Lights glowed brightly from the Hotel Habana Libre on the first day of January 1966. Built by Hilton seven years earlier for wealthy American tourists to enjoy the expat playground that was Havana, the building’s facade now featured hundreds of bulbs sketching an image of an outstretched arm gripping a rifle and holding a stylized globe. Thus did Fidel Castro’s regime welcome its guests to the first Tricontinental Conference uniting revolutionary Asians, Africans, and Latin Americans.Footnote 1 Hundreds of delegates from Indonesia, India, Iran, Guinea, the United Arab Republic, Kenya, China, the Soviet Union, and elsewhere filled the streets of Havana for the next two weeks. Their goal was to define a vision of Third World solidarity that could combat the threats of imperialism, colonialism, and neocolonialism that Castro saw embodied in the former life of the 25-floor casino hotel. Joining heads of state and diplomats were representatives of armed revolutionary movements from both European colonies and independent states, ranging from the Rebel Armed Forces of Guatemala (FAR) to the recently founded Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO).Footnote 2 At the center of this loose coalition of governments and activists was a radical vision of self-determination. The majority of attendees championed armed revolt, socialism, the creation of cultural and economic institutions to resist foreign domination, and a new focus on the “common enemy of North American imperialism.”Footnote 3 The Havana conference reflected a radical worldview justifying Third World revolution, which is best termed Tricontinentalism.

Secular, socialist, and militant, Tricontinentalism aimed to empower the states of Latin America, Asia, and Africa and mount a revolutionary challenge to the Euro-American dominated international system in the 1960s and 1970s. While the organizers of the Havana meeting described the conference as a continuation of the search for solidarity begun a decade earlier by Afro-Asian organizers at Bandung, they also insisted that their gathering constituted “a new stage in the common struggle.”Footnote 4 The incorporation of Latin America, heightened concern about economic neocolonialism, and a commitment to internationally contentious revolts in Vietnam, Palestine, and the Congo all demonstrated that solidarity had evolved in radical directions. No longer was it sufficient for Afro-Asian heads of state to collaborate diplomatically to denounce nuclear war and explore new forms of economic cooperation, as earlier examples of Third World cooperation had proposed.Footnote 5 A decade of mostly pro-Western coups showed the fragility of postcolonial governance as well as the rising threat of American-led interventionism. New forms of action seemed necessary.

Delegates to the Havana meeting concluded that armed revolts by stateless groups, the creation of new coalitions, and the embrace of radically socialist domestic and international agendas were necessary to defeat global imperialism and empower decolonization. Conspicuous support for this agenda came from the Soviet Union and – initially – China, both of which championed anti-imperialism, claimed linkages to and sometimes membership in the Third World, and offered aid to help balance disparities of power.Footnote 6 The Tricontinental Conference thus broke with Bandung’s self-conscious neutralism by, in the words of one organizing document, reuniting “the two currents of world revolution … the socialist revolution of October and that of the national liberation revolution.”Footnote 7 Cuba’s role as conference host was symbolic of this new unity of purpose. The agenda laid out at Havana refined and promoted a new current of anti-imperial activism that had percolated for years and would shape international affairs for a decade.

Tricontinentalism recast the Third World agenda while energizing the Cold War, but its history reveals broader dynamics of anti-imperial solidarity politics within the Global South. In an attempt to recover the complexity of the ongoing challenge to the Euro-American dominated international system, The Tricontinental Revolution: Third World Radicalism and the Cold War offers a revised framework and chronology of Third World internationalism by challenging the idea of a single, evolving movement. Third World solidarity emerged during the Cold War, as political scientist Robert Vitalis has argued, from a series of overlapping ideologies and movements that promoted different forms of cooperation as postcolonial countries grappled with political, economic, and social challenges.Footnote 8 Adjusting Vijay Prashad’s idea of a “Third World Project” pursued by the “Darker Nations,” it might be more accurate to talk of a century-long Anti-Imperial Project that existed in the overlapping goals of these diverse movements and which informed the Third World idea as it evolved in the context of the Cold War.Footnote 9 This project encompassed an array of sometimes competing ideologies and alliances that collectively hoped to achieve sufficient unity to advance the shared interests of the Global South, or the regions of Asia, Africa, and Latin America that shared historic experiences of empire, economic disparity, and resistance. Using the term “Anti-Imperial” consciously recognizes that this negative opposition to Western imperialism provided a sense of common purpose and inspired transnational cooperation, but Southern actors often diverged – sometimes dramatically – in their visions for the positive programs that would replace it. Although one ideology never triumphed, certain strands of thought rose to prominence within this Anti-Imperial Project at different points in time. From the 1960s through the late 1970s, Tricontinentalism was arguably the most influential of these competing visions, ushering in an era in which militant anti-imperialism became a prominent part of the global zeitgeist.

Tricontinentalism gained traction as a radical alternative to the relatively reformist agendas of the first generation of postcolonial leaders. In many places, these politicians inherited fractious societies while facing a hostile international system. Promises of economic development built primarily on adaptations of capitalist and socialist modernization schemes faltered as the 1960s dawned, reinforcing inequitable ties to an international commercial system upheld by Western governments and corporations. Potential allies within the Global South shared problems and interests but embraced a variety of political, ideological, and economic orientations. Superpower interventions further constrained the autonomy of the Third World actors. The sheer economic, political, and military power wielded by the United States and the Soviet Union circumscribed options for economic and political sovereignty by empowering specific socioeconomic agendas aligned with Cold War camps, sometimes undermining governments that aggressively championed independent nationalist programs.

In this setting, armed revolution and confrontational diplomacy became attractive alternatives for Third World elites frustrated by the slow pace of change. Repressed nationalists and diasporic peoples that continued to chafe under Euro-American preponderance championed aggressive, transnational responses that challenged Bandung’s emphasis on diplomatic cooperation between independent states.Footnote 10 The Cuban, Algerian, and North Vietnamese governments that came to power through armed conflict offered visions of a militant, socialist anti-imperialism.Footnote 11 Revisiting earlier ideas and associations, these and sympathetic states like Egypt spoke openly of revolution and flirted with new alliances such as the increasingly militant Afro-Asian People’s Solidarity Organization (AAPSO). By the late 1950s, the radical anti-imperialism present at the Havana conference began to differentiate itself from the neutralism of Bandung. These radical impulses gained momentum as ambitious but measured Third World programs faltered and military coups upended governments in Brazil, Ghana, and Indonesia. Scholars have recognized this shift, describing it vaguely as a “second generation” of Third World leadership and noting “the vogue of revolution in poor countries.”Footnote 12

This volume contends that Tricontinentalism provides an essential framework for understanding and analyzing this phenomenon and the era it helped define. At its core was the idea that countries in the Global South shared histories of Euro-American colonization, which gave them reason to seek coordinated, militant strategies of resistance and empowerment in the hostile context of an international system created by empires. International meetings and publications such as Tricontinental from the Havana-based Organization of Solidarity with the Peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America (OSPAAAL) became forums for revolutionaries to articulate and debate specific programs. Texts, conferences, and diplomatic exchanges integrated diverse ideas of political, economic, and cultural revolution into a common agenda inspired by and reflected in the oft-referenced armed struggles in Vietnam, Cuba, Algeria, South Africa, and elsewhere. Though Third World leaders used the term inconsistently, Tricontinentalism captures how many militant parties and movements described their visions of self-determination and national development as part of a global community of likeminded peers. This “dynamic counter-modernity,” in the words of scholar Robert J. C. Young, challenged Western imperialism at multiple levels with interrelated African, Asian, and Latinx internationalisms.Footnote 13 It also proved more attentive to the demands of a wide array of international actors than had prior iterations of the Anti-Imperial Project, articulating an expansive anti-imperialism that directed popular ire at the capitalist West and its client states in the Global South.

Given the diversity of its adherents, Tricontinentalism is best understood as a worldview. It was a way of understanding how the international system worked and laid down specific goals for marginalized, often impoverished states to achieve genuine self-determination. Eschewing strict dogmatism, this worldview led countries with similar assessments of comparable problems toward a set of best practices for achieving independence that were adapted and negotiated to address local circumstances and insecurities. The ultimate objective was the destruction of colonial and international structures favoring Western interests and their replacement with more egalitarian states and institutions. This perspective and the policy choices it suggested borrowed heavily from socialism, which invited Western reaction and threatened to pull states into the Sino-Soviet competition. The most assertive advocates adopted violence and expanded alliances with the communist powers as the logical response to Euro-American interventions. This leftward revolutionary shift effectively differentiated Tricontinental advocates from moderate postcolonial peers, creating what members argued was the vanguard of a global Third World revolt during the 1960s and 1970s.

The Historiography of Tricontinentalism

Despite its influence, Tricontinentalism remains an underappreciated concept because anti-imperial internationalism has only recently become a popular subject for scholarly study. The global history of the later twentieth century has long been dominated by the Cold War. To the extent researchers have considered the foreign relations of Third World governments, the majority have done so in terms of superpower conflict: how the great powers perceived their interests, and how actors in the ostensible periphery reacted to intervention.Footnote 14 Only in the last two decades has the international turn led scholars to seriously question this dominant narrative. Many now argue for the equal importance of decolonization, which transformed the international system by adding dozens of new states in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Scholarship initially focused on metropolitan retreat has shifted to consider how decolonization empowered the Global South to challenge the Eurocentric international system.Footnote 15 South-South alliances and material exchanges encouraged struggles for self-determination during a period of increased superpower attention to these regions.Footnote 16 So too did Southern states collaborate to establish new institutions and economic ideologies in attempts to create a fairer international system.Footnote 17 Such scholarship is informing new histories of Third World international relations and solidarities that opposed – or even predated or existed independently from – the Cold War.

Though the historiography has expanded to reflect the experience of nations from the Global South in the twentieth century, scholars are still working to understand the complex realities of Third World internationalism – its alliances, ideologies, chronologies, and terminologies. Most histories of the Third World fall into one of two categories: studies like Odd Arne Westad’s influential Global Cold War that highlight connections to the superpower conflict and others that detail the foreign relations of noteworthy countries or individuals from the Global South.Footnote 18 A smaller third category considers diplomatic conferences as windows into the broad project, with an emphasis on Bandung in historical circles and Non-Aligned Movement summits in political science.Footnote 19 Although these latter works are pivotal to our understanding of politics in the Global South, Prashad’s polemical exploration of the rise and frustration of the Third World Project remains the primary overarching narrative from which many scholars draw.Footnote 20 Prashad hints at the diversity of visions that existed within the movement, but he generally describes the efforts of a continuous, if decentralized, leftist anti-imperial ideology.

In collapsing solidarity politics into a single phenomenon, Prashad and other scholars have yet to fully grapple with the diversity of the Anti-Imperial Project. This is especially true among historians, for whom an exaggerated or mythic version of Bandung and Afro-Asian solidarity orients most studies.Footnote 21 The 1955 meeting assembled twenty-nine Afro-Asian states (Map 0.1) in the Indonesian city of Bandung, where they sought collaboration in support of self-determination, economic development, and peaceful coexistence. The vague conclusions of the final statement reflect the fact it was a relatively staid gathering of mostly independent Asian countries, but the “Bandung Spirit” promised much more. Contemporary reporters (and later revolutionaries) cited Bandung to critique an expansive list of global inequalities between and within nations that sometimes diverged from the actual proceedings. Thus, the conference earned a symbolic association with key issues of Third World transnationalism and revolution that more closely align with other iterations of the Anti-Imperial Project such as Tricontinentalism.Footnote 22 As a result, even historians of African revolutions and nonstate movements – the vast majority of which had barely a presence at Bandung – feel obliged to connect their studies to the 1955 conference.Footnote 23

Map 0.1 Official delegations to the Bandung conference, April 1955

Twenty-seven independent states sent official delegations as did Sudan and Ghana, which were moving toward self-rule. Yemen refers to the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen.

Lost in this universalization of the Bandung Spirit are the ways Third World actors devised new forms of solidarity to confront contingent global challenges. The extended process of decolonization, Cold War interventions, the proliferation of multinational businesses, the rise of neo-capitalism, and geostrategic conflicts within the Global South all strained the inclusive vision of solidarity present at Bandung. These multiplying challenges compelled advocates of anti-imperialism to consider radical solutions. Ironically, it has been these Tricontinental elements – including an explicit militancy, vocal opposition to racism, and inclusion of transnational movements – that often typify the mythologized Bandung Spirit and give it explanatory power.Footnote 24 This conflation of both Cold War Third Worldism and the larger Anti-Imperial Project with elements specific to the radical, leftist internationalism of the 1960s obscures complex internal dynamics, not just in the radicalization of Tricontinental states after Bandung but also the mobilization of anti-imperial ideas by such diverse actors as authoritarian Brazil and Islamist Iran.Footnote 25 Many countries pursued shared goals of the Anti-Imperial Project and claimed legitimacy by citing common precedents such as Bandung. Yet because they adhered to discrete ideologies, states clashed politically and sometimes militarily even as they cooperated uneasily in ventures such as the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) or the pursuit of a New International Economic Order (NIEO).

Tricontinentalism deserves attention as a distinct worldview within the Anti-Imperial Project – one example of Vitalis’s discrete ideologies.Footnote 26 A handful of scholars have been attentive to this outlook, especially the ways in which it linked Cuban foreign policy to US radicalism.Footnote 27 But alongside this approach has emerged a broader reading of Tricontinentalism as a “framework for understanding … global, antiracist, and anti-imperialist politics,” which Besenia Rodriguez argues better explains some of the more expansive black internationalist traditions used in the United States than do ethnonationalist forms of Pan-Africanism alone.Footnote 28 Yet as Robert J. C. Young argues, Tricontinentalism drew inspiration and meaning beyond the Americas, articulating a radical challenge to the global status quo that integrated Marxism and anti-imperial nationalism. Young’s proposal that a universalized form of Tricontinentalism better explains the academic discourse of postcolonialism muddies historical relationships and timelines, but he successfully outlines a canon of radical thinkers including Mao Zedong, Frantz Fanon, Che Guevara, and Amílcar Cabral that laid its intellectual foundations. They adapted elements of Marxism to create a global vision of empire that united movements across cultures and informed a Third World “nationalist internationalism” positioning militant revolution against the systemic economic and racial inequalities created by capitalist imperialism.Footnote 29

An improved historical understanding of Tricontinentalism therefore promises to help explain both the long history of anti-imperialism and a pivotal period within the Cold War. Indeed, consideration of the ideologies and transnational solidarities built by this “second generation” of Third World leaders has been at the heart of a number of important studies over the past decade, but disciplinary silos and the challenges of multicontinental research have militated against the creation of a common vocabulary. Related phenomena that fall under the umbrella of Tricontinentalism have been variously described as radical Third World Politics (Quinn Slobodian), the Third World Left (Cynthia Young), Anti-imperialism (Jeremy Friedman), and a component of Prashad’s Third World movement.Footnote 30 Anne Garland Mahler, who wrote the first book-length history of Tricontinentalism and contributes to this volume, helps unite these various discussions by providing a globally applicable definition of the Tricontinental worldview reflected in but independent of Cuban policy. Emphasizing its roots in black internationalist thought, she describes a discourse that envisioned anti-imperial, anti-capitalist transnational solidarity “as a rehearsal for the eventual realization of a new global social relation.”Footnote 31 This volume mirrors and builds on this expansive concept of Tricontinentalism, linking it to the diverse discussion of Third World politics occurring in international history circles. It seeks to capture the wide manifestations of this phenomenon while exploring the political and diplomatic alliances it sought to create. In the process, it reveals the fraught and fluid nature of anti-imperial solidarity, and why it proved difficult to translate powerful ideas into an effective challenge to deep-seated global inequalities.

Elements of Third World Revolution

The volume explores the content and historical context of Tricontinentalism by bringing together some of the top scholars of Third World international politics. Representing a variety of disciplines, linguistic skills, and regional expertise, our contributors have written eleven intersecting case studies with an emphasis on the contributions of prominent nations and liberation groups to the Tricontinental project. Taken together, the chapters reveal how revolutionaries developed militant, anti-imperial solidarity in the 1960s and established semiformal networks to empower states and organizations from the Global South against what they regarded as an unjust world system. The book’s agenda goes beyond simply considering the 1966 Havana conference or regional internationalisms. Specific programmatic aspects united diverse polities under the umbrella of Tricontinentalism, which inspired the foreign policies of nations and movements from Southeast Asia to Latin America as well as the agendas of civil society groups in Europe and the United States. Cuba features prominently in these studies as arguably the most committed state advocate of Tricontinentalism, the home of OSPAAAL, and a consistent proponent of integrating Latin American revolutions into the Afro-Asian tradition. So too does the Cold War play a role, with the militant shift encouraged by the Sino-Soviet split empowering advocates of the socialist-inflected Tricontinental worldview even as the United States sought to contain radicalism. But the principal goal of the volume is to provide a perspective on Third World solidarity that accounts for the array of visions and policy prescriptions offered by small states and political movements seeking to assert their independence via radical anti-imperialism.

The overlapping visions revealed in each chapter enable us to see the core elements of Tricontinentalism. Although it fits within a longer Anti-Imperial Project that championed political independence and greater economic equality for Southern nations, a unique combination of elements made it distinct. First, it was militant in its goals, aiming for a wholesale restructuring of the international system that promoted complete self-determination and economic justice between global North and South. The most dramatic tool for achieving this transformation was military struggle, which became the preferred method in the 1960s for nationalists unable to evict colonial powers and foreign economic control through negotiation or United Nations (UN) mediation. While armed revolt became a kind of political totem by the 1970s, chapters in this volume show nationalists adopted militancy as a direct response to interventions by colonial and Western powers – specifically the Cold War United States. Tricontinental advocates used negotiations and economic coercion to pursue their goals, but armed revolt provided a powerful bargaining chip and necessary last resort for redressing rigid systemic inequalities.Footnote 32

Second, Tricontinentalism emphasized an expansive form of anti-imperialism. Recalling critiques of the international system proposed by earlier organizations such as the League Against Imperialism (see below), advocates opposed not only political control by European empires but also subtler forms of economic and cultural domination.Footnote 33 This agenda owed much to the centrality of a socialist-inflected worldview, which saw the international system as intertwined with a Euro-American capitalism that also explained the preponderant influence of Western culture. Regularly defined in the mid-1960s as opposition to neocolonialism, this line of thinking marked a shift from an emphasis on anti-colonialism against European metropoles to an anti-imperialism against creeping US preponderance. As Michael Goebel argues, this shift was necessary for meaningful Tricontinental solidarity; decolonization allowed Afro-Asian states to recognize and identify with the threat of dollar diplomacy that long inspired resistance in Latin America.Footnote 34 Tricontinentalism – cohering as it did in the wake of decolonization’s supposed triumph – required an ambitious program to combat pernicious forms of foreign domination that lingered in the wake of “flag” independence.

The broad definition of imperialism meant that Tricontinentalism exhibited hostility not just to states of the Global North but also to Southern governments deemed insufficiently revolutionary.Footnote 35 Participation in the Anti-Imperial Project bestowed an element of legitimacy on stateless nationalist parties throughout the twentieth century, which they used against both metropoles and political opponents when claiming authority as governments-in-waiting.Footnote 36 But the fight against neocolonialism added a new wrinkle. Rejecting Bandung’s notion of “unity in diversity” that made room for an array of states with competing ideologies, Tricontinentalism defined a loose ideological litmus test based on commitment to militant confrontation, socialist redistribution of economic wealth, and anti-imperial foreign policies. This approach defined an exclusive but ideally more unified vision of Southern solidarity. A coalition of vanguard parties and states led a movement that would grow as moderate Third World states either aligned with the ideology or suffered radical revolutions. This approach opened the door for participation by insurgent revolutionary parties to play a vital role in Tricontinentalism, opposing colonialism and occasionally Southern governments that radicals claimed were complicit with imperialism.Footnote 37

Third, the Tricontinental reading of anti-imperialism sought to wed the program of Southern sovereignty with Marxism. Anti-imperialists found common cause with the Soviet Union from its founding, but the dogmatism of international Communism and its inability to fully integrate either the national or racial questions prevented a wholesale merging of the movements. These divisions – along with Moscow’s ill-timed promotion of peaceful coexistence and China’s perception of the Soviet Union as an imperial power – fueled the Sino-Soviet split and complicated the construction of solidarity. Nonetheless, Tricontinentalism spread precisely because it sought to address problems specific to Third World states using a worldview based on Marxist structural analysis. The movement, in short, shared a sense that underdevelopment, racial inequality, and cultural marginalization grew from capitalist exploitation without accepting a single model of action or political mobilization. Tricontinentalists did not abandon European communism because most never fully adhered to it. Rather, major theorists including Castro and Cabral argued Southern states were building on earlier Communist victories by leading a new stage in the anti-imperial revolution that addressed lingering inequalities.

Most Tricontinental states defined their socialism as distinct from Soviet communism in two ways that made it better suited for the postcolonial context. First, they wedded it to the creation of sovereign nation-states that would collectively combat racism and change the international system; second, they eschewed classical definitions of class warfare in favor of a colonized (South) versus colonizer (North) mentality, wherein the colonized occupied the role of the masses and the colonizing imperialists a sort of global bourgeois.Footnote 38 This formulation allowed for a greater emphasis on national unity in the anti-imperial struggle – both before and after independence – while opening avenues for broad solidarity.Footnote 39 More problematically, it cast the small middle classes of the Third World as outsiders or minor imperialists and encouraged party leaders to dismiss even legitimate dissent as the product of external influence. The result was ideologically-based identities – both in terms of local nationalism and global anti-imperialism – that were fungible. Assimilated or educated classes in the Global South, Northern Diasporas, and even Euro-Americans could all align with the revolution, so long as they adopted sufficiently anti-imperial identifications and political programs.Footnote 40

Fourth, Tricontinentalism effectively picked sides in the Cold War but created few permanent institutions for both ideological and practical reasons. Third World nationalists were committed to non-alignment and independent foreign policies, but the communist bloc offered models for politico-economic reinvention, material assistance, and diplomatic protection from Western intervention. After early attempts to formalize a radical Third World alliance faltered due to limited resources and superpower hostility, many Tricontinental states looked East for help. Cooperation with communist countries – particularly the Soviet bloc – provided an avenue for moderating power disparities between small iconoclastic states and a Western-dominated international system hostile to revolutions. The Sino-Soviet split complicated these alliances, but competition for the preeminent role in the world revolution encouraged both communist powers to expand their involvement in the Third World.Footnote 41 Aggressive, agrarian Maoism contrasted with Soviet preferences for gradual revolution, peaceful coexistence with the United States, and orthodox Marxism. The Maoist brand of socialism influenced and more fully aligned with the Tricontinental worldview, but China’s emphasis on opposing the Soviet Union (and Moscow’s Third World allies) ultimately reduced Beijing’s influence. By contrast, the Soviet Union accommodated itself to the heterodox socialism where revolutionary movements proved effective, and industrialized Eastern countries could offer more aid than agrarian China. Radical Third World relations with Moscow were not always warm, but sufficient ideological affinities and the need for material assistance made Soviet bloc linkages vital for Cuba, Vietnam, and many African liberation movements. The result was a diplomatic balancing act, but one which leaned toward the Soviet Union by the late-1960s and developed further in the next decade.

The combination of ideological and strategic considerations explains why Tricontinentalism remained loosely organized and states non-aligned, even as they collectively leaned left. International institutions and major post-Havana conferences threatened to exacerbate Third World or Sino-Soviet tensions and could possibly invite Western intervention. This last issue highlights the reality that as much as Soviet (and to a lesser extent Chinese) aid assisted revolutions and radical states, the communist ability to project military power trailed the West into the 1970s. Tricontinentalists thus relied upon flexible ad hoc alliances to advance their goals. OSPAAAL provided a clearinghouse for information, but there were no bylaws or regular summits as occurred with the NAM. Rather, the UN and NAM became forums for Tricontinental cooperation and negotiation. Aid came mostly via bilateral relationships with communist states and regional Third World allies, with many parties also making broad appeals for assistance from sympathetic Western audiences and progressive European governments.

Fifth, Tricontinentalism hinged on non-white racial identity, but in a specific way. This tendency sprang from two factors: its distinct opposition to a US-championed form of imperialism overlaid with Anglocentric race connotations and the historic attempt to bridge Marxist and nationalist visions of revolution. Unlike Bandung’s implicit racial solidarity and Non-Alignment’s conscious attempt to transcend the issue, Tricontinentalism used racialized rhetoric to mobilize support and to focus attention on deep-seated social inequalities closely associated with empire and identity. Political movements incorporated cultural renovation projects that often balanced sub-national, national, and pan-ethnic identities by selectively redeploying local traditions and regional affinities under the umbrella of anti-imperial socialist revolution.Footnote 42 Racial identification thus became a fluid, often symbolic element within Tricontinentalism. Rather than a static biological category, “color” sat at the intersection of programs meant to combat political, economic, and cultural disparities. It became shorthand for a politico-ideological affinity associated with the Global South, what Mahler describes as a “metonymic color politics.”Footnote 43 Tricontinental definitions of non-white races stretched to incorporate light-skinned elites in North Africa and Latin America, and they allowed cultivation of white Euro-Americans as anti-imperial allies and even members of nationalist movements in Mozambique and South Africa. Tensions existed because the line between race pride and race hate was fungible, but most theorists argued racism was anathema to the egalitarian Tricontinental movement. Indeed, emphasis on specific racial identities threatened to divide the diverse anti-imperial coalition if used as the sole foundation of political unity. A generalized claim to non-whiteness thus became a powerful rhetorical and symbolic representation of historic oppression as well as a rallying cry that empowered and connected movements.

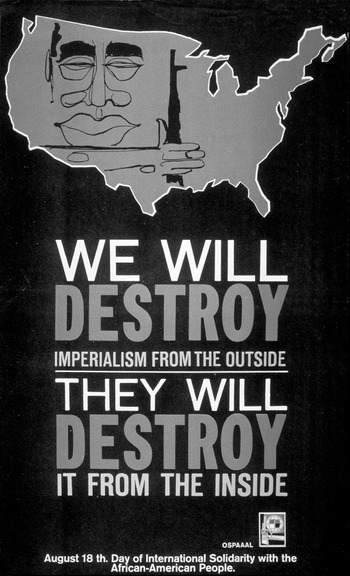

Sixth, all these elements encouraged Tricontinentalism to make greater space for nonstate movements. Nearly 40 percent of Havana conference delegations came from anti-colonial liberation parties or leftist opposition operating in independent Southern states (see Map 0.2). And Tricontinentalism arguably proved most beneficial to such groups as the African National Congress (ANC) and South Vietnam’s National Liberation Front (“Viet Cong”), which could claim legitimacy as authentic revolutions when recognized by Third World allies and operate with funds from benefactors like the Soviet Union. Treated essentially as governments-in-waiting, these groups were important components of the successful Anti-Imperial Project since they weakened imperial and collaborationist states from within (see Figure 0.1). Additionally, the ideological and racial flexibility of Tricontinentalism encouraged appeals to all “progressive” forces, which included Western domestic organizations that opposed the policies of sitting governments.Footnote 44 However, the process of identifying authentic revolutionary movements and sufficiently progressive allies in Western states was a complicated one that nominally considered ideology, identity, and geography but revolved heavily around personal connections. Publications such as OSPAAAL’s Tricontinental, conferences like the Sixth Pan-African Congress of 1974, and various diplomatic junkets sponsored by countries such as North Vietnam and Cuba identified groups and built networks between them. But membership in the Tricontinental movement was fluid and its decentralized nature militated against clear leadership, so there was not always agreement on which parties represented authentic revolutions or allies.

Map 0.2 Countries represented at the Havana conference, January 1966Governments/ruling parties: Algeria, Republic of Congo (Brazzaville), Cuba, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, United Arab Republic, Democratic Republic of Vietnam, Tanzania, Uganda. Liberation parties from colonial/dependent territories: South Africa, South-West Africa, Angola, Lesotho, Botswana, Guiana, Guinea-Bissau, Mauritius, St. Thomas and Prince Island, Mozambique, Palestine, Puerto Rico, Swaziland (Eswatini), South Yemen, Zimbabwe. Leftist opposition/liberation groups from independent Global South states: Burundi, Congo-Lusaka, Chile, Guatemala, Haiti, Laos, Lebanon, Morocco, Mexico, Niger, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Thailand, Uruguay, Venezuela, Somaliland. Solidarity parties: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Cambodia, Colombia, (North) Korea, Costa Rica, China, Cyprus. Ecuador, El Salvador Guadeloupe, (French) Guiana-Cayenne, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Jamaica, Japan, Jordan, Malaya, Martinique, Mongolia, Nepal, Nicaragua, Oman, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Dominican Republic, Rwanda, Syria, Sudan, Trinidad and Tobago, South Vietnam, USSR, Yemen.

Figure 0.1 The OSPAAAL publication Tricontinental regularly included posters highlighting specific movements and their relationship to the larger anti-imperial struggle, a practice that established both a roster and an iconography of revolutionary radicalism. This poster captures a common theme related to solidarity with the African American struggle, but it also points to the revolutionary logic uniting state and nonstate actors. OSPAAAL, artist unknown, 1967. Offset, 52x31 cm.

Nonetheless, this flexibility and transnational appeal was vital to Tricontinentalism’s popularity. Marginalized peoples in places as diverse as the United States and Palestine gained inspiration from this global challenge to the status quo, defining fictive transnational kinships within the Third World framework as a way of building domestic momentum on foreign successes.Footnote 45 OSPAAAL literature and the writings of Tricontinental personalities such as Mao, Fanon, Nkrumah, Cabral, and Guevara were pivotal in building this solidarity. New critiques of domestic systems evolved by reproducing and adapting the Marxist worldview, ideas of self-determination, and ideological solidarity central to Tricontinentalism. In Western democracies, this most often inspired “Third World” pride movements and the rise of New Left politics, though a few groups – such as the Black Panthers or the Baader–Meinhof Gang – adopted either the trappings or tactics of armed revolt.Footnote 46 Violent uprisings were more common in the West’s Southern allies, such as those waged by the PLO and Naxalite Movement in India. Since Tricontinental legitimacy came in part from the ability to wage revolution, internal competition within these movements rewarded aggressive factions with expanded membership (at least temporarily), a trend that partially explains the terrorist tactics of groups like the PLO.Footnote 47

Finally, Tricontinentalism proved attractive because it produced tangible results, if never on the scale that ardent advocates desired. The most obvious concrete benefit was material aid – educational, medical, and military. Military assistance was vital to revolutions in Africa, Asia, and Latin America because their legitimacy required them to wage armed struggles, but providing aid – in whatever form – also legitimized benefactors’ commitment to redressing global inequalities. Generally, there existed two primary avenues, either involving regional assistance or the import of arms from the communist world (especially Czechoslovakia, China, and the Soviet Union). Regarding the former, anti-imperial states such as Egypt set the standard by supplying arms to liberation movements in nearby countries in the early years of the Cold War. Later, Algeria and Cuba exported weapons and expertise to neighboring states in attempts to spread revolution across their respective continents, and the North Vietnamese provided shelter to the Khmer Rouge during its formative years.Footnote 48 Southern intercontinental exchanges were rarer for both practical and political reasons, which explains the need for alliances with the communist superpowers and states like the arms-exporting Czechoslovakia. After setbacks in the 1960s in the Congo and Cuba, the Eastern bloc increased its capacity to deliver assistance and such aid became increasingly important to revolutionary movements, especially in Africa.Footnote 49 Cuba, the Eastern bloc, and Western civil society groups also sponsored educational exchanges and provided medical assistance, enabling liberation movements to reinforce their legitimacy by providing social services during and after the revolutionary period.

Of equal if not greater importance was the political power of Tricontinentalism. Nascent revolutions and isolated states gained confidence through association with other successful movements, or what Ryan Irwin calls in Chapter 5 the power of “analogies.” External comparisons and solidarity helped revolutionaries define their movements, legitimize specific agendas, and imagine future successes that seemed unlikely in the present. Even where these connections did not produce revolution, the emergence of transnational discourses popularized once provocative ideas such as economic nationalization and legitimized liberation organizations to the point where they gained hearings at the UN and other supranational organizations.Footnote 50 These analogies also operated outside the Third World, providing avenues through which disaffected Westerners found the language of anti-imperialism necessary to challenge the Cold War excesses of their own governments. The result was the rise of the vocal political opposition in the North that sympathized or identified with the Global South, most often associated with the New Left and Black Power movements.Footnote 51 Widespread solidarity allowed for the imagining of ambitious Southern agendas while increasing the potential repercussions (international and domestic) of Western interventions in Vietnam, Angola, and elsewhere. Tricontinentalism allowed marginalized nations and parties to feel less isolated as they challenged historic Euro-American linkages and sought to remake their societies in hopeful but frequently disruptive ways.

Situating the Tricontinental Era within the Anti-Imperial Project

In recognizing the Tricontinental era as distinct from the earlier Bandung moment, it is worth considering in greater detail how Tricontinentalism fit into the longer history of anti-imperial politics in the Global South. Tricontinentalism represented a single strand of thought, but it pulled from earlier manifestations of the Anti-Imperial Project. Neither an evolutionary process nor inherently radical, this project took shape as competing visions of anti-imperialism coexisted, jockeyed for support, and borrowed from each other.Footnote 52 Shared worldviews rose to prominence when leaders in the Global South adopted similar approaches to deal with contingent but comparable problems and opportunities. Specific ideologies or strategies gained influence when structural changes to imperial practice and the international system invested Southern actors with increased cultural, economic, or political power that allowed them to pursue more ambitious programs. Yet Northern – and specifically Western – power proved robust, meaning the distance between imagined possibilities and realities has remained frustratingly persistent. The result was an alternation between pragmatic compromise and radical challenges, which gradually chipped away at Northern preponderance but rarely at the pace or to the extent desired by anti-imperialists. Tricontinentalism represented one of the radical swings of this pendulum.

Localized resistance challenged European expansion from its beginnings into the twentieth century, but pan-civilizational programs informed the first attempts to forge Southern solidarity. The most diplomatically powerful cohered around independent states such as Japan and the Ottoman Empire, which championed Pan-Asianism and Pan-Islamism, respectively. Cemil Ayden argues they offered “a corrective critique of the world order” by universalizing Western notions of civilization while celebrating non-Western traditions, undermining the racialized hierarchy that informed Euro-American claims to superiority.Footnote 53 Yet in key ways, these were reformist movements. The Pan-Asian and Pan-Islamic projects essentially claimed equal status alongside the world’s modern empires rather than seeking to upset the system itself.Footnote 54 Though more ambitious, they were comparable to the efforts of the Indian National Congress and what became the South African ANC, which redeployed imperial claims in order to increase the authority of a mostly educated, Westernized elite in colonial governance. Even Pan-Africanism bent to the limitations of the era, though its opposition to the interrelated policies of American segregation and European colonialism transcended regional borders and the need for state sponsorship to offer a radical intellectual challenge to empire. For example, most speeches and conclusions of the 1900 Pan-African Conference in London, where DuBois powerfully articulated the twentieth century’s greatest problem as that of a global “color line,” primarily demanded equality and a greater role for an educated black elite within government.Footnote 55 These pan-civilizational campaigns imagined cross-border solidarity and struck at the cultural and racial hierarchies of Northern imperialism. But their end goals involved participation in the existing system, and many successful examples deployed their own paternalistic and/or chauvinistic assumptions even as they challenged Western imperialism.

While cultural and pan-projects influenced Tricontinentalism, the worldview owed much to interwar organizing, as Anne Garland Mahler notes in Chapter 1. World War I weakened European claims to superiority and, with the October Revolution demonstrating the feasibility of revolution, initiated a radical interwar period that moved beyond calls for reform. Communism did not inspire this radical turn; indeed, myriad local frustrations and anti-colonial networks formed before World War I and fueled major revolts during the conflict.Footnote 56 But, as Robert J. C. Young notes, “[Marxist] political discourse constituted an instrument through which anti-colonial struggles could be translated from one colonial arena to another.”Footnote 57 Lenin’s formulation of empire as the highest stage of capitalism provided a global framework for understanding Western hegemony and mobilizing non-industrialized populations, ultimately legitimizing alliances with anti-colonial nationalists as first steps toward socialist revolution. Intra-imperial migration and urbanization helped spread Marxist thought, aided by the foundation of the Comintern in 1919 and attempts to integrate Asia into a global vision of revolution. The result was a flurry of organizing. The less closely policed metropolitan cities of Paris, London, Berlin, and New York became hubs linking global anti-imperial networks, joining established regional centers such as Cairo, Delhi, Shanghai, Tokyo, and Mexico City. Communist parties offered some of the strongest critiques of empire, racism, and fascism, expanding membership from Lisbon to the US South and becoming centers for nationalist revolt when colonial crackdowns weakened alternative parties.Footnote 58 Communist networks offered subject and marginalized peoples the freedom and funds to explore radical forms of resistance and exchange ideas on social reforms at home, connecting Asia, Africa, Europe, and (intermittently) Latin America behind a common worldview.

Yet like Tricontinentalism, this era’s brand of leftist anti-imperialism achieved its broadest impact by moving beyond the strict appeal of Soviet-style communism. The Comintern and Berlin-based League Against Imperialism (LAI) provide examples. Launched in 1927 with Comintern funds, the LAI became a meeting place for a variety of left-leaning dissidents, ranging from the francophone African communist Lamine Senghor to Jawaharlal Nehru.Footnote 59 The Marxist worldview provided a useful conceptualization of empire, but the racial and cultural inequities that justified colonialism and segregation led them to define Southern liberation – not a proletariat-led emancipation – as driving forces of global socialism.Footnote 60 This strained relations with Moscow, whose decision to prioritize class warfare in 1928 mixed with Comintern inflexibility to gradually alienate nationalists and anti-racist activists. But this break encouraged the redeployment of Marxist ideas in creative ways, reflecting Oleksa Drachewych and Ian McKay’s argument that the Comintern served less as “prison-house” than “seed-bed” for revolutionary ideas.Footnote 61 Always quite heterogenous, local parties and relationships created through groups like the LAI inspired a diverse, decentralized network beyond Moscow’s control. Circulation and adaptation of leftist programs encouraged anti-imperialists generally to strengthen their commitment to social justice programs and nationalists to break completely with imperial metropoles. Thus, a socialist worldview influenced Nehru’s organizing for Purna Swaraj (self-rule) and later INC foreign policy, while also helping convince exiled Algerian Messali Hadj to embrace independence from France by merging leftist anti-imperialism with an Islamist form of Arab nationalism.Footnote 62

It is important to recognize, however, that leftist anti-imperial influence was just one factor promoting this radical turn in the interwar period. Pan-projects informed some of the most popular movements of the early 1920s, notably the Indian Khilafat and Marcus Garvey’s black nationalism. The Wilsonian Moment proved fleeting, but non-leftist radicals adopted the language of nationalism to demand clean breaks from European control. Specific visions linking cultural renewal with independent nations motivated some of the most successful interwar movements. Perhaps most famously Gandhi’s vision for India set out in Hind Swaraj rejected foreign rule, Western civilization, and aspects of modernization in ways that contrasted with pre-war Pan-Asian movements and frustrated allies like Nehru. In the Middle East, suspicion of secularism meant local and Pan-Arab nationalists radicalized the anti-imperial movement in Syria and Egypt. Even the Baath Party, which cohered around Paris-trained radicals, adopted a specifically Arabic view of socialism that did not seriously incorporate Marxist elements until the Tricontinental era.

Socialist anti-imperialism clearly did not dominate every interwar movement, but it proved important for efforts to knit movements together. Alternative anti-imperial networks did exist – notably the authoritarian, anti-liberal modernism that connected Nazi Germany, India, and the Middle East – but leftist internationalism provided the most effective and widely adopted foundation for building solidarity across regions and cultures.Footnote 63 Its revolutionary worldview was universal, allowing adaptation (with or without Comintern permission) within a variety of circumstances and political formations. This latter point is especially important given Frederick Cooper’s reminder that the nation-state was not the inevitable result of decolonization.Footnote 64 Southern applications of socialism legitimized everything from progressive pan-civilizational movements to what Gary Wilder has called “postimperial and postnational federation” that ideally transcended North-South divides.Footnote 65

The combination of universality and adaptability explains why the socialist worldview became so important to interwar anti-imperialism. Adapting Marxist conceptions of empire provided activists with a consistent logic for situating local struggles within larger contexts, reimagining both national and pan-projects in more progressive ways while stitching them together across regional and identarian lines.Footnote 66 The resulting framework informed nascent Afro-Asianism and later Tricontinentalism. One can see this process in Pan-African politics of the era. Minkah Makalani argues Asian challenges to Eurocentric communism helped open the movement to black radicals such as George Padmore and Garan Kouyaté, who sought new associations after the Comintern proved an unsuitable vehicle to address the race question.Footnote 67 This coincided with the leftward drift of traditional leaders like DuBois now disillusioned with calls for gradual, elite-driven change. A powerful black radicalism formed at the intersection, integrating race consciousness into a Transatlantic movement against empire and racism that also highlighted avenues for broader collaboration. Hakim Adi notes the programmatic and personal connections linking the Pan-African and Subject People’s Conferences of 1945 illustrate how Southern socialist anti-imperialisms encouraged the emergence of Afro-Asian solidarity.Footnote 68 DuBois recognized the reality of a global color line separating North and South decades prior, but interwar leftist networks translated solidarity from the realm of thought into concrete politics.

The Bandung era built on this Afro-Asian unity, but the new possibilities offered by postcolonial diplomacy moderated the thrust of the Anti-Imperial Project. After Indian independence in 1947 launched the process of decolonization, the proliferation of dozens of new countries created an opportunity to build formal diplomatic alliances without having to operate through colonial administrative centers or European-controlled organizations like the LAI. It also compelled revolutionaries to become statesmen responsible for the management of diverse, often underdeveloped nations. The process of establishing stable governments and reinforcing sovereignty led many to temporarily moderate their internationalist ideologies. Bandung emerged in 1955 from this context, organized by moderate anglophone Asian states seeking to manage regional tensions exacerbated by the Cold War. Their goals were anti-imperial but did not envision a militant bloc. Rather, Bandung sought to encourage decolonization while subsuming ideological differences within respect for state borders and diplomatic collaboration in pursuit of common goals.Footnote 69 The Third World that the Bandung organizers envisioned was neutralist; states retained maximum flexibility to pursue national interests. As Michele Louro notes in her perceptive study of Nehru, this approach was “distinct if not anathema to interwar anti-imperialism.”Footnote 70 In some ways, it recalled late nineteenth-century attempts to claim status within the extant international system, a notion that seemed plausible given the proliferation of nation-states and their supposed equality within global institutions such as the UN.

The state-based reformism quickly proved insufficient. Postcolonial governments – moderate and radical, regionally powerful and marginalized – had varied interests and concerns. Attendees at Bandung were unable even to agree on a common definition of imperialism, though all opposed it. India was a regional power that used neutralism to its advantage, but vague promises for coordination offered little to weaker states burdened with unwanted linkages to former metropoles and minimal leverage. Western interventions still ran roughshod over economic and political sovereignty, as evidenced by the Iran coup and the Suez and Congo crises. Radical leaders such as Indonesia’s Sukarno and Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser argued aggressive action was needed to root out Northern advantages baked into the international system. This approach contrasted sharply with Nehru’s Panchsheel ideal of peaceful coexistence through mutual respect, which augured for a passive non-alignment in line with Bandung’s final communique but struggled to respond to events like Suez.Footnote 71

The radical shift led directly to Tricontinentalism. The AAPSO meetings in the 1950s reflected this inclination, incorporating nationalist organizations and flirting with expanded communist alliances. The lack of Third World consensus scuttled attempts to organize an inclusive Bandung II, but the dream of speaking with one voice continued even as ideological lines developed.Footnote 72 The formation of the NAM must be understood in this context. It was not a singular movement but a forum where diverging strands of anti-imperialism competed. Nasser hoped it would cement his leadership while Nehru wanted to restrain the radicalization of the Afro-Asian movement.Footnote 73 Yet by 1964, militancy was winning out. At that year’s NAM conference, Sukarno joined with Nasser, Kwame Nkrumah, and others to champion an active struggle against imperialism. Peaceful coexistence, Sukarno argued, would only emerge from “a balance of forces” in which “imperialist States” confronted a Third World with “equal strength we can obtain only through solidarity.”Footnote 74 These individuals gradually lost power in coming years, but there was a clear shift occurring. The first generation of statesman leaders began to give way to the militant, socialist cadre of Guevara, Castro, Fanon, Cabral, Mehdi Ben Barka, Le Duan, and Yasser Arafat well before the Havana Conference.

Extent and Limits of the Tricontinental Era

In some ways, Tricontinentalism was an attempt to revisit interwar radicalism using the power of independent nation-states. While early radicals flirted with alternative political formations – notably Nasser’s UAR and Nkrumah’s Pan-African dreams for West Africa – Tricontinental adherents pragmatically accepted the nation-state as the primary mover of international affairs. But they also understood the limits of Southern sovereignty, which made Bandung reformism insufficient. The US-supported coups in Ghana and Indonesia illustrated both the necessity of militant policies and dangers of pursuing them alone. Tricontinental solidarity promised to protect vulnerable revisionist states by imagining new challenges to Northern hegemony that used the full array of diplomatic, military, and economic resources available to postcolonial nations.Footnote 75 Armed revolutions grabbed headlines, but they were one tool in the larger anti-imperial arsenal. Specific initiatives, such as the Cuban attempt to change international law on mercenaries that Eric Covey examines in Chapter 11, were sometimes too ideologically specific to gain widespread support. But their articulation at the international level influenced the tenor of Third World politics and helped legitimize ambitious reimaginings of the international system that struggled to gain traction both before and after the Tricontinental era.

Therefore, it may be useful to consider the programs related to the New International Economic Order (NIEO) as a product of this era, if not directly of Tricontinentalism. While emphasis on UN negotiations and incrementalism implies connections to Bandung, the program’s attempts to challenge Northern hegemony by advocating global socialism reflected Tricontinental priorities and offered a revolutionary challenge to the international order.Footnote 76 That advocates believed such a project was possible owed much to the politics of the time. The radical shift in the Third World inspired ambitious agendas while the proliferation of armed revolts made confrontational diplomacy seem tame by comparison. Tricontinental advocates and sympathizers – notably Algeria – acted as catalysts for the NIEO in Southern dominated forums like the 1964 UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) that launched the G-77. At the same time, revolutionary states such as Iraq and Libya guided OPEC toward more aggressive negotiations, galvanizing calls for resource sovereignty at the center of the NIEO model. While Jeffrey James Byrne argues in Chapter 6 that the Algerian drift from Cuba signaled the decline of Tricontinentalism, it may be more accurate to describe a divergence of tactics, at least at first. Algeria continued to support armed revolutions for anti-colonial African groups (and famously sheltered Black Panthers into the 1970s) but increasingly emphasized the pursuit of radical programs via diplomatic and economic means. Yet the intellectual connection between these two strategies remained. Head of state Houari Boumédiène conceptualized the nation’s international development strategy as “an extension of the struggle for national liberation” and implied that assertive economic proposals were preferrable alternatives to violent means of undoing structural inequalities.Footnote 77

The relationship between these economic proposals, Tricontinental momentum, and the threat of militancy partially explains why such initiatives gained broad support. Revolutionary states embraced policies such as resource nationalization, and the popularity of radical leftist ideologies during this period encouraged moderate states to follow suit. As Giuliano Garavini notes in his detailed study of OPEC, the Venezuelan government adopted radical economic policies in response to similar moves by Latin American socialist states such as Chile and pressure from “left-wing opposition that engaged in guerrilla tactics and widespread social unrest [fueled by students and workers].”Footnote 78 Many Southern governments adopted policies once deemed overly provocative or even impossible in part to undermine the political attraction of leftism or revolution. And similar considerations may help explain why a surprising number of Westerners believed these ambitious economic programs might succeed and a handful of mainly European politicians entertained negotiations, a reality Nils Gilman finds even more remarkable than the NIEO itself.Footnote 79 Figures like Willy Brandt believed that only by addressing the global economic divide could world leaders mitigate the brewing revolts that threatened to engulf both North and South, many of which reflected Tricontinental motivations.Footnote 80 By approaching Third World organizations from the NAM to UNCTAD as forums where anti-imperial ideas were debated and often produced compromise policies, we can see the gravitational effects of Tricontinentalism during this era. Relatively few Southern states officially adopted the full breadth of the militant worldview, but the appeal of radical anti-imperialism encouraged postcolonial leaders to imagine ambitious challenges to the international system and compelled reluctant governments to go along for the ride.

Tricontinentalism, though, had limitations. With few formal institutions, solidarity depended on flexible ad hoc alliances between states and transnational groups whose bold ambitions wrestled with insecurity, economic disadvantages, and the need for prudence. The broad coalitions required to mitigate these weaknesses always faced the threat of free-riding and defections as states constantly reassessed their best interests. Moreover, calls for revolution competed with moderate visions of South-South cooperation championed by states ranging from China-wary India and Africa’s Monrovia Group to US clients such as Iran and South Vietnam, which remained dependent on Western aid even as they explored new coalitions to promote beneficial trade relations and development programs. Dominant within Third World circles beginning in the 1960s, arguably climaxing with the victory of North Vietnam and leftist African revolutions in the 1970s, Tricontinentalism had lost momentum by the time Cuba gained the chairmanship of the NAM in 1979. China and major oil producers gained sufficient power to pursue their national interests without the need for Third World solidarity. Less fortunate states hit hard by the economic downturn of the 1970s drifted from domestic socialism and internationalist goals as they sought austere loans from Western governments and institutions.

Tricontinentalism also suffered from internal weaknesses. Anti-imperial solidarity helped provide states such as Cuba and Vietnam with a national purpose – a unifying myth or what Partha Chatterjee identifies as a sense of community – that united diverse classes, ethnicities, and constituencies within locally constituted but globally relevant struggles.Footnote 81 It provided a defense not just against foreign threats but against anti-revolutionary factions at home.Footnote 82 Yet this practice had downsides, especially after transitioning to the postcolonial state. Leaders used revolutionary goals and militant mindsets to justify anti-democratic practices, economic disruption, centralization of power, and the crushing of dissent. The ability to contextualize internal challenges internationally allowed officials to summarily dismiss criticism, downplaying setbacks as by-products of foreign meddling or justifying domestic suffering as necessary to achieve bigger objectives. Allied governments expressed objections quietly, hesitant to critique partners in struggle. Western policies that isolated and attacked leftist states – especially in the 1980s – reinforced these tendencies, discouraging the transition from revolutionary conflict to revolutionary development. Tricontinentalism thus became a double-edged sword, legitimizing nationalist revolts but potentially weakening accountability after victory. This dissonance between stated ambitions and realities ultimately blunted revolutionary zeal. As a result, state proponents of Tricontinentalism dwindled, even as its radical vision of anti-imperialism took root in academic discourses and continues to inform contemporary movements.

What then replaced Tricontinentalism at the forefront of the Anti-Imperial Project? In Chapter 3, Paul Thomas Chamberlin considers one possibility by looking at the changing politics of the Middle East. The more controversial elements of Tricontinentalism – its ideological litmus tests and flirtation with anti-Western identarian politics – provided fertile ground for the rise of Hamas and the Ayatollah Khomeini. Their sectarian platforms called into question the efficacy and legitimacy of secular leftist groups like the PLO while drawing on historic elements of the Anti-imperial Project. Khomeini defined a fundamentalist Islamist revolution as the only way to purify Iran of the damaging modern “isms” proffered by both the United States and Soviet Union. Situating Iran within the broader struggle waged by many non-Muslim states of the Third World, he argued “Islam … is the supporter of all oppressed people of the world.”Footnote 83 While Khomeini and others adapted rhetoric, tropes, and tactics from Tricontinentalism, they definitively broke with the secular worldview and communist-aligned socialism to champion a network of Islamist radicals that eventually spread beyond the Middle East to Asia and Africa.Footnote 84

Byrne offers another possibility in Chapter 6 with his reference to the rise of anti-imperial “negotiators armed with briefcases and professional degrees.” Revolutionary states increasingly emphasized the use of diplomatic and economic suasion to change the balance of relationships with the Global North. Yet when certain resources and markets proved more vital than others, many countries quietly abandoned grand Third World projects in favor of individual development. China and oil-rich states found success combining private enterprise with the centralized, targeted investment, many emerging as regional powers. Prashad has called this trend “neoliberalism with southern characteristics,” but in so characterizing it he downplays the long history of Southerners redeploying Northern ideas to challenge global inequities.Footnote 85 While self-serving, states such as China, Brazil, and even Nigeria position themselves as alternatives to traditional Euro-American dominance trying to bend the existing system to the advantage of historically exploited states. Admittedly, they have done so without grand, egalitarian projects like the NIEO, opting instead to claim the roles of economic drivers and models for Southern development exemplified by the BRIC(S) group (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). Joint projects like the New Development Bank hint at potential alternatives to Western institutions but still generally operate within the extant system. This – along with accusations of paternalism and imperialism leveled at China by countries like Zambia – recalls earlier reformist anti-imperialisms, though recent Chinese flirtations with an autocratic anti-US alliance hint that more assertive challenges may be coming. These examples show that the Anti-Imperial Project has consistently sought to reshape the world infrastructure, but the “radical potential” – as one group of scholars laments – has varied depending on the dominant trends motivating politics in the Global South at any given moment.Footnote 86

The broad overview elicits a few final reflections on the Anti-Imperial Project and Tricontinentalism’s place within it. First, though it is impossible to talk of a singular anti-imperial movement, consistent elements informed various intersecting ideas that collectively tried to erase the gap between North and South. These include the celebration of Southern cultures as equal or superior to Western civilization, the search for sovereignty, greater global economic equality, and the belief that some level of transnational coordination was needed to combat global Euro-American imperialism. Second, certain approaches became prominent during specific eras in ways that tended to produce a kind of gravity, which influenced the forms and ambitions of various initiatives. The outline above hints at a cyclical toggling between moderation and radicalism. Groups and states sought to use access to new forms of power – education, political sovereignty, or economic resources – to reform the system, only for marginalized groups to adopt radical solutions as North-South inequalities proved stubbornly persistent. Radical turns helped wrest concessions from the North, starting the cycle again. Third, pan-projects gave way to increasingly inclusive visions of Southern solidarity that sought an independent path separate from but informed by the modernizing ideologies of the Cold War. The creation of institutions such as the NAM and the G-77 represented the pinnacle of this unifying impulse, but the nature of the Anti-Imperial Project made speaking with a single voice difficult. The Bandung vision could not deliver effective unanimity, but the ideological cohesion envisioned by Tricontinentalism struggled to obtain and sustain wide support. The elusive dream of uniting behind a singular movement succumbed to the sheer diversity of the Global South and what Sukarno called “an age of division and diverging trends.”Footnote 87

Finally, my attempt to define Tricontinentalism’s place within the long durée of anti-imperialism tentatively offers a historical vocabulary to discuss Southern politics. The major ideological alternatives described in this section were unique, competing iterations that collectively constituted the Anti-Imperial Project, which spanned the last century and continues to inform contemporary debates. The term Third World or Third World Project is one part of this longer history, collectively describing the countries and ideologies that tried to use the specific power dynamics of the Cold War to advance calls for self-determination and sovereignty within the Global South. This did not preclude collaboration with one or other bloc but positioned the goals of Southern anti-imperialism as distinct from both Western and Eastern uses of the term. While scholars have proposed the Global South as describing a specific set of politics, a somewhat constrained definition may be useful within historical circles.Footnote 88 I and many authors in this volume use it as geopolitical shorthand for Asia, Africa, and Latin America with attention to their diasporic extensions, which shared historic experiences of colonialism and empire, social marginalization, economic disparity, and resistance. The Global North constitutes the wealthier, industrial regions concentrated in Europe and North America that championed various universal modernizing ideologies with imperial and/or hegemonic overtones. As in the South, these ideas competed, especially during the Cold War’s East-West conflict. This geopolitical use captures the common experiences that promoted collaboration across continents and also recognizes the spectrum of ideologies present in both North and South. While far from definitive, this terminology provides some clarity in discussing broad anti-imperial impulses and their relationship to specific historical worldviews, strategies, and programs.

The Tricontinental Revolution explores elements of the ideas above by examining the international affairs of a wide variety of actors. Part I, “Chronologies of Third Worldism” frames the origins, rise, and challenges of Tricontinentalism with a trio of chapters. They situate the Havana conference as a revisitation of interwar solidarities that responded to key events of the 1950s and 1960s, but which ultimately faced powerful alternatives to secular revolution. Part II, “A Global Worldview,” explores Tricontinentalism beyond Latin America with attention to North Vietnam, South Africa, and Algeria. These chapters investigate how individual revolutions conceptualized international affairs, as well as the benefits and limitations of radical solidarity politics. Part III, “Superpower Responses to Tricontinentalism,” delves deeper into the ways the superpowers received attempts to organize a radical Third World, detailing both Western hostility to the project and the constraints placed upon it by the Sino-Soviet conflict. Part IV, “Frustrated Visions,” considers the ambitious visions for the international system held by Tricontinental advocates, ranging from Amílcar Cabral’s attempts to bridge the North-South divide to a rethinking of the role of mercenaries in international law. Disappointments emerged not just from the hostile reaction of superpowers but also from the inconsistencies and tensions that existed within the social and political programs of Tricontinentalism.