Introduction: The Idea of International Order

‘The league will have to occupy the great position which has been rendered vacant by the destruction of so many of the old European empires and the passing away of the old European order.’

‘It should be remembered that the members of the Secretariat are not representative of their countries. They are there solely as experts in law, economics, history and administrative problems. So they can and do approach problems with a scientific detachment which is novel in international affairs.’

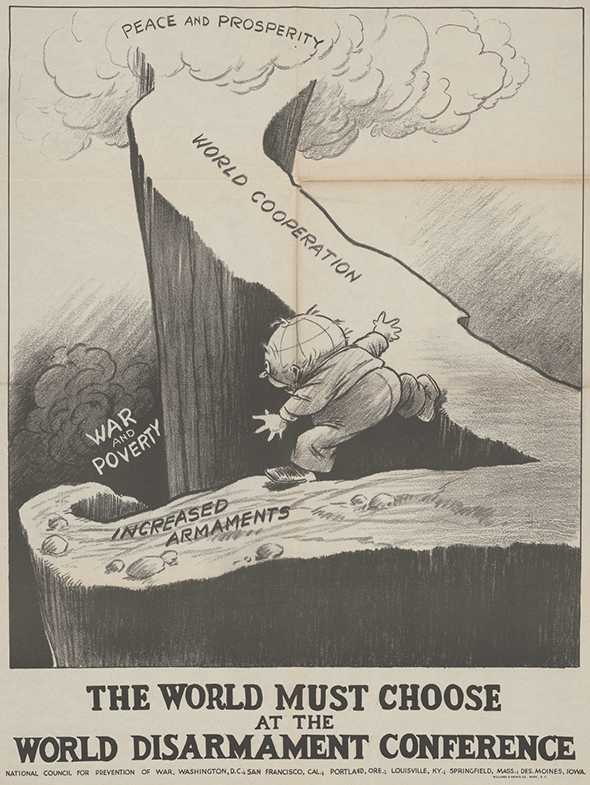

A first great experiment in international governance? A noble if abortive attempt to keep the peace in Europe? An unwitting but effective generator of new anticolonial pressures and decolonial sovereignties? Historians in recent years have placed the long-neglected League of Nations under a microscope, seeing in it the seeds of a postcolonial world order and a meaningful if flawed experiment in the mechanics of modern international political authority. The League now enjoys the reputation of a grand, but defeated, enterprise: one whose goals of maintaining the peace and preserving a new, semi-imperial economic and political stability ran up against unresolvable local, regional, and global contradictions, and eventually faltered altogether in the face of the simultaneous rise of Nazism and fascism. This League failed in its peace-making endeavours, but opened up new arenas of objection to empire, global economic cooperation, and international coordination of everything from currency stabilization to refugee aid. In this interpretation, the League – sometimes despite itself – acted as midwife in the birth of a modern era in which postcolonial sovereignties, human rights, and principles of international cooperation would enjoy a much-enhanced though never unchallenged status.

Such accounts have broadly failed to admit the League’s own overriding purpose. This was not to work towards international cooperation among equally sovereign states, or to promote economic stability in a shattered post-war Europe, or to ensure new forms of global security and prosperity. Rather, it was to claim control over the world’s resources, war-making potential, and populations for the League’s main showrunners – and not through the gentle arts of persuasion, collaboration, and negotiation but through the direct and indirect use of physical force and the monopolization of global military and economic power. The League’s advocates framed its structural and political innovations, from refugee aid to global labour regulation to disarmament, as manifestations of its evident commitment to an obvious universal good. But upon close examination all its practices pointed to the same goal: shoring up the dominance of the Western victors and preserving the structures of international power and the civilizational-racial hierarchies that had long sustained them, now in a form that could survive the fall of formal empire. In other words, the League of Nations was an experiment not in international governance but in the production, maintenance, and extension of imperially derived geopolitical hierarchies: organized around race, claiming near-total monopolies on wealth, and backed by overwhelming military supremacy and the perpetual threat (and not infrequently actual use) of physical violence.

This study seeks to outline the origins, philosophies, and practices of League from its inception to its dissolution, from two different perspectives: the bottom-up encounter with this forcible ordering of people and wealth experienced by colonial subjects and economically or politically subjugated regions of the post-war world on the one hand, and the top-down strategic view of ‘peace-making’ promulgated and institutionalized by its main (imperial) architects on the other. Its section order – People, Wealth, and War – reverses that of conventional treatments that view the League chiefly as an instrument for ending the First World War, and reflects a different understanding of the League as a colonial, imperial, and power-political enterprise. Taken together, these dual experiences of the League’s words and practice clearly indicated its primary reason for being: to order the world according to the (always contested and shifting) economic and political interests of its great-power sponsors and beneficiaries, including the United States.

Such a liberal imperial ordering of the world’s people and resources could – indeed, had to – be presented as a natural one, emerging uncontested out of the post-war era’s rule of experts and representing a neutral, scientific approach to the problems of global governance. Much of the League’s practice, then, was taken up with the active and conscious process of removing discussion from the realm of the public into the realm of incontestable forms of technical expertise – an approach that naturalized imperial hierarchy as scientific, and painted the myriad political objections to Allied agglomerations of power and resources, coming from all sorts of quarters, as mere ignorance or ineptitude. These rhetorical and procedural devices removed discussion of the League’s economic and political reordering of its realms from the dangers of public opinion; but, of course, they did not solve the problem of enforcement, which had to come from elsewhere – in the event, from the continued projection of ex-Allied military power into colonial and semi-colonial territories. The brutalities of the mandates system in the Middle East represented only one aspect of the violence and threat of violence that characterized the imposition of League-supported visions of order across the globe, from China to Africa to Latin America to Eastern Europe.

The League and Its Reception

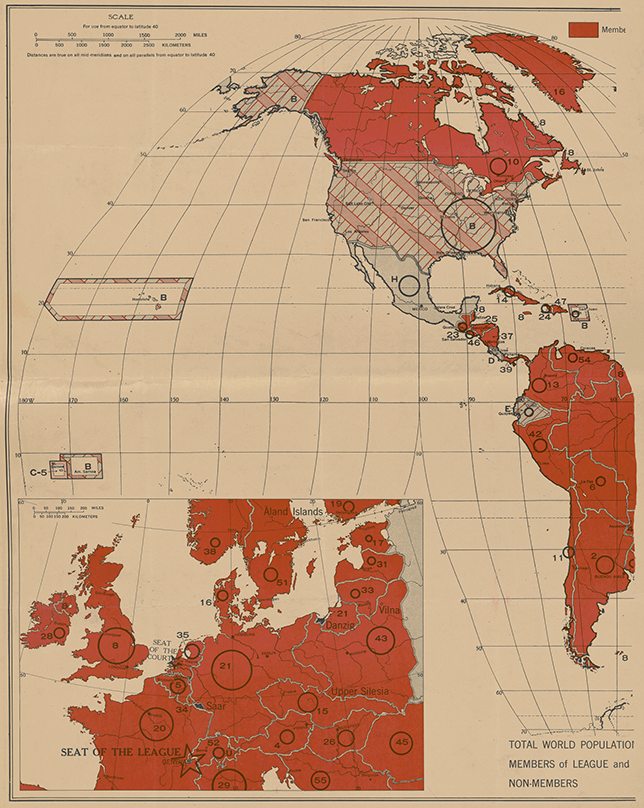

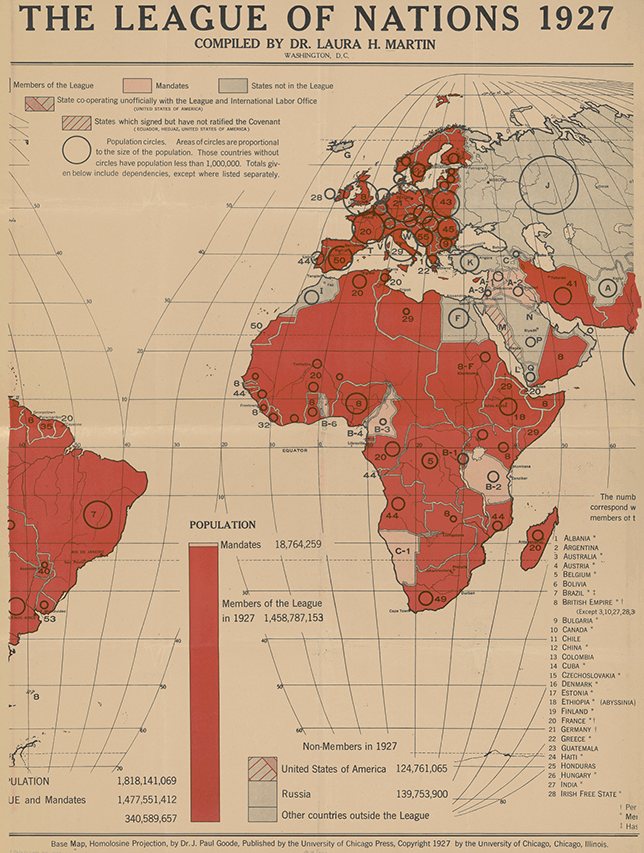

The League of Nations was the first global institution tasked with organizing international relations and shaping world order (see Figures 1a–c & 2). It was established at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, held its first meetings in Geneva in 1920, and was disbanded on 18 April 1946, when it turned its buildings, assets, and archives over to its successor, the United Nations.

Figure 1a Expansive vision of the global reach of the League of Nations, made by geographer Laura Martin (1884–1956), an expert on legal issues relating to sovereignty in Antarctica, in 1925/27.

Figure 2 League of Nations Building, New York World’s Fair, July 1939.

The League consisted of the Assembly, the Council, the Secretariat, and, from 1921, the Permanent Court of Justice (see Figure 3). The Assembly was a public forum for debate among the delegates of all member states, each of which had one vote on issues like the admission of new members and appointments to the Permanent Court of Justice. It also functioned as an advisory body on changes to international treaties, and oversaw the work of the Council and the League’s technical committees. The Council consisted of the most powerful members of the organization (initially Britain, France, Italy, and Japan) and a few additional non-permanent members. As the League’s top decision-making body, the Council deliberated on international disputes, acted on the recommendations of the Assembly, and nominated the secretary general. The Secretariat, as we shall see, was not simply a sprawling network of hundreds of administrators who ran the day-to-day affairs of the institution, but a diplomatic machine exerting influence across a broad range of political domains (colonial mandates, minorities, armaments, the world economy, cultural exchange, healthcare) through the dissemination of internationally legitimized knowledge and the application of technocratic expertise.Footnote 1 The same can be said of what was arguably the League’s most important additional agency, the International Labour Organisation (ILO), which drew on the expertise of the international socialist movement to promote social reforms through the promulgation of standards and regulations concerning such issues as working hours, child labour, and the employment of refugees.Footnote 2 Several other agencies claimed similar kinds of expert, scientific approaches: the Health Organisation, the International Commission on Intellectual Cooperation, the Permanent Central Opium Board, the High Commission for Refugees, and the Economic and Financial Organization.

Figure 3 Organizational structure of the League of Nations.

Legally, the League came into existence with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919 – underscoring the link between the outcomes of the First World War and the creation of a new institution intended to enshrine a post-war geopolitical status quo. Its Covenant consisted of twenty-six articles: seven establishing the rules and structure of the League, thirteen setting out its role in disarmament, collective security and international arbitration, and six recognizing the Monroe Doctrine (US dominance in the western hemisphere) and proposing principles of governance for colonial ‘mandates’, national minorities, and cooperation with the International Red Cross. Membership in the League was voluntary, though Germany was excluded until 1926. Over the lifetime of the League, sixty-two recognized sovereign states became members at one time or another; in 1937–38 it still had fifty-three active members.

Over the course of the past century, interpretations of the League have gone, very broadly speaking, from boosterism to condemnation to a kind of attenuated enthusiasm. In the hopeful but psychologically difficult terrain of the early 1920s, Western descriptions of the League featured buoyant narratives about its pacific possibilities and its utopian visions. (Soviet sources, equally reflective of their own political context, viewed it mainly as an extension of nineteenth-century British and French imperial expansion.) During periods of time when the outlook for what liberal observers thought of as cooperative internationalism seemed bleak – in the run-up to the Second World War and then again through the Cold War years – the League was broadly condemned as a failure. In the post–Cold War era of unipolarity and a sense of the permanent triumph of liberal capitalism – Francis Fukuyama’s ‘end of history’ – it once again transformed into an inventive, promising, and at least semi-successful gambit. More recently, following the myriad failures and humiliations of liberalism from the ‘war on terror’ forward, specialized works from various quarters have begun to reconsider this position, seeing in the League something distinctly more menacing. It is time, perhaps, to collate some of this contemporary work into a broader reconsideration of the intent, meaning, and consequences of this first experiment in global governance – with an awareness of the ways in which both scholarly and popular interpretations of the League’s role, actions, and legacies have tended to serve not just as evaluations of the past but also as assessments of the present.

The earliest accounts of the League, coming particularly from legal scholars interested in emerging concepts of internationalism (and including not a few who had themselves participated in the League’s construction or early operations), tended to emphasize its stated ideological commitment to global peace and stability and its initial successes in ‘technical’ realms like refugee resettlement, currency stabilization, and the distribution of raw materials. But following the League’s dissolution in the late 1930s and the advent of an even more catastrophic global war, scholarly enthusiasm for the League died down. The few works produced on the League in the aftermath of the Second World War tended, as one historian has put it, to represent ‘“decline and fall” narratives or analytical postmortems’ – painting a picture of its tragic descent, in just a few decades, from high hopes and higher ideals to disillusionment and collapse.Footnote 3 In the aftermath of the Soviet Union’s disintegration and the end of the Cold War, though, a new and explicitly revisionist narrative began to dispute this apparently long-settled story about the ‘failures’ of the League of Nations. Now, international historians searching for histories of (and, perhaps, models for) global institution-building in this brave new unipolar world of hyper-globalization and liberalization began to see the League in a new light: not as a failure but as a useful, interesting, and innovative experiment, one whose successes were as real as its disappointments and whose enduring influence had long been underrated or misunderstood. As historian Susan Pedersen put it in an influential 2007 essay,

if these League systems could not coerce states or override sovereignty, they did contribute powerfully to the articulation and diffusion of international norms, some of which proved lasting … The League was the training ground for these men and women – the place where they learned skills, built alliances, and began to craft that fragile network of norms and agreement by which our world is regulated, if not quite governed.Footnote 4

Pedersen was one of several prominent scholars who, if they retained some of the critiques of the previous generation, nevertheless saw much to like in the League. Akira Iriye’s 2002 book Global Community understood post-1919 internationalism as an essentially cooperative endeavour, interrupted rather than prompted by the war and bringing an ideology of global cooperation to an otherwise brutal interstate system during the interwar period. ‘International institutions, both governmental and nongovernmental,’ he wrote, ‘represented the conscience of the world when individual states were destroying the peace … Global consciousness was kept alive by the heroic efforts of nonstate actors that preserved the vision of one world.’Footnote 5 While not quite so unreservedly complimentary, Patricia Clavin’s 2013 book Securing the World Economy, on the League’s Economic and Financial Organization, likewise understood League-led internationalism to have made notable strides towards an integrated world. ‘The multiplicity of activities and perspectives frequently rendered the whole League ineffective in an international crisis,’ she wrote,

yet it simultaneously meant that, out of the diversity of its responses, information was exchanged, and national positions clarified in a process that, over time, opened up the possibility for different outcomes in the future. It also allowed for fruitful connections to be made across spheres, such as economics and health, or finance and security, which may have been impeded by the creation of discrete institutions.Footnote 6

Both these authors noted especially the League’s commitment to and successes in arenas of ‘technical’ knowledge and information-sharing across borders: reconstruction, food provision and distribution, labour controls, health initiatives, to name a few. In such readings, if the League had failed to bring ‘security’, it had nevertheless promoted international cooperation in ways that presaged positive aspects of the internationalisms of our own era. As Glenda Sluga, Peter Jackson, and William Mulligan put it in perhaps the most recent restatement of these arguments, ‘The UN, European integration, decolonization, greater popular participation in international politics, the codification of international law and the restraints on power politics had their roots in the possibilities of peacemaking after the First World War.’Footnote 7

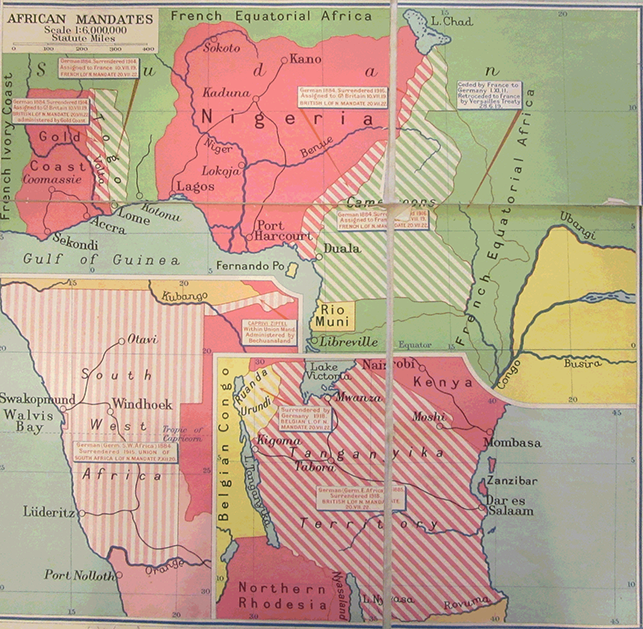

In her book-length exploration, Pedersen even managed to bring such arguments to one of the most-reviled aspects of the League: the mandates system. The Guardians: The League of Nations and the Crisis of Empire represented the first history of the Permanent Mandates Commission (PMC), the League’s governing body for its colonies-lite system under which certain of the Allied powers were issued responsibility for the administration of ex-Ottoman and ex-German colonial territories ‘inhabited by peoples not yet able to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world’, as the infamous Article 22 of the League Covenant put it. While acknowledging the colonial nature of the mandatory system and its promotion of racial hierarchies of civilization and sovereignty, Pedersen nevertheless viewed the PMC as a site of productive internationalist discourse that wrought more than it intended. ‘The mandate system,’ she wrote, ‘opened up imperial rule to an uncontainable wave of scrutiny and “talk” … the League, against its own desires and intentions, helped to bring the European empires down.’Footnote 8 In this reading, the League’s pledges to ensure public review and discussion of its actions collided with its basic commitment to empire, opening up the mandates to global critique of a sort that eventually managed to bring the whole system into question and created a new international landscape inclusive of newly decolonial sovereign states.

Such revisionist arguments did not go unchallenged for long. One critic, the influential historian of Europe and the Balkans Mark Mazower, staked out an at least half-sceptical position in his 2012 book Governing the World: a work that repeated shibboleths about the success of the League’s ‘technical’ work, but also offered a sharp critique of the idea that the organization somehow inadvertently opened the doors to imperial dissolution. ‘In a small way, perhaps, by establishing the principle of international oversight and making it respectable,’ he noted, ‘the commission paved the way for post-war decolonization. But it is worth asking how long the colonies might have remained under imperial or mandatory rule had the Second World War not intervened and American anticolonialism (and America’s fear of Bolshevism) not been added to the mix.’Footnote 9 The idea that the League could, even unwittingly, be an agent of any kind of liberation was met with even greater scepticism among scholars whose work was based in the regions that had found themselves under mandatory rule, most notably the Middle East and Africa. The 2015 Routledge Handbook of the Middle Eastern Mandates, co-edited by historians Andrew Arsan and Cyrus Schayegh and conceived as an update to a similar 2004 collection by Peter Sluglett and Nadine Méouchy, depicted the mandates not just as a continuation but an extension, both geographical and territorial, of old and brutal forms of racial empire.Footnote 10 Similarly, recent scholarship on Africa has not, by and large, been willing to accept the rosier conclusions of Europeanists like Pedersen vis-à-vis the liberationist possibilities of the mandate system or (by extension) the League. As Molly McCullers has recently put it with reference to mandatory Namibia, histories from the perspective of the colonized put paid to the idea that the mandate system opened a path to decolonization despite itself, instead illustrating mainly ‘how the mandates’ purposeful indeterminacy could delay a territory’s rite of passage from colony to nation-state and indefinitely extend its liminality’.Footnote 11

The most recent assessments of interwar internationalism, perhaps reflecting a greater distance from the triumphalism of the post–Cold War years and a rather more pessimistic view of the longer-term ramifications of an untrammelled global neoliberalism, have begun to suggest that the League – and in particular its economic policies – was mainly concerned with protecting the principle of private property and controlling the international distribution of labour rather than the promotion of world peace and international security.Footnote 12 This is especially true of economic historians who have cast a critical eye on the machinations of twentieth-century global capitalism, and of more semiotic approaches that understand the League as (in Carolyn Biltoft’s words) ‘a truth and symbolic capital production system’.Footnote 13 Still, even this recent literature has often retained the old commitment to the idea of international order as a self-evident good, and continues to single out the League’s ‘technical’ bodies for approbation even while acknowledging the long-term consequences of the League’s neo-imperial practices. Historian Sandrine Kott’s notes on the ILO represent a good example: while she acknowledges ‘a fundamental tension … between the promise of social justice and the decommodification of labour that this promise embodies and its role as a social agent of economic globalisation’, she also takes note of its ‘normative work, based on a skilful exchange of ideas between ILO officials and those of national administrations, [that] enabled the establishment of a recognised social expertise and know-how’ – norms that remain ‘important reference points even when they are not ratified’.Footnote 14

One of the questions that a history of the League brings up, then, is: Should we understand the effort to build a liberal internationalism, in itself, as a worthy goal aimed at the creation of a more secure and just world? Historians have tended to think the answer is yes; as Mark Mazower has put it, ‘their guiding assumption seems to be that the emergence of some kind of global community is not only desirable but inevitable’.Footnote 15 While often decrying the severely punitive elements designed to hold Germany and its allies accountable, historians’ assessments routinely balance this punitive impulse with what they see as a positive attempt to transcend the war-prone anarchy of pre-1914 imperialism by organizing peace and ‘security’ in the form of the League. Within the universe of historians, Waqaf Zaidi’s assertion that such ‘security’ was built mainly to guarantee ‘the ongoing subjugation of [the Allies’] enemies’ represents an outlier positionFootnote 16 – one more in line with political scientists, who have often answered this question rather differently. From this disciplinary perspective, it is more common to consider international order building to be at best normatively neutral and in any case profoundly implicated in the maintenance of imperially derived geopolitical hierarchies. The work of scholars like Lora Anne Viola and Kyle Lascurettes suggests that after great wars emerging hegemons do not generally seek to make their rule acceptable to other states by constructing inclusive world orders; instead, they establish ‘exclusive orders’ to inhibit the emergence of future great power threats.Footnote 17 The overriding logic of ordering is thus competition, exclusion, and stratification – precisely what we can see emerging from the post-war negotiations from 1919 and in the construction of the League itself.

If, then, the current literature features a still-dominant view that the League represented a sphere for ‘progress’ – albeit an incomplete and politically compromised version – it also includes a number of more critical (and, often, more locally specific) takes on the League as a complicated and temporary but nevertheless insidious, effective, and influential agent of empire and its attendant radical inequalities. It is with this historiographical tension in mind that we will begin our own explorations.

Long-Term Origins

The League of Nations had two major points of origin, both centred on ‘great power’ interests: nineteenth-century British and French imperial practice, translated for a new global audience and adjusted to accommodate shifting discursive norms, and a more immediate set of wartime imperatives for the preservation of the liberal empires in a moment of global conflagration.

Internationalism as both idea and practice had deep roots in the nineteenth century: not only in the imperial agreements and carve-ups emerging from the Congress of Vienna and its many later iterations, but also in the emergence of non-governmental institutions that appeared humanitarian or pacifist but in fact were designed to support ever more expansive applications of imperial rule. ‘International’ cooperation in the form of distribution of territory among empires found its most explicit moment in the Berlin Congress of 1884, which in its unabashed handing-out of African land to the European empires arguably prefigured the League’s parcelling out of former Ottoman and German territories to the Allied powers; certainly, the concept of a European concert underpinned the idea of the League. But there were other, less overtly political actors involved as well, who were collectively transforming the exercise of nineteenth-century empire into an all-inclusive internationalist practice. Some had to do with negotiations over cross-border communications, like the International Telegraphic Union (established in 1865) and the Universal Postal Union (1874). Others had more explicitly to do with the nature and conduct of war: most notably perhaps the International Committee of Red Cross, established in 1863 by international treaty and embedded at the national level in military and especially army practice. Health, too, became a venue for international cooperation through such new organizations as the International Central Bureau for the Campaign against Tuberculosis.Footnote 18 All these theoretically non-political enterprises were deeply engaged with national governments, and they all provided imperial venues for the active and ongoing negotiation of local and regional conditions in the run-up to the First World War, as the window for claiming new territory appeared to be closing. Such organizations assumed the possibility of regulating conditions of conflict from a supranational stance, approved and moderated by states themselves. In other words, these collaborations in the realms of communications, cultural exchange, health, and the rules of war all sought to stabilize the imperial system by producing limited but meaningful venues for the negotiation and pre-emption of potentially clashing imperial claims through external controls on local conditions.

In addition, the late nineteenth century saw the major European empires increasingly encouraging, and sometimes actively constructing, communalism and nationalism as spheres for various forms of ‘internationalist’ intervention. Philo-Hellenic associations supporting Greek resistance to the Ottomans and the construction of a territorially ambitious Greek state, for instance, positioned Western European Christian support for Greek separatism as a kind of internationalist cause tied to liberal political commitments. Many observers on the ground noted that such interventions, tagged as liberationist and internationalist, in fact often served to stoke the kind of local, intercommunal violence that would eventually produce highly exclusionary forms of nationalism and render multinational communities untenable; but they served the cause of empire in their production of ragged, weak separatist states that needed Western European imperial backing to survive.Footnote 19 Similarly, the Berlin Conference’s positioning of the Ottoman treatment of its Armenian communities as a site for international monitoring and if necessary intervention served primarily not to benefit Armenian communities themselves (whose position in the empire was in fact substantially damaged by this imperial association) but to provide Britain and France with a legitimization of political, military, and commercial intervention in the Ottoman sphere, particularly against Russian interests.Footnote 20 Even the Red Cross, so apparently humanitarian in its purpose and operations, arguably smoothed the path for imperial violence – perhaps particularly in the Balkans – by assuming the basic legitimacy of contemporary forms of bloodshed, and assuring an anxious metropolitan public of the active mitigation of their most brutal aspects.Footnote 21 (On this point, it is perhaps worth noting the concentration of such relief schemes in areas of conflict where the concept of ‘rules of war’ were broadly agreed not to apply.Footnote 22)

The League would also draw heavily on one of the crucial concepts of nineteenth-century empire: extraterritoriality. Developed with special reference to spaces of informal imperial influence, notably China and the Ottoman Empire, ideas about the creation and enforcement of special spheres of economic, political, and military operation would become central to the League’s conception of its own role and the exemptions it was providing to its primary showrunners. In the Ottoman sphere, the role of the so-called capitulations treaties – agreements exempting foreigners from adherence to Ottoman law and taxation, dating from the seventeenth century and by 1914 one of the most reviled aspects of the Ottoman–European relationship – was recast by Britain, France, and the League in the mandate texts to ensure the continuation of the previous era’s commercial privileges for European firms operating in the Levant. Nineteenth-century practices around the capitulations also provided a model for how to cast ‘minority rights’ as a legitimate internationalist site of concern and action in semi-colonial areas of the world.Footnote 23 Debt, too, persisted as a venue for intervention; the League’s enforcement of repayment terms for imperial debts offered a liberal rationale for a continued imperial presence across the Middle East and Asia that clearly recalled nineteenth-century British and French practice in places like Egypt.Footnote 24

Short-Term Origins

All these precedents enjoyed a renewed relevance with the rise of new forms of Allied cooperation, particularly with respect to money and raw materials, during the First World War. As early as 1915, the Allied representatives were discussing economic cooperation as a basis of their collective military effort – as Lloyd George put it, constructing ‘not only an alliance of military forces, but an alliance of financial forces’.Footnote 25 Historian Jamie Martin has traced the development of large-scale forms of wartime cooperation around the acquisition of raw materials, from the early establishment of the Commission Internationale de Ravitaillement (International Resupplying Commission) in 1914 through a series of agreements on wheat prices in the middle part of the war to the eventual emergence of the Allied Maritime Transport Council, which included the United States in its organization of imports and pricing vis-à-vis the Allied powers.Footnote 26 This sort of inter-imperial cooperation, eventually encompassing the United States as well as the Entente, was from its inception viewed as a potential model for post-war cooperation with an eye to permanent Allied hegemony.

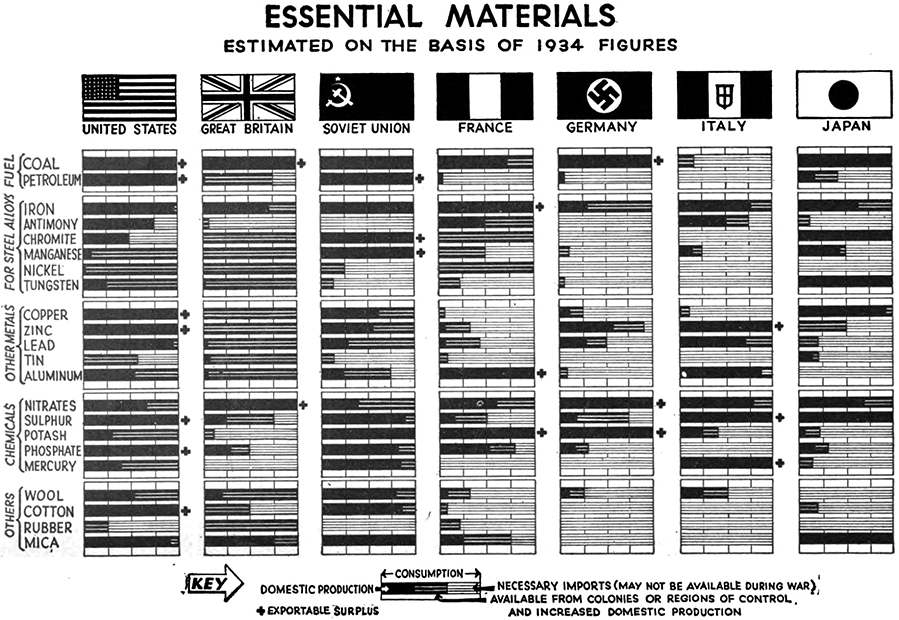

In all these cases, concerns about scarcity mobilized Allied officials to look for collective and collaborative ways to guarantee access, at the lowest possible cost, to all the raw materials necessary for the continuation of the war, from minerals to foodstuffs to fuel. Indeed, it was worries about shortages that led to early proposals that the League should have the power to engage in economic sanctioning to protect access to raw materials and thereby ensure the full employment necessary for post-war stability.Footnote 27 But as the war drew to a close, it gradually became clear that the real issue for the surviving empires (including the United States) was not scarcity but the spectre of overproduction and price collapse. Over the coming years, then, the League would re-commit to the concept of free trade zones (physically enforced by some of the bloodier aspects of the League, particularly its mandate system), combined with limits on production across imperial spheres. This internationalist version of earlier imperial cartels drew simultaneously on wartime cooperation and nineteenth-century imperial practice, now in the name of global collaboration.Footnote 28

Further, the imperial internationalism codified in the peace treaties and in the League’s founding documents was based in an already-extant economic and political order produced by Allied military efforts, particularly though not exclusively in the Ottoman sphere. Historians’ fixation on the thinking of US president Woodrow Wilson, and his disputes with his British and French counterparts, has tended towards allowing the rhetoric of liberal peace-making to obscure this competitive reality of geopolitical outcomes and the basic violence on which the League’s global order was based.Footnote 29 Even more fundamentally, it also confuses the order of events: for the military, political, and economic basis for League governance rested above all on wartime practices of occupation, resource allocation, and control of populations, all established some time before Wilson declared in Paris that the conference would replace the balance of power with ‘a fair and just and honest peace … in a which the strong and the weak shall fare alike’.Footnote 30 By the time an internationalist case was being made for the League’s oversight of the Central Powers’ former colonies via the new ‘mandate’ system, the occupations that such words were designed to describe were already fully operational and clearly looking towards the long term. Regimes surrounding refugee encampment, removal, and repatriation, from Eastern Europe to Iraq, were likewise already fleshed-out realities on the ground when they received their rhetorical legitimization via the new League offices. The Allies had also hammered out many of the agreements surrounding the imperial division of crucial resources and raw materials – oil not least among them – during the war itself. In other words, the kind of internationalism that the League promoted was first practically and logistically established in the context of wartime military encounter and then described and legitimized as a novel form of promoting international peace, order, and security.

To recap, then, our contention here is this: Making use of nineteenth and early twentieth-century models of imperial accommodation, now joined with practices of inter-Allied wartime cooperation vis-à-vis materials and money, the League of Nations established what international relations scholars might call a global ‘order of exclusion’: one that would permanently prevent defeated foes (not to mention the Soviet Union) and subaltern League-adhering empires like Italy and Japan from mounting successful challenges to the order dominated by the United States, Britain, and France. Its particular form of ordering had nothing to do with global security for the vast majority of the world’s population; it was designed to uphold a long-standing political hierarchy privileging the interests of the British and French, and now the American, empires above the rest of Europe and permanently sealing colonial territories into a subservient position of resource and labour provisioning – with or without some theoretical form of ‘self-determination’.Footnote 31

The United States and the Soviet Union

In this reading, the League was very far from a failure: in fact, as the actual aftermath of the war demonstrated, the League’s efforts to build a world order of more or less permanent inequality succeeded brilliantly. Combining the language of liberalism with a commitment to technocracy and ‘expertise’, the League’s practices removed basic questions of resources, labour, migration, and finance from the realm of the political, thereby seeking to protect the imperial powers from the likely objections of a vast majority of the world’s population and more broadly to delegitimize popular protest. Further, it built on its members’ wartime practice by formally endowing the former Allies with the right to use physical force in ‘internationally’ governed spaces, strictly regulate global labour and migration, and maintain free trade zones in ways that could ideally be maintained even in the case of some eventual form of independence. (In the event, we might note, these largely did hold – long outlasting the League itself, and surviving any number of forms of sovereignty and independence eventually achieved by the ex-colonial and ex-mandatory territories.)

One of the most important, and most overlooked, aspect of this strategy was its strategic inclusion of the American empire without that nation’s formal membership. This new world order depended quite heavily on American participation, not least because of its crucial status as Europe’s creditor in the post-war rebuilding efforts. And the same was true in reverse: despite the League’s posthumous reputation as an organization of no great power, the United States found its existence and influence to be invaluable as new visions for a specifically American form of economic empire incorporated any number of League practices vis-à-vis labour migration, forcible deportation, and external forms of political/military control in its relations with Mexico and Latin America.Footnote 32 Apart from this sharing of influences, the League’s ‘technical’ bodies were the main site for active American participation, particularly the private variety. American private though state-linked organizations (most notably the Rockefeller Foundation and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace) donated somewhere between $5.5 and $6.5 million to League organizations, with another $10 million coming in to its educational and research initiatives. This set-up guaranteed American influence in interwar internationalism, while shielding the government from the domestic repercussions of official participation.Footnote 33 Eventually, this involvement became more formalized. In 1934, the United States formally joined the ILO; in 1940, as the League was threatened by the German triumph, its Economic, Financial, and Trade Department was transferred to Princeton.Footnote 34 The US participation in all these bodies served to integrate the scope of American imperial activity into the League’s vision for protected zones of economic activity, great power control over raw materials, and limits on migration across the globe.

This truth – and, in fact, the more general realities behind all the League’s practices – remained opaque to many liberal observers within the Allied metropoles who were willing to accept many if not all of its claims about commitments to peace, security, and justice and who continued to see the US formal refusal to join as a death blow to internationalist cooperation.Footnote 35 It remained opaque even to some degree in the colonies, where hopeful nationalists sometimes saw in the League’s messaging (if not in its actual operations) an openness to the possibilities of independence and a more equitable international system. But there was at least one actor on the global stage who understood both the purpose of the League and the American role in it: the emerging Soviet Union. ‘That contemptible agency of imperialism,’ declared Lenin about the League. ‘It has become one of England’s diplomatic offices.’Footnote 36 Getting to the heart of the League’s commitment to the privileges of empire, Lenin also told the British public in 1922 that the League’s approach was ‘marked by the absence of anything resembling the establishment of the real equality of rights between nations’Footnote 37 – a charge clearly demonstrated to be true as the details of the mandate system, among other things, were gradually rolled out. The League’s profound hypocrisy on the question of disarmament was likewise highlighted by its rejection of (no less hypocritical) calls by the Soviet Union for total disarmament in the 1920s. Even after the eventual Soviet admission to the League, in 1934, the USSR continued to act as a kind of gadfly pointing out the organization’s failures and insincerities. One early historian of the League, speaking of Maxim Litvinov’s commentaries in his role as People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs, understood Soviet critiques as among the sharpest observations of the moment: ‘Nothing in the annals of the League can compare with them in frankness, in debating power, in the acute analysis of each situation.’Footnote 38

At the same time, the construction of the Soviet state also at times reflected the goals and priorities of the League of which its representatives were officially so critical. Lenin and then Stalin, too, were interested in the creation of novel imperial spaces; in the protection of markets; in state and superstate control over migration and labour; in finding ways to guarantee supplies of raw materials and stabilizing credit; and in configuring the rules of warfare and arms control to favour the spread of revolution and to outlaw an invasion of the Soviet Union. If American forms of influence in Latin America at times resembled mandatory authority, so too did Soviet policy vis-à-vis its own varied subject peoples. Further, the Soviets sometimes sought to create their own forms of internationalism that reflected imperial hierarchies much as the League’s did; if the United States understood internationalism as a potentially valuable ally in its construction of a new kind of post-war economic empire, so too did the Soviet Union.Footnote 39 The eventual construction of a United Nations with the imprimatur of both the United States and the USSR reflected, perhaps, a clarified understanding on the part of all of the Allies about what this new version of the League was actually intended to do. As Stalin would put it in 1944, what mattered was ‘not that there are differences, but that these differences do not transgress the bounds of what the interests of the unity of the three Great Powers allow’.Footnote 40 In its revised iteration, there would be no question about whose interests this form of internationalism was built to serve.

The argument that liberal internationalism, in the shape of an admittedly deeply flawed but at least sometimes well-intentioned, League, unwittingly sowed the seeds of its imperial architects’ own destruction allows liberal internationalists to claim a double virtue: good intentions vis-à-vis peace, security, and cooperation in the first instance, and an unintended but ultimately productive move towards decolonization in the second. Neither of these claims holds up under close examination.

First of all, the League’s founding had next to nothing to do with pacifist aims or new visions of a genuinely internationalist society. Rather, it drew on a variegated combination of nineteenth-century European forms of collaborative, negotiated imperial domination and the immediate wartime collaborations designed to ensure the conditions necessary for an Allied victory (and manifest in the evidently long-term military occupations of the war’s later stages). Both of these precursors assumed the virtue in maintaining the world for empire and ensuring conditions of cooperation vis-à-vis threats of imperial dissolution. In this respect, we might well suggest that the League’s primary novelty lay not in some new internationalist imaginary but in its active inclusion of American private capital in its program for global imperial rule – and, perhaps, in its active and explicit centring of economic (rather than military or political) foundations of long-term imperial domination.

The argument that the League accidentally opened the door for decolonization by making public its discussions and creating a new sphere for ‘talk’ is equally mistaken. In fact, the League sought to delegitimize and disempower its anticolonial opponents by ensuring the ultimate meaninglessness of all forms of discursive protest embedded in its operations, from its practice of conveniently vanishing petitions of protest to its mandatory representatives’ punitive use of censorship to its near-total sublimation of local representation in the mandate territories. The League’s active disappearance of any kind of verbal protest had the effect of forcing local turns to violence – which, of course, could then be interpreted and presented as precisely the kind of ‘disorder’ the organization’s long-term presence was intended to pre-empt. In other words, the League’s active production of discursive venues for public objection that would have no meaningful outcome did two things, both more or less deliberate: it denuded peaceful protest of any political power, and it encouraged the emergence of non-peaceful forms of protest whose evident threat could further and extend League influence in the colonial world, perhaps forever.Footnote 41

Of course, this project of order and domination was always a work in progress facing both internal dissent and external pressures; and the League’s eventual collapse under multipronged attacks on the post-1918 status quo spoke, above all, to the ways in which it was intended to defend a very specific – and, as it turned out, fundamentally unstable – vision for a permanent international, geopolitical, and imperial hierarchy. Nevertheless, its survival through the two decades of the interwar period with many of its basic structures intact served as testament to its longevity and (despite roadblocks) its consistency. Whatever the impressions of a disappointed European public, from the perspective of its more directly governed populations – global labourers working under its regulations, migrants seeking its imprimatur for border entry, and corporations looking to its loans and financial guarantees – the League looked much the same before and after the financial crash of 1929, the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, and even the German occupation of the demilitarized Rhineland in 1936, all later viewed as markers in the collapse of the internationalist project. Its story did not end even with the war: many of the League’s fundamental precepts survived in wholly recognizable form in its next incarnation after 1945, and continue to inform and structure the geopolitical hierarchies of the contemporary era. Indeed, the architects of the League might find the modern world, with its hierarchy of nations all too often understood as a kind of natural and even inevitable geopolitical phenomenon, to serve as a reassuring monument to their continued relevance in a supposedly postcolonial world.

1 Ordering People

Control over territory, resources, and wealth – to be reserved for the use and the benefit of the imperial powers, including the United States – could not be accomplished without first establishing control over populations. In the upheavals following the armistice, the chaotic remaking of population politics via forcible and coerced migrations, border changes, nationalizations and denationalizations, the installation of global labour controls, and the creation of new categories of refugeehood and statelessness all appeared to the League’s leadership as both hazard and opportunity as they began to set the stage for a new global order. Though these missions have often been regarded as secondary to the League’s security and economic concerns, or set aside as ‘technical’ operations that could be assessed separately from its more central operations, we begin here for good reason: because this ostensibly scientific, humanitarian, and bureaucratic work actually constituted the bedrock on which the League’s political and economic controls would be built.

First among the League’s post-war missions was the determination and enforcement of new borders in Central and Eastern Europe and across the old Ottoman territories of what was now being called the Middle East. For all the talk about ‘self-determination’ and the rights of small nations, the new borders in Eastern Europe, the Balkans, and the Middle East were drawn up mainly with reference to economic and strategic interests of the major powers; the negotiations over them featured a near-total disregard of the interests or preferences of populations on the ground, despite considerable efforts by local actors vis-à-vis questions like Czechoslovakia or an expanded vision of Greece. The settlements sought, in broad strokes, to settle inter-imperial disputes over the boundaries between British and French power and to establish the League as the final arbiter of any post-war map. To this end, it proved convenient that so many of the new state borders produced newly nationalized majorities but also newly emergent ‘minorities’, long-standing and well-established but now suddenly politically vulnerable communities. Their existence had the undoubted capacity to undermine any number of post-war national projects and threaten the continent’s stability; but their evident fragility and their need for some kind of external guarantee of security could also give the League an indisputable raison d’être and serve as a venue for post-war Allied intervention in the affairs of theoretically sovereign states. Such ostensibly bureaucratic mechanisms of ‘protection’, then, were not mere window dressing; they actively and deliberately formulated the conditions for the Allies to pursue a top-down material and geographical ordering of some of the messiest territorial dispositions of the post-war era.

The physical dislocation of populations likewise represented both problem and solution for the Allies and their League. Wartime and post-war expulsions, particularly the mass flight of Anatolian Christians into Greece as Mustafa Kemal’s nationalist armies advanced on Smyrna, suggested to the League the possibility of serving as an institutionalized arbiter of a general ‘unmixing of populations’, as the British diplomat Lord Curzon had so memorably put it.Footnote 42 The League’s role in the brutal compulsory population exchange between Greece and Turkey, formalized in the war’s final treaty in 1923, made it into a new kind of entity: one that could make or break new states, and that had the power to set the bar of entrance for nationality and citizenship. Here, again, these supposedly benevolent interventions made possible the creation of Allied-ordered states and citizen bodies – not to mention channels of money, investment, and development – that belied the League’s presentation of its actions as humanitarian and ‘technical’ rather than political, economic, or military.

Mass dislocation offered other kinds of opportunities as well. For those not to be renationalized by forcible transfer, the League created novel documentary categories controlled by its member states: most notably the so-called Nansen Passport, an early experiment in remaking refugees into guest workers whose labour could serve as an asset to willing host countries. For the next decade, the League sought to place refugees in low-wage employment outside Europe – particularly in Latin America, where such provision of workers could tie together the interests of the European empires and a United States increasingly invested, both economically and politically, in its southern neighbours. This kind of labour migration could also help support an order to which the League was very deeply committed indeed: a global hierarchy of wages and working conditions. The League repeatedly and publicly declared its dedication to the protection of workers in the metropoles while ensuring the legalized continuation of sub-par conditions and remuneration, including internationally authorized forced labour, in the colonies. In its external setting of the conditions for highly inequitable forms of international labour distribution and remuneration, the League was establishing a crucial mode of global economic control that might be able to survive any number of shifts in the political winds.

And finally, the League found still another way of controlling populations: through direct rule. Its ‘international administration’ of the Free City of Danzig and the mandatory territory of the Saar gave the League a new avenue for its pursuit of political power. This direct assertion of political power over some of Europe’s most contested land, over the protests of their populations, provided venues for thinking through the practicalities of a technocratic internationalist rule: one that would claim a progressive modern politics while actively suppressing claims to democratic representation in the actual territories it controlled. Technical capacity, developmentalist expertise, and humanitarian intervention did not constitute some secondary level of League practice to be judged in isolation. To the contrary, these were the basic tools that laid the groundwork for the League’s political and economic ordering of the globe to benefit its primary members.

The Making of Borders

Quite early on in its tenure, the League’s Allied constituencies coalesced around two apparently irreconcilable ideas about borders. On the one hand, they hoped for the eventual re-emergence of a global system of open trade and passport-free travel, a return to the economic conditions of nineteenth-century imperial liberalism. On the other, they were also increasingly committed to the idea that visible and enforceable borders were a crucial element of the geopolitical order their League was building – an idea that came out of an already-extant hope in imperial circles, especially the British variety, that rising nationalisms across the empire and the globe could be turned to imperial advantage.

The rising fortunes of racialist thought gave a decisive boost to the second impulse. The early 1920s saw the former Allied powers, for the first time in their histories, doubling down on broad and punitive immigration restrictions as a protective measure, understood in both ethnic and economic terms. ‘It is preached that the highest human type is the Nordic type, the fair-haired and blue-eyed people of North Europe,’ one newspaper in Jamaica reported on this new development, ‘and the aim of those in America who have been captivated by this doctrine is to keep America for the Nordic type.’Footnote 43 Such racial interpretations of these new policies were not mistaken. One of the League’s main architects, the South African politician and writer Jan Smuts, rooted his original vision in the concept of white supremacy and segregation – a vision shared across the Allied political landscape and inclusive of American thinkers like Woodrow Wilson. As Smuts put it in 1930, ‘The mixing up of two such alien elements as white and black leads to unhappy social results – racial miscegenation, moral deterioration of both, racial antipathy and clashes, and to many other forms of social evil’Footnote 44 – an assessment that tracked closely with Wilson’s own positions vis-à-vis race and segregation, not to mention long-standing racial assumptions of British and French imperial thought.Footnote 45

Further bolstering the idea of defined, defensible borders were old lines of thought about how nationhood and nationalism could represent valuable new venues for imperial clientelism. From the nineteenth century forward, for instance, the emergence of Greek national claims against the Ottoman Empire came to be seen as a path to British influence over a weak and peripheral state. The ‘protection’ of Maronite Christians in Mount Lebanon similarly appeared to open up new possibilities for French commercial, military, and political presence in greater Syria. Sometimes, active engagement with nationalisms became an explicit strategy for turning forms of anti-colonial protest into submerged aspects of imperial rule. The admission of the possibility of Home Rule for Ireland, for instance, remade an Irish national identity formed in active opposition to the British Empire into an acknowledged constituent part of imperial governance, taming its anti-imperialism and transforming it into an updated form of British oversight. In still another instance, Jewish nationalism appeared as a potentially useful ally for the British empire in the Middle East in the form of a politically indebted European settler movement in Palestine. The increased attention the United States brought during and after the war to the question of the rights of ‘small nations’ further reinforced this sense of the potential utility of nationalism for updated forms of empire. The advantages of a world of racialized nation-states for the Allied empires, then, quickly came to seem incontrovertible, even as the fantasy of reconstructing the nineteenth century’s easy-access order also retained its allure. The eventual compromise between these two visions would be simple: open borders for goods, closed borders for people.

The peacemakers at Paris (and then at St. Germain, Trianon, Sèvres, and Lausanne) had been charged as a first task with the determination of borders in central and eastern Europe and the old Ottoman Empire as the demolition of the old land empires got underway. Their new demarcations, recommended by appointed territorial commissions made up of ‘experts’ like geographers and economists, now considered how to construct new nation-states with primary reference to raw materials and networks of trade. Hungary’s need for imported coal, for instance, formed a backdrop for its ceding of Slovakia to Czechoslovakia, a coal exporter.Footnote 46 The drawing of the border between Syria and Iraq followed intensive negotiations between the British and the French about the ownership of Iraq’s oil, with a final settlement awarding the territory of Mosul to British Iraq on the condition that France would receive a permanent 25 per cent share of Iraqi oil and the additional right to buy a quarter of the oil shipped through French-controlled territory.Footnote 47 In Transylvania, the assignment of the region to Romania was carefully designed not to disrupt the prosperity of Magyar, Jewish, and German elites and businesses there; in 1919 the French, backed by a military force stationed there, blocked the new Romanian government’s effort to nationalize foreign-owned companies. ‘There are two bastions that the bayonet of the Romanian peasant has not yet been able to conquer: industry and commerce,’ one Romanian observer complained. ‘More than ever before they are in the hands of our fellow citizens of another nationality.’Footnote 48 In other words, despite Keynes’ famous post-war claims that the new borders had wilfully destroyed the economies of Eastern Europe, in fact the territorial commissions mostly put into place systems that reinforced older central and eastern European trade patterns and ensured continued access for foreign interests.Footnote 49 The simultaneous carving up of the Middle East into national ‘mandate’ states likewise followed on resource-related rationales, particularly those related to oil.Footnote 50

Even as the post-war commissions worked to maintain the openness of foreign trade and mechanisms of foreign ownership, though, the League was committing to strict controls over the movement of workers – making use of concepts of nationalism to defend borders put in place for quite other reasons. ‘Recruiting of bodies of workers … should not be permitted,’ the ILO declared in one of its earliest recommendations, ‘except by mutual agreement between the countries interested and after consultation with employers and workers in each country in the industries concerned.’Footnote 51 It was clear to all concerned that control over the roiling population politics of the newly divided territories of eastern Europe, the Balkans, and the Arab Eastern Mediterranean was key to accomplishing the Allied goal of an ordered map of ethnically defined nation-states whose resources were broadly under the control of, or at least permanently accessible to, the imperial powers.

The Question of Minorities

Such international control over both goods and people required a new set of practical tools, legal and institutional frameworks, and political justifications. The narrative of ‘minority protection’ played a crucial role in the construction and legitimization of procedural methods for retaining Allied oversight over populations within theoretically sovereign states.

From its inception, the League was assigned responsibility for the protection of communities newly designated as ‘minorities’ in post-war states whose territorial bounds had been redefined. Poland, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, Albania, Lithuania, Estonia, Iraq, and Latvia all signed treaties guaranteeing minority protections with the Allied powers; Austria, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Turkey were subject to similar minority protections regimes enshrined in the broader treaties of Saint-Germain, Neuilly, Trianon, and Sèvres. These guaranteed minorities’ rights to acquire citizenship; to equal treatment including access to public office; to use minority languages and establish and maintain cultural institutions; and to access a proportional share of public money for purposes like education.

It was immediately evident to observers from across the political spectrum that in actuality this minority protection regime would do next to nothing to advance the welfare of Hungarians in Romania or Germans in Czechoslovakia. The League’s Minorities Section, housed in the Secretariat, was charged with receiving petitions that alleged infractions of the treaties with respect to minorities – the only direct route to the League for any minority complaints. If the section determined that the petition was ‘receivable’ – a standard rarely metFootnote 52 – it was passed on to the relevant state, which could offer a rebuttal. Then, a committee made up of League Council members would discuss the case; if it had merit, the League Council would attempt to reach a consensus with a representative of the offending state. This system, such as it was, was clearly designed to ensure that vanishingly few cases would reach the Council, and even fewer would see any kind of redress.

What, then, was the real purpose of the Minorities Section and the broader promotion of League responsibility for minority rights? In the first instance, it represented a reinvention of nineteenth-century schemes that had premised European commercial, political, and military intervention in the old Ottoman realms on the fiction of ‘protecting’ certain Christian communities there, particularly Armenians. The Treaty of Berlin, signed in 1878, tied the rights of foreign corporations in the Ottoman state to ‘religious liberty’ for minorities and appointed the Great Powers ‘superintendents’ of their efforts. The independence of Serbia, Montenegro, and Romania were also premised on parallel guarantees for foreign ‘traders’ and local ‘freedom of all forms of worship’. Now, the minority treaties did the same thing: ‘The Great Powers … lay down conditions on which they transfer the territories to such State,’ the treaty for Poland ran. ‘In the future no distinction shall be made between citizens in consequence of difference of race, religion, or language … In addition to this we have provision by which Poland undertakes not to make any discrimination against the commerce of any of the Allied and Associated Powers.’Footnote 53 In other words, the idea that the rights of certain religious communities could serve as an entrée for privileged forms of European commercial presence was an old imperial practice, even if the neologism of minority gave it some new and modern valences.Footnote 54

Second, the Minorities Section provided the League with a venue for outlining a hierarchy of state sovereignty: there were some states whose minorities needed no protections, and others who – ostensibly because of their civilizational stage – had to be firmly bound by such guarantees. This differentiation aroused fury in the targeted states, whose representatives fully understood the ramifications of this kind of monitoring. As the Romanian representative to the League protested, the minorities treaties established ‘two categories of countries – countries of the first class, which, in spite of having small groups of minorities, were placed under no obligations; and countries of the second class, which had been obliged to assume extremely onerous obligations.’Footnote 55 (This distinction mirrored practices in the economic sphere, as many of the same countries were finding themselves subject to punishing regimes of austerity as a condition of currency-stabilizing loans.) The minorities system served to reinforce a global order in which some nations would have to accept substantial external interventions as a price of their territory. As the Lithuanian-born jurist Jacob Robinson put it, ‘In the Versailles peace system, the minorities provisions constituted a corollary and corrective to the principle of national self-determination.’Footnote 56

Finally, as historian Carolyn Biltoft points out, the section explicitly conceived of the petitions it received as ‘informational’ rather than actionable; they provided ‘a source of intelligence, observation, and intervention into territories and became a route for protecting certain geopolitical interests, a kind of proxy imperial command center’.Footnote 57 In other words, the Minorities Section’s collection of petitions it never intended to consider seriously made it into an information-gathering agency for the Allied powers interested in maintaining access to information about affected states’ conditions and resources while limiting Russian, Turkish, and German access to the same. The data it gathered could be put to any number of purposes by the ‘technical’ bodies of the League, concerned with matters of investment, development, and resources.

Refugees and ‘Humanitarianism’

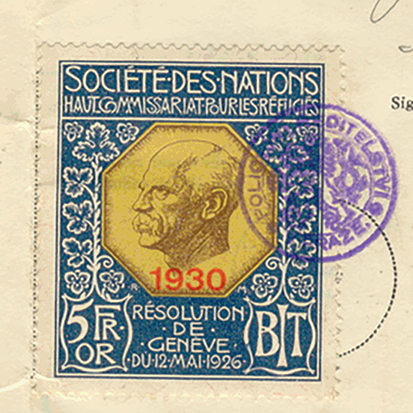

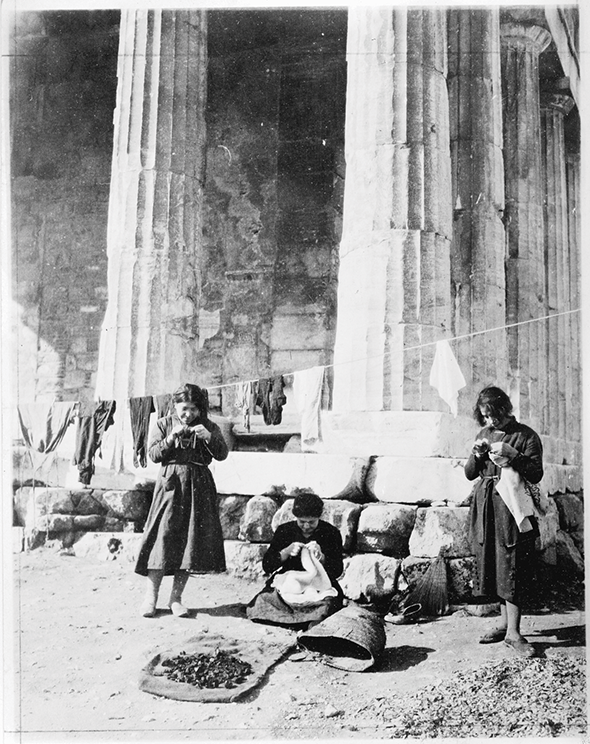

In this moment of rising nationalisms and hardening borders, then, the issue of mass displacement loomed large at the League, where contradictory interests jostled around the question of settling the war’s refugees. In the first instance, most of the displaced whom the League understood as an international problem were ‘White Russians’, people driven from Bolshevik territory through some association with tsarist interests and/or participation in the White Army. Russian refugees of this sort were not just a site of upheaval and uncertainty for the emerging post-war nation-states of central and eastern Europe; they also stood as a symbol of the political struggle between an emergent Soviet Bolshevism and the liberal-imperial political order of Western Europe and North America. Given these ideological stakes, we should perhaps be unsurprised that the first efforts to do something about the hundreds of thousands of refugees scattered around eastern and central Europe approached the issue as a problem of labour. In 1921 a collection of relief organizations, including the Red Cross and Save the Children as well as some Russian agencies, approached the newly constituted International Labour Organization with a plan to solve the issue of displacement by putting refugees back to work (see Figure 4). The League agreed that mass displacement was clearly correlated with issues of post-war labour distribution and that those dislocated by Bolshevism should be rehabilitated primarily through the liberal internationalist provision of gainful employment.

Figure 4 In March 1920, the Red Cross reported that ‘About thirty children who got lost from their parents during the rush of refugees to leave the doomed city of Novorossisk, in South Russia found themselves well taken care of. They were all gathered together and taken to the Crimea by the American Red Cross on the relief ship Sangammon. This picture shows some of the children in charge of Lieut. L.M. Foster, of Chicago. Many of the children were restored to their parents after reaching the Crimea, while those whose parents could not be located were taken to the Red Cross colony on the island of Proti where they are being well cared for.’

Such a task offered new legitimacy to the League, which presented itself as a novel agency with an unchallenged and unparalleled capacity to settle such post-war issues. The League, Red Cross president Gustave Ador declared happily, was ‘the only supranational political authority capable of solving a problem which was beyond the power of exclusively humanitarian organizations’.Footnote 58 In September of 1921, a Norwegian former polar explorer turned diplomat named Fridjtof Nansen accepted a new position at the League of Nations: High Commissioner for Russian Refugees. His task was not just to resettle refugees who were increasingly viewed as incendiary elements in the already unstable post-war European landscape but to mould them into object lessons in anti-Bolshevism, a task being taken up in more general terms by the ILO. As the American commentator James Shotwell put it, ‘The Allied Governments had to offer to labor some definite and formal recognition at the very opening of the Conference … to prove to the workers of the world that the principles of social justice might be established under the capitalist system.’Footnote 59

Selling the idea of allowing refugees in as workers, though, proved difficult. The idea that sovereign states might have the right to bar entry to foreigners was not well established prior to this period; indeed, as late as 1914 there was no legal consensus in Europe around this question.Footnote 60 But the early 1920s became a moment of near-total border closure in Britain, much of Western Europe, the Soviet Union, and – arguably with greatest effect – the United States, following decades in which some 97 per cent of immigrants entering the United States through Ellis Island were admitted without objection. In the United Kingdom, efforts to keep Eastern European Jews out had begun to gather momentum with the Aliens Act of 1905 and were now solidifying into more general restrictions. In the United States, the Secretary of State declared that a new circumspection was in order: ‘Our restriction on immigration should be so rigid that it would be impossible for most of these people to enter the United States.’Footnote 61 In the Soviet Union, the denationalization of ‘White Russian’ refugees went hand-in-hand with the closure of its (still emerging) borders, a scheme intended more to prevent emigration than immigration but that also had the effect of disallowing refugee return. Even in Latin America, long considered a space for possible migration and a safety valve for ‘surplus’ populations, governments were beginning to express doubts about the acceptance of large numbers of migrants and construct new barriers to entry.

It was in this context, then, that Nansen constructed a different plan: not one of integration or citizenship but of temporary residence premised mainly on employment. The so-called Nansen Passport was a new type of document, emerging at more or less the same time as the more general and increasingly standardized passport regime. Sixteen signatory governments agreed to issue identification documents to refugees within their borders, who would henceforth generally have permission (which could, however, be denied without explanation) to move through these countries in search of work. The participating states were not bound by this agreement, which in any case offered nothing in the way of access to citizenship. Initially, these were designed solely for personnes d’origine russe and were valid for a single year at a time. If the bearer acquired another nationality, the Nansen Passport would be rendered void. In time this system was expanded, though not to all displaced people; Armenian refugees became eligible for the passport in 1924, and a smaller number of Assyrians and related Christian ‘minorities’, mainly from eastern Anatolia, in 1928. There were also some extensions of its implications, with the addition of a right to a return visa in 1926 and the provision of certain refugee services via the League (certification of identity, offering character testimony, and recommending refugees to employers and other institutions) in 1928. The number of participating nations dropped with each addition; fifty-four states recognized the passport for Russians, but only thirty-eight for Armenians, and just thirteen for Assyrians and Chaldeans.Footnote 62

What should we make of this system? The scholarly consensus on the Nansen passport has paralleled the conversation around the League more generally, with an assessment that it represented an effortful, meaningful, and good-faith first effort to resolve the contradictions of a global system of nation-states that was producing unprecedented numbers of stateless people. Indeed, it is often regarded as the first step towards formalized international legal protections for the displaced; as historian Claudena Skran wrote long ago, ‘The beginning of international refugee law can properly be dated to the creation of the Nansen passport system.’Footnote 63 In another much-quoted phrase, Michael Marrus judged it to be a crucial and substantive legal innovation: ‘For the first time it permitted determination of the juridical status of stateless persons through a specific international agreement … [and] allowed an international agency, the High Commission, to act for those whom their countries of origin had rejected.’Footnote 64 For many decades, then, it was received as a humanitarian success that both assisted displaced people in the moment and pointed the way to later advances in refugee law and refugee rights.

To consider the validity of this interpretation, we should think about the specifics of how the Nansen Passport worked. First of all, refugees had to pay to apply for it; the charge was five gold francs. Each issuing state had its own format and its own set of information; the only feature that unified these various national iterations was the inclusion of the ‘Nansen stamp’, without which the documents would be declared useless.Footnote 65 The passports quickly became a useful source of information about the direction, numbers, and conditions of Russian refugees in various places – data that was used to try to move refugees into states nearer to the Soviet Union, particularly Poland and Finland.Footnote 66 The requirement that they had to be renewed every year allowed for heightened surveillance of refugee holders of these documents, and re-applications were often denied. The acquisition of this passport in itself guaranteed nothing to the bearer, not even the right not to be deported; it was an informal gesture of accession that could be withdrawn or not recognized at will. Still, a great number of people wanted one: the issuing countries produced some four hundred and fifty thousand Nansen passports over the course of the program’s life.

There were some ironies embedded in the outcomes of the Nansen passport system. In the first instance, the League itself, despite its developing commitment to the concept of borders and the political framework of the sovereign nation-state, was also experimenting with ideas of return to the nineteenth-century system of open borders that had been such a crucial element of pre-war liberal internationalism. It held two international meetings on the topic of cross-border mobility, in 1920 and 1926, both of which pressed member states to abandon efforts at border control and get rid of the emerging international passport regime altogether.Footnote 67 (A resolution from the 1920 conference acknowledged that contemporary conditions made impossible ‘the total abolition of restrictions and that complete return to pre-war conditions which the Conference hopes, nevertheless, to see gradually re-established in the near future.’Footnote 68) In some respects, it is possible to imagine that when the Nansen Passport was conceived its architects were looking hopefully towards a future when statelessness would once again be an essentially meaningless category, as passports were abolished and an older freedom of movement was reinstated (see Figure 5).

Figure 5 Nansen Passport renewal stamp featuring head of Fridtjof Nansen, 1930.

In practice, though, the promulgation of the Nansen Passport helped substantially to fortify theories and practices of border control: it assumed that national sovereignty necessarily carried with it the right to restrict migrant entry, and explicitly made refugees dependent on the goodwill and/or the immediate labour needs of individual states for entrance, residence, and return. It was an outcome reinforced by the 1926 League conference on passports. ‘Braving unpopularity, but conscious of the responsibilities of the Governments represented,’ the conference’s president summed up, ‘had decided that the time was not yet ripe for the total abolition of passports throughout the world … The travellers’ passport would continue – at any rate for the present – to be the conventional inter-State permit’ – now regularized, standardized, and coordinated among states. Refugee documentation would be part of this recalibration; as the conference reported, ‘the Technical Sub-Committee had already discussed the question as to how far this subject was connected with the problem of Armenian and Russian refugees … the question of method was to be left to the Committee of Experts.’Footnote 69 Far from being a temporary expedient, the Nansen Passport had proven to be an augur: of an evermore bounded and bordered future, to be sure, but also of a world in which the mechanics, operation, and legitimization of border controls would be actively recategorized as ‘technical’ rather than political questions, removed from the hurly-burly of national electoral politics into the rarefied atmosphere of international expertise.

Expulsions and Resettlements

The League’s imperative to create and preserve national order seemed, in some instances, to require the active removal and resettlement of whole populations to ensure regional ‘security’ and provide permanent avenues for internationalist intervention. These schemes, falling somewhere between its minority protection and refugee aid regimes, sought to provide the great powers with a political landscape clearly organized around nationality, in which Western political oversight and commercial involvement would have clear and legitimized national channels. It was a goal that, in their view, fully justified the suffering such schemes inevitably caused.

The practice of internationalist removal – what British Foreign Secretary George Curzon called the ‘unmixing of peoples’Footnote 70 – had precursors, of course: most notably, the many and violent expulsions and resettlements that took place between the Balkans, the Caucasus, and Ottoman Anatolia in the second half of the nineteenth century, including proposals for population swaps. In the more immediate past, iterations of this idea had been floated at the Paris talks: by Eduard Benes, for instance, who proposed exchanging Magyars and Slovaks between Hungary and Slovakia. In 1919, the first international test of such plans came with the scheme, constructed mainly by Greek prime minister Eleutherios Venizelos, for a theoretically voluntary ‘exchange’ between Greece and Bulgaria – a scheme to which the Allies acceded fairly easily. It was a short step to the next exchange, which this time would be compulsory.