosen by Muekalia will govern.

After the assembly advises everyone that so-and-so will reign, the entire village stores ocimbombo. Everyone, great or small, comes to the ombala to watch the inauguration ceremony.

The tribunal

If someone has robbed or killed someone else, hurt someone with a stone or owed some good to another person and does not wish to pay, the owner of this good goes to the ombala to expose the person in order for the king to force them to pay for this good promptly.

When someone takes a question to the ombala, they establish the date when the matter will be judged. When this day arrives, all the king's elders and all the other people involved meet in the ocila (the place where judgments are made).

The Soma is the last. When everyone else is sitting, he enters the court calmly with his robes dragging on the ground, and everyone remains in complete silence. When he sits, all the people who came to participate in the trial greet him with much applause. After sitting, he says a few simple words. Only then does he ask what the trial is about, although he knows. The person in question repeats what he or she has already said. Once finished, the Soma has the final word. At the end of the trial, all the people who brought a question before the king hand over two large pigs, which are roasted and divided up so that everyone who went to watch the trial receives their share.

But the person found guilty by the tribunal pays for the other person's goods. If the payment is two oxen, the king keeps one and the owner the other.

The king's funeral

If the king becomes sick everyone becomes very sad. But if his sickness is long, Muekalia and other elders reach an agreement to put an end to his life.

They choose some men, go to the house where the king is sick and when there, enter, hold his head and twist his neck several times. They leave and return the next day to do the same. When the head falls off, they say: ‘The Soma died, the Soma died.’

Over all these days on which they twist the king's neck, if someone comes to visit, they simply say ‘The Soma is still sick’ until the day that the head comes away from the neck. They then say: ‘Messengers, spread out and announce the king's funeral.’ And they do so.

The festival of death (ohunguta)

During this period, if the king died, the entire country was afraid because many people left the ombala to capture people in all the countries.

This festival of death would go as far as Cisanji, abducting and assaulting people. It even reached Mbuluvulu in Viye, abducting people until the king was buried. They kill many oxen, drink a lot of spirit and fire many shots! And dance.

When the funeral ends, the reign of the next king begins.

Famine

When there is famine in the country, people become irritated with the king and say: ‘Your fire is sad.’ Perhaps he will be deposed from government or admonished; they will say that he has no reverence for the kings who reigned on his throne, those who have died and he replaced. So he casts various spells so that the following year, when people begin to grow their crops, there is an abundant harvest.

Whenever the country confronts turbulence, they remove the king from the throne and place someone else on it who brings food and other things that the people want.

Rain

If people sow their crops and the rain ceases to fall, they become very worried since they do not know what more to do.

So, the king unites all the elders of the country and all the people weed the tombs. In the ombala they go to the akokoto (the place where the kings and important elders of the ombala are buried) to weed the tombs and also to construct mausoleums.

These days are hard work. People play drums, dance and revere the dead kings and elders of the past (those who have died) in order for them to release the rains, since they are the ones causing the problem. The people kill oxen and goats, pouring their blood over the tombs. They also scatter spirit and ocimbombo on the tombs, saying: ‘So that those who are in the tombs also eat this meat and drink this spirit and the ocimbombo to cheer their hearts.’

And on these days the rain begins to form.

Cultivation

Here in the Umbundu country, agricultural work was more of a female responsibility.

Men tend to plant just a few tobacco orchards to take with them when they travel and buy food.

When the rainy season arrives, the women busy themselves with the crops. They wake early in the morning to fetch water from the river, put the pot on the fire, and make funge, which they send to the onjango for the men to eat. Women eat directly from the sieve, and while they eat, fetch seeds, a hoe and their basket and go to the plantation to tend their crops.

Men just stay in the village chatting in the onjango. The most intelligent go to the forests to make hives and assemble them so that when the bees arrive, they can enter to produce honey and wax. They then sell the latter produce and make a lot of money for their sustenance.

The powerFootnote 18 of women

Here among the Umbundu, women have much power, men little. Theirs is exaggerated.

When the cultivation season arrives, they have much work to do. If some women want to harvest a lot of maize, they go to the quimbandeiro to obtain some strong medicines.

When it gets dark, some women leave their husband in bed and go to make enchantments in the houses of others, so that if the latter try to breed livestock, the animals will simply sicken and die, or if they try to save money made on trips, they make little profit. But they make these enchantments late at night or early morning when everyone is deep asleep, and nobody awake.

The divinerFootnote 19

If there is a quimbandeiro in a family and he dies, someone from this family goes to a quimbandeiro in another country to receive the umbanda of the deceased and Cimbanda shows him all the medications in the forest, ranging from those that cure diverse diseases to those that kill people. But Cimbanda tells this person that when they return they should spend an entire year as a diviner; in the second year they should kill someone from their own family in order for their divinations to be successful and for people to accept everything that they say.

Caravan journeysFootnote 20

Since the ancient times, if people wish to leave on an excursion, they agree a month in the following year, saying: ‘We will set off that month.’ They then grow tobacco and save up salt and beads so that when they depart, they have a reserve to buy food on the journey.

The goods that they take are blankets, guns, gunpowder, pots, and sometimes tobacco, beads and salt. Those who have none of these things usually make deals so that when they make a profit, they walk around with cloths like rich people and traders.Footnote 21

Just before the caravan is about to leave, its guide goes to the quimbandeiro, who grates pieces of tree bark, mixes them with water and soil, and gives the concoction to the guide who wants to be the caravan leader, saying: ‘Drink it so that when you leave, the people you leave behind don't curse you, and your business in the land of the Ngangela goes very well.’

The slave

The slave is a person who was bought. Here there are many slaves. Some are slaves because their maternal uncle had many debts.

Some slaves are from the time when the traders would go to the Ngangela to buy many people. Some are slaves because when they are still with their family, while young, they do bad things and the family agrees that it would be better to sell the lad.

Slavery is painful. It is better to have a large injury than be subject to the will of a master. The slave must do whatever his master commands.

There are many cases in which a person was a slave, but the master recognizes that he is intelligent and nominates him as leader of the others. When the master dies, it is this person who will lead the family in his place: slaves, nobles, children of birth or nephews. He is the one they will call Sekulu.Footnote 22

When a noble person dies, their funeral turns into a festival. They play drums, dance, play, fire guns and kill oxen. With slaves, this is not the case. It is true that slavery is painful. It is preferable to have a large wound.