For US policymakers, the Havana Tricontinental Conference of January 1966 took place at a time of both confidence and vulnerability in US relations with the Third World. In the second half of 1965, the Lyndon B. Johnson administration believed that the prevailing winds in the Third World were blowing in its favor. The collapse of the “Second Bandung” African-Asian Conference at Algiers between June and October, the military coups against Algerian leader Ahmed Ben Bella and Indonesian leader Sukarno, and the collapse of the Chinese push for leadership of the Afro-Asian movement were all seen in Washington as a validation of US foreign policy and as heavy blows to several key antagonists. These perceived victories notwithstanding, however, US policymakers remained aware of the general unpopularity in much of the Third World of Washington’s perceived support for European and white settler colonialism in Asia and Africa, of the US role in global capitalism, and of the recent US interventions (overt and covert) in Cuba, the Congo, the Dominican Republic, and above all, Vietnam.Footnote 1

Unlike the Algiers conference, which was to have been a meeting of national governments across the political spectrum and including many Commonwealth and other governments broadly sympathetic to US and Western interests, the explicitly socialist and anti-imperialist Tricontinental Conference would include no voices friendly to Washington and offered no channel through which the United States might influence the conference preparations or outcome. The Tricontinental’s institutional predecessor, the Afro-Asian People’s Solidarity Organization (AAPSO), was technically a nongovernmental organization; delegates participated on behalf of national Solidarity Committees, umbrella organizations of mostly socialist and communist groups and/or liberation movements. Some of these groups worked with the blessings of their national governments, but others stood in opposition to regimes with ties to the United States. Launched at Cairo in 1957 and sponsored by the Soviet, Chinese, and Egyptian governments, AAPSO had articulated an increasingly militant and revolutionary message at a series of conferences over the ensuing decade.Footnote 2

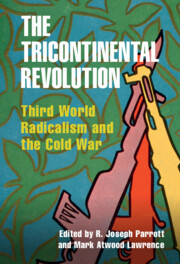

Figure 8.1 Tricontinental iconography highlighted imperial violence, offered satiric takes on Western icons like Uncle Sam, celebrated Global South cultures, and championed militancy. Their powerful simplicity mixed clear calls to action with historic references and inferred inequalities that continue to animate anti-imperial politics. OSPAAAL, Asela Perez 1970. Screen print, 53x33 cm.

The Tricontinental Conference aimed to extend AAPSO into the United States’ backyard through the inclusion of Latin American communist parties and guerrilla movements. The conference was to be the largest gathering of self-identified revolutionaries in world history and portended nothing but hostility to US interests. Furthermore, the conference’s host, Washington’s nemesis Fidel Castro, was the very embodiment of left-wing revolutionary defiance of the United States, having already survived almost a decade of efforts first to prevent him from taking power during his guerrilla war of 1956–58 and then to undermine, isolate, and overthrow his revolutionary government only ninety miles from US shores.Footnote 3

By defining the nature of the Tricontinental Conference agenda and invitees as they did, the organizers left few if any avenues for the United States to influence the preparations for or course of the conference through allied or sympathetic delegates. Washington’s lack of leverage stands in contrast to successive US governments’ efforts to shape the course of other Third World internationalist conferences from Bandung in 1955 through the non-aligned conferences at Belgrade in 1961 and Cairo in 1964 and the abortive “Bandung II” at Algiers in 1965. As several historians have shown, US diplomats played active roles behind the scenes before and often during each of these conferences. In general, these efforts followed a pattern. In advance of each conference, US officials viewed the prospective gathering as a threat with the potential to bring together anti-white, anti-Western, anti-imperialist, and anti-capitalist currents hostile to the United States and its allies. Washington feared that its most ardent antagonists in the Third World – above all the People’s Republic of China but also at times Castro’s Cuba, Ben Bella of Algeria, Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, and Indonesia’s Sukarno – would use the conference to try to unite the Third World behind a radical agenda inimical to US interests and turn it into a forum for propaganda and denunciation of the United States and its allies.

After considering, but discarding, the feasibility and desirability of trying to prevent the conferences from ever taking place by discouraging participation by governments sympathetic to US views, officials adopted (to varying degrees) a strategy of engagement with each conference to try to moderate its tone and outcome by ensuring that pro-Washington and pro-Western delegations attended and made their voices heard. US diplomats worked with and through sympathetic governments to shape the roster of invitees, the agenda and rules of procedure, and the tone of the eventual resolutions and declarations in order to minimize criticism of the United States and its allies, albeit with varying degrees of vigor and success. In the aftermath of each conference, US officials expressed relief that, from their point of view, things could have been worse. Washington was particularly sanguine in late 1965 given the fallout from the aborted Bandung II at Algiers; Johnson administration officials believed that their subtle but vigorous, behind-the-scenes diplomatic efforts to thwart the Sino-Indonesian push to radicalize Third World internationalism had been effective. “Moderate” and pro-US voices in the Third World had prevailed over the militant Afro-Asian left wing led by Beijing and Jakarta.Footnote 4

The actions of the Johnson administration in response to the Tricontinental Conference would be largely consistent with the pattern set at these previous conferences. The Tricontinental presented the US government with both a revolutionary threat and a counterrevolutionary opportunity, and Washington responded with another vigorous but largely behind-the-scenes diplomatic effort to meet the challenge and exploit the opportunities it presented. The core of this strategy was to exploit the political and ideological divisions among the movements represented at Havana, largely indirectly and by proxy, in order to undermine the Tricontinental solidarity movement and isolate and harass Washington’s enemies. While US officials considered their counteroffensive to be largely successful in short-term diplomatic and material terms, the push for Tricontinental revolutionary solidarity nevertheless highlighted the long-term challenges that Washington faced in seeking to suppress liberation movements across the Third World.

Anticipating Conflict

Infighting along ideological, methodological, and regional lines had plagued AAPSO, and Third World revolutionary internationalism more broadly, ever since the late 1950s. At the heart of this struggle was the Sino-Soviet contest for leadership of the global revolution. The gradualist strategy of “peaceful coexistence,” economic competition with the capitalist West, and the gradual achievement of socialism practiced by Moscow and the orthodox communist parties of Europe and Latin America conflicted with the more confrontational line of revolutionary armed struggle and militant anti-imperialism advocated by China, Maoist-inspired movements in Asia and Africa, and Fidel Castro and Che Guevara in Latin America.Footnote 5

The potential for discord increased with the projection of AAPSO and ideological competition into Latin America. The Latin American Left in the 1960s was being simultaneously reinvigorated and fragmented by the victory of the Cuban Revolution and the export of Castro and Guevara’s program of guerrilla warfare and revolutionary confrontation to the continent. The region’s established orthodox communist parties continued to adhere to Moscow’s gradualism but were challenged by new or splinter factions favoring direct guerrilla confrontation as advocated by Havana and Beijing. In a few cases, these more confrontational groups received material and ideological support from Havana. The deepening divisions prompted the Soviets and Cubans to convene a secret summit of Latin American communist parties in Havana in November 1964. Castro pledged to cease his rhetorical attacks against the orthodox parties, while Havana and Moscow pledged to increase their own support for the liberation struggle. The Tricontinental Conference would mark the culmination of these internal tensions and the efforts to overcome them within the Latin American and world communist movements, as the Cuban government continued its efforts to build and radicalize a coalition that united Second and Third World governments and nonstate movements behind a militant revolutionary program.Footnote 6 It also came amid the period of most severe diplomatic and economic isolation for Cuba in the hemisphere, following its recent suspension from the Organization of American States (OAS), the imposition of an OAS-wide economic embargo, and the rupture of diplomatic relations between Havana and all the governments of the hemisphere save Canada and Mexico. It came, too, at a time when the Cuban government – economically dependent on the Soviet Union but ideologically more compatible with the Chinese and eager to see like-minded movements come to power in the hemisphere – found its balancing act between the two communist giants increasingly difficult.Footnote 7

In response to the public revelation of the November 1964 Havana communist summit, US policymakers anticipated an increase in insurgent activity in the hemisphere, as Moscow sought to blunt Chinese and Cuban criticism and reassert its leadership of world revolution by more tangibly backing Latin American guerrillas.Footnote 8 The CIA predicted that Castro “personally attaches great importance” to the Tricontinental Conference and intended to use it to assert leadership among Third World liberation movements and ameliorate Cuba’s diplomatic and economic isolation.Footnote 9 The Agency also predicted that “fireworks resulting from the Sino-Soviet dispute may well seriously disrupt the conference,” but that it would nonetheless offer “a ringing indictment” of US policies.Footnote 10

Washington had monitored the effort in spring 1965 – spearheaded by Castro’s government in cooperation with its closest Third World ally, Ben Bella’s Algeria – to overcome the Sino-Soviet and other rivalries within AAPSO in order to proceed with the process of convening a tricontinental solidarity conference in Havana.Footnote 11 After the Johnson administration intervened in the Dominican Republic, Secretary of State Dean Rusk acknowledged in a cable to embassies in Latin America in early May that the “situation obviously provides exceptional springboard for conference propaganda on colonialism and imperialism, and most timely for AAPSO objective of extending its activities and influence in Latin America.”Footnote 12 Rusk instructed diplomats in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, meanwhile, “to expose this meeting for what it really is and whom it actually represents,” that is, the most extreme and dangerous elements of their countries’ political milieu. While “informal discussions” with local officials and other opinion leaders could be useful in this effort, Rusk instructed that this task should be carried out “preferably where possible through unattributable items in local media,” in order to reach a broader public.Footnote 13

The perceived gains from the Bandung II debacle at Algiers and the other critical Afro-Asian developments in the second half of 1965 do not seem to have fundamentally altered the US views of or approach to the impending Tricontinental. In December 1965, Undersecretary of State George Ball cabled all US embassies to instruct them to communicate with their host governments in order to expose the conference “for what it really is and whom it actually represents,” while at the same time to “avoid building up or stimulating [public] interest in the Conference.” Explaining these instructions, the cable predicted that, “The conference will be an anti-West, particularly anti-U.S., propaganda forum” that would denounce Washington for its support of reactionary governments in Rhodesia and the Congo, its embargo against Cuba, its escalating war in Vietnam and recent occupation of the Dominican Republic, and its “racial problems” at home. While Castro was expected to project his own leadership of the Third World and the Latin American Left, the Soviets would seek to do the same, outflanking the Chinese in the process. Beijing, meanwhile, was expected to try to block the proposed merger of AAPSO into a single Tricontinental organization, since the addition of the pro-Moscow Latin American communist parties would dilute Chinese influence in the Afro-Asian bloc.Footnote 14 Therefore, before the conference began, Washington, while acknowledging its own vulnerabilities, had spotted potential weaknesses in the incipient Tricontinental movement and begun to foment opposition.

“Noise” and “Practical Results”

In its critique of the geopolitical situation, the conference played out much as US observers predicted.Footnote 15 While celebrating that formal colonialism had retreated from most of Asia, the Middle East, and Africa, the conference called for the overthrow of the remaining Portuguese, British, and French colonies and of the white settler regimes in South Africa, Rhodesia, and Israel. The conference also denounced the turn to neocolonial economic exploitation and political control of Third World peoples through “reactionary” client governments and militaries in countries such as Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, Guatemala, the Congo, and Thailand.Footnote 16

While denouncing European colonialists, white settlers, and local collaborators, the Tricontinental aimed its main critique at the United States. Surprising the US National Security Council staff with his militancy, Cuban President Osvaldo Dorticós told the assembled delegates in his welcoming speech that, “U.S. imperialism, the center of world reaction and the foremost enemy of peace and progress, unscrupulously carries out within the framework of a perfectly defined world strategy, any number of openly criminal actions.” Washington, he said, funded and trained counterinsurgency forces; sustained Portuguese, South African, and Israeli colonialism; continued its efforts to overthrow the Cuban Revolution; and intervened militarily in Vietnam and the Dominican Republic.Footnote 17 Accordingly, the Conference’s General Declaration proclaimed: “To destroy the domination of Yankee imperialism is an imperative issue for the complete and definitive victory of the anti-imperialist struggle in the three continents, and all efforts of the peoples should converge toward this aim.”Footnote 18

Caught up in the revolutionary spirit and pressured by militant hard-liners, the Tricontinental delegates declared that globally coordinated armed struggle was the primary means to defeat Yankee imperialism. The militants prevailed in a hotly contested “Resolution on Peaceful Coexistence,” which restricted this concept of relations between socialist and capitalist states, denied that coexistence was possible between imperialists and their victims or between the working and capitalist classes, and upheld the right of oppressed peoples to fight against their oppressors and to receive aid from others in their struggle.Footnote 19 The vote represented a victory for advocates of militant revolution such as the Cuban hosts and the Maoists, who rejected the gradualist Soviet vision of international revolution and favored instead a newly assertive brand that combined traditional Marxist readings of class warfare with a specifically Third World anti-imperialism. Pushing this more assertive reading of international revolution, Castro closed the conference with a two-hour speech in which he argued, “sooner or later all, or nearly all, of the peoples will have to fight, arms in hand, for their liberation.”Footnote 20 The CIA called it Castro’s “most explicit call for armed revolution” since his 1964 modus vivendi with the pro-Soviet parties and warned of “renewed Cuban interest in insurgent activities throughout the hemisphere.”Footnote 21

The State Department noted the increasing theoretical divergence between the more measured revolutionary approach of the Soviet Union and the more aggressive rhetoric of Third World anti-imperialists led by Cuba and China. But in the words of a cable from Undersecretary Ball, the department saw this rhetorical battle mostly as “noise.” Washington’s focus moving forward was on the potential “practical results” of the Havana conference that could tangibly threaten US interests.Footnote 22 These included the creation of a Committee of Assistance and Aid to the National Liberation Movements – tasked with providing “moral, political, and material aid” to world revolutionaries – and a Tricontinental Committee for the Support of the Vietnamese People.Footnote 23 The twenty-seven Latin American delegations moved to support revolution in the hemisphere by creating a Latin American Solidarity Organization (Organización Latinoamericana de Solidaridad, OLAS), headquartered in Havana, to hold its inaugural meeting in 1967.Footnote 24 The new OSPAAAL secretariat, to be constituted in Havana, was to coordinate all these revolutionary efforts on a global scale and prepare for a Second Tricontinental Conference in Cairo in 1968.Footnote 25

From Washington’s point of view, however, the most important practical outcome of the conference was its demonstration of the deepening fissures in the socialist world. Ball perceived the “Sino-Soviet dispute visible in all proceedings” and noted that the “speeches by Soviet and Chinese delegates, as well as respective allies, [were] loaded with barbs and recriminations as two big powers struggled for domination.” Many African and Arab delegations, meanwhile, were upset at the perceived neglect of their interests, according to the Department’s intelligence reports.Footnote 26

A Global Counteroffensive

In response to the Tricontinental Conference, the US State Department launched a sophisticated and ultimately successful diplomatic effort to exacerbate those same divisions in order to discredit, divide, and undermine the Tricontinental project around the world. For the State Department, the Tricontinental Conference was as much a counterrevolutionary opportunity as a revolutionary threat. As recounted in the department’s internal history of the period, and confirmed in the archival record, this counterrevolutionary effort had three main objectives. First, the Department endeavored to arouse anger in Latin America and the rest of the “Free World” in order to use the Tricontinental as a pretext for deepening Cuba’s diplomatic and economic isolation, on the basis that Havana aspired to become a revolutionary base that could threaten noncommunist governments everywhere. Second and more successful was the effort to peel the Egyptian regime off from the Tricontinental coalition and abort the Second Tricontinental Conference scheduled for Cairo in 1968. Third, the principal and most elaborate effort was to use the OAS and United Nations (UN) as international fora to denounce the Tricontinental and exert diplomatic pressure on the Soviets. “The US basic tactic” in all of these efforts, the internal history states, “was to remain in the background and say little publicly, while quietly stimulating Latin American and other criticism and action against communist sponsors and participants. … [I]t was particularly important to make certain that Latin American protests appeared as totally spontaneous, rather than as arranged or prompted by us.”Footnote 27 Adopting these goals and tactics, ironically, the US government essentially conformed to the Tricontinental’s depiction of US foreign policy as neocolonial and counterrevolutionary.

On January 21, 1966, as delegates made their way home from Havana (often clandestinely via third countries), Secretary Rusk cabled US embassies in Latin America, instructing them to suggest that their host governments put pressure on West European and Japanese governments to conform to the OAS embargo and curtail their trade with Cuba. The Tricontinental, they were to argue, highlighted the “basic inconsistency” between “free world” countries’ trade and development programs in Latin America and their simultaneous trade with Cuba, which was indirectly funding the “disruption” of those same Latin American countries. United States diplomats were to suggest that Latin Americans pressure the Free World’s holdouts to purchase sugar from other sources and to deny Cuba access to credit and agricultural, transport, and communications equipment.Footnote 28 Rusk followed up individually with embassies in Guatemala City and Lima.Footnote 29 The absence of subsequent documentation suggests that this initiative did not amount to much, but the intent is indicative of the US effort to use the Tricontinental to further isolate and impoverish Castro’s Cuba.

More sustained and successful was State’s effort to drive a wedge between the Egyptian government and the rest of the solidarity movement. The AAPSO had been founded and headquartered in Cairo, and AAPSO Secretary-General Yusuf al-Siba’i had ties to the Egyptian regime of Gamal Abdul Nasser. Nasser’s government, however, had grown increasingly disillusioned with AAPSO as Marxist sectarianism and Sino-Soviet infighting came to dominate the organization.Footnote 30 Egyptian discomfort deepened when the solidarity project’s extension to Latin America threatened governments with which Nasser maintained friendly relations. The US ambassador in Cairo, seeing Egypt “reconsidering” its support for the movement, met with several Latin American diplomats in Cairo and “suggested timely representations might encourage this promising development.”Footnote 31 Agreeing with the Colombian Foreign Minister’s determination that “Nasser should be made to eat crow in some way” for his role in supporting Cuba and regional leftist movements, Undersecretary Ball instructed all Latin American posts to facilitate confrontation between their host governments and the Egyptians, while taking care to “avoid impression US taking initiative.”Footnote 32 Ball believed that “stern LA reaction would serve as salutary lesson to such chronic meddlers as Nasser and Nkrumah that they cannot with impunity support commie inspired intervention in LA or elsewhere as advocated in Tricon.”Footnote 33 United States diplomats provided the supporting documentation behind several Latin American governments’ formal protests.Footnote 34 Time would tell if the US-orchestrated pressure on Nasser would yield more significant results.

While working behind the scenes to isolate Cuba and Egypt, State maneuvered in similar ways against the Soviet Union, working through the Latin American delegations in the OAS and the UN. These moves, initiated while the Tricontinental delegates were still in Havana, sought to catch the Soviets in even greater contradictions than the Egyptians; not only had well-connected ruling party affiliates attended the conference, but in Moscow’s case they had also publicly pledged – in contrast to their secret agreements at the 1964 Havana communist conference – to support the armed ouster of Latin American governments with which the Soviets maintained official diplomatic relations. Sharaf Rashidov, head of the Soviet delegation, was First Secretary of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan and an alternate member of the Presidium of the Central Committee in Moscow.Footnote 35 At the Tricontinental, Rashidov pledged “our fraternal solidarity with the armed struggle of the Venezuelan, Peruvian, Colombian, and Guatemalan patriots against the lackeys of imperialism.”Footnote 36 It was a contradiction that the US government would productively exploit over the course of 1966.

The United States did not initiate the idea of action through international organizations; rather, the initiative can be traced to the Peruvian government, which requested and received US support for action at the OAS and UN in an exchange of letters begun on January 15.Footnote 37 But State seized the opportunity provided by the Peruvian initiative and worked to broaden and intensify Latin American governments’ condemnation of the conference and of the Soviet role in particular. The US embassy in Lima and US representatives at the OAS and UN encouraged the Peruvians to launch formal protests and to bring in other regional governments as co-sponsors.Footnote 38 After (as Ball wrote) “cooperating with Peruvian del[egate] to OAS in developing his presentation,” US diplomats looked on approvingly as Peruvian Ambassador to the OAS Juan Bautista de Lavalle decried the conference and called for a special meeting of the OAS Council for January 24.Footnote 39 At that meeting, Lavalle took the lead in denouncing the Tricontinental as a whole and Soviet support for subversion in the hemisphere in particular. He submitted a resolution, drafted by the State Department, to have an OAS committee investigate the conference and refer the results to the UN.Footnote 40

Radio Havana belittled the OAS as “the Yankee ministry of colonies,” claimed that the “hysterical response from the North American imperialists and their obliging Latin American lackeys” was “to be expected,” and vowed that the Tricontinental’s resolutions would be carried out.Footnote 41 While knowing better than anyone the degree of truth behind Havana’s invective, National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy approved of the direction the Tricontinental’s aftermath was taking. Bundy wrote to President Johnson of the “most welcome development” of the Latin Americans’ action at the OAS and informed his boss, “We are encouraging them in these moves and capitalizing on the propaganda advantage which the Havana meeting affords … We are working to get editorials and articles published in our press, as well as the Spanish editions of Life and Reader’s Digest. Through State and US I[nformation] A[gency], materials on the meeting will be reaching friendly editors, columnists, and writers” throughout the region.Footnote 42 In at least one case – that of Uruguay – a USIA-produced documentary on the conference aired on prime-time television.Footnote 43 From the highest levels in Washington down to Latin American newsstands and living rooms, the counterrevolution in the international public sphere was in full force within weeks of the Tricontinental Conference.

After subtle but firm arm-twisting by US diplomats in a number of Latin American capitals, meetings between Peruvian and US diplomats to finalize language, and a phone call and last-minute note from Rusk to stiffen Peruvian resolve, Lavalle submitted a resolution on the Tricontinental Conference that was approved by the OAS Council on February 2.Footnote 44 “This policy of intervention and aggression in the hemisphere on the part of the communist states,” it declared, “constitutes a violation of the principles of non-intervention … and of the self-determination of peoples” as upheld in UN General Assembly Resolution 2131 of December 21, 1965, and in the OAS Charter. The policy, furthermore, “endangers the peace and security of the hemisphere.” The resolution condemned in particular the open participation of officially sponsored delegations from countries that voted in favor of Resolution 2131.Footnote 45 Ironically, the Soviets sponsored that resolution as a means of embarrassing the United States over its Dominican and Vietnamese interventions.Footnote 46 The OAS resolution was the first time the organization specifically and collectively denounced the Soviet Union and the first time it filed a resolution with the UN.Footnote 47 Diplomatically, the Soviets were caught in an awkward and rather unpleasant situation.

While it stopped short of requesting action in the UN Security Council (where Moscow wielded a veto), the submission of the OAS letter of protest to UN Secretary General U Thant on February 7 escalated the international war of words over the Tricontinental.Footnote 48 On February 10, Castro sent an open letter to U Thant rebutting the OAS charges. Highlighting the “cynicism” of governments such as Costa Rica, Honduras, and Brazil that condemned “outside intervention” by Cubans and Soviets but actively participated in the US-led OAS intervention in the Dominican Republic, Castro labeled the American governments condemning the Tricontinental “the most servile instruments of Yankee imperialism in Latin America,” who enabled the “exploitation of their own countries” by the United States.Footnote 49 Castro’s (unsurprising) defiance suggested his continuing adherence to the OSPAAAL project.

Cracks were appearing, however, between the Soviet and Cuban positions. In the pages of Izvestia, Moscow had earlier labeled the OAS proceedings a “dirty farce” and claimed that the State Department was behind the action of its “satellites.”Footnote 50 It continued in February to publicly defend Rashidov’s actions and attribute the OAS furor to Yankee machinations.Footnote 51 Privately, however, Moscow appeared to be retreating. Rusk claimed that “Soviet diplomats in Latin America and UN now busily backpeddling [sic], when officially confronted by LA Governments, in attempt disassociate Soviet Government from militant resolutions and speeches of Tri-Continent Conference, particularly Rashidov’s statements.” He urged US embassies to take “appropriate steps … to expose Soviet doubletalk” and to encourage their host governments that maintained relations with the Soviets to formally confront the local Soviet ambassador.Footnote 52 The Brazilian and Uruguayan governments, at least, appear to have done so, and the Chilean ambassador to Moscow was notably recalled the next week “for consultations.”Footnote 53

By the spring of 1966, the Soviets and Cubans, two of the most important players in the putative Tricontinental movement, appeared to US observers to be working at cross-purposes in Latin America. The Cuban media were conducting what struck the US press as a particularly strident propaganda barrage against hemispheric rivals.Footnote 54 By contrast, in March the State Department interpreted a pattern of Soviet trade initiatives in the region to be “one means of placating and ‘buying off’ Latin American protests and resentment over [the] Tri-Continental Conference.”Footnote 55 After a rhetorical flirtation with armed struggle in response to Cuban- and Chinese-inspired pressure between 1964 and the close of the Tricontinental, the Soviets appeared to be reverting to their advocacy of the vía pacífica in the face of diplomatic pressure from Western Hemisphere governments. Latin American pressure over the conference, encouraged and facilitated by the United States, helped to distance Moscow from the Tricontinental program, limit its Soviet support, and exacerbate tensions between Havana and Moscow.Footnote 56

As the OAS and UN actions and the divergence of Soviet and Cuban positions played out, Washington came to see the Tricontinental as a diplomatic success for the United States. The National Security Council informed the president that the conference continued to be a “propaganda boon for us in the Hemisphere,” citing the OAS resolution and letter to U Thant, along with Moscow’s perceived reversal.Footnote 57 Citing Castro’s “insulting” letter to U Thant and the ensuing withdrawal in protest of a Chilean congressional delegation from a visit to Cuba, the NSC declared on February 18, “We are getting excellent propaganda mileage from the Tri-Continental Congress, much of it generated by the Cubans and Soviets themselves.”Footnote 58

Washington did not declare victory, however. The OAS committee investigating the Tricontinental issued its preliminary report in April 1966, warning that OSPAAAL “constitutes a positive threat to the free peoples of the world, and, on the hemispheric level, represents the most dangerous and serious threat that international communism has yet made against the inter-American system.” To defend against Cuban, Soviet, and other communist subversion, the report recommended that the American governments better “coordinate their security and intelligence activities” while undertaking “an intensive, coordinated, constant, and organized propaganda campaign in favor of democracy.”Footnote 59 Publicly at least, hemispheric governments continued to express concern about the Tricontinental movement’s revolutionary threat in order to keep the pressure on Havana.

That summer, the US Congress entered the picture as a new institutional player also emphasizing OSPAAAL’s threat. In May the House of Representatives Republican Task Force on Latin America, chaired by Bradford Morse of Massachusetts and Donald Rumsfeld of Illinois, criticized the Johnson administration for not responding vigorously enough to “the magnitude of the danger of subversion to existing governments” that OSPAAAL posed.Footnote 60 In June, the Internal Security Subcommittee of the Senate released a study of the conference, anticipating “the immediate and massive intensification of terrorism and guerrilla activity throughout the Americas, as well as in Asia and Africa.” It too questioned the administration’s response:

It is humiliating enough to have the international communist conspiracy seize control of a country only 60 miles from American shores, and maintain itself in power despite all the pressures we have thus far brought to bear. It becomes a thousand times as humiliating when that country is transformed into a headquarters for international revolutionary subversion while the OAS and the mighty United States of America look on, helpless and apparently incapable of any decisive action.

The recommended policy response, however, was essentially the same as that of the OAS committee: greater vigilance and enhanced cooperation between American governments on intelligence and counterinsurgency.Footnote 61

In addition to pressuring the executive branch for a harder line in the hemisphere, Congress held one other card to play against the Tricontinental movement: foreign aid. As early as February, the House inquired to the State Department about the precise makeup of the conference delegations, whether any of those governments officially or semi-officially represented were receiving US aid, and, if so, whether an aid cutoff could be used as leverage against the movement.Footnote 62 Ball had urged US embassies in Africa to advise their hosts of possible congressional reprisals against African governments that had encouraged or even allowed their nationals to attend the Tricontinental, with a view toward promoting a crackdown on those delegates and their organizations.Footnote 63 In the summer of 1966, around the time of the Senate study and the House Republican outcry, Congress amended the Foreign Assistance Act in order to deny aid to “any country … which hereafter is officially represented at any international conference when that representation includes the planning of activities involving insurrection or subversion.” Rusk later urged all diplomatic posts to “drop a word to the wise” to foreign governments about the new rules of the aid game in advance of future solidarity events.Footnote 64 Just as the State Department had sought to use the Tricontinental Conference as a pretext to widen the “Free World” embargo on Cuba, Congress sought to use economic denial as a means to smother the nascent Tricontinental movement in other Third World countries.Footnote 65

Washington’s attempted use of economic leverage over its troublesome aid recipients demonstrates the essential conformity of its policies to the neocolonial caricature depicted at the Tricontinental. So, too, did State’s behind-the-scenes maneuvering at the OAS and UN. The sum of these various initiatives by the summer of 1966 amounted to a two-track policy. Publicly, Latin American governments, the OAS, the Johnson administration, and Congress vehemently denounced the conference and trumpeted international communism’s threat to hemispheric security. Behind the scenes, the national security and diplomatic apparatus was sensitive to the solidarity movement’s internal divisions and viewed the conference as an opportunity to exploit. The CIA, for its part, was skeptical about a potential upsurge in Cuban aid to insurgencies in the wake of Castro’s rhetorical escalation, reporting that “to date our information does not show that this interest is being translated into new levels of concrete Cuban assistance. Similarly,” the CIA added, “it is uncertain if the Latin American and tri-continental organizations established at the recent Havana conference will be able to promote ‘revolution by committee’ any more effectively than Havana has unilaterally in the past.” Castro seemed inclined to exploit the propaganda value of calling for revolution and to proclaim Cuban solidarity with the revolutionaries, but he appeared loath to incur actual risks by providing significant tangible support to the guerrillas. “Castro’s more prudent subversion policy,” the agency concluded, “means that now, more than ever, the burden of carrying out revolutions rests with the local revolutionaries themselves.”Footnote 66 Therefore, it makes sense to view Washington’s publicly expressed fear and outrage as utilitarian: the greater the alleged threat from Cuban and Soviet-sponsored insurgency, the more justified was the counterattack.

“Counterproductive”

By the end of 1966, this counterrevolutionary program appeared to be succeeding. The US press and State Department continued to warily observe Cuban efforts to foment guerrilla movements in Latin America, for example, through alleged gunrunning in Guatemala and landing guerrillas in Venezuela; but effective counterinsurgency and internecine divisions among the rebels, these observers claimed, meant that these efforts amounted to little.Footnote 67 Both the New York Times and the State Department noted OSPAAAL’s announcement in November of its intent to establish schools in Cuba and North Korea “to train political cadres for revolutionary activity on the three continents.”Footnote 68 However, Rusk’s assessment was that, while keeping an eye on OSPAAAL’s intentions, the “Department does not foresee OSPAAAL achieving immediate widespread increase [in] violence on any continent … Moreover OSPAAAL decision provides more fuel for continuing attack on Tri-Continental activities.” True to form, Rusk suggested “avoidance [of] direct American attribution” as embassies worked to drum up publicity and criticism in the local press.Footnote 69 Another round of OAS condemnation and Cuban rebuttal played out at the UN in November and December along much the same lines as before, with the OAS condemning communist subversion, urging security cooperation, and calling upon more states to join the blockade of Cuba, while the Cuban Foreign Minister denounced Yankee and OAS hypocrisy in reply.Footnote 70

By the end of 1966, the Tricontinental revolutionary organization had failed to cohere as a tangible entity beyond the posters and journals being put out by the OSPAAAL publishing house in Havana and the unilateral initiatives of the Cuban government. Moscow continued to back away from its flirtation with armed struggle in Latin America and continued to expand its investment and diplomatic initiatives under the watchword of peaceful coexistence.Footnote 71 The US ambassador in Cairo observed that the Egyptian government was “embarrassed” by its pledge to host the Second Tricontinental Conference in 1968 and was resisting Cuban pressure to begin preparations while attempting “to either evade or postpone” it entirely. The Latin American embassies in Cairo, led by the Brazilians and Chileans, laid plans to jointly threaten the rupture of diplomatic relations with Nasser if the conference went ahead. Backed by the Soviets, Cairo eventually withdrew its personnel from the OSPAAAL secretariat and ceased participating in OSPAAAL activities, although Nasser continued to support certain African and Arab liberation movements unilaterally. Meanwhile the Sino-Soviet and Sino-Indian rifts, the collapse into incoherence of Chinese foreign policy during the Cultural Revolution, and the likelihood of boycotts left the bi-continental AAPSO conference scheduled for Beijing in 1968 virtually dead as well.Footnote 72 Neither conference would ever take place. Internecine rivalries and the backtracking of key patrons, exacerbated by Latin American diplomatic pressure that was both spontaneous and facilitated by the United States, led to the stillbirth of an organized OSPAAAL movement in Africa and Asia and left Castro as its sole effective patron in the Americas.

Havana appeared to maintain its enthusiasm for promoting armed revolution in Latin America and the broader Third World. After Che Guevara’s guerrilla column withdrew in failure from the (former Belgian) Congo at the end of 1965, the Cubans returned their principal focus once more to Latin America, as Castro prepared to host the first conference of the Latin American Solidarity Organization in 1967.Footnote 73 But with logistical support from Havana difficult to maintain and Bolivia’s Communist Party and its Soviet patrons actively hostile, Guevara’s next mission, in Bolivia, ended in failure and martyrdom.Footnote 74 The juxtaposition of Guevara being named chairman in absentia and “First Citizen of Latin America” at the OLAS conference of Latin American communists and guerrillas in Havana in July 1967, on the one hand, and his lonely death in the Bolivian outback at the hands of CIA-supported Bolivian rangers in October, on the other, encapsulates the fate of the Tricontinental organization as a patron of armed struggle.

The US government was largely unfazed by the OLAS conference and its aftermath. The CIA observed that “quarreling among the Latin American communists was at an all-time high” between the pro-Castro and pro-Moscow currents among the assembled revolutionaries and between them and those orthodox communists who stayed away entirely. Calling the bluff of several pro-Soviet delegates who threatened a walkout, Castro allowed a vote on a secret, unpublished resolution chastising “certain socialist countries” for their programs of trade credits and technical aid to Latin American governments, including dictatorships and oligarchies that repressed guerrilla movements and communist parties; the measure passed, fifteen votes to three, with nine abstentions. With this denunciation, the rift between Cuba and the Soviets over the guerrilla struggle in the Americas became definitive. The CIA accordingly believed that any plans laid for new guerrilla activities would be slow, sporadic, and undermined by infighting: “In short, the OLAS conference is not likely soon to lead to significant communist advances in the hemisphere.”Footnote 75 Che Guevara’s death in Bolivia in October seems to have reinforced US officials’ confidence that insurgency in the hemisphere could be defeated and that support for it would fizzle out.Footnote 76

Another OAS meeting in response to the OLAS conference condemned anew Cuban “acts of aggression” in Venezuela and Bolivia; expressed serious concern to those governments offering support for OSPAAAL; called upon them to withdraw their support for the organization and its subversive activities; urged OAS members jointly and individually to confront governments supporting subversion in the hemisphere; and renewed the appeal to free world governments to restrict their trade with Cuba. National Security Advisor Walt Rostow wrote to President Johnson, “These resolutions will not topple Castro, but they provide OAS-sanctioned levers for pressuring our European friends and Soviet bloc countries to put the heat on him.”Footnote 77

By 1968, therefore, the solidarity conferences and their message of Cuban-sponsored hemispheric revolution contributed to the further estrangement of Cuba from the hemisphere and the straining of Cuba’s relations with those European and Soviet-bloc countries with which it maintained relations. With Cuban-Soviet relations at low ebb and the OAS governments increasingly diligent in coordinating and implementing counterrevolutionary programs, Castro was by 1968 in an exceedingly weak position to attempt significant tangible support to revolutionaries in the Americas.Footnote 78 For nearly a decade, Cuban encouragement and tangible support for guerrilla movements in Latin America would be considerably more circumspect and modest, and it would prioritize restoring economic and diplomatic relations with its neighbors.Footnote 79 Cuba’s major military interventions in Africa in the 1970s and 1980s, while motivated in part by a sense of revolutionary internationalism, were undertaken as unilateral initiatives of national foreign policy, despite Soviet reluctance, to support recently established revolutionary governments rather than guerrilla insurgents.Footnote 80

Assessing Cuba’s foreign policy prospects in mid-1968, US intelligence analysts concluded that the entire OSPAAAL and OLAS project had proven “counterproductive” for Castro.Footnote 81 The State Department’s internal history of the period asserts, “Because of the US activities, Latin American-OAS-UN opposition to both conferences was better organized, more completely documented, much stronger, and considerably more effective than it would have been otherwise.”Footnote 82 Washington’s counterrevolutionary activities certainly deserve some modest share of the credit or blame for the solidarity movement’s struggles to coordinate support multilaterally and to achieve armed revolution in the Americas, Africa, or Asia. But Washington’s primary role was to exacerbate and benefit from the internal contradictions already well established among the movement’s various state and nonstate constituencies. By seeking to sow division and disillusionment among the diverse revolutionary forces of the world, US officials lived up to the nefarious image of them painted at the Havana conferences, with greater effectiveness than the assembled revolutionaries had hoped.

Maintaining a sense of perspective, however, is important when assessing the early history of the Tricontinental and Washington’s response. US officials’ principal concerns with the Tricontinental, OSPAAAL, OLAS, and the revolutionary project they represented were about what Marxists might call the objective conditions and the correlation of forces with respect to the prospects of revolution. Government officials in the United States were primarily concerned with questions of the movement’s capacity to provide material support (funds, weapons, manpower, training) for guerrilla fighters; they were also focused on diplomatic questions at the UN and OAS of how to use the conferences as a cudgel with which to beat Havana and Moscow in order to further isolate Cuba economically and diplomatically from the “Free World” and, if possible, to isolate Havana from Moscow, Cairo, and other revolutionary governments. Through these lenses, the counterattack against the Tricontinental in 1966–68 does appear successful.

A distinction must be drawn, however, between OSPAAAL and OLAS’s role as headquarters, clearinghouse, training ground, and support network for regional and global revolution, on the one hand, and the Tricontinental’s role in articulating and inspiring a discourse of Third World solidarity and revolutionary internationalism, on the other. As several scholars, including some in this volume, have shown, the Tricontinental embodied and gave voice to a transnational discourse of revolution that continued to inspire revolutionaries around the world over the ensuing decades. With the exception of Southern Africa, where Cuba’s contribution appears to have been of critical, even decisive, importance, the US government and its counterrevolutionary allies were fairly effective in undermining and containing OSPAAAL, OLAS, and the Cuban government as material supporters of revolution; but over the following two decades, from Palestine to Central America, Southern Africa to the Southern Cone of South America, Vietnam to US cities and college campuses, containing the idea and example of international and transnational revolutionary solidarity would prove to be a far more difficult task.