What is a law report? Why should a psychiatrist want to look at one? How do you locate them? How do you make sense of them?

This article sets out to answer these questions and to give examples of key law reports which, whether we are aware of it or not, have had decisive effects on psychiatric practice. This is a guide for doctors, not lawyers, although the material in it will be very familiar to lawyers working in medical law. It is mainly relevant to the four countries of the UK, specifically England and Wales, although the principles will be similar elsewhere, particularly in commonwealth countries.

The work of lawyers is largely about resolving disputes or setting up agreements in advance in such a way that future disputes are minimised. A useful way to get right inside this process is to examine a court judgment. Anyone studying law is fortunate that most important legal judgments are published, so that the exact process of judicial reasoning can be followed in every detail. An important reason for judgments to be published is that courts are bound by judicial precedent, that is, a given court will be bound by the decisions of a higher court in a previous case that was similar in relevant ways. The rule of precedent is important in law to ensure that decisions are consistent with each other. So far as possible, the operation of the law should be predictable, rather than allowing arbitrary decisions.

The legal system in the UK

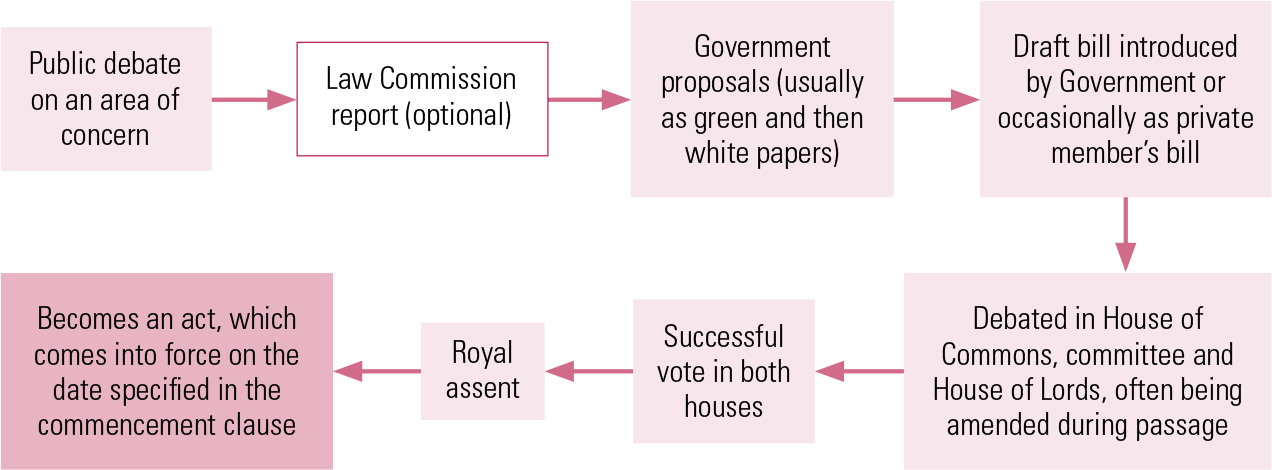

The UK, along with most commonwealth countries and the USA has a common law system based on statutes (acts of Parliament) and cases, which are argued in an adversarial way in court. Most continental countries have a different system known as civil law, which is based on a code. The creation of new laws in the UK usually starts with public debate, often in areas identified by the Law Commission as being in need of reform. The government may publish first a green consultation paper, then a white paper, following which a draft bill is introduced into Parliament. In Parliament, a bill must pass through both the House of Commons and the House of Lords and be considered in detail in committee (Fig. 1). Amendments are often tabled, so that the bill may have to pass repeatedly through each house.

FIG 1 How laws are passed in England and Wales.

Some acts of Parliament set out only a framework and delegate powers to draw up secondary legislation detailing how the principles in the act should be put into practice. In many cases, the Secretary of State is given powers to prepare statutory instruments, codes or regulations. Changing an act of Parliament takes a great deal of time, while introducing new statutory instruments, which are still binding, is much more straightforward. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), for example, was established by a statutory instrument. In the Mental Health Act 1983, the list of treatments differing in requirements for consent described in sections 57, 58 and 58A can be varied by the Secretary of State, who also prepares the Code of Practice. For example, the English Regulations 27(1) specify ‘the surgical implantation of hormones for the purpose of reducing male sex drive’ as a form of treatment to which section 57 applies. In R v Mental Health Act Commission Ex p. X (1988) the court found that the term ‘hormones’ included synthetically produced hormones, but not hormone analogues, and so the use of goserelin did not fall within this section.

Precedent and the court system in England and Wales

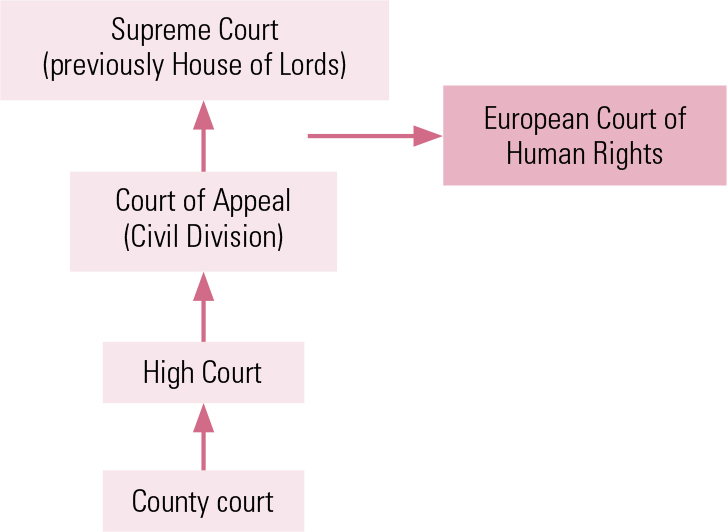

Courts in England and Wales

The courts apply acts of Parliament to cases brought before them. There is a hierarchy of courts (Fig. 2) in which previous relevant decisions of a higher court are binding on lower courts and usually on the same court (this is the rule of precedent). In England and Wales, civil cases normally start in the county court, although some cases are taken straight to the High Court. The Court of Protection, which deals with the affairs of people who lack capacity, functions as part of the High Court and may hear cases directly. In the event of an appeal, the case is referred up to the next highest court.

FIG 2 The civil court system in England and Wales.

European and UK law

In cases that engage human rights, once the case has been taken as far as it can through the UK courts it may be possible to take it to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, on the basis of an alleged breach of the 1950 European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

Under the Human Rights Act 1998, English courts must try to interpret English law to be in accordance with the Convention and where this is not possible they may issue a declaration of incompatibility, in essence declaring that English law cannot be interpreted in a way consistent with the Convention. This is what happened in the Bournewood case (see below) and the result was that the Government changed the law to bring it into line with the European Convention, which they did by using the Mental Health Act 2007 to amend the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (Schedules A1 and 1A, which deal with deprivation of liberty).

Precedent

Even with the rule of precedent there is great scope to argue about whether a previous case was sufficiently similar to be binding on the present case. The part of a case that is binding (the legal principle at its heart) is known as the ratio decidendi, whereas statements made by the judge that are not part of the key reasoning are called obiter dicta and these are not binding (although they may be persuasive). Earlier cases are almost always followed, unless the present case can be distinguished from them in some important way. Higher courts can overrule decisions of lower courts. Ultimately, the judge(s) is the arbiter of whether an earlier case is binding. Most key cases in medical law are heard without a jury.

What is a law report?

Ninety-five per cent of judgments handed down in court are not published. Most cases in England and Wales are now recorded, but the recordings are generally not transcribed and rarely see the light of day. If there is some legitimate reason to obtain a transcript, an application can be made to the court and a fee will be payable.

A small proportion of cases, particularly of the more significant cases in the higher courts, is published in one form or another. A case may be published either as just the judgment (the ‘neutral citation’) or as a law report. There are several series of published law reports, which start with a headnote (a summary of the main issues and findings in a case). This is followed by a transcription of the full judgment. The judge usually begins by summarising the facts of the case, the findings of lower courts in the matter if the case is being appealed, the legal arguments put on both sides (which will be based on relevant statute law and previous cases) and the reasons for preferring one argument over another, leading to the finding. In a simple case, this may be just a few pages; in a complex case, it can be more than 100 pages. The same case may be published in different series of law reports or on its own as the full judgment but without a headnote. Newspapers, journals and websites may also publish summaries or discussions of important cases.

High Court judges are known as ‘Surname J’ or ‘Mr/Mrs Justice Surname’, whereas Court of Appeal or Supreme Court judges are referred to as ‘Surname LJ’ or ‘Lord/Lady Justice Surname’.

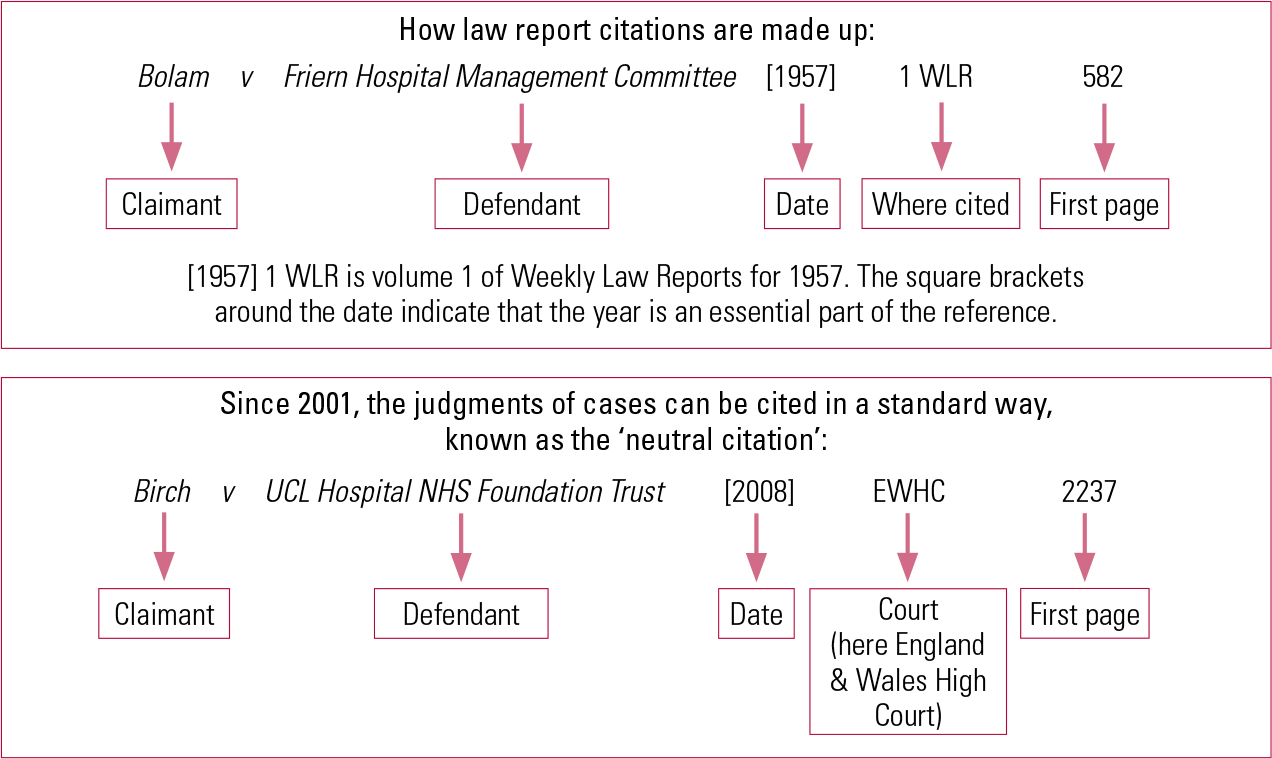

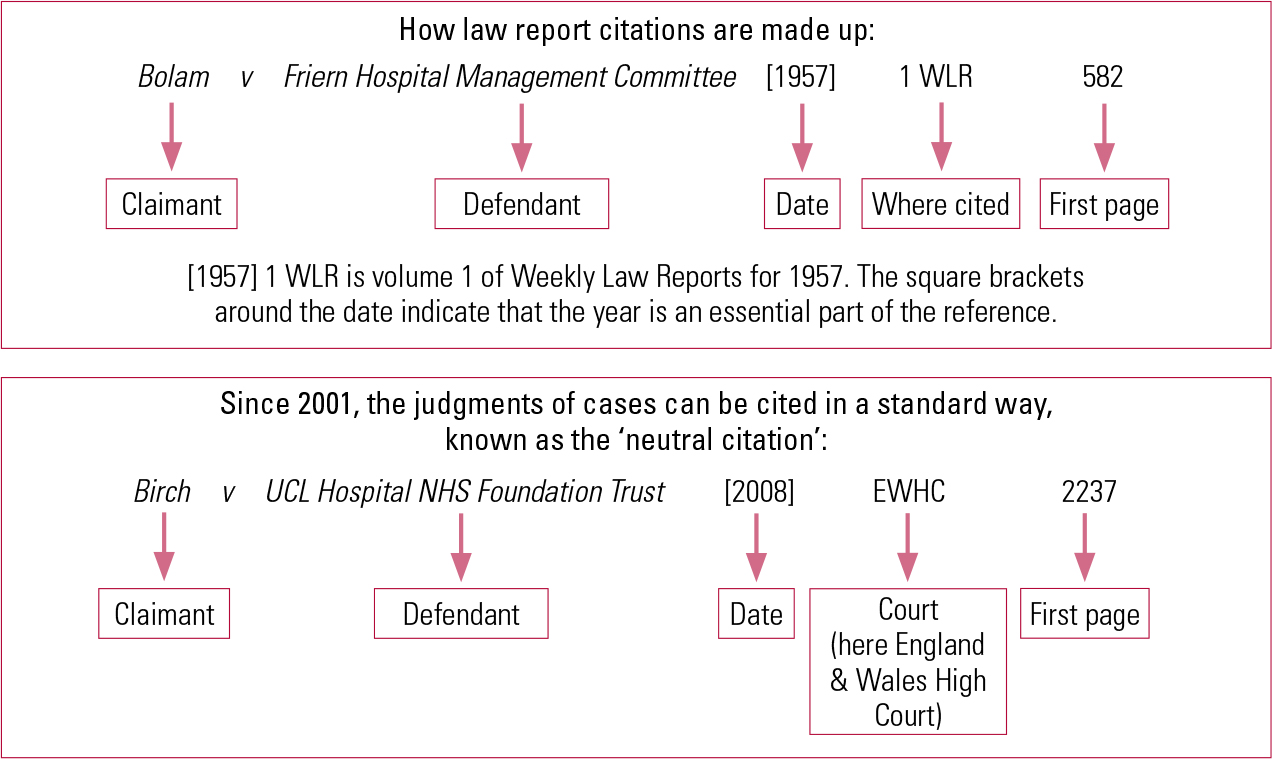

Figure 3 explains how cases are cited. Cases published in a series of law reports are cited according to the name of the parties, the year, the name of the series of reports and the first page. In addition, the uniform citation style described in Fig. 3 has been available since 2001. It is known as the neutral citation and refers to the freely available text of the judgment without any headnote. All of the sources will have the same text of the judgment itself, but law reports may provide different headnotes. As in medicine, there are different styles for referencing journal articles and other material. The nearest there is to a common standard, although it is far from universal, is the Oxford Standard for Citation of Legal Authorities (OSCOLA) system (Box 1). Abbreviations of journals are widely used, but there is no standard way of abbreviating journal titles, so the same journal may be abbreviated in many different ways and a given abbreviation may refer to several different journals.

FIG 3 How case citations work.

BOX 1 Useful websites

-

• BAILII contains key judgments back to 1996, as well as some earlier ones. It also has the full text of UK and Ireland legislation: www.bailii.org

-

• The Parliament website has a wealth of material on how Parliament works, including information on new legislation currently going through Parliament: www.parliament.uk

-

• HM Courts & Tribunals Service maintains a website giving recent judgments: www.hmcourts-service.gov.uk

-

• The full text of all UK legislation, both as enacted and as amended, together with secondary legislation such as statutory instruments, is at www.legislation.gov.uk

-

• Much useful health-related material is on the Department of Health website at www.dh.gov.uk

-

• The Law Commission reports on areas of law judged to be in need of reform and makes proposals for changes: www.lawcom.gov.uk

-

• For links to European judgments and the text of the European Convention on Human Rights, see www.echr.coe.int/echr/Homepage_EN

-

• A useful subscription website providing detailed regular mental health law updates with an associated Yahoo news group is at www.davesheppard.co.uk (Your hospital may already subscribe to this. Check with your Mental Health Act administrator or approved mental health professional.)

-

• Mental Health Law Online (www.mentalhealthlaw.co.uk) is a very useful website that offers free regular updates and a CPD service

-

• Details of the OSCOLA system of legal citation are at www.law.ox.ac.uk/publications/oscola.php

-

• A short tutorial on how to cite cases in the OSCOLA system is at https://ilrb.cf.ac.uk/citingreferences/oscola/tutorial/index.html

-

• A fairly comprehensive list of legal abbreviations is at www.legalabbrevs.cardiff.ac.uk

There may also be further citations, indicating that the case has been published in several different places. Lawyers consider some series of law reports to be more reliable than others.

Some family law cases (this often applies to psychiatric cases) use initials rather than full names of individuals in the title. If the case is brought on behalf of someone (e.g. an incapacitated adult) it may have a title such as ‘Re C (Adult: Refusal of Treatment)’. European cases use a different system (e.g. see the citation for the Bournewood case in the European Court, below).

How do you find a law report?

Finding judgments and citations

Since 2001, most judgments of the higher courts of the UK and Ireland have been published on the British and Irish Legal Information Institute (BAILII) website, a freely accessible online source (Box 1). BAILII also contains many key judgments back to 1996, along with citations, as well as the full text of UK and Ireland legislation. However, legislation is often amended, so it is important to make sure that you are looking at the current version.

Finding law reports

For earlier cases, and to read law reports, it may be necessary to search one of the legal databases such as Westlaw or Lexis. These are subscription-only, although some readers may have access through university resources. They can be searched by subject as well as case. Alternatively, law reports are published as bound volumes, which can be found in a law library. Legal textbooks and journals provide good accounts of cases and several textbooks include extracts from key judgments and other material (Box 2). Many newspapers and online services also report new cases: The Times law reports are well known. There are a number of internet sites that provide regular updates on areas of law, some of which require a paid subscription. The Mental Health Act administrator of psychiatric hospitals may know if the hospital subscribes to such a service, which may be made available to hospital staff.

BOX 2 Related reading

Clinch P (2001) Using a Law Library: A Student’s Guide to Legal Research Skills (2nd edn). Blackstone Press.

Elliott C, Quinn F (2010) English Legal System (11th edn). Pearson Education.

Gostin L, Bartlett P, Fennell P, et al (2010) Principles of Mental Health Law and Policy. Oxford University Press.

Hardy S (2001) Studying Law on the Internet. Internet Handbooks.

Herring J (2010) Medical Law and Ethics. Oxford University Press.

Holland JA, Webb JS (2006) Learning Legal Rules: A Students’ Guide to Legal Method and Reasoning. Oxford University Press.

Jackson E (2010) Medical Law: Text, Cases and Material (2nd edn). Oxford University Press.

Jones R (2010) Mental Capacity Act Manual (4th edn). Sweet and Maxwell.

Jones R (2010) Mental Health Act Manual (13th edn). Sweet and Maxwell.

The two manuals by Jones give very detailed commentary on these two acts, with many references to case law relevant to psychiatrists.

Some key cases

What is valid consent?

There is much case law on consent, although consent is not directly the subject of statute law. The Mental Capacity Act 2005 gives a definition of capacity, but does not define consent. The three cases below pre-date the Act, but are still relevant in determining how the concept of capacity should be applied. When people refer to ‘the law’, this usually means the combination of statute law (acts of Parliament, together with all the secondary legislation that is related to it) and case law. In some areas of law, statutes exist and are very specific (e.g. the Mental Health Act), whereas in others, courts rely on case law, as in the first example below.

Re C (Adult: Refusal of Treatment) [1994] 1 WLR 290

C, who had paranoid schizophrenia, was a patient at Broadmoor Hospital. He had a gangrenous leg and the surgeon was of the view that if it was not amputated he was likely to die. C sought an injunction to prevent the hospital from operating without his consent, saying that he would rather die with two feet than live with one. The judge in the Family Division of the High Court, Thorpe J, said:

‘I consider helpful Dr Eastman’s analysis of the decision-making process into three stages: first, comprehending and retaining treatment information, second, believing it and, third, weighing it in the balance to arrive at choice […] I am completely satisfied that the presumption that C. has the right of self-determination has not been displaced. Although his general capacity is impaired by schizophrenia, it has not been established that he does not sufficiently understand the nature, purpose and effects of the treatment he refuses. Indeed, I am satisfied that he has understood and retained the relevant treatment information, that in his own way he believes it, and that in the same fashion he has arrived at a clear choice.’

This case was decided 11 years before the Mental Capacity Act and itself relied on earlier judgments. Although it was heard in the High Court, the test of capacity in the case was approved in a later case in the Court of Appeal ( Re MB (An Adult: Medical Treatment) [1997] 2 FLR 426). Although the Act retains the framework of an assumption of capacity until proved otherwise, with an analysis of the steps in decision-making, the second step (of believing the treatment information) has not been retained (neither was it retained as a separate explicit step in Re MB). However, until the Act came into force, the analysis set out in this case and in Re MB provided the definitive legal test of capacity to make medical treatment decisions.

As cases on capacity are usually heard in the civil courts, the civil standard of proof applies, that is ‘on the balance of probabilities’, rather than the higher criminal standard of ‘beyond reasonable doubt’.

Re T (Adult: Refusal of Treatment) [1993] Fam 95 (CA)

Miss T was not herself a Jehovah’s Witness, but had been brought up until the age of 18 by her mother, who was one. She was 34 weeks pregnant, was injured in a road accident and had developed pneumonia. There was a need for Caesarean section. After a visit from her mother and having been given pethidine for pain, she signed forms consenting to the operation but refused consent to a blood transfusion. The baby was stillborn and Miss T had to be transferred to the intensive therapy unit with a lung abscess, too ill to give further consent. Her father sought a declaration that it would be lawful to give her a blood transfusion. An urgent decision of the High Court accepted her initial consent as valid, but found that it could not be established that her initial refusal of transfusion had been properly informed (since she had not been informed that she might die without it), neither was it clear that it extended to the new serious situation. So, the court held that she could be given a transfusion in her best interests and this was upheld in the Court of Appeal.

This judgment is remarkable for the clarity with which the judge argues the case, but also the urgency under which the decision had to be made. One of the hearings took place at the judge’s lodgings at 23:30 h, with the judge taking evidence from the doctor by telephone as the clinical situation unfolded. Two days later, the patient had become much more seriously ill and it was clear that she was likely to die unless the court issued a declaration that her previous refusal of blood transfusions was no longer valid. Lord Donaldson’s judgment conveys the difficulty that he had struggling to put the complex issues of evidence and legal principle together (‘I confess to having agonised all night to reach my conclusions’). One of the doctors involved made his job more difficult by changing his evidence between the late-night phone call and the full hearing 2 days later. Despite the judge’s implied criticism of the mother, who, ‘although a party to the proceedings, has never seen fit to give evidence’, he avoids taking the route of arguing that Miss T’s refusal was invalid because it was given under the influence of her mother. He instead devotes more than two pages to a detailed analysis of the evidence, explaining why he finds some parts more persuasive than others, concluding that although her initial refusal was valid, it did not cover the emergency ‘which was outside her contemplation and the contemplation of others at the time she expressed her opposition to a blood transfusion’. One is perhaps rarely so caught up in the human interest of a case, argued so clearly yet so compassionately.

Chester v Afshar [2004] UKHL 41

Courts have increasingly recognised the importance of autonomy, the right of patients to choose whether or not to accept treatment. Ms Chester consulted a surgeon, Mr Afshar, about her painful back. He recommended surgery but failed to warn her of the small risk of nerve damage. She agreed to the surgery, but the damage materialised and she was partially paralysed. She sued him, not for any technical shortcoming in the surgery, but for having failed to warn her of the risk. She argued that if he had told her, she would have sought a second opinion. Although in all likelihood she would have accepted the operation, it would have taken place at a later time and the risk might not have materialised on that occasion. By a majority, the House of Lords found in her favour. At first, this seems a perplexing judgment, possibly contrary to many people’s sense of natural justice, as Ms Chester admitted that she would have accepted the operation in any case. However, commentators have explained that an effect of the judgment is to underline the great importance that courts attach to providing information to patients to enable them to make informed decisions.

Testamentary capacity

Banks v Goodfellow (1869–70) LR 5 QB 549

John Banks had made a will in favour of his niece, but it was contested by the son of his half-brother, another John Banks, on the grounds that he had at times been confined with insane delusions that he was personally molested by a man long dead and was pursued by evil spirits. In a famous judgment that still defines the legal test of testamentary capacity, the judge, Cockburn CJ, found that even though the testator had experienced these delusions, they had not interfered with his ability to make a valid will, a power that he described as follows:

‘It is essential to the exercise of such a power that the testator shall understand the nature of the act and its effects; shall understand the extent of the property of which he is disposing; shall be able to comprehend and appreciate the claims to which he ought to give effect; and, with a view to the latter object, that no disorder of the mind shall poison his affections, pervert his sense of right, or prevent the exercise of his natural faculties – that no insane delusion shall influence his will in disposing of his property and bring about a disposal of it which, if the mind had been sound would not have been made.’

Clinical negligence

Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee [1957] 1 WLR 582, [1957] 2 All ER 118

Mr Bolam required electroconvulsive therapy for depression, a treatment that carried a risk of bone fracture. At that time, some experts believed that it was better to give muscle relaxants to reduce the risk of fracture, some thought that it was better to restrain the patient using a sheet or similar device, and some felt that as little restraint as possible should be used. Mr Bolam was minimally restrained but sustained a fracture. He brought an action against the hospital for failing to restrain him and failing to warn him of the risk. McNair J held that the Court should ask whether the doctor was acting ‘in accordance with a practice accepted as proper by a responsible body of medical men skilled in that particular art’. In this case, the expert evidence showed that he was, so it did not matter that other doctors would have acted differently. The ‘Bolam test’ has been much criticised for setting such a low threshold for adequate medical practice that it is almost impossible to show that a doctor has fallen short of it.

Although later cases have slightly diluted the judgment (for example, in accepting that some expert opinion, although established practice, may yet be so unreasonable as to defy logical analysis), this test remains a key test in determining a doctor’s liability in negligence cases, as well as in many other areas of law, including non-medical ones. In terms of the information required to be given to patients, courts in the UK have avoided adopting the US test of what a prudent patient might expect to be told, in favour of asking what a competent doctor might consider that a patient should be told. In practice, professional codes of practice such as those from the General Medical Council and the British Medical Association are much more likely to inform medical practice in consent than standards enforced by the courts.

This case has two citations because it was published in two different series of law reports: Weekly Law Reports (WLR) and All England Law Reports (All ER).

Deprivation of liberty

The Bournewood case

This case started in the High Court (Queen’s Bench Division) as an action for habeas corpus and judicial review ( R v Bournewood Community and Mental Health NHS Trust Ex p L (1997) QB unreported), was then heard in the Court of Appeal ([1998] 2 WLR 764), then in the House of Lords ([1998] 3 All ER 289), and then went to the European Court ( HL v UK [2004] ECHR 45508/99).

HL was a man in his 40s with autism living with a foster family in the community. He was taken to a learning disability hospital after his behaviour became out of hand at a day centre. Even though he quickly calmed down, the hospital was so reluctant to allow him to return to his foster family that the family brought an action against the hospital for unlawful deprivation of liberty (an action of habeas corpus). The House of Lords found in favour of the hospital, saying that in English law HL had not been unlawfully deprived of his liberty, even though there was no formal legal process of detention (such as use of the Mental Health Act). However, the European Court of Human Rights found that his human rights had been breached and he had been unlawfully deprived of his liberty (Article 5 of the European Convention guarantees that ‘No one shall be deprived of his liberty save […] in accordance with a procedure prescribed by law’). Following this case, the law of England and Wales was declared to be incompatible with European law and was altered to provide a formal process for authorising and reviewing deprivation of liberty. This was why the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) procedures, which form Schedules A1 and 1A of the Mental Capacity Act 2005, were introduced.

Treatment under the Mental Health Act

B v Croydon Health Authority [1995] 1 All ER 683

For patients detained under the Mental Health Act, the question often arises as to what are the limits of treatments that can be given under the Act without the consent of the patient. The Act itself is very open-ended on this. Section 63 says:

‘The consent of a patient shall not be required for any medical treatment given to him for the mental disorder from which he is suffering […] if the treatment is given under the direction of the approved clinician in charge of the treatment.’

The leading case on this is B v Croydon Health Authority. Ms B had a borderline personality disorder coupled with post-traumatic stress disorder. While detained under section 3 of the Mental Health Act, she stopped eating and her weight became dangerously low. She sought an injunction to prevent the hospital from force-feeding her. The case was heard in the Court of Appeal, where Hoffmann LJ found that medical treatment as defined in section 145 must be considered as a whole, and ‘a range of acts ancillary to the core treatment fall within the definition […] Nursing and care concurrent with the core treatment or as a necessary prerequisite to such treatment or to prevent the patient from causing harm to himself or to alleviate the consequences of the disorder are, in my view, all capable of being ancillary’ [to the core treatment] and, therefore, permitted medical treatment. This case was applied in Tameside and Glossop Acute Services Trust v CH [1996] 1 FLR 762 to authorise a Caesarean section in a pregnant woman with schizophrenia who had the delusional belief that the doctors caring for her wanted to harm the baby.

Conclusions

This review has provided a brief overview of how the English legal system works in relation to mental health law, describing the structure of the courts and the role of law reports in understanding current law. It is not a summary of the present state of the law, but is intended to deepen psychiatrists’ understanding of how legal analysis can help to improve the quality of clinical decisions made in the often legally complex situations in which we work.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 The Supreme Court:

-

a is the highest court in England and Wales

-

b can overrule the European Court of Human Rights

-

c came into being in 1998

-

d contains the Court of Protection

-

e can accept some kinds of cases that have not first been heard at a lower court.

-

-

2 Law reports:

-

a cover all cases heard

-

b are governed by a unique citation standard, which was established in 1947

-

c can be found on the internet for new cases

-

d are indexed in PubMed

-

e report decisions that are always binding on all other courts.

-

-

3 Regarding consent:

-

a the rules are governed by the Consent Act 1984

-

b the requirement for patients to consent to a procedure helps to ensure that patients have autonomy over what happens to their own bodies

-

c medical treatment as defined by the Mental Health Act 1983 cannot extend to surgery

-

d if the patient is unable to consent for him/herself, consent must always be given by someone on behalf of the patient

-

e in the UK, patients have a legal right to be given as much information as a reasonably prudent person would want in order to make their decision.

-

-

4 When a bill is passing through Parliament:

-

a it is heard only once in each house

-

b it will be discussed in detail in committee

-

c it becomes enforceable as soon as Parliament has endorsed it

-

d it includes all of the detail needed to make it operational

-

e it is always introduced by the Government.

-

-

5 When citing cases:

-

a citations always start with the names of both parties

-

b citations give first and last pages

-

c it is not possible to tell in which court a case was heard from the citation

-

d any given case always has a unique citation

-

e new cases are cited in a standard way.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | a | 2 | c | 3 | b | 4 | b | 5 | e |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.