The sounds of war: 1879 and after

This chapter explores ways of understanding the kinds of transformations and ‘migrations’ that occur when a language moves to a new medium, in this case radio.Footnote 1 I set out what particular tensions and plays of power operate when this occurs in an era when colonial, imperial, and, later, state power structures set languages in hierarchies of value. Through a close study of particular key moments in the history of the medium in South Africa, I discuss how radio in Zulu was able to adapt social knowledge and forms of performative power, creating a new ‘vernacular’ in a situation of unequal relations where silence and dancing to ‘his master’s voice’ might have seemed an easy option. And through the case of a particular key radio ‘migrant’, King Edward Masinga, I ask if ‘dancing to his master’s voice’ across languages and translations of culture can sometimes also be seen as a dance of power. What was in fact made through the new mediatisation of the black voice was a new set of publics within a wider public sphere, and new subjectivities (Kunreuther Reference Kunreuther2014).

One of the points made, often in the more obscure accounts of the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879–80 – obscure because the writers themselves were subaltern figures (for instance, Emery Reference Emery1879) – relates to the ‘noise’ made by the Zulu usually before battles. Often the accounts were in the diaries of young Welsh soldiers, their minds ‘edited’ well before they reached the battlefield to know that they were fighting the black pagan subjects of the British Empire.Footnote 2 Sometimes there is a mention of the sound of song coming across the darkness or the moonlit spaces that separated the two armies. These sounds are described as unsettling, strange, eerie, forlorn even. Such songs or chants, which were most likely the amahubo empi (war anthems), would have been used along with the izibongo (praise poems) of former kings as inspiration for the men about to go into battle against an imperial power whose leaders had forced war upon them. Thus, what was understood as ‘eerie and unsettling’ by one side was a source of deep inspiration and wisdom for the other. As Fisher remarks (of indigenous Australian radio voices), to ‘unsettle’ can also be a means of affirmation (Fisher Reference Fisher2016: 14). For its makers and performers in the battles of 1879 through to 1880, the songs and chants were a mark of how one was in the world. The oral texts, because one can think of a song or chanted poetry as a ‘text’ (Barber Reference Barber2007), travelled aurally and were an important part of anchoring the individual. But they were seen by imperial and colonial officials as part of the native exotic – and even, on occasions such as this, the threatening exotic. Certainly, the wisdom of the texts was seen as existing beyond and outside imperial discursive networks. Thus a binary was set up, and the premodern ‘other’ set in the imagination of the listener (Gautier Reference Gautier2014).

After the colonisation of Zululand and the breaking up of the Zulu kingdom in 1880, there was increasing migration to towns as men went in search of employment to pay the punitive taxes imposed by the imperial power. Nevertheless, the expressive forms that anchored people’s understandings of who they were, such as praise poetry, continued to operate. As a way of shaping and stating one’s identity they were vehicles for the construction of a social reality in which one had a place and an understanding of who one was. Praise poems, which were made for ordinary men and women as well as for Zulu royalty, constructed the personal and were composed by oneself and one’s age mates. At times, praise poems encapsulated the fleeting sight of a dramatically altering social reality. They were part of the process of identity-making within fluid and even conflicted social systems. For instance, the life of a foreign black soldier in World War One could be drawn in a few telling poetic utterances. The praise poems from the Hlabisa chiefly house in northern Zululand capture such moments: the praises hold in their brief but dense and allusive images the huge disparities in how the owner of the izibongo is treated at home and when he is a non-weapon-carrying combatant for the Allied Forces in the 1914–18 World War:

At approximately the same time, when Native Commissioners were established in districts of Zululand to dispense authority and the new power of the South African state, the strong awareness of these indigenous texts that validated social reality was turned by some Native Affairs officials into carefully documented accounts of the sonic and expressive world in which they found themselves. This was a social and political domain of sound that coexisted with the forms of paper bureaucracy that Native Commissioners had to administer and which their Zulu subjects had to negotiate and make part of a new vernacular. E. W. Grant was one such Native Commissioner who recorded on an early phonograph machine two elderly Zulu praise poets and published his account with the texts and historical background in the journal Bantu Studies. Calling his article simply ‘The izibongo of the Zulu chiefs’ (Grant Reference Grant1929), Grant put on record the links between poetic form and rhetoric and political authority and so gave a glimpse of the social value placed on the utterances and their place as one of the many ‘travelling texts’ that populated the bleak and far-flung hills of the district in northern Zululand over which he presided. Clearly, Grant battled with how best to understand this; he may even have hoped to gain kudos among his peers from his ‘native knowledge’. He published the poetry and the accounts of the elderly poets in a journal that was itself ambiguous in its attempts to engage with, comprehend, and publicise African social forms together with language, art, poetry, and narrative, all of which dealt with a different symbolic order. The journal, published by the University of the Witwatersrand from 1921, established a niche for some speculative and path-breaking studies within a wider context in South Africa in which hierarchies of race and knowledge were beginning to become normative.

The Grant article, like others in the early issues of Bantu Studies, unsettled rather than confirmed the view of a solid imperial world of knowledge and racial superiority. It did so somewhat obliquely through the ways in which it pointed to the presence of the sonic as a medium of a social world and ethical values, of travelling sound as text and its operation as organiser of social knowledge and memory as well as a maker of the everyday. The power of the form – its stately poetic quality, its commentary on history and character – was present, and the echoes it contained of the epic and minstrel traditions in Western verbal art were recognisable. It was thus presented by Grant as an item of arcane dignity but ambiguous in terms of value. Were the long stately poems collectors’ items reminiscent of a lost precolonial order? Or were they something else? Were they perhaps a gesture to an alternative knowledge structure and sound system? One that, in the days of late empire, knocked against bureaucratic missives of the Department of Native Affairs, yet for much of the time had its own existence where it was part of a technology of operational networks circulating along other lines?

The same ambiguity in understanding and placing items from the older sonic and social orders was present in the modernising African communities of the second half of the nineteenth century that were often attached to mission centres such as the American Zulu Mission at Inanda, close to the town of Durban (Hughes Reference Hughes2011). The izibongo and other forms of oratory, such as clan anthems (amahubo), dance chants (izingoma), and folk narratives (izinganekwane), to name but a few, were frequently discursive mediums and fluid genres that allowed a grappling with modernity but did not jettison understandings built over generations. What, in the latter decades of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, was often referred to as the kholwa community – the mission-educated African men and women, personified by men such as John Langalibalele Dube – also had to negotiate a way of taking on the value of older technologies of the sonic. John Dube, who was to become the first president of the ANC in 1912, was also deeply influenced by his interactions with African-American intellectuals such as Booker T. Washington. Partly through his pride in the African race imbibed during his stay in North America from figures such as the Washington-based African-American intellectual and distinguished journalist John Edward Bruce (Hughes Reference Hughes2011: 72–3), Dube was able to confront the increasingly sharp racism of white Natal settler leaders on his return home. He could also fold into this race pride a place for the discursive forms I refer to above, which were often bundled together as ‘folklore’, a term that in official parlance safely distanced them from the modern. Such forms in the cultural archive depended in the first instance on orality and can be understood as social networks of sound and a social construct of technology. Dube thus endorsed, even if with some ambivalence, the value of the forms of sound while working towards the founding of a modern nation (ibid.: 261). Sound texts, one could say, were both within and without the normative understanding of ‘the modern’ in Dube’s practice. As a social commodity of uncertain but definite value, they were perhaps something of a wild card. They can perhaps also be seen as migrant texts, travelling texts, capable of re-emplacement, adaptations, and new vernacularisations.

A new medium: radio, a new migrant

Radio and its soundwaves, in the South African context, found their way quite slowly into this unsettled world of the early decades of the twentieth century. In the new medium of radio, the travelling texts of orality were to find a place but the journey was not a simple or an easy one. The routes by which radio found its niche in South Africa were linked to the circuits of empire. In its early manifestations in South Africa and its broadcasts from makeshift technical rooms, first of all in Cape Town and Durban in the 1920s, with the first Durban broadcast coming from the City Hall in June 1924, radio sent out shards of political knowledge and popular culture from the British heart of empire to English-speaking settlers and to migrants from Europe for whom South African English became the new lingua franca (Rosenthal Reference Rosenthal1974).

Afrikaans, which was beginning to shape itself as an evolving modern language tied to the new ‘volk’, was largely silent on these early airwaves, as were the African languages of the region. For a brief period in the mid-1920s an African variety programme featuring the ‘Zulu Versatile Company’ had a slot in the Durban radio airtime, and Eric Rosenthal notes that it was also popular with many English-speaking listeners (Reference Rosenthal1974: 97). However, the first programmes aimed ‘officially’ at Zulu-speaking listeners did not come on the air until December 1941. As I mention in the Introduction, they seem only to have happened at all because of the ruptures of war and possible anxieties about a restive ‘native’ population at a time of crisis. Yet, in the way the narrative has been handed down, almost as an urban folk legend itself, it was the initiative of a single individual performing his way into the portals of the SABC Durban studios in Aliwal Street that began the Zulu airwaves sound. King Edward Masinga, a young headteacher who trained at Dube’s Ohlange Institute and obtained his teacher’s qualification from Adams College in around 1924,Footnote 3 desperate for the war news to be broadcast to Zulu listeners in their own language, walked into the Durban SABC studios and asked to be employed for this purpose as the first Zulu announcer. He met with a refusal, but instead of walking out sadly – or angrily – he performed his exit within a particular genre. Drawing on a set of gestures and an array of semiotics recognised as part of the powerful native exotic, he walked out backwards from the presence of the man who had said ‘No!’ (as one would when leaving the presence of Zulu royalty). As he did so, he exclaimed, as one would for Zulu royalty, ‘Bayede Wena weNdlovu! [Hail, You of the Royal House!; literally, ‘of the Elephant’] Bayede!’ At which point – so the narrative goes – the official figure of authority (undoubtedly the journalist and ethnomusicologist Hugh TraceyFootnote 4), changed his mind, and a deal was struck.Footnote 5

With this version of how isiZulu found a spot on the airwaves, the trope of the ambiguous, potentially powerful outsider, balanced by that of the trickster figure, came into play. Each remained operative ways of articulating, directing, and imagining African-language radio – or ‘Radio Bantu’ as it became officially known in 1960. Like a character in an epic or folk narrative, Masinga found an entry for himself and his ‘people’ into the magical but dangerous kingdom of radio through flattery, and by performatively recalling a set of gestures that were already quite anachronistic but were nevertheless still full of symbolic valence and affect, and linked to memories of old power and modern nationalism (La Hausse de Lalouvière Reference La Hausse de Lalouvière2000). Each trope – that of the powerful outsider and that of the trickster figure – can be seen as variously illuminating different aspects of how ‘the native’ took to the air in ways not entirely dictated by the ‘master’. The breaching of the portals of the Durban SABC marked, in a way, the moment when the texts of orality migrated into the new aural medium and signalled the beginning of what we could call a new Zulu social order of the air. To put it another way, it was a kind of migration. It marked the beginning of a new ideology of voice, of voice as a different kind of expressive agency. It was perhaps unsettling to some as well as deeply satisfying to others. Kunreuther notes in relation to the entry of FM radio into Nepali life in the 1990s that, through voice, Nepalis came to understand themselves as ‘voicing subjects within the limits and possibilities of a host of emerging publics’ (Reference Kunreuther2014: 9). Masinga’s entry was half a century earlier and into a deeply undemocratic moment. Yet it was to create changes of a similar magnitude.

Masinga: the trickster and maker

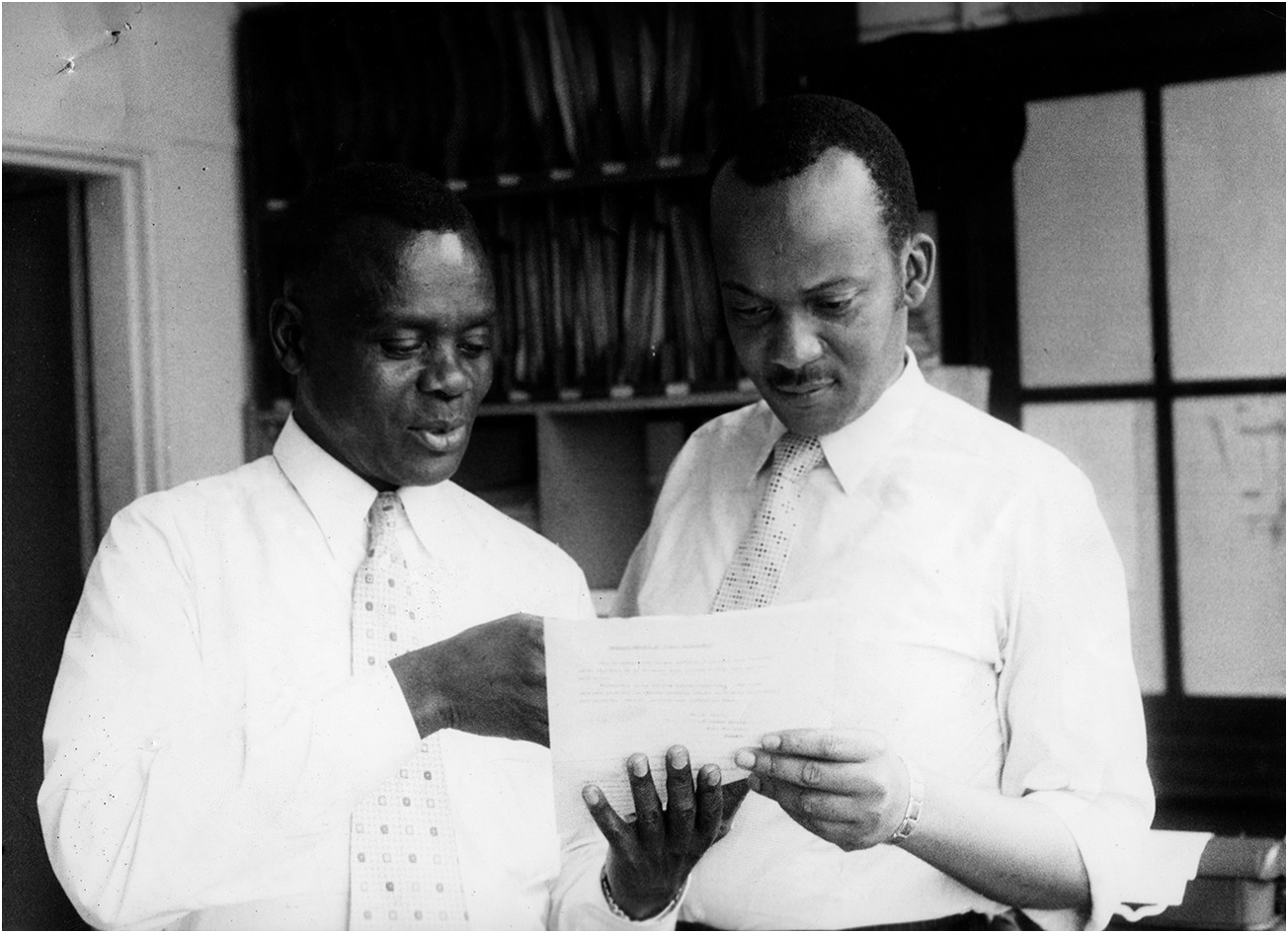

The personality who dominated the new venture was K. E. Masinga himself. His first broadcast in December 1941 was a three-minute news clip on the progress of the war. These short news items in isiZulu became a regular feature of the service from Durban and gradually increased in length to five minutes, with other items such as ‘sketches, dramas of folklore in Zulu, then dramas on crime does not pay and health programmes’ all added by Masinga himself, although he must have been aided by Hubert Sishi, who joined the Durban SABC to work with Masinga in 1945.Footnote 6 Masinga clearly had ambitions for a Zulu radio service that extended far beyond such items of information, no matter how important these were in the context of South Africa’s fortunes in the uncertain arena of World War Two. The question, for our interest in the migrations of culture and the setting up of African-language radio, is how he tried to create a public media space for isiZulu in a new global medium. Moreover, as the Zulu language on radio, it was also to become an increasingly important national medium of communication and identity formation when the odds seemed stacked against him. How did Masinga manage it? His first real move in carving out a space for texts that were in one sense ‘folk’ yet were also embedded in the new medium occurred in about 1943 (the precise date cannot be confirmed), when, with Hugh Tracey, he produced the musical script of a folk tale, Chief above and Chief below, with ‘original songs by the author in traditional idiom’ (Tracey and Masinga: Reference Tracey and Masinga1945; Coplan Reference Coplan1985: 160; Gunner Reference Gunner2000a: 234; see Mhlambi Reference Mhlambi2008; Reference Mhlambi2015). The recasting of an oral story in the new medium was hugely popular, particularly with migrant hostel dwellers in Durban who listened not through wireless sets but by means of rediffusion, which transmitted the broadcast items via cable to a central distribution point. This, then, must have constituted a kind of public–private listening space where groups of hostel dwellers would listen together, respond to the radio items, and discuss them both individually and collectively. Masinga, eager for ‘a fully blown Zulu broadcasting service for the black community’,Footnote 7 did not impose his ideas on listeners, but rather, with his soon-acquired colleagues Guybon Mpanza and Hubert Sishi, sought the views of those at whom the broadcasts were aimed. This meant moving around in workers’ hostels and in factories, gathering listeners’ views and needs (Couzens Reference Couzens1985), and turning their finds back into use in the snippets of Zulu-language airtime allowed them.

Figure 1.1 The King! The broadcaster King Edward Masinga broadcasts on Durban SABC’s Bantu programme, c.1956.

Figure 1.2 K. E. Masinga, senior announcer of the SABC’s Zulu programme, with his colleague, Hubert Sishi, discuss the programme for the November 1957 African Arts Festival in Durban, October 1957. They were chairman and secretary of the festival.

The migration of the established oral form to a new sound where voice became mediatised was clearly intrinsic to Masinga’s vision for a classical modern Zulu culture that was part of modern technology and, because of its oral base, was particularly well suited to radio. What Masinga may not have always emphasised as he carried out his balancing acts with his austere and undoubtedly powerful SABC ‘masters’ was that popular culture and popular music – both Zulu forms such as early maskanda, which he would sing himself with banjo accompaniment, and singers such as Frank Sinatra – were part of the new programmes. These helped create a sense of popular culture and the modernising black world – a world in which, at times, the urban and the rural fed off and into each other.

In the course of his long career as a multiskilled broadcaster working with the Zulu language, Masinga seems to have performed many careful balancing acts. As he found throughout the whole of his career, which ended formally in 1971 but went on informally much longer, this was imperative when constantly working with powerful superiors in a racial hierarchy of radio where voice was always black but the controllers, both technical and in terms of authority, were always white.Footnote 8 This quite chilling and seemingly unbreachable hierarchy of race can be seen, for instance, in the congratulatory reports and pictures in the SABC Bulletin of 5 February 1962, which reports on the birth of the ‘Commercial service of Radio Bantu’. Two pictures show black announcers in front of a microphone. In one, Bhekisisa Kunene (later well known in radio drama), is at the desk for the ‘first day-long Zulu Service’. The other photograph features two announcers, Petros Tumane and Thabo Chaka, who were ‘responsible for the first South-Sotho broadcasts from Johannesburg’. Yet the real power appears to lie within the three pictures of white officials in suits and ties, in two cases holding cups of tea and chatting to each other, and in the third ‘watching the first broadcast’.Footnote 9 The question remains: did they know they were ‘sewing dragons’ teeth’? Clearly not.

Masinga’s guile and determination to pass through forms of control to create the free space of imagination that a musical such as Chief above and Chief below and other subsequent items brought to the airwaves were impressive in their own right. Yet they seem even more impressive when set alongside the crude official attempts to use the airwaves, with language regarded as a simple and singular sledge-hammer medium for information and communication alone, to be directed at a subject population. In this vein, the earliest archived recording of isiZulu featuring alongside English, Afrikaans, Sesotho, and isiXhosa is in the Johannesburg Sound Archives of the SABC in Auckland Park, dated September 1942.Footnote 10 The strange and strained register of the announcements, which are introduced and concluded by ‘African’ sounds (a clip of men’s voices in antiphonal song with rhythmic handclaps, a flute melody, a lion’s roar), was perhaps an attempt at African-sounding rhetoric, but a white voice of authority delivers a wartime message about the extension of radio broadcasts to ‘the Abantu [people] of our land’. Extracts from the English announcement (which followed that in Afrikaans) are as follows:

There will be broadcasts for Natives from today. Hear this word which makes known in the land that by the kind-heartedness of our country’s wireless system a boon is being granted to the Natives of our land, namely the Abantu of the Union of South Africa … We begin this morning with an explanatory statement by the Department of Native Affairs … Because of the generosity of the SABC from today 30 minutes on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday will be broadcast at 9.30 in the morning by the SABC for the Abantu.Footnote 11

It must have been clear to the astute black listener that only some kind of perceived national crisis had occasioned this largesse. Harcourt Collett, the announcer for the English segment, with his high-pitched, strangulated BBC-like voice, so similar in its speech register and authoritative tone to other African British colonial radio services (Bloom Reference Bloom, Bloom, Miescher and Manuh2014), continued to inform ‘the Natives’:

Yes indeed there are still loudspeakers in the big cities in our country. They will go on, set there by the Native Affairs Department [NAD], but the different programmes on the air will start today. There will be nothing on holidays or on Sundays or only if considered to be necessary for the country as a whole as an emergency.Footnote 12

In a sense, this was shutting (or perhaps opening) the stable door after the horse had bolted. Masinga and his new colleagues were already busy with war news and other items for Zulu listeners of the SABC, working from the Durban studios, and the elaborate Masinga–Tracey radio recasting of the story Chief above and Chief below would soon be on the air. As I point out in the Introduction, the deeper unease about controlling a subject people in a time of crisis was indeed behind not only the September 1942 announcement but also the December 1941 Masinga breakthrough. It appears that Hugh Tracey, picking up on an early example of ‘radio trottoir’ (Ellis Reference Ellis1989), had persuaded his superiors at the Durban SABC that airtime in isiZulu was essential as a means of ensuring that the rumours in the black community of an imminent Nazi victory, which began to surface in South Africa during the Russian campaign, were quashed (Coplan Reference Coplan1985; Couzens Reference Couzens1985).Footnote 13

Wireless sets as commodity, sound as commodity

Although, in the early 1940s, rediffusion was most common among black listeners and amawayilense (wirelesses) were unknown outside the small African elite, all this was soon to change. The writer and journalist Herbert Dhlomo reported in the Zulu-language weekly Ilanga lase Natal in 1948 that ‘thousands of Africans have receiving sets’ (Couzens Reference Couzens1985: 237). The heavy items of furniture that constituted wireless sets in those days would probably not have been found in many black homes. It was sound itself rather than the sets that was the important commodity. The sound, which I argue had in some way migrated to radio texts, was itself a heady commodity comprising not only transformed oral narratives, histories of the Zulu past as drama (in this both Masinga and Sishi excelled; see Sishi Reference Sishi and Ntuli2000), and varieties of song and poetry, but entirely new sound objects too. Masinga and his early radio colleagues were migrants and adventurers rather than antiquarians.

There was also the issue of translation, and cultural translation. There is virtually no archival trace (as far as I am aware) of the nine Shakespeare plays that Masinga translated and that were put out in the Zulu programme airtime, probably over the English service of the SABC. The Shakespeare plays seem to have been on the air in the early 1950s, as Masinga was elected to the International Mark Twain Society in 1953 and in the same year his translations of King Lear and The Tempest were serialised on the SABC (Coplan Reference Coplan1985: 161). Masinga himself refers to his translations and renderings of The Merchant of Venice, Romeo and Juliet, A Comedy of Errors, and Macbeth in his interview on the English Service in the 1950s.Footnote 14 Yet all that remains is a spoken four-minute extract, in English and isiZulu, of Mark Anthony’s famous ‘Friends, Romans, countrymen’ funeral oration from Julius Caesar. Masinga recited the isiZulu with great dramatic vigour – ‘Zihlobo, bakwethu, maRomani …’ [Friends, Romans, countrymen …] – the actor Ian Calder recited the English far more calmly. The snippet was archived in both the English and Zulu service and aired – perhaps on both programmes – on 18 March 1955.Footnote 15 Was this, too, an instance of a kind of cultural translation, where the political weight of something approaching Zulu praise poetry could be felt in the revolutionary speech of a Roman politician, itself a ‘translation’, of a kind, by a sixteenth-century English dramatist?

Figure 1.3 ‘Enjoy both with an Eveready Spacegram’, Ilanga newspaper advertisement, January 1960.

Figure 1.4 ‘Yonga imali!: Something to save for, something to treasure’, advertisement from Natal Radio and Furnishers, Durban, in Ilanga newspaper, January 1960.

If we can think of sound, in the particular instance of radio, at a particular time, and within a certain frame, as a commodity, we can perhaps also understand it as a contested commodity. Saul Dubow has noted how the ideas of racial segregation that marked the Smuts (United Party) years of government in South Africa (which ended with the 1948 election) were characterised by ‘ambiguity and ideological flexibility’. This differed markedly, Dubow argues, from the National Party ideology of apartheid with its ‘unremitting zeal and logic’ (Reference Dubow1989: 178). Yet both Deborah Posel and Dubow have argued that there was no ‘grand plan’ of apartheid. That widely held idea is a myth. Posel suggests that a close look at the workings of the state reveals a series of struggles, with revisions and adaptations. There were uncertainties, conflicts, factions, and deviations. She notes that, in the early 1950s, the threat of African mass resistance was still present, with serious gaps exposed ‘in the state’s control over the urban proletariat’ (Posel Reference Posel1991: 5, 6; Dubow Reference Dubow2014: 293). Radio played a role in this.

Expansion, control, and ‘straight lines’

The problem is that the moment we give the Native a radio and encourage him to listen, we place in his hands a weapon which may harm the Native himself.Footnote 16

By the time the Hon. Minister Herzog made this remark in parliament in June 1959, the truth on the ground – as opposition members of parliament repeatedly pointed out – was that many thousands of African listeners already had licences for radios. ‘Natives’ were using the English and Afrikaans services of the SABC and Springbok Radio, the commercial station available, and many were also listening to the Zulu and other African-language programmes available in the time allotted. In addition, there was a vibrant and very popular rediffusion service that was being used in Orlando and Jabavu townships on the West Rand, where lines went straight to people’s homes. It was run by the Orlando Rediffusion Service Ltd with the agreement of the SABCFootnote 17 and provided listeners with a wide range of programmes, including some from outside the SABC. There was popular pressure for the service to be expanded to neighbouring townships and the Orlando Rediffusion Service was keen to oblige.

The appetite for radio and the commodity of sound was huge. A company called Titan Enterprises and Exploration, based in Boksburg on the East Rand, was keen to sell radios ‘in Bantu Areas’ and in early 1960 applied to the NAD for permission to do this. The response to this request was astonishing. Not only was there a refusal, but a letter was sent to Chief Bantu Affairs Commissioners in Bloemfontein, Pietersburg, Pietermaritzburg, Potchefstroom, Umtata, and King William’s Town informing them of the situation. In other words, as if a severe epidemic was about to hit the land, the controllers of ‘Native Affairs’ in far-flung corners of the country – the centre, north, south, and east – were prepared, warned, and informed of the decision that this was not to be allowed. Radio sets were not to be sold to ‘the Bantu’ who lived in areas – urban or rural – that were designated as being under the control of Native Commissioners. Titan Enterprises was informed, politely, of the decision and no reason was given.

The smooth and unctuous words of the minister in parliament in 1959, quoted at the start of this section, contained an assumption of the truth of rigid racial hierarchies and the ease of control. Yet the statement hid, perhaps not very well, a profound sense of panic about radio. The National Party government had laid out spatial control of segregation through post-1948 legislation as far as it could, but radio seemed to need control of the atmosphere, the air itself. How was this to be done? Radio, moreover, was a medium that defied even spatial boundaries through the freedom of imagination, conversation, ideas, and knowledge which it enabled, something that I write about in more detail in Chapter 5. The National Party plan was to obtain an amendment of the 1936 Broadcasting Act (inspired by Lord Reith of the BBC) and to institute a Bantu Programme Control Board (BPCB) that would be separate from the rest of the SABC. This would control programmes for the ‘Bantu’. In this way, the National Party, and principally the new prime minister, Dr Verwoerd, hoped to control the sound and voice, and everything else, that went over the air to the ‘Bantu’. New transmitters were to be built that would allow FM transistor radios to be used – transmitters that would send out signals at very high frequency so that the reception was excellent. These signals would reach listeners in even the remote rural areas. The new FM transistor radios would receive the radio waves that came in ‘straight lines’ (a phrase the minister used about the new system) but would not pick up other radio signals. It was a wonderful and devious plan to control the airwaves. The powerful transmitters were put in place in 1962, and in some ways they were very effective. In others, though, the plan was as futile as it was vicious. It could work in rural areas and give excellent reception for a limited range, but in urban areas it was absolutely unworkable because of the proliferation of signals that listeners could pick up.

The amendment to the Broadcasting Act was passed in the face of intense and passionate – and also very well informed – opposition in parliament. The attempt to control the commodity of sound, and to optimise already far-reaching levels of surveillance, went into national operation. In June 1960 a new radio station named Radio Bantu came into being which would broadcast in Zulu and in some of the other main African languages, in the first instance Sesotho and isiXhosa. Radio was to become indeed a ‘weapon’, but one to be used by the government.

Again, the metaphor of the bolting horse and the stable door closed too late comes to mind. Was all the above, the elaborate plan with its longing for ‘straight lines’ rather than crooked airwaves, too late, as the powerful radio stations of independent Africa – Ghana, Radio Cairo, and others – beamed their signals across borders? Was it also too late as, by this time, the Zulu service that had begun in the early 1940s (with other African-language services – South Sotho, isiXhosa, SiNdebele, Xitsonga, and Setswana – coming later) had established its own voice and body of informed listeners? These services were already working with new radio genres, translating at a number of levels, mixing and remixing cultural forms for a new community of the air. Was it a case of too much too late?

The answer has to be yes and no. Surveillance, long in operation, continued and was intensified as the positions of white controllers became more formalised and the Board for Radio Bantu was set in place. Programmes were monitored, and so were the black staff. And yet, in some ways, perhaps it was too late. A migration had taken place. New voices of cultural authority were on the air. The ambiguous domain of ‘folk’ art had been remade and remixed alongside new forms, and the trickster figure of King Edward Masinga, ‘migrant’ and maker, had survived. Surveillance had stalked him, too. In 1957, when the United States government invited him to be a participant in the Foreign Leaders Programme of the International Educational Exchange Service, he was given a passport but only after police clearance. Moreover, he had to put down a deposit of a considerable sum of money that was only returned once he was home and had handed back his passport, when he became once more merely a ‘Bantu’ subject and not, officially, a South African citizen.

While in America he lectured at a number of universities: ‘Hertford University, Howard, Boston, and some universities also in Washington and Indiana,’ he explained to his English-service SABC interviewer on his return in January 1958.Footnote 18 Masinga, never one to favour modesty, explained in reply to the carefully phrased, and loaded, question, ‘Did you have time to travel?’:

I think I got all I wanted … I had all the travel facilities laid on for me. I travelled from coast to coast of the United States. Most of those journeys … were to TV studios, broadcasting and mostly universities. I had no time for sound broadcasting. I was rather interested in television itself … at first all those lights were really a little bit dazzling but I soon got used to them.Footnote 19

Masinga informed his interviewer that he had lectured on African folk songs and music and on African social anthropology ‘that was of high interest in America’, and that he also conducted research in the southern states: ‘Alabama, Virginia, Arizona [sic] where the Negro lives in the rural areas’. He complained about accent and obliquely touched on deeper questions of race, identity, and belonging in America:

One handicap was that the Negroes have got a certain growling and nasalising dialect … a drawl which I do not understand readily … [and] the Northern Americans I am afraid find it very difficult also to understand one another.Footnote 20

Although not able to control his travel in North America, the South African government, as mentioned above, made sure that Masinga returned his passport when back in the country. But with the visit Masinga became yet another of the many South Africans – including John Dube – who in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries had made the transatlantic journey and shared knowledge of social and cultural forms across the gaps of history and the attempts at domination. Unlike his contemporaries, Bloke Modisane and Lewis Nkosi, neither of whom was allowed a passport, he seemed to be able to move beyond the closed borders of the country with a kind of untouchable bravado. Again, it was perhaps a dance, a tricky performance, but inspired and courageous. Modisane and Nkosi, whose own radio lives were made outside the country and who are the subjects of Chapters 3 and 4 respectively, were faced with different challenges connected with race, power, and culture. These they handled with their own combinations of ingenuity and panache. For each of them, too, as for Masinga, voice performed many functions in which agency was a central feature.

Language, power and ‘the King’

On 31 May 1961, South Africa became a republic and thus threw off the last formal vestiges of the British Empire. Radio Bantu and the African-language services, including Radio Zulu, continued. Masinga stayed in place, subordinate but in some ways always ‘kingly’. To the end, he saw the space between languages and cultures as one for negotiation, power, and play. When, in 1970, he was awarded a ‘prize’ by the ‘Nguni Services’, he masterfully turned the tables on his white ‘masters’ as he ‘thanked’ them for his prize. He did so by using the poetic language of izibongo to name each of his superiors, and he thus captured them in the image of the ‘other’, seemingly subaltern, language. In his acceptance speech, given almost 30 years after his first bold entrance through the portals of the SABC in Durban, he moved between English and isiZulu. As he switched between languages, a colleague translated for him – but he was the master. The harshest praise name of all was kept for a Mr Louw, a senior official of the station. Mr Louw’s praise name of Umthakathi (Dangerous Wizard) is left untranslated in the English, and Masinga’s comment in isiZulu is harsh and yet opaque and gives little ground:

Ngiyakubonga Mthakathi. Sonke siphikisana ukuvumelana. [I thank you Mthakathi. We all have intense disagreements but in the end we manage to get along.]