There are good reasons for mental health services to be concerned about violence. In 2004, the World Health Organization described violence as a major cause of mortality and morbidity, and identified it as an international public health problem (Reference Krug, Dahlberg and MercyKrug 2002). In the health context, violence excludes civil or international armed conflict, but refers to the health impact of violence between individuals and groups, in the home or on the street, both fatal and non-fatal. Violence not only causes physical damage and death, it is also a potent risk factor for future violence, in terms of repeat perpetration and sometimes raising the risk that victims will become perpetrators.

Regarding mental health service planning, exposure to and injury by violence causes mental distress and disability which can be long term. Such health effects have cost implications both directly, in terms of the treatment needs of victims and perpetrators, and indirectly, in terms of the associated costs of general medical service utilisation and of the criminal justice processes that respond to violence.

It is sometimes suggested that violence is not a medical problem but a universal and inevitable feature of human behaviour. However, the actuarial evidence is against this. In most Anglophone/European countries, violence is a comparatively rare form of criminal behaviour. In England and Wales, it constitutes only 20% of recorded crime, and rates of all forms of violence have been dropping over the past decade (Home Office 2009; Reference Smith, Flatley and ColemanSmith 2010). Homicide rates in England and Wales doubled between 1960 and 1980, but have been stable ever since, numbering about 600 annually (Reference Taylor and GunnTaylor 1999). If we assume that 40 million people are physically able to commit a homicide, a subgroup of only 600–700 looks highly statistically deviant.

We suggest that the criminal justice data indicate that violence is a comparatively rare human behaviour, but the combination of its rarity and its disproportionately damaging effects requires explanation that can drive interventions.

Risk factors for violence

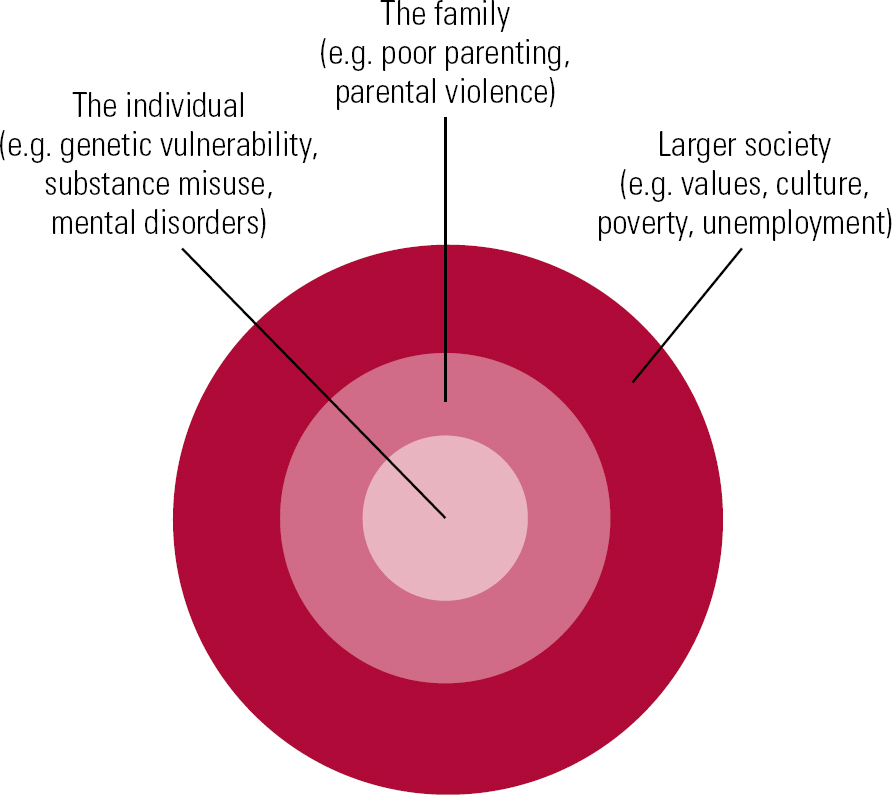

The World Health Organization (Reference Butchart, Phinney and CheckButchart 2004) report into violence suggested that an ecological model which incorporates a variety of influences holds most explanatory power (Reference BronfenbrennerBronfenbrenner 1977; Fig. 1). In this model, individual psychological risk factors (including mental illness and personality disorder) are likely to be small but significant risk factors for violence, and will need attention from mental health services. Risk assessment and intervention to reduce the risk of violence are key quality indicators for most mental health services providers, and an essential part of the care programme approach (Reference MadenMaden 2007).

FIG 1 Ecological model of violence.

There are other reasons why psychological approaches to understanding and changing violence-prone states of mind are important. First, the evidence about the nature of violence suggests that at least half of it arises in the context of a relationship between two people (Reference Smith, Flatley and ColemanSmith 2010). This is particularly true for children and infants under 1 year: infants are most at risk of being victims of homicide, and perpetrators are parents or in parental roles in 80% of such cases.

Second, severity of inflicted violence is affected by the relationship between perpetrator and victim; this appears to be the case for both sexual violence and homicide. Over 50% of homicides in England and Wales last year arose in the context of a quarrel, revenge or dispute between people who were well known to each other (Reference Smith, Flatley and ColemanSmith 2010), indicating that the perpetrator had thoughts and feelings about the victim in their mind before the violence began (i.e. they had a representation of the victim or their relationship with them in mind). Attention to the relationship, and the feelings/thoughts associated with it, might be an important way to reduce the risk of violence.

Finally, it is now well established that certain types of disordered mental state – paranoid mental states, combined with disinhibition and impaired reality-testing – increase the risk of violence. Other risky psychological attitudes include lack of empathy, dehumanising people, and cruel and derogatory attitudes to the vulnerable. Psychological interventions that operate on how individuals ‘see’ others in their mind, and how they make judgements about reality and risk, could be helpful to the subgroup of psychiatric service users who present a risk to others.

A complexity for forensic mental services (especially secure residential settings) is that they must treat not only for mental health restoration, but also for risk reduction and violence prevention (Reference Glorney, Perkins and AdsheadGlorney 2010). It is not enough that patients feel better, they must also behave better (Reference AdsheadAdshead 2000). Therapeutic interventions, whether pharmacological, occupational or psychological, need to address the patient's capacity to cruelty and violence, as this will have been the reason they were admitted in the first place.

Thinking of others: the social mind, empathy and mentalisation

Anthropological study of human evolution and psychological development indicates that, like other primates, we are social animals who live in groups; and that our neocortex volume is related to the nature and extent of social relationships we need for survival (Reference DunbarDunbar 2003). This expanded neocortex is the substrate for our ‘social’ mind: the capacity to assess others as potential allies, mates, peers or predators. Unlike the other great apes and primates with whom we share so much genetic material, humans have extensive capacities for self-awareness and reflection on that awareness, and the capacity to imagine the state of mind of others.

This capacity to have mind-in-mind is also known as mentalisation – an individual's ability to recognise and imagine their own internal mental states and those of others (including beliefs, intentions, emotions and motivations) and, more importantly, understand and interpret one's own and others' actions as meaningful on the basis of these states (Reference Allen, Fonagy and BatemanAllen 2008). Mentalisation includes a variety of meta-level operations of mind such as empathy, theory of mind, emotional recognition, metacognition and self-reflective function. It requires interpersonal abilities that are integral to a stable sense of self. It is not so much a capacity but a process which is going on in the mind at all times: it is about ‘reading’ other people's minds and also reflecting on one's own (known as self-reflective or reflective function; Reference Fonagy and TargetFonagy 1997).

An important theoretical development has been the explicit link between early attachment relationships and the mentalising process in the mind of the child (Reference FonagyFonagy 2003a,Reference Fonagy, Pfäfflin and Adsheadb). Secure attachment in childhood is associated with the development of enhanced mentalisation processes, which in turn contribute to the homeostatic regulation of negative affect and arousal regulation (Reference SchoreSchore 1996, Reference Schore2001; Reference Sarkar and AdsheadSarkar 2006). A person with limited or reduced mentalising processes will not be able to manage negative emotions such as normal anger, hatred and wishes to hurt. They are likely to become highly aroused very quickly and experience themselves as unable to think. Feelings of being overwhelmed with negative affects may lead to physical expressions of these affects, from shouting and damaging property, to self-harm and ultimately to harming others.

This escalating spectrum of acting out of negative affects may explain why it is unusual to find isolated acts of violence occurring de novo. Most people with histories of acts of violence have escalated from verbal abuse and property damage to self-harm or harm to others; and there is some evidence that those who self-harm have a small but real increased risk of acting violently, and vice versa. The concept of a spectrum of acting out behaviours (property → self → others) would also explain why national trends in suicide and homicide tend to be very similar (Reference GilliganGilligan 2011).

The mentalising process is essential to two other areas of mental function: self–other discrimination and self–other security. First, reflective function entails the capacity to distinguish one's own mind from that of another; it allows a thinker to see other minds as real, and makes and maintains the boundary between different internal worlds. People with poor reflective function (e.g. individuals with borderline personality disorder) find it difficult to distinguish between self-states and other states; instead, there is enmeshment between self and others which gives rise to severe anxiety (Reference Bender and SkodolBender 2007). Such blurring of self–other boundaries has been found to be associated with violence to others in the context of psychotic mental disorders (Reference Link, Stueve, Monahan and SteadmanLink 1994).

Second, reflective function enables a person to attach to others safely; it is crucial to being prosocial. As suggested above, it is an aspect of the social mind that evolved out of our identity as group animals and our need to communicate over time and place. Without the ability to ‘read’ other minds accurately, other group members may be identified as either ‘predator’ or ‘prey’, or (worse) something that oscillates between. There will be no opportunity to make attachment bonds to peers which allow groups to form that enhance safety and social function; lack of reflective function may result in social exclusion, which itself results in increased mortality and early death (Reference House, Landis and UmbersonHouse 1988).

A measure of reflective function has been developed on the basis of attachment narratives. (Reference Fonagy, Target and SteeleFonagy 1998). Individuals who have high levels of mentalising function are better able to process negative affects, so that they do not overwhelm the mind and stop thought. In contrast, those who have low mentalising function are overwhelmed by negative affects and unable to metabolise them effectively. The link between poor mentalising function and affect dysregulation has been made most clearly in relation to borderline personality disorder (Reference Bateman and FonagyBateman 2006; Reference Levy, Meehan and KellyLevy 2006). The characteristic ‘affect storms’ of borderline personality disorder are accompanied by cognitive distortions (often of parapsychotic intensity) and acts of violence (usually self-directed).

Violence as failure of mentalising: releasing the locks on violence

The psychological and psychiatric study of violence explores the contribution of the individual's internal psychological experience to risk. In this sense, an individual offender's psychological or psychiatric state is like the last number of a bicycle lock: acting as the final risk factor which, when combined with others, ‘unlocks’ the inhibitory mechanisms that prevent violence exploding from the internal to the external world (Reference BlairBlair 2003).

In this section we review the evidence that low levels of mentalising enhance the risk of violence. There are two principal ways to address this:

-

1 to look at levels of violence in people who may be expected to have poor reflective function owing to attachment insecurity; and

-

2 to measure reflective function in violent offenders.

Violence in people with insecure attachments who may be mentalising poorly

Understanding violence within a mentalising framework entails examining the association between early maladaptive attachment styles (Reference Shonk and CicchettiShonk 2001) and subsequent behavioural responses to negative interpersonal interactions (Reference Bateman and FonagyBateman 2008a). The attachment paradigm might be useful for relational violence in particular (Reference Pfäfflin and AdsheadPfäfflin 2004). The majority of victims of severe violence are related to the perpetrator by attachment relationships: partners, ex-partners, parents, friends or children (Reference Smith, Flatley and ColemanSmith 2010). Interestingly, a significant subgroup of forensic patients are admitted to secure care because of attacks on professional carers with whom they may have had a professional attachment (Reference AdsheadAdshead 1998).

Attachment systems are activated at times of distress, arousal and threat (Reference BowlbyBowlby 1960) and violent behaviours are known to be more likely at such times. Individuals with insecure attachments are known to have poor affect regulation (Reference SchoreSchore 2002), and acts of violence are usually described as being affectful or affectless (Reference MeloyMeloy 2006). Crime scene indicators often suggest either explosions of extreme, disorganised and disproportionate affect, or highly controlled violence (Reference Canter, Alison and AlisonCanter 2004). Such outbursts suggest a disastrous failure to mentalise negative affects such as shame, hatred, fear or anger in the context of interpersonal conflict and/or high negative expressed emotion (Reference GilliganGilligan 2002).

However, the evidence that insecure attachment alone is a highly influential risk factor for violence is limited. Insecure attachment is an expected finding in 40% of the community as a whole (Reference van Ijzendoorn and Bakermans-Kranenburgvan Ijzendoorn 2003) and is therefore too common to account causally for violence as a whole. Self-directed violence has been described in association with personality disorder, where insecurity of attachment is a feature of childhood history, especially borderline personality disorder where enmeshed attachment patterns are commonly found (Reference Levy, Meehan and WeberLevy 2005). However, only a minority of people with personality disorder, even antisocial personality disorder, are violent to others (Reference Duggan, Howard, McMurran and HowardDuggan 2009). In a recent study of attachment in prisoners, insecure attachment was not associated with convictions for violence, although anxious attachment was associated with intimate partner violence (Reference Hansen, Waage and EidHansen 2011).

Insecurity of attachment may only be a risk factor for violence in certain circumstances or under certain conditions. Disorganised attachment in childhood is associated with the development of more severe clinical psychiatric disorders (Reference van Ijzendoorn and Bakermans-Kranenburgvan Ijzendoorn 2003), although it has not yet been established that the severity of any psychiatric disorder is a risk factor for violence.

Maltreated children are at increased risk of developing conduct disorder, which in turn puts them at risk of antisocial behaviour in youth and early adulthood (Reference Kim-Cohen, Caspi and TaylorKim-Cohen 2006, Reference Kim-Cohen, Cicchetti and Rogosch2009): disorganised attachment may be the mediator, although this is also not established.

Studies of violence trajectories in youth suggest that there is a subgroup of children who show callous and unempathic attitudes from an early age, and later display violent behaviour (Reference Wootton, Frick and SheltonWootton 1997). However, it is still not clear whether the lack of the mentalising process is operative here or whether there is a relationship between disorganised attachment, poor mentalising and callous and unempathic attitudes.

Insecure attachment and failure of mentalising in violent populations

If failure of the mentalising process is relevant to violence commission, then we might expect to find evidence in violent offenders of either:

-

1 highly insecure attachment histories; or

-

2 low levels of reflective function.

There is now a considerable evidence base of studies that show higher levels of insecure attachment in violent offenders compared with community norms (see Reference Pfäfflin and AdsheadPfäfflin 2004 for review; Reference Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IjzendoornBakermans-Kranenburg 2009). In the general population, insecurity of attachment is found in 40% of the population, but in forensic settings, this is closer to 60–70% (Reference Frodi, Dernevik and SepaFrodi 2001; Reference Adshead, Pfäfflin and AdsheadAdshead 2004; Reference Levinson and FonagyLevinson 2004; Reference Bogaerts, Vanheule and DeclerqBogaerts 2005).

This level of insecure attachment is unsurprising, given the excess levels of childhood adversity and trauma in forensic populations, both in prison and secure psychiatric settings. Offenders in prison or forensic secure care are more likely to have been separated from their parents, severely physically maltreated or neglected, and put into Social Services' care before age 15 years than their non-offending community counterparts. Abuse and neglect are typically reported in 30% of most general populations internationally (Reference Kessler, Mclaughlin and Greif GreenKessler 2010), but rates of 60–70% are the norm in forensic settings (Reference CoidCoid 1992; Reference Heads, Taylor and LeeseHeads 1997; Reference Weeks and WidomWeeks 1998).

Types of insecure attachment

A number of types of insecure attachment may be relevant to poor mentalising (Box 1). Among these, type CC is a highly disorganised adult attachment pattern in which both enmeshed (E) and dismissing (D) attachment styles are mixed together in a chaotic way (Reference Hesse, Cassidy and ShaverHesse 2008). Type CC is commonly found in clinical populations (Reference Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IjzendoornBakermans-Kranenburg 2009). Individuals with CC attachment status may be intermittently in hostile, helpless, frightened or frightening states of mind (Reference Lyons-Ruth, Bronfman, Atwood, Solomon and GeorgeLyons-Ruth 1999; Reference Hesse and MainHesse 2000). In addition, individuals may have unresolved (U) attachment representations in relation to loss or trauma, which result in unpredictable and disturbing lapses of reasoning or thinking when reminded of the trauma. Unresolved traumatic affects (such as may be present in post-traumatic stress disorder) can cause brief and discrete failures of mentalisation (Reference George, Kaplan and MainGeorge 1985).

BOX 1 The most common forms of insecure attachment

-

• Enmeshed or preoccupied (E)

-

• Dismissing or avoidant (D)

-

• Cannot classify (CC)

The patterns of insecure attachment found in forensic populations are different from those in other clinical populations. Most studies of attachment in clinical populations find high levels of E and/or CC attachment, whereas studies of attachment in offenders typically find high levels of D attachment (Reference Adshead, Pfäfflin and AdsheadAdshead 2004: p. 152). This is a pattern of thinking about attachment relationships in which neediness and vulnerability are denied, disavowed or even derogated (Reference Hesse, Cassidy and ShaverHesse 2008). Dismissing attachment organisation may be relevant to the commission of violent acts that entail derogatory attitudes to neediness, dependence and pain; in fact, it may be difficult to commit such acts without such derogatory attitudes.

The other types of insecure attachment are less common in forensic settings than in other clinical groups. This may be an artefact of measurement or may reflect that measurement of attachment is taking place in a setting where people are frightened and defensive, and reluctant to show vulnerability. We might hypothesise that the CC category would be more common in forensic psychiatric populations who are mentally unwell as well as violently antisocial, but this has not yet been shown to be the case.

Self-reflective function

If violence is related to poor mentalising capacity, then we should expect to find low levels of mentalising function in violent offenders as measured by self-reflective function. However, only one study has specifically looked at reflective function in violent offenders. Reference Levinson and FonagyLevinson & Fonagy (2004) measured reflective function in a sample of men imprisoned for a variety of offences and found that violent offenders had lower levels of reflective function than non-violent offenders. Reference Bateman and FonagyBateman & Fonagy (2008b) have also found low levels of reflective function in individuals with self-directed violence and they argue that reductions in such behaviour are mediated by therapies that improve mentalisation and reflective function, such as mentalisation-based treatment (MBT) and transference-focused therapy (Reference Levy, Meehan and KellyLevy 2006). However, the relationship between self-directed violence (in terms of self-harm) and other directed violence is not clear: Reference GilliganGilligan's work (2011) finds a link between completed suicide and homicide rates, not self-harming behaviours, that are the focus of most treatment interventions. In addition, the Levinson & Fonagy study has yet to be replicated.

Linking mentalisation failure and violence

The attachment and mentalisation model of mind would suggest that people with highly disorganised attachment systems may be at risk of failing to mentalise when their attachment histories are triggered. These difficulties are essentially a diminished view of the self in relation to others. Feelings of shame could activate this temporary state of mind. Shame has been associated with antisocial and violent behaviours and might have some explanatory value in relation to fragile self-concepts and humiliation (Reference GilliganGilligan 2002). Shame has been conceptualised in evolutionary terms as relating to threatened perceptions of the self in the social hierarchy (Reference Gilbert and IrelandGilbert 2005).

High v. low affect

The question of affect dysregulation and violence is complicated. Violent offenders may be divided into a high-affect, impulsive and hyperaroused group on the one hand, and a low-affect, hypoaroused and unemotional group on the other (Reference MeloyMeloy 2006). The high-affect group resemble patients with borderline personality disorder who repeatedly harm themselves, leading Reference Bateman and FonagyBateman & Fonagy (2009) to propose that a subgroup of people with antisocial personality disorder resemble people with borderline personality disorder, who can oscillate between reasonable reflective function and temporary losses of mentalising function with consequent fragmented self-experience and frightening affect storms. Such unstable oscillations of mental state are characteristic of disorganised attachment processes (Reference van Ijzendoorn and Bakermans-Kranenburgvan Ijzendoorn 2003), and in such a state it may be impossible to make coherent (and safe) judgements about other people's minds.

Conversely, the low-affect group seem to have little concern for anyone's feelings, including their own. Indeed, there is some evidence that some violent offenders are satisfied by seeing fear or distress in others, and experience a sense of mastery and control in the presence of others' distress. Reference MeloyMeloy (2006) describes this group as predatory; and this group do seem to function socially as if they were hunters and other people were (literally) ‘fair game’. Specifically, this group of violent offenders also appear to experience contempt and derogation for vulnerability, neediness and distress; even if this does reflect unconscious projection of vulnerability, it reflects a conscious wish to hurt and control. Such states of mind are often seen as characteristics of psychopathy: a specific form of personality disorder in which meanness and cruelty to vulnerable others is a key factor (Reference Patrick, Fowler and KruegerPatrick 2009). It is possible to see a link between the dismissing derogating attachment style (which is found in only a small subgroup of the population) and the subgroup offviolent offenders who are specifically cruel and humiliating to people who are vulnerable and distressed, and who score highly on psychopathy measures (Reference Frodi, Dernevik and SepaFrodi 2001).

Not only is some violence both predatory and highly controlled: some types of violence and cruelty to others suggest that the perpetrator's reflective function in terms of assessing the victim's intentions is particularly high. Reflective function may be high when empathy is low: studies of military atrocities suggest that there is no necessary connection between these two factors (Reference BurleighBurleigh 1995; Reference BrowningBrowning 2001). It might be argued that in these men and women, the affective disturbance is unconscious but still present: what is consciously detectable is a disavowal of affect, characteristic of dismissing attachment systems (Reference BowlbyBowlby 1960).

A further subgroup of individuals becomes aroused and affectful only when they see others' distress; this arousal may become sexualised. This subgroup may have something in common with people who self-harm who describe emptiness, numbness and affectlessness until they harm themselves.

Failure of empathy and reduced theory of mind

The link between mentalising and violence is also complex because some accounts of mentalising include psychological capacities such as empathy and the capacity to conceive of other minds (Reference Choi-Kain and GundersonChoi-Kain 2008). Failure of empathy is a key feature of violent offending (Reference Joliffe and FarringdonJoliffe 2006), so prima facie this would indicate a failure of mentalising capacity. However, studies of empathy in offenders have mixed findings in terms of lack of empathy (Reference Joliffe and FarringdonJoliffe 2006): not all violent offenders demonstrate lack of empathy and some offenders may actually score highly on empathy.

There has been similar theoretical interest in whether violent offenders show reduced theory of mind capacity (as in autism); the hypothesis being that people with theory of mind deficits would not recognise or be disturbed by others' distress. The evidence here again is conflicting: some offenders do show theory of mind deficits but others do not. Even offenders who score highly on psychopathy measures (and who are therefore at increased risk of acting violently) do not necessarily show theory of mind deficits (Reference Richell, Mitchell and NewmanRichell 2003; Reference Dolan and FullamDolan 2004).

The two types of violence (high-affect and low-affect) mirror the current discussions about two different neuronal systems underlying empathy and theory of mind. Reference BlairBlair (2005) distinguishes emotional empathy and cognitive empathy, with the latter being akin to theory of mind; and there is evidence that there are two different systems involving the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex that underpin empathic responses (Reference Shamay-Tsoory, Aharon-Peretz and PerryShamay-Tsoory 2009, Reference Shamay-Tsoory, Harari and Aharon Peretz2010).

Another helpful contribution, drawing on social cognitive neuroscience, is Reference LiebermanLieberman's (2007) distinction between internally and externally focused aspects of theory of mind. Internally focused processes are activated by mentalising aspects of the self and others' thoughts, feelings and experience – their ‘interior world’. On the other hand, the external focus is on physical and visible features; the non-mentalising aspects of theory of mind. In reviewing the basis for a mentalisation-based approach for people with borderline personality disorder, Reference Fonagy and LuytenFonagy & Luyten (2009) refer to this group as having difficulty in tasks that require a direct focus on mental interiors, while being adept at understanding external characteristics. The same distinction may apply to people with affectful violence.

Psychosis

The failure-to-mentalise model of violence also needs to explain the contribution of psychosis to violence-prone mental states. Psychosis increases the risk of violence in a number of ways: by simple disinhibition, failure of good-quality judgement when reality is distorted, or rational response to perceived (but irrational) threat (Reference Link, Stueve, Monahan and SteadmanLink 1994). Severe affective dysregulation may lead to psychotic states (and vice versa), and failures of metacognition are well documented in psychotic states (Reference Dimaggio, Lysaker and CarcioneDimaggio 2008). This function is distinct from mentalisation, and although it is tempting to assume that psychosis reduces mentalising function, this has not yet been demonstrated.

Improving mentalisation with violent individuals: a pilot project in a high secure hospital

The effectiveness of MBT in borderline personality disorder is of therapeutic significance to those treating violent states of mind, especially in terms of reduction of impulsive violence. The overall structure of MBT provides a space in which the objective is to think about how thoughts and feelings dictate actions and to identify where errors in this process occur that result in problematic reactions. In research trials, MBT techniques that aim to improve reflective function have been shown to decrease affect storms, improve abilities to self-reflect and reduce self-harming behaviours, improvements maintained over the longer term (Reference Levy, Meehan and KellyLevy 2006; Reference Bateman and FonagyBateman 2008a,Reference Bateman and Fonagyb).

We set up a pilot MBT group to test its acceptability to patients and to see whether it is possible to replicate the technical format of MBT in long-stay residential secure care. We selected as potential group members men who had struggled with high levels of episodic violence throughout their lives, including within the hospital. We also selected men who had a variety of severe personality psychopathology: this is the norm in specialist and high secure settings (Reference Blackburn, Logan and DonnellyBlackburn 2003; Reference Yang, Coid and TyrerYang 2010) (Table 1). We made it clear to participants that this was a pilot and that its aim was to increase their capacity to manage negative affects and to improve reality-testing and perspective-taking in their day-to-day lives. We used a variety of interventions aimed at improving mentalising function (Reference Allen, Fonagy and BatemanAllen 2008), including psychoeducational sessions and film clips as well as reflective sessions.

TABLE 1 Mentalisation-based treatment pilot study attenders in a high secure hospital

Nine patients were referred for the first group; one patient declined to participate during the assessment process and two dropped out of the group at a later stage. In terms of diagnoses, four had a primary diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia, but comorbid personality dysfunction was also present in these men, although they did not meet full criteria for diagnosis. Similarly, the men with primary personality disorder diagnoses also had histories of psychosis. Such diagnostic comorbidity is typical of high secure hospital patients (Reference Blackburn, Logan and DonnellyBlackburn 2003).

Forty-eight group sessions were conducted between January 2008 and March 2009. There was full attendance at 31 of these meetings, with reasons for non-attendance including feeling unwell or competing appointments (e.g. visitors to the hospital).

Three trained facilitators were present at the sessions most weeks, but on occasion the group ran with two facilitators. The range of techniques within the MBT literature aimed at improving mentalising function (Reference Allen, Fonagy and BatemanAllen 2008), including introductory psychoeducational sessions to prepare participants to get the most out of the group meetings and reflective individual sessions. We rated the adherence of the group therapists to the MBT model using guidance published by Bateman & Fonagy (2004).

Preliminary findings

The pilot project showed the importance of the group process for improving mentalising. Group membership and the group process makes multiple perspective-taking inevitable as a psychological exercise. Group activity does not stimulate the attachment system in the same way as one-to-one sessions, especially for those individuals who had suffered abuse by caregivers. Multiple mirroring is possible, which may be relevant to empathic function through imitation and the stimulation of mirror neurons (Reference GalleseGallese 2001, Reference Gallese, Keysers and Rizzolatti2004). In the forensic context, group work also offered the possibility of belonging to something again and connecting to others – of being ‘social’. Such a view fits with other accounts of the importance of group work with offenders (Reference Marshall and BurtonMarshall 2010).

Self-report and behavioural data-based measures were collated at 12 and 18 months (effectively mid- and post-group) and followed up at 6 months post-group. Three participants reported improvements in mindfulness, scoring in a non-clinical normative range of functioning post-group. However, no significant change was reported.

We noted more functional defence style (as measured on the Defense Style Questionnaire: Reference Andrew, Singh and BondAndrew 1993) in one participant, and clinically and reliably significant change across all scales of the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP-64; Reference Horowitz, Alden and WigginsHorowitz 2000) in another. Where any improvement in interpersonal problem-solving was endorsed, this was maintained at follow-up and beyond the group. The majority of the group graduates reported significant improvements overall in relation to interpersonal problems.

Interpersonal relationships are a risk factor for violent incidents taking place within the hospital so we looked for any changes in incident data in terms of behaviour within the hospital. There was a low base rate of within-hospital incidents for this pilot group, probably due to careful selection from the early stages of referral by the clinical teams. No incidents were reported for three of the six participants. However, one patient was involved in an incident in which he directed physical violence against a fellow patient. It was possible to discuss this incident in the group session and explore the process of mentalising and its relationship to the use of aggression – perhaps an example of the direct portability and use of the model within the forensic context.

Two men dropped out of the group, but the rest group completed the year-long programme. At the time of writing, all the men have moved to a pre- discharge care pathway, including those who had been most violent most often. We did not specifically measure reflective function, so we cannot say whether improved mentalising has contributed to improved function in the hospital. It may be that, for individuals who struggle with so much psychological disability, any intervention that takes thinking seriously and encourages self-reflection (not just learning) will produce behavioural results.

Implications and future directions

In summary, results are inconclusive and questions remain about the role of mentalisation failure as a risk factor for violence. It may be relevant for only a subgroup of violent offenders, i.e. those with high affectivity and impulsivity (e.g. borderline personality disorder). One may therefore imagine that a typical individual will be a man who has been socially isolated, misusing substances and antisocial from late childhood. Such a man will almost certainly struggle to manage negative affects and is likely to be diagnosed with borderline personality traits. If he is psychologically ‘threatened’ with a perceived loss, he will be overwhelmed with feeling and may fail to mentalise. This loss of mentalising capacity will act as the final ‘number’ in the internal locking system and violence can then erupt. Once the affect storm is over, the offender patient may feel and behave calmly, and may only be violent again when the particular combination of circumstances is activated.

For this group of violent offenders, there would seem to be sufficient evidence to be offering mentalisation-based interventions, ideally in the form of controlled treatment trials. However, there still remains the puzzle of how best to intervene with violent men and women who seem to have high levels of mentalising function. The terrible and tragic case of Anders Breivik, an apparently normal young man who killed 77 people in Norway, makes the point of how urgently we need to find ways of understanding and managing cruel and unusual states of mind.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Mentalising does not include:

-

a organisation of information

-

b empathy

-

c theory of mind

-

d self-reflective function

-

e perspective-taking.

-

-

2 Mentalising function has been shown to be reduced in:

-

a schizophrenia

-

b bipolar disorder

-

c dementia

-

d borderline personality disorder

-

e conduct disorder.

-

-

3 In England and Wales, violence:

-

a is a rare form of criminality

-

b has been rising steadily year on year

-

c is the same as aggression

-

d is causally associated with antisocial personality disorder

-

e is common in men.

-

-

4 Mentalisation failures:

-

a are compatible with normal psychological function

-

b are always found in violent offenders

-

c cause attacks on self and others

-

d are unrelated to psychotic disorders

-

e are unrelated to mood disorders.

-

-

5 Mentalising function:

-

a can be measured using self-reflective function measures

-

b is improved only by mentalisation-based treatment (MBT)

-

c cannot be changed

-

d is a capacity made up of static factors

-

e does not change over the life-cycle.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | a | 2 | d | 3 | a | 4 | a | 5 | a |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.