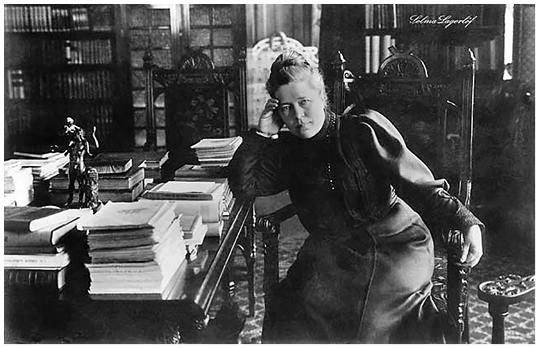

In 1909, Swedish author Selma Lagerlöf received the Nobel Prize in literature (Figure 2.1). She had written widely in many genres. Her most recent major work was a two-volume reader for Swedish primary schools, The Wonderful Adventures of Nils (1906–1907). The book became an instant success. Not only was it used in schools around the country for the better part of the twentieth century, but it was also read by the general public as a narrative geography of Sweden.Footnote 1 Soon translated into dozens of languages, the book served as a saga version of a real country, a strange northern kingdom straddling the Arctic Circle, with deep forests and shining glaciers, close to the North Pole. It mixed historical, cultural, and economic aspects of the old nation, now rising to a new industrial prowess based on rich natural resources, engineering ingenuity, social cohesion provided by strong social movements, and old moral and civic standards sometimes summarized with the single word “Lutheran,” but perhaps better captured as “trust.”

Figure 2.1 Selma Lagerlöf, Nobel Prize-winning author and early conservationist, at her desk while writing Nils Holgersson in the early 1900s.

It was profound change, deep modernization, presented as fable and fantasy. From the back of a goose, high above the long north-south stretch of the Swedish landscape, five-year-old Nils, the son of ordinary farmers in the south, could look down on the wonderland that was his home. There were fields, there were factories, and there was – as Nils gradually discovers as the goose carries him northward towards the newly-established iron-mining town of Kiruna – anything that a boy, or a king or queen for that matter, could dream of. In fact, not a single member of the entire population of Sweden could possibly find anything lacking in such a richly endowed country that was surely a gift from some higher authority. Could any nation be better?

Nonetheless, in the same year as she received her Nobel Prize, Selma Lagerlöf also became a member of the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation (SSNC). Today, an environmental NGO with over 200,000 members, the SSNC started as a small elite organization with academic naturalists, legal specialists, intellectuals, and industrialists among its ranks.Footnote 2 It frequently provided expert advice to the government. Several of those among the top strata of the SSNC were members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which in the absence of a public agency for the national parks of Sweden – the first ten were inaugurated the very same year, 1909 – served as the semi-official authority on issues to do with nature. This meant that nature was a strong interest of the state.Footnote 3 Sweden was the first country in Europe to establish national parks for the protection of nature. Public opinion in favor of national parks had emerged in Sweden back in the 1880s with reference to Yellowstone and other such protected areas in the United States. The immediate inspiration for the final push came from the debate in Germany, although similar parks were not established there until much later.Footnote 4

The involvement of the state should not be seen as a sign that all was well in Swedish nature. In fact, the opposite was the case, which was the reason for Selma Lagerlöf to join the SSNC. Like many others, across the socially and economically grossly unequal Swedish population,Footnote 5 she was upset with the state of nature in the country that she had researched so carefully and knew so well from travels across all of its twenty-five provinces. Sweden’s forests were cut down at alarming rates with weak schemes to replant them, until new legislation was enacted in 1903 to rescue and secure the long-term use of crucial timber resources.Footnote 6 Rivers and lakes were polluted to such an extent that fish populations were impacted, as was the health of people when swimming or doing laundry – usually outside for most of the year in rural areas where most people still lived – in affected water bodies.Footnote 7 Even in the cities, evidence mounted that increasing portions of the population lived under unhealthy conditions, especially children. A debate soon raged on the dangers of urban life, largely driven by the political far right, which asserted that the blood and soil of the land were the true roots of a sound and healthy nation. It was in the smoky cafés of the city that dangerous radical ideas emanated, threatening to undermine the stamina and resistance of the innately loyal and patriotic rural Swedes.Footnote 8

Nature – A National Issue of the Highest Order

Names like that of Selma Lagerlöf, along with August Strindberg, the foremost in Swedish literature, drew attention to the issue of nature conservation, which became one of the most pressing issues in Swedish political debate in the decades around 1900. This was also the period of Sweden’s rapid industrialization. There was of course a connection between these two major developments in Swedish society. Neither agriculture nor fisheries lacked environmental effects, but it was the industrial transformation and the expanding technologies of energy, including heating cities with coal, gas, and oil, that affected nature in an array of tangible ways.Footnote 9 In addition, this period also saw the privatization of state forests and the liberalization of forest and resource legislation that, alongside the mechanization of agriculture, gave industry advantages and favored large-scale farming over small-scale farming.

Propelled by a series of bad harvests in the 1860s, the structural changes in the economy caused mass unemployment and the emigration of more than a quarter of the population of around five million up until the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Although wealth also grew considerably in certain periods, there was a widespread perception that Sweden was a country in deep crisis. The visual image of the nation was not just Nils’ bird’s-eye view of its beauty and natural resources. If you opened the daily newspapers, especially the satirical press, and if you came across pamphlets and novels on the state of Swedish forestry, you would find cartoons of a nature stripped to the bones and starving people in communities left in disarray, easy prey for the infamous peddlers of single tickets to the United States.

Nature was becoming a national issue of the highest order. It was also an issue linked to many other social and economic problems of the day. Self-subsistence was still common in Sweden as part of a household’s income. Forests and wetlands were regarded as common lands. In the sparsely populated country – with less than a tenth of the population density of Denmark or the Netherlands and a fifth of that of Germany and the United Kingdom – private property was in general not a hindrance to pick berries, fish in lakes, and keep cattle grazing in the forest. Nature had a commonality to it that gave the issue resonance when it was addressed by elites. In Swedish nationalism, nature already played a part and in the period of pronounced and vitalized nationalism sparked by the industrial transformations, nature became a unifying force, an element that many Swedes had a relationship with, and were now actively encouraged to cherish. They learned the value of nature from schoolbooks, such as Lagerlöf’s, but also from their own experience of it, as an ultimate safeguard against starvation, although for many, North America remained a more attractive alternative.

Nature was protected at least in part because it was loved and respected. It was also given a language, both written and visual. Not unlike many other countries in Europe and the Western world, nature was nationalized through a series of intervening and constructing institutions: schools, museums, visual art, music, and literature, also intended to impose Swedishness on minorities such as the Sami, through a special kind of “Nomad schools” system, and the Torne River Valley Finns in the north.Footnote 10 Swedish nature turned out to become an iconic centerpiece of an imagined community, with an intensity that was exceptionally strong and profound. Swedes came across as an avid, almost genetically predisposed “nature-loving people,” naturälskande folk, as Sweden’s second Nobel Prize-winning author Verner von Heidenstam called it.Footnote 11 A massive body of literature in multiple genres was published in the decades around 1900 that articulated and spread the new nature-based nationalism. One, odd but telling, example was statistician Gustav Sundbärg’s remarkably nonstatistical and much-debated book, “The Swedish People’s Character” (Det svenska folklynnet), published as part of the massive parliamentary inquiry into emigration that had become a de facto national trauma. Like so much else of the knowledge production surrounding the awkward, emigrating, and despairing Swedes, it focused on the disproportionate passion for nature in this country, which, Sundbärg argued – coining what would become a long-lived stereotype – was also a nation of “engineers,” thinking rationally, if not terribly deeply. Swedes were loners, lacking psychological interest, but they could get things organized, and nature was their central interest, he maintained, and few disagreed.Footnote 12

This line of thought brought out sympathies and passions among Swedes, and the sheer mass of this pseudoscientific propaganda helped build a deepening sense of true Swedish identity for the new Swedish nation that emerged with industrialism. Some of it was, at least in part, designed to instill in Swedes such love for their beautiful country with poetry of “pine and oak” that they might hold back their impulse to emigrate. Nature was also a source of the raw materials that underpinned Sweden’s new industrial wealth, from minerals and timber to turf and hydropower. Although there were deep controversies over the best way to utilize these resources – to prioritize industry or build self-sustaining agrarian societies, the classical conflict of Industriestaat gegen Agrarstaat – it could not be denied that the wealth of nature provided the option to choose. Whatever path the nation chose to embark upon – turning nature’s bounty into a commodity or preserving nature’s beauty as an ecological asset – nature was the core of the national project. With nature, Swedes would become rich, materially or spiritually, or even both.

Nature as National(ist) Ideology

The fervor with which this natural nationalism was practiced in the decades around 1900 never fully returned. The war poured cold water over some of the sentiments. Emigration stopped almost completely during the war years and never returned to pre-war levels despite the considerable social tensions and economic hard times under which the Swedish population suffered toward the end of the war. Instead, democracy and full voting rights for women and men, decided in 1919 and realized in the 1921 elections, signaled a turn toward social and economic affairs. Nonetheless, nature as a theme stayed on, although it turned more social. During the war, travel was difficult and in the interwar years, “Social nature protection” became a catchphrase, especially from the political left, where there had always been some skepticism toward the most solemnly patriotic versions of the turn of century nature worship. Instead, periurban nature was presented as the vernacular alternative. Housewives of all classes were mobilized to take children outdoors.Footnote 13 Schools were required to apply “outdoor days” to make sure that healthy traditions were passed on to the coming generations. The SSNC advocated arranging accessible walking paths and recreation facilities near towns and cities for the large majority of families who couldn’t afford adventurous trips to the high mountains or accommodation in resort hotels. Social and urban planners soon followed suit. Swedes were expected to go to the forest to pick berries and mushrooms, and they did. Vernacular subsistence habits such as fishing and hunting were turned into widespread pastimes, and they established their own, soon sizable organizations with memberships that by mid-century reached more than a million, out of a total population of little more than six million.

Friluftsliv became the new term for the out of doors. By the early 1930s, with the rise of the soon famous Swedish welfare state, which drew such interest abroad, nature practices were becoming integrated into welfare thinking and politics. The name for that was “socialt friluftsliv,” or “social out of doors.” It was advocated particularly by the political left. Physicians, educators, and social reformers argued that social cohesion and public health, as well as general education (in Swedish bildning, after the German word Bildung), would improve if people experienced nature firsthand and not just through books. Social movements and their rising civic, but partly publicly supported, study organizations, under the name folkbildning (general education for the people), were among the pioneers. The practice of friluftsliv, however, went beyond organizations and became common also on the household level. It was featured in the Stockholm exhibition in 1930, a showcase of Swedish modernity, and in 1936, friluftsliv received its own special exhibition in Ystad, a city on Sweden’s southern coast. It demonstrated how nature practices had already become a civic, commercial, and political issue of some status.Footnote 14

In this way, the first half of the twentieth century was a long period of “education in nature” that reached the better part of the Swedish nation. Already close to nature thanks to a vast territory with a thinly spread population and small cities – the largest, Stockholm, had a mere 300,000 inhabitants in 1900; London had five million, while Paris and Berlin had three and two million, respectively – Swedes were accustomed to nature and culturally prepared to appreciate it. It was a precondition for both health and wealth, and for welfare, in a period that also saw a soon-to-be world-famous welfare state take form, for which the nation took great pride. The two went together in progressive legislation enacted in the early 1940s on rights of access to lakes and rivers, which followed an already widespread “everyman’s right” to waterways and almost all land, private and public.Footnote 15 A comprehensive infrastructure of paths and trails emerged as new practices of pastime nature use expanded in the twentieth century, with Sweden as a pronounced version of an international trend.Footnote 16 The growing cities also enjoyed an active planning movement with green areas and parks as a fundamental feature.Footnote 17 Part of this national nature project was to bridge social divides and foster Gemeinschaft and cohesion. Ethnic and racial divides were less emphasized, not because Sweden lacked immigrants but because their numbers were modest and integration was largely successful. Racial debates around who had access to nature, well known from colonial and postcolonial contexts,Footnote 18 were not at the forefront until the very end of the century. Nature was a unifying, nation-building project, widely embraced in Swedish society. It enjoyed official support and rested upon a growing number of civil society institutions such as popular movements, out-of-doors associations, and sports clubs.

This modest, vernacular cult of nature was part of a Swedish exceptionalism that only expanded in the coming years. Sweden remained neutral during World War II – a position widely supported then, but critically discussed laterFootnote 19 – with unusually close and congenial relationships between industry and trade unions and between both these interests and the state.Footnote 20 It was in fact this corporatist model of close ties and collaboration between different camps and classes of Swedish society, and between its geographically and socially quite diverse provinces, that admirers from abroad found so unlikely, advanced, and “modern,” to quote what is likely the most recurring term in representations of Sweden. The iconic Stockholm Exhibition of 1930 became the epitome of this image. Enormously popular, with more than four million visits in a country of six million inhabitants, the exhibition employed a nationalist narrative, stressing history, to define the “Nordic race” and evoke a glorious, industrial future built on nature’s resources.Footnote 21 Nature as scenery, beauty, replenishing source, or as ecology and preservation was not at the forefront. Seen from a later vantage point, the interest among foreign commentators was not directed toward the exceptional relations between people, state, and nature that were nurtured as a vital part of this somewhat corporatist version of a cohesive nation and its identity. They focused more on the social and economic dimensions, perhaps because in other countries, nature was not always considered part of the welfare state agenda.

This means that significant early contributions in Sweden to what was later termed “environmentalism” or ecological thought did not become very well known internationally. This was also true of another strand of nature interest that served as a countercurrent to mainstream modernism, but flourished in certain environments, especially in the 1930s and 1940s. While the expanding connections between nature and welfare were developed largely from the reform-oriented parts of the political spectrum – social democrats and liberals – a somewhat more skeptical approach arose from within the much smaller communist left, which had more urban tastes and, embracing class confrontation, disliked the unifying nationalist overtones ascribed to nature.

The stronger and more persistent countercurrents were conservative and informed by hierarchical and socio-biologist figures of thought. These nuances in ideologies around nature started to appear in the Swedish discussion around the time of World War I. A more profound refraction between distinctly opposite positions only became manifest when democracy was fully established in Sweden, and after the Revolution in Russia in 1917, the rise of Communism, and the harsher ideological climate of the 1920s. In this conservative strand, nature was mixed with ideas of race and biology. The first tendencies in this direction had no particular politics. It has been observed that ecology and “Darwinist” camouflage were present in Swedish landscape painting from around 1900, for example, in the work of wildlife painter Bruno Liljefors. At the time, however, no one could have imagined that his work would become much appreciated in the nature-loving Third Reich, which in and of itself could not have been imagined in 1900. Nor could anyone have guessed that Liljefors only a few decades later would win a prestigious prize named after a leader who would orchestrate and symbolize some of the most atrocious evils ever committed, “der Grosse Preis Adolf Hitlers.” The Prize was presented to an aging Liljefors, who was himself in attendance, in 1937 at the Internationale Jagdausstellung in Berlin, a major event in the Nazi calendar that year. A pet project of Reichsforstmeister and Reichsjägermeister Hermann Göring, the exhibition had animal painting and photography as one of its major themes and brought together the entire Nazi elite, including Hitler, Himmler, and Richard Walther Darré, the German Minister of Agriculture.Footnote 22

Conservationist care for nature and animals was present in many European countries and in North America as well. Germany is a case in point. Mountain landscapes had a particular prominence. They were the subject of an aesthetic cult, and Bergfilme was a popular genre. In Nazi ideology, mountains and their summits had a special aura. The alpinist was a cherished social character, with his athletic prowess embodying both the longing for purification and the physical strength that the Nazis worshipped. Germany dispatched well-equipped expeditions to the Himalayas to search for the original Aryan Heimat and to demonstrate their obsession with the highest summits of the world. Nature was a hierarchy and at the top, closest to heaven, was the Übermennsch.Footnote 23 According to the same logic, aristocratic animals such as eagle, bear, and moose ought to be preserved, and landscapes and waterways serve as the nourishing soil and blood of the nation.Footnote 24

Such sentiments, fundamental for the Nazi regime, were distinctly less common in Swedish conservation circles, although they did exist in less pronounced forms and with ideas of a “Nordic” race and lifeworld as a common denominator.Footnote 25 Conservative nature lovers argued that Lapland in the north should be reserved as the ultimate wilderness where local people, including the reindeer herding Sami, should not be allowed to hunt charismatic birds and megafauna – the kind of “policing nature” policy that was practiced overseas among colonial elites. These outliers within the Swedish debate, with prominence on the political right and in certain academic circles, including museums,Footnote 26 were predominantly male and came across as puritan cousins of the aristocratic “Teddy Bear Patriarchy,” which Donna Haraway has identified as central to fauna conservation.Footnote 27 The male white upper class, who saw it as their prerogative to visit Africa to shoot elephants and rhinos, did not consider their hunt as a mere pastime but sublimated their pursuits as primarily moral and scientific.Footnote 28 The Godfather of this particular element of Western imperialism was President Theodore (“Teddy Bear”) Roosevelt, who helped establish national parks and monuments such as Crater Lake and the Grand Canyon.Footnote 29 His hunting adventures were documented in Roosevelt in Africa (1910), an early prototype of the genre of safari films.Footnote 30

Realist Sustainability

Post-1945 developments gradually marginalized most of what remained of the conservative, patriotic version of nature. Its ideological foundations had become discredited and impossible due to the war and the complete disaster, not only for aggressive nationalism but also for ideologies of race.Footnote 31 The tradition still played some role in the popularization of nature and in connecting some of the Swedish self-understanding with strands of science, travel, art, film, and photography. The conservative appreciation of nature, ideologically cautious and diffident, that remained in the postwar decades pragmatically sided with mainstream welfare modernism, although it was less prone to take a vanguard role in legislation and activism. Nature, later “environment,” thus became one of several policy areas – such as defense, security, science, technology – where consensus reigned. Pragmatic solutions were prioritized, and as a gift in return, the Social Democratic Party, in government, save summer 1936, from 1932 to 1976, although in coalition during the war, made sure nature protection would not seriously oppose the interests of industry and resource extraction.Footnote 32 The party was always a broad church and although a more radical, environmental wing grew in the 1960s, it inevitably had to compromise with more traditional versions of modernity, more palatable to the trade unions and the low-income strata of society that remained the party’s chief voter base.Footnote 33

A pragmatic version of “eco-modernism” gained hegemony in Sweden, long before such a concept was even coined in the 1980s. A seminal work in that tradition was The Politics of Environmental Discourse (1995) by the Dutch political scientist, Maarten Hajer. It was a study of acid rain in Western Europe, but what made it influential was a simple and attractive policy idea: the environment is no reason to hold modernization back, but rather to speed it up. It came at a moment when such solutions were on the rise. Better incentives, distinct goals, certification of methods, and innovation in policy and technology would contribute to the efficient use of natural resources. Above all, economic growth did not stand in opposition to a healthy environment, an idea that had been talked about before, but in Hajer’s version was presented more coherently.Footnote 34 Although not precisely congruent with Social Democratic orthodoxy, these were ideas that they could just as well employ, and they did.Footnote 35 Domestically, the party had been constantly navigating issues of nature and the environment. When environmentalism grew in the postwar decades, the Social Democrats certainly did not lead the way as a political force on the issue, although many individuals within or close to the party were important voices. Momentum was brought to politics from the outside by popular movements, scientists, intellectuals, and artists.

Only in the 1960s did “the environment” begin to gain a significant position in the party. Olof Palme, who was a member of the government since 1963 and became party leader and prime minister in 1969, included the environment in his talks, articles, and books as the environment increasingly grew in importance. Still, he was always careful to connect environmental issues with more traditional Social Democratic concerns such as democracy, human rights, peace, and welfare. Whether addressing an audience at a May Day manifestation or speaking as head of the Swedish delegation at the 1972 Stockholm Conference, he found the nonenvironmental topics relevant to each audience that made the environment seem crucial to them. In and of itself, the environment was of little significance.Footnote 36 Other features of Swedish social and political life also go a long way toward explaining the politics of what we might call realist sustainability. The instrumentalist paradigm that sustainability, launched by the UN report Our Common Future (1987), sought to redress, perhaps even to challenge, had had a long time to grow and become established.

A tradition of political arithmetic had already gained ground in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, well before the tradition of sustained yield that arrived in Sweden from the German states in the nineteenth century.Footnote 37 Political arithmetic portrayed nature in this powerful Baltic nation as well-endowed and a divinely privileged repository of people (labor power), plants, and animals. Such ideas were present in an unusually articulated form in the patriotic economic botany of Linnaeus, who was an early voice of “ecological” and circular ideas avant la lettre. One example is his short thesis, Oeconomia Naturae (Husbandry of Nature, 1749), although he just as well fits a more extractivist-oriented “cameralist” approach to natural resources that also runs deep in Swedish nature practices.Footnote 38 In that respect, Linnaeus was a forerunner of both ecological modernization and care for nature as a divine gift. Industrialism in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries reinforced particularly the former tradition, placing pride in the fact that Sweden was rich in natural resources on which to build a new and glorious future.Footnote 39

The oft-proclaimed sensitivity for Nordic nature and its mythological dimensions displayed in the arts was growing alongside, or rather on top of, industrialized nature. It was the rise of the industrial economy, professional elites, and an urban middle class with deepening nationalist aesthetics and values, which formed the social basis of esteem for nature and, thus, for preservationist and conservationist policies in the first decades of the twentieth century. However, these groups were also quite sensitive to the demands of industry, and responsibility for the productive capacity of the nation was sometimes used as an argument to sacrifice precious forests, waterfalls, or marshes. Nature was the national common ground and the essential backbone of wealth, in particular on Sweden’s northern periphery, where the aboriginal Sami population was affected by continuous territorial and judicial setbacks as resource extraction rolled north to exploit its forests, iron ore, peat bogs, and waterfalls for energy, and land for agriculture.Footnote 40

The environmental issue has loomed large since the mid-1960s and onward. Compared to other countries, Sweden was early and comprehensive in its attempts to deal legally with issues such as vehicle pollution, work environments, acidification, and many other issues around the environment and public health. A full-time cabinet minister for the environment was appointed in 1986. The most significant characteristic of Sweden in this respect may be the relatively peaceful co-existence of the state with a growing environmental movement, which had considerable public support and attracted the attention of center-left parties and often the government. The green movements also enjoyed an expert role, dating back to 1909 with the SSNC as well as with the Samfundet för hembygdsvård (SfH), Society for Heimat, founded in 1916. If the interest of the SSNC was “nature,” SfH was engaged with “landscape,” especially landscapes where structures and infrastructure were to be built, or when older buildings or locations of cultural heritage were threatened by new development. Architects, archaeologists, planners, engineers, and other “spatial” and “temporal” experts were at the forefront, rather than natural scientists. Working closely with the widely spread Heimat movement, their structural role was the same as that of the SSNC: not opposing development, but brokering interests, finding a way forward.Footnote 41

This does not mean that the wave of radical environmentalism in the 1960s and 1970s did not represent something novel, in scope, intensity, and argument. It simply operated within an already rich institutional context with the capacity to co-opt and mainstream new initiatives and bend them to fit under the pragmatic umbrella of state authority. Furthermore, Sweden’s Green Party was formed. Although the Scandinavian countries’ role as early environmentalists and vanguard ecofeminists has faded somewhat into the background, it is an important feature to keep in mind if we wish to understand the rise of Swedish environmentalism. Before the 1980s, some of these green energies were obviously present in other political parties, most of which had to cede sizable numbers of voters and activists to the new Greens, with some exception for parties on the right, the Christian Democrats and the market liberal Moderate Party.

The Green folkhem

As we shall see in the following chapters, Sweden after 1972 kept working at the forefront of the international environmental agenda. At home, the pace forward was, albeit solid, not quite as impressive. The hegemonic Social Democrats, back in 1982 after six years of rare center-right government, continued to stay in power for another quarter century, except for three turbulent years under the Moderate Party leader Carl Bildt from 1991 to 1994.

Environmental issues kept rising on the agenda. In 1995, the newly installed Prime Minister Göran Persson launched a political idea that he called “the Green folkhem.” It alluded to a 1928 speech in Parliament by then party leader Per Albin Hansson. In his speech, later to become what is likely the most cited speech in Swedish history, Hansson had drawn upon a concept advocated by Swedish conservative thinker Rudolf Kjellén about a natural Heimat, a state that was at the same time geopolitically pragmatic, corporatist, fair, and caring.Footnote 42 Folkhem was the formative political idea that stood behind the kind of society described by Marquis Childs, and that the world admired with the Swedish model. It also became a concept used in Sweden, where it became so hegemonic that when historian Bo Stråth in 1993 wrote about the road then embarked upon by Sweden toward membership in the European Community, he could entitle his book Folkhemmet mot Europa. The word “mot” means “against.” The close folkhem community was distinctly local, national, and anti-cosmopolitan. This was in contrast to the more technocratic term “the Swedish model,” which, according to lexical data Stråth cites, was rather used retrospectively from the 1970s about the tradition in Sweden to seek consensus rather than confrontation, especially in the labor market and in avoiding strikes. A “model” could travel and be applied elsewhere, a “home” could not. Stråth also notes that the likely first use of the concept was as late as 1967, by French radical politician and journalist (founding editor of L’Express) Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber in his international bestseller Le défi américain: “le modèle Suèdois n’est ni Américan, ni Japonais.”Footnote 43 The original understanding that Sweden’s was a “middle way” had remained intact since the 1930s.

Göran Persson employed the folkhem brand – still useful, especially when the Swedes finally dared tie themselves to the mast of the European ship – for a new project, to package and sell the rising norm of “sustainable development.” The point was to deliberately hold on to homespun ideals but transform them appropriately. As usual, at no cost to the economy or people’s standard of living. The economy would grow, and Sweden’s deep economic crisis should be overcome. It was also a time when the environment was no longer, as during the Cold War decades, discussed as only a problem. Was it a thing of the past? Solutions, both technological and market-driven, would be increasingly forthcoming, some argued, most intensely from liberals and conservatives. American journalist Gregg Easterbrook’s influential book A Moment on the Earth (1995) was built on such eco-modernist optimism, congruent with the generally sanguine Western mood of the post-1989 moment. Easterbrook adapted Maarten Hajer’s academic approach and interesting hypothesis to deliver a downright verdict. Just add innovation and market forces, as Easterbrook speculated, and environmental regulation would be superfluous. Consumption was not a burden for nature, it was a driver of innovation that helped fund “best practices” according to the neoliberal handbook that had been rehearsed since the breakthrough years under Thatcher and Reagan.

The Swedish idea of the Green folkhem was surely articulated with a healthy distance to reckless neoliberalism. At the same time, it was not the old regulating policy that was presented. Even Scandinavian Social Democracy was changing. More than twenty years had passed since Stockholm 1972, new winds were sweeping through all policy areas, and the environment was no exception. It was a sign of Göran Persson’s political instincts that he tried to find a compelling idea, and name, for his basically pragmatic environmental politics. He calculated that sustainable development was the only game in town, the juste milieu between right-wing denialism and green radicalism, the path Social Democrats always favored. But it just didn’t fly this time. It was ridiculed in the liberal press and it seemed heavy-handed, a Keynesian crisis antidote with heavy investment on environmental sanitation of old mass housing suburbs, although it was essentially a continuation of slowly evolving Swedish policies. It followed very much Palme’s prescription: always make sure that green politics work in synergy with other reforms that will win votes.

Such a pragmatic approach had worked in helping to prevent the destruction of the ozone layer. Sweden played a key role in a longer-term process that led up to the 1987 Montreal Protocol, an international agreement meant to phase out ozone-depleting substances such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). Swedish scientists and government officials had at that point been working on the issue for many years. The Academy of Sciences had through its environmental committee taken a keen interest in ozone depletion in the mid-1970s, including organizing a conference in November 1976. What is more, CFCs also contributed to the greenhouse effect; the Academy’s interest in addressing such atmospheric pollutants thus demonstrated an early policy presence of the climate issue. On ozone issues, Sweden would work through UNEP, which in 1981 initiated efforts to create a global convention. Chemical meteorologist Henning Rodhe at Stockholm University, who worked closely with Paul Crutzen, later winner of the Nobel Prize for his research on ozone, gave a series of media interviews in 1986 and wrote an op-ed article in the Dagens Nyheter in October 1987. From the sidelines, environmental organizations supported policies to phase out ozone-depleting substances. Industry was, perhaps predictably, obstinate. The CEO of the Swedish industrial company Electrolux predicted that the unilateral ban in Sweden would lead to the demise of industry and lost jobs. Within a few months, he had turned 180 degrees on the policy, proclaiming that industries across Sweden were working to implement the ban. Political leadership was necessary. At first, the political right opposed the ban, while the Social Democrats and the Liberal Party wanted to introduce incentives and leave the issue to the market. The Left and the Centre Party, a de facto quite “green” political force at the time, were most decisively in favor of a radical elimination of CFCs. Finally, the government listened to the science and the growing choir of voices and changed its position. A contributing factor was the Green Party, which was by then an established presence in Swedish politics. The young party enjoyed tailwinds as the 1988 elections drew closer, with an enigmatic mass death event of seals on the Swedish west coast and a postponed phasing out of Swedish nuclear plants. It was also the long, hot summer in the United States, where Jim Hansen of NASA gave testimony before Congressional hearings in which he connected the extreme temperatures to an anthropogenic “Greenhouse effect.”Footnote 44

The Importance of Knowledge

In the decades that followed, other major political decisions were taken on taxes, chemicals, forestry, biodiversity, and finally on climate, where a comprehensive climate legislation framework was enacted by Parliament in 2017. These were not the only issues that were addressed, but they all sit well with the overarching pattern of Swedish environmental politics in the decades following the UN 1972 Conference, especially the fundamental role of knowledge and consensus culture in combination. Sweden was among the very first countries to introduce a carbon tax in 1991. By then, economic incentives had been debated in Sweden for some time. Just like in the case of ozone a few years earlier, pragmatic collaboration made the difference. Politicians from a broad spectrum of parties acted in liaison with government experts, civil servants, and research institutes, all raising their voices in favor of a carbon tax. Scientists such as Bert Bolin (climate) and Karl-Göran Mäler (ecological economics) offered their advice and had access to politicians through advisory groups. The SSNC, again, was active in providing proposals and documentation. The time was ripe. In the raging economic crisis in Sweden in the early 1990s, a broad tax reform was needed anyway and other energy taxes could be lowered as the carbon taxes were introduced. This stimulated domestic biofuels and propelled the phasing out of oil and gas from the heating sector.

Knowledge was central to progress in all these cases. This speaks in favor of an argument that has been made about Swedish domestic environmental politics in recent years and previously about both Germany and France. The core of this argument has to do with the circulation of knowledge. The modern history of knowledge is, in this reading, distinctly different from its counterpart history of science. The latter would typically talk about where, how, and why new knowledge emerges, especially based in the sciences. The former would rather focus on where, how, and why knowledge spreads and how this diffusion and uptake of new knowledge and ideas affect societies on a larger scale. Without this wider circulation of knowledge, Sweden’s “environmental turn” would not have been conceivable, nor would similar developments have been possible in other countries without similar diffusions of game-changing concepts and ideas.Footnote 45

How could this be possible in Sweden? Fundamentally, because knowledge had been a principal priority. Not only was it identified as a central element in securing a smooth and efficient transition to democracy in the interwar period, but knowledge was also part of Sweden’s postwar neutrality politics. It required a strong defense to deter large adversaries from devoting significant resources in considering an attack on Sweden. In turn, this demanded superb science and technology to maintain military capabilities. Swedish research and industrial policies were highly militarized and prioritized at the top political levels.

A complicating factor was that knowledge was not neutral. Isolated facts perhaps were, but the broader conclusions for policy certainly were not; nor were the narratives and metaphors that most people live by.Footnote 46 Media controversies stimulated environmental knowledge, especially in a country where newspaper readership was very high. Biochemist and socialist Hans Palmstierna’s attack against scientists that worked for industry sparked intense debate and was one of the controversies that politicized the environment in the early 1970s. Another controversy concerned the future, or rather futures studies. How should such studies be carried out? What about prognostications to adapt the economy and society for global competition? Should they be normative, aimed at finding pathways to lasting peace and a healthy planet? Topics like these touched on broad and powerful interests and provoked responses grounded in ideological convictions. In this way, the realm of “the environment” spread even further and could not be bounded by the areas of expertise of ecologists or chemists. It spread into all imaginable parts of society and impacted ever more interests and social groups, not just those living downstream or downwind from point sources of pollution. A result of these significant societal changes was the emergence of the so-called “alternative movement” – alternativrörelsen – for which the environment was a primary common denominator.

On the other end of the spectrum, established interests also mobilized. In his 1972 book Futurum exaktum, physicist Tor Ragnar Gerholm critiqued what he perceived as obscurantist “cultural pessimism” in the growing flora of environmental books and pamphlets. Some media, not least the business press, talked about “doomsday prophecies.” Others riposted, like the engineer and novelist Sven Fagerberg, who saw Gerholm’s book as “a lightly masked partisan contribution, intended to support the established industrial interests.”Footnote 47 Seen from the retrospective vantage point of today, the positions and fault lines of the debates may seem awkwardly simple. However, it is essential to see them, on the contrary, as working elements in an ongoing process of historical change. They were shaped in a creative phase of intense debate over ideas and political theory in the years around 1970 when “the environment,” a distinct topic since the late 1940s, made a quantum leap to become something it had never been before: an issue of societal change. This has remained ever since and has only been reinforced with the rise of the climate issue.

In these breakthrough years, millions of Swedes were part of a massive shift in consciousness as environmental issues in their widest sense were used to shed new light on the world they lived in, including their own country. This is also the way we can understand why knowledge became so important. What knowledge was, and how it was defined and by whom, became controversial. Physicists such as Gerholm and (the meteorologist) Bert Bolin stood on either side of a deep, wide trench. They shared insight into the laws of physics, but it meant totally different things to them. Defining and defending the “right” knowledge became essential.

Having come this far, we can summarize some of the factors that explain the solid, although far from spectacular, progress of Swedish domestic environmental politics. The first prerequisite, just like in many other countries, was the environmental turn itself, and we have identified the central importance of high-quality and widely available knowledge for this turn to take place and gain some hegemony in society. Strong leadership or smart tactical moves would have had no influence had this not been the case. Through the wide circulation of knowledge, Sweden had already passed a mental “tipping point,” to apply Malcolm Gladwell’s concept.Footnote 48 The public had learned just as well, if not better, than the economists that the environment and climate were important enough to protect by raising taxes. Underneath this lay yet another layer of insight, gained in the long-term building of the welfare state and folkhem: a relatively high confidence in taxes above international average levels. To these underlying factors should be added some general conditions for success, established over many years of research to identify the causes of effective environmental policies. Successful countries such as the Nordics, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands are characterized by strong public institutions. Like Sweden, they tend to have functional research policies and robust institutions for education and knowledge dissemination: high enrollment levels in higher education, active popular movements, civic engagement, transparent and independent mass media, and, not least, strong public service media.Footnote 49

In addition, there is a need for bold, committed politicians who are themselves knowledgeable enough to realize the importance of long-term environmental politics that deliver few short-term gains: politicians who can build political trust by linking the unavoidably technocratic articulation of what is good for nature to issues that citizens would care about. Environment and climate are, to begin with, gender and equity issues. The SUV, red meat, and big game hunting are predominantly masculine domains, and the Nordics seem to be no exception.Footnote 50 Women all over the world are disproportionately vulnerable to water scarcity and poisonous particles in households. Where girls and women are educated, their autonomy and influence grow, and the environment improves. The take home message seems to be that, first, an environmental turn must take place in a society, but to bring it to fulfillment, environmental policies that converge with broader sustainability concerns are required.

Tacit Properties – Arts, Culture, Gender

The widening social space of “the environment” and the gradual expansion of what might be called relevant expertise was an ongoing process and one that has continued into our own time. The process is as visible on the international stage as it is in a single country. Perhaps even more, with the rise of Earth system science, a genuinely interdisciplinary area of expertise that has influenced environmental governance, especially after the turn of the millennium. Expertise has also expanded into the social sciences, humanities, religion, and arts, as causes of environmental challenges are ultimately social and human and hence solutions must be too.Footnote 51 How has Sweden responded? In fact, as historical work on the era of the environment is now increasing, it is becoming more and more evident that the arts and the Geisteswissenschaften have played bigger roles than was previously assumed.

Perhaps tellingly, the earliest conscious effort to talk about the environment in modern terms in Sweden was arguably two books written not by a male scientist but by a female author, Elin Wägner, in the early 1940s (Figure 2.2). Wägner was a feminist, pacifist, regionalist, novelist, and journalist, and the second woman to take a seat in the Swedish Academy (from 1944). She was also an avid educationist, co-founding the Fogelstad Folk High School for Women in the 1920s, and a passionate gardener who argued for more ecologically friendly agriculture. With her Fogelstad feminist colleague, the large landowner Elisabeth Tamm, she co-authored the agrarian pamphlet Peace with the Earth (Fred med Jorden, 1940). From that work, she moved on to write a novel, Alarm Clock (Väckarklocka, 1941), in which she combined a critique of the “male” world war with an even more radical critique of the misconstrued economy and norms of modern, militaristic society. A central theme in both books were issues that would be called “environmental”: resource waste, pollution, food security, erosion, and decaying soils.

Figure 2.2 Elin Wägner, early feminist with ecological ideas. Her anti-war pamphlet Väckarklocka [Alarm Clock] (1941) is generally considered Sweden’s first articulation of a program for a responsible lifestyle that cared for the qualities of unspoiled nature and home-grown food.

These ideas kept reverberating long after her death in 1949. In the 1940s and 1950s, some of the most pronounced environmental critique concerned the harnessing of rivers with large hydropower dams, an issue also addressed by poets and novelists. In 1970, a dramatic conflict raged over the Vindelälven River. The most beloved of Swedish poets and singer-songwriters, Evert Taube, then in his eighties, composed a song called “Land of Angels,” coining that concept (änglamarken) and another, “Earth of Heavens” (himlajorden). Vindälven was one of only four of Sweden’s major rivers that were, ultimately, not harnessed for hydropower, unlike the dozens that were.

Issues of the environment and peace continued to mobilize artists, authors, and public intellectuals. Although it was scientists, doctors, and engineers who were typically asked to serve as experts, the wider public was probably more susceptible to being moved by artistic contributions. Environmental film became almost a sub-genre in its own right in the 1960s and 1970s. An emblematic example is The Apple War (Äppelkriget, 1971), set in a scenic apple-growing corner of southeast Sweden. In the film, the German capitalist Jean Volkswagner arrives in the cozy Swedish countryside setting with his PR man, and the two start dreaming of Deutschneyland, a theme park connected by mighty freeways to attract tourists. Local resistance and magic (!) manage to halt the plans, fully in line with the radical green politics of the two directors, Hans Alfredson and Tage Danielsson, leading figures of the Swedish intellectual humor stage in the second half of the twentieth century.

Environment-oriented journalism also reached a wide audience. Barbro Soller wrote in the Dagens Nyheter in the middle of the 1960s about fish and eggs contaminated by mercury. She was known in particular through a retrospective DN series entitled “Dirt-Sweden thirty years later” (“Lort-Sverige 30 år efteråt,” 1968–69) in collaboration with photographer Stig A. Nilsson. It departed from a highly controversial and extremely influential series of radio shows in 1938 on housing and hygienic conditions in the Swedish provinces. The series was based on a long car journey across the nation produced by author and social visionary Ludvig Nordström, an early proponent of hardcore medical and engineering solutions who was in almost any conceivable way the opposite of his contemporary Elin Wägner. Nordström also turned the radio show transcripts into a bestselling book.Footnote 52 Three decades later, Soller’s finding was that while homes and hygiene had improved enormously, a new large-scale and more complex set of problems had appeared in “the environment” that were more or less unknown to Nordström (e.g., mercury, dioxins, DDT, acid rain, soil erosion, overfishing, and overgrazing). Moreover, Soller noted that the concept of “the environment” had itself emerged in the intervening decades. She functioned initially as a mediator for engaged scientists, but increasingly came to serve as a more independent environmental voice toward the public – a new role in media at that time.Footnote 53

Another significant public intellectual on environmental issues was the historian Birgitta Odén at Lund University. Starting out as a quite traditional historian – an expert of Early Modern public finances – in the 1960s and 1970s, she transformed her professional and public profile to take on the role of a visionary entrepreneur and key driver in launching environmental history as a sub-field of the discipline in Sweden and the Nordic countries. She established contacts with funding agencies, served as an expert and government advisor, and engaged in planning, using the high level of trust she enjoyed to spread humanities-based environmental expertise across wide social and political circles. She also had close relations with her younger siblings, both of whom were scientists. Her sister Angelica von Hofsten was a botanist, and her brother Svante was a chemist who became famous for establishing acid rain as a scientific and political issue in 1967. Birgitta and Svante Odén were both together in a meeting with the Defence Research Institute and its General Director Martin Fehrm in the fall of 1967, a crucial moment during the environmental turn in Sweden. It was also an unlikely place to be for a historian at the time, but it was revealing for how expertise was assembled in new ways in response to a changing environment and political climate.Footnote 54

Wägner, Tamm, Taube, Alfredson, Danielsson, Soller, and Odén are in some ways representative of the type of expertise usually referenced in the mediated history of the environment: intellectuals (all of them) and scholars (Odén, indirectly Soller as well as Wägner). However, to an even greater extent, the large majority of these early leading environmentalists were also artists. They used words, music, and images creatively and convincingly. Hence, they reached out. They became known to multiple, in some cases enormous, audiences for whom they translated the insights gained by scientists working and publishing in styles and contexts where ordinary citizens had less access and could not be moved in the way that they were moved by Soller’s reporting, or by a movie like The Apple War.

This speaks to the very concept of environmental expertise. It cannot exclude an artistic and communicative dimension, more so than in other fields, because of the almost endless complexity of the environment, in the way that it is seamlessly interwoven with society, culture, and human behavior. The arts and humanities do the kind of work that explains how environmental knowledge can penetrate society and popular culture and become alive in mass media, popular movements, and politics, as well as in language and concepts. It is when knowledge and ideas enter societal institutions infused with agency that they gain the defining power that can in fact influence environmental futures. In these social processes, the voice of the philosopher or folk singer is just as important as that of the ecologist, the historian’s narrative is as directional as the chemist’s formula, and the conceptual analysis by the linguist is just as effective as the atmospheric calculations by the meteorologist. And above all, they have all needed each other in order to instigate societal change.

The reason that we elaborate upon the artistic and aesthetic presence of the environment in Swedish public life is that we see it as an important feature of the history we wish to tell in what follows of this book. It leads on to a central analytical question: whether these factors were of any real significance in explaining the success and contribution of Stockholm and Sweden in the rise of global environmental governance? We think they were, especially if we combine them with other tacit dimensions of the green transformation. One such aspect is gender. In science, women were always a minority, and still are. The famous Wenner Gren Foundation-funded meeting in Princeton, New Jersey, in 1955, “Man’s Role in Changing the Face of the Earth,” was attended by seventy-two men and one (1) woman, a biologist from India.Footnote 55 In the arts and humanities, it was always much different. Among the, admittedly, randomly composed group of seven Swedes above, four are women. It seems obvious that gender diversity and the presence of multiple forms of art and expertise have been essential for reaching out to a wider public in Sweden. Does the same hold true globally?

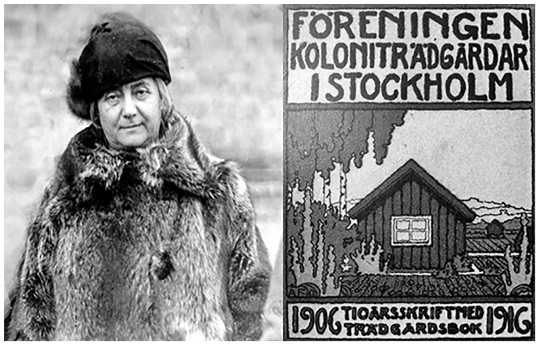

While our scoping of Stockholm-centric environmental networks suggests that a majority of the individuals comprising the “human environment” were men, a number of influential women have also been closely connected to the Stockholm story of environmental progress. As the most well-known recent environmental activist in the world, Greta Thunberg is an obvious example.Footnote 56 Also, one of the earliest “environmental activists” was from Stockholm, Anna Lindhagen, who pioneered the protection of public Stockholm parks and advocated their use for allotment gardens to allow low-income families to grow their own vegetables and get a small recreational space of their own (Figure 2.3).Footnote 57

Figure 2.3 Anna Lindhagen in a winter fur coat, c. 1920. Lindhagen was born into a family of lawyers, scientists, and politicians engaged in the urban politics of Stockholm. Alongside her regular position as a social worker and as an elected member of the Stockholm city council, she took on issues of urban beautification, social justice, and reform. She was a founder of the movement for allotment gardens in Stockholm in 1906. The booklet was published on the movement’s tenth anniversary in 1916. Anna Lindhagen in fur coat and the cover of an allotment garden advocacy brochure 1916.

Other women who made early and significant contributions include Alva Myrdal, scholar, cabinet minister, diplomat, and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, who advocated disarmament and led the process toward the establishment of the Swedish Institute for Futures Studies with a report published in 1972.Footnote 58 Inga Thorsson, a diplomat and stateswoman, initiated discussions that led to the Stockholm Conference. Former Social Democratic environment minister Birgitta Dahl held a central role in policy formation for decades.Footnote 59 So did the author, journalist, and liberal politician Kerstin Anér – like all those mentioned earlier, a staunch advocate of disarmament – and Birgitta Hambraeus of the Center Party, who was strongly engaged with energy and environmental issues during her long career in politics. The arguably most internationally well-known Swedish woman politician in the twenty-first century, Anna Lindh, was minister of the environment in the 1990s before becoming minister of foreign affairs, a post she held when she was assassinated in a department store in central Stockholm in September 2002.

In many fields, there was a broadening of female leadership, for example, in diplomacy, typically a male bastion. Former environment ambassador Viveka Bohn helped establish and champion the environment in the foreign office, which had little tradition of science and other areas of relevant expertise. The hydrologist Malin Falkenmark has been a leading figure in water and sustainability issues for over fifty years and was a key advisor during preparations for the Stockholm Conference. In the humanities, historian Birgitta Odén used her prestige and networks in science and academia to promote environmental history. Environmental journalism was pioneered in the 1960s and 1970s by Ami Lönnroth in Svenska Dagbladet and Åsa Moberg in Aftonbladet.Footnote 60 Crown Princess Victoria, following in the footsteps of her father, King Carl Gustaf XVI – an outspoken nature lover and avid hunter – has promoted sustainability issues internationally and drawn attention to the climate crisis during her extensive travels in the Arctic.

Women’s rights and family policies (e.g., generous parental leave) were politically already more established in Sweden than possibly anywhere else in the world in the 1970s and 1980s. At that time, the Swedish – and indeed Scandinavian – position as an environmental leader remained still largely unquestioned, as was the country’s reputation as a cauldron of official feminism. Both environmentalism and feminism were disproportionately represented as ideologies in the academic community, and environmental issues enjoyed strong scholarly links and networks. The greening of the curriculum provided women with new entry points into the sciences, where women had been relatively scarce before. Amplifying forces worked both ways. The relatively prominent position of women in politics and public life in Sweden turned out to be an asset for the environment. It is well known that women tend to be more pro-environment and that their presence influences decisions and institutions in this regard.Footnote 61 When looking for possible explanations for the early and strong environmental interest in Sweden, the role of feminism is an important factor, along with that of popular movements. Since its founding in the early-1980s, the Green Party has had many characteristics of a popular movement, and it also adopted the principle of dual spokespersons, one female and one male, which underscored the perception that green was also feminist.

Influence through Matter – The Spatial Dimension

There was an array of hard and soft underlying factors that contributed to Stockholm’s ability to play an outsized role in the development of foundational elements and architectures of international environment and sustainability science, politics, processes, and institutions. One was Sweden’s conception of itself as a föregångsland – a progressive pioneering country. This view was shared by many outside observers of the Swedish societal model; the image of Sweden as a forerunner in environmental policy.Footnote 62 Delegations arrived, from the Fabian Society in the United Kingdom to journalists, planners, and architects.Footnote 63 Social, scientific, political, and cultural characteristics played influential roles in supporting this image. Sweden’s geopolitical position as a nonaligned state, neutral in war (until 2009), and with a strong commitment to the United Nations and international development, was crucial for how the country navigated the international system. It also meant that other countries could be confident that Sweden had few obvious national interests at stake that created complications for various initiatives. Signing on to something led by Sweden was relatively low risk.

Sweden, and not least Stockholm, had a strong association with scientific excellence. This was due in the first place to remarkable scientific performance, especially from the 1940s, when most of the leading nations in Europe were hampered by the war and then reconstruction, and up to the 1980s, when Cold War research and development investments – including very large defense budgets – supported Sweden’s strong position in science and technology. Sweden’s image as a country of cutting-edge science has also been greatly enhanced by the glittering global brand of the Nobel Prizes, awarded by the Nobel Foundation and the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences since 1901. Every year on December 10, Alfred Nobel’s birthday, the world’s attention is fixed upon the Swedish capital for the award ceremony and Nobel Banquet. The prizes are a significant national asset that is exploited with increasing care by the Nobel Foundation, a mycelium of the establishment in Swedish society. Through their direct link to the Academy of Sciences, a promoter of environmental research since the early 1970s, the Nobel Prizes and the prestige they entail can also be seen as bestowing additional credibility upon Stockholm as a leading international center of environmental knowledge.Footnote 64

As home to, in certain periods, prominent members of the great generation of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century naturalists such as Linnaeus, Swedenborg, and Berzelius, the Swedish capital has in fact for centuries been a center of knowledge production in its own right. As we have already noted in Chapter 1 and will further elaborate in coming chapters, this role has only grown, and greater Stockholm, including the neighboring university town of Uppsala, is now among the most prolific science regions in Europe. A growing body of literature in recent years has suggested that knowledge has been a key to the growth and centrality of urban areas since the Renaissance, but especially in the period of science-based technologies and globalization.Footnote 65 Stockholm is a city of “knowledge clusters” and has benefited from the change away from spaces of assets to “spaces of flows” that dominate in the knowledge economy.Footnote 66 This literature has usefully pointed out the advantages cities enjoy in advancing knowledge and catalyzing activity, both nationally and internationally, and how the role of cities has changed in recent decades.Footnote 67 Increasingly, cities now take on roles in combating climate change, forming alliances of the willing to become greener and cleaner. In the United States, this trend has often been in stark opposition to the federal government’s inaction on climate since the signing of the Kyoto Protocol in 1997.

This literature also allows us to distinguish conditions particular to Stockholm and to make comparisons to other historical or contemporary centers of scientific and political initiative, such as London, Geneva, Berlin, and Copenhagen, the latter hosting the European Environmental Agency, or to places of concentrated specialized expertise, for example, Silicon Valley.Footnote 68 It has long been noted in the literature on the history of universities and the urban geography of knowledge that knowledge production and innovation tend to cluster, as do other sectors of society and branches of industry and commerce. The “Latin Quarter” phenomenon of cities dates back to the Middle Ages. Similar to how such areas tended to become established around cathedrals and colleges, today’s knowledge clusters congregate around science and industrial parks. What is perhaps less observed is how these urban concentrations can also serve as mental and social nodes of transformation. High densities of knowledge tend to foster progressive ideas and a spirit of embracing change. In this respect, it may be useful to note that Stockholm, for very particular reasons, has enjoyed a particularly high concentration of its intellectual and institutional resources for innovation in certain parts of the city.

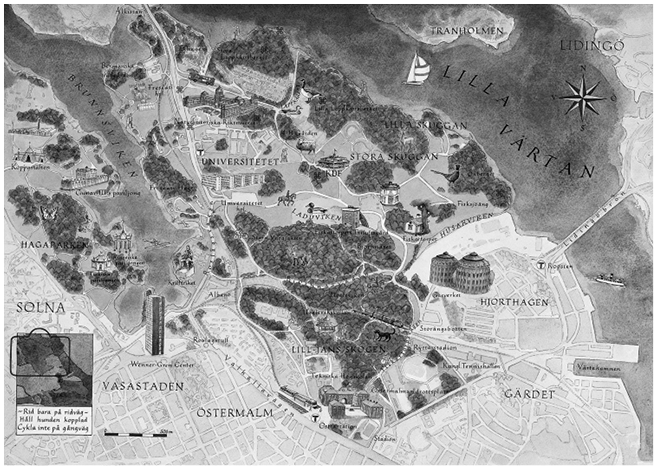

However essential, this was never planned. The modern growth in research and higher education in Sweden, like in most European countries, has been public, funded, and controlled largely by the state. When Stockholm began its ascent as a city of knowledge in the nineteenth century, earlier universities were in small provincial and ecclesiastic centers such as Uppsala and Lund, or on the outskirts of the Swedish Empire in Greifswald, Turku, Helsinki, and Tartu. It came naturally to locate universities on crown land. Such spaces were in abundance in Stockholm thanks to the existence of Djurgården (literally: the Animal Park), which had been royal hunting grounds since the Middle Ages. In this area in the northeastern sector of the city, public institutions have been continuously created: royal castles, large botanical gardens, and from circa 1800 military facilities. In the nineteenth century, hospitals and leisure activities expanded in this area, along with buildings for agricultural experimentation.

In the twentieth century, there was a literal explosion of buildings constructed for the KTH Royal Institute of Technology and Stockholm University. The building boom also included sports facilities such as the 1912 Olympic Stadium, a ski jumping facility and a skating rink, as well as several smaller colleges of arts and music, a veterinary college, a forest institute, the massive Museum of Natural History, the new Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences building from 1914, and Gustaf Arrhenius’ Nobel Institute for Physical Chemistry from 1910. Public agencies followed, such as the state-owned Swedish Radio and Swedish Television, concert halls, public archives, and the Sports and Gymnastics College. Later, in the early 1970s, a modernist “Film House” was built devoted to reel media, as were digital archives, a range of public research institutes, and, not least, large facilities and arenas for outdoor and indoor sports, including equestrian sports, slalom, tennis, and electric-lit trails for training and recreation. In the same green corridor, embassy compounds for the Nordic nations and other significant countries were also built (Figure 2.4).Footnote 69

Figure 2.4 Map showing parts of the Stockholm Urban National Park. These northwestern areas of the Swedish capital used to be royal land and as state property became home to the large majority of the scientific institutions of Stockholm that we discuss in this volume. Stylized map version for public spaces by Jan Wahlman for The Royal Palaces, Stockholm.

As home to the King and Royal Court, Stockholm was the capital of Sweden, and it turned out to be significant. But not for the King’s power. That formal authority had been gradually dismantled with the 1809 constitution and was further diminished with the establishment of full democracy and parliamentarism in 1921. In the early 1970s, all vestiges of Royal authority were completely removed with the so-called Torekov Compromise. In the small hamlet Torekov on Sweden’s west coast, representatives of the political parties in the ongoing inquiry into a new Swedish constitution agreed in August 1971 to let Sweden remain a kingdom on the condition that the King would only uphold ceremonial roles and never interfere with (party) politics. The proposal was presented in 1972.Footnote 70 These events belonged in the Zeitgeist of the Stockholm 1972 moment. These were times of upheaval. Symbolically, and emotionally, the final remnants of an ancien régime were laid to rest, which was fully congruent with the strong sense that something new was emerging and should be embraced. Even the Parliament and the Royal Court were part of the transformation. Winds of change were sweeping the land, and although the compromise was reached in an old countryside hotel, the shift itself took place in the capital. Sweden was Stockholm, and Stockholm was Sweden.

This massive concentration of public institutions and facilities in one city, in a very small dense fraction of the country’s vast territory, only increased during the course of the second half of the twentieth century. It also became Sweden’s largest assemblage of diverse and complex innovations, with most of the knowledge-related institutions and enterprises situated on royal property. Moreover, they were all literally located on the other side of the street – a wide Paris-style boulevard – from the largest urban center in the country, the downtown area of Stockholm. Named Vallhallavägen, in the Norse style common to this posh part of the city, it was laid out in the 1880s, with direct inspiration from Haussmann’s plan for Paris, as part of a massive deconstruction effort to remake Stockholm into a city of “air and light,” in the words of the rising literary star of the country, August Strindberg, who incidentally lived parts of his life in the French capital. The grand boulevard marked the – informal, as there was no problem crossing it – boundary to the existing city with its modern, reformed grid plan. On the city side, the streets were lined with everything a modern metropolis could encompass. This included, importantly, in the core areas near the royal castle, public agencies, political institutions and parties, large and small organizations, and representatives for literally all kinds of special groups and interests in Swedish society. There were also all kinds of media, from newspapers and book publishers to broadcast media and, from around 2000, social media, podcasters, and influencers.

The importance for Stockholm of this concentration of research and higher education, and the diverse urban fabric of the city, has not been formally estimated; it has rather been more assumed than assessed. However, the importance of such concentration for innovation has been analyzed for creative cities elsewhere in the world, and the implications of such research clearly shows that major cities and innovation go well together. Not least due to the fact that they serve as import havens for all kinds of new ideas and impulses.Footnote 71 This includes the new environmental ideas that emerged in the middle of the twentieth century. The concern over “nature” and “environment” was widespread across Sweden, and often abroad, from the Amazon to the Aral Sea, but the leading voices, pens, keyboards, and cameras in the country were in Stockholm, or at least had to travel to the capital to gain recognition for themselves and their causes.

A Smartness Game?

In the literature on the history of cities, it is often remarked that urban areas serve as gravitation points. Once one venture becomes established there, it provides an argument to situate another activity in the same place. Path dependencies are strong and typically accelerate with size. Together, they tend to build reasons for people to actively go there. Aristotle is often quoted: “It [the city] comes to be for the sake of life, and exists for the sake of the good life.”Footnote 72 Just as importantly, people gather in cities to make themselves seen and heard, to gain influence, and to argue their case, whatever that case might be. Cities are stages, increasingly used for mediation. In Sweden, as in for example France and the United Kingdom, but unlike in federal Germany and countries with strong regions such as Spain and Italy, the tendency was for activities of all kinds, not least media, to be disproportionately concentrated in the capital.

This is about understanding one of the more important aspects of international politics, societal mobilization, and scientific progress in the second half of the twentieth century and beyond. Over the course of this period, we argue, Stockholm has attained the status of not only a symbol but also a functional node of environmental science and governance, perhaps as the first among several other possible locations. Contenders would include New York, with the United Nations headquarters, and the San Francisco Bay Area, with its waves of unique contributions to preservation and conservation, and the planning of green spaces by Frederick Law Olmsted and the rise of a green counter culture.Footnote 73 Or Oslo, home to Arne Naess’ eco-philosophy and the city of the Nobel Peace Prize, is also recognized as the 2019 Green Capital of Europe for its green city planning.Footnote 74 These places, and similarly inspired cities around the world, belong within a wider urban movement to modernize sustainably and use their status as green cities to fast-track carbon-free futures, thereby building a new kind of competitiveness for the twenty-first century. In doing so, they articulate and build new generations of urban ecologies.

They are also, in that regard, competitors, and Stockholm is no exception. In a series of campaigns and statements, Stockholm has presented itself as the ultimate smart and creative city, especially in the context of northern Europe, but sometimes with global ambitions. Its efforts have not been completely farfetched. The growth of dotcom and IT companies and startups in gaming, music (Spotify), apps, and similar tech/entertainment economic sectors has led the city to think highly of itself, and it has also placed near the top of the global rankings of the “new economy.” The European Commission chose Stockholm as the Green Capital of Europe in 2010 when they first launched that award. In 2013, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) recognized Stockholm as a world-leading city when it comes to water quality, waste handling, and reducing carbon emissions. Stockholm was number one in ICT development and urban sustainability in 2014 and again in 2016, and ranked number four in The Monocle’s Quality of Life survey the following year.Footnote 75

Being “smart” does support the image of Stockholm as a forward-looking urban region, which dovetails nicely with its green urban persona. The city is obviously an important provider of infrastructure and services, and it is interested in supporting and expanding research and entrepreneurship. The city itself, however, has played a minor role in the story we tell. Although this urban version of a “socio-technical imaginary”Footnote 76 holds some sway and is clearly relevant, the green smart city is not the primary version of Stockholm that this book is about. It is also somewhat unclear what the relation of the city itself might be to global environmental governance. In many respects, it is rather the properties of Sweden as a nation, and as a progressive northern state, that have offered the qualities of “con.”

Stockholm has been the venue, the meeting place, and the carrier of the larger brand. Partly because it is the capital with the institutional density of government, agencies, institutions, academies, organizations, environmental and other NGOs, popular movements, foreign embassies, universities, research institutes, and think tanks, most within easy access of each other in a truly international atmosphere. To the outside world, “Sweden” has been “Stockholm.” In fact, official representatives of the city have been remarkably rare in meetings, reports, or even as meeting hosts, as the reader will become aware when the empirical detail of “environmental Stockholm” is being rolled out in the coming chapters. Stockholm has, on the contrary, been a grateful recipient of the power of the brand. The status of Stockholm on the global stage is not simply due to ABBA, Ingmar Bergman, a handful of hockey players, and a well-known welfare state: it is intimately connected to the emergence of what has become one of the largest and most consequential areas of international politics and governance.