The United States has a long history of political conflicts emerging out of the shifting spatial distribution of economic activity. From the first stirrings of industry in the nineteenth century through the era of mass production in the twentieth, the country’s diverse economy fostered sectional divisions over national policy. Today, another revolution in economic and political geography is taking place – the shift from an industrial to a knowledge economy. This transformation is feeding both economic polarization (between advantaged and disadvantaged places) and political polarization (between “red” Republican-leaning jurisdictions and “blue” Democratic-leaning ones). As a result, each party is increasingly drawing support from areas with distinct economic needs based on their place within the knowledge economy.

We call these differing needs “place-based economic interests” (PBEIs) – the interests of voters that emerge out of their local economic contexts. In this chapter, we investigate the extent to which they are reshaping the priorities and performance of the nation’s two major parties. The basic geographic divide on which our analysis centers is between metropolitan areas that have thrived in the knowledge economy and rural and exurban areas (hereafter, “nonmetro” areas) that have not. Metro America is, of course, increasingly blue, while nonmetro America is increasingly red. However, both have distinct economic needs that require active national policy, albeit of a different form. The question is whether those needs are being articulated and met within each party’s coalition and the US policy process as a whole.

Like other chapters in this volume, then, we are interested in the quality of representation. Our distinctive focus, however, is on the representation of voter interests rooted in geospatially differing economic circumstances – an approach we explain further in the next section. We consider this a revealing area of focus for at least three reasons. First, the parties are rapidly becoming more sectionally distinct, and these sectional divides are associated with powerful economic forces that have reshaped the geography of US prosperity, as well as the social, racial, ethnic, and economic character of both metro and nonmetro America. Second, these forces have raised the stakes for voters, whose health, income, well-being, and opportunities are increasingly connected to where they live. Finally, key features of the American political system – particularly federalism, single-member districts, and a territorially based Senate and Electoral College – are widely seen to encourage responsiveness to such place-based interests. Indeed, sectional economic coalitions have been among the most powerful forces animating US federal policymaking in the past (Bensel Reference Bensel1984; Katznelson Reference Katznelson2013; Sanders Reference Sanders1999; Schickler Reference Schickler2016). To use a national security metaphor, American political institutions are well designed to “stovepipe” local demands up to higher levels of government. In short, there are compelling reasons to expect that the knowledge economy is reshaping voters’ PBEIs and equally compelling reasons to expect that these shifting PBEIs are reshaping national representation.

Despite these strong expectations, however, we find that PBEIs are strikingly underrepresented in contemporary American politics. The knowledge economy has wrought enormous changes. Yet we find little evidence that the PBEIs it has generated are strongly reflected in either overall policy outcomes or the stances of the parties. In a variety of ways, national policymakers are failing to provide robust support for the expansion of the knowledge economy. Nor have the parties reoriented around the differing PBEIs of their geographic bases as expected. The sectionalism that has animated politics and policy in the American political past seems more often muted or puzzlingly distorted in the American political present.

Far from mirroring local economic interests, we find that each party has failed to respond to a fundamental set of PBEIs associated with core voters within its coalition. Against expectations, national Republicans have failed to reorient their economic agenda around the needs of red jurisdictions that would benefit from increased transfers from blue jurisdictions. Instead, they have placed priority on lavish tax cuts favorable to corporations and the affluent that offer little to these areas. Also against expectations, national Democrats have proved strikingly willing to promote policies that redistribute resources away from blue places that vote for them and toward red places that do not. Meanwhile, they have largely left blue jurisdictions to cope on their own with the huge collective action problems that plague urban knowledge hubs, particularly the problem of affordable housing, which hurts both metro economies and core Democratic voters.

Thus, each party’s economic priorities exhibit strong sectional disconnects, which we term the “red PBEI paradox” and “blue PBEI paradox,” respectively. These two paradoxes may seem very different from each other, and in important respects they are. Yet they also reflect the same underlying reality: while both blue metro areas and red nonmetro areas need federal help to overcome problems that cannot be tackled through localized action alone, the party allied with each of these respective locations has shown limited inclination to pursue that course, despite high costs of inaction to its core voters.

In neither case, we argue, is the main reason for the disconnect that these voters have failed to recognize their economic interests. Confusion, misdirection, and motivated reasoning are rife, but there is ample evidence of voter dissatisfaction with the status quo and desire for a more PBEI-consistent course. Instead, we point to the ways in which the PBEIs associated with each party’s geographic base are refracted through a set of “filters” that are historically and/or comparatively distinct. Three filters loom large: (1) the increasing antimetro and status quo biases of American political institutions; (2) the nationalization of US party coalitions, including the intense organized interests allied with each party; and (3) the path-dependent character of America’s unusually decentralized and fiscally fragmented social and economic policies.

Together, these institutional, party, and policy filters mute voters’ expression of PBEIs, limit the extent to which these PBEIs have reshaped party agendas, and reduce the degree to which any shifts in party agendas have been reflected in public policy. Crucially, these filters operate on both the “supply” and “demand” sides of representation. Thus, for example, the nationalization of party coalitions has facilitated the agenda control of party elites and these elites in turn have shaped the way in which voters assess parties, candidates, and policies. On both sides of the partisan divide, we shall see, elites have offered bundles of appeals that are relatively unresponsive to PBEIs, with the disconnect particularly striking on the GOP side, where “second dimension” issues of cultural and racial identity have loomed large.

In the next section, we expand on our approach to representation and then draw out the implications of the US transition to the knowledge economy for PBEIs, building on recent influential accounts. Having established a set of grounded expectations, we turn to our core task: explaining why these expectations have not been met. To do so, we first lay out the red and blue PBEI paradoxes and then our concept of filters. Finally, we show how these filters help explain the puzzling (non)response to geographic economic polarization. We conclude by drawing out some of the broader lessons of our account for the study of representation.

The Representation of Shifting PBEIs

The approach we take to representation in this chapter departs from that employed by most studies of representation, especially within the subfield of American politics.Footnote 1 Thus, we start with a brief discussion of its logic.

Filtered vs. Unfiltered Approaches to Representation

We offer what might be called a “filtered” approach to representation. We start with a set of previously theorized and empirically studied citizen interests – in this case, PBEIs – and see how well they are represented. Because we find they are underrepresented, we propose a set of explanations focused on key filtering features of the representative process. We see the enumeration of these filters as our central contribution: a means of understanding why some citizen interests (and not just PBEIs) are stovepiped into national politics while others are not.

By contrast, most students of representation offer an “unfiltered” view of representation. They start with some measure of voters’ preferences based on opinion surveys and then map those views onto some measures of politicians’ or parties’ stances. A common finding is that, at least in critical contested races, voters punish politicians with extreme stances, suggesting that the “electoral connection” (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974) is strong (see, e.g., Hall Reference Hall2015).

As the contributions to this volume show, this approach has become more sophisticated and multifaceted (and, in the process, more skeptical about the electoral connection). Among other things, scholars are now attentive to differences in voters’ opinions across class lines and to the differential responsiveness of politicians to richer voters relative to poorer ones (Gilens Reference Gilens2012). They are also more attuned to the biases and limits of voter awareness, including the strong filtering effects of the media (as in Mathews, Hicks, and Jacobs’s chapter for this volume). And they are now more likely to judge representation by looking at policy outcomes, rather than broad measures of ideological alignment between voters and elected officials.

Still, there remains a serious gap between what these analyses can show and what students of representation aim to know. At its core, representation concerns whether citizens have control over governance: the things that government does and doesn’t do to shape people’s lives. But most studies of representation pay only limited attention to governance. Even when the outcome of interest is public policy, investigations are limited to asking whether policies reflect the expressed views of voters on those policy issues and positions that prior surveys have covered. Of course, this means that many issues and positions are never examined because they failed either to make it high on the political agenda or to elicit the interest of pollsters. Moreover, this approach implicitly assumes that all issues are of equal weight to voters and equal impact on society, when in fact some are far more valued, consequential, or both.

As a result, the dominant approach to representation has little to say about a fundamental feature of representation: agenda setting – which issues and alternatives get on the agenda and which do not. As E.E. Schattschneider (Reference Schattschneider1960: 71) famously put it, a central aspect of politics is the process by which “some issues are organized into politics while others are organized out.” Even if we see congruence between opinion and policy, we still need to know whether the issues on the agenda are those citizens care about and the alternatives considered are those citizens prefer (on congruence, see Bartels’s chapter). Indeed, we might see congruence even though very few of the policy shifts that citizens want actually occur, either because the preferred shifts weren’t the focus of surveys or because the few changes that did happen were popular.Footnote 2

A last thorny question concerns what public opinion polls tell us about what citizens want. We will not belabor these issues, which are discussed extensively in other chapters in this volume. Suffice it to say that opinion polls provide only a partial and distorted picture of citizen preferences. Preferences, in turn, may be considerably removed from what scholars call “interests” (in Dahl’s influential formulation [1989], “whatever that person would choose with fullest attainable understanding of the experience resulting from that choice and its most relevant alternatives”). Whether we call these underlying demands “interests” or “enlightened preferences” (Bartels Reference Bartels1996b), they may be quite distinct from what surveys end up measuring.

Without minimizing the challenges involved, we think there is value in starting from a different place. Our concept of PBEIs is meant to capture one set of citizen interests that have the potential to reshape governance. Indeed, as we discuss in the next section, prominent scholars have argued that voters on both the left and right are developing a new set of priorities rooted in their spatial relationship to the metro-oriented knowledge economy. In part because existing scholarship has highlighted PBEIs, we are able to form research-backed expectations about how they are likely to evolve in the knowledge economy. This in turn makes it easier for us to investigate whether these key interests make the transition into governance without assuming that all issues of concern to citizens make it high onto the agenda (or find expression in reliable surveys). However, we see PBEIs as just one area – albeit an important one given recent economic changes – where a filtered approach can deepen our understanding of patterns of representation in rich democracies.

The Knowledge Economy and PBEIs

The United States is on the leading edge of the affluent world’s transition from a “Fordist” economy built around manufacturing to a “post-Fordist” knowledge economy (often shorthanded as KE). At the heart of this reorganization is the increased prominence of metropolitan areas – cities and their suburbs. Value creation and economic opportunity are increasingly concentrated in favorably placed urban agglomerations (Moretti Reference Moretti2013).

The flip side of this transformation is the relative economic decline of locations far from these agglomerations. This decline is associated with import competition and deindustrialization, as well as the consolidation of a wide range of enterprises that once supported nonurban communities, from corner stores to factories. For workers and communities lacking the human and physical capital to compete effectively in the KE, the toll has been massive.

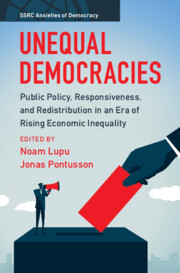

A vivid change illustrates the broader trend. Traditionally, economists expected to see convergence in living standards within an economic union. For most of the twentieth century, the American political economy met this expectation, as incomes in the nation’s poorest states steadily made up ground. Around 1980, however, a century-old trend of convergence in state incomes stalled (see Figure 5.1). Between 1997 and 2018, real GDP per capita actually diverged across the states (Ram Reference Ram2021) – a stark departure from as recently as 1977–1997. As noted, other indicators of well-being have also diverged between metro and nonmetro areas. Between 2010 and 2019, for example, Americans living in rural areas of the country experienced an unprecedented decline in life expectancy, while urban areas experienced continued gains (Abrams et al. Reference Abrams, Myrskylä and Mehta2021).

Figure 5.1 The end of state economic convergence in the United States

Equally striking are the changes in political geography that have accompanied this shift. To a degree unparalleled in American political history, the population density of a locale now reveals its partisan affiliation: the denser the community, the higher the vote share for the Democratic Party (Rodden Reference Rodden2019). More and more, the metro/nonmetro divide that cleaves the economy also cleaves the parties (Cramer Reference Cramer2016; Gimpel et al. Reference Gimpel, Lovin, Moy and Reeves2020). One result is that the American political map looks remarkably fixed from election to election (Hopkins Reference Hopkins2017). There are not just fewer swing voters; there are fewer swing places.

In short, the rise of the KE constitutes a profound political-economic rupture. It brings with it not just a radical reorganization of economic space, but also a radical transformation of the association between place and partisanship. We should expect, then, that it has also raised the salience and stakes of conflicts over PBEIs. As scholars of American political development have long argued, the nation’s territorially based electoral and governing institutions foster the representation of spatially generated economic interests. “Sectionally-based political conflict,” in the words of Bensel (Reference Bensel1984), “constitutes the most massive and complex fact in American politics and history.” This “fact” powerfully shaped partisan dynamics and domestic policy outcomes in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Bensel Reference Bensel1984; Sanders Reference Sanders1999). Later in the twentieth century, Southern economic interests fused with the defense of white supremacy to forge a heightened sectional divide that shaped nearly all features of national politics (Katznelson Reference Katznelson2013). In each case, the American institutions of federalism, single-member districts, and a state-based Senate and Electoral College magnified the salience of PBEIs and facilitated their stovepiping into party positions and public policy.

It is not just these current and historical realities that provide grounds for expecting new voter and party cleavages rooted in PBEIs. In addition, prominent political analysts have also voiced such expectations. In the next section, we consider these new theoretical and empirical accounts, which offer two basic sorts of arguments: (1) a median-voter-style argument in which the PBEIs of pivotal voters are reflected in overall policy outcomes; and (2) a distributional-conflict-style argument in which clashing parties come to represent the differing PBEIs of their core voters. These accounts identify PBEIs resulting from the knowledge economy, link them to shifting voter behavior, and argue that they are driving key policy outcomes (argument 1) or partisan dynamics (argument 2). The expectations they provide are logical, rooted in present circumstances, and consistent with the long history of American sectionalism. They are also, for the most part, not borne out by contemporary American politics.

Pivotal Voters and the Knowledge Economy

Surely the most ambitious effort to chart the politics of the KE is Iversen and Soskice’s (Reference Iversen and Soskice2019). Comparing rich democracies, they argue that the knowledge economy creates a distinct set of PBEIs based on the role of urban agglomerations, and that these interests are expressed by “decisive voters” who are part of (or aspire to be part of) this new arrangement. In response, governing parties gravitate toward policies that support the KE.

The crucial policies are those supporting knowledge hubs that anchor the high value-added sectors of the economy, according to Iversen and Soskice. Workers and firms in dynamic metro areas need a continuing supply of skilled workers, public investments, and risk-tolerant capital. They also need to embrace the cultural, racial, and ethnic diversity that characterizes high-growth metros and is essential to innovation and growth. Perhaps most important, they need help coping with the collective action challenges associated with population density (Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2019; Soskice Reference Soskice, Jacob, Hertel-Fernandez, Pierson and Thelen2022), including congestion, lack of affordable and available housing, and inadequate access to high-quality education. For reasons to be discussed later, a good share of this help must come from higher levels of government.

Iversen and Soskice (Reference Iversen and Soskice2019: 12) make fairly strong claims about representation. However, both together and separately, they have noted that this optimistic story may falter in the United States. There, the deep inequality of opportunity created by geographic divergence and economic segregation may provide fertile ground for a populist backlash. Meanwhile, the US system of territorial representation, with its strong antimetro bias, may give this backlash coalition disproportionate influence, as well as make it difficult to deliver concentrated spatial benefits to support agglomerations, however large their positive spillover effects.

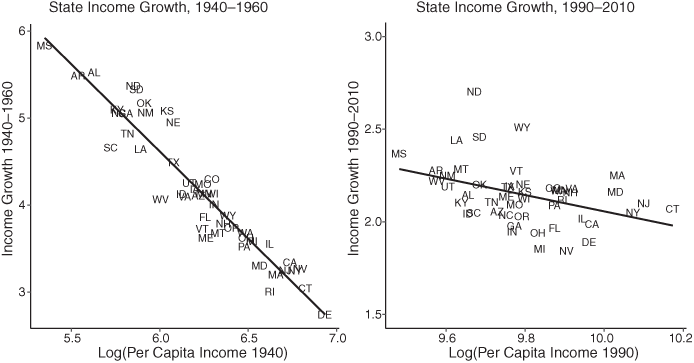

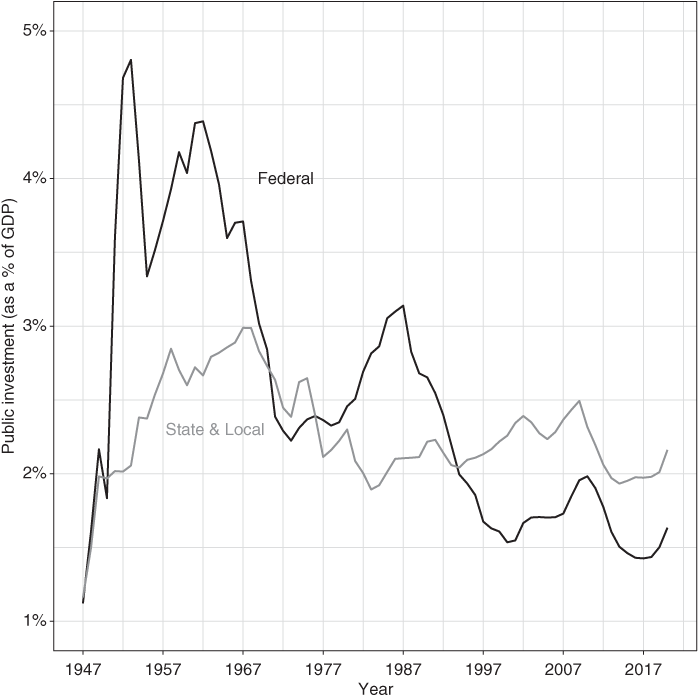

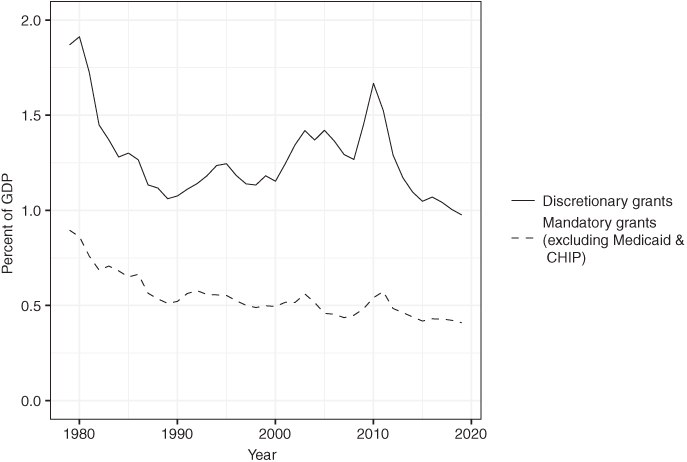

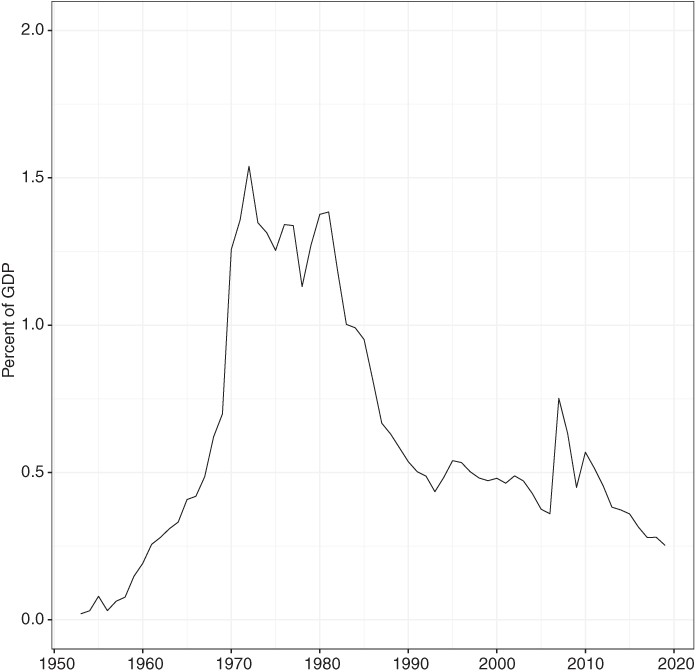

These worries appear warranted. Figures 5.2 and 5.3 summarize several pieces of relevant evidence. Figure 5.2 shows that public investment – spending on infrastructure, R&D, education, and training at all levels of government – is at its lowest point in over sixty years. Figure 5.3 shows that federal spending on cities is also starkly down. The data can be parsed in many ways, but none suggest a major response to metro PBEIs in the knowledge economy.

Figure 5.2 Gross public investment in the United States

Figure 5.3 Federal aid to the thirty-four biggest US cities

Notes: Chart line connecting black dots represents annual average (not sum) transfer to group of thirty-four biggest cities.

Perhaps, however, we are looking for the representation of PBEIs in the wrong place. The parties are responsive, but not to the PBEIs of pivotal voters but to the PBEIs of their geographic bases. This is the second type of argument introduced earlier: parties are in conflict over PBEIs, based on the differing sectional interests of their core voters. We now turn to this second model.

Partisan Conflict and the Knowledge Economy

In Iversen and Soskice’s argument, governing parties face pressure to support the knowledge economy regardless of partisan hue. In arguments reviewed in this section, by contrast, competing parties represent differing spatially generated interests. This work dovetails with a large body of work on American politics that emphasizes the local economic roots of legislative representation (e.g., Becher et al. Reference Becher, Stegmueller and Kaeppner2018). Yet it goes beyond that focus by linking overall patterns of party competition to the shifting PBEIs emerging in the knowledge economy.

Rodden (Reference Rodden2019), for example, argues that the territorial basis of US representation has accentuated partisan conflict over PBEIs. Much attention has focused on Rodden’s analysis of the antimetro bias that accompanies single-member districts (a bias we discuss later in this chapter). Equally important, however, is his argument that the parties have realigned around the “odd bundles of policies [that] came together because of economic and political geography. The Democrats … have evolved into a diverse collection of urban interest groups, and the Republicans into an assemblage of exurban and rural interests” (Rodden Reference Rodden2019: 9).

Ansell and Gingrich (Reference Ansell, Gingrich, Hacker, Hertel-Fernandez, Pierson and Thelen2022) offer a complementary analysis focused on the nature of those “urban” and “exurban and rural” interests. Like Rodden, they argue that there is a strong tendency for the American political system to stovepipe PBEIs into national politics. In contrast to many European systems, the American system encourages spatially contiguous coalitions. Voters in PR systems do not need to form coalitions that can win local majorities, so they can support (smaller) parties that draw diffuse support from like-minded voters across the country. United States voter coalitions are instead territorially based and, according to Ansell and Gingrich, reflect the growing divide between the PBEIs of rising and declining locations.

Ansell and Gingrich are helpfully specific about what these PBEIs should be. They argue that Democrats, as part of a cross-class metro coalition, should become more favorable to policy bundles that include local redistribution (what they call “decommodification”) to hold their diverse coalition together. The same voters, however, should become less favorable to policies that allocate resources beyond metro areas (what they call “deconcentration”). Thus, even relatively affluent Democrats should embrace decommodification within metro blue America, but resist shifting resources toward nonmetro red America. In contrast, nonmetro voters – that is, Republicans – should favor such deconcentration, since it will reward their economically struggling territories. As we will discuss later, this last expectation is especially plausible given that incomes are higher in blue areas, so Democratic rather than Republican voters will finance the bulk of these benefits.Footnote 3

These are expectations about voter preferences, but like Iversen and Soskice and Rodden, Ansell and Gingrich suggest the parties will reshape their national party priorities in response. Indeed, a critical implication of all of these accounts is that both metro and nonmetro regions require policy supports from higher levels of governing authority. This is obviously true for non-metro areas that lack resources: left on their own, they are acutely vulnerable to ongoing decline. But it is also true for metropolitan areas. The urban knowledge economy’s local agglomerations require extensive public good provision (for transport, education, public safety, and social services) that is vulnerable to free riding. Addressing these challenges requires federal authority (Ogorzalek Reference Ogorzalek2018). For voters and parties on both sides, then, the challenges and opportunities reflected in PBEIs require an active response from leaders at higher levels of government.

Thus, we have clear expectations: the red coalition will shift toward supporting deconcentration (interregional redistribution); the blue coalition toward decommodification (intraregional redistribution). Here, too, these strong expectations confront striking paradoxes. In the remainder of this section, we briefly lay out these paradoxes. We then turn to the institutional, partisan, and policy filters that help explain them.

The Red PBEI Paradox

Red is increasingly the color of places the knowledge economy is passing by. Yet even as Republicans have become increasingly reliant on voters in nonmetro areas, national party elites have shown little inclination to transfer federal resources toward these constituencies. There are exceptions we will discuss, such as Republican support for fossil fuel extraction. The bottom line, however, is that deconcentration is almost nowhere to be seen within the GOP policy repertoire.

Instead, the signature party priority for at least three decades has been tax cuts for corporations and the rich – a goal that is unpopular even among Republican voters. These cuts have consistently offered their greatest benefits to big businesses and the super-wealthy, not rank-and-file GOP voters. Moreover, a large majority of these beneficiaries are located in blue metro areas rather than red nonmetro regions.

At the same time, Republicans have supported stark cuts in federal transfers to the states, which have fallen by roughly half since 1980 (see Figure 5.4). Given the progressive structure of federal taxes and spending, these transfers are highly favorable to nonmetro regions.Footnote 4 Republicans have also sought to cut social spending disproportionately received by voters in these regions. The most striking example is Medicaid, which GOP leaders have repeatedly sought to scale back – most recently, in early 2023, when they sought to tie Medicaid restrictions to a necessary extension of the so-called debt ceiling, a demand that threatened the first credit default in US history. In 2017, they came remarkably close to achieving even bigger cutbacks that would have been particularly devastating for nonmetro areas and red states (Levey Reference Levey2017).

Figure 5.4 Federal grants for states and localities, 1980–2020

The Blue PBEI Paradox

Blue is the color of the knowledge economy in the United States. Given the increasingly tight link between population density, KE activity, and Democratic partisanship, we should expect Democratic elites to push for policies that support metro agglomerations. Meanwhile, they should embrace decommodifying policies (i.e., local redistribution) and reject deconcentrating ones. For the most part, however, these expectations have failed to pan out too.

Like the red PBEI paradox, the blue paradox has a positive and a negative side: unexpected policies that elites support and expected ones they do not. The key example of the former is interregional redistribution in favor of red America. As the fight over the ACA suggests, it is Democrats, not Republicans, who push for bigger transfers to nonmetro regions. Democratic elites have not simply backed existing fiscal policies that favor red nonmetro areas; they have pushed to increase this pro-red tilt, both by raising rates for top taxpayers (again, located mostly in blue America) and by expanding social policies that are particularly anemic in red America. If there is a party of deconcentration, it is the metro-oriented Democratic Party – precisely the opposite of what Ansell and Gingrich anticipate.

What about the other side of the ledger: PBEI-consistent policies that have failed to materialize? Here, what stands out is the relatively low priority placed by national Democrats on the challenges facing metro hubs that cannot be solved through local action alone. The key example is housing. Dynamic metro areas face a triple crisis of unaffordability, inadequacy, and inequality. Opinion polls suggest that the skyrocketing cost of housing is a huge concern of voters living in these regions, with strong support for various kinds of federal action (Demsas Reference Demsas2021; Hart Research Associates 2019). Housing supply shortages make productive urban centers much less productive (Hsieh and Moretti Reference Hsieh and Moretti2019), shut out millions of Americans who would benefit from proximity to knowledge hubs, and impose huge costs and risks on nonaffluent residents, including the growing specter of homelessness. These are exactly the sort of local inequalities that Ansell and Gingrich style decommodification could address.

To be sure, housing affordability is a problem of “superstar cities” worldwide. Yet the breadth of the US crisis and weakness of the US federal response stand out in cross-national perspective (Le Galès and Pierson Reference Le Galès and Pierson2019). It can be seen not only in the continuing failure of national Democrats to remedy local policy failures in this area – despite stepped-up efforts to do so in 2021, which we shall discuss later – but also in trends in federal housing outlays, which have declined dramatically from historic highs even as home prices and rental costs have moved sharply the other way (see Figure 5.5).

Figure 5.5 Federal housing and urban development spending

Table 5.1 summarizes the discussion thus far. The two types of arguments we have reviewed focus on different outcomes (overall policy outcomes vs. party stances). Yet they both foresee voters reorienting around the PBEIs that accompany the emergence of the KE. As the last column indicates, these expectations appear largely unmet.

The next section considers why. We first describe our concept of filters. We then show how these filters help account for the underrepresentation of PBEIs in the contemporary era.

Table 5.1 Representation of PBEIs in the US knowledge economy

| Focus of Account | Clearest PBEI(s) | Actual Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Iversen & Soskice – pivotal voter power in the KE | ||

| Overall policy | Pivotal voters support KE investments | Declining public investment in KE |

| Ansell & Gingrich/Rodden – partisan divergence in the KE | ||

| “Red” (Republican) Coalition’s Stance | “Deconcentration” (interregional redistribution) | Red PBEI Paradox: Resistance to deconcentration; tax cuts that are the opposite of deconcentration |

| “Blue” (Democratic) Coalition’s Stance | “Decommodification” (local redistribution), not deconcentration | Blue PBEI Paradox: Support for deconcentration; weak support for decommodification, esp. re. housing |

The Filtering of PBEIs

By filters, we mean institutional, partisan, and policy structures that refract, redirect, or block the expression of citizen interests as they move through the representative process. We divide our filters into three categories: political institutions, party coalitions, and policy regimes. Although students of representation appreciate the role of political institutions, the enormous power of this filter – especially in the United States – is not always appreciated. Less widely appreciated are the filters of party coalitions and policy regimes. Yet like formal institutions, these arrangements serve to organize some issues into national policymaking and organize others out.

Political Institutions as Filters

When thinking about representation solely in the US context, it is easy to take for granted the distinctive features of American political institutions or to treat them as historical constants. We shouldn’t, especially because the biases that these institutions produce have intensified and become more consequential. We focus on two biases in particular: the bias in favor of nonmetro interests (and the party that represents them) and the bias in favor of the status quo (and the party that seeks to preserve it). Each form of bias has grown in recent decades. Each also has enormous implications for the representation of PBEIs.

The underrepresentation of metro areas emerges out of several interlocking features of American institutions. Taken together, these impose what might be called a “density tax”: the denser a population, the less well represented it is. As the metro/nonmetro divide has widened, the density tax has not only increased; it has also become more aligned with partisanship.

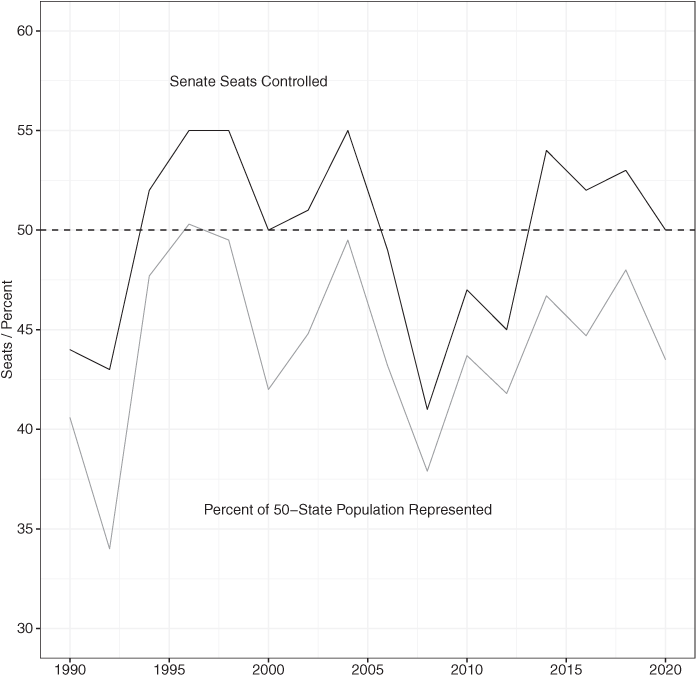

The heaviest density tax, of course, applies in the Senate, the most malapportioned upper house in the rich world. The effects include, but are not limited to, giving the GOP a substantial seat edge (see Figure 5.6). In recent decades, Republicans have frequently enjoyed a Senate majority despite representing fewer people and receiving fewer votes in Senate elections.

Figure 5.6 Republican overrepresentation in the US Senate

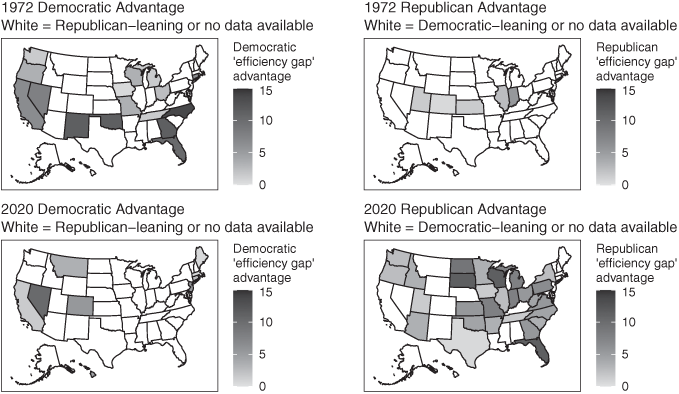

Antimetro bias is not limited to the Senate. As Rodden (Reference Rodden2019) argues, a system of single-member districts also imposes a density tax. Parties drawing their support from urban areas will be less efficient in translating votes into seats. As the parties have cleaved between metro and nonmetro areas, this tax has fallen on Democrats, awarding Republicans something like an extra dozen seats in the closely divided House (Powell, Clark, and Dube Reference Powell, Clark and Dube2020). Though there are signs the density tax has lessened as the suburbs of rich metros have become more blue, the penalty remains, and it is particularly pronounced in state legislatures. As Figure 5.7 shows, the average bias of statehouse maps toward Republicans has increased dramatically, driven by the density tax as well as the increasing frequency of GOP control over redistricting it helps produce.

Figure 5.7 Partisan skew in statehouse district maps, 1972 vs. 2020

The second crucial institutional filter is status quo bias. As students of comparative politics have long noted (Stepan and Linz Reference Stepan and Linz2011), no other affluent democracy places so many constitutional obstacles in the path of legislated policy change. In addition – and it is not a small addition – the Senate filibuster means that a supermajority of an already highly skewed institution is required to advance legislation.Footnote 5 Needing only forty-one votes, a minority that might represent less than 20 percent of the US population can block legislative action. In practice, narrow minorities block legislation, including very popular legislation, all the time.Footnote 6

Status quo bias is far from neutral. First, it empowers those who had power in the past. Existing policy can be seen as a kind of congealed influence, reflecting earlier power configurations (Moe Reference Moe2005; Pierson Reference Pierson, Fioretos, Faletti and Sheingate2016). Anything that makes these policies hard to change is likely to disadvantage those who were weakly represented in these earlier periods. This is particularly evident when it comes to racial and ethnic minorities, who are both concentrated in metro areas and now approach a majority of Democratic voters. For these voters – and the party seeking to represent them – the hurdle of American political institutions is often more like a wall.

Second, status quo bias empowers those who do not rely on national legislation to advance their interests. In general, this favors those who advocate minimalist government, or at least minimal regulation and redistribution – stances that often line up with the positions of the contemporary GOP. Like antimetro bias, the status quo bias of American institutions is favorable to one party over the other.

The interaction of these two biases draws our attention to the potential for “compounding bias,” when one institutional skew generates additional ones. As already noted, Republican state majorities, benefiting from the density tax, can gerrymander their own electoral maps, as well as those used to apportion seats in the US House. In another form of compounding bias, Republican Senators can exploit their chamber’s extreme skew to block Democratic judicial nominees, while racing their own to confirmation. The contemporary 6–3 conservative Supreme Court (which also reflects the antimetro bias of the Electoral College, which has elected two Republican presidents lacking popular vote majorities since 2000) is a vivid illustration of cumulative bias. The Court is also a far more powerful economic policymaker than often recognized, reinforcing the already-high barriers to an active response to both metro and nonmetro PBEIs. In each case, biases in one site create the capacity to enhance biases in others, even in a set of institutions expected to resist consolidations of partisan power (Pierson and Schickler Reference Pierson and Schickler2020).

We can sum up the discussion of institutional filters quickly. In the contemporary political environment, American political institutions operate in ways that greatly diminish the voice of metro interests in national policymaking, while also giving the Republican Party a representational edge that it can use to pursue its own aims or resist those of Democrats.

Party Coalitions as Filters

Party systems represent a second significant filter. Traditionally in American politics, it was assumed that national politicians would have an incentive to respond to strong place-based interests – that “all politics is local,” as Tip O’Neill famously put it. Yet as American politics has become more nationalized and polarized, local interests have faced a rockier path.

Two filtering effects are most important here. The first is the way polarization discourages elite efforts to serve local interests that are not aligned with party programs. American politics has always been based on two parties. But it has not always been based on two highly polarized and nationalized parties. In a context where two parties are not only dominant but polarized, they become powerful gatekeepers of national policymaking. Both voters and politicians are presented with increasingly binary choices, and the space to diverge from national priorities shrinks (Rodden Reference Rodden2019). Indeed, to the extent voters’ hardening allegiances are “affective” (driven by animus toward the other side), national party elites have much greater room to sidestep even deeply felt PBEIs, since voters are likely to stick with them even if they do.

At the same time that polarization decreases the scope for localized policy ventures, it increases the potential for priority setting by policy-demanding groups (Bawn et al. Reference Bawn, Cohen, Karol, Masket, Noel and Zaller2012). Groups that once might have floated between the parties now have incentives to side with one or the other, since their best opportunity for shaping policy is to enter into long-term coalitions with the party closest to them (Pierson and Schickler Reference Pierson and Schickler2020). In turn, party elites can use their increased running room with voters to serve these intense organized interests. In short, the power of resourceful party-allied groups relative to strong party identifiers is likely to increase.

It is important to emphasize that this filtering process may be quite functional for a party. Getting local issues expressed nationally may well create intraparty cleavages. Party leaders seek to institutionalize beneficial “trades” among intense allies, such as the Republican Party’s foundational trade of corporate-friendly tax cuts for conservative cultural stances. Because these deals are always vulnerable to destabilizing new issues, party leaders have strong incentives to keep such issues off the agenda. Traditionally, however, this has been difficult, which has repeatedly led to the breakdown of national issue-based coalitions (Schickler Reference Schickler2016). Parties struggled to keep divisive issues off the agenda because local politicians faced different incentives and constituencies than national ones. As this has become less true, the capacity of parties to keep disruptive local concerns off the table has grown.

We mention this last possibility because a central feature of the party filter today is that elite management of intraparty cleavages have tended to suppress, rather than foster, the representation of PBEIs. We have already mentioned the Republican Party’s prioritization of conservative pro-business policies. This has encouraged party elites to play on cultural grievances and white racial identity to mobilize voters, given that their economic priorities are largely inconsistent with nonmetro voters’ PBEIs. A very different but also very consequential intraparty cleavage has increasingly characterized the Democratic Party as it has come to rely on highly unequal metro regions. Affluent whites in these areas now largely back the Democratic Party, and as Ansell and Gingrich argue, they are relatively supportive of redistribution so long as it does not impose large costs on them. But they are much warier, we shall see, of policies that would threaten the privileges they enjoy because of local segregation and the resulting differential access to economic opportunities and public goods – a policy divide that cleaves the Democratic coalition along lines of both race and class. For Democratic party elites, this potential land mine encourages an emphasis on broader, if also less metro-beneficial, priorities.

Policy Regimes as Filters

Policy regimes represent our last and least-recognized filter. By policy regimes, we mean the inherited complex of rules and programs that determine the allocation of resources and authority in particular policy areas. While policies can, in theory, always be revised, they are highly path-dependent. Not only are those defending the status quo advantaged, but policies themselves make some changes easier to effect than others. Indeed, as the literature on “policy feedback” suggests, they shape whether certain changes are seen as possible or desirable at all, in part because they determine which allocations of valued resources are visible to voters and which are not.

Two features of the policy landscape are of particular relevance. The first is the degree to which policies automatically update to reflect changing circumstances. Revising entrenched policies is hard. Thus, default rules – whether, for example, policies expand to reflect the number of people eligible – matter enormously for how likely it is that they will continue to perform as expected, or “drift” away from their original purpose (Hacker, Pierson, and Thelen Reference Hacker, Pierson, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2015). This, we shall see, helps explain the anemic US response to the shifting contours of the KE.

The second crucial feature is the extreme decentralization of US policymaking, especially in core areas of policy that affect the knowledge economy, such as housing, land use, education, infrastructure, and policing. This extreme decentralization coexists with weak measures to even out the administrative and budget capacities of differing localities, such as fiscal equalization and revenue sharing. In cross-national perspective, American policymaking is not merely decentralized; it is decentralized in ways that accentuate inequalities across jurisdictions.

Little in these arrangements is constitutionally required. Unmentioned in the nation’s founding charter, localities are creatures of the states. Instead, these arrangements are constituted by longstanding policies that reflect the mutually reinforcing effects of path dependence and the distribution of power (Trounstine Reference Trounstine2018; Weir et al. Reference Weir, Wolman and Swanstrom2005). The resulting regime divides authority between localities and higher levels of government in ways that are both relatively invisible and pose high hurdles to positive-sum collective action.

Most notably, property-tax financing of local public goods and highly decentralized authority over land use – along with the ability of suburban communities to evade the tax and regulatory reach of cities – reinforce the influence of affluent white homeowners and give them strong incentives and ability to oppose policies that would allow less-affluent outsiders access to hoarded public goods or housing. Simultaneously, this regime makes it very hard to push these issues up to higher policy levels, where these forces of resistance would be less advantaged.

We can see how these three sets of filters play out by revisiting our two paradoxes. In the next two sections, we look again at the paradoxical positions of the Democratic and Republican Parties, showing how key filters help explain the weak (and sometimes upside-down) relationship between the stances of the parties and the PBEIs of red and blue America.

The Red PBEI Paradox Revisited

Republicans have pursued policies that offer little or nothing to their geographic bastions or even hurt these areas. Meanwhile, they have failed to pursue policies that might transfer resources toward declining red regions. The filters – particularly the institutional antimetro and status quo biases and the nature of the GOP coalition – help us understand these puzzling patterns.

The Institutional Filter

The role of the institutional filter is hard to overstate. First, as noted, it helps explain why Republicans have dominated legislatures in many states that would be closely divided, or controlled by Democrats, absent the density tax and aggressive gerrymandering. Second, at the national level, it has given Republicans a stronger hand than their popular vote totals or support for their agenda would suggest. The Senate filibuster has proved especially useful for Republicans, allowing the party to tie up governance in ways that are very hard for voters to understand or punish. In particular, it has short-circuited the kind of cross-party coalitional efforts that often undergirded sectional policy in the past.

Although our focus is on national representation, we should stress that these institutional biases also play out at the state level. In another chapter written by two of us with Grumbach (Grumbach, Hacker, and Pierson Reference Grumbach, Hacker, Pierson, Jacob, Hertel-Fernandez, Pierson and Thelen2022), we argue that GOP leaders have generally pursued policies ill-suited to a globalized knowledge economy. Indeed, we find that, controlling for prior education levels and manufacturing strength, red states that have pursued the most conservative economic policies have the lowest workforce participation, wages, and median incomes. One reason why red-state Republicans have managed to pursue such policies and still retain strong majorities is that the antimetro bias is at least as strong at the state level as at the national level.

The Party Coalition Filter

While the institutional filter is helpful in understanding Republicans’ outsized governing influence – and, in particular, their ability to block even popular policies – it is less helpful for explaining what they do with their influence. Here the party filter – the peculiar shape of the GOP’s party coalition – becomes much more important.

In brief, the Republican Party has become a national coalition uniting two sets of groups: “plutocratic” organizations, such as business lobbies and billionaire donors, that shape the party’s economic policies; and “right-wing populist” organizations, such as conservative religious groups and the National Rifle Association, that shape the party’s electoral strategies and social issue priorities. Stretching the definition of groups, the latter organizations also encompass right-wing media (which has no real counterpart on the left). The stability of this “plutocratic populist” coalition has rested in part on the willingness of leaders on the populist side – notably, those allied with the Christian right – to jettison demands for economic policies that would have benefited their mass base but were opposed by the party’s plutocratic allies (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2020).

Whenever and wherever such conflicts have arisen, the PBEIs of red America have given way to the priorities of rich America. We have already mentioned high-end tax cuts, the cornerstone of GOP economic policy. Given the spatial distribution of affluence in the United States, the direct beneficiaries of these tax cuts disproportionately reside in blue states (or abroad). Moreover, these cuts not only bypass most Republican voters. They also pose a clear fiscal threat to the GOP electorate over the long term, generating acute pressures on major social programs on which aging red-state voters disproportionately rely, including Social Security, Medicare, and Disability Insurance. In short, tax cuts not only disproportionately go to blue America; they restrict the fiscal space for “deconcentrating” initiatives that could help red America.

As noted, a version of this dynamic has already played out on healthcare. GOP “repeal and replace” plans for the Affordable Care Act (ACA) would have had a devastating impact on nonmetro America. Yet almost all national Republicans supported them. They did so in part because repealing the ACA would have allowed a rollback of the high-end taxes that provided the program’s progressive financing. Moreover, the associated Medicaid cuts could be leveraged into even deeper tax cuts in the future. Only the defection of a handful of Senate Republicans saved the ACA.

The rise of Donald Trump did not much change this dynamic. While doubling down on right-wing populism, Trump embraced both massively skewed tax cuts and the ill-fated ACA repeal. He talked about but did little to press for adequate federal spending to deal with the opioid epidemic – a core dimension of the “deaths of despair” disproportionately ravaging areas of GOP strength (Case and Deaton Reference Case and Deaton2020). Nor did he follow up on repeated promises of infrastructure or prescription drug proposals that might have helped nonmetro voters.Footnote 7

Indeed, even the one clear area of PBEI-party affinity suggests the importance of coalitional considerations. National Republicans have taken increasingly aggressive stances with respect to energy deregulation, the use of federal lands, and resistance to action on climate change. These stances have certainly helped a handful of red states (in particular Alaska, North Dakota, and Wyoming), but they have proved even more lucrative for the fossil fuel industry. Indeed, given the extreme geographic concentration of energy production in a few red states, these stances are better seen as successful rent-seeking by corporate backers of the GOP than as a viable growth strategy for red America.

Are Voters, Not Filters, the Source of the Paradox?

Before we move to the Democratic side of the story, we want to address an objection that analyses of the Republican Party like ours invariably provoke: the disconnect is not between GOP voters and their representatives; it is between GOP voters’ economic interests and how they vote. As noted, however, we do not think the explanation for the patterns we find is that GOP voters are committed to policy positions at odds with the shifting PBEIs of red America.

To be sure, voters operate in a complex environment in which party elites and allied groups provide powerful cues and no small measure of misinformation. Most people have limited understanding of policy, and partisanship and social identities heavily color what they think they know. For example, Republicans are much more likely to associate government spending with Black Americans, immigrants, and means-tested benefits (Krimmel and Radar 2021). Growing negative affect toward the other party further limits the scope for policy issues to matter in electoral politics. To this list of complications, we should add the ability of party elites to use second-dimension issues – particularly those concerning religious and racial identities – to reduce the salience of voters’ economic stances (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2020). Given the relatively homogenous racial and religious identities of GOP voters, a significant share can be motivated primarily by the cultural, racial, ethnic, and regional resentments that party elites have stoked. Indeed, a core reason we focus on PBEIs is that we want to avoid treating answers to survey questions – which necessarily incorporate these factors – as synonymous with preferences, much less interests.

Nonetheless, there is substantial evidence that Republican voters are not driving GOP economic policy and, indeed, that many of the party’s PBEI-inconsistent stances are unpopular among its own voters. For at least two decades, elite Republicans have made the combination of high-end tax cuts and sharp spending cuts the centerpiece of their fiscal plans. This was the formula embodied, for example, in Paul Ryan’s high-profile budget blueprints of the early 2010s. According to national polling, the Ryan plan lacked majority support not only among Democrats but also Republicans – and, indeed, even among GOP donors. Only among donors with annual incomes greater than $250,000 did support outweigh opposition (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2020).

More recently, the failed effort to repeal the ACA and successful effort to pass highly skewed tax cuts in 2017 were both overwhelmingly unpopular, failing to command strong support even from Republican voters. Indeed, they were the two least popular major federal initiatives considered and/or passed between 1990 and 2017 (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2020).

Perhaps most revealing, however, are state-level ballot questions. Six of the eleven red states where ballot initiatives are allowed have held votes on Medicaid expansion – a policy universally opposed by national Republican elites, as well as most state GOP leaders. Every one of these states voted in favor of Medicaid expansion. Similarly, Republican elites have strongly resisted increases in the minimum wage. Since 2006, however, eleven red states have held ballot questions to raise the state minimum. All eleven passed by very large margins.

These results suggest that red state legislatures are blocking popular initiatives, and the behavior of these legislatures only reinforces this conclusion. In Michigan, Republicans enacted their own legislation to preempt an initiative – and then promptly repealed it once the election was safely past. In Idaho, the Republican legislature responded to a successful initiative expanding Medicaid by radically restricting the initiative procedure. Missouri may well follow suit. In other red states, legislatures have ignored proposals to expand the minimum wage, among other popular initiatives.

In sum, the disconnect between the PBEIs of red America and the policy agenda of the Republican Party does not seem to be voter-driven. Instead, it bears the imprint of both America’s distinctive institutions and the particular character of the GOP coalition. Together, these simultaneously motivate nonresponsive party stances (party filter), undercut accountability (institutional filter), and increase the governing strength of the Republican Party relative to its popularity (institutional filter). The result is a nationalized interest group coalition that places top priority on business- and affluent-friendly policies regardless of their sectional impact.Footnote 8

The Blue PBEI Paradox Revisited

What we have called the blue PBEI paradox constitutes at least three puzzles. First, Democrats have not strengthened – or even sustained – KE investments. In part, this is simply a reflection of the Republican Party’s institutional edge. Nonetheless, we do not think GOP blocking can fully explain the notable fall in public investment discussed earlier.

The second and third puzzles squarely concern party stances, rather than policy outcomes: Why have national Democrats proved so eager to embrace deconcentrating policies that distribute outsized benefits to red America? And why have they proved so reluctant to address the collective action challenges of metro areas, particularly with regard to housing?

Not surprisingly, the institutional filter again looms large. However, both the character of the Democratic coalition and of the US policy regime play an important role as well.

The Institutional Filter

Both the antimetro and status quo biases of American political institutions weaken the capacity of national Democrats to update economic policies to reflect the changing needs of the knowledge economy. They do so, moreover, in ways that reflect specific features of the US policy regime we will discuss shortly. For now, the key point is that all the advantages enjoyed by the party that represents nonmetro regions and seeks to block government action are disadvantages for the party that represents metro regions and seeks to expand government action.

Moreover, these disadvantages have been growing. Urban America once enjoyed relatively strong representation in American national politics (Ogorzalek Reference Ogorzalek2018). But the density tax has been rising. Even as blue metros have gained more and more economic ground – Joe Biden won counties that produced 70 percent of US GDP in 2020 (Muro et al. Reference Muro, Byerly-Duke, You and Maxim2020) – they have lost more and more political ground. The biases of Senate apportionment, House, and state districts naturally favoring nonmetro areas, and aggressive gerrymandering and other measures (often sanctioned by stacked courts) compound to tilt the playing field farther and farther.

The eroding political clout of metro interests is not simply a reflection of the institutional filter. Urban representatives have never been a majority in the national legislature. They relied for their power on a capacity to form party coalitions with representatives from nonmetro districts. Today’s weakness of metro America also reflects profound changes in the party system.

The Party Coalition Filter

Cities have not always been solidly blue. Since the New Deal, however, their political fortunes have been tied to the national Democratic Party. During the New Deal Era, the power of the nation’s major urban centers rested on their ability to form logrolling agreements with Southern representatives, facilitated by shared partisanship (Ogorzalek Reference Ogorzalek2018). This arrangement unraveled after 1975 as the South (and eventually nonmetro districts outside it) realigned to join the Republican Party. Indeed, the earliest policy impact of this realignment was the collapse of the coalition that had supported major national urban initiatives in the 1960s and 1970s (Caraley Reference Caraley1992). Conservative Democrats (mostly from Southern and/or nonmetro places) joined the “Reagan revolution” and gutted these programs – in retrospect, an intermediate step as those electoral jurisdictions transitioned into Republican hands.

Trends since the early 1980s have further diminished the voice of cities in national policymaking. As Ogorzalek (Reference Ogorzalek2018) has argued, the Southern Democratic retreat from its New Deal alliance with cities, the growth of the suburbs, and the decline of urban political machines all weakened the strong place of cities within the party’s organized coalition. The problem is not merely that cities now have a weaker hold on the Democratic Party than they once did. Republican politicians who represent urban areas have all but vanished, and with them, the incentives to fashion cross-party compromises in support of metro PBEIs.

The character of the Democratic coalition can also help explain why Democrats in power have pursued an agenda heavy on deconcentration. To some extent, the antimetro bias of American institutions can help to explain this: due to the density tax, Democrats must reach beyond their core metro supporters to win elections. Yet it is hard to see how the institutional filter can explain why Democratic priorities envision redistributing so many resources to deeply red regions of the country where the party has no real chance of success. Nor do Democratic voters appear to be the main catalysts here. Most are probably unaware that the policies their elected officials advance entail such substantial spatial redistribution (though, unlike the case of the red state paradox, there is little sign that they would actively oppose such initiatives).

The subject requires far more research, but we would stress the role of party coalitions here, too – specifically, the role of intense policy demanders within the Democratic coalition. These include labor unions, civil rights organizations, progressive economic groups, and a variety of allied social movements. As is true on the Republican side, these organized elements of the coalition are increasingly national in their focus, increasingly working with “their” party alone, and increasingly at odds with the other party’s social and economic policies. And as is also true on the Republican side, these organized actors mostly “float above” local and regional differences: their funding comes from nationally oriented donors and foundations, their leadership and headquarters are generally based in DC, and their activities – even if sometimes focused below the national level – are rooted in their increasingly tight alliances with an increasingly nationalized party. Indeed, the Democratic Party arguably lacks some of the localized connections that have animated GOP politics in recent years (mostly on the cultural side of the Republican agenda). With the partial exception of organized labor, Democrats lack the widespread community infrastructure embodied in the Christian Right, nor have Democratic-aligned groups and movements proved as adept at using American federalism to advance their goals on a state-by-state basis (Hertel-Fernandez Reference Hertel-Fernandez2019).

The vision of party-aligned groups on the left is not just national in focus but also universal in aspiration. By this we mean they tend to advance goals – from greater ability to form a union to improved access to affordable healthcare to sustained reductions in poverty – that aim to provide greater support for low- and middle-income Americans, whatever their backgrounds and wherever they live. This vision of a universal policy floor is what you might expect from nationally focused groups with stated commitments to equality, especially the party’s mass-membership backbone: organized labor. Yet there is also a strategic rationale that seems important to many of their leaders: that the party’s multiracial coalition is best held together through appeals and proposals that center shared economic interests, rather than those specific to place, race, or other salient divides.Footnote 9 In another recent analysis (Hacker et al. Reference Hacker, Malpas, Pierson and Zacher2023), for instance, we find that both Democratic Party platforms and the tweets of recent Democratic presidents and members of Congress have overwhelmingly emphasized economic issues and universal economic policies (in contrast with Republican leaders, who emphasize cultural appeals on Twitter).

For these policy demanders, then, Ansell and Gingrich’s decommodification – downward redistribution within richer areas – is not enough. They want a generous policy floor nationwide. Given America’s highly uneven and decentralized fiscal federalism, that floor can be created only by strengthening federal redistribution in ways that offer disproportionate benefits to declining areas where supports are weak. In other words, national redistribution of the sort advocated by groups aligned with the Democratic Party tends to produce substantial deconcentration, and this deconcentration in turn tends to benefit states aligned with the Republican Party. By way of illustration, only one of the ten states with the highest ratio of federal benefits to federal taxes – that is, whose residents get back more from the federal government than they pay to it – has consistently voted for the Democratic presidential candidate since 2000 (Hawaii), while nine of the ten with the lowest ratio of federal taxes to benefits have consistently voted for the Republican candidate.Footnote 10

The Policy Filter

Many of the problems facing metro America boil down to one: cities lack the tools or authority to deal with collective action challenges they face. The erosion of federal funding for key investments in metro economies has deprived these areas of vital resources on which they once relied to manage the exigencies of urban interdependence. Of course, the institutional biases already discussed are major causes of this trend. But the structure of public policy is also implicated. As noted, different programs are more or less vulnerable to erosion over time depending on whether they require periodic legislative updating. While some federal spending programs are “mandatory” – meaning their benefits cover everyone eligible and expenditures rise automatically in response to demand – many are “discretionary” and must be reauthorized regularly. Most of the major spending programs of importance for the knowledge economy fall into the discretionary category, including support for science, education, housing, and mass transit. To grasp the full effect of the institutional filter, then, requires looking at the way existing policies privilege some kinds of policy updates while discouraging others.

The policy filter is even more clearly implicated in the final PBEI puzzle – the failure of the Democratic Party to respond adequately to the collective action challenges facing metro America, particularly with regard to housing. There is a broad consensus among economists that land use and zoning rules are the principal causes of the housing crisis. These are not national or even state policies; they are local policies, with each of the nation’s tens of thousands of local governments controlling development within its borders. This fragmented system allows suburbs to free ride on cities, magnifies the influence of affluent white homeowners (Einstein et al. Reference Einstein, Glick and Palmer2020), and empowers “home-voters” who are most likely to show up in low-visibility local elections and have extreme and intense preferences on this dimension (Marble and Nall Reference Marble and Nall2020). The result is widespread use of exclusionary zoning, inadequate affordable housing, and stark racial and economic segregation within and across jurisdictions (Trounstine Reference Trounstine2018). Much of the burden falls on those denied access to high-productivity places. But it also imposes huge costs on the most disadvantaged residents of metro America, disproportionately non-white, as well as the economy overall.

Here again, voter preferences do not seem to be the decisive factor. There is strong support for measures to provide more affordable housing (Demsas Reference Demsas2021; Hart Research Associates 2019). The problem is unfavorable political dynamics at the local level, rooted in a highly decentralized and entrenched policy regime, in which intense minority interests are privileged at the expense of broader majority interests. The result is a set of increasingly dire problems that affect millions of Democratic voters and cry out for national leadership.

Yet Democratic elites at the national level have largely failed to respond to these critical needs. To do so would require challenging localized policymaking, and that has proved something that party leaders have shown limited ability or inclination to do. The entrenchment of localized control makes the task hard to begin with. On top of that, it also creates a huge potential wedge within the Democratic coalition between affluent, white, home-owning voters and less-affluent portions of the party’s metro-based electorate. For Democrats, there are good reasons to organize this issue out of their agenda, or at least to focus on symbolic or half-hearted measures that do not threaten to activate intense potential cleavages within the party’s electorate.

In short, the institutional, party, and policy filters all help explain the underrepresentation of the PBEIs of blue metro areas, even as the knowledge economy has made their policy interests and party allegiances increasingly distinct.

Conclusion

The rise of the knowledge economy has produced a growing economic fissure between metro and nonmetro America, and this fissure has mapped closely onto the polarized divide between the Republican and Democratic parties. In a territorially organized polity, these changes might be expected to create pressures for elected officials to shift their priorities to reflect the evolving place-based interests of their constituents – a recurrent historical pattern in American politics that prominent scholars have argued is happening again today.

Despite these pressures, however, we find more refraction than reflection. There is limited sign of Iversen and Soskice’s predicted realignment of partisan competition around promotion of the knowledge economy. Indeed, the last two decades have witnessed a marked decline in policy support for the knowledge economy – a potentially fateful development.

Nor have the parties reoriented themselves toward the PBEIs of their geographic bastions as might be expected. Despite increasing reliance on nonmetro voters, the Republican Party has done little to support Ansell and Gingrich’s “deconcentration,” focusing its priorities on the demands of wealthy voters and corporate interests rather than those of its broad voting base. Instead, if there is a party backing deconcentration, it is the Democrats – driven in part by their own organized allies, who emphasize the need to raise the social policy floor in nonmetro regions. At the same time, even as the Democratic Party has come to dominate the nation’s metro agglomerations, national Democrats have failed to robustly address the hugely costly dilemmas associated with local control that threaten these blue locales’ continuing success.

To explain these paradoxes, we have argued for a greater focus on what we call “filters” – durable features of a polity that mediate the influence of citizens on governance. In asking whether PBEIs make this transit, we seek to avoid the assumption common in the prevailing filter-free view of representation that all issues of fundamental concern will become manifest in policymaking. Because of the institutional, party, and policy filters, there is no guarantee that voters will see a clear link between their electoral choices and their PBEIs, or that politicians will respond to those PBEIs even if voters articulate them. In particular, there is no guarantee that local economic interests will be stovepiped up to higher levels of government where effective action can be taken.

Our filtered approach to representation emphasizes three refracting features of contemporary American politics. First, geographic partisan polarization has accentuated longstanding biases in US political institutions that impose a density tax on voters in metro areas and privilege the policy status quo. This, in turn, has made ongoing policy adaptation to the knowledge economy difficult and shifted the partisan balance of power toward the Republican Party. Second, in an increasingly nationalized and polarized party system, the character of party coalitions is another powerful filter of local economic interests. Organized groups operating on a national scale have strong incentives to pick sides, orient their activities around national party agendas, and take advantage of parties’ increased agenda-setting power. Especially with affective partisan identities increasingly driving voter behavior – identities that map onto and have roots in racial and ethnic conflict as well as growing geographic inequality itself – party elites may well feel empowered to pursue policies with support from organized allies even when those policies are at odds with voters’ local concerns.

Finally, the distinctive structure of the US public policies weighs heavily on the representation of metro interests today. Localized control over zoning and other vital policy levers places a formidable barrier in the way of national action to support the knowledge economy and help urban agglomerations overcome collective action problems. The party filter also matters here, too, for unsettling these costly arrangements could also unsettle the Democratic Party’s alliance between the privileged and the disadvantaged and between urban and suburban residents of metro America. Thus, Democrats too face distributional tensions between the most affluent portions of their coalition and their broader voting base.

Whether those tensions can be resolved depends in part on the heated battles taking place in Washington as we write. In 2021–2022, the razor-thin Democratic majority in Congress failed to enact an ambitious package of domestic social policies. However, it did pass three bills (two with modest Republican support, one enacted on a party-line vote) that began to address the huge backlog of urban infrastructure needs and the long-term stagnation of investment in advanced R&D. It is important to recognize, though, that these new initiatives were paired with a great deal of investment in nonmetro areas, in part because the pivotal Democrat in the Senate was Joe Manchin of (rural) West Virginia. Notably, the investments envisioned so far include substantial funding for infrastructure and clean energy in red areas of the country. For example, nearly four-fifths of the clean energy investments announced by May 2023 under the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act are set to take place in Republican House districts. Meanwhile, the new House Republican majority has voted to repeal these incentives (a symbolic step, given Democratic control of the Senate, but one that could get caught up in the aforementioned debt ceiling fight). As the veteran journalist Ronald Brownstein aptly notes, “This opposition contravenes the traditional assumption that politicians almost always support the economic interests creating opportunity for their constituents.”Footnote 11

We do not think the filters we have examined completely explain this striking disconnect, much less all the patterns of representation we see. A focus on the institutional, party, and policy filters does not fully capture the role of race, for example – though distinctive elements of that role do come into view, as we hope we have shown. Nonetheless, the filters play a fundamental role in explaining why PBEIs occupy such a limited and often paradoxical place in American politics today. National party priorities cannot be simply “read off” of voters’ preferences – we need to see how they are refracted through the filters. Because of the nationalization and polarization of the parties within a distinctive electoral system, neither Democrats nor Republicans are likely to be penalized if they neglect PBEIs as they would have in the past.

To be sure, there is scope for PBEIs to come to play a larger role, and party coalitions can and do change over time. A crucial question is whether the investments being made today might bolster Democrats’ standing outside their metropolitan base, in turn pressuring Republicans to be more responsive to the PBEIs of their constituents. Another is whether organized elements of the business community that benefit from such investments might become more willing to actively back the Democratic Party and even perhaps push it to focus more on metro investments. Ultimately, the question is whether the filters will continue to dampen the incentive for US representative institutions to produce active federal policies responding to the dramatic shift in the geography of prosperity that the transition to the knowledge economy has fostered.

This is not a question for American policymakers alone. All advanced democratic societies are grappling with it in one way or another. Many of the features of the American political landscape that we highlight are unusual. Those features may well help to account for the growing cross-national evidence that the United States is a significant outlier with regard to the representation of citizen preferences in an increasingly unequal economy. Yet we believe a filtered approach to representation has relevance beyond the American case. Our hope is that this paper can contribute to the ongoing effort to consider how countries’ institutions, party systems, and policy inheritances influence the degree to which the concerns of ordinary citizens are translated into public policy.