The significance of what would come to be known as the “Third World” was not obvious at first for communists. In the initial years after the Bolshevik revolution, the international attentions of men such as Lenin, Trotsky, and Zinoviev were squarely focused on revolution in Europe, particularly Germany, as both the logical site of socialist revolution and the political and economic prerequisite for the viability of their own project. It was only after their failure to bring revolution to the heart of Europe that they began to turn their attentions elsewhere, especially to Asia, with the hope of undermining the capitalist-imperialist system in its soft, colonial underbelly.Footnote 1 At first then, the significance of the developing world was secondary: it was a means of weakening the capitalist system in its North Atlantic heartland in order to inspire revolutionary upheavals there. The later Cold War as we know it, which became hot almost exclusively in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, therefore requires some explanation. Why were so many resources devoted to establishing and maintaining friendly and/or Marxist-Leninist regimes in these places? Why did acquiring the support of the developing world become so important to the Soviets, Chinese, and others?

The problem was that, in the aftermath of World War II, the capitalist countries failed to return to depression and, as they built new social welfare systems, the opportunities for revolutionary upheaval seemed to diminish. Instead, revolutionary energies exploded across the colonial and postcolonial world. The Soviets therefore had to find a way to lead a different revolution than the one they had anticipated. However, there were many political leaders and movements in Asia, Africa, and Latin America that espoused their own revolutionary ideologies, some claiming the terminology of socialism, a few of whom – figures like Nehru, Nasser, Sukarno, and Nkrumah – cast a wide shadow on the global stage. Others even sought to claim the mantle of communism, including Tito in Yugoslavia, some of the leaders of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam at times, and Fidel Castro of Cuba. The most dangerous threat to the Soviet claim to leadership of the world revolutionary process was the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Each of these actors had its own agenda and rivalries, and the struggle for the political leadership of the developing world became a tangle of alliance politics, ideological compromises, and revolutionary agendas.

At first, the Soviets saw the new PRC as an asset in their attempt to play this role of leader of the “world revolution.” Moscow envisioned a division of labor in which Beijing would act as a sort of subcontractor responsible for revolution in Asia, while it continued to focus on the West. Though the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was excluded from the 1947 founding conference of the new Communist Information Bureau, or Cominform, which was limited exclusively to European parties, Mao broached the idea of China leading an “Asian Cominform” even before the proclamation of the PRC, which received a positive response from the Soviets.Footnote 2 Though the Asian Cominform idea never formally came to fruition, in practice China’s leadership of the Asian revolution was forged in war – in Korea against the US-led UN forces and in Indochina against the French. The militant role fulfilled by the Chinese allowed for not only a geographic division of labor but a thematic one as well, as Soviet diplomacy pushed its “peace offensive” in postwar Europe, symbolized by the founding of the World Peace Council in Paris in 1949. Even during this arrangement, however, Chinese leaders saw it as more than just a convenient division of labor. As CCP theorist Lu Dingyi wrote in 1951, while the Russian October Revolution was a “classic example of revolution in the imperialist countries,” the Chinese Revolution would be the model for the “colonial and semi-colonial countries.”Footnote 3 Given that the sphere of “colonial and semi-colonial countries” was much larger than that of “imperialist countries,” it would seem that eventually the importance of the example of the Chinese Revolution would eclipse that of the Soviet Union itself.

This arrangement between Moscow and Beijing would, however, be torn asunder by the different uses to which each hoped to put the developing world. The Soviets were chiefly concerned with demonstrating the superiority of socialism. Moscow never adopted a view that divided the world into three parts, or three “worlds,” as many in the West and China did. Rather it saw the capitalist/imperialist system as being opposed by a unity of three forces: the working-class movement in the capitalist countries, the “national liberation movement” in the developing world, and the “socialist camp,” which it led. Within a global framework of “Peaceful Coexistence,” namely the avoidance of war between capitalist and communist countries, the victory of global socialism would be achieved through economic competition, and the Soviets therefore invested heavily in promoting socialism as a model of postcolonial development.

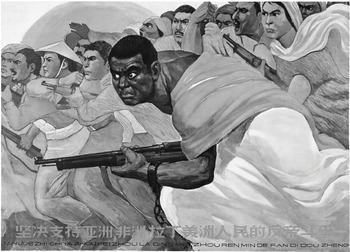

The Chinese leadership was far more skeptical of the possibility of building socialism in underdeveloped countries, comparing the situation in Africa in the early 1960s to that in China in the first decades of the twentieth century.Footnote 4 Instead, its primary goal was to create a broad, militant anti-imperialist front out of Asia, Africa, and Latin America (Figure 7.1). With American forces engaged in Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam, the PRC felt itself to be under more direct military threat from the United States than the Soviets did, and without the same sort of nuclear deterrent to protect it. For Beijing then, creating such an anti-imperialist front was less about the ultimate victory of the socialist model than it was about survival, which meant the defeat of the imperialist system that threatened it.

Figure 7.1 “Resolutely support the anti-imperialist struggle of the Asian, African and Latin American people,” declares this poster. China produced imagery in line with the Tricontinental iconography created by OSPAAAL and associated movements, but it hewed more closely to the socialist realism adapted from the Soviet Union. Shanghai People’s Fine Art Publishing House, Zhou Ruizhuang, 1967. Offset, 77x106 cm.

The problem for Beijing was that it was not just the Soviets who wanted to avoid war in the developing world. Surrounded by American forces and excluded from the international power structure – particularly the United Nations – the PRC vision of the political role of the developing world was necessarily more militant and Manichean than that of many others. In particular, Nehru and Tito sought to create their own blocs built around the concepts of “neutrality,” “positive” or otherwise, and non-alignment. For the PRC, their efforts threatened to defuse the militancy of the developing world and leave Beijing isolated in its fight against US-led imperialism. Initially, especially given the legacy of the Cominform’s battle against Titoist revisionism, Chinese leaders saw the Soviets as an ally against “neutralism,” but as the Khrushchev-led Kremlin promoted “Peaceful Coexistence” ever more strongly, they began to see Moscow as part of the problem, not the solution.

The result was an open battle between Moscow and Beijing for dominance in the Afro-Asian, and eventually Latin American, spheres, where the stakes were prestige, legitimacy, and perhaps geopolitical viability. This battle took place particularly within the Afro-Asian People’s Solidarity Organization (AAPSO), which the Chinese sought to use as their own bailiwick against the Soviet-dominated World Peace Council (WPC) and the Tito, Nehru, and Nasser-led Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). The competition culminated in the struggle over the Second Afro-Asian Conference, the sequel to Bandung to be held in Algiers in June 1965, which Beijing ultimately lost, though the conference itself was never held. The Tricontinental Conference of 1966 thus came at a time when Chinese fortunes were on the wane, but Soviet leadership of the Afro-Asian movement had been severely shaken. Both sides tried to determine the course of the conference in alignment with like-minded states. At the same time, the Cuban hosts sought to use the conference to rescue the project of Afro-Asian-Latin American solidarity from great power dominance and the Sino-Soviet rivalry that wrecked the AAPSO. The conference came near the peak of the Cuban attempt to make itself independent of Moscow and Beijing, a strategy which proved short-lived and of limited effectiveness. The impact of the conference and the resulting organization – the Organization of Solidarity with the Peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America (OSPAAAL) – proved smaller than the Cubans had hoped, in part because neither ultimately served the interests of Moscow or Beijing, who maintained their positions as the single most important patrons of Third World revolutionaries. In the end, the Tricontinental and its vision of global anti-imperial revolution turned out to be yet another casualty of the rivalries between multiple states to make the project of “Third World solidarity” serve their own needs.

Sino-Soviet Competition and the Afro-Asian Movement

Before proceeding with the evolution of the AAPSO and the Afro-Asian movement, it is worth explaining how organizations like the AAPSO or WPC operated in practice. Both were officially “nongovernmental” organizations, which meant that their members were committees set up in various states, rather than the state governments themselves. In practice, the positions of not only the Soviet Afro-Asian Solidarity Committee or the Chinese Peace Committee, but also the committees of other countries such as India or Indonesia, were worked out with the relevant government and/or party institutions in those states, often requiring discussions at the highest level. While the conferences held by these organizations were their highest profile events, in reality most of the important work occurred behind the scenes and between conferences. This work often included the distribution of funds or other kinds of aid to various organizations, releasing statements on world events, and planning for future conferences, all of which entailed political jockeying among member committees. These committees would be represented by top officials in the organization’s secretariat, such as the AAPSO’s in Cairo, and as such the makeup of the Executive Committee for each organization was of paramount importance and was the subject of much maneuvering. In advance of a conference, the Executive Committee would organize a Preparatory Committee, whose duties normally involved setting the agenda, deciding whom to invite, and writing drafts of the resolutions that the conference was to adopt. In practice, the conferences themselves were usually highly choreographed, and the fiercest political battles had already taken place before the conference started, behind closed doors among the members of the Preparatory Committee. This structure gave the Soviets and Chinese outsized influence. Both were nearly assured to be on the executive committees of any such organizations, and they had the resources and leverage to muster allies to support their draft agendas and resolutions. Consequently, such conferences were often the product of an earlier struggle between Soviet and Chinese lines, and the results enabled a type of score keeping in terms of influence between the two.

The degeneration of the AAPSO conferences in particular into fora for Sino-Soviet battles only happened, however, once the stakes and divisions had become clear. As the Afro-Asian movement began to take shape in the mid-1950s, Moscow and Beijing approached it in a similar manner. They saw it as an opportunity both to separate the newly independent states from their former colonial masters and to create positive relations with countries whose leaders were being pressured by the West to avoid ties with the communist world. At this early stage, namely that of the Bandung Conference of 1955 and the New Delhi conference of Asian Nations held just a few weeks before, neither the USSR nor the PRC was ambitious enough to seek to turn the countries of Asia and Africa into full-fledged allies of the “socialist camp.” Accordingly, Bandung was the scene of a masterful performance by Chinese Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai, whose conciliatory speech helped the PRC return to the world of Asian diplomacy, precisely what Nehru had intended by pushing for the PRC’s invitation.Footnote 5 Though the New Delhi conference, as an officially nongovernmental event, would have a lower profile, it would ultimately have the greater institutional impact, since it would call for the creation of “Solidarity Committees” in each of the participating countries, which would eventually come to form the Afro-Asian People’s Solidarity Organization.

The first AAPSO conference, held in Cairo in December 1957, was dominated by the Egyptians, riding high off Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez Canal and the subsequent events of 1956, and its militancy took both the Soviets and Chinese by surprise. The Soviets had gone seeking to focus on the “peace” struggle and economic aid, and Beijing had instructed its delegates to adhere closely to the Soviet line.Footnote 6 The militant tone of the conference, which reflected the rising wave of Arab nationalism, surprised and concerned the Soviets who worried that it would undermine their efforts to present the Afro-Asian countries as natural allies of the peace movement in Europe.Footnote 7 For the Chinese, meanwhile, the conference opened their eyes to the potential for a more militant orientation of the Afro-Asian movement than that of Bandung, one which dovetailed well with the radical turn in Chinese foreign and domestic policy that accompanied the launch of the Great Leap Forward in 1958. While the final conference resolution was significantly watered down from the opening statement, Liu Ningyi, the head of the Chinese delegation at the conference, took this to be a reflection of the fears the bourgeois-dominated governments of the newly independent states had regarding the militant feelings of their peoples.Footnote 8 In the Chinese view, opportunities for a more radical orientation of the Afro-Asian movement existed, and the obstacle was the conservatism of the new governments. In short, what the Soviets saw as a latent danger in the conference, the Chinese saw as an opportunity.

By the time of the second AAPSO conference in Conakry, Guinea, in April 1960, Sino-Soviet relations had deteriorated significantly, and the radical mood of the delegates had increased with the progress of African decolonization and the Algerian war for independence.Footnote 9 In spite of this, the Soviet delegation was determined to win adherence to its policy of “Peaceful Coexistence,” especially by promoting the idea that disarmament would liberate resources that could be employed for the economic development of the newly independent states. Meanwhile, the Chinese were worried about what they saw as the Indo-Egyptian hijacking of the conference in the name of “neutrality.” In the words of the Chinese representative at the AAPSO secretariat in Cairo, Zhu Ziqi, the Indians and Egyptians were “conspir[ing] to boost the policy of so-called opposition to blocs and nonalignment … in order to weaken and shift anti-imperialism … in order to change the general character of the solidarity movement, replace it with reactionary content and have it led by the right wing of the bourgeoisie.”Footnote 10 In the event, the rising tide of militant anti-imperialism among the African delegates carried the day, and the Chinese delegation left elated. The Indians and Egyptians, key players in the emerging non-aligned movement that would hold its first conference the following year, appraised the atmosphere of the conference and dropped their talk of “neutrality” following their opening statements.Footnote 11 At the same time, the Chinese understood that behind the efforts of the Indians and Egyptians stood the Soviet delegation, which tried to tack on a two-page addition to the General Secretary’s speech with a list of pet Soviet issues, including peaceful coexistence and disarmament.Footnote 12 The dynamics at the AAPSO increasingly seemed to pit the USSR, allied with India and Egypt, in a sort of “peace” camp against the PRC, with many allied African delegations led by the Algerians, in the “militant struggle” camp.

Over the course of 1961 and 1962, the Sino-Soviet struggle began to dominate meetings of the AAPSO and WPC, including an Executive Committee meeting in Gaza in December 1961 and a meeting of the WPC in Stockholm two months later. It was at the Gaza meeting that the first serious steps were taken to organize a tricontinental conference, an idea that had been floated by the Cubans as early as January 1960.Footnote 13 The proposal quickly became a political battleground. The Soviets sought to hold the conference under the auspices of the WPC, where they and their European allies could control the agenda, while many African delegations argued that the WPC was “not an anticolonial, anti-imperialist organization.”Footnote 14 The Chinese made the same argument at the subsequent Stockholm WPC conference, though the Soviet position won the day there with the backing of the Europeans and Latin Americans. Far from a conclusive victory, however, this served merely to clarify positions and delineate turf, and the question of under whose auspices the Tricontinental would be held was far from decided.

The calling of a tricontinental meeting would take center stage at the next AAPSO conference, held in Moshi, Tanganyika, in February 1963. By this time the Sino-Soviet rivalry so overwhelmed the organization that Tanganyikan President Julius Nyerere felt it necessary to open the conference with an admonition to the Soviets and Chinese to keep their disputes to themselves.Footnote 15 The Soviets and Chinese both spent a lot of time feeling out and cajoling other delegations in advance of the conference in order to line up support, and the Chinese arrived feeling that they had Africa “in their pocket.”Footnote 16 In a preconference meeting the Chinese taunted their Soviet colleagues, asking them “Why did you come? There is nothing for you to do here.”Footnote 17 Anticipating the struggle over the Tricontinental at the conference, the Cuban ambassador to Mali Jose Carillo, who would be representing Cuba at the conference, met with Chinese officials to gauge their support for holding the conference in Cuba, and got a positive response.Footnote 18 Two weeks later, the Cuban ambassador in Cairo met with Yang Shuo, the new Chinese representative to the AAPSO Secretariat, reiterating Castro’s eagerness to hold the Tricontinental in Havana as early as January 1964 in order to promote armed struggle in Latin America, particularly in Peru and Guatemala.Footnote 19 The Moshi conference came at a crucial juncture in the socialist camp when Soviet-Cuban relations were at their post-Missile Crisis nadir and the Chinese were trying to capitalize, as will be discussed in greater detail later. The Soviets therefore were afraid of a conference hosted by Cuba and tried to pressure the Cuban delegate not to propose Havana as the host city. Instead, they wanted the conference held under the auspices of the WPC in Brazil. The leftist government of João Goulart opposed armed struggle as the path to power, making Brazil a more acceptable location for the Soviets and the other Latin American observer delegations.Footnote 20 The Soviet effort failed, and a resolution was adopted to hold the conference in Havana. As the Chinese report described it, “The Soviet Union and its partners were completely on the defensive and isolated, in the end they slipped away in the middle of the night, heads bowed and discouraged.”Footnote 21 However, the Chinese knew that the battle was far from over and told the Cubans that it would take a lot of work to get the resolution enacted.Footnote 22

This work would be complicated by the fact that conferences and organizations attempting to speak for the developing world were now proliferating along with the increase in aspirants to leadership. While the Cubans, with help from the Chinese, were trying to organize a tricontinental meeting, Beijing’s attentions increasingly focused on a second Bandung conference, while others were determined to hold a second non-aligned conference. The politics of these three conferences – who would be invited, where they would be held, what the agendas would be, and which would come first – became entangled with all sorts of rivalries. China and India were now bitter enemies following their wars over Himalayan borderlands. India and Pakistan were fighting over Kashmir. Egypt and Indonesia were rivals for the leadership of the Islamic world. Increasingly, India and Egypt worked with the USSR to oppose China, Indonesia, and Pakistan. The former promoted the WPC and Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) along with peace and disarmament (except on the issue of Israel), while the latter group focused above all on a second Bandung conference that would give rise to an Afro-Asian attempt to overturn the existing global power structure.

A preparatory conference for the second Bandung, held in Jakarta in April 1964, achieved mixed results. It did not invite the Soviet Union, a decision that was the PRC’s chief objective. However, as the Soviet embassy in New Delhi reported, the Indians managed to get the conference pushed off to 1965 so that it would be held after the second NAM conference. They also got it moved to Africa rather than holding it in Indonesia.Footnote 23 A year later, the Soviets managed to get invited to the Islamic Conference of Asia and Africa held in Bandung, despite Chinese protests that the USSR was “neither an Asian nor an African country.”Footnote 24 The conference turned into a three-way struggle for leadership of the Islamic world between Indonesia (backed by the PRC and Pakistan), Egypt (backed by the Arab countries), and sub-Saharan Africa, which was fearful of Egyptian domination. The Soviets sought to maintain a low profile and make contacts in the name of a larger objective: getting invited to the second Bandung conference.

In early 1965, the issue of a second Bandung, specifically whether the Soviets should be invited, came to symbolize the battle between Moscow and Beijing for domination of the Afro-Asian movement. The USSR and the PRC pressured, cajoled, and bribed countries in order to get them to either support or oppose inviting the Soviets. In one instance, Zhou Enlai told Nasser to reject much needed grain from the USSR because one must “maintain principled struggle until the end.”Footnote 25 Despite Chinese pressure, momentum was building in favor of inviting the Soviets, and by the beginning of June, Foreign Minister Gromyko reported to Politburo member Mikhail Suslov that of roughly 50 possible participants, 24 to 26 were thus far prepared to support Soviet participation.Footnote 26 A final decision on whether or not to invite the Soviets was not expected until a preparatory meeting of foreign ministers on the eve of the conference. The conference was to be held in Algiers at the end of the month, but it was postponed because of the coup that overthrew Algerian President Ahmed Ben Bella on June 19, 1965. Jockeying continued in the aftermath of the coup, as the PRC embraced the new government, led by Colonel Houari Boumédiène, in the hopes of convening a conference in the fall. Once it became clear that the USSR would be invited, the PRC backed out and the conference was never held, a major defeat for Beijing in its effort to establish itself as the leader of the Afro-Asian movement.

Nevertheless, the documents available in the Russian archives about this phantom conference are instructive with regard to the Soviet approach to such conferences and the Afro-Asian world at the time. A Central Committee resolution from June 1965 directed forty-three Soviet ambassadors to meet with their host governments on the question of the Second Afro-Asian Conference and laid out the Soviet agenda.Footnote 27 Disarmament and “peaceful coexistence” were now demoted to third and fourth place behind the “activization” of American aggression in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, specifically in the Dominican Republic, Congo, Cuba, and Indochina, and the battle against colonialism and neocolonialism.Footnote 28 In a directive to the Soviet delegation in case of participation in the conference sent from Gromyko to Suslov, the emphasis was placed on highlighting the Soviet role in Vietnam and putting the Soviets at the center of efforts to form an international anti-imperialist front in favor of North Vietnam and the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (NLF), including China.Footnote 29 They were to vehemently deny any charge coming from the Chinese that the Soviets were pushing negotiations in Vietnam. In addition, the Soviet delegation was to play up Soviet anti-colonialism, especially in southern Africa. At the same time, the Soviets were to avoid any confrontation or condemnation of the PRC, for example if India tried to introduce a resolution condemning the Chinese nuclear test, despite Soviet promotion of the Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty. According to the directive, “polemics and fights with the Chinese delegations at the conference would not be in our interests, and so it would be desirable to avoid them.” Rather, if they could not get China to agree on a “union of anti-imperialist forces, it is necessary that the participants in the conference see that not we, but rather the Chinese are the instigators of polemics and division, and that we strive for constructive solutions to the tasks facing the conference.”Footnote 30 By 1965 then, the Soviet approach to establishing Moscow’s leadership of the Afro-Asian movement was to embrace anti-colonial struggle, portray the Soviet Union as the patron of fighting oppression, and act above the fray of Sino-Soviet polemics.

Though the Second Afro-Asian Conference never took place, much of this approach would be evident at the Tricontinental only a few months later. For the Chinese, the Tricontinental would come as their one last, desperate chance. The second Bandung had been a failure, and with the events of October 1965 removing Beijing’s most crucial ally in Indonesia, the Tricontinental offered one more opportunity to establish the PRC as the true leader of the anti-imperialist struggle of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, although this time it would take place under the auspices of the Cubans, who were keen to take up the mantle of leadership themselves.

The Cuban Role

The decision to hold the Tricontinental Conference in Havana, made at the third AAPSO conference in Moshi a few months after the Cuban Missile Crisis, came at precisely the moment when Soviet-Cuban relations were at their most tense and Sino-Cuban relations were at their closest. At the time, this made the decision to hold the conference in Cuba a seeming victory for Beijing, one that Moscow rued. However, this constellation of relations would turn out to be very short-lived, and by the time the conference was held, Cuba was attempting to chart its own course as the leader of an anti-imperialist front in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Cuban relations with both Beijing and Moscow were tense and, given the way that the Sino-Soviet dispute had torpedoed both the AAPSO and the second Bandung conference, Cuba was not alone in thinking that the success of Asia, Africa, and Latin America as a political force depended upon its independence from the USSR and PRC.

Soviet-Cuban relations got off to a more promising start than Havana’s relations with Beijing, despite the fact that Fidel Castro’s Cuban revolution had taken the path of armed struggle advocated by the PRC. This was in part because Castro’s group had taken power without the cooperation of the communists in Havana, so his ideological allegiances seemed uncertain, and the early evidence was concerning from China’s perspective. In January 1960, a Cuban delegation visited Yugoslavia – a country Beijing perceived as the fount of revisionism – and the two countries found a lot of common ground. They agreed on “active peaceful coexistence,” the role of small states working together on the world stage, the need for economic cooperation, and the importance of the United Nations, from which the PRC was excluded.Footnote 31 Cuba and Yugoslavia talked about holding a conference for Asia, Africa, and Latin America to address economic cooperation, which the Chinese worried was just a gateway for Tito to bring the Cubans on board with a project to launch a “third force,” specifically a political alternative to the capitalist and communist blocs. The PRC embassy in Cairo, where the Cuban delegation went before Belgrade, worried that the conference proposal was an attempt by the Cuban “bourgeois nationalists” (资产阶级民族主义者) to unite with other bourgeois nationalists throughout Asia, Africa, and Latin America – in particular Nehru and Nasser – to create a “neutralist bloc” (中立主义集团).Footnote 32 Even Che Guevara was described by the Chinese as having only “advanced bourgeois democratic revolutionary thought” with some Marxist-Leninist influence.Footnote 33

Moscow was much more sanguine in its evaluations of the Cuban revolution, and its aid relationship with Havana developed rapidly in 1960 and 1961. Politburo member Anastas Mikoyan visited Cuba in early 1960, and his positive report produced Soviet economic and military support. While Che Guevara’s visit to Beijing in late 1960 convinced the Chinese that perhaps the Cubans were more revolutionary than previously thought, they began to worry that the extent of Soviet aid to Cuba would keep Cuba from publicly supporting Beijing on the issue of peaceful coexistence versus anti-imperialism. As Guevara told the Chinese, from his perspective “Soviet support for Cuba is a true indication of the Soviet policy of peaceful coexistence,” meaning Moscow had not abandoned the struggle.Footnote 34 The chairman of the Soviet Solidarity Committee reported, following a trip to Latin America at the end of 1961, that

In the course of this year, which has been difficult for the Cubans, they have become convinced that from the Chinese they can get only revolutionary slogans and loud yelling, but real aid from the Chinese is not visible and they couldn’t see it, because the Chinese don’t have the means and the possibilities to offer any kind of significant real aid. But our real aid there is very visible, it hits everyone in the face.Footnote 35

Soon enough this aid would come to include the stationing of nuclear missiles in Cuba, but Khrushchev’s removal of the missiles in the face of the American “quarantine” without consulting Havana deeply angered the Cuban leaders. The Cuban leadership saw this as both a betrayal and evidence of cowardice on Moscow’s part, and Guevara claimed that had the missiles been under Cuban rather than Soviet control, they would have been fired.Footnote 36 Mikoyan returned to Havana in November 1962, but this time to a cold reception: Guevara would not even greet him at the airport. When Mikoyan returned to Moscow to report on his trip, his colleagues called the Cubans “unreliable allies.”Footnote 37 While it suddenly became much more difficult to distribute Soviet propaganda in Cuba, the Chinese capitalized by claiming that the Soviets had shown their true face, and that only the PRC was really willing to fight imperialism around the world.Footnote 38 In March 1963, the PRC began publishing a Spanish language edition of Peking Review known as Pekin Informa.Footnote 39 Cuba and China, as the two most militant advocates of armed struggle against imperialism, went to Moshi in February 1963 determined to make sure that it was their line that prevailed over the “peaceful,” “neutralist” one of the Soviets and Indians. In addition to pushing for the Tricontinental in Havana, the Cubans told the Chinese that there would be a secret meeting on the side to discuss guerrilla warfare conducted by the Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola, or MPLA) and invited the Chinese ambassador to make contact with them.Footnote 40 As noted above, the Soviets, together with Latin American communists who advocated a peaceful path to socialism in their countries and feared Cuban meddling, failed in their efforts to have the Tricontinental held in Brazil instead.

However, the Sino-Cuban honeymoon was short-lived. While the Cuban government may have been more ideologically compatible with the Chinese, it was dependent on economic and military aid from the Soviet Union, which China could simply not match. Castro visited the USSR in June 1963, and his conversations there with Khrushchev did much to repair the damage done the previous October, as well as to put some distance between Castro and Beijing.Footnote 41 Following Khrushchev’s removal in October 1964, the Soviets tried to organize a new meeting of the international communist movement in order to resolve the Sino-Soviet dispute, or at least isolate the Chinese. In preparation for this effort, they helped organize a meeting of twenty-two Latin American communist parties in November 1964, which the Cubans attended, that condemned “factionalism” and called for the end of Sino-Soviet polemics.Footnote 42 This meeting clearly showed Beijing that there was no hope Cuba would take its side in the Sino-Soviet dispute. It did not mean, though, that Havana was now on board with Moscow’s agenda. The Soviets continued to support the “peaceful path” approach adopted by the Latin American communist parties that allowed it to maintain relations with sitting governments, while Cuba sought to promote armed struggle in Latin America and Africa. Moscow suggested that Cuba moderate its policies in order to establish relations with its neighbors for economic purposes, but the Cubans attacked the Soviets for insufficient militarism, especially in their support of the communist cause in Vietnam.Footnote 43 In the mid-1960s then, Cuba became a sort of wild card in the world of international communism.

On the eve of the Tricontinental Conference, Castro launched a public attack on the PRC. The previous November, Cuban Ministry of Foreign Trade officials visiting Beijing were told that the Chinese would be able to send Cuba only 135,000 tons of rice in 1966, as opposed to the 285,000 tons the Cubans had requested and the 250,000 tons they had been sent in 1965.Footnote 44 This shortfall was ostensibly because of the increased needs of North Vietnam, but it was clear that it was punishment for Castro’s turn toward Moscow, and it might be reversed if he changed course. Instead, Castro decided to publicly announce the PRC’s decision on January 2, 1966, the day before the opening of the Tricontinental. It was as good a way as any to demonstrate Cuba’s independence on the eve of its biggest moment on the international stage.

The World Comes to Havana

When the conference opened in Havana on January 3, 1966, the Soviets, Chinese, and Cubans had three very different versions of what they wanted out of it. The Soviets were essentially playing defense. As long as the conference did not turn out to be a rousing condemnation of Moscow’s policies, they would consider it a success, and the fewer institutional legacies left by the conference, the better. For the Chinese, the meeting represented a chance to achieve that which they had hoped but failed to achieve in Algiers, namely an explicit condemnation of the Soviet policy of “peaceful coexistence” in the name of armed anti-imperialist struggle, ideally with the PRC and Mao acknowledged as leaders of that struggle. For the Cubans, it was an opportunity to escape from the stale Sino-Soviet polemics, break their regional isolation, and rouse the forces of real anti-imperialist struggle around the world, which Cuba was fighting with men and arms, as opposed to the rhetoric that the PRC was supposedly fighting with. In the end, it would be the Soviets who would come closest to getting what they wanted.

Soviet behavior during the conference reflected this cautious, defensive approach. They wanted to seem welcoming of the conference and its agenda, while at the same time softening its sharper edges and not giving it too high of a public profile. Leonid Brezhnev and Aleksei Kosygin greeted the conference with a short statement on the front page of Pravda that spoke of imperialist aggression in Vietnam, South Africa, Rhodesia, the Dominican Republic, and Cuba, declaring that “The Soviet people … faithful to their internationalist duty offer and in the future will offer all types of support to the people fighting for freedom and national independence.”Footnote 45 They then went on to talk about the contribution the conference could make to the cause of economic development, ending by describing the struggle of the conference participants as one “against imperialism and colonialism, for freedom, national independence and social progress, for peace between peoples.” A longer editorial in Pravda expanded upon these themes, not only talking of an economic focus of the conference but claiming that many of the delegations represented “newly developing countries which have launched on the non-capitalist, socialist path and are realizing deep social-economic transformations.”Footnote 46 It tied the cause of economic development to that of peace:

The arms race, international tensions, the interference of imperialist powers in the internal affairs of peoples, military intervention, violations of state sovereignty, the use of tensions between peoples which remain as a consequence of imperialism – all these interfere with the unity of antiimperialist forces, divert the energy and means of young states from the most pressing and fundamental problems of their national development.Footnote 47

Repeating the call to push for peaceful coexistence and nuclear disarmament, the editorial spoke of independence struggles both armed and peaceful, and added a note of caution: “It would be naïve to think that the coincidence of interests and goals of the struggle automatically create unity.”Footnote 48

The Chinese were livid at this Soviet attempt to tilt the conference agenda toward peace and economic development. A Renmin Ribao editorial summing up the conference gloated, “On the day the conference opened, the Soviet paper Pravda … attempted to divert the attention of the conference with such stuff as ‘universal peace,’ ‘total and complete disarmament,’ and ‘peaceful coexistence,’ but the delegates saw through this.”Footnote 49 The Soviet delegate at the conference, First Secretary of the Uzbek Communist Party Sharaf Rashidov, struck a more militant tone in his speech. Despite acknowledging the necessity of peaceful coexistence between sovereign states, he declared “it is clear that there is not, nor can there be, any peaceful coexistence between the oppressed peoples and their oppressors – the colonialists and the imperialists, between the imperialist aggressors and their victims.”Footnote 50 He spoke these words two months before Brezhnev officially enshrined them at the 23rd CPSU Congress as the new Soviet approach to reconciling “peaceful coexistence” and anti-imperialist struggle.

As the conference went on, Soviet coverage of it diminished. The Pravda editorial was followed by short summary pieces that appeared daily during the first week of the conference and then nearly disappeared during the second week. The closing of the conference and the final resolutions adopted were given rather short shrift in the Soviet press, limited to short pieces in Pravda and Izvestia, and a three-page article in the CPSU theoretical journal Kommunist. The Kommunist piece returned to many of the themes of the original Pravda editorial but added a critical note about the events of the conference. It recognized that the complexity and heterogeneity of the anti-imperial movement created challenges but noted that such difficulties were exacerbated by the actions of “certain delegations” that championed a more radical agenda: “Their hysterical slogans, though devoid of real content, and obstructionist positions on a number of questions summoned the danger of a schism.”Footnote 51 This was the closest the Soviets would come to acknowledging the difficult tone of the conference, where their calls for peace were not well-received by many. The important thing for them was that it was over, and the Chinese had not won the day.

Chinese coverage of the conference was a mirror image of Soviet reporting. While Renmin Ribao began slowly, with short articles limited mainly to naming speakers, the end of the conference was greeted with long celebratory pieces in Renmin Ribao and Peking Review, as well as a lengthy spread in Shijie Zhishi, the PRC’s main foreign affairs journal at this time. In typically unsubtle terms, Peking Review triumphantly concluded,

The Khrushchev revisionists’ attempts to manipulate the conference and peddle their spurious “united action” to promote their capitulationist and divisive line were thoroughly exposed and firmly rejected. They failed, too, in their attempt to control the tricontinental and anti-imperialist solidarity organization in order to bring the national democratic movement in the three continents into the orbit of US-USSR cooperation for world domination.Footnote 52

In particular, the Peking Review pointed to the defeat of the Soviet attempt to get “peaceful coexistence” included in the text of the political resolution and the adoption of a significantly more militant tone on Vietnam than that struck by the Soviets.

Vietnam was the issue on which the Chinese thought the Soviets most vulnerable and therefore the one they sought to exploit to the hilt to rally anti-imperialist sentiment against Moscow. The Chinese delegate Wu Xueqian repeatedly assailed the Soviets for supposedly seeking to negotiate an end to the war with the United States, while a parade of Asian delegations, not necessarily reflecting the positions of their governments, supported the PRC position: North Korea, Japan, Indonesia, Cambodia, Pakistan, Thailand, and “Malaya” (Beijing, in sympathy with Sukarno’s policy, did not recognize Malaysia).Footnote 53 For the Chinese, it was not just a question of how much to support Hanoi and the NLF. It was about the opportunity that Vietnam presented to fundamentally undermine US power around the globe. As Shijie Zhishi wrote,

The victorious struggle of the Vietnamese people will also have a positive impact on the American domestic class struggle and development of its revolutionary movement. American imperialism’s aggressive war has educated the American people, has made them more conscious … Over the last year, the American people have surged on an unprecedented scale in a firm and unceasing movement against the aggressive war. This movement is closely uniting with the American black people’s struggle for liberation, becoming a mighty torrent, creating a new front … This shows that the American people are already awake as never before, are going down the path of struggle against their own country’s imperialism, the prelude [序幕] to the American people’s revolution has already begun.Footnote 54

Therefore, in the eyes of Beijing, any Soviet attempt to negotiate an end to the war – even on Hanoi’s terms – could mean only that the Soviets did not share the true objective of the struggle, namely the final destruction of American imperialism.Footnote 55

Though Beijing sought to portray the conference as a victory since the Soviets did not gain official acceptance for their doctrine of “peaceful coexistence,” it also failed to get any explicit denunciations of revisionism or acknowledgment of its revolutionary leadership. In the unequal conflict between the USSR and the PRC, a draw of this sort ultimately benefited the former more than the latter, since the Soviets had other sources of influence – the WPC, for one – while the PRC had lost yet another chance to build its own international base of support.

With the conference now behind them, the Soviets sought to distance themselves from it and bury the results. The Soviet delegation at the conference felt obliged to sign the final resolution calling for armed struggle against existing governments, but the Soviet government did not feel bound by that signature. Concerned about the Soviet signature on the conference resolution, the Chilean ambassador in Moscow asked Vice Foreign Minister Yakov Malik if it meant that “the USSR will support morally and materially the struggle in Peru, Venezuela, Colombia, Guatemala, and other countries of Latin America in accord with the results of the mentioned conference.” Malik assured him that the USSR remained committed to “peaceful coexistence” and noninterference and conveniently explained that the Tricontinental was attended by nongovernmental representatives and did not reflect the positions of the Soviet state.Footnote 56 The head of the Soviet Foreign Ministry’s Latin American division gave the ambassador an official Soviet statement to that effect, though he asked that the ambassador keep the statement private so as not to embarrass Moscow.Footnote 57

To forestall the possibility of a new Tricontinental organization in Havana becoming a longer-term thorn in their side, the Soviets had managed to achieve one important goal at the conference: they got the next Tricontinental scheduled for Cairo in 1968. Cairo was already the headquarters of the AAPSO, and it had served as the location of the most recent NAM conference in 1964, so it was a place in which the Soviets felt comfortable operating. It was also one where a new Tricontinental organization would likely be subsumed by the existing “Third World” establishment. The secretariat set up in Havana after the conference was only meant to be temporary, and the question of a permanent secretariat for the new Organization for Solidarity with the Peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America (OSPAAAL) was to be decided in Cairo.

In the aftermath of the conference, the Cubans saw the potential move to Cairo as a threat, both because it meant their losing control of the organization and the possibility of OSPAAAL being effectively dissolved into the AAPSO. Osmany Cienfuegos, the new secretary of OSPAAAL, wanted to create an executive committee that would exclude both the Soviets and Chinese, arguing that such an organization would work better without them and would then be able to remain faithful to its mission of supporting armed struggle.Footnote 58 The Cubans therefore fought successfully to keep all Tricontinental organs in Havana, assuring that a second conference would never take place. After the Six Day War, Nasser and Cairo no longer had the prestige they had enjoyed in 1966 in any case. As a result, the second conference collapsed before serious negotiations had even begun.

For the next two years, the Soviets, along with AAPSO and the WPC, would conduct a propaganda battle with the Cuban-led OSPAAAL, remembering “not to exclude the possibility that our Cuban comrades might make some sort of contact with the decisions taken in Beijing.”Footnote 59 After 1968, the Cuban rapprochement with Moscow would make the point largely moot, and OSPAAAL’s relevance diminished accordingly.

Conclusion

The Tricontinental Conference in Havana took place at what might have been the moment of peak fracture in the project of building an anti-imperialist political vehicle to unite Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Sino-Soviet cooperation in seeking to turn the AAPSO into such a vehicle had collapsed amid polemical struggles that nearly tore the organization apart, and that same rivalry prevented a follow-up conference to the original Bandung Conference of 1955 from taking place. Other rivalries for various kinds of “Third World” leadership – Arab, African, Asian, Islamic, etc. – and more standard political battles, such as that between India and Pakistan, magnified the effect of the Sino-Soviet dispute by forming shifting alliances in the hopes of shaping agendas and appropriating resources. Frustration with this state of affairs led some to seek a new beginning beyond the control of Moscow and Beijing, but the Cuban effort to do precisely that faltered on the grounds of its own precarious isolation and militant sectarianism.

Cuba would have a second opportunity to pretend to leadership of the “Third World” when it held the presidency of the Non-Aligned Movement following the 6th NAM summit in Havana in 1979. This meeting came at the peak of Soviet-Cuban cooperation in the wake of joint military efforts in Angola and Ethiopia, and for many it was the moment when the Non-Aligned Movement ceased to be truly non-aligned and became the ally of the socialist camp that the Soviets thought it should have been all along. Ironically, given Soviet and Chinese claims about the importance of their revolutionary leadership, it was the creation of Tito, Nasser, and Nehru that would have the greatest longevity and come the closest to instantiating the notion of a powerful anti-imperialist “Third World” organization.

The experience of the Tricontinental and the organization that it spawned (OSPAAAL) demonstrated how difficult it was for a “Third World”-ist movement to gain traction in a world of superpowers. Convening the conference itself was hard enough, given the wariness of the Soviets with regard to Cuba’s militant “adventurism” and the PRC’s desire to turn the Afro-Asian solidarity movement into a vehicle for its own geopolitical ambitions. Nevertheless, the conference was convened, and Castro and his government put on a good show, passing more than 100 resolutions and frightening much of the Western press in the process. But the aftermath proved that these fears were unfounded. The Soviets, having done just enough to maintain their revolutionary credibility, quickly disavowed the conference and doomed the organization by pushing for the next conference to be held in Cairo. The Chinese, who had strongly resisted the establishment of a permanent tricontinental organization, poured their efforts into the organization of the next conference of the AAPSO, to be held in Beijing in 1967. Support for Hanoi and the NLF, so prominent rhetorically at the conference, still came primarily from Moscow and Beijing. The Cuban regime did not lose its desire to fight for its version of revolution around the world, but it would come to find that it could be much more successful doing so under Moscow’s umbrella. It turned out that translating the power of “Third World” solidarity from rhetoric into action required the resources of a superpower, and those resources always came with strings attached.

For US policymakers, the Havana Tricontinental Conference of January 1966 took place at a time of both confidence and vulnerability in US relations with the Third World. In the second half of 1965, the Lyndon B. Johnson administration believed that the prevailing winds in the Third World were blowing in its favor. The collapse of the “Second Bandung” African-Asian Conference at Algiers between June and October, the military coups against Algerian leader Ahmed Ben Bella and Indonesian leader Sukarno, and the collapse of the Chinese push for leadership of the Afro-Asian movement were all seen in Washington as a validation of US foreign policy and as heavy blows to several key antagonists. These perceived victories notwithstanding, however, US policymakers remained aware of the general unpopularity in much of the Third World of Washington’s perceived support for European and white settler colonialism in Asia and Africa, of the US role in global capitalism, and of the recent US interventions (overt and covert) in Cuba, the Congo, the Dominican Republic, and above all, Vietnam.Footnote 1

Unlike the Algiers conference, which was to have been a meeting of national governments across the political spectrum and including many Commonwealth and other governments broadly sympathetic to US and Western interests, the explicitly socialist and anti-imperialist Tricontinental Conference would include no voices friendly to Washington and offered no channel through which the United States might influence the conference preparations or outcome. The Tricontinental’s institutional predecessor, the Afro-Asian People’s Solidarity Organization (AAPSO), was technically a nongovernmental organization; delegates participated on behalf of national Solidarity Committees, umbrella organizations of mostly socialist and communist groups and/or liberation movements. Some of these groups worked with the blessings of their national governments, but others stood in opposition to regimes with ties to the United States. Launched at Cairo in 1957 and sponsored by the Soviet, Chinese, and Egyptian governments, AAPSO had articulated an increasingly militant and revolutionary message at a series of conferences over the ensuing decade.Footnote 2

Figure 8.1 Tricontinental iconography highlighted imperial violence, offered satiric takes on Western icons like Uncle Sam, celebrated Global South cultures, and championed militancy. Their powerful simplicity mixed clear calls to action with historic references and inferred inequalities that continue to animate anti-imperial politics. OSPAAAL, Asela Perez 1970. Screen print, 53x33 cm.

The Tricontinental Conference aimed to extend AAPSO into the United States’ backyard through the inclusion of Latin American communist parties and guerrilla movements. The conference was to be the largest gathering of self-identified revolutionaries in world history and portended nothing but hostility to US interests. Furthermore, the conference’s host, Washington’s nemesis Fidel Castro, was the very embodiment of left-wing revolutionary defiance of the United States, having already survived almost a decade of efforts first to prevent him from taking power during his guerrilla war of 1956–58 and then to undermine, isolate, and overthrow his revolutionary government only ninety miles from US shores.Footnote 3

By defining the nature of the Tricontinental Conference agenda and invitees as they did, the organizers left few if any avenues for the United States to influence the preparations for or course of the conference through allied or sympathetic delegates. Washington’s lack of leverage stands in contrast to successive US governments’ efforts to shape the course of other Third World internationalist conferences from Bandung in 1955 through the non-aligned conferences at Belgrade in 1961 and Cairo in 1964 and the abortive “Bandung II” at Algiers in 1965. As several historians have shown, US diplomats played active roles behind the scenes before and often during each of these conferences. In general, these efforts followed a pattern. In advance of each conference, US officials viewed the prospective gathering as a threat with the potential to bring together anti-white, anti-Western, anti-imperialist, and anti-capitalist currents hostile to the United States and its allies. Washington feared that its most ardent antagonists in the Third World – above all the People’s Republic of China but also at times Castro’s Cuba, Ben Bella of Algeria, Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, and Indonesia’s Sukarno – would use the conference to try to unite the Third World behind a radical agenda inimical to US interests and turn it into a forum for propaganda and denunciation of the United States and its allies.

After considering, but discarding, the feasibility and desirability of trying to prevent the conferences from ever taking place by discouraging participation by governments sympathetic to US views, officials adopted (to varying degrees) a strategy of engagement with each conference to try to moderate its tone and outcome by ensuring that pro-Washington and pro-Western delegations attended and made their voices heard. US diplomats worked with and through sympathetic governments to shape the roster of invitees, the agenda and rules of procedure, and the tone of the eventual resolutions and declarations in order to minimize criticism of the United States and its allies, albeit with varying degrees of vigor and success. In the aftermath of each conference, US officials expressed relief that, from their point of view, things could have been worse. Washington was particularly sanguine in late 1965 given the fallout from the aborted Bandung II at Algiers; Johnson administration officials believed that their subtle but vigorous, behind-the-scenes diplomatic efforts to thwart the Sino-Indonesian push to radicalize Third World internationalism had been effective. “Moderate” and pro-US voices in the Third World had prevailed over the militant Afro-Asian left wing led by Beijing and Jakarta.Footnote 4

The actions of the Johnson administration in response to the Tricontinental Conference would be largely consistent with the pattern set at these previous conferences. The Tricontinental presented the US government with both a revolutionary threat and a counterrevolutionary opportunity, and Washington responded with another vigorous but largely behind-the-scenes diplomatic effort to meet the challenge and exploit the opportunities it presented. The core of this strategy was to exploit the political and ideological divisions among the movements represented at Havana, largely indirectly and by proxy, in order to undermine the Tricontinental solidarity movement and isolate and harass Washington’s enemies. While US officials considered their counteroffensive to be largely successful in short-term diplomatic and material terms, the push for Tricontinental revolutionary solidarity nevertheless highlighted the long-term challenges that Washington faced in seeking to suppress liberation movements across the Third World.

Anticipating Conflict

Infighting along ideological, methodological, and regional lines had plagued AAPSO, and Third World revolutionary internationalism more broadly, ever since the late 1950s. At the heart of this struggle was the Sino-Soviet contest for leadership of the global revolution. The gradualist strategy of “peaceful coexistence,” economic competition with the capitalist West, and the gradual achievement of socialism practiced by Moscow and the orthodox communist parties of Europe and Latin America conflicted with the more confrontational line of revolutionary armed struggle and militant anti-imperialism advocated by China, Maoist-inspired movements in Asia and Africa, and Fidel Castro and Che Guevara in Latin America.Footnote 5

The potential for discord increased with the projection of AAPSO and ideological competition into Latin America. The Latin American Left in the 1960s was being simultaneously reinvigorated and fragmented by the victory of the Cuban Revolution and the export of Castro and Guevara’s program of guerrilla warfare and revolutionary confrontation to the continent. The region’s established orthodox communist parties continued to adhere to Moscow’s gradualism but were challenged by new or splinter factions favoring direct guerrilla confrontation as advocated by Havana and Beijing. In a few cases, these more confrontational groups received material and ideological support from Havana. The deepening divisions prompted the Soviets and Cubans to convene a secret summit of Latin American communist parties in Havana in November 1964. Castro pledged to cease his rhetorical attacks against the orthodox parties, while Havana and Moscow pledged to increase their own support for the liberation struggle. The Tricontinental Conference would mark the culmination of these internal tensions and the efforts to overcome them within the Latin American and world communist movements, as the Cuban government continued its efforts to build and radicalize a coalition that united Second and Third World governments and nonstate movements behind a militant revolutionary program.Footnote 6 It also came amid the period of most severe diplomatic and economic isolation for Cuba in the hemisphere, following its recent suspension from the Organization of American States (OAS), the imposition of an OAS-wide economic embargo, and the rupture of diplomatic relations between Havana and all the governments of the hemisphere save Canada and Mexico. It came, too, at a time when the Cuban government – economically dependent on the Soviet Union but ideologically more compatible with the Chinese and eager to see like-minded movements come to power in the hemisphere – found its balancing act between the two communist giants increasingly difficult.Footnote 7

In response to the public revelation of the November 1964 Havana communist summit, US policymakers anticipated an increase in insurgent activity in the hemisphere, as Moscow sought to blunt Chinese and Cuban criticism and reassert its leadership of world revolution by more tangibly backing Latin American guerrillas.Footnote 8 The CIA predicted that Castro “personally attaches great importance” to the Tricontinental Conference and intended to use it to assert leadership among Third World liberation movements and ameliorate Cuba’s diplomatic and economic isolation.Footnote 9 The Agency also predicted that “fireworks resulting from the Sino-Soviet dispute may well seriously disrupt the conference,” but that it would nonetheless offer “a ringing indictment” of US policies.Footnote 10

Washington had monitored the effort in spring 1965 – spearheaded by Castro’s government in cooperation with its closest Third World ally, Ben Bella’s Algeria – to overcome the Sino-Soviet and other rivalries within AAPSO in order to proceed with the process of convening a tricontinental solidarity conference in Havana.Footnote 11 After the Johnson administration intervened in the Dominican Republic, Secretary of State Dean Rusk acknowledged in a cable to embassies in Latin America in early May that the “situation obviously provides exceptional springboard for conference propaganda on colonialism and imperialism, and most timely for AAPSO objective of extending its activities and influence in Latin America.”Footnote 12 Rusk instructed diplomats in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, meanwhile, “to expose this meeting for what it really is and whom it actually represents,” that is, the most extreme and dangerous elements of their countries’ political milieu. While “informal discussions” with local officials and other opinion leaders could be useful in this effort, Rusk instructed that this task should be carried out “preferably where possible through unattributable items in local media,” in order to reach a broader public.Footnote 13

The perceived gains from the Bandung II debacle at Algiers and the other critical Afro-Asian developments in the second half of 1965 do not seem to have fundamentally altered the US views of or approach to the impending Tricontinental. In December 1965, Undersecretary of State George Ball cabled all US embassies to instruct them to communicate with their host governments in order to expose the conference “for what it really is and whom it actually represents,” while at the same time to “avoid building up or stimulating [public] interest in the Conference.” Explaining these instructions, the cable predicted that, “The conference will be an anti-West, particularly anti-U.S., propaganda forum” that would denounce Washington for its support of reactionary governments in Rhodesia and the Congo, its embargo against Cuba, its escalating war in Vietnam and recent occupation of the Dominican Republic, and its “racial problems” at home. While Castro was expected to project his own leadership of the Third World and the Latin American Left, the Soviets would seek to do the same, outflanking the Chinese in the process. Beijing, meanwhile, was expected to try to block the proposed merger of AAPSO into a single Tricontinental organization, since the addition of the pro-Moscow Latin American communist parties would dilute Chinese influence in the Afro-Asian bloc.Footnote 14 Therefore, before the conference began, Washington, while acknowledging its own vulnerabilities, had spotted potential weaknesses in the incipient Tricontinental movement and begun to foment opposition.

“Noise” and “Practical Results”

In its critique of the geopolitical situation, the conference played out much as US observers predicted.Footnote 15 While celebrating that formal colonialism had retreated from most of Asia, the Middle East, and Africa, the conference called for the overthrow of the remaining Portuguese, British, and French colonies and of the white settler regimes in South Africa, Rhodesia, and Israel. The conference also denounced the turn to neocolonial economic exploitation and political control of Third World peoples through “reactionary” client governments and militaries in countries such as Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, Guatemala, the Congo, and Thailand.Footnote 16

While denouncing European colonialists, white settlers, and local collaborators, the Tricontinental aimed its main critique at the United States. Surprising the US National Security Council staff with his militancy, Cuban President Osvaldo Dorticós told the assembled delegates in his welcoming speech that, “U.S. imperialism, the center of world reaction and the foremost enemy of peace and progress, unscrupulously carries out within the framework of a perfectly defined world strategy, any number of openly criminal actions.” Washington, he said, funded and trained counterinsurgency forces; sustained Portuguese, South African, and Israeli colonialism; continued its efforts to overthrow the Cuban Revolution; and intervened militarily in Vietnam and the Dominican Republic.Footnote 17 Accordingly, the Conference’s General Declaration proclaimed: “To destroy the domination of Yankee imperialism is an imperative issue for the complete and definitive victory of the anti-imperialist struggle in the three continents, and all efforts of the peoples should converge toward this aim.”Footnote 18

Caught up in the revolutionary spirit and pressured by militant hard-liners, the Tricontinental delegates declared that globally coordinated armed struggle was the primary means to defeat Yankee imperialism. The militants prevailed in a hotly contested “Resolution on Peaceful Coexistence,” which restricted this concept of relations between socialist and capitalist states, denied that coexistence was possible between imperialists and their victims or between the working and capitalist classes, and upheld the right of oppressed peoples to fight against their oppressors and to receive aid from others in their struggle.Footnote 19 The vote represented a victory for advocates of militant revolution such as the Cuban hosts and the Maoists, who rejected the gradualist Soviet vision of international revolution and favored instead a newly assertive brand that combined traditional Marxist readings of class warfare with a specifically Third World anti-imperialism. Pushing this more assertive reading of international revolution, Castro closed the conference with a two-hour speech in which he argued, “sooner or later all, or nearly all, of the peoples will have to fight, arms in hand, for their liberation.”Footnote 20 The CIA called it Castro’s “most explicit call for armed revolution” since his 1964 modus vivendi with the pro-Soviet parties and warned of “renewed Cuban interest in insurgent activities throughout the hemisphere.”Footnote 21

The State Department noted the increasing theoretical divergence between the more measured revolutionary approach of the Soviet Union and the more aggressive rhetoric of Third World anti-imperialists led by Cuba and China. But in the words of a cable from Undersecretary Ball, the department saw this rhetorical battle mostly as “noise.” Washington’s focus moving forward was on the potential “practical results” of the Havana conference that could tangibly threaten US interests.Footnote 22 These included the creation of a Committee of Assistance and Aid to the National Liberation Movements – tasked with providing “moral, political, and material aid” to world revolutionaries – and a Tricontinental Committee for the Support of the Vietnamese People.Footnote 23 The twenty-seven Latin American delegations moved to support revolution in the hemisphere by creating a Latin American Solidarity Organization (Organización Latinoamericana de Solidaridad, OLAS), headquartered in Havana, to hold its inaugural meeting in 1967.Footnote 24 The new OSPAAAL secretariat, to be constituted in Havana, was to coordinate all these revolutionary efforts on a global scale and prepare for a Second Tricontinental Conference in Cairo in 1968.Footnote 25

From Washington’s point of view, however, the most important practical outcome of the conference was its demonstration of the deepening fissures in the socialist world. Ball perceived the “Sino-Soviet dispute visible in all proceedings” and noted that the “speeches by Soviet and Chinese delegates, as well as respective allies, [were] loaded with barbs and recriminations as two big powers struggled for domination.” Many African and Arab delegations, meanwhile, were upset at the perceived neglect of their interests, according to the Department’s intelligence reports.Footnote 26

A Global Counteroffensive

In response to the Tricontinental Conference, the US State Department launched a sophisticated and ultimately successful diplomatic effort to exacerbate those same divisions in order to discredit, divide, and undermine the Tricontinental project around the world. For the State Department, the Tricontinental Conference was as much a counterrevolutionary opportunity as a revolutionary threat. As recounted in the department’s internal history of the period, and confirmed in the archival record, this counterrevolutionary effort had three main objectives. First, the Department endeavored to arouse anger in Latin America and the rest of the “Free World” in order to use the Tricontinental as a pretext for deepening Cuba’s diplomatic and economic isolation, on the basis that Havana aspired to become a revolutionary base that could threaten noncommunist governments everywhere. Second and more successful was the effort to peel the Egyptian regime off from the Tricontinental coalition and abort the Second Tricontinental Conference scheduled for Cairo in 1968. Third, the principal and most elaborate effort was to use the OAS and United Nations (UN) as international fora to denounce the Tricontinental and exert diplomatic pressure on the Soviets. “The US basic tactic” in all of these efforts, the internal history states, “was to remain in the background and say little publicly, while quietly stimulating Latin American and other criticism and action against communist sponsors and participants. … [I]t was particularly important to make certain that Latin American protests appeared as totally spontaneous, rather than as arranged or prompted by us.”Footnote 27 Adopting these goals and tactics, ironically, the US government essentially conformed to the Tricontinental’s depiction of US foreign policy as neocolonial and counterrevolutionary.

On January 21, 1966, as delegates made their way home from Havana (often clandestinely via third countries), Secretary Rusk cabled US embassies in Latin America, instructing them to suggest that their host governments put pressure on West European and Japanese governments to conform to the OAS embargo and curtail their trade with Cuba. The Tricontinental, they were to argue, highlighted the “basic inconsistency” between “free world” countries’ trade and development programs in Latin America and their simultaneous trade with Cuba, which was indirectly funding the “disruption” of those same Latin American countries. United States diplomats were to suggest that Latin Americans pressure the Free World’s holdouts to purchase sugar from other sources and to deny Cuba access to credit and agricultural, transport, and communications equipment.Footnote 28 Rusk followed up individually with embassies in Guatemala City and Lima.Footnote 29 The absence of subsequent documentation suggests that this initiative did not amount to much, but the intent is indicative of the US effort to use the Tricontinental to further isolate and impoverish Castro’s Cuba.

More sustained and successful was State’s effort to drive a wedge between the Egyptian government and the rest of the solidarity movement. The AAPSO had been founded and headquartered in Cairo, and AAPSO Secretary-General Yusuf al-Siba’i had ties to the Egyptian regime of Gamal Abdul Nasser. Nasser’s government, however, had grown increasingly disillusioned with AAPSO as Marxist sectarianism and Sino-Soviet infighting came to dominate the organization.Footnote 30 Egyptian discomfort deepened when the solidarity project’s extension to Latin America threatened governments with which Nasser maintained friendly relations. The US ambassador in Cairo, seeing Egypt “reconsidering” its support for the movement, met with several Latin American diplomats in Cairo and “suggested timely representations might encourage this promising development.”Footnote 31 Agreeing with the Colombian Foreign Minister’s determination that “Nasser should be made to eat crow in some way” for his role in supporting Cuba and regional leftist movements, Undersecretary Ball instructed all Latin American posts to facilitate confrontation between their host governments and the Egyptians, while taking care to “avoid impression US taking initiative.”Footnote 32 Ball believed that “stern LA reaction would serve as salutary lesson to such chronic meddlers as Nasser and Nkrumah that they cannot with impunity support commie inspired intervention in LA or elsewhere as advocated in Tricon.”Footnote 33 United States diplomats provided the supporting documentation behind several Latin American governments’ formal protests.Footnote 34 Time would tell if the US-orchestrated pressure on Nasser would yield more significant results.

While working behind the scenes to isolate Cuba and Egypt, State maneuvered in similar ways against the Soviet Union, working through the Latin American delegations in the OAS and the UN. These moves, initiated while the Tricontinental delegates were still in Havana, sought to catch the Soviets in even greater contradictions than the Egyptians; not only had well-connected ruling party affiliates attended the conference, but in Moscow’s case they had also publicly pledged – in contrast to their secret agreements at the 1964 Havana communist conference – to support the armed ouster of Latin American governments with which the Soviets maintained official diplomatic relations. Sharaf Rashidov, head of the Soviet delegation, was First Secretary of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan and an alternate member of the Presidium of the Central Committee in Moscow.Footnote 35 At the Tricontinental, Rashidov pledged “our fraternal solidarity with the armed struggle of the Venezuelan, Peruvian, Colombian, and Guatemalan patriots against the lackeys of imperialism.”Footnote 36 It was a contradiction that the US government would productively exploit over the course of 1966.

The United States did not initiate the idea of action through international organizations; rather, the initiative can be traced to the Peruvian government, which requested and received US support for action at the OAS and UN in an exchange of letters begun on January 15.Footnote 37 But State seized the opportunity provided by the Peruvian initiative and worked to broaden and intensify Latin American governments’ condemnation of the conference and of the Soviet role in particular. The US embassy in Lima and US representatives at the OAS and UN encouraged the Peruvians to launch formal protests and to bring in other regional governments as co-sponsors.Footnote 38 After (as Ball wrote) “cooperating with Peruvian del[egate] to OAS in developing his presentation,” US diplomats looked on approvingly as Peruvian Ambassador to the OAS Juan Bautista de Lavalle decried the conference and called for a special meeting of the OAS Council for January 24.Footnote 39 At that meeting, Lavalle took the lead in denouncing the Tricontinental as a whole and Soviet support for subversion in the hemisphere in particular. He submitted a resolution, drafted by the State Department, to have an OAS committee investigate the conference and refer the results to the UN.Footnote 40

Radio Havana belittled the OAS as “the Yankee ministry of colonies,” claimed that the “hysterical response from the North American imperialists and their obliging Latin American lackeys” was “to be expected,” and vowed that the Tricontinental’s resolutions would be carried out.Footnote 41 While knowing better than anyone the degree of truth behind Havana’s invective, National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy approved of the direction the Tricontinental’s aftermath was taking. Bundy wrote to President Johnson of the “most welcome development” of the Latin Americans’ action at the OAS and informed his boss, “We are encouraging them in these moves and capitalizing on the propaganda advantage which the Havana meeting affords … We are working to get editorials and articles published in our press, as well as the Spanish editions of Life and Reader’s Digest. Through State and US I[nformation] A[gency], materials on the meeting will be reaching friendly editors, columnists, and writers” throughout the region.Footnote 42 In at least one case – that of Uruguay – a USIA-produced documentary on the conference aired on prime-time television.Footnote 43 From the highest levels in Washington down to Latin American newsstands and living rooms, the counterrevolution in the international public sphere was in full force within weeks of the Tricontinental Conference.