But what harm is there in diversity, when there is unity in desire?

By the early 1960s, a vociferous and coordinated critique of Western hegemony dominated political discourse across the Southern Hemisphere. So, it was hardly surprising when the prime minister of newly independent Algeria, Ahmed Ben Bella, addressing the United Nations General Assembly on October 9, 1962, firmly situated his country in this globe-spanning “Third Worldist” movement challenging the political and economic status quo. “In the structure of the contemporary world,” he said, “Algeria is allied with an ensemble of spiritual families who, for the first time at [the 1955 Bandung Asian-African Conference], recognized the shared destiny that unites them.” He vowed that Algeria would help in pursuing their shared goal of tearing up the “gentleman’s agreements” (an expression commonly used in Algerian diplomatic communications at the time) by which the victors of World War II, chief among them the United States, created the structures that formalized and perpetuated their supremacy.

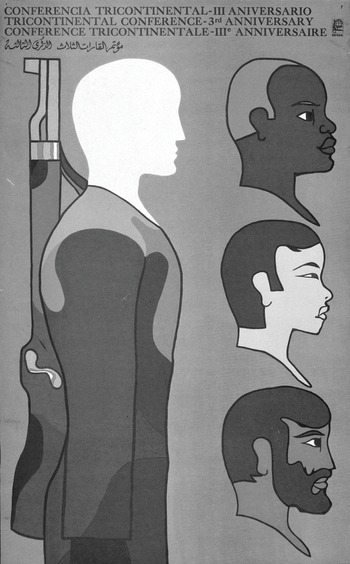

Figure 6.1 A central tenet of Tricontinentalism was the interlinked revolutions of the three continents, which appeared in the iconography as unity between peoples of various non-white races. Even as states like Algeria moved away from direct invocations of militarism, the idea of multiracial struggle remained central to various political and economic challenges to the international system. OSPAAAL, Alfredo Rostgaard, 1968. Offset, 54x33 cm.

Referencing Algeria’s own long and bloody war for independence from France between 1954 and 1962, he positioned his country in the more militant wing of that “spiritual family.” Insisting that the Algerian revolution had “surpassed its national context in order to serve, henceforth, as a point of reference to all peoples still under colonial domination,” Ben Bella dedicated his government to the eradication of colonialism “in classic or disguised form,” pointing to nationalist struggles in places like Palestine and Angola as examples. He cautioned his audience against mistaking the high-minded and pacific doctrines of non-alignment and Afro-Asianism for policies of passivity; on the contrary, Ben Bella vowed, Algeria would be a responsible and engaged country “[f]or every concrete decision concerning major international problems, peace and global security.”Footnote 2 As tangible proof of his active and “engaged” intent, Ben Bella traveled from New York to meet with John F. Kennedy at the White House before traversing the most dangerous Rubicon in international affairs – the 100 miles or so separating the United States from Cuba – in order to greet Fidel Castro as a revolutionary brother. Of course, nobody in the General Assembly Hall that day, least of all Ben Bella himself, realized that his first foray abroad would directly implicate his country in the incipient Cuban Missile Crisis.

Reporting on the speech and Ben Bella’s interactions with the diplomatic community in New York, Western officials expressed general skepticism about Third Worldist rhetoric in general, as well as war-ravaged Algeria’s ability to live up to its leaders’ ambitious international agenda. A British observer condescendingly attributed Algerian ardor to the “first flush of enthusiasm” after independence. He suggested that with “the spotlight of Afro-Asian attention … still very much on them … [the Algerians] no doubt feel it necessary … to live up to their reputation as fighters for freedom and to be that much more extreme in order to impress their Afro-Asian colleagues.”Footnote 3 Kennedy’s key advisor on the developing world, Robert Komer, expressed a similar tone a few days later when he briefed the president for the Algerian premier’s visit. Warning that Ben Bella “still clings to a lot of naive ideas and thinks in terms of a melange of revolutionary clichés from Marx, Mao, Nasser and Che Guevara,” Komer nonetheless judged that “basically … he’s much more pragmatic than doctrinaire.” Komer believed that a pressing need for American economic assistance and food aid would soon temper Ben Bella’s bellicosity.Footnote 4 United States officials felt that the Algerian government ought to dedicate itself to domestic concerns, not throw itself into ambitious plans to change the nature of international affairs.

But that is not what happened. Not only did the Algerians continue to push, fairly successfully, for an appreciable and disproportionate measure of influence in international affairs, but they were also unbowed by the diplomatic fallout from the Missile Crisis. Their warm relationship with Cuba quickly became an important – and controversial – facet of both countries’ relations with the wider world. Algiers and Havana were advocates for one another in key diplomatic contexts; they also cooperated closely in transnational revolutionary training and subversion. Their ruling cliques had many traits in common: commitment to socialism, enthusiasm for supporting armed liberation and revolutionary movements in any part of the globe, and the desire to use the many organizing themes of Third World solidarity – Afro-Asianism, Pan-Africanism, non-alignment, and others – to surmount their own sense of local confinement and ideological isolation. Algiers sought to host the Second Afro-Asian Summit, or what they referred to as “Bandung II,” in 1965, just as Havana hosted the Tricontinental Conference the following year. In fact, one of the main orchestrators of the 1966 Tricontinental Conference, Moroccan leftist Mehdi Ben Barka, was an intimate ally of the Algerian revolutionaries. (Ben Barka, infamously, was assassinated in still-murky circumstances in Paris before he could preside over the Havana Conference, as intended.) When Morocco briefly attempted to alter its border with Algeria by force of arms in November 1963, Fidel Castro immediately dispatched a Cuban tank unit to buttress Algeria’s own armed forces. All told, throughout the early and mid-1960s, Cuban-Algerian Transatlanticism was one of the most substantive manifestations of Third Worldism’s much-ballyhooed expansion from Asia and Africa into Latin America.

Yet the Algerian-Cuban relationship also reflected many of the complexities and contentions within the Third World solidarity movement. In their public diplomacy, postcolonial and Third World governments tended to formulaically invoke multiple expressions of solidarity – Afro-Asianism, non-alignment, Pan-Africanism, Pan-Arabism, and so on – which Western observers often interpreted as evidence of excessive ambition and insufficient substance. But such rhetoric reflected a desire to avoid publicly airing the many divergences of interest and priorities within the Third World; holding together a loose coalition of scores of countries necessitated some waffling diplomacy that did not always do justice to the seriousness of the participants’ intent. None were more conscious than the Algerians of the need to make Third Worldism an effective foreign policy doctrine, which by necessity entailed real disagreements as well as real accomplishments. Often portrayed as an impetuous and unrealistic dreamer, Ben Bella himself was quite aware of the need to translate sweeping expressions of transnational solidarity into concrete supranational frameworks and bilateral gestures. Prior to his trip to the Americas in October 1962, which was rightly expected to be controversial even without knowledge of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba, he told Algeria’s national assembly that “[f]or it to be effective and positive, neutralism must not be limited simply to statements of principle. The non-aligned countries must establish and develop a real solidarity between them, as much in the political domain as in the economic domain.”Footnote 5 Privately, Algiers’s diplomats deliberated over the actual meaning and relative urgency of each of the many expressions of solidarity that they publicly committed themselves to, including Arab, African, Afro-Asian, and Maghrebi (North African) solidarity projects, among others.

The Cuban-Algerian alliance in the early 1960s was a form of revolutionary solidarity that was a direct precursor to the Tricontinental Conference. Cuba and Algeria’s willingness to cooperate closely in exporting armed revolution around the world was one of the most prominent and celebrated forms of Third World internationalism. However, it provoked criticism and controversy even within the postcolonial world. Cuban and Algerian support for armed revolutionary movements, especially those operating in African and Latin American countries that were objectively independent sovereign territories (rather than colonies), made many Third World elites nervous. India was the most prominent and powerful critic of support for guerrillas and terrorists, but other Latin America, African, and Asian governments agreed. Respect for national sovereignty and noninterference in one another’s internal affairs was arguably the core principle of all Third Worldist diplomacy, prominent in all declarations by the Non-Aligned Movement and other such entities. Many saw how slippery a slope it was when the most radical countries, like Algeria and Cuba, argued that the compromised “neocolonial” status of some independent Third World countries – such as Congo under Moishe Tshombe in the early 1960s – legitimated fostering revolutionary activity in those territories without violating the principle of noninterference.

Additionally, the focus of Third Worldist diplomacy shifted markedly in the late 1960s and early 1970s toward global economic questions, rather than anti-colonial struggle. In that respect, the Tricontinental Conference’s continued emphasis on revolution and political liberation was reflective of a concern that was gradually becoming a more marginal facet of international affairs in the Southern Hemisphere. The shift in focus toward economic affairs also brought Latin America firmly into the Third World coalition. With significant Latin American (but not Cuban) participation in the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), established in 1964, tensions between Cuba and some of its regional neighbors became a more prominent dynamic in Third World politics in the late 1960s and 1970s. While Cuba had been a participant in the founding of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) in Belgrade in September 1961, even the Algerians discreetly, if sympathetically, recognized that Cuba was emphatically Soviet aligned in Cold War terms. Consequently, the participation of Cuba in wider Third World meetings and associations generally required some diplomatic finesse, lest it be used to discredit non-alignment altogether. Last, Cuba’s membership in the communist world was an even greater concern when the communist countries’ internecine schisms and ideological battles, above all the Sino-Soviet split, threatened to pollute and spoil all attempts at Third World mobilization. The large majority of developing countries with no investment in such doctrinal disputes came to greatly resent communist bickering in the 1960s.

Algerian-Cuban friendship and the Tricontinental Conference of 1966 must be understood in this context. In many respects, the Tricontinental Conference marked the conclusion of the romantic era of decolonization, which Cuban-Algerian solidarity from 1959 to 1965 had exemplified. While they remained important partners in various Third World initiatives, in the late 1960s, there were increased divergences between Algiers and Havana that reflected divergences within postcolonial international affairs more broadly speaking. Algeria was a fine example of a country that was invested in the system, even if it sought to dramatically reform it. Like many postcolonial countries, Algeria sought to balance its support for the ongoing process of eliminating imperialist structures with the need to support an international system that was, ultimately, the guarantor of national legitimacy. By the 1970s, the global battle against imperialism was pursued chiefly by negotiators armed with briefcases and professional degrees, arguing over the global terms of trade and seeking to cast regimes like that in Pretoria as pariahs violating received morality. Cuba, in contrast, besieged by the United States and subsisting on Soviet benevolence, remained more stubbornly revolutionary and defiant of international norms. In the 1970s, Cuba’s support for the anti-colonial struggle abroad even progressed to the deployment of Cuban troops in significant numbers to places like Angola, Syria, and the Horn of Africa. In many respects, these initiatives were tremendous successes, but the perceived necessity of those direct interventions also undermined the narrative of historical inevitability that had powered anti-colonial struggle in previous decades. The very mixed record of the nationalist movements that featured prominently in the years of the Cuban-oriented Tricontinental – including cases like Angola and Mozambique, that suffered decades of civil war, or Western Sahara and Palestine that appear, as of the time of writing, simply to have failed – is poor in comparison to the 1940s–60s. A comprehensive autopsy of the Third World has yet to be performed, but an examination of Cuban-Algerian relations in the run-up to the Tricontinental Conference of 1966 sheds some light on how the era of anti-colonial romance ended, and how various divergences within the Third World project contributed to future disappointments.

The Example of Cuban-Algerian Transatlanticism

After independence, one of Algeria’s most insightful and successful strategies was to take advantage of its position at the intersection of multiple regions and geopolitical entities. The country bridged the Arab world and sub-Saharan Africa; considered part of metropolitan France for much of the colonial era, it also connected the two shores of the Mediterranean. Thus Yasir Arafat, cofounder of the Palestinian nationalist group Fateh, described Algiers in 1962 as the “window through which we appear to the West,” while a senior official in Paris advocated productive postcolonial relations on the basis that Algeria could be France’s “narrow doorway” into the Third World.Footnote 6 In addition to these historical connections, an activist vision of Cold War neutrality also encouraged Algeria and many other Third World countries to connect with both sides of the age’s great ideological divide. Proclaiming themselves determined socialists (for the most part), Algeria’s new leaders also decided that their country’s future prosperity necessitated deepening and diversifying (in the sense of diluting France’s overbearing role as a source of trade and development assistance) their economic ties to the West. It was entirely consistent, therefore, that Algerian diplomats called for convergence within the Third World space: for the Afro-Asian and non-aligned groups to merge, for Arabs to support Southern African liberation movements, for all Africans to support Palestinians, and indeed, for Latin America to be included fully in the Third World project. With this in mind, Algeria became probably Cuba’s most important connection to Africa in the first half of the 1960s.

Even before the conclusion of the war in Algeria, the Algerian and Cuban revolutionaries had formed an enthusiastic bond in a remarkably short time, and with remarkably little direct interaction or exchange between them. From the very first encounter, in Cairo in early 1959, between a representative of the new Castro regime and those of the Algerian Front, the latter spoke of an instant sense of warmth, fraternity, and mutual recognition between true revolutionaries. A year later, the FLN’s first visitor to Cuba wrote rapturously of the experience for the movement’s main newspaper, El Moudjahid. “Under the sky of Cuba, pearl of the Antilles,” he enthused, “in this Caribbean Sea lapping the equatorial shores of the South American continent, we have felt the ardent and fraternal hearts of millions of citizens, freed from the yoke of odious dictatorship, beating in unison with the Algerian Revolution.”Footnote 7 If the demands of propaganda urged a poetic turn, the effusive substance of his piece was in fact wholly consistent, for the most part, with the Algerian revolutionaries’ private, internal deliberations. Many cadres in the FLN’s political apparatus saw Cuba’s revolutionary project as an example for independent Algeria to follow in the social and economic spheres (albeit without going so far as to embrace outright communism), while also admiring the commitment to exporting revolution across the Latin American continent.Footnote 8 Could not Algeria be the “Cuba for Africa”? they asked, emphatically answering in the positive. Indeed, their widespread enthusiasm for Fidel Castro’s Cuba is all the more notable for the fact that, in reality, Havana took only modest steps to demonstrate its solidarity with the Algerian cause, for fear of stoking the hostility of France as well as the United States. While the FLN leadership celebrated Castro’s government for the largely symbolic gesture of taking in some Algerian refugees, they complained incessantly about the supposed inadequacy of the far more significant (and costly) support that they received from Arab governments such as Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia.

Officers in the FLN’s military bases in Tunisia soon started to imitate the Cuban revolutionaries’ distinctive look by regularly wearing combat fatigues accessorized with pistols and even cigars. As would occur in student dorm rooms across the West, Cuban revolutionary posters and other paraphernalia proliferated in some of these bases. It is easy to mock these stylings, as some members of the FLN did, and to see a certain shallowness to such demonstrations of anti-imperialist solidarity and Third World internationalism.Footnote 9 But the early years of the Algerian-Cuban relationship show how the limits of such interactions – in truth, the two sides barely knew a thing about each other’s countries or histories – did not curtail the intensity or significance of the sentiment. The relationship, however superficial, offered a sense of solidarity and reinforced the distinct revolutionary goals of two countries forging precarious paths in hostile environments. After all, in decolonizing Africa and the Middle East, dress and affection could be fraught and contested signifiers of cultural and political loyalties, or values.Footnote 10 Notably, FLN military bigwig Houari Boumédiène and his lieutenant, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, were two of the Front’s most prominent Cubanophiles in the last years of the war. After independence, the former became the minister of defence and the latter the foreign minister, and they subsequently orchestrated the successful coup that saw Boumédiène supplant Ben Bella in 1965.

Perhaps it was partly with a mind to appeasing such constituencies that Ben Bella took the dramatic decision to visit New York, Washington DC, and Havana in sequence in mid-October 1962, thereby unintentionally enmeshing independent Algeria’s triumphant debut in world affairs with the hazardous acrimony of the Cuban Missile Crisis. It was at least equally important, however, to demonstrate the sincerity of Algeria’s bold pronouncements on international affairs. While Ben Bella did not know that he would be meeting President John Kennedy at the White House on the same day that CIA analysts were poring over surveillance photographs of Soviet nuclear missiles deployed at his next port of call, he had certainly intended to flout one of the Cold War’s most heated lines of fracture. The conversations between the Algerians and Americans during this trip directly addressed the fundamental issues of the Cold War in the Global South. On the one hand, the White House hoped that the Algerians would see Cuba as a warning of the perils of “Communist capture of indigenous national revolutions.”Footnote 11 But Ben Bella’s first foreign minister, Mohamed Khemisti (who was succeeded after his death several months later by Bouteflika), encapsulated his side’s outlook by defending Cuba’s right to pursue its “economic and social liberation” and criticized the United States for attacking the regime “chosen by the friendly people of Cuba.”Footnote 12 Cuba’s choice of communism, in the Algerian view, was first and foremost an expression of national sovereignty (the questionable reality of it being a free “choice” notwithstanding). This disagreement encapsulated the perpendicular divergence of perspectives between much of the Third World and the Kennedy administration: for all of Kennedy’s genuine concern for the plight of the developing world, his sympathies could not exist outside of the Cold War paradigm. Moreover, the Cubans were greatly appreciative of their Algerian guests’ willingness to endure Washington’s ire by defying American efforts to isolate the island. Although the Kennedy administration accepted the Algerians’ innocence with regards to the nuclear threat in Cuba, Ben Bella’s trip to Havana unquestionably came at a cost.

Cooperation between Algiers and Havana flourished in the wake of the Algerian delegation’s October 1962 visit. Fidel Castro appointed Jorge Serguera to the new embassy in Algiers the following February, and Serguera arrived declaring that his role was not that of a traditional ambassador, but rather a revolutionary ally and “extra combatant in the service of Algeria.”Footnote 13 At Havana’s request, Ben Bella and Boumédiène agreed to take in a small group of Argentinian guerrillas-in-training who had overstayed their welcome in Prague, adding to a list that already included key leaders in African revolutionary movements from South Africa, Mozambique, and elsewhere in the continent. Shortly after, Algeria also received a delegation of the Venezuelan National Liberation Front and agreed to ship armaments to them across the Atlantic.Footnote 14 Operating under shell companies, an Algerian cargo vessel, the Ibn Khaldun, provided a circuitous yet effective supply line to Venezuela, thereby bypassing the United States’ close surveillance of Cuba’s efforts to export revolution.Footnote 15 In May, a grateful Castro sent a team of more than fifty doctors and nurses to help alleviate Algeria’s severe health crisis and shortage of medical personnel. Visiting Moscow that spring, the Cuban leader urged Nikita Khrushchev to extend support to Algeria and to see the North African country as a properly revolutionary one that could well follow the Cuban example. Algiers took further action to alleviate Cuba’s isolation by agreeing, in June, to serve as a refueling stop for Soviet aircraft bound for the Caribbean, which necessitated the enlargement of several runways with Moscow’s assistance.Footnote 16

Thus, the Cuban-Algerian relationship was quickly becoming very close in both substantive and atmospheric terms. When Guevara spent three weeks in Algeria in July, he received a rapturous reception in public and political circles alike. Essentially given license to wander at his leisure, the Argentinian enthused that “each time I see something new in Algeria, I am reminded of Cuba: there’s the same esprit, the same enthusiasm, the same inexperience too.”Footnote 17 It was a reflection of the unapologetic nature of the Cuban-Algerian friendship that US Senate Majority leader Mike Mansfield, who was also visiting Algeria at that time, unwittingly found himself attending a state function on July 5th, the anniversary of Algerian independence, that featured Guevara and Egypt’s Marshal Abdel Hakim Amer as joint guests of honor. The politically powerful senator was displeased to see his hosts fete the poster child of a revolution that, scarcely half a year prior, had threatened to obliterate his own country.Footnote 18 Unsurprisingly, Algerian requests for economic aid and commercial deals were meeting sizable and growing opposition in Washington.

By provoking Washington’s ire, the Algerian government showed that it was willing to pay a significant price for its friendship with Cuba. On more than one occasion, State Department analysts confessed to being baffled by the Algerians’ motivations, for they could see little benefit for Algeria in meddling in the controversies of another continent, half a world away.Footnote 19 Nevertheless, the Algerians’ motivations do seem to have stemmed from the principles of revolutionary and anti-imperialist solidarity that American officials found hard to accept at face value; their internal records do not contradict their public statements in this regard. There was a clear ambivalence in the Algerian government’s attitude to the United States: on the one hand, Algiers saw Washington as the most feasible alternative and competitor to France as a source of trade and development assistance; yet at the same time, Algerian officials consistently described American economic and strategic interests in the Third World as the most powerful and dangerous manifestation of “neo-imperialism.” To the extent that cooperation with Cuba was pragmatic, the leaders of both governments believed that they could defend themselves best from American hostility by encouraging revolution elsewhere in Africa and in Latin America, which distracted Washington and created new allies for them. In any case, Algeria’s friendship opened new vistas for Castro and his comrades. If Serguera was perhaps exaggerating the significance of the initial Cuban-Algerian subversive collaboration in Latin America by describing it as a breakthrough for the Afro-Asian world and a pioneering example of anti-imperialist solidarity, this unquestionably bold decision by Ben Bella’s government would lead to more cooperative ventures of a similar nature in the near future.Footnote 20 Likewise, as historian Piero Gleijeses has noted, besides strengthening the two countries’ alliance, the medical mission in Algeria proved to be important to the history of Cuba’s international relations because it was the first actual implementation of Havana’s rhetorical commitment to humanitarian internationalism – the beginning of a long and proud tradition of providing assistance to other developing countries.Footnote 21

Probably the most significant area of cooperation between Algeria and Cuba concerned supporting revolutionary and liberation movements in one another’s continents. Algeria had a similar relationship with Yugoslavia, a country that in some respects shared Cuba’s dilemma of being relatively isolated in its own region. In this period, the Algerians brought their Caribbean and Balkan allies into the self-identified revolutionary wing of postcolonial African politics, which included the likes of Egypt, Ghana, Mali, and Tanzania.Footnote 22 Countries such as these were more unrestrained than some of their African peers in supporting armed subversive movements. Cuba and Yugoslavia could more readily provide armaments, expertise, and transport than many of the African states, most of which were critically short on the requisite material and logistical resources. Algerian diplomats facilitated introductions and served as translators (linguistically and culturally) for the Cubans. For example, Alphonse Massemba-Débat, president of the Republic of Congo (Brazzaville), told Jorge Serguera that the presence of an Algerian diplomat at his side vouched for Cuba’s revolutionary credentials.Footnote 23 Even if the sentiment was perhaps something of a diplomatic pleasantry, the fact is that geopolitically consequential relationships, crossing great distances, frequently resulted from brief and infrequent encounters such as these. Cuba was almost immediately assisting in the training of guerrilla fighters from numerous African territories, and probably also Palestine. In January 1965, the CIA reported the presence of Cuban officers at a camp in the mountainous Algerian region of Kabylia. The Algerians also assisted Che Guevara’s ill-fated mission to take a column of Cuban soldiers into Congo that year, although they did not think it advisable to participate directly in the struggles of other nations.Footnote 24 The Cuban role in Africa’s revolutions intensified in the early 1970s, culminating in the dispatch of thousands of soldiers to Angola in 1975, but the basis for that massive intervention was laid in the mid-1960s. Several small movements favored by the revolutionary network that the Algerians and Cubans participated in, such as the Angolan MPLA, Palestine’s Fateh, or the Zimbabwean African National Union (ZANU), later played central roles in their country’s politics.

But if these early years of Cuban-Algeria cooperation were testament to the potential and viability of Tricontinental solidarity, they also demystify the phenomenon. Indeed, the longer-term historical legacy of Cuban-Algerian cooperation is all the more remarkable for being based, in this initial stage, on scant apparatus or reciprocal knowledge. Guevara’s rash venture into Congo was the result of a simplistic, ideological reading of Africa from afar. Rapid decolonization after 1960 and the emergence of armed revolutions in South Africa and Angola convinced the inveterate Argentinian militant that the continent was in the throes of unstoppable revolutionary change that was itself part of a greater global story. In the same vein, Algerian analyses of Latin America in the early-mid 1960s often amounted to little more than rephrasing Cuban agitprop. The Algerian foreign ministry’s department for Asia and Latin America optimistically informed Bouteflika that “the revolutionary wind has blown strongly enough from Havana to have shaken up the situation in those countries where the United States’ grip is still very strong, and it threatens to substantially change things even more.”Footnote 25 At that time, the “department” for Asia and Latin America was meagerly staffed by people with little familiarity with either region. The section head, who had never visited Latin America, was delighted to be reappointed to the embassy in Bamako, Mali, in early 1965.Footnote 26 In comparison, a right-wing coup in Brazil in April 1964 put on hold Algerian plans to open a second embassy on the continent, after Havana, for narrow ideological reasons based on the Cuban perspective.

Still, despite the skepticism of many Western observers, leaders of both countries valued their relationship, in part for its ability to legitimize a diplomacy of revolutionary internationalism. Boumédiène’s overthrow of Ben Bella in 1965 temporarily put a damper on the alliance, as Castro and his colleagues initially assumed the coup had a counterrevolutionary character akin to that seen in Brazil. Kwame Nkrumah’s overthrow in Ghana the following February confirmed a pattern of early postcolonial regime changes. The Cuban government’s decision to put on the Tricontinental Conference therefore occurred in the context of – and partly in response to – the loss of several valued allies as well as systemic, worsening schisms within the global anti-imperialist milieu. A key goal of the conference was to reinforce and formalize the kinds of alliances Cuba and Algeria had been forming in the early 1960s in light of these worrying trends.

Schisms in the Global Anti-Imperialist Front

The 1966 Tricontinental Conference in Havana took place in the context of intense divisions within what could be thought of as the worldwide “anti-imperialist front” – that is, those Third World countries and communist countries that claimed that anti-imperialism was a core tenet of their international relations. From the founding of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) in Belgrade in September 1961 to the late 1960s, heated debate reigned over the nature, purpose, and organization of the Third World project. A moderate/radical divide emerged among the Afro-Asian countries, chiefly over how militant a position to take toward violent crises of decolonization such as the war in Algeria and the complex conflict that consumed Congo in late 1960. The Belgrade Conference did not constitute a simple and harmonious sequel to Bandung: it was largely an initiative of countries that took a more militant stance toward those two crises than the likes of India and the Colombo countries, and the Non-Aligned Movement in these years actually had a more provocative and subversive tenor than the neutralism celebrated at Bandung.Footnote 27 At the same time, certainly the greatest impediment to the Third World’s unity was the intensifying ideological and geopolitical rivalry between the USSR and the PRC. The Algerians and others saw competition between great powers as a boon for smaller countries, and the FLN had indeed already exploited Sino-Soviet tensions in the latter stages of their independence struggle. But after Belgrade, the Sino-Soviet split became a tedious obstacle even for those accustomed to profiting from such rivalries. China tried to squeeze its European rivals – the Soviets and Yugoslavs – out of the Third World coalition by emphasizing a more racially exclusive Afro-Asianism at the expense of a Non-Aligned Movement that the Chinese saw as a tool of the Yugoslavians and the Indians, the latter the primary antagonist in a fierce border dispute. As Nehru complained to Nasser regarding the extension of that territorial dispute into Third World affairs, “China’s main purpose seems to be disrupt the policy of non-alignment which has gained widespread support, not only among the Afro-Asian countries, but also from the Great Powers. I think our own conflict with China should be seen against this background.”Footnote 28

Therefore, when Cuba attended the Belgrade Conference in 1961, it entered a Third World coalition already beset by complicated, overlapping tensions. China pitted Afro-Asianism against the NAM; India defended the NAM against China but also feared that the NAM was dominated by those too eager to support guerrillas and insurgencies in places like Congo. At the same time, China also had the sympathy of many leading NAM participants because of its own aggressive stance on supporting violent revolutionary struggles, which compared favorably in their minds to the Soviet Union’s accommodating pursuit of “peaceful coexistence” with the West. As a further complication, some of the most militant Arab members of the NAM, notably Egypt and Algeria, worried that China’s racial definition of the Third World might distance them from the rest of Africa. Therefore, Cuba, Algeria, Egypt, and Yugoslavia shared a willingness to directly assist violent anti-imperialist struggles, mostly in Africa, and shared a desire to emphasize a more expansive, diverse, and inclusive sense of Third World solidarity. While visiting Belgrade in March 1964, Ben Bella told Tito that Algeria’s preference was to unite all “progressive forces” regardless of geographical, ideological, or racial distinctions, and the Yugoslav premier agreed wholeheartedly.Footnote 29

It was the emergence of this more assertive, revolutionary faction within the left wing of the Third World coalition that informed the articulation of Tricontinentalism. The proposal for a “Tricontinental Conference” issued from a January 1961 meeting of the Afro-Asian People’s Solidarity Organization (AAPSO), headquartered in Cairo. The organization had started out three years prior as a Soviet initiative to harness the evident energy of the Bandung movement. But by proposing in 1963 to host this Tricontinental event, the Cuban government was hoping to formally extend the Afro-Asian bloc into Latin America, to blur the lines between the NAM and the AAPSO, to diminish its own isolation in Latin America as much as strengthen its connections further afield, and to reinforce its credentials as an autonomous Third World actor rather than a Soviet satellite. Indeed, regarding the final consideration, the Soviets initially preferred that Brazil host the Tricontinental – before the right-wing coup there in 1964.Footnote 30

The Cuban desire to host the Tricontinental Conference reflected smaller and medium-sized countries’ efforts to institutionalize Third Worldism in the face of the bigger powers’ disruptive feuds. Yugoslavia and Egypt had mostly driven the founding of the NAM, despite Indian and, especially, Chinese and Soviet wariness of the project. While the Bandung Conference had been the product of a short-lived understanding between the two giants of Asia – India and China – Yugoslavian publicity material happily described the Belgrade summit as “a conference of small and medium-sized countries.”Footnote 31 In that spirit, the likes of Algeria (still a liberation movement in 1961), Cuba, and Ghana enthusiastically came on board. Likewise, Nasser’s government hosted a succession of Third World-related meetings after Belgrade – AAPSO meetings, non-aligned meetings, and the second summit of the Organization of African Unity in 1964. At the same time the Cubans were bidding to host the Tricontinental, the Algerians proposed, successfully, to hold the second Afro-Asian heads of state summit, or “Bandung II,” in 1965. Smaller countries saw the institutionalization of solidarity as a means to magnify their influence, especially if they achieved even greater prominence (and a real, though limited degree of influence over the agenda) by hosting major meetings and permanent secretariats. On the other hand, by dint of their sheer size, India, China, and the Soviet Union had little need of institutions that they could not closely control, with perhaps their ideal example being the interwar-era Communist International, or Comintern, through which Moscow had dominated communist parties worldwide. As a result, one constant dynamic of Third Worldist diplomacy in the 1960s was the tension between smaller organizing powers and the feuding major powers that wanted to weaponize organizing themes and institutions against one another.

The Sino-Soviet split, and related intra-communist schisms, damaged the vitality of AAPSO badly, even fatally. The animosity between Moscow and Beijing spilled out into the open in dramatic fashion at AAPSO meetings in Moshi, Tanganyika, in February 1963 and Algiers in March 1964.Footnote 32 Chinese and Soviet delegates belligerently strove to assert their ideological supremacy over one another while also competing, somewhat paradoxically, for the loyalty and support of the attending Third World governments, who were for the most part disinterested in and perplexed by the jargon-laden vitriol the communist delegates subjected them to. As one African attendee of the Algiers meeting memorably groused,

[M]ost of us haven’t read a line of “The Capital.” So what interest have we in your doctrinaire quarrels? I have had enough of this situation where whenever I eat my sandwich, I am accosted by someone who wants to know my opinion on the Soviet stand, and when I drink my coffee, by someone who asks me about the Chinese arguments. I want to be able to eat in peace!Footnote 33

If the Chinese scored points by criticizing the Soviet espousal of peaceful coexistence – which the Algerians, Yugoslavs, and Cubans, among others, suspected meant Moscow’s conceding that Latin America was in the United States’ “sphere of influence” and parts of Africa in Britain and France’s – they also suffered from the increasingly off-putting, indecorous intensity of their attacks.Footnote 34 Other members of the anti-imperialist world now regularly complained of the “doctrinaire states,” seeing them as losing their credibility as revolutionary vanguards through their preoccupation with insular arguments, even if the Soviet Union and China remained necessary allies for many developing countries. Indeed, general enthusiasm for AAPSO waned: after a discordant meeting in Ghana in 1965, the next one did not take place until 1972. Seeing opportunity in crisis, the Cuban government founded the Organization of Solidarity with the Peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America (OSPAAAL) at the 1966 Tricontinental meeting as a substitute for the foundering AAPSO.Footnote 35 However, the association with AAPSO helped limit the new organization’s appeal, for the most part, to those nations that openly identified with communism, especially in its Maoist, peasant-oriented form. This lean to the left would become a defining element of revolutionary Tricontinentalism, eventually driving a wedge in the broad solidarity envisioned by Algerian ambitions for the Third World project.

Additionally, the Chinese government’s willingness to use racial tensions against its Soviet and Yugoslavian rivals strained ambitions for an expanded Third World unity. The Chinese argument, expressed bluntly by officials and in propaganda material that primarily targeted sub-Saharan Africa, was that white Europeans like the Russians and Yugoslavs were simply not part of Asia and Africa. Moreover, questions of basic racial-geographic eligibility aside, Beijing argued that by dint of their mentality and experiences, white countries simply could not relate to or understand the problems of the non-Western world. “[W]hen we talk to you,” Mao Zedong told Africans, “there is no feeling that I bully you or you bully me, nobody has a superiority complex, we are both of a colored race.”Footnote 36 Showing their fear of China’s racial arguments, a Soviet official fretted that Africans “now relate to all whites with suspicion,” while Tito railed against the notion that “all blacks are good and all whites bad.”Footnote 37

This racial line of attack within the communist world’s schism was especially worrying for some of the most enthusiastic participants in the Third World scene, above all the militant wing that included Algeria, Egypt, Yugoslavia, and Cuba. Each of those four countries was a prime mover in the Non-Aligned Movement as well as the transnational network of support for liberation movements and armed revolutionary groups. The latter activity was especially focused on Central and Southern Africa in this period, given the continued existence of Portuguese colonialism and other forms of white minority rule in South Africa and Rhodesia. The racial question also bore directly on the ongoing crisis in Congo-Léopoldville, which was one of the most pressing concerns for the NAM. Moishe Tshombe, the Western-backed leader of Congo who was loathed by the militant countries, strikingly protested against Algerian and Egyptian support for the rebels in his country by staging a reenactment of Arab slave raids in the main football stadium in Léopoldville (Kinshasa).Footnote 38 So, as Che Guevara prepared to lead a Cuban column into Congo in 1965, Nasser warned that he might appear like “another Tarzan … a white man coming among black men, leading them and protecting them.”Footnote 39 It was a revealing indication of how leading the international revolutionary vanguard could resemble a new sort of imperialist civilizing mission.Footnote 40

China’s rather brutal willingness to sow division on such profound lines also informed the Algerian and Cuban approaches to the two upcoming Third World meetings that were so important to them both: Bandung II in Algiers in 1965 and the Tricontinental in Havana in January 1966. The leaders of both countries sought to subsume the racialism that threatened to emerge from either cultural or geographic delineations of an Afro-Asian alliance within a secular, revolutionary solidarity that stretched across the Atlantic. They, as well as like-minded allies, advocated inclusive programmatic and political criteria for admission to the worldwide anti-imperial coalition. Ben Bella conceded to Tito that “we [Algerians] are white like you, maybe a little more brown,” and agreed with the Yugoslav’s contention that “the wrongheaded idea of divisions according to race merits the [Non-Aligned states’] strongest censure.”Footnote 41 Ben Bella’s government favored including the Soviet Union in Bandung II and also desired expanding the NAM and the Afro-Asian group to include Latin America and beyond. Ben Bella told Tito that he desired “an enlargement of the circle of nonaligned states … [I]n addition to Asian countries, Latin American and European countries … [should] participate in the conference too. We also think that ideas about continents and skin color need to be overcome because progressive forces exist all around the world.”Footnote 42 At the heart of this emerging ideology was an attempt to renegotiate historic inequalities between Global North and South, as well as countries great and small, by mobilizing a broad political coalition across all continents.

In the end, schisms within the Third World might well have ruined Bandung II, even if Boumédiène and Bouteflika had not chosen to overthrow Ben Bella on the eve of the conference in June 1965. China fought tooth and nail to prevent the Soviets from attending, while many African countries were inclined to stay away because the war of rhetoric between the communist countries gave rise to increasingly polarizing discourse. Boumédiène and his associates had removed Ben Bella from power before Bandung II took place because they feared, if the conference were successful, his augmented power and prestige would render him untouchable. The timing of the coup reflects how important postcolonial diplomacy was in bestowing political legitimacy: if hosting the conference might have made Ben Bella untouchable, those who deposed him likewise hoped that their hosting the conference instead might confirm and secure their assumption of power. Accordingly, the new government in Algiers attempted to hold the postponed conference a few months later, in November 1965, in order to enjoy the legitimization of the Third World. But China’s disputes with the Soviet Union and with India, as well as the seeming loss of its Indonesian ally due to anti-communist massacres there, induced Beijing to successfully obstruct multilateral efforts to keep Bandung II alive.Footnote 43 In the skeptical view of the Indian delegation, China belatedly discovered “that Asian and African countries had a mind and will of their own … As the Conference could not be bent to its will, China set about scuttling it.”Footnote 44 As a meaningful organizing theme in Third World affairs, Afro-Asianism effectively died in Algiers in June 1965.

The same vicious factionalism greatly limited Cuba’s success in ensuring that the expanded theme of Tricontinentalism might provide a genuine successor to Bandung. In many respects, the January 1966 Tricontinental Conference was a less ambitious and more narrow-minded event than the canceled Algiers conference had been intended to be. Castro’s firm embrace of communism and the conference’s origins in AAPSO, an organization created in order that Moscow might capture the energy of Afro-Asianism, meant the Tricontinental became a distinctly ideological event. Though it assembled representatives from all continents including both Europe and North America, the 612 delegates came mostly from communist parties or avowedly leftist organizations, including political parties, unions, liberation movements, and the like. An emphasis on militant, armed revolutions became a central component of the emerging philosophy guiding the conference. This characteristic alienated old guard Third Worldists even as it provided a platform for socialists such as Amílcar Cabral, the revolutionary nationalist from Portuguese Guinea who came to Havana in search of military and diplomatic support.Footnote 45 Communist infighting naturally influenced the proceedings greatly; the Soviets and Chinese fought over the invitation list beforehand, each trying to stack the crowd in its favor. At Chinese insistence, Yugoslavia was excluded, though the Egyptians subsequently facilitated the attendance of a Yugoslavian delegation with “observer” status, which was a particularly inconsequential achievement at a nongovernmental conference.Footnote 46

All told, the Tricontinental’s efforts to expand the geography of anti-colonial revolution met severe challenges. Chinese objections greatly limited the actual participation of sympathetic Latin American movements, since these tended to be pro-Soviet rather than pro-Chinese. For the same reason, China opposed Cuba’s proposal to institutionalize the Tricontinental by creating a new secretariat in Havana in the form of OSPAAAL. In this China failed but, in time, the influence of the new OSPAAAL would prove to be curtailed by more prosaic regional rivalries. Egypt was loath to see AAPSO, headquartered in Cairo, supplanted altogether. Many African attendees were also wary of Afro-Asianism acquiring too heavy a Latin American focus. The conference’s emphatic emphasis on denouncing Yanqui imperialism in the strongest terms, with only cursory reference to European colonialism, encouraged their fears. The observing Indian chargé d’affaires concluded that,

If the Conference succeeded in creating a permanent secretariat in Havana, it created a house divided in itself, whose effectiveness and the wisdom itself of the choice of … site was contested from the very start by the builders themselves. It will now be lived in by triumphant Latin Americans, disgruntled Africans, the warring partisans of the Soviet and Chinese camps, apart from the gullible many who are likely to be stampeded into submission in the Sino-Soviet war of nerves!Footnote 47

His analysis was itself an example of schism within the Third World, with Indian diplomacy eager to see Chinese ambitions foiled and the influence of militant revolutionary factions curtailed. In that respect, his report is doubly proof of the roiling rivalries within the anti-colonial solidarity movement, a mere decade after Bandung.

Conclusion

In the 1960s, the similarity of views and closeness of cooperation between Algeria and Cuba led many to equate the two revolutionary countries. Indeed, it was common for senior Algerian cadres themselves to describe their country as the “Cuba of the Maghreb” or even the “Cuba of Africa.” The Soviet Union’s increased economic and military assistance to Algeria reflected the hope, at least in Khrushchev’s time, that it would follow the Caribbean country’s political progression toward a full commitment to “scientific socialism.” Such close association of the two countries concerned some sympathizers, such as the Yugoslavian ambassador in Algiers who fretted that “[t]he importance that the USSR wants to give to the Algeria-Cuba analogy has dubious value … [because] the West and the reactionaries [will] use and amplify [it] in order to isolate Algeria.”Footnote 48 His fears were well founded. However, rather than economic and ideological concerns, it was Algeria and Cuba’s collaborative support for armed revolutionary movements that most displeased Washington. After all, there was no consensus in the Third World on openly supporting and abetting violent movements. The American official in charge of Algerian affairs admitted to a British colleague that “[t]he further up the State Department hierarchy you go, the more you hear the view that [Ben Bella] is ‘no better than Castro’.”Footnote 49 Kennedy had not wanted to concede Algeria to the Eastern bloc altogether, but by 1965, Algerian-Cuban cooperation in fomenting revolution in Latin America and Congo led many American national security officials to categorize Algeria as a hostile entity.

Nevertheless, the Cuban and Algerian positions in Third World affairs started to diverge somewhat in the second half of the 1960s. In part, this divergence was diplomatic fallout from the coup against Ben Bella, to which Castro initially reacted furiously. Assuming, as many did, that the military-orchestrated coup was a rightist counterrevolutionary development, Castro publicly warned that “events in Algeria affect us all, [Boumédiène and the coup’s other instigators] have harmed the revolutionary movement in Africa and in all the world.”Footnote 50 But the more fundamental cause of the growing distance between Algeria and Cuba was the fact that the former was more invested in the established structures and norms of the international order, while Cuba continued to act in more provocative, insurrectionary ways. Algeria continued to aid revolutionary movements opposed to colonial and minority regimes much of the world viewed as illegitimate, especially in Southern Africa and Palestine, but in the late 1960s, Algiers increasingly focused more on diplomatic approaches to addressing systemic economic inequalities. The presence of some Black Panthers in Algiers at the end of the decade attracted a lot of attention in the United States, but in practice the Algerian authorities were becoming more selective in their support for revolutionaries: they were increasingly skeptical of the Panthers’ seriousness and secretly irritated that Algiers had become a destination of choice for hijackers.Footnote 51 As one of Algeria’s senior diplomats explained to his colleagues in 1965, “Today, [the new nations’] essential goal is [to] gain access to the international responsibilities at the heart of the United Nations, and to make sure that their interests and economic imperatives are no longer subject to the whim of a few great powers.”Footnote 52 There was no open schism between the two allies, who continued to collaborate on numerous issues, but Algeria began to place greater emphasis on broader-based Third Worldist cooperation, especially in the economic realm, and showed greater respect for the principle of noninterference in other developing countries’ internal political affairs.

The January 1966 Tricontinental Conference, therefore, ran somewhat against the prevailing current of the Third World’s general progression to more peaceful, more inclusive, and more economically oriented modes of collaborative mobilization. The UNCTAD and G-77 groups featured strong Latin American representation from the outset, not least in their intellectual and organizational apparatus, so the majority of the continent’s governments voted for the initial exclusion of Cuba from these new entities, just as they also voted to expel it from the OAS around this time. Consequently, Cuba riposted by using the Tricontinental as an opportunity to promote a narrower and ideologically purer form of solidarity. Many of the Latin American delegates at the Havana Conference, being representatives of communist parties and other opposition groups, kept their identities secret. Unlike the core Afro-Asian, Non-Aligned, UNCTAD, or G-77 events, the Tricontinental was a nongovernmental, nonofficial gathering. Key Third World countries like India and Algeria were represented by ambiguously titled, nongovernmental entities such as the Algerian Committee for Afro-Asian Solidarity. The latter included at least one senior diplomat but kept an uncharacteristically low profile.Footnote 53 Western officials were not far off in portraying the Tricontinental as a communist gathering, for the event did have an overwhelmingly communist and like-minded fellow-traveling constituency. Prior to his abduction and assassination, Ben Barka himself had said that the conference “would blend the two great currents of world revolution: that which was born in 1917 with the Russian Revolution, and that which represents the anti-imperialist and national liberation movements of today.”Footnote 54 Full-forced revolutionary resistance against Yanqui imperialism was the central theme of the Tricontinental’s discourse, with Guevara’s memorably blood-curdling appeal to create “many Vietnams” representative of the tenor of proceedings.Footnote 55

In contrast, the first G-77 ministerial meeting, held in Algiers in October 1967, gave Boumédiène’s government the opportunity to position itself as a prime mover in the more consensual, legalistic, and institutional campaign to reform global economic structures that was quickly growing to encompass practically all the governments of the developing world. Though the G-77 group of developing countries had been formed at the first UNCTAD in 1964, it developed a permanent institutional structure at the first ministerial meeting, and Algeria’s profile clearly benefited from the G-77’s founding statement of principles being known officially as the “Charter of Algiers.” This set out a program of action (including commodity cartels, price controls, and trade liberalization) that became the basis for the agenda of the New International Economic Order in the 1970s.Footnote 56 With its significant deposits of natural gas and oil, Algeria possessed commodities of significant value that were already the subject of intense political and intellectual scrutiny, and the North African country was thereby much better integrated into the mainstream of economic life in the Global South than its Cuban ally was.Footnote 57 The architect of Algeria’s development project and hydrocarbon nationalization plans, Minister of Industry and Energy Belaïd Abdesselam, presented Algeria’s critique of the global economic system at the 1967 meeting, and thereby exerted great influence over the content of the Charter of Algiers.Footnote 58 Perhaps no country boasted greater influence over the Global South’s economic diplomacy over the next decade. Additionally, hydrocarbons bestowed Algeria with significant revenues to plow into its modernization drive, giving the country the appearance of genuine postcolonial socialist prosperity in the 1970s. It was on this basis that the peripatetic Polish appraiser of post-coloniality, Ryszard Kapuściński, described it as “the pivotal Third World State … a model, bright and entrancing.”Footnote 59

Together, the 1966 Tricontinental Conference in Havana and the 1967 G-77 meeting in Algiers set the course for international affairs in the Third World over the remainder of the Cold War. On the one hand, the Algiers Charter facilitated the construction of what became known in due time as the Global South: an assemblage of practically all developing countries, defined by inegalitarian global economic structures and the disparity in material prosperity between North and South. Conventional wisdom holds that the NIEO and UNCTAD projects ultimately failed, being blown apart by debt, structural adjustment, and neoliberal capitalist globalization in the 1980s and 1990s.Footnote 60 Yet the G-77’s agenda still exerts influence, helping to stymie the most recent round of World Trade negotiations and informing the design of the Paris climate change treaty. In comparison, the Tricontinental’s communist-led call for global insurgency was becoming more of a radical niche within the Third World movement, even in the late 1960s. Certain lingering anti-colonial struggles continued to command the sympathy of most of the Southern Hemisphere – South Africa, Palestine, and so on – but national political elites were also increasingly concerned that the controversy that inevitably accompanied armed struggle would jeopardize the greater cause of reforming global economic structures. Perhaps no event better encapsulates this divergence within the Third World than the terrorist attack on the OPEC headquarters in Vienna in December 1975: a small group of international terrorists, led by the notorious Venezuelan Ilich Ramírez Sánchez (“Carlos the Jackal”), took representatives of OPEC hostage in order to call attention to the Palestinian cause. The event demonstrated revolutionary anti-colonialists’ frustration with the new postcolonial establishment.Footnote 61

The Tricontinental agenda did leave a deep and lasting legacy, though perhaps one felt mostly in specific localities. Because of the Tricontinental’s influence and the reduced participation of other postcolonial countries in violent causes, many of the major national liberation struggles of the 1970s and 1980s, such as those in Portugal’s African colonies and Palestine, took on a more communist character than their predecessors elsewhere in Africa and Asia.Footnote 62 But the Tricontinental’s undisguised purpose of confronting the United States also helped ensure that events in places such as Angola, Mozambique, and Palestine took a tragic and bloody turn, entailing decades of civil war and unresolved political impasses. For a time, Guevara’s uncompromising vision of many Vietnams came to pass. But by the 1990s, the end of the socialist road was also accompanied by a decisive turn away from violent anti-colonialism. In Northern Ireland, Palestine, and South Africa, among other places, nationalist revolutionaries renounced both armed resistance and socialism. In that sense, Tricontinentalism and the Third World’s vision of global economic transformation both shared the same fate.Footnote 63